The UK Public Health Association's 2004 Annual Forum hosted the Congress of the World Federation of Public Health Associations over four days in Brighton. This unique event attracted some 1200 delegates from over 50 countries. The theme of the conference, sustainable communities in a global context, offered a platform for a wide range of plenary and parallel sessions led by invited speakers, including public health leaders and government ministers. In the words of one of the speakers, health has been positioned ‘as a defining characteristic of the global society of the 21st century’. All the plenary speakers touched upon this theme. This issue of Public Health is devoted to their presentations, most of which have been revised especially for publication.

A theme of many of the presentations was the increasing influence of markets, or quasi-markets, on global health status, and the close relationship between good health and good economics. Rafael Bengoa, Director of Health System Policies and Operations with the World Health Organization, points out that the global situation in the early 21st century is very different from the time of the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978 which promoted the idea of primary care-led health systems. Whatever benefits economic growth has provided, it has brought in its wake a trail of deleterious effects and chronic disease burdens which are only now accepted by governments desperately trying to find solutions to new pandemics like rising levels of obesity, sexually transmitted diseases and mental illness. An illustration of the insidious effects of the unrestrained marketisation of public policy is the mounting export trade in tobacco products from the developed to developing worlds.

Alongside these man-made afflictions has been the sheer difficulty of orchestrating a worldwide response to the new global epidemics, most visibly HIV/AIDS which is projected to rise by 20% by 2010 before it begins to decline but not before it wrecks the economic and social infrastructure of much of Africa and Asia, notably India. In the words of Richard Feachem, Head of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, HIV/AIDS is ‘the greatest disaster in recorded human history’. Defeating this epidemic is dependent on three preconditions: leadership, technology and money. He remains hopeful that they will be in place in time to arrest the epidemic though not before the viability of states is put in jeopardy.

The UK Minister for International Development, Hilary Benn, notes the significance of poverty as a factor in the epidemics sweeping parts of central and eastern Europe (where David Byrne, European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Protection, notes that in some countries AIDS is spreading faster than in sub Saharan Africa). The most effective way to reduce their impact in poor countries is to reduce poverty and strengthen health systems. The Millennium Development Goals provide the framework for such a strategy.

In responding to these trends and threats, Bengoa suggests that declarations and strategies like Alma Ata and Health for All are even more necessary to counter the anti-health forces evident in all countries. At the heart of such initiatives are notions of greater public participation and intersectoral action. Without these, finding sustainable solutions to health scourges will be unlikely.

Faced with these health threats, some new and others not so new, the public health community must learn new ways of confronting them. The path-breaking Framework Convention on Tobacco Control is an example of the type of approach needed and provides a model of what might be done in working with the food industry to control foods high in sugar and salt.

The problems of lack of leadership, advocacy and capacity in the public health workforce constitute another key theme running through many of the presentations. Derek Wanless, advisor to the UK Treasury, is critical of public health for punching well below its weight. He provides a robust defence of his review of public health in the UK, noting that after 30 years of failed attempts to make the National Health Service a health rather than a sickness service those working in public health had to share some of the responsibility. Unless they did, then implementing the ‘fully engaged scenario’, which entailed a step change in respect of the importance of public health in driving health policy, would prove impossible and resources would continue to be poured into the NHS simply in order to stand still. Wanless does not think the government could afford to ignore public health since the NHS would be unable to cope with the rising demand of ill-health unless an upstream preventive approach is given significant political and managerial support. Ultimately, good health is good economics—a healthy workforce is a more productive one. The importance of such thinking lies in an acknowledgement that investing in health is no longer regarded as bad economics or poor investment.

Marc Danzon, WHO Regional Director for Europe, challenges the assumption that good health axiomatically equals good economics, pointing out that it is quite possible to have a successful economy that is at the expense of good health. For many people such an ideal relationship between economics and health is simply not an option. Perhaps, too, there is a need to challenge the current ‘growth fetish’ and to question whether the preoccupation with improved productivity and higher levels of growth is either desirable or good for health.

Both Wanless and Ilona Kickbusch, currently based in the School of Medicine at Yale University, make observations on the end of public health as we know it. Neither laments such a development on the grounds that it is overdue since hitherto much investment in public health has little to show for it. Indeed, Wanless questions whether the term ‘public health’ is still appropriate and sufficiently inclusive for the domain of prevention as distinct from health promotion. Kickbusch holds those ostensibly leading public health responsible claiming that they have lost the passion in public health together with important political and advocacy skills. The approach to public health had to change so that it became fully engaged in the political and social arena.

Kickbusch calls for global action in five areas:

-

•

Health as a global public good

-

•

Health as a key component of global security

-

•

Health as a key factor of global governance for interdependence

-

•

Health as responsible business practice and social responsibility

-

•

Health as global citizenship.

By the end of the conference these action areas had become known as the Brighton Declaration with a commitment that future UKPHA and World Federation conferences would revisit them in order to assess and audit progress in their implementation. The general consensus among speakers and delegates, and reflected in the papers selected for this issue, was that we know what the problems and challenges are. It is now essential to act and make sustainable inroads into them.

An underlying message from the Brighton conference is that a louder global voice for public health must be found. But before this can happen, public health has to be repoliticised and adopt an advocacy stance akin to the deeds of its founders over 150 years ago. If we are witnessing a renaissance of public health around the world, as many speakers believed to be the case, then it is essential that we do not squander the opportunities presented. The papers in this collection show clearly what needs to be done to avoid such an outcome and also what will happen if we fail.

2. The Leavell lecture—The end of public health as we know it: constructing global public health in the 21st century☆ Ilona Kickbusch

2.1. Health lies at the core

Health lies at the very core of modernity and development. It has shaped the nature of the modern nation state and its social institutions. Health has powered social movements, defined rights of citizenship and contributed to the construction of the modern self and its aspirations in the developed world—and is increasingly gaining a similar role in developing countries. The success of public health has changed the very nature of developed societies. They have become health societies, defined by five major characteristics:

-

•

a high life expectancy and ageing populations

-

•

an expansive health and medical care system

-

•

a rapidly growing private health market

-

•

health as a dominant theme in social and political discourse

-

•

health as a major personal goal in life.

Each of these five characteristics, and perhaps even more their synergies, are changing the face of public health and the extent of its remit. Two key dimensions emerge as driving forces: do-ability and expansion of territory and with it a significant number of new public health actors. As in the 19th and 20th centuries, public health action will define progress not only for health but for the social and economic systems of 21st century society. How will we treat the old? How will we pay for health? Who has a right to care? To what extent will we enhance our biological capabilities? All these questions are not just about health, they are about our way of life, about social justice and about solidarity. The political dimensions of these developments are only beginning to be understood in their full implications, and their impact is no longer limited to the developed world. Increasingly public health is challenged to:

-

•

act in new policy arenas: trade, industry, international law, foreign policy to name but a few

-

•

move beyond the classic areas of action into fields such as drug treatment, genetics and human rights

-

•

respond to the impacts of ever increasing privatization and commercialization of health and health services throughout the world.

