Highlights

-

•

The nucleotide variations among the N genes of 13 different coronaviruses (CoVs) were interpreted.

-

•

Overall, 18 amino acids observed with varying preferred codons.

-

•

The effective number of codon values ranged from 40.43 to 53.85, revealing a slight codon bias.

-

•

A highly significant correlation between GC3s and ENc values was observed in porcine epidemic diarrhea CoV, followed by Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Nucleocapsid protein, Preferred nucleotides, Amino acid, Codon bias

Graphical abstract

Abstract

The nucleocapsid (N) protein of a coronavirus plays a crucial role in virus assembly and in its RNA transcription. It is important to characterize a virus at the nucleotide level to discover the virus’s genomic sequence variations and similarities relative to other viruses that could have an impact on the functions of its genes and proteins. This entails a comprehensive and comparative analysis of the viral genomes of interest for preferred nucleotides, codon bias, nucleotide changes at the 3rd position (NT3s), synonymous codon usage and relative synonymous codon usage. In this study, the variations in the N proteins among 13 different coronaviruses (CoVs) were analysed at the nucleotide and amino acid levels in an attempt to reveal how these viruses adapt to their hosts relative to their preferred codon usage in the N genes. The results revealed that, overall, eighteen amino acids had different preferred codons and eight of these were over-biased. The N genes had a higher AT% over GC% and the values of their effective number of codons ranged from 40.43 to 53.85, indicating a slight codon bias. Neutrality plots and correlation analyses showed a very high level of GC3s/GC correlation in porcine epidemic diarrhea CoV (pedCoV), followed by Middle East respiratory syndrome-CoV (MERS CoV), porcine delta CoV (dCoV), bat CoV (bCoV) and feline CoV (fCoV) with r values 0.81, 0.68, -0.47, 0.98 and 0.58, respectively. These data implied a high rate of evolution of the CoV genomes and a strong influence of mutation on evolutionary selection in the CoV N genes. This type of genetic analysis would be useful for evaluating a virus’s host adaptation, evolution and is thus of value to vaccine design strategies.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses containing a genome of ∼30 kb and four structural proteins, namely, spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N) (Siddell et al., 2005). The S protein regulates virus attachment to the receptor of the target host cell (Cavanagh, 1995); the E protein functions to assemble the virions and acts as an ion channel (Ruch and Machamer, 2012); the M protein, along with the E protein, plays a role in virus assembly and is involved in biosynthesis of new virus particles (Neuman et al., 2011); and the N protein forms the ribonucleoprotein complex with the virus RNA (Risco et al., 1996). The N protein is a multifunctional structural protein with distinct characteristics like enhancing transcription of the virus genome, associating with other proteins (M protein) during virion assembly, and inducing toxicity to the host cell by disrupting various cell activities (Berry et al., 2012; McBride et al., 2014). The N protein is the most conserved and stable protein among the CoV structural proteins; whereas, the S protein undergoes several drastic changes during virus infection. For instance, its large parts are cleaved during infection by cellular proteases and expose the receptors to activate viral attachment to the host (Fiscus, 1987; Wu et al., 2004a, 2004b; Maache et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2013). Additionally, the S protein is prone to mutations, especially in the amino acids associated with the spike protein-cell receptor interface, in order to overcome host immunity (Wu and Yan, 2005; Sui et al., 2014). In an interesting study, the N gene of the CoV was found to be more effective for evaluating the codon usage bias than the S gene (Ahn et al., 2009). Studies reported that the N protein produced from prokaryotes has been used to generate specific antibodies against various animal coronaviruses including SARS (Loa et al., 2004; Timani et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004a, 2004b; Blanchard et al., 2011). The recombinant antigenic N protein from hCoV OC43 used against the rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for hCoV OC43 and did not crossreact with other coronaviruses (SARS CoV and hCoV 229E) (Liang et al., 2013). Moreover, it was tested in different aged human serum samples and exhibited strong reactivity due to the effective central portion (174–300 amino acids) of the N protein followed by C (301–448) & N (1–173) terminal portions (Lee et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2013). Hence the N protein functions as a sensitive and specific diagnostic tool for hCoV OC43 (Di et al., 2005; He et al., 2005) and it has been further useful in the detection of SARS CoV infection (after the first day of infection) (Che et al., 2004). A similar study on SARS CoV N protein reported immunodominant regions N1 (1–422 amino acids) and N3 (110–422 amino acids) produced specific antigens in BALB/C mice and it reacted with the serum of SARS patients hence it can be used as effective SARS DNA vaccine (Dutta et al., 2008). The N protein of CoV expressed in recombinant raccoon poxvirus revealed an efficient vaccine against feline infectious peritonitis virus infection when administered subcutaneously (Wasmoen et al., 1995).

