See Related Article, page 412

The onslaught of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)‒associated disease that developed in 2019, COVID-19, has gripped the world in a pandemic and challenged the culture, economy, and healthcare infrastructure of its population. It has become increasingly important that health systems and their clinicians adopt a universal consolidated framework to recognize the staged progression of COVID-19 illness to deploy and investigate targeted therapy likely to save lives. The largest report of COVID-19 from the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention summarized findings from 72,314 cases and noted that although 81% were of a mild nature with an overall case fatality rate of 2.3%, a small sub-group of 5% presented with respiratory failure, septic shock, and multiorgan dysfunction, resulting in fatality in 50% of such cases, a finding that suggests that it is within this group that the opportunity for life saving measures may be most pertinent.1 Once the disease is manifest, supportive measures are initiated with quarantines; however, a systematic disease modifying therapeutic approach remains empirical. Pharmacotherapy targeted against the virus holds the greatest promise when applied early in the course of the illness, but its usefulness in advanced stages may be doubtful.2 , 3 Similarly, use of anti-inflammatory therapy applied too early may not be necessary and could even provoke viral replication, such as in the case of corticosteroids.4 It seems that there are 2 distinct but overlapping pathologic subsets; the first triggered by the virus itself and the second by the host response. Whether in native state, immunoquiescent state as in the elderly, or immunosuppressed state as in heart transplantation, the disease tends to present and follow these 2 phases, albeit in different levels of severity. The early reports in heart transplantation suggest that symptom expression during the phase of establishment of infection are similar to non-immunosuppressed individuals; however, in limited series, the second wave determined by the host inflammatory response seems to be milder, possibly owing to the concomitant use of immunomodulatory drugs.5 , 6 Similarly, an epidemiologic study from Wuhan, China, in a cohort of 87 patients suggests that precautionary measures of social distancing, sanitization, and general hygiene allow heart transplant recipients to experience a low rate of COVID-19 illness.7 Of course, we do not know whether they are asymptomatic carriers because in this survey-based study, universal testing during the early 3 months was not employed. One interesting fact in this study was that many heart transplant recipients have hematologic changes of lymphopenia because of the effects of immunosuppressive therapy, which may obfuscate the laboratory interpretation of infection in such patients, should they get infected.

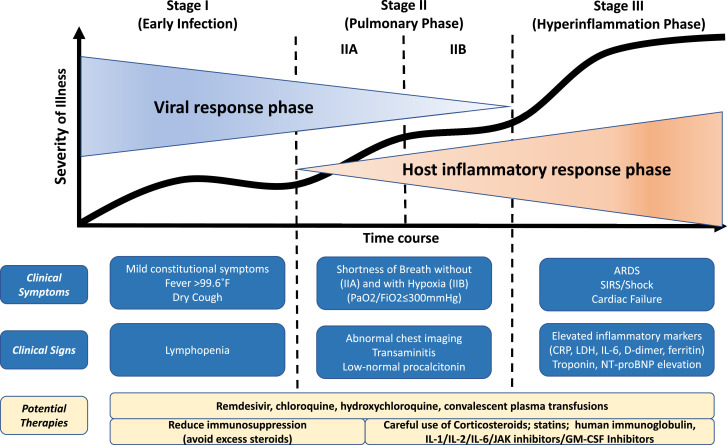

Much confusion abounds in the therapeutic tactics employed in COVID-19. It is imperative that a structured approach to clinical phenotyping be undertaken to distinguish the phase where the viral pathogenicity is dominant versus when the host inflammatory response overtakes the pathology. In this editorial, we propose a clinical staging system to establish a standardized nomenclature for uniform evaluation and reporting of this disease to facilitate therapeutic application and evaluate response. We propose the use of a 3-stage classification system, recognizing that COVID-19 illness exhibits 3 grades of increasing severity, which correspond with distinct clinical findings, response to therapy, and clinical outcome (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Classification of COVID-19 disease states and potential therapeutic targets. The figure illustrates 3 escalating phases of COVID-19 disease progression, with associated signs, symptoms, and potential phase-specific therapies. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CRP, C-reactive protein; JAK, janus kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; GM-CSF, Granulocyte Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor.

Stage I (mild)—early infection

The initial stage occurs at the time of inoculation and early establishment of disease. For most people, this involves an incubation period associated with mild and often non-specific symptoms, such as malaise, fever, and a dry cough. During this period, SARS-CoV-2 multiplies and establishes residence in the host, primarily focusing on the respiratory system. Similar to its older relative, SARS-CoV (responsible for the 2002–2003 SARS outbreak), SARS-CoV-2 binds to its target using the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor on human cells.8 These receptors are abundantly present on human lung and small intestine epithelium and the vascular endothelium. As a result of the airborne method of transmission and affinity for pulmonary angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors, the infection usually presents with mild respiratory and systemic symptoms. Diagnosis at this stage includes respiratory sample polymerase chain reaction, serum testing for SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM, chest imaging, complete blood count, and liver function tests. Complete blood count may reveal a lymphopenia and neutrophilia without other significant abnormalities. Treatment at this stage is primarily targeted toward symptomatic relief. Should a viable anti-viral therapy, such as remdesivir, be proven beneficial, targeting selected patients during this stage may reduce duration of symptoms, minimize contagiousness, and prevent progression of severity. In patients who can keep the virus limited to this stage of COVID-19, prognosis and recovery are excellent.

