Key Points

Question

Are there differences in ischemic and bleeding outcomes among East Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention associated with administration of low-dose prasugrel (loading dose, 20 mg; maintenance dose, 3.75 mg) vs clopidogrel (standard dose)?

Findings

This cohort study of data from 2770 East Asian patients provided from a contemporary multicenter registry in Japan showed that the proportion of ischemic events associated with low-dose prasugrel administration were comparable to those of clopidogrel; however, the use of prasugrel, even at this lower dose, was associated with a higher incidence of bleeding events compared with clopidogrel use.

Meaning

These findings suggest the importance of preprocedural bleeding risk assessment prior to selecting P2Y12 inhibitors, even at lower approved doses, to prevent avoidable bleeding complications.

Abstract

Importance

Prasugrel was approved at a lower dose in 2014 in Japan than in the West because East Asian patients are considered more susceptible to bleeding than Western patients. However, real-world outcomes with low-dose prasugrel treatment remain unclear.

Objective

To investigate the association of low-dose prasugrel vs standard-dose clopidogrel administration with short-term outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study used data from the Japan Cardiovascular Database–Keio Interhospital Cardiovascular Studies registry, a large, ongoing, multicenter, retrospective cohort of consecutive patients who underwent PCI. The present cohort study evaluated 2770 patients with acute coronary syndrome who underwent PCI and received either low-dose prasugrel (loading dose, 20 mg; maintenance dose, 3.75 mg) or clopidogrel (loading dose, 300 mg; maintenance dose, 75 mg) in combination with aspirin between 2014 and 2018. Propensity score–matching analysis was conducted to balance the baseline characteristics of patients receiving low-dose prasugrel and those receiving clopidogrel. Data analysis was conducted in June 2019.

Exposures

Prescription of either low-dose prasugrel or standard-dose clopidogrel prior to PCI.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary ischemic events (in-hospital death, recurrent myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke) and primary bleeding events, defined as bleeding complications within 72 hours after PCI consistent with the National Cardiovascular Data Registry CathPCI Registry definition.

Results

Of 2559 patients included in the study, the mean (SD) age was 67.8 (12.7) years, and 78.2% were male. In total, 1297 patients (50.7%) received low-dose prasugrel, and 1262 patients (49.3%) received clopidogrel. After propensity score matching, primary ischemic events among patients receiving low-dose prasugrel and those receiving clopidogrel were comparable (odds ratio [OR], 1.42; 95% CI, 0.90-2.23), but primary bleeding events were significantly higher among patients receiving prasugrel (OR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.63-5.18). This increase in bleeding events was associated with the presence of a profile of high-bleeding risk (≥75 years of age, body weight <60 kg, or history of stroke or transient ischemic attack) (OR, 4.08; 95% CI, 1.86-8.97), being female (OR, 3.84; 95% CI, 1.05-14.0), or the presence of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.05-4.09) or chronic kidney disease (OR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.95-11.7).

Conclusions and Relevance

Since its approval, low-dose prasugrel has been used by nearly 80% of patients who undergo PCI. Despite the modified dose, bleeding events were higher among patients receiving low-dose prasugrel than among patients receiving clopidogrel, with no difference in ischemic events between the 2 groups. These results suggest the importance of a risk assessment of bleeding prior to selecting a P2Y12 inhibitor, even for the use of a lower approved dose, when treating patients of East Asian descent.

This cohort study assesses the association of low-dose prasugrel vs standard-dose clopidogrel administration with ischemic events and bleeding outcomes among East Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is the cornerstone for the treatment of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1 Administration of standard-dose prasugrel (loading dose, 60 mg; maintenance dose, 10 mg) was associated with a lower incidence of ischemic events but a higher incidence of bleeding events compared with clopidogrel in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial.2,3 Accordingly, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have provided class 1B recommendations for prasugrel administration when treating patients with ACS undergoing PCI and also have recommended dose adjustments for patients with a high risk of bleeding (≥75 years of age, body weight <60 kg, or a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack).4,5,6,7

East Asian individuals have a higher risk of bleeding events than Western individuals.8,9,10 Thus, there is the hypothesis that dose reduction in antiplatelet therapy may be more suitable for the East Asian population when considering the risks and benefits provided by such medications.8 Accordingly, the efficacy of low-dose prasugrel (loading dose, 20 mg; maintenance dose, 3.75 mg) was compared with that of clopidogrel in a pivotal randomized clinical trial called the PRASFIT-ACS trial in Japan.11 In that trial, low-dose prasugrel was associated with a lower incidence of ischemic events and similar incidence of bleeding events compared with clopidogrel in a select patient population (eg, relatively young patients with few comorbidities). Since its approval in 2014, low-dose prasugrel has rapidly become a valid treatment choice. However, the frequency of real-world use (eg, among relatively older patients with comorbidities) and the incidence of ischemic and bleeding events associated with low-dose prasugrel administration remain unclear.

The present study assessed the prescription patterns and patient demographic characteristics of low-dose prasugrel use and compared the in-hospital ischemic and bleeding outcomes associated with low-dose prasugrel administration with that of clopidogrel administration among patients with ACS undergoing PCI.