It is essential to investigate viral gene structures and compositions at the codon or nucleotide level to disclose the mechanisms of virus-host relationships and virus evolution (Bahir et al., 2009; van Hemert et al., 2016). There are 20 amino acids encoded by 61 codons which means that an amino acid could be coded by more than one codon. These alternative codons, up to 6 codons per amino acid, are known as synonymous codons (Nakamura et al., 2000). During gene to protein translation process, some synonymous codons are preferred over others. This is known as codon bias or codon usage bias. Viral genes and genomes exhibit varying numbers of synonymous codons depending on the host (Lloyd and Sharp, 1992). Additionally, codon usage in a virus is influenced by selection pressure and compositional constraints determined by the virus-host system (Karniychuk, 2016). Selective forces act on the gene sequences which maintain the codon bias and gene evolution (Ikemura, 1985; Sharp and Li, 1987; Sharp et al., 1993). Codon bias helpful in the analyzing the horizontal gene transfer as the key evolutionary force to study the molecular evolution of the genes (Doolittle, 1998; Ochman et al., 2000; Woese, 2002). Codon bias occurs during protein expression and it will be same in an organism’s genes when there is a similar tRNA content (Kanaya et al., 2001) Codon bias influences the function of the protein and its translation efficiency (Chaney and Clark, 2015; Supek, 2016).

The aim of this study was to carry out a comprehensive analysis of various characteristics, of the N genes of 13 different CoVs, including preferred nucleotides, preferred codons, codon bias, and preferred synonymous codon usage, and to provide an understanding of the codon patterns of these viruses in relation to their hosts and genome evolution.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Gene data collection and analytical programs

The N genes of 13 different CoV species, viz., Porcine epidemic diarrhea CoV (pedCoV) (171), Middle East respiratory syndrome-CoV (MERS CoV) (265), Infectious bronchitis CoV (ibCoV) (279), Camel alpha CoV (cCoV) (31), Porcine delta CoV (dCoV) (74), Transmissible gastroenteritis CoV (tgCoV) (69), Human CoV 229E (hCoV 229E) (34), Bovine CoV (bvCoV) (49), Bat CoV (bCoV) (34), Human CoV HKU1 (hCoV HKU1) (36), Canine CoV (caCoV) (40), Feline CoV (fCoV) (40) and Human CoV OC43 (hCoV OC43) (112) were used in this study. The coding sequences of the N genes along with their accession numbers were obtained from the GenBank database (Supplementary file). CLC Genomics Workbench 12.0 (QIAGEN, Aarhus, Denmark) (2019) (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/) was used to quantify the nucleotide compositions, A + T % and G + C %. The patterns of codon usage and multivariate statistics were assessed using CodonW 1.4.2 (http://codonw.sourceforge.net//), (Peden, 2000) and the GraphPad prism software was used for correlation analysis.

2.2. Codon usage characterisation

The following parameters of the N gene of each of the CoVs were evaluated to determine the codon bias: the percentage and frequency of each of the four nucleotide bases (A, T, G and C), the G + C base incidences at the starting (GC1) and ending nucleotides (GC3) of the codons, and the number of synonymous codons for each amino acid together with the frequencies of each nucleotide at the 3rd position (A3s, G3s, T3s and C3s).