Stage II (moderate)—pulmonary involvement (IIa) without and (IIb) with hypoxia

In the second stage of established pulmonary disease, viral multiplication and localized inflammation in the lung are the norm. During this stage, patients develop a viral pneumonia, with cough, fever, and possibly hypoxia (defined as PaO2/FiO2 < 300 mm Hg). Imaging with chest roentgenogram or computed tomography reveals bilateral infiltrates or ground glass opacities. Blood tests reveal increasing lymphopenia, along with transaminitis. Markers of systemic inflammation may be elevated, but not remarkably so. It is at this stage that most patients with COVID-19 would need to be hospitalized for close observation and management. Treatment would primarily consist of supportive measures and available anti-viral therapies such as remdesivir (available under compassionate and trial use). It should be noted that serum procalcitonin is low to normal in most cases of COVID-19 pneumonia. In early Stage II (without significant hypoxia), the use of corticosteroids in patients with COVID-19 may be avoided.4 However, if hypoxia ensues, it is likely that patients will progress to requiring mechanical ventilation, and in that situation, we believe that the use of anti-inflammatory therapy such as with corticosteroids may be useful and can be judiciously employed. Thus, Stage II disease should be sub-divided into Stage IIa (without hypoxia) and Stage IIb (with hypoxia).

Stage III (severe)—systemic hyperinflammation

A minority of COVID-19 patients will transition into the third and most severe stage of the illness, which manifests as an extrapulmonary systemic hyperinflammation syndrome. In this stage, markers of systemic inflammation seem to be elevated. COVID-19 infection results in a decrease in helper, suppressor, and regulatory T cell counts.9 Studies have revealed that inflammatory cytokines and biomarkers such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α, tumor necrosis factor-α, C-reactive protein, ferritin, and D-dimer are significantly elevated in those patients with more severe disease.10 Troponin and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide can also be elevated. A form akin to secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis may occur in patients in this advanced stage of the disease.11 In this stage, shock, vasoplegia, respiratory failure, and even cardiopulmonary collapse are discernable. Systemic organ involvement, even myocarditis, would manifest during this stage. Tailored therapy in Stage III hinges on the use of immunomodulatory agents to reduce systemic inflammation before it overwhelmingly results in multiorgan dysfunction. In this phase, use of corticosteroids may be justified in concert with the use of cytokine inhibitors such as tocilizumab (IL-6 inhibitor) or anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist).11 Intravenous immune globulin may also play a role in modulating an immune system that is in a hyperinflammatory state. Overall, the prognosis and recovery from this critical stage of the illness are poor, and rapid recognition and deployment of such therapy may have the greatest yield.

The first open-label randomized controlled clinical trial of anti-viral therapy was recently reported.3 In this study, 199 patients were randomly allocated to the anti-viral agents lopinavir–ritonavir or to standard of care, and this regimen was not found to be particularly effective. One reason for this may have been that the patients were enrolled during the pulmonary stage with hypoxia (Stage IIb) when the viral pathogenicity may have been only one lesser dominant aspect of the overall pathophysiology, and host inflammatory responses were the predominant pathophysiology. We believe that this proposed 3-stage classification system for COVID-19 illness will serve to develop a uniform scaffold to build structured therapeutic experience in patients with or without transplantation as healthcare systems globally are besieged by this crisis.

Disclosure statement

Dr Siddiqi has no conflict of interest to declare. Dr Mehra reports no direct conflicts pertinent to the development of this paper. Other general conflicts include consulting relationships with Abbott, Medtronic, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Mesoblast, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, NupulseCV, FineHeart, Leviticus, and Triple Gene.

References

- 1.Novel coronavirus pneumonia emergency response epidemiology team The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China [in Chinese] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19 [e-pub ahead of print]. N Engl J Med doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282, Accessed March 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395:473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F, Cai J, Dong N. First cases of COVID-19 in heart transplantation From China. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:418–419. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aslam S, Mehra MR. COVID-19: yet another coronavirus challenge in transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:408–409. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren Z-L, Hu R, Wang Z-W. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of heart transplant recipients during the 2019 coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China: a descriptive survey report. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.008. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. e00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China [e-pub ahead of print]. Clin Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248, Accessed March 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China [e-pub ahead of print]. JAMA Intern Med doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994, Accessed March 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M,et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression [e-pub ahead of print]. Lancet doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0, Accessed March 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]