Methods

Study Design

The Japan Cardiovascular Database–Keio Interhospital Cardiovascular Studies (JCD-KiCS) is a large, ongoing, multicenter, registry-based, retrospective cohort of clinical data collected from consecutive patients undergoing PCI in 4 major teaching hospitals in Tokyo Kanto.9 The baseline characteristics between this registry and the national PCI registry (J-PCI) have been previously reported to be similar, ensuring the generalizability of the JCD-KiCS registry across Japan.12 The clinical variables in the JCD-KiCS were defined according to the ACC-sponsored National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) CathPCI Registry to enable comparative research between the United States and Japan and to investigate disparities in the management of PCIs.9 Details regarding variable definitions are provided in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement. The present study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.13 The ethics review committee of each participating hospital reviewed and approved the protocol for this study, and all participants provided written informed consent. No one received compensation or was offered any incentive for participating in this study.

To obtain a robust assessment of care and patient outcomes, baseline data and outcomes data were collected from medical records by clinical research coordinators who were trained by the primary investigator (S.K.) and the project coordinator. The data were entered into an electronic data-capturing software system, which has a robust data query engine and system validations for data quality. In addition, to ensure the accuracy of the adverse events, the JCD-KiCS was supported by an events committee that included board-certified cardiologists (M. Sawano, S.K.), and the committee adjudicated on major procedural complications (eg, death or bleeding events or cardiac and cerebrovascular events). Initially, all periprocedural adverse events were reviewed by a trained clinical research coordinator under the supervision of the project coordinator and categorized into complications in need of adjudication and complications clearly not associated with cardiovascular disease or the index procedures. One events committee member reviewed the abstracted record; a second or third adjudicator was called on in the event of disagreement between the project coordinator and the first adjudicator. For patients with extended hospital stays, we restricted the coding of the postprocedural events to 30 days after the last procedure, in accordance with the definition provided by the NCDR.9

Overall, 22 373 consecutive patients undergoing PCI between July 2008 and March 2018 were included in the study. For a fair comparison between low-dose prasugrel approved in 2014 and clopidogrel, PCI case records were extracted from the registry between January 2014 and March 2018. In total, 2770 patients with ACS who underwent PCI and who received either drug were included in this study (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). One patient with missing baseline demographic characteristics, 24 patients (0.9%) who underwent multiple PCIs during a single hospitalization, and 3 patients (0.1%) who underwent an acetylcholine provocation test for possible vasospastic angina were excluded. Forty-four patients (1.6%) who received no antiplatelet therapy, 129 patients (4.7%) who received single antiplatelet therapy, and 10 patients (0.4%) who received triple antiplatelet therapy were also excluded. The final study population comprised 2559 patients. Data analysis was conducted in June 2019.

Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Administered Prior to PCI

Patients received either low-dose prasugrel (loading dose, 20 mg; daily maintenance dose, 3.75 mg) or clopidogrel (loading dose, 300 mg; daily maintenance dose, 75 mg), in combination with aspirin, according to the current Japanese Circulation Society guidelines.14 Prasugrel and clopidogrel are readily available in Japanese hospitals, including in our participating facilities, and thus could be administered at the discretion of the treating cardiologist.

A loading dose of prasugrel or clopidogrel was administered at the time of diagnosis of ACS before the procedure for patients undergoing PCI with stenting. The PRASFIT-ACS trial did not exclude patients with the following risk factors identified to be high risk for bleeding in TRITON-TIMI 38 or in observational studies: 75 years of age or older, body weight lower than 60 kg, or history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.11 Moreover, there are no specific rules or restrictions set by local society guidelines or regulatory authorities for the selection of patients who will receive low-dose prasugrel administration. Administration of a standard dose of ticagrelor was approved by the Japanese pharmaceutical agency in 2016; however, the drug has not been widely prescribed by Japanese physicians largely because of concerns for increased risk of bleeding events observed after administration of ticagrelor to patients from East Asian countries.15

Primary Ischemic and Bleeding Events

Primary ischemic events comprised in-hospital death, recurrent myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke during hospitalization. The other end points included each component of major ischemic events (in-hospital death, recurrent myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke), post-PCI cardiogenic shock, and post-PCI heart failure during hospitalization.

Primary bleeding events were defined as bleeding complications within 72 hours after PCI documented in the medical record that were associated with any of the following: (1) requirement for transfusion of whole blood or packed red blood cells or (2) procedural intervention or surgery at the bleeding site to reverse or stop or correct the bleeding (such as surgical closures or exploration of the arteriotomy site, balloon angioplasty to seal an arterial tear, or endoscopy with cauterization of gastrointestinal bleeding). Blood transfusions unrelated to the PCI procedure were not recorded as primary bleeding events. The clinical research coordinators collected the outcomes data from both in-hospital and outpatient medical records a few months after hospital discharge, which guaranteed the least amount of missing outcomes data in cases of early hospital discharge within 72 hours. Furthermore, bleeding complications were divided into puncture-site bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, genitourinary bleeding, and other bleeding. These definitions were in accordance with those of the NCDR CathPCI Registry, version 4.1.9 The secondary end points comprised bleeding events equivalent to noncoronary artery bypass graft–related thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) major bleeding and TIMI minor bleeding. The TIMI major bleeding was categorized as intracranial or clinically significant bleeding with a decrease of 5 g/dL or more in the hemoglobin level (to convert hemoglobin level to grams per liter, multiply by 10.0). The TIMI minor bleeding was categorized as clinically overt bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin level between 3 and 5 g/dL.