2.3. Relative synonymous codons usage (RSCU) analysis

RSCU computes the ratios of the expected frequencies of synonymous codon usage by the amino acids against their observed frequencies, assuming that a particular amino acid’s synonymous codons were utilized equitably. A value of 1 for a codon in the RSCU table means that the observed frequency of codon usage by the amino acid is equivalent to that of the predictable frequency, or indicating no codon usage bias; whereas, RSCU values of <1 and >1 indicate negative and positive codon usage biases, respectively. The formula used to calculate RSCU (Behura and Severson, 2013) is:

where Xij denotes an amino acid’s observed number of codons used and ni stands for the amino acid’s overall sum of synonymous codons.

2.4. Analysis of relative dinucleotide frequencies

In a gene, the relative dinucleotide frequencies are determined by calculating the ratios of observed to estimated frequencies of the dinucleotides to determine the codon bias. The formula for the calculating the relative frequency of dinucleotides is:

| (O/E) XpY = [f (XY)/f (X)f (Y)] |

where f(X) and f(Y) are the single nucleotide frequencies and f(XY) stands for the observed frequency of dinucleotides.

Relative dinucleotide frequency values of <0.78 denote under-representation of the dinucleotide usage and values of >1.23 indicate over-representation (Chen and Chen, 2014a). The mentioned values represent the relative abundance of dinucleotides compared to a random distribution.

2.5. Determination of effective number of codons (ENc)

Codon usage bias in a gene can be effectively measured by determining the ENc. ENc values range from 20-61. Higher ENc values indicate low codon bias in which more synonymous codons are used for the amino acids, while lower ENc values represent high codon bias with low numbers of synonymous codons used for the amino acids. Generally, a gene with a strong codon usage bias has an ENc value of 35 or less.

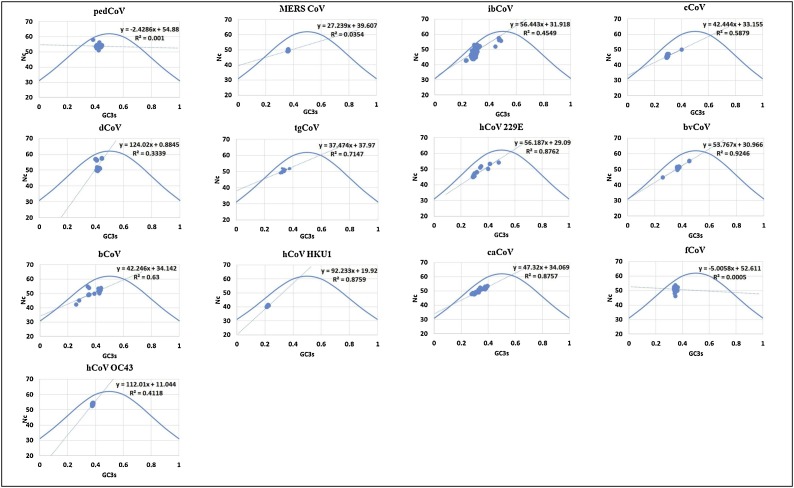

2.6. Assessment of the effect of mutational pressure on codon usage bias

The codon usage bias pattern was analyzed to assess the effective mutational pressure using the ENc plot, in which the GC3 incidence values were plotted against the ENc values (Jenkins and Holmes, 2003; Chen et al., 2004). In ENc plot, the dots represent the individual genes which lie below the curve of expected values subject to mutation pressure. ENc values were interrelated with the mutational pressure which are spread along with the standard curve of GC3 – ENc relation (Fig. 1 ) (Jenkins and Holmes, 2003; Shi et al., 2016).

Fig. 1.

ENc Plots of N genes from 13 different CoVs representing the relation between GC3s and Nc frequencies.