The two public health revolutions that changed the face of health and disease in the industrialized countries in the 19th and 20th centuries, the control of infectious disease through protective health measures and the consequent battle against non-communicable disease, are still underway in differing degrees throughout the world. They are intertwined in new ways in many developing countries that now face new patterns of health and disease as well as longer life expectancy without the time and the resources to respond. And finally, with each of the public health revolutions come not only a change in disease patterns but also a significant cognitive shift that implies that health and disease are no longer natural states. Health has become do-able; solutions exist, be they medical, economic or social. With the advent of antiretroviral drugs, for example, HIV/AIDS is no longer a death sentence. The do-ability of treatment brings issues of availability and access to the fore, for the rich as well as the poor. It is this do-ability of health that increasingly drives the debate on human dignity, equity and social justice and raises new challenges for public health action.

The post-modern health societies of the developed world stand in stark contrast to the situation in the poorest countries. Poor countries (and poor excluded populations in more developed regions) face a stark reality:

-

•

a falling life expectancy in many African countries and some Eastern European Countries

-

•

a lack of access to even the most basic services

-

•

an excess of personal expenditures for health of the poorest

-

•

health as a neglected arena of national and development politics

-

•

health as a matter of survival.

The comparative statistics for maternal and child mortality for Canada and Haiti, two countries that are just a plane ride away in the same region of the WHO, are striking. According to the Pan-American Health Organization, the infant mortality rate is 5.1 in Canada and 97.1 in Haiti, and the under-five mortality rate is 16.5 times greater in Haiti than in Canada. The rate of maternal deaths is 35 times higher in Latin America and the Caribbean than in North America. The 40-year difference between the average life expectancy in Somalia and in Japan becomes unacceptable in the face of the do-ability of health. The public health focus on equity, access and health determinants must become increasingly global and examine more systematically how the public health response must be shared between the rich and the poor, between the international community and the nation states, the individual citizen and the state, the public and the private sector. It must develop new principles for public health action in a global world.

2.2. How committed is the developed world?

Health is on the global agenda. In the year 2000, the United Nations at its Millennium Summit adopted the Millennium Development Declaration,1 a set of eight goals to fight global poverty. A recent analysis by the Global Governance Initiative of the World Economic Forum, came to the conclusion that “the world is doing barely a third of what is necessary to fulfill the goals it has set.”2 The Initiative gives the world a score of four out of ten for the direct health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which aim to accomplish the following by 2015:

-

•

stop and begin to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other diseases

-

•

reduce by two thirds the under-five mortality rate

-

•

reduce by three quarters the maternal mortality ratio.

There is an increasing consensus that in order to affect change, development aid is necessary but totally insufficient and in need of a major overhaul. An index developed by the Center for Global Development, called the Commitment to Development Index, ranks 21 of the world's richest countries based on their commitment to broader policies that benefit the 5 billion people living in poorer nations. The index brings together seven issues: aid, trade, investment, migration, environment, security and technology and states: “no wealthy country lives up to its potential to help poor countries. Generosity and leadership remain in short supply.”3

Of course it is not only the international community that is at fault. In relation to HIV/AIDS, the report of the Global Governance Initiative puts the blame squarely at the door of the lack of support and leadership from the governments of affected countries.4 But bad governance in developing countries not withstanding, the overall history of development aid has contributed significantly to the present situation, from the approaches to aid as an instrument of the cold war, to the Bretton Woods enforcement of structural adjustment, to fads and fashions in the development business itself. Perverse effects of the system are increasing. For example, one of the unintended consequences of the influx of money for HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention is that doctors and nurses in Africa are abandoning the public sector in order to pursue internationally funded positions in HIV/AIDS programmes. Another is the lack of coordination of foreign aid, for example, a small country like Tanzania was faced with coordinating 1371 different projects funded by international aid agencies between 2000 and 2002.5

2.3. The expansion of actors and territory in global health

Just as the do-ability of health is one of the key driving forces of global health development so is its continuous expansion of actors and territory. At first sight it would seem that there is no reason to be concerned. Health issues have increased on agendas at all levels, from the foreign policies of nations to deliberations within the UN Security Council and General Assembly. Health has the richest foundation in the world—the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—on its side. The contribution to health in international donor aid has increased, particularly through the increased contributions to HIV/AIDS. With WHO, health has an intergovernmental agency that encompasses nearly all countries of the world.

The global health area has been transformed by a proliferation of actors, as indicated by the growth of civil society organizations (CSOs), the rise of trans national companies (TNCs), and the increasing involvement in health by organizations, such as the World Bank, regional development banks and regional organizations like the European Union. Since the 1980s, United Nations (UN) agencies besides WHO, such as UNICEF, UNDP, and UNFPA, have increasingly been dealing with health issues. This has been reinforced by a number of UN Summits that have included health goals in their major recommendations. New organizations, such as the Joint UN Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria have been created to take on health matters. Today a health programme run only by one organization is becoming the exception rather than the norm.

Health also has a multitude of institutions, partnerships and alliances, and it has spearheaded new ways for the public and private sector to work together. The UN Global Compact aims to ensure respect for human rights through the integration of such rights in business operations. Furthermore, UN agencies are increasingly involved in health initiatives that are conducted in partnership with many players and organizations. Finally health has benefited from the activists that have put health issues such as the access the antiretroviral drugs at the top of the anti-globalization agenda.

At the same time, there has been a continuous expansion of the territory of health. The Alma Ata Declaration opened the door to understand health in the context of development and reinforced the understanding of the first public health revolution that much of the most influential action to create health is found in sectors other than health. The notion of inter-sectoral action was the beginning of a new focus on health determinants. Over the last 20 years, research on socio-economic determinants of health has expanded and reinforced that the health care sector is only one of many sectors (i.e. transportation, housing, education, environment, etc.) that both affect and are affected by health.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 The WHO approach to health promotion reinforced this trend through programmes such as Healthy Cities. Most recently, the Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, ‘Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development’, underlined that health is a central component of poverty reduction and economic development of nations.11 It brought the health agenda firmly into the economic development agenda and close to ministries of finance. This was further strengthened by the prominence awarded to health in the MDGs. Yet the public health sector seems ill prepared to take a leading role in this very active arena which—because of the central role of health politically and economically—is increasingly defined by political rather than technical agendas.

2.4. The perfect storm

Beneath all this movement lies a serious global health crisis. It has six dimensions, which in turn represent the key challenges in health in the world during the next 10 years. While each of these dimensions is worrying enough in itself, the synergy between the six dimensions is creating ‘the perfect storm’. The weakening of public health at all levels of governance that has occurred over the last 30 years means that the public health establishment is not well prepared to deal with these major seminal trends occurring in relation to health and society. Indeed it raises the issue of to what extent the prevailing public health structures and policies can respond adequately to a totally new situation.