Statistical Analysis

The demographic characteristics and in-hospital outcomes were compared between patients receiving low-dose prasugrel and those receiving clopidogrel. Normality of continuous variables was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test or Q-Q plot visual assessment or both, and continuous variables with normal distributions are expressed as mean (SD) values; other variables are expressed as median values (interquartile ranges). Statistical comparison of baseline characteristics and outcomes was performed using t tests or Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables and using Pearson χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate, for categorical variables. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

We then conducted a propensity score (PS)–matching analysis to assess the association of low-dose prasugrel and clopidogrel with ischemic and bleeding events in a matched cohort based on the PS calculated from all potentially unbalanced and clinically important covariates. The PS was calculated for each patient using a logistic regression model predicting the association of the selection with the low-dose prasugrel group as the loading agent prior to PCI from the variables that were considered important outcome risk factors and from the factors used for selecting low-dose prasugrel or clopidogrel. The variables included in the PS are provided in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement. Matching was performed with a 1:1 matching protocol without replacement, using a caliper width equal to 0.2 of the SD of the PS. We compared the baseline characteristics and outcomes using the PS-matched cohort. We estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs using logistic regression analysis.

Finally, prespecified subgroup analyses were performed. First, the entire cohort was stratified based on the clinically important factors provided in eAppendix 3 in the Supplement, and the PS was calculated in each category. Then, the PS-matched cohort was created in the same manner as the main analysis, and the same comparisons between the 2 groups were performed for each category. There were missing data for less than 1% of the patients for the baseline variables, except for body mass index (n = 84 [3.3%]). To account for missing data, a single mean imputation was used. All statistical analyses were performed in June 2019 with SPSS, version 23.0.0 (SPSS Inc) and R, version 3.1.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

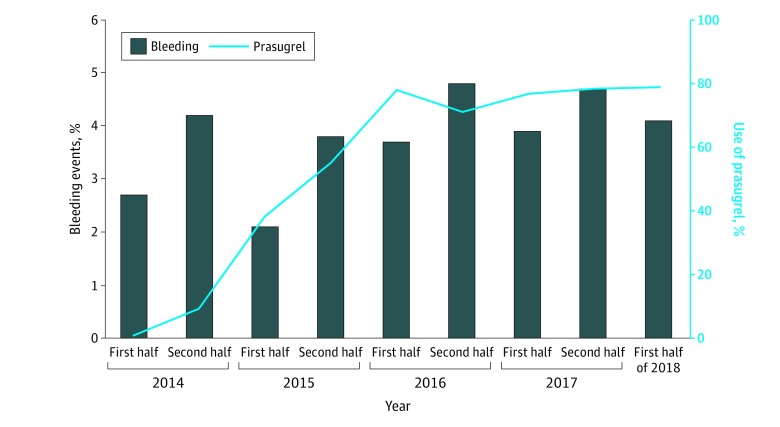

Of 2559 patients included in this study, the mean (SD) age was 67.8 (12.7) years, and 78.2% were male. In total, 1297 patients (50.7%) received low-dose prasugrel and 1262 patients (49.3%) received clopidogrel. Compared with patients who received clopidogrel, patients who received low-dose prasugrel were younger (mean [SD] age, 69.3 [12.4] years vs 66.4 [12.7] years), had a lower bleeding-risk profile, and included a higher proportion of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI; 491 [38.9%] vs 748 [57.7%]) and transradial intervention (901 [71.4%] vs 1098 [84.7%]) (Table 1). After the approval of low-dose prasugrel, the use of low-dose prasugrel in combination with aspirin increased rapidly from 5.2% to 78.9% between 2014 and 2018; the trend was similar across patients with profiles of low- vs high-bleeding risk (Figure 1 [line plot]; eFigure 2 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). The crude incidence of bleeding events increased gradually during the study period (Figure 1 [bar graph]).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With ACS Receiving Clopidogrel or Prasugrel, Before and After Propensity Score Matching.

