Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can serve as life-saving rescue therapy for refractory respiratory failure in the setting of acute respiratory distress syndrome, such as that induced by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In the study by Yang and colleagues,1 who compared clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19, five (83%) of six patients receiving ECMO died. Although this sample was small, and specific baseline characteristics and disease courses were almost unknown, it raises concerns about potential harms of ECMO therapy for COVID-19.

Lymphocyte count has been associated with increased disease severity in COVID-19.1, 2 Patients who died from COVID-19 are reported to have had significantly lower lymphocyte counts than survivors.2 As such, we need to consider the potential compounding immunological insults involved with initiation of an extracorporeal circuit in these patients. During ECMO, substantial decreases in the number and function of some populations of lymphocytes is commonplace.3 As it might be hypothesised that repletion of lymphocytes could be key to recovery from COVID-19, lymphocyte count should be closely monitored in these patients receiving ECMO.

Ruan and colleagues2 also showed that interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentrations differed significantly between survivors and non-survivors of COVID-19, with non-survivors having up to 1·7-times higher values. During ECMO, IL-6 concentrations are consistently elevated and inversely correlated with survival in children and adults.4 Those that survived ECMO were able to normalise their IL-6 concentrations, whereas those that died had persistently elevated values. Moreover, elevated IL-6 concentrations in lung induced by initiation of ECMO have been convincingly shown to be associated with parenchymal damage in animal models of venovenous ECMO.5

While not to discourage the use of ECMO, based on the abovementioned observations, the immunological status of patients should be considered when selecting candidates for ECMO. More reports are needed to understand the potential benefits or harms of extracorporeal life support in severe COVID-19 and future authors should be encouraged to provide more data for this subset of patients. Lastly, clinicians should consider tracking both lymphocyte count and IL-6 during ECMO to monitor patient status and prognosis.

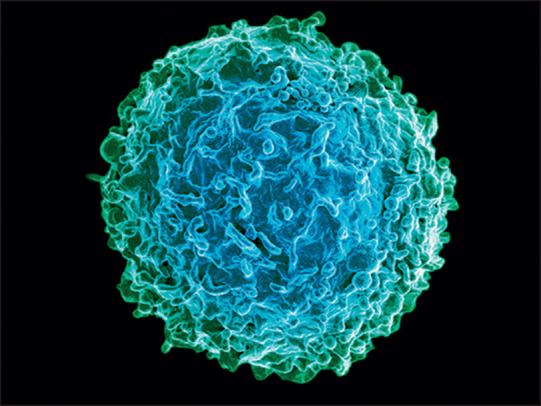

© 2020 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health/Science Photo Library

Acknowledgments

I declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. published online Feb 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. published March 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bizzarro MJ, Conrad SA, Kaufman DA, Rycus P. Infections acquired during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in neonates, children, and adults. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:277–281. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e28894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risnes I, Wagner K, Ueland T, Mollnes T, Aukrust P, Svennevig J. Interleukin-6 may predict survival in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment. Perfusion. 2008;23:173–178. doi: 10.1177/0267659108097882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi J, Chen Q, Yu W. Continuous renal replacement therapy reduces the systemic and pulmonary inflammation induced by venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a porcine model. Artif Organs. 2014;38:215–223. doi: 10.1111/aor.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]