2.4.1. Dimension 1: the growth of epidemics

All social and economic development efforts manifest themselves in health outcomes, most importantly in better health and life expectancy. Increasingly, it is understood that health, in itself, is an important development factor.12 But increasingly there is no us and them any more in relation to infectious and non infectious diseases—both hit the developed and the developing world. The global AIDS epidemic confirms this. Societies that are losing their most productive adult population are also in danger of losing their stability and social cohesion. The economic impacts of the short-lived Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Canada and Asia have been significant. It is estimated that the economic toll of SARS has already reached $30 billion, largely from cancelled travel (thus impacting the service industry and airlines) and decreased investments.13

The developing world is not safe from the health threats of modern lifestyles, as illustrated by the global spread of the tobacco and obesity epidemics. Tobacco is responsible for about 5 million deaths each year, particularly among poor populations and countries. The obesity epidemic is spreading to low- and middle-income nations. WHO points to economic growth, modernization, urbanization, and globalization of food markets as some of the factors contributing to the epidemic.14 Approximately 177 million people are currently living with diabetes, and the number of people with the disease is projected to more than double by 2030, especially in developing nations.15

2.4.2. Dimension 2: the lack of sustainable health systems

The performance of health systems is a crucial component to promoting health and preventing disease. Failures of health systems disproportionately impact the poor, as they are given less respect, less choices of providers and lower quality amenities. The poor suffer from a lack of health care coverage and are forced to pay for their treatment, as privatization of health care spreads throughout the world. In India, for example, families pay 80% of their health costs out-of-pocket, compared to those in industrialized countries with universal health care who pay only 25% on average (with the US as an exception, where the average is 56%). Private sector provision of health care has grown in part due to lack of funding for public health services. According to WHO, nearly 20% of member states spend less that US$ 15 per capita on health, and health expenditures by the government are often heavily weighted towards tertiary care.16

Shortages of human resources plague the health systems of the developing world. The lack of health workers is impeding progress towards national health goals and the MDGs, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. In Botswana, for instance, insufficient health personnel have hindered free distribution of HIV/AIDS drugs. ‘Brain drain’ of health workers is weakening already fragile health systems. Although research on this migration is in its early stages, policy makers have identified it as a key impediment to a well functioning health system.17 In addition to human resources, health systems are also hindered by insufficient national capacities for public health in both rich and poor countries.

2.4.3. Dimension 3: the socio-economic-political context

Globalization greatly impacts the socio-economic-political context of health. At present, the poorest countries are feeling the devastating effects of global health disparities, but there are mounting signals that a new health divide is in the making in the developed world. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly difficult to define the rich and the poor of this world at the level of the nation state, as a large global underclass spreads out around the globe and defies old definitions of vulnerable groups. HIV/AIDS is only the most visible of the diseases of poverty that undermine the life chances of the poor. Developed countries are experiences cut back in services und public health programmes and the European model of social welfare states has come under significant attack. The nation state is less willing to regulate unhealthy goods and services with the consequence that the health society is an increasingly unequal society in terms of access to both prevention and treatment. If concepts of solidarity and universal access are weakened in the developed world, the chances for the developing world to benefit from global partnerships is significantly reduced.

2.4.4. Dimension 4: the values

The value base of global health action has become increasingly vague and unclear. The Health for All orientation of the 1980s was replaced with an investment in health perspective in the 1990s, headed by the World Bank, which brought an economic investment paradigm to the centre of the health debate. Since the end of the Cold War, health has become an integral part of the poverty reduction and social safety net strategies of the international community. In paradigmatic terms, this means that the acceptance of health as an end (as reflected in the human rights approach) has been overshadowed by the approach to health as a means.

There have been new attempts to embark on a debate as to which values should drive global health action. These values are reflected in discussions around the impact of globalization, human rights, global public goods (GPGs) and global social contracts. The debate on new global financing mechanisms is basically one about the values: According to what principles should wealth be shared at the global level?

2.4.5. Dimension 5: the global actors

The new interactions among global health players is transforming the global playing field in health—its norms, rules, practices and, especially, its power politics.18 The shift from state-centred politics to more complex forms of governance and the increased number of players and collaborative arrangements in global health have led many to believe that there has been a diffusion of power among global health players. This is not necessarily the case. The increased interconnectedness between health and non-health actors is blurring their traditional boundaries,19 and the permeability of national borders has diminished governmental control over a growing number of health determinants.20 At the same time Member States have systematically weakened the remit of their own intergovernmental organization, the World Health Organization.

In consequence, accountability and transparency have emerged as key issues among global health actors. However, few experts have examined its role in health,21 and definitions of accountability are often vague. Actors in the public, business and civil society sectors differ in to whom they are accountable. Indeed globalization may lead to a reduction of accountability.22 Brugha and Zwi, for example, show that accountability was lacking at both national and global levels when the World Bank and USAID pushed for privatization of health care—policy advice that later was regarded as questionable at best.23 Furthermore, lack of transparency in creating policies only worsens the already inadequate accountability of powerful global organizations.24 Negotiations at the WTO on public health issues have not been transparent nor have they included the voice of civil society. Instead they have catered to the interests of industrialized nations' commercial sector. The dispute resolution process, held behind closed doors, has not incorporated the technical expertise of public health experts but instead relied on trade lawyers and diplomats.25 Finally, global health partnerships also face challenges in accountability because the role and responsibilities of each partner are not always clear.

2.4.6. Dimension 6: systems failure

The development agencies and lending institutions have not been willing to support what laid the basis for the health and life expectancy gains in the first and second public health revolutions: a strong state, laws and regulation, public health, public education and the understanding that health is part and parcel of a citizen's right. In the 19th century with the social conflict around health and citizen's rights, a new principle entered health governance: the concept of solidarity as an integrative force for both social movements and for identity and cohesion within the nation state. Public health was understood to be a social enterprise.

This collective and societal orientation of public health has been lost. Yet in the face of globalization Geoffrey Rose's public health dictum is more important than ever: “The primary determinants of disease are mainly economic and social, therefore its remedies must also be economic and social.”26

One element of the systems failure in global health has been the tendency to be wedded to a charity model, which focused on the ‘deserving’ and the ‘undeserving’ poor rather than on citizens rights. ‘Global health means that the health of the poorest and most vulnerable has direct relevance for all populations because of the many interconnectivities that increasingly bring the world closer. From this perspective, the underlying basis of health sector aid should shift from providing charitable handouts to ensuring appropriate and sufficient resources for a global health system that meets the common needs of the human species.’27

2.5. A new conceptual map

Public health is at a crossroads. The changes that societies are facing are as significant as the ones encountered in the ‘golden era’ of public health 150 years ago, and they are truly global in nature. In consequence, a new conceptual map is needed for public health action that incorporates, in new ways, scientific and technological development; political, social and economic action; and domestic and global public health responsibilities. Inge Kaul, in her work on GPGs, emphasizes the need to develop a new global policy model. “The pervasiveness of today's crises suggests that they might all suffer from a common cause, such as a common flaw in policy making, rather than issue specific problems. If so, issue specific responses typical to date, would be insufficient—allowing global crises to persist and even multiply.”28

It was one of the characteristics of modernity to take health out of the confines of religion and charity and make it a key element of state action and the rights of citizenship. This process, initially within the context of the constitution of the nation state, today needs to go global as a key dimension of global justice. The present global drive for access to AIDS medicines for developing nations, for instance, is not just about health. It is the spearhead of a global citizenship movement that has recognized that global health needs to move out of the charity mode into the realm of rights, citizenship and a global contract. The global public health community must reorient and strengthen public health within both developed and developing societies as a joint endeavour, and advocate for a resilient system of global governance for health based on a new global social contract, a point also raised by Richard Smith in a recent BMJ editorial.29

2.6. The third public health revolution is global

The approach to public health must change—it must again become an art and a science, it must be a discipline that is fully engaged in the political and social arena. There is more at stake than just health—because the new interdependence and the new global dynamics have positioned health as a defining characteristic of the global society of the 21st century. The third public health revolution needs to be a global revolution oriented around five principle areas of action.

2.6.1. Health as a global public good

Securing global population health must, first and foremost, be seen as a GPG. GPGs are defined as having non-excludable, non-rival benefits that cut across borders, generations, and populations.30 There is no us and them any more in health. The GPG concept implies that society must ensure the value of health, understand it as a key dimension of global citizenship and keep it high on the global political agenda. It means defining common agendas, increasing the importance of global health treaties and pooling of sovereignty by nation states in the area of health. ‘The GPG perspective demonstrates that today's global health challenges require not just good national policies, but also strong global responses, the focal point thus being international collective action.’31

2.6.2. Health as a key component of global security

Global integration has proven that disease outbreaks are a threat to national, international und human security. Nation states should incorporate health issues into their security and their development strategies. They need to understand that in health domestic and foreign policy increasingly overlap. Global health surveillance and rapid response must be ensured and the WHO will need to extend its global health surveillance role and expand its interventionist power in the context of the International Health Regulations. The WHO member states and the private sector must also comply with international bodies in reporting potential health threats and should support the joint financing of a global surveillance infrastructure. A rapid health response force could be ensured through a new kind of GPGs tax, for example, on airline travel.

2.6.3. Strengthening global health governance for interdependence

Health must not only be viewed through the lens of development but also through the reality of interdependence. WHO must use its existing constitutional capability to ensure agenda coherence in global health and it must strengthen its convening capabilities. It should further develop mechanisms that ensure transparency and accountability in global health governance and play a brokering role in relation to the health impacts of policies of other agencies. WHO must make certain that the new collaborative arrangements in global health evolve into reliable and accountable policy networks of governance.32 Indeed, recognition of the organization's coordination and leadership role should significantly reduce the transaction costs for countries and for donors.

2.6.4. Accepting health as a key factor of sound business practice and social responsibility

Increasingly, sound business practice is being understood in terms of corporate citizenship, which makes companies more accountable for public goods—in particular, those that improve health. Accepting health as a key factor of corporate social responsibility means that businesses must invest in health. Avenues for corporate investment in health can be outlined at four levels: workplace, marketplace, community and policy. Businesses can also form partnerships or become members of business coalitions for health as a strategy to increase corporate citizenship. In addition, businesses can contribute to large funds, such as the Global Fund, and can also work in partnership with development agencies. CEOs can take the lead as key corporate individuals dedicated to certain health issues, such as Bill Gates, George Soros and Ted Turner.

2.6.5. Accept the ethical principle of health as global citizenship

A greater push towards health as global citizenship is essential. Health and globalization is not an afterthought but is at the core of this change. The key aim of the global public health community must be to establish health as a right of global citizens and promote GPGs for health. Together with a strategy of empowerment and community involvement such an approach acts as a spearhead to enable and support health literacy and individual health behaviours and ensures the interface between the local and the global. This means underlining the importance of the state and the public sector; it means translating the do-ability of health into strong public health systems with both a national and a global dimension because they can be separated less and less.

Amartya Sen has always insisted that the understanding of health as an end (the right of citizenship) is as important as the utilitarian principle of health as a means—the global public health community must stand firm on insisting on the interface between the two.

3. Comments on Prof. Kickbusch's Leavell lecture Prof. David Sanders (Head, School of Public Health, University of Western Cape, South Africa)

Professor Ilona Kickbusch delivered a thoughtful and passionate Leavell lecture that succeeded in discomfiting all of us by drawing attention to the stark and increasing inequalities in health between and within countries. She challenged us by insisting that there is no longer US and THEM: she rightly points out that, in the era of globalisation and interdependence, it is only US. (Or does she mean, only the US, as the single, increasingly bullying superpower?) She further challenged the international public health community to demonstrate the do-ability of health through, inter alia, advocacy for global responsibility, increases in overseas development assistance, and development of legal instruments to ensure that ‘global governance’ institutions (e.g. WHO) fulfil their mandate.

Prof. Kickbusch proposes five action areas for ‘the third public health revolution’: health as a GPG; health as a key component of global security; health as a key factor of global governance of interdependence; health as responsible business practice and social responsibility; and health as global citizenship. She urges a move from a charity model to one that recognizes rights of citizenship and to a focus on the political determinants of health and globalisation and avers: “we need to build a global system of responsibility that ensures access to basic health even when states fail”.

Her proposed action areas and call for a shift in focus are both welcome and appropriate. However, what is not clear from her lecture is how this is to happen. She suggests that the resources needed to achieve the MDGs could be secured by obtaining US$100 a year from each middle class citizen in the developed world, thereby implying—like the Sachs Commission on Macroeconomics and Health—the implementation of an aid or ‘charity’ response from the North, one she correctly earlier criticizes as inappropriate in the 21st century. What is missing from her model that aims to strengthen global governance is the means to achieve this. Notwithstanding her references to the ‘harsh political and ideological battles’ which accompanied the first two public health revolutions, or her invoking of the successful push by global social movements in improving access to HIV/AIDS treatment, Prof. Kickbusch is strangely silent in identifying social mobilization as the key factor to render governments—both national and global—accountable and responsive. Here, an explicit identification of the centrality of social struggle in achieving reforms necessary to advance the public's health is needed to enhance the vision she offers us. Further, it would be appropriate here to identify the urgent need for the public health community to proactively assume its historic role of supporting such social struggles through, at a minimum, producing evidence of the negative aspects of globalisation and its effects, and of the positive health impact of equitable policies. In this way, we may contribute to the achievements of the laudable—but receding—goal of responsible and responsive global governance.

4. Comments on Prof. Kickbusch's Leavell lecture Sir Liam Donaldson (Chief Medical Officer, Department of Health, England)

4.1. A new public health paradigm

If the 20th century was one of national health, then the 21st was global health, chief medical officer Sir Liam Donaldson told delegates. This encompassed the effects of continuing globalisation along with health impacts of the foreign policies of countries like the UK he said, echoing Ilona Kickbusch's vision for public health.