| Characteristic | Before matching, No. (%) of patients | P value | Standardized difference | After matching, No. (%) of patients | P value | Standardized difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel (n = 1262) | Prasugrel (n = 1297) | Clopidogrel (n = 901) | Prasugrel (n = 901) | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 69.3 (12.4) | 66.4 (12.7) | <.001 | −0.23 | 68.0 (12.9) | 67.8 (12.6) | .76 | −0.02 |

| ≥75 | 468 (37.1) | 366 (28.2) | <.001 | 303 (33.6) | 296 (32.9) | .73 | ||

| Male | 951 (75.4) | 1049 (80.9) | .001 | 0.14 | 689 (76.5) | 697 (77.4) | .66 | 0.02 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 23.9 (3.9) | 24.1 (3.8) | .07 | 0.07 | 23.9 (4.1) | 23.9 (3.6) | .84 | 0.009 |

| Weight <60 kg | 549 (44.5) | 465 (36.3) | <.001 | 369 (42.0) | 355 (39.7) | .32 | ||

| Hypertension | 987 (78.2) | 882 (68.0) | <.001 | −0.22 | 658 (73.0) | 658 (73.0) | >.99 | 0.000 |

| Dyslipidemia | 836 (66.2) | 714 (55.1) | <.001 | −0.23 | 540 (59.9) | 545 (60.5) | .81 | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 375 (29.7) | 340 (26.2) | .05 | 0.08 | 241 (26.7) | 248 (27.5) | .71 | 0.02 |

| Smoker | 422 (33.4) | 489 (37.7) | .03 | 0.09 | 320 (35.5) | 315 (35.0) | .81 | −0.01 |

| COPD | 47 (3.7) | 28 (2.2) | .02 | −0.11 | 25 (2.8) | 24 (2.7) | .89 | −0.008 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 583 (46.2) | 472 (36.4) | <.001 | −0.20 | 369 (41.0) | 365 (40.5) | .85 | −0.009 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 154 (12.2) | 169 (13.0) | .55 | 0.025 | 116 (12.9) | 124 (13.8) | .58 | 0.03 |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD), g/dL | 13.2 (2.3) | 14.0 (2.1) | <.001 | 13.5 (2.3) | 13.8 (2.1) | .006 | ||

| <10 | 110 (8.7) | 55 (4.2) | <.001 | −0.22 | 61 (6.8) | 49 (5.4) | .24 | −0.07 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 119 (9.4) | 60 (4.6) | <.001 | −0.23 | 50 (5.5) | 56 (6.2) | .55 | 0.03 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 86 (6.8) | 40 (3.1) | <.001 | −0.22 | 40 (4.4) | 36 (4.0) | .64 | −0.03 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 215 (17.0) | 134 (10.3) | <.001 | −0.22 | 107 (11.9) | 125 (13.9) | .21 | 0.07 |

| Previous heart failure | 93 (7.4) | 30 (2.3) | <.001 | −0.34 | 26 (2.9) | 30 (3.3) | .59 | 0.03 |

| Previous PCI | 345 (27.3) | 194 (15.0) | <.001 | −0.35 | 162 (18.0) | 182 (20.2) | .23 | 0.06 |

| Previous CABG | 32 (2.5) | 17 (1.3) | .03 | −0.11 | 15 (1.7) | 16 (1.8) | .86 | 0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 124 (9.8) | 115 (8.9) | .42 | 0.03 | 75 (8.3) | 85 (9.4) | .41 | 0.04 |

| Cancer | 62 (4.9) | 56 (4.3) | .51 | −0.03 | 43 (4.8) | 40 (4.4) | .74 | −0.02 |

| Transradial intervention | 901 (71.4) | 1098 (84.7) | <.001 | 0.37 | 712 (79.0) | 724 (80.4) | .48 | 0.04 |

| STEMI (vs NSTE-ACS) | 491 (38.9) | 748 (57.7) | <.001 | 0.38 | 417 (46.3) | 417 (46.3) | >.99 | 0.000 |

| Out-of-hospital cardiac pulmonary arrest | 46 (3.6) | 79 (6.1) | .004 | 0.10 | 33 (3.7) | 42 (4.7) | .29 | 0.04 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 98 (7.8) | 110 (8.5) | .52 | 0.03 | 70 (7.8) | 81 (9.0) | .35 | 0.04 |

| VA-ECMO | 29 (2.3) | 19 (1.5) | .15 | −0.07 | 12 (1.3) | 16 (1.8) | .45 | 0.04 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pumps | 130 (10.3) | 144 (11.1) | .52 | 0.03 | 89 (9.9) | 92 (10.2) | .81 | 0.01 |

| Hemodialysis | 54 (4.3) | 28 (2.2) | .002 | −0.15 | 27 (3.0) | 25 (2.8) | .78 | −0.02 |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSTE-ACS, non–ST-segment elevation–acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

SI conversion factor: To convert hemoglobin to g/L, multiply by 10.0.

Figure 1. Time-Based Trends of Low-Dose Prasugrel Use and Crude Incidence of Bleeding Events in Japanese Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome.

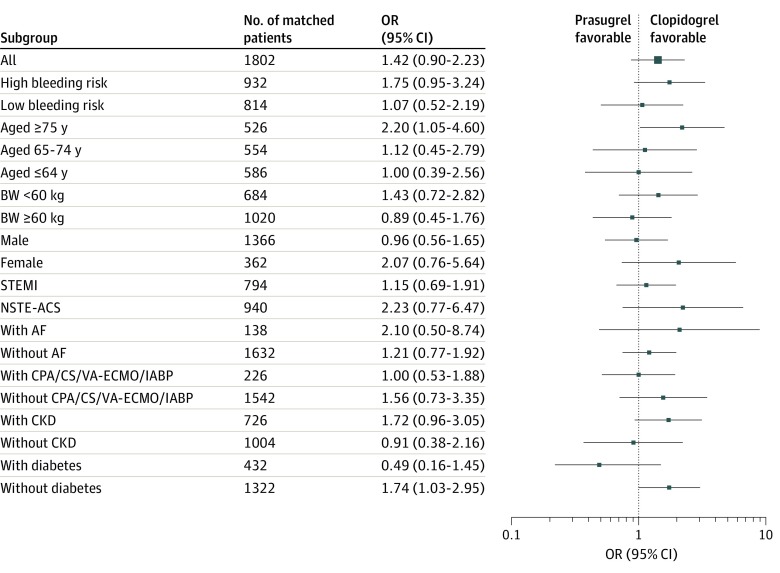

The distribution of the PS between patients receiving low-dose prasugrel and those receiving clopidogrel overlapped substantially between the 2 groups (eFigure 4 in the Supplement). The PS matching generated 901 pairs of patients. After PS matching, there were minimal differences between the 2 groups, with a standardized mean difference of less than 0.1 for all variables included in the matching process (Table 1; eFigure 5 in the Supplement). There was no significant difference in the proportion of primary ischemic events (46 patients [5.1%] vs 33 patients [3.7%]; P = .17) between patients receiving low-dose prasugrel and those receiving clopidogrel (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.90-2.23; P = .14), and a similar outcome was observed in all the subgroups (Table 2 and Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the incidence of each component of the primary ischemic events, the post-PCI cardiogenic shock, or the post-PCI heart failure between the 2 groups.

Table 2. Ischemic and Bleeding Outcomes of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome Associated With Receiving Clopidogrel or Prasugrel, Before and After Propensity Score Matching.

| Outcome | Before matching, No. (%) of events | P value | After matching, No. (%) of events | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel (n = 1262) | Prasugrel (n = 1297) | Clopidogrel (n = 901) | Prasugrel (n = 901) | |||

| Primary ischemic events | 57 (4.5) | 62 (4.8) | .78 | 33 (3.7) | 46 (5.1) | .17 |

| Death | ||||||

| In-hospital | 49 (3.9) | 50 (3.9) | >.99 | 28 (3.1) | 37 (4.1) | .31 |

| Cardiovascular | 45 (3.6) | 39 (3.0) | .44 | 26 (2.9) | 29 (3.2) | .78 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | .17 | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | >.99 |

| Ischemic stroke | 4 (0.3) | 12 (0.9) | .08 | 3 (0.3) | 9 (1.0) | .15 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 31 (2.5) | 30 (2.3) | .90 | 20 (2.2) | 19 (2.1) | >.99 |

| Post heart failure | 36 (2.9) | 33 (2.5) | .72 | 22 (2.4) | 22 (2.4) | >.99 |

| Primary bleeding events | 37 (2.9) | 57 (4.4) | .06 | 16 (1.8) | 45 (5.0) | <.001 |

| Transfusion related to PCI | 25 (2.0) | 38 (2.9) | .12 | 9 (1.0) | 30 (3.3) | <.001 |

| Procedural intervention/surgery | 2 (0.2) | 13 (1.0) | .007 | 2 (0.2) | 9 (1.0) | .07 |

| Bleeding | ||||||

| Puncture site | 12 (1.0) | 15 (1.2) | .70 | 2 (0.2) | 14 (1.6) | .004 |

| Gastrointestinal | 5 (0.4) | 8 (0.6) | .58 | 3 (0.3) | 7 (0.8) | .34 |

| Genitourinary | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | >.99 | 0 | 2 (0.2) | .50 |

| Other | 21 (1.7) | 30 (2.3) | .26 | 10 (1.1) | 21 (2.3) | .07 |

| TIMI major | 28 (2.2) | 45 (3.5) | .06 | 18 (2.0) | 32 (3.6) | .06 |

| Cerebral | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | .38 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | >.99 |

| TIMI minor | 93 (7.4) | 197 (15.2) | <.001 | 69 (7.7) | 132 (14.7) | <.001 |

| Other outcomes | ||||||

| Acute kidney injury | 189 (15.6) | 189 (14.8) | .58 | 119 (13.8) | 130 (14.7) | .59 |

| De novo dialysis | 18 (1.4) | 21 (1.6) | .75 | 10 (1.1) | 16 (1.8) | .32 |

| Coronary dissection | 5 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | .50 | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | .22 |

| Coronary perforation | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | .73 | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | .69 |

| CABG after PCI during hospitalization | 10 (0.8) | 10 (0.8) | >.99 | 6 (0.7) | 7 (0.8) | >.99 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Figure 2. Subgroup Analyses Representing the Odds Ratios (ORs) of Low-Dose Prasugrel Associated With Primary Ischemic Events.

Squares represent mean ORs; error bars, 95% CIs. High bleeding risk is defined as patients 75 years of age or older, body weight (BW) lower than 60 kg, or a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack; low bleeding risk is defined as younger than 75 years of age, BW 60 kg or more, and no history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CPA, cardiac pulmonary arrest; CS, cardiogenic shock; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; NSTE-ACS, non-ST–segment elevation–acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; and VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

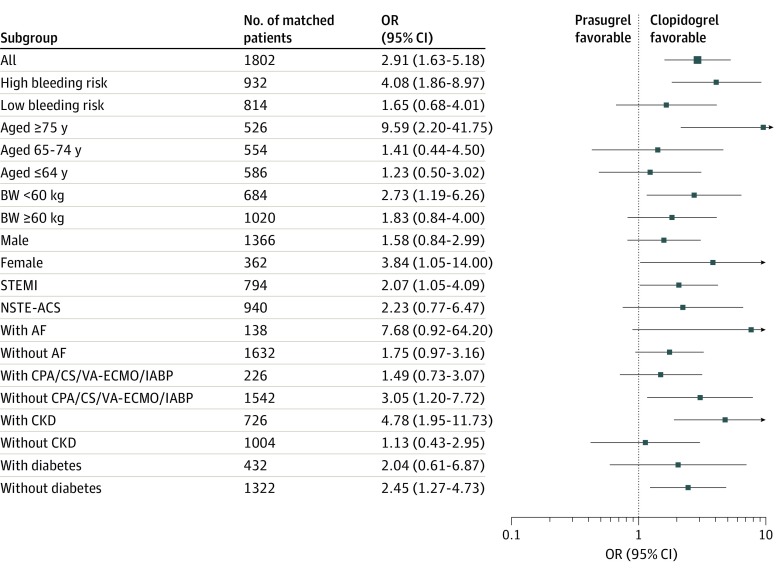

Primary bleeding events were significantly higher in the low-dose prasugrel group than in the clopidogrel group (45 patients [5.0%] vs 16 patients [1.8%]; OR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.63-5.18; P < .001) (Table 2). The incidence of TIMI minor bleeding was significantly higher in the low-dose prasugrel group (132 patients [14.7%] vs 69 patients [7.7%]; P < .001), whereas TIMI major bleeding showed a nonsignificant increase (32 patients [3.6%] vs 18 patients [2.0%]; P = .06). Moreover, the increased bleeding risk was associated with the presence of bleeding risk profiles defined as high by the ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines (OR, 4.08; 95% CI, 1.86-8.97; P < .001), female sex (OR, 3.84; 95% CI, 1.05-14.0), presence of STEMI (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.05-4.09), or chronic kidney disease (OR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.95-11.7) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Subgroup Analyses Representing the Odds Ratios (ORs) of Low-Dose Prasugrel Associated With Primary Bleeding Events.

Squares represent mean ORs; error bars, 95% CI. Definitions and abbreviations are described in the legend to Figure 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first and the largest real-world study to compare the short-term ischemic and bleeding outcomes between the administration of low-dose prasugrel and the administration of standard-dose clopidogrel, with a specific focus on East Asian patients with ACS, a population with a higher risk of bleeding than that of Western patients. The main findings of our study were as follows: (1) the incidence of ischemic events with the administration of low-dose prasugrel was comparable to that for administration of clopidogrel; however, (2) the use of prasugrel, even at a lower dose, was associated with a higher incidence of bleeding events compared with clopidogrel, and (3) this was predominantly observed among patients defined as having a profile consistent with a high risk of bleeding by the ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines, among women, and among patients with STEMI or chronic kidney disease. These findings suggest the importance of a preprocedural risk assessment of bleeding prior to selecting P2Y12 inhibitors to prevent avoidable bleeding complications among East Asian patients with ACS.

Dose adjustment of antithrombotic agents, particularly for East Asian patients, is an increasing concern because more than 20% of the global population resides in this region.8 Asian patients with atrial fibrillation have different characteristics and higher anticoagulant- or antiplatelet agent–associated bleeding complications than Western patients16; hence, a reduced dose of non–vitamin K oral anticoagulant has been approved for stroke prevention and is frequently prescribed in some East Asian countries.17,18 Similar explanations have been applied to the use of antiplatelet therapies for East Asian patients with ACS undergoing PCI; thus, low-dose prasugrel was tested and approved for use based on the PRASFIT-ACS trial in Japan.11 However, we found that a higher incidence of short-term bleeding complications was still associated with the administration of low-dose prasugrel compared with that for clopidogrel treatment. Moreover, the bleeding concerns were particularly evident in Korea, China, and Taiwan, where standard-dose prasugrel or ticagrelor is recommended in parallel with the ESC and the ACC/AHA recommendations.19,20 Considering the critical need for the development of appropriate antiplatelet treatment strategies for East Asian patients with ACS, our study contributes to a growing body of literature on dose adjustments of novel P2Y12 inhibitors.