GC nucleotide frequencies at third positions (GC3s) plotted against the effective number of codons (Nc). GC3s and Nc regression is denoted by a linear dotted line and the solid line represents the relation between GC3s and Nc

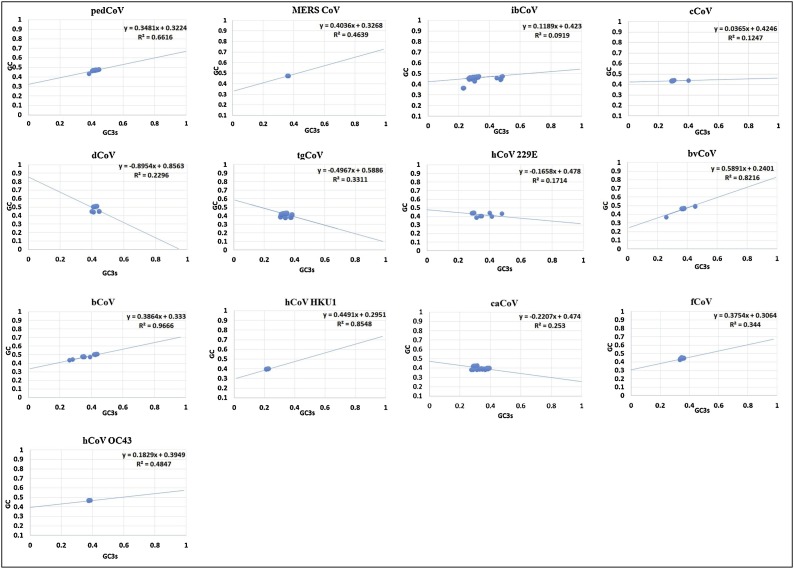

2.7. Assessment of the influence of natural-selection on codon usage bias

Neutrality plot analysis was used to evaluate the bias of codon usage as it influenced by natural-selection, the codon adaptation index, and the indices of aromaticity (AROMO) and hydropathicity (GRAVY) (Kumar et al., 2016). It was plotted with GC1, GC2 against GC3. It estimates the neutrality effect of directional mutation pressure in contrast to selection (Sueoka, 1988). The three nucleotide positions of a codon GC1, GC2 and GC3 are the observed GC contents and mostly the GC3 position has the equal number of A/T and G/C nucleotides. There will be variation between GC1, GC2 against GC3 regression values due to directional mutational pressure.

2.8. Multivariate or correspondence analysis (COA)

COA represents the data geometrically by using RSCU values of the genes (Greenacre, 1984). COA was performed on the N genes of the CoVs, using the CodonW analytical program to analyze the RSCU values and to compare the intragene variations of codon usage in the amino acids (Fellenberg et al., 2001; Perrière and Thioulouse, 2002). Each gene displayed as a 59-dimensional vector (59 synonymous codons represented excluding three stop codons, as well as UGG and AUG encoded by single codon) geometrically shows every codon over 59 orthogonal axes and the variation is projected by the axes (Suzuki et al., 2008; D’Andrea et al., 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Nucleotide compositions of the CoV N genes

Comparative analysis and nucleotide compositions of the N genes of 13 different CoVs revealed the nucleotide A (29.61 %) was the most frequent base and the nucleotide frequencies were A > T>G > C (Table 1 ). Hence, the viruses used more AT% over GC%. Regardless of nucleotide similarities among the CoVs N genes, the nucleotides at the third position (NT3s) of a codon were observed to have variations which contribute to the codon bias and codon pattern differences. The overall NT3s frequencies were T3s > A3s > C3s > G3s. However, it showed some variations when observed individually by summing the NT3s of each gene in the following order of virus (Table 1): tgCoV, fCoV > pedCoV, caCoV > cCoV, hCoV 229E > ibCoV, bvCoV, hCoV HKU1, hCoV OC43 > MERS CoV, dCoV, bCoV. In NT3s, the T3s nucleotide was the most recurrent one with a frequency of 0.62 and the least recurrent was G3s with a frequency of 0.12 (hCoV HKU1) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nucleotides composition of N gene of 13 CoVs.