There was also a need for a revolutionary reshaping of the educational curricula of health professionals, he said, to give public health a much stronger voice. “At the moment it's a strand in the curriculum, not a shaping force. It's just part of the programme”. This was coupled with a pressing need to look at the infrastructure of public health, he said, as one of the movement's failings had been ‘our inability to get our act together’.

Cross-governmental action was needed, he stressed, and public health practitioners needed to engage more fully with the political process. Philosophies of individual responsibility were a barrier to progress, and avoiding getting tangled up in the negative and perjorative language of ‘nanny state’ was a huge challenge facing the movement.

5. Global public health challenges and the role of primary health care Rafael Bengoa

Abstract

The World Health Organisation recently undertook a global review of Primary Health Care (PHC) covering both PHC as an approach to fulfilling the Health-for-all (HFA) principles outlined in Alma Ata, as well as, Primary Care as a level of care. The review concluded that HFA and PHC are still considered useful policy-making frameworks to meet the public health challenges of this century, especially those related to globalisation, and serve as a necessary complement to meet the MDGs. The prescriptive nature of the HFA and PHC formulations were a product of the planning paradigms of the time. At present they need to be framed as an umbrella strategy, which allows more local learning and flexibility. The need to have a vision such as HFA may prove to be even more important today than before.

5.1. Background

An image is frequently more useful than a long speech. The sand clock, strangled in the middle but widening around two spheres in both extremities has been a useful concept in our minds when thinking about time. The thin passage in the middle through which the sand passes represents the present while the above sphere reflects the past and the lower sphere represents the future. The present only has a thin portion while the past and the future have a bigger representation in our minds.

This representation is no longer valid in a world where the present has taken over and in which individuality has precedence over collective needs. The sand clock has become an egg in which the present is more important than the past and the future. The past no longer has the same strength and the future is downgraded relative to the present. Those who talk about the need for a vision such as HFA or MDGs seem to be quickly dismissed. Those who look back and praise the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 are frequently paralleled with the dinosaurs.

The HFA aspirations and PHC strategic intents have been caught up in the new temporality that the French call ‘le présent permanent’. There are even certain philosophers33 who welcome this victory of the ‘present’ because we should not be trying to change or transform the world into a better place. We should only contemplate it and let some natural balance fix things. In this context it is not surprising to witness a sort of collective amnesia with HFA and PHC. It is interesting to note these growing arguments in favour of some massive ‘laissez faire’ while some of the negative elements of globalization are taking their toll. A quick overview of some of the key trends in the health sector and their impact on populations highlights the continued need for some sort of strategic vision.

5.2. A changing world in the midst of globalization

When Alma-Ata was being formulated in 1978, the speed of globalization and especially its negative impacts were not as well understood and interiorised as today. Likewise the changing role of Governments and their varying roles in health were not as complex as they are today.

5.3. Some key trends in a changing world

-

•

Socio-economic trends such as globalization, industrialization and urbanization are transforming how populations live, our sense of community, and the determinants of individual health. An example is the process used and the extent of how risk factors are being transmitted by globalization as expressed in Fig. 1 .

The general flow of risk factors is from developed to less developed economies.

Foreign Direct Investment by global corporations has risen exponentially in the past 25 years since Alma-Ata (1978), again towards less developed nations. The large transnational corporations are now 65,000 with 850,000 foreign affiliates. This may mean improved economic growth in some nations but the trend also carries with it the risk factors, which provoke cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes.

-

•

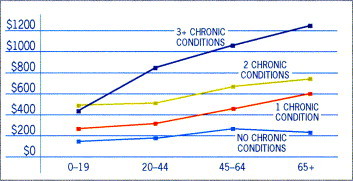

Given the above transfer of risk factors, health status continue to change rapidly, with chronic noncommunicable diseases reaching epidemic proportions in developed and developing countries, and chronic conditions now presenting challenges for which most health systems are ill-equipped. Most people have more than one chronic condition. Fifteen percent of a population can have up to five chronic conditions. Seventy-eight percent of medical care spending in developed nations is by people with one or more chronic condition, and 60% of medical care spending is by people with multiple chronic conditions. Given the present trends with chronic conditions less developed nations will soon find themselves in a similar situation. Fig. 2 indicates how out of pocket spending increases with multiple chronic conditions in one developed nation (USA).

-

•

The war against communicable diseases has not been won, old enemies such as tuberculosis and malaria are gaining some ground, new diseases such as SARS bring new challenges, and HIV/AIDS is having a devastating effect in many countries (especially in Sub-Saharan Africa). In the year 2001, HIV/AIDS was responsible for 5.1% of all deaths around the world.34 At present, 40 million people in the world are infected with HIV and 6 million are in immediate need of AIDS treatment. Between 2000 and 2010, the burden of disease from HIV/AIDS is projected to increase by nearly 20%, before declining in the next decade.

-

•

Population demographics continue to present new scenarios, with substantial increases in birth rates in some countries, declines in others, a much larger world population of the elderly and dramatic changes in life expectancy in the countries most affected by HIV/AIDS.

This widespread ageing of populations is both one of humanity's greatest triumphs, and one of its greatest challenges.35 Whilst older people are a precious resource who make an important contribution to the fabric of our societies, they make considerable demands on health and social care systems. Worldwide, between 1970 and 2025, the number of older people is expected to increase by 223%.

-

•

Member State governments continue to rethink their roles and responsibilities in relation to population health and the organisation and delivery of health care, thus changing the context for health policy development and implementation locally, nationally and internationally.

Figure 1.

Trade of Cigarettes inside and outside the United States.

Figure 2.

Out of Pocket Spending Increases with Number of Chronic Illnesses.

In practice, whilst governments continue to accept a central role in policy making in health, the instruments available to support policy implementation may now be much more wide ranging. Those instruments will depend on whether governments have developed roles which include some or all of:

-

•

Funders of health systems

-

•

Providers of health care

-

•

Commissioners of health care

-

•

Regulators/accreditors of health systems and health care providers

It is therefore necessary to face a combination of a fast changing policy environment, fast changing burden of disease mainly driven by globalization and a shift in government roles in health. It is reasonable to believe that some broad organized strategy is required in order to meet these challenges. It is also obvious that the strategy will have to be comprehensive and cover interventions which span across a continuum of both international and national regulations, upstream health promotion and disease prevention interventions and new financial and organisational arrangements in health care.

5.4. Are HFA and PHC still useful frameworks in this context?

Given the above description of the worsening trends and the impact of globalization on the health of populations since Alma-Ata, one could be sceptical that the aspirations and principles incorporated in that public health movement have had any impact or could continue having one.

Interestingly the world has not only moved on in relation to the challenges and the complexity faced by the public health community but also with the solutions. Many of these solutions were not present 25 years ago indicating that the main difference with the period of Alma-Ata (1978) is that today we have further indication of how to progress with that ambitious agenda. Furthermore many of those ‘hows’ cover the comprehensive spectrum ranging from upstream regulation, population health promotion interventions and more downstream reorganisation of services related to individual health. The instrumental value of using those frameworks in policy-making has been confirmed in the global review of PHC undertaken by WHO in the past 2 years.36 In other words, many of those solutions have arisen because there was a HFA and PHC framework serving as a guide. This gives reasons for optimism and confirms the need to continue having a vision to drive improvement.

The WHO review of PHC indicates that, if anything, the above mentioned changing world situation requires stronger commitment to equity in health, stronger community participation with an active consumer in health and not a mere spectator. It calls for a participative patient in health care, requires even more intersectoral work than 25 years ago, and it consequently requires Governments to continue having a key role in the governance of health. From that review, four main directions of work with specific interest to the public health community are highlighted here.

5.4.1. Learning how to orient ‘illness systems’ towards a broader health agenda

Many developed countries are still trying today to ensure their ‘illness systems’ take a broader public health perspective and are seeking organisational and financial models that will orient their health systems in that direction. This move implies connecting the formal illness system to the broader health agenda. This is not new as a concept; what is new is the progress made in achieving it as well as the decentralised approach being followed as it is expected that the illness system connects with the community population components at the local level.

Many countries use the HFA and PHC frameworks for that shift. Most countries recognize in their new policy formulations that they inform their analysis using the HFA and PHC principles.

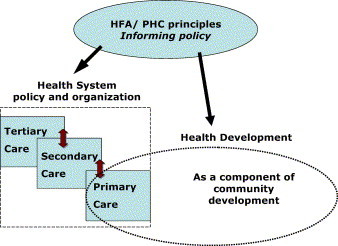

The relationship between the guiding principles of PHC, the development of health systems and the development of health as a component of community development, is summarized in Fig. 3 .

Figure 3.

It is interesting to note that those countries who are tying up the broader population and community development agenda with the more traditional illness system are precisely establishing the link at the level of primary care. The past years since Alma-Ata have witnessed the difficulties that health systems, even in developed nations, can have in addressing broader health goals and health inequalities. The above trend aims to correct this by structural efforts to strengthen the public health function in local PHC settings. The intention is to improve local public health surveillance, reinforce health promotion and disease prevention interventions, and activate a local health inequalities agenda. This trend involves existing public health specialists working more closely with the local PHC team and local communities. The intention of these innovations is to complement the dominating clinical approach with population-based approaches.

5.4.2. Learning how to implement intersectoral action

Globalization requires new approaches to address a range of problems that cross national boundaries and provide a rationale for the implementation of global norms to deal with shared problems. As indicated above, the new challenges in public health require a comprehensive response and that response may have to be regulatory in character in some circumstances. This concept is not new and that is why intersectoral interventions were given such high profile in the PHC principles in Alma-Ata. What is new is that the international community now knows how to engage in some of these issues.37 For example, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control approved by member states at the World Health Assembly in 2003 and presently being ratified by countries provides invigorated direction to enhance preventive and promotive strategies through the application of legal instruments to international health issues.

Furthermore international attitudes to the reduction of poverty and the improvement of health for the world's most disadvantaged populations are also changing. This intersectoral effort is well illustrated by the recommendations of the WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health.38

In its report, the Commission challenges traditional assumptions that the health of the world's poor will improve as a result of broader economic development. Its central proposal is that the world's low and middle income countries, working in partnership with high-income countries, need to significantly scale up the access of the world's poor to essential health services, if the MDGs adopted by the United Nations in September 2000 are to be met. It is unrealistic to expect the achievement of the MDGs (reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases), without organized PHC.

Interestingly the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health also argues that the most effective interventions can be delivered through health centres and similar facilities, and through outreach, which they collectively describe as ‘close to client’ systems. This is an obvious endorsement of both the principles and the best practices of PHC.

5.4.3. Learning how to change health systems

Changes to the health system itself will be required to complement the broader intersectoral interventions. Thus the challenges described above will require significant shifts also in the financing and organisation of health services.

This is especially important in relation to the rising challenges of both communicable (HIV/AIDS) and non-communicable conditions such as diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, arthritis, depression and hypertension. These are all chronic conditions and as such require ongoing life long care. In general the health care systems of today are not oriented to this type of care and continue to be focussed on providing acute and episodic care.

It is important for developing nations not to find themselves in the same situation as developed nations in relation to the fragmentation of the financing and delivery of care. Adjusting the system of financing and delivering care to better attend the needs of people with chronic conditions requires a focus on preventing diseases which should have a high appeal among public health practitioners. The lack of such an approach may lead to inappropriate or unnecessary service utilisation further increasing health spending.

It has been known for a long time that health services deliver fragmented care and that it was necessary to integrate. What is new today is the existence of models to organize more integrated approaches and responses to those chronic needs. They imply a redesign of primary care and community services. These models construct integrated care led by primary care, and practice continuous care as well as improving the connection of formal health services with the community.

Furthermore what is new is that different chronic diseases have common problems and therefore share the same solutions. Chronic disease management can become the management of one disease after another in the same way as communicable diseases have been organized in silos, one by one leading to excessive vertical programmes. This can be avoided in chronic disease by focusing not on the management of each disease separately by each medical specialty, but rather by focussing on the synergies provided by the same solutions. For example, they all require a strengthened approach to self-management as a shared solution for all. The emergent models of care for chronic conditions build on the need to avoid a silo approach to managing diseases.

5.4.4. Learning how to learn

All of these complex social and economic challenges facing health systems combine to create a wider environment in which health policy development and health services delivery has to assume that:

-

•

change will happen fast

-

•

there are few certainties

-

•

today's priorities may not be tomorrow's priorities

-

•

today's solutions may not work tomorrow

-

•

we cannot know in advance all of the problems we will face

-

•

new opportunities will arise from developments such as the growth in partnership working.

What is new is that this type of environment requires a more flexible approach to policy making; one in which a learning approach is more relevant, one which allows emergent patterns to change the strategy as one implements and learns from it. This was not the approach that was assumed during the formulation of HFA and PHC principles in 1978 in which the environment was considered relatively stable and more predictable than today. It was reasonable then for a strategy such as HFA/PHC to be more prescriptive and rational. It was an expression of the rational planning era of their time, a time in which strategies were formulated and someone had to implement them; a time in which there was no feedback loop to strategic policy‐making.

It is interesting to note that today, as countries are using the HFA and PHC strategies as umbrella strategies, they are developed allowing for continuous adjustment to be made as learning takes place at the local level all within the logic of experimentation and growing local control.

5.5. Looking back and looking forward

Henry Mintzberg has recently said that “ignorance of an organisation's past can undermine the development of strategies for its future. We ignore the past at our own peril.”

Let the reader decide whether the following text is still relevant for the challenges of today.

The Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 set out for the first time the principles of Primary Health Care. These principles have provided the basis for Member States and international agencies taking forward their programmes for improving population health over the last quarter of a century.

The declaration proposed that Primary Health Care should:

-

•

“Reflect and evolve from the economic conditions and socio-cultural and political characteristics of the country and its communities and be based on the application of the relevant results of social, biomedical and health service research and public health experience”

-

•

“Involve, in addition to the health sector, all related sectors and aspects of national and community development, in particular agriculture, animal husbandry, food, industry, education, housing, public works, communications and other sectors; and demands the co-ordinated efforts of all these sectors

-

•

“Promote maximum community and individual self-reliance and participation in the planning, organisation, operation and control of primary healthcare, making fullest use of local, national and other available resources and to this end develop through appropriate education the ability of communities to participate”

-

•

“Address the main health problems in the community, providing promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative services accordingly”

-

•

“Be sustained by integrated, functional and mutually supportive referral systems, leading to the progressive improvement of comprehensive health care for all and giving priority to those most in need”

-

•

“Rely, at local and referral levels, on health workers, including physicians, nurses, midwives, auxiliaries and community workers as applicable, as well as traditional practitioners as needed, suitably trained socially and technically to work as a health team and to respond to the expressed health needs of the community”.

6. Focusing on the poor world The Right Honourable Mr Hilary Benn MP

My perspective is that of the public health priorities facing the poorest countries:

-

•

where 1.2 billion people live on less than one dollar a day

-

•

where governments spend perhaps 3–5 pounds annually on health services

-

•

where the priorities still remain the major communicable diseases

-

•

where ensuring access to basic preventive and curative care remains a challenge and where governments have limited financial space to act

-

•

where HIV/AIDS is undermining the development gains of the past 30 years

-

•

where 500 million people live in failing states or are affected by conflict and where any functioning health service may well have dissolved.

In such settings governments have barely begun to address the hidden or emerging epidemics—the non-communicable diseases, traffic accidents, mental health, or the impact of tobacco.

I would like to touch upon some of the areas that you will be discussing over the next few days. The subject of the meeting, sustaining public health in a changing world: from vision to action, is particularly appropriate.

Let me start with the vision.

Over the past 30 years the international community has articulated a number of visions of better public health. Health for all by 2000; Primary Health Care; Universal Child Immunisation; goals to eradicate diseases such as smallpox, polio and malaria. More recently the World Health Organisation, in response to the global crisis of HIV/AIDS, has issued a call to provide antiretroviral treatment for three million people with AIDS by the end of 2005.

Undoubtedly the most important vision for the decade ahead is reflected in the MDGs, an ambitious set of broad development targets to be achieved by 2015. These emerged from a series of the high-level development conferences of the 1990s. One hundred and forty-seven heads of state endorsed the distilled set of eight goals at the millennium summit in September 2000.

The Millennium Goals provide a framework for action for governments and development agencies. They are at the core of the work of the UK Department for International Development. They provide ambitious but achievable targets for 2015 and have now been endorsed by 189 countries. They are considered technically achievable and affordable.

They are a means to an end; to a better life for people. Many of the goals are specific to health; reducing child mortality by two thirds; reducing maternal mortality by three quarters; reversing the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Achievement of other goals will also impact upon the health of the population; halving extreme poverty and hunger; achieving universal primary education; promoting gender equality; and ensuring environmental sustainability.

So the vision is clear but what about translating that vision into action?

Too often past commitments have not been translated into effective action on the necessary scale. We have achieved commendable success in a number of areas. Smallpox has been eradicated; polio will soon follow; very high levels of child immunisation were achieved by 1990; we have seen massive increases in use of modern forms of contraception-providing the choice that women want.

In other areas we have failed. Controlling malaria was perhaps one of the most notable examples. Despite a promising start in the 1980s we have failed in much of the world to sustain reductions in child mortality. In many countries levels of maternal mortality remain those of 19th century Europe.

We have failed to provide access to the range of effective, and often low cost, preventive and curative interventions that target the major causes of the burden of disease. The HIV/AIDS pandemic, the resurgence of TB and malaria and the broken down state of health services in many countries have slowed down, and in some cases reversed progress.

This failure is not due to a lack of science or technology. Progress does not require new technologies. That said, my wish list to those in the audience from the research and technology communities would include effective vaccines against HIV, TB and malaria and a microbide that would do so much to empower women in efforts to prevent HIV infection.

Effective interventions exist but are too little used. The World Bank estimates that ensuring almost universal access to available, proven preventive and curative interventions could reduce under-five mortality by more than 60% and maternal mortality by almost three quarters. Greater access to effective treatment for malaria; use of insecticide treated bed nets for the vulnerable; measures to reduce smoke in the home; clean water and sanitation; immunisation; access to essential obstetric care. These should be part of the ‘essential health package’ that should form the core of any health service. Many can be delivered through interventions in the home, in the community and in lower levels health facilities. The opportunities remain massively under-exploited.

Some regard the MDGs as over ambitious and yet another vision that will be forgotten. Clearly there is a mixed half time score. While there been good progress on reducing malnutrition there has been slow progress on reducing child and maternal mortality. While many countries will achieve some of the targets we are not moving fast enough. As things stand we will not achieve the MDGs particularly in Africa where in many countries we are going backwards. We should regard this as unacceptable and it should shame the world.

One of the conference sessions asks the question—Have public health professionals lost much of their leadership role and is public health in crisis?

I would reject such views. It may be a different public health in a global setting but there are clear indications of the impact of the advocates and professionals in the public health community.

Health has a greater international profile than ever before. Health, particularly the impact of HIV/AIDS, is now debated at the level of the United Nations Security Council. It appears on the agenda of high-level political fora such as the G8. It is a key element of the New Partnership for African Development. It plays a prominent part in EU agendas. There is a serious commitment within the UN agencies to deliver against the MDGs.

Health is increasingly reflected in national plans to reduce poverty and the strong relationship between efforts to improve health and poverty reduction is widely accepted. Health has moved beyond the Ministry of Health and is increasingly on the agendas of Ministries of Planning and Finance in low-income countries.

Resources for health are increasing although to reach the levels of development assistance of the 1980s will require some catch up. A new instrument, the Global Fund to fight HIV/AIDS, TB and Malaria is now getting off the ground and promises to deliver significant increases to help country efforts to reduce the impact of these diseases. The UK Chancellor has proposed a doubling of aid—in effect providing an additional US$ 50 billion annually through a new instrument, the International Financing Facility.

Ministries of Health are getting better at demonstrating the effectiveness of aid and donors are getting better at working together in support of country plans and priorities. With leadership, the right policies and practice poor countries can make rapid progress. Last week in Uganda I saw evidence of a doubling of the numbers using health centres, large rises in immunisation coverage, more money being spent on essential drugs and commodities, and more health workers in post. Effective early leadership on HIV has led to a reversal of the epidemic.

New health partnerships continue to emerge, often to deal with specific issues, most notably the major communicable diseases; malaria, TB and HIV/AIDS. The Stop TB Partnership and Roll Back Malaria, have set clear agendas for global action. More mature partnerships have delivered real success in reducing the impact of river blindness and guinea worm in Africa and in driving forward polio eradication.

We need to scale up our response. More aid is part of the picture but needs to be allied to more effective institutions, leadership and good governance. It is not solely a lack of finance. It is true that many of the poorest country governments only spend a few pounds per capita on health each year. Yet it is tragic to see administrations fail to use available funds to the full and to best effect. Debt relief for the poorest countries, progress on a fair trading systems and resolution of conflict all will play important parts in the overall response.

Finally let me look to the immediate future.

2005 will be an important year. The UN Secretary General will lead a major stock take of where we are on the path to realize the MDGs, where the bottlenecks lie and where there are opportunities to accelerate progress. A High Level Forum has been established across governments and development agencies to identify constraints and propose effective action. The human resource crisis facing developing countries will be an early focus.

A special effort is needed on Africa, The continent has grown poorer over the past 25 years. My Prime Minister has recently established a Commission for Africa to take a fresh look at the continent—at what has worked; what has failed and where more support is needed. Health and HIV/AIDS will be key themes of the work which will influence the future UK agenda, notably the UK Presidencies of the European Union and the G8 in 2005.

I believe that we are at a critical point in our efforts to improve global public health. The profile is high, the relation between ill health and poverty is clear. Health is moving beyond the concern of under-resourced and stretched Ministries of Health. Resources are increasing although not at the rate that we would wish. New partnerships are providing a new impetus to our efforts.

We cannot continue to live side by side with poverty and disease. Many of the problems of the Africa and Asia today already impact on Europe. HIV and TB rates are rapidly increasing in the UK. With the accession of new EU states the borders of Europe will be adjacent to the fastest growing HIV epidemic in the world—in the former Soviet Union. The most effective way to reduce the impact is to reduce poverty in poor countries and invest in strengthening health systems in those countries.

The MDGs provide the framework; we have the tools to hand. It is now down to scaling up our collective response.

7. Financing global public health: innovation and investment Richard Feachem

Around the world, health has improved greatly over the past half century and most aspects of human health continue to improve. There are five notable exceptions to this positive trend. Two are chronic: namely everything to do with tobacco abuse and everything to do with obesity. The other three are the great infectious pandemics of our time; HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. In this talk, I will focus on the three great uncontrolled pandemics—AIDS, TB and malaria. Each of these infectious diseases is worsening and spreading in most parts of the world. Current efforts are not, and have not, made much of a difference.

One of the three pandemics is in a class on its own. HIV/AIDS is the greatest disaster in recorded human history. It is already worse than the black death in Europe in the middle of the 14th century, and the word ‘already’ is important because the epidemic will get far worse before it gets better, even if we did all the right things tomorrow. There is no chance that we will do all the right things tomorrow.

HIV/AIDS is bringing countries in Southern Africa to their knees. Three African Heads of State have predicted that their countries may cease to exist as organized nation states if current trends continue. HIV/AIDS in Zambia is killing school teachers at twice the rate that school teachers are being trained. And the worst is still ahead of us.

Meanwhile, the epicentre of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is shifting to Asia. India today already has the largest number of infected people (notwithstanding official statistics). There is nothing going on in India today, which has a serious chance of attenuating what will otherwise be a devastatingly large epidemic. While we meet here in Brighton, the newspapers are full of the Indian general elections. A triumph for democracy on a grand scale. India will be a much poorer and sadder place at the time of its next general election unless we mount a massive and effective effort in HIV prevention very quickly.

But we now have optimism and hope. These are based on the fact that the three preconditions for a successful counterattack, especially against HIV/AIDS, are now sufficiently in place. The first precondition is leadership. Leadership in the North and leadership in the South, leadership from presidents and prime ministers, leadership from bishops and cardinals, leadership from captains of industry, leadership from civil society. We need more of this, but we already have sufficient leadership to really begin to make a difference.

The second precondition is affordable and practical technologies. The most dramatic example of the new availability of such technologies is in the field of antiretroviral therapy. Four years ago such therapy might cost over $20, 000 per year and might involve taking between 20 and 30 pills per day. Now it costs under $200 per year and involves taking one kind of pill, twice per day. This is a revolution in technology, the like of which we have never before experienced.

The third precondition is new money and new investment, on a large scale. In 1993, the World Bank devoted, for the first time, its World Development Report to the subject of health. In this report, the case was made that health spending, if wisely done, is an investment in human capital and in economic growth and prosperity for the future. The Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, reporting in 2002, strengthened this argument. But the Commission also made the point that you cannot run a health system on $10 per capita per year, and you cannot run it on $11 either. The Commission estimated that it takes about $40 per capita per year to run a basic health care system—a two-, three- or four-fold increase for many countries, but still less than 1% of national per capita expenditure per year on health in the USA. The Commission called for massive new investments of foreign assistance in health. The skeptics said ‘dream on’.

Well some of us dreamt! Only 2 years later we have a Global Fund. It has assets already of $5.4 billion. It is already supporting 225 programs in 121 countries. It is run by a small team of 80 people in a single office in Geneva. It is an independent private foundation with a core business model that is unlike any other development finance agency. Sixty percent of our money is going to Africa and 40% to everywhere else. Sixty percent of our money is going to AIDS, 20% to TB and 20% to malaria. Fifty percent of our money is going to private and non-governmental recipients while the rest goes to support government programs. These distributions are interesting because we have no policy on any of them. Our portfolio is entirely demand driven. I am not sure whether Adam Smith's invisible hand is at work, or someone else's, but it is fascinating to see how the entirely demand driven processes of the Global Fund lead to distributions in our portfolio which most observers would think are about right and in the global interest.

But we urgently need a lot more money. Income needed for 2004 is $1.6 billion. Income needed for 2005 is a whopping $3.6 billion. We are climbing rapidly to a cruising altitude of $7–8 billion per year by 2008.

Some people say that these numbers are too large and are over ambitious. One has to ask too large compared to what? Too large compared to the $70–80 billion to be spent this year in Iraq and Afghanistan? Too large in relation to the $350 billion that the EC and the USA spend in subsidizing their farmers in order that they can compete unfairly with the farmers of the developing world? Too much in relation to the $1, 500 billion ($1.5 trillion) that those who live in the USA (including me) will spend on their own health in 2004? Too large compared to the devastation, suffering and economic decline that AIDS is causing? I do not think so! And remember, that the longer we wait, the more expensive and more difficult the counter measures will become.

But we need your help to move the $1.6 billion in 2004 to $3.6 billion in 2005 and to continue the climb to $8 billion per year by 2008. This requires three things to happen, and your engagement is critical to the achievement of all of them. First, we need further generosity from the UK government, perhaps to a level, which will match the support that we receive from France. Second, we need support to Tony Blair during the UK Presidency of the European Union in the last half of 2005 to ensure greater use of the European Development Fund for the purpose of financing the Global Fund. Third, we need your support to Gordon Brown and Tony Blair during the UK Presidency of the G8 in 2004 to successfully launch the International Finance Facility and thereby make large additional funding available to the Global Fund, to GAVI, to the water initiative, to the programs to accelerate education for girls and for the other MDGs and great GPGs of our time.

In achieving all of this, your voices matter. Please raise them!

8. The road from health to wealth David Byrne

People in the European Union are living longer and are in better health than ever before. This is of course good news. Nevertheless we have important challenges to address.