Dear Editor,

The 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The virus was first reported in Wuhan, Hubei, China, in December 2019. After the lockdown of Wuhan and Hubei, the Taiwanese government planned to evacuate its citizens from the area by means of chartered flights. Out of the 47 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported in Taiwan by March 10 2020, 21 were imported. A detailed evacuation workflow was planned in order to minimize the possibility of surface environmental contamination1 - Preflight: (1) Equipment/facilities. (2) Regulation/communication. (3) Training/drills. Upon arrival at Wuhan airport: (1) Quarantine certification. (2) Self-report medical declaration. (3) Physical evaluation. Boarding: (1) Disinfection. (2) Protective clothing. (3) Boarding priority/seat arrangement. (Fig. 1 ) Inflight: (1) No inflight service. (2) Waste handling. (3) Monitor/seat-rearrangement. Upon arrival at Taiwan airport: (1) Disembark order. (2) Transport/self-health management.

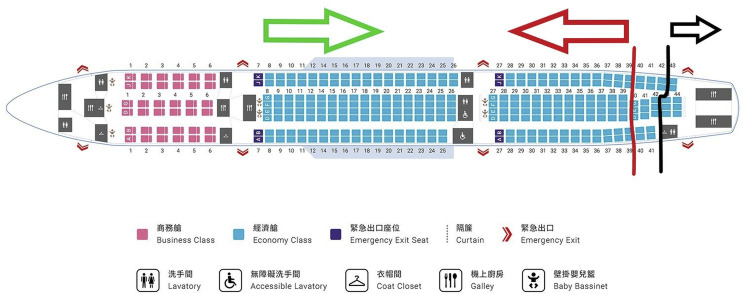

Figure 1.

Boarding priority & seat arrangement (Airbus A330 – 300) – Evacuees with black stickers boarded first and were seated from row 43 backwards. The next was the red group from row 39 onwards, then the green group from row 7 backwards, and finally the medical staff from row 6 onwards.

On March 10 2020, Taiwan evacuated her second batch of citizens from Wuhan. A specialized medical team consisting of 4 physicians and 9 registered nurses was organized. Before flight, the medical team and their equipment were examined in detail. All the medical staff were equipped with personal protective gear (protective coveralls, face shield, N95 mask, gloves) and these remained donned throughout the mission.

At Wuhan airport, the evacuees were first screened by the mission nurse using an infrared thermometer. If their forehead temperature was 37.4 °C or more, it would be rechecked using an ear thermometer. If the second reading was still ≧ 37.4 °C, he/she was considered to be “febrile” and excluded from the evacuation.

Only afebrile evacuees would proceed to have their quarantine certification and self-report medical declaration verified by the medical team, following which they would be examined by the doctors. In addition to being febrile, other conditions that would lead to a denial of evacuation included (i) active respiratory symptoms with an oxygen saturation ≦ 95% on pulse oximetry or abnormal respiratory examination findings, (ii) general physical condition that is not suitable for flight, and (iii) a pre-existing diagnosis of COVID-19 for which the evacuee may be receiving treatment, or still pending insolation or quarantine.

Those who were well on examination (afebrile with a pulse oximetry reading of ≧ 95% and unremarkable pulmonary examination), and free of fever and respiratory symptoms for the preceding 14 days, were identified with a green sticker. Red stickers were used to identify evacuees who were well on examination, but had declared that they had fever or respiratory symptoms in the past 14 days. The third group of evacuees, identified by black stickers, consisted of those who were afebrile, but experienced any kind of respiratory symptoms at the point of examination.

After completing screening by the medical team, evacuees were instructed to disinfect both hands and wear personal protective equipment (protective gown, face shield, surgical mask and gloves) before being allowed to board the aircraft. The boarding sequence was based on their color labels. Evacuees with black stickers boarded first and were seated towards the back of the plane, from row 43 backwards. The next group to board was the red group, and finally the green. Two seats were left vacant between each passenger. During the flight, people were asked not to talk to each other, and not to consume food and drinks. Leaving their seats to go to the toilet was not allowed. Evacuees were advised to inform the medical staff if they experienced any discomfort. After landing in Taiwan, all evacuees were examined again. The throat swab samples were collected and underwent real-time polymerase-chain-reaction test by the local quarantine officers before being transported separately to designated dormitories for 14 days of self-quarantine. All of 361 evacuees were proved to be negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection later.

While the risk remains that asymptomatic evacuees may transmit the disease,2 countries may still be obliged to evacuate these citizens from epidemic areas that have been locked down. We hope to share certain insights derived by the Taiwanese medical team during the execution of our evacuation. Our experience was limited to a short-haul flight – it takes around 3 h to travel from Wuhan to Taiwan. For flights of longer duration, there needs to be allowances made for food, beverage, and toileting needs.3 Indeed, given the restrictions imposed during the flight, certain high-risk populations, for example people who are prone to developing deep venous thrombosis or neuropsychiatric-related conditions,4 may require special precautions or medical attention. Another limitation was our workflow could not show preventive efficacy for environmental contamination or diseases transmission for SARS-CoV-2 infected evacuees. In addition, an isolation unit should be considered for in-flight emergencies or isolation.3 , 5

References

- 1.Ong S.W.X., Tan Y.K., Chia P.Y., Lee T.H., Ng O.T., Wong M.S.Y. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. Jama. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbs S.G., Herstein J.J., Le A.B., Beam E.L., Cieslak T.J., Lawler J.V. Review of literature for air medical evacuation high-level containment transport. Air Med J. 2019;38:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szilard I., Cserti A., Hoxha R., Gorbacheva O., O'Rourke T. International organization for migration: experience on the need for medical evacuation of refugees during the Kosovo crisis in 1999. Croat Med J. 2002;43:195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai S.H., Tsang C.M., Wu H.R., Lu L.H., Pai Y.C., Olsen M. Transporting patient with suspected SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1325–1326. doi: 10.3201/1007.030608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]