| Frequencies of nucleotides | pedCoV | MERS CoV | ibCoV | cCoV | dCoV | tgCoV | hCoV 229E | bvCoV | bCoV | hCoV HKU1 | caCoV | fCoV | hCoV OC43 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenine (A) | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| Cytosine (C) | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| Guanine (G) | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| Thymine (T) | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

| T3s | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.46 |

| C3s | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| A3s | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.30 |

| G3s | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.23 |

3.2. RSCU analysis

Codons with RSCU values were categorized into 3 groups: i) RSCU values <0.6 denote underrepresented codons (negatively biased); ii) values ranging from 0.6 to 1.6 constitute represented codons (with no bias); and iii) the values >1.6 indicate over-represented codons (positively biased). A3s and T3s were the most recurrent nucleotides in the represented (preferred) codons and C3s and G3s were the least frequent in overall studied viruses (Table 2 ). Eighteen amino acids (90 %) were observed with varied codon preferences (Phe, Leu, Ile, Val, Ser, Pro, Thr, Ala, Tyr, His, Gln, Asn, Lys, Asp, Glu, Cys, Arg, Gly) (Table 2). There were eight overrepresented amino acids (Leu, Ser, Pro, Thr, Ala, Tyr, Cys, Arg). Their corresponding codon values are represented in bold with shaded cells in Table 2.

Table 2.

Various CoVs representing RSCU values.

|

The values in bold are preferred codons for respective amino acids. The cells with negative biased values have a diagonal line. Over biased codon values are displayed in bold with shaded cells.

The amino acid Leu overbiased with CUU codon in all the genes except in hCoV HKU1 where it overbiased with UUA. The amino acid Ser overrepresented with UCU in all except UCA in ibCoV and bCoV. The overbiased codon for the amino acid Pro was CCA in MERS CoV and IbCoV, while in others it was CCU. The amino acid Thr over preferred ACU codon in all the genes except ibCoV and caCoV where its preferred ACA. The amino acid Ala highly overbiased with GCU codon in 12 genes while it favored ACA in IbCoV. Similarly, the amino acid Tyr encoded with UAC in MERS CoV while it overrepresented UAU in hCoV HKU1; Cys amino acid overbiased with UGC in pedCoV but UGU in other genes; Arg amino acid preferred CGU codon in pedCoV and CCoV while AGA dominated in others. Overall, among the NT3s of overrepresented or over biased codons, A3s and T3s dominated over C3s and G3s while in negative biased or underrepresented NT3s the order was G3s > C3s > A3s > T3s.

3.3. ENc and ENc plot

Generally, the values of ENc fall in-between 20–61. As the codon number decreases for a particular amino acid, it results in decrease of ENc value indicating higher codon bias. Conversely, increase in codon number corresponds with less or little codon bias for an amino acid. The ENc values for all the studied CoVs ranged from 40.43 to 53.85 (Table 3 ). Generally, the estimated average ENc values of RNA viruses span from 38.9 to 58.3 (Jenkins and Holmes, 2003). High ENc values suggest that the CoVs genes are highly conserved along with effective replication, whereas the lowest ENc value i.e. 20 reflects codon usage with extreme bias (one amino acid is coded by a single codon). Our study observed 18 amino acids having different synonymous codons. Furthermore, the RNA viruses usually consist of high ENc values which help it in replication and host adaption with preferred codons.

Table 3.

Codon Usage Indices of various CoVs.

| pedCoV | MERS CoV | ibCoV | cCoV | dCoV | tgCoV | hCoV 229E | bvCoV | bCoV | hCoV HKU1 | caCoV | fCoV | hCoV OC43 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENc | 53.85 | 49.53 | 48.84 | 45.84 | 53.6 | 50.74 | 46.95 | 51.14 | 50.32 | 40.43 | 49.82 | 50.86 | 53.85 |

| GC3s | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.38 |

| GC | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.46 |

| GRAVY | −1.07 | −0.86 | −1.01 | −0.89 | −0.45 | −0.87 | −0.57 | −0.82 | −0.84 | −0.84 | −0.43 | −1.02 | −0.86 |

| AROMO | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

An ENc plot is useful in analyzing mutational pressure and compositional constraints on codon usage and the compositional bias denoted by the points on the standard curve of ENc and GCs relation. Other forces influencing mutational bias are defined by the points beneath the standard curve. In all the viruses, all points were located below the standard curve, hence suggesting that codon usage bias was influenced by compositional constraints and other factors like virus host interactions and natural selection may influence codon bias.