Low-dose prasugrel has rapidly become the medication of choice for patients with ACS, and this practice pattern is consistent with the findings of a recent randomized clinical trial.21 This practice pattern is unique to Japan because, although the use of preprocedural clopidogrel has decreased with the launch of ticagrelor in the United States, it has not decreased to the same extent.22 Notably, our subgroup analyses revealed that the risk of primary bleeding events was associated with patients with profiles defined as being at high risk of bleeding.6 Furthermore, the use of prasugrel was not associated with a reduced risk of ischemic events among such patients. This suggests that a similar warning may be necessary for Japanese cardiologists to ensure the appropriate use of low-dose prasugrel and to avoid bleeding events in Japanese patients undergoing PCI.14 Risk stratification according to a patient’s bleeding-risk profile is warranted because a marked increase in prasugrel use was observed for this category in our study.

In Japan, most, if not all, P2Y12 inhibitors (low-dose prasugrel or clopidogrel) are administered at the time of diagnosis of ACS before confirmation of the coronary anatomy. This is largely because recent studies examining low-dose prasugrel use in Japan reported that the administration of prasugrel at the time of diagnosis of ACS was associated with significantly reduced in-stent thrombus or plaque protrusion immediately after PCI compared with the administration of prasugrel after coronary angiography prior to PCI, without any differences in the bleeding rates.23 In addition, an emergent or urgent coronary artery bypass graft is rarely performed for Japanese patients presenting with ACS owing to patient and institutional preferences against surgical procedures; therefore, patients have minimal exposure to the potential bleeding risks associated with bypass surgery.24 Neither the protocols of randomized clinical trials that have been approved in Japan nor the Japanese clinical practice guidelines have elaborated on the optimal timing for pretreatment with low-dose prasugrel (ie, at the time of diagnosis of ACS or immediately after diagnostic angiography) for patients with ACS undergoing PCI.11,14 Our study reported higher incidence of bleeding events associated with low-dose prasugrel use than with clopidogrel use. This may be associated with the inherent risks of prasugrel administration or it may be associated with the timing of the administration, considering the results of the ACCOAST (A Comparison of Prasugrel at PCI or Time of Diagnosis of Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction) trial (the ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines based on this trial recommend against administration of standard-dose prasugrel for patients in whom the coronary anatomy is unknown).7,25,26 Although the precise mechanism or reason cannot be identified in the present study, our findings raise questions regarding the present practice guidelines and whether prasugrel administration should be restricted to patients at lower risk of bleeding or whether prasugrel should not be used before angiography. Further assessments of the timing of prasugrel administration and its safety are warranted.

In our study, a similar incidence of primary ischemic events, even in every subgroup analysis, was observed for low-dose prasugrel and clopidogrel administration, and these results are consistent with those of the PRASFIT-ACS trial (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.56-1.07).11 From the viewpoint of ischemic events, these results are reassuring because there are concerns of increasing incidence of ischemic events associated with the use of low-dose P2Y12 inhibitors in a real-world setting. Our results may reflect the recent findings of the decrease in the incidence of ischemic events due to the development of novel devices for PCI, including second- or third-generation drug-eluting stents,27 and suggest that we should pay more attention to bleeding complications when selecting antiplatelet therapies.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we cannot disregard the possibility of unmeasured confounders that were not accounted for by PS matching. Second, our study assessed only in-hospital outcomes; thus, there is a possibility that long-term benefits could be observed with the use of low-dose prasugrel. Additional studies must be conducted to assess the long-term outcomes and appropriate duration and regimen of dual antiplatelet therapy after hospital discharge.28,29 However, considering the magnitude of the association of in-hospital bleeding events with long-term major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events,30,31 we believe that our results contribute to a growing body of literature on appropriate antiplatelet therapies. Third, we could not identify the number of patients that switched P2Y12 inhibitors during hospitalization; a switch from clopidogrel to prasugrel is unlikely, whereas the reverse may occur because clopidogrel is available as a generic medication, and the patient’s financial burden should be considered. Fourth, we had no data on the proportion of patients who received loading doses of antiplatelet therapy that may have affected short-term outcomes.

Conclusions

The use of low-dose prasugrel has increased since its introduction in Japan, and the drug is currently administered to as many as 80% of patients with ACS. The ischemic events associated with the administration of low-dose prasugrel were comparable to those of clopidogrel, but the use of low-dose prasugrel was associated with a higher risk of short-term bleeding events. These short-term bleeding events were mainly associated with the presence of a profile defined by the ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines as being high risk of bleeding, female sex, and the presence of STEMI or chronic kidney disease. Our study suggests the importance of tailoring antiplatelet regimens in the modern era to patient characteristics.

eAppendix 1. Details Regarding Variable Definitions

eAppendix 2. Variables Included in the Propensity Score

eAppendix 3. Factors Regarding Pre-Specified Subgroup Analyses

eFigure 1. Study Flowchart

eFigure 2. Time Trend of Low-Dose Prasugrel Use and Crude Incidence of Bleeding Events in High Bleeding Risk Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome

eFigure 3. Time Trend of Low-dose Prasugrel Use and Crude Incidence of Bleeding Events in Low Bleeding Risk Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome

eFigure 4. Histogram of Propensity Score Distribution for Prasugrel and Clopidogrel

eFigure 5. Standardized Mean Differences Before and After Propensity Score Matching

References

- 1.Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(5):-. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. ; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators . Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001-2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiviott SD, Desai N, Murphy SA, et al. Efficacy and safety of intensive antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel from TRITON-TIMI 38 in a core clinical cohort defined by worldwide regulatory agencies. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(7):905-911. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. ; 2012 Writing Committee Members; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2012;126(7):875-910. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318256f1e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. ; CF/AHA Task Force . 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(4):529-555. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267-315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine GN, Jeong YH, Goto S, et al. Expert consensus document: World Heart Federation expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in East Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(10):597-606. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohsaka S, Miyata H, Ueda I, et al. ; JCD-KiCS and NCDR . An international comparison of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a collaborative study of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) and Japan Cardiovascular Database-Keio interhospital Cardiovascular Studies (JCD-KiCS). Am Heart J. 2015;170(6):1077-1085. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong YH. “East Asian paradox”: challenge for the current antiplatelet strategy of “one-guideline-fits-all races” in acute coronary syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(5):485. doi: 10.1007/s11886-014-0485-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito S, Isshiki T, Kimura T, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjusted-dose prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in Japanese patients with acute coronary syndrome: the PRASFIT-ACS study. Circ J. 2014;78(7):1684-1692. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Miyata H, et al. Performance and validation of the U.S. NCDR acute kidney injury prediction model in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(14):1715-1722. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura K. Kimura T, Ishihara M, et al; Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group. JCS 2018 Guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Circ J. 2019;83(5):1085-1196. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goto S, Huang C-H, Park S-J, Emanuelsson H, Kimura T. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese patients with acute coronary syndrome—randomized, double-blind, phase III PHILO study. Circ J. 2015;79(11):2452-2460. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lip GYH, Wang KL, Chiang CE. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for stroke prevention in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: time for a reappraisal. Int J Cardiol. 2015;180:246-254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan YH, Kuo CT, Yeh YH, et al. Thromboembolic, bleeding, and mortality risks of rivaroxaban and dabigatran in Asians with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(13):1389-1401. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cha MJ, Choi EK, Han KD, et al. Effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2017;48(11):3040-3048. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park K-H, Jeong MH, Kim HK, et al. ; KAMIR-NIH Registry Investigators. Comparison of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in Korean patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing successful revascularization. J Cardiol. 2018;71(1):36-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serebruany VL, Tomek A, Pya Y, Bekbossynova M, Kim MH. Inferiority of ticagrelor in the PHILO trial: play of chance in East Asians or nightmare confirmation of PLATO-USA? Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:372-376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schüpke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, et al. ; ISAR-REACT 5 Trial Investigators . Ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1524-1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sukul D, Seth M, Dixon SR, Khandelwal A, LaLonde TA, Gurm HS. Contemporary trends and outcomes associated with the preprocedural use of oral P2Y12 inhibitors in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2). J Invasive Cardiol. 2017;29(10):340-351. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00094.Serotonin [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katayama Y, Kubo T, Ino Y, et al. The relationship between timing of prasugrel pretreatment and in-stent thrombus immediately after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome: an optical coherence tomography study. Heart Vessels. 2018;33(10):1159-1167. doi: 10.1007/s00380-018-1167-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Yamaji K, et al. ; J-PCI Registry Investigators . Impact of institutional and operator volume on short-term outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the Japanese Nationwide Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(9):918-927. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. ; ACC/AHA Task Force Members; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):2354-2394. Published correction appears in Circulation. 2014;130(25):e431-e432. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montalescot G, Bolognese L, Dudek D, et al. ; ACCOAST Investigators . Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(11):999-1010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiomi H, Morimoto T, Makiyama T, et al. ; CREDO-Kyoto Investigators . Evolution in practice patterns and long-term outcomes of coronary revascularization from bare-metal stent era to drug-eluting stent era in Japan. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(10):1652-1659. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin in high-risk patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2032-2042. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Jüni P, et al. ; GLOBAL LEADERS Investigators . Ticagrelor plus aspirin for 1 month, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months vs aspirin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor for 12 months, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months after implantation of a drug-eluting stent: a multicentre, open-label, randomised superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):940-949. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31858-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehran R, Pocock SJ, Stone GW, et al. Associations of major bleeding and myocardial infarction with the incidence and timing of mortality in patients presenting with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a risk model from the ACUITY trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(12):1457-1466. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ndrepepa G, Schuster T, Hadamitzky M, et al. Validation of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium definition of bleeding in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2012;125(11):1424-1431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Details Regarding Variable Definitions

eAppendix 2. Variables Included in the Propensity Score

eAppendix 3. Factors Regarding Pre-Specified Subgroup Analyses

eFigure 1. Study Flowchart

eFigure 2. Time Trend of Low-Dose Prasugrel Use and Crude Incidence of Bleeding Events in High Bleeding Risk Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome

eFigure 3. Time Trend of Low-dose Prasugrel Use and Crude Incidence of Bleeding Events in Low Bleeding Risk Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome

eFigure 4. Histogram of Propensity Score Distribution for Prasugrel and Clopidogrel

eFigure 5. Standardized Mean Differences Before and After Propensity Score Matching