To the Editor:

The arrival of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic to Europe introduced a new scenario in the differential diagnosis of infectious diseases that pathologists may encounter in cytologic specimens, such as those in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Owing to the urgent turnaround time that the clinical contest of these particular tests requires, we would like to report to clinicians the following peculiar findings, adding them to the previously published list of pathologic findings related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.1 On February 17, a 66-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department of a hospital in the north of Italy with a 2-day history of fatigue and fever. He had no respiratory symptoms, and his chest radiograph result was negative. The day after, he progressively developed respiratory distress and hypoxia, and a new chest radiograph image revealed bilateral infiltrates. After a failed noninvasive ventilation trial, he was sedated and endotracheally intubated. Computed tomography scan images revealed bilateral consolidation with ground-glass attenuation in the nondependent areas. Progressive worsening of hypoxemia (up to 47 mm Hg of the ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen) was also observed in the patient. Our Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation team was called to retrieve the patient. The patient was transferred to our institution after starting venovenous extracorporeal support. Real-time polymerase chain reaction on BAL specimen revealed positivity for SARS-CoV-2. The BAL specimen was sent for pathologic examination as well (Fig. 1 A). The fluid was cytospinned and stained by May-Grünwald-Giemsa, Papanicolaou, and Perls (Prussian blue) methods. A cell block was produced for immunohistochemical staining (CD3, CD138, CD20, and kappa and lambda immunoglobulin light chains on a Dako Omnis platform, Glostrup, Denmark). The morphologic analysis revealed fibrino-hematic material with scattered alveolar macrophages and a predominantly large number of activated plasma cells (CD138+, Fig.1 C,D) with occasional plasmablastic features, admixed with T lymphocytes (CD3+) and scattered B cells (CD20+). Desquamated pneumocytes, multinucleated syncytial cells, and hyaline material were not appreciated; however, occasional alveolar macrophages revealing nuclear clearing or intranuclear cytopathic inclusions attributable to SARS-CoV-2 were easily found (Fig. 1 B). Common morphologic features of viral infection include cytomegaly, syncytia formation, and intracytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusions, but different viruses (adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, parainfluenza, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella-zoster virus, and measles) may cause overlapping cytomorphologic changes.2 In 2009 influenza A virus subtype H1N1 pneumonia associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome, cells with eccentric nuclei and paranuclear vacuole were described; however, those cells proved to be reactive immature type II pneumocytes (CD138−) under electron microscopy, probably with a reparative role.3 In the COVID-19 BAL specimen, dramatically activated plasma cells revoked immune elements frequently found in extrinsic allergic alveolitis, drug-induced pneumonia, aspergillosis, and specific subgroups of lymphomas, such as lymphomatoid granulomatosis or primary effusion lymphoma. At the moment, there are no specific therapeutics approved by the Food and Drug Administration, but the peculiar abundance of CD138+ plasma cells in COVID-19 may be a relevant feature; indeed COVID-19 and SARS, both caused by coronaviruses, are characterized by an overexuberant inflammatory response. On the basis of this finding, the empiric combined use of antivirals and anti-inflammatory drugs is under study, even though previous studies on the 2009 influenza A virus subtype H1N1 have not reported evidence of beneficial effects of corticosteroids, which are often administered to patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to viral pneumonia.4 , 5

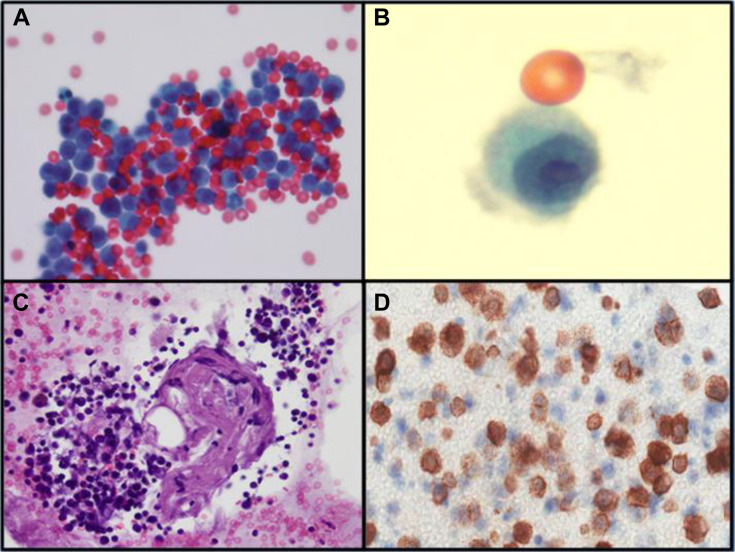

Figure 1.

(A) Cytospin of coronavirus disease 2019 bronchoalveolar lavage specimen revealing many clusters of activated plasma cells (Papanicolaou, ×40). (B) Alveolar macrophage intranuclear cytopathic inclusion in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (Papanicolaou, ×100, courtesy of Dr. Francesca Bono). (C, D) Groups of polyclonal CD138-positive plasma cells (cell block, hematoxylin and eosin, ×20; CD138 staining, ×40).

References

- 1.Tian S., Hu W., Niu L., Liu H., Xu H., Xiao S.Y. Pulmonary pathology of early phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer [e-pub ahead of print]. J Thorac Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010 accessed March 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Baldassarri R.J., Kumar D., Baldassarri S., Cai G. Diagnosis of infectious diseases in the lower respiratory tract: a cytopathologist’s perspective. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:683–694. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0573-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grasselli G., Foti G., Patroniti N. A case of ARDS associated with influenza A - H1N1 infection treated with extracorporeal respiratory support. Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75:741–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brun-Buisson C., Richard J.C., Mercat A., Thiébaut A.C., Brochard L., REVA-SRLF A/H1N1v 2009 Registry Group Early corticosteroids in severe influenza A/H1N1 pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1200–1206. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0135OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stebbing J., Phelan A., Griffin I. COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments [e-pub ahead of print]. Lancet Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30132-8 accessed March 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]