Correlation values ranged from r = 0.0005 (fCoV) to 0.924 (bvCoV) as shown in Fig. 1. Significance levels were attained in various correlation analyses presented in a supplementary data file. The correlation between GC3s and ENc of ibCoV, tgCoV and bvCoV had a high significance (P < 0.001) revealing mutational bias influence along with extra codon usage bias. Whereas the rest of the CoVs did not yield significant correlations reflecting less influence of compositional constraints.

3.4. Neutrality plot

Neutrality plot analyze the neutrality of evolution by evaluating the impact of selection and mutation on codon usage bias. The significant correlation of GC3s and GC1,2 s was achieved through random selection when the genes lie on the slope of unity and then the particular gene is said to be under neutral mutation. The directional mutation pressure on codon usage occurs as the slope moves towards the x-axis. GC1, 2 s were plotted against GC3s and the slope implies the motion at which the mutation and selection forces evolved. The coefficient of regression denotes the equilibrium coefficient of mutation selection as shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Neutrality Plots of N genes from 13 different CoVs.

The GC nucleotide base frequencies at the third positions (GC3s) were plotted against the GC frequencies of first and second positions (GC)

The correlation analyses showed a very high correlation in pedCoV followed by MERS CoV, dCoV, bCoV and fCoV with r values 0.81, 0.68, -0.47, 0.98, and 0.58 respectively. The used N gene sequences for pedCoV were obtained from a broad range of timescale covering from March 2007 to August 2017. In contrast, MERS CoV N gene sequences were from July 2014 to January 2018. This might have reflected on the rate of compositional variations and adaptation to the host. Therefore, pedCoV showed more attempts to adapt the host by changing its genomic composition. Since MERS CoV is still considered as the emerging virus, its genomic composition is still evolving and its host adaptation is still a matter of debate. Three of the viruses showed moderate or medium correlation i.e. cCoV, hCoV 229E and caCoV with the following r values: 0.35, -0.41 and -0.5 (negative correlation). The slopes of regression ranged from -0.8954 to 0.5891 in all the studied viruses represented in Fig. 2. Therefore, this reveals the directional mutational pressure and neutrality influenced them. The supplementary data file includes the AROMO and GRAVY analyses which revealed moderate correlations among the studied CoVs N genes and their varying significance levels likely due to ENc, GC3s, GC variations. Thus, we can infer the codon usage influences from aromaticity and hydropathicity.

4. Discussion

Computational approaches are linked with most of the research studies including genomic analyses, evolution and drug discovery etc. (Kandeel et al., 2009a, b; Kandeel et al., 2009c). In the present work we assessed N gene of different CoVs with various factors such as natural selection, mutational selection and others to determine the codon bias and codon usage indices which regulate virion assembly and transcription of viral RNA in CoVs. The nucleotide contents revealed higher AT% and low GC% as it is common in RNA viruses such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) (Jenkins and Holmes, 2003; Gu et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2005). The ENc values >35 indicates the slight codon bias due to mutation pressure or nucleotide compositional constraints. This suggests that the RNA viruses with high ENc values adapt to the host with various preferred codons (Jenkins and Holmes, 2003). The positively biased or represented codons of the present study are similar to the two other studies on MERS CoV proteases and pandemic influenza virus (H1N1 and in H3N2) (Kumar et al., 2016; Kandeel and Altaher, 2017). In zika virus and tembusu virus codon usage was driven by the mutation bias (Cristina et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015) while in Parvoviridae and pedCoV it was dominated by selection pressure (Shi et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2014b). Some of the viruses observed with the codon bias related to their hosts during their adaptation (Chantawannakul and Cutler, 2008; Bahir et al., 2009; Cheng et al., 2012; Kattoor et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2015; Nasrullah et al., 2015). Studies directed at the conserved regions of viral proteins are useful for developing diagnostic reagents and probes for detecting a range of viruses and isolates in one test and for vaccine development (Du et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2019). In view of the lower mutation rates and relatively conserved sequences of the coronavirus (CoV) N gene, it would be ideal for studying these genes as an intermediary step in the development of vaccines and diagnostics for these viruses. The present study aids in the understanding of different factors influencing the variations of the N gene among various CoVs and their relationships with their hosts.

Author statement

Dear Dr. Paul

Our manuscript titled “Genomic variations in the N-gene of various Coronaviruses” assess nucleotide and aminoacid variations among the 13 different Coronaviruses and the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All the authors have been contributed in this manuscript.

I would like to inform you regarding the addition of another author who helped in the manuscript revision for which I had emailed you and there is a slight change in affiliation. The genbank accessions were included for all the viruses in the xl file as a supplementary data. Thanking you for your time and support.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abdullah Sheikh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Abdulla Al-Taher: Visualization, Investigation. Mohammed Al-Nazawi: Supervision. Abdullah I. Al-Mubarak: Writing - review & editing. Mahmoud Kandeel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Validation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University for the financial support under strategic projects track [grant number 171001].

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.113806.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ahn I., Jeong B.J., Son H.S. Comparative study of synonymous codon usage variations between the nucleocapsid and spike genes of coronavirus, and C-type lectin domain genes of human and mouse. Exp. Mol. Med. 2009;41:746. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.10.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahir I., Fromer M., Prat Y., Linial M. Viral adaptation to host: a proteome‐based analysis of codon usage and amino acid preferences. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:311. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behura S.K., Severson D.W. Codon usage bias: causative factors, quantification methods and genome‐wide patterns: with emphasis on insect genomes. Biol. Rev. 2013;88:49–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M., Manasse T.-L., Tan Y.-J., Fielding B.C. Characterisation of human coronavirus-NL63 nucleocapsid protein. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012;11:13962–13968. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E.G., Miao C., Haupt T.E., Anderson L.J., Haynes L.M. Development of a recombinant truncated nucleocapsid protein based immunoassay for detection of antibodies against human coronavirus OC43. J. Virol. Methods. 2011;177:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Springer; 1995. The Coronavirus Surface Glycoprotein, the Coronaviridae; pp. 73–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney J.L., Clark P.L. Roles for synonymous codon usage in protein biogenesis. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2015;44:143–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-034333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantawannakul P., Cutler R.W. Convergent host-parasite codon usage between honeybee and bee associated viral genomes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008;98:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che X.Y., Hao W., Wang Y., Di B., Yin K., Xu Y.C., Feng C.S., Wan Z.Y., Cheng V.C., Yuen K.Y. Nucleocapsid protein as early diagnostic marker for SARS. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:1947–1949. doi: 10.3201/eid1011.040516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.L., Lee W., Hottes A.K., Shapiro L., McAdams H.H. Codon usage between genomes is constrained by genome-wide mutational processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:3480–3485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307827100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen Y.-F. Analysis of synonymous codon usage patterns in duck hepatitis A virus: a comparison on the roles of mutual pressure and natural selection. Virusdisease. 2014;25:285–293. doi: 10.1007/s13337-014-0191-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Shi Y., Deng H., Gu T., Xu J., Ou J., Jiang Z., Jiao Y., Zou T., Wang C. Characterization of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus codon usage bias. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;28:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X.F., Wu X.Y., Wang H.Z., Sun Y.Q., Qian Y.S., Luo L. High codon adaptation in citrus tristeza virus to its citrus host. Virol. J. 2012;9:113. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLC Genomics Workbench 12.0 (QIAGEN, Aarhