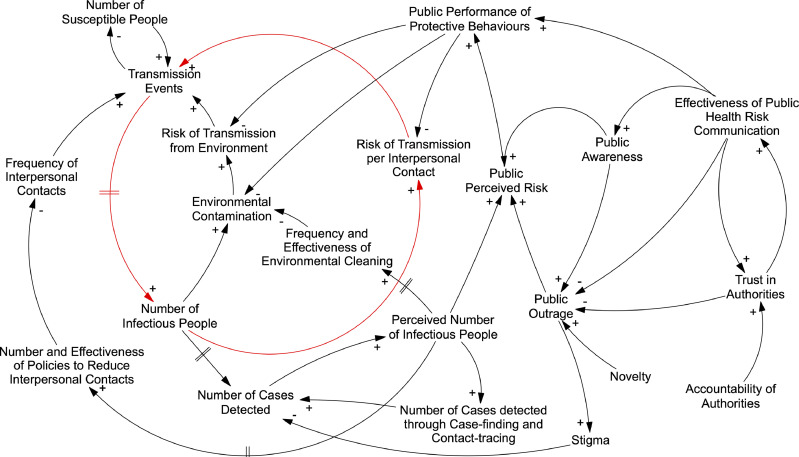

A novel zoonotic coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 has resulted in a pandemic of respiratory infection [1,2]. COVID-19 has provoked restrictive infection control measures, social and economic disruption, and expressions of racism [3]. Systems thinking can help policymakers understand and influence the spread of infection and its multifaceted consequences across the community since society is itself a complex adaptive system [4]. It can provide a framework to look beyond the chain of infection and better understand the multiple implications of decisions and (in)actions in face of such a complex situation involving many interconnected factors. Causal loop diagrams (CLDs) are tools to depict the causal connections between components of a system, and illustrate how changes in one component cascade in changes in others and back to itself, via feedback loops, potentially affecting the status of the entire system [5]. Fig. 1 presents a simple CLD as an example of some important interacting components in a society that is responding to the threat of COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

An example causal loop diagram illustrating some of the interacting components in a society responding to the threat of COVID-19.

A reinforcing feedback loop is responsible for causing exponential growth in the number of infected people (in red). However, the risk of transmission (often expressed as the basic reproduction number, R0) is seen to be a factor of the context, not simply a characteristic of the virus, resulting from a long chain of dynamic interactions involving components otherwise seen as distant or disconnected, such as the public's trust in authorities and stigma.

Risk communication influences people's capability and motivation to perform protective behaviours. However, public alarm about a novel hazard and low trust in authorities may result in ‘outrage’ [6]. In our illustrative CLD, this may give rise to stigma, reducing detection of infectious people, and therefore reducing the intensity of individual and societal responses. As the novelty of the situation declines, so may outrage, risk perception and individual protective behaviours.

Delays in information flows (and thus corrective actions) reduce controllability in dynamic systems [5,7]. There are time delays between people being infected and becoming infectious, being detected, and the introduction of control measures. Therefore, the response will lag behind the true number of cases. Given exponential growth in outbreaks, a later response will need more effort than an early one to be successful. The delayed effects of control measures on the number of detected cases will cause uncertainty about their effectiveness, risking over-reaction.

Another important feedback loop is present in our CLD: when the perceived number of infectious people begins to drop (due to control measures or the impaired ability to test and detect new cases, for example), personal and societal measures to control the infection will be relaxed, increasing transmission, and oscillating periods of re-emergence of the disease and subsequent return of control measures may occur.

System behaviour is caused by system structure [6]. Visualising the system can help us change the structural connections to achieve our goals. If desirable protective measures are separated from their dependence on the perceived number of infectious people, they could be used to pre-emptively reduce the risk of transmission in the absence of the infectious agent. Policies that reduce the number of interpersonal contacts and environmental contamination do not need to motivate people's own protective behaviours, and can therefore avoid the risk of outrage and stigma. Examples of such policies include promoting work from home, flexible or staggered working hours, increasing opportunities to prevent environmental contamination (e.g. better access to hand washing or sanitation facilities), increased cleaning of shared spaces [8], mitigating economic pressure for people to work while infectious, natural ventilation [9], and improving sanitation and food hygiene [10]. In common, these actions rely less on individuals’ agency by providing a protective context. Finding ways to incorporate and sustain such changes could reduce the risk of future outbreaks, the incidence of seasonal influenza and other infections, and even the carbon footprints of travel and air conditioning. The rapid spread of COVID-19 demonstrates the need to support risk reduction through system change globally, not only to respond after new threats emerge. The sporadic nature of outbreaks means that in the time between outbreaks, it is not evident when the conditions in the system are conducive or resistant to the spread of infection. In responding to the COVID-19 epidemic, policymakers should aim to bring about protective structural system changes so that the readiness of society to prevent emerging infectious disease outbreaks is independent of the current perceived number of cases. In doing so, they can create a system that is intrinsically more resilient to new, and established, infectious agents. Systems thinking and methods can help achieve this.

Disclosure statement

Dr Bradley is jointly employed by Queen's University Belfast and the Public Health Agency (PHA), Northern Ireland. PHA is the regional body responsible for public health in Northern Ireland.

Dr. Mansouri reports grants from Kuwait Civil Services Commission, during the conduct of the study; and Dr Mansouri has been employed by the Ministry of Health, Kuwait and has worked with the World Health Organization on outbreak preparedness and response.

Professor Kee is jointly employed by Queen's University Belfast and the Public Health Agency (PHA), Northern Ireland. PHA is the regional body responsible for public health in Northern Ireland.

Dr. Garcia has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020 (accessed March 11, 2020).

- 3.Habibi R., Burci G.L., de Campos T.C. Do not violate the International Health Regulations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:664–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30373-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Luke D.A., Stamatakis K.A. System science methods in public health: dynamics, networks, and agents. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:357–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkwood CW. System dynamics methods: a quick introduction. 1998. http://www.public.asu.edu/∼kirkwood/sysdyn/SDIntro/SDIntro.htm.

- 6.Sandman PM. Responding to community outrage: strategies for effective risk communication. 2012.

- 7.Feng S., Chen M., Zhan N., Fränzle M., Xue B. Taming delays in dynamical systems. In: Dillig I., Tasiran S., editors. Computer aided verification. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2019. pp. 650–669. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampf G., Todt D., Pfaender S., Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkinson J, Chartier Y, Lúcia Pessoa-Silva C, Jensen P, Li Y, Seto W-H. Natural ventilation for infection control in health-care settings. 2009 http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/natural_ventilation.pdf. [PubMed]

- 10.Yeo C., Kaushal S., Yeo D. Enteric involvement of coronaviruses: is faecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 possible? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30048-0. published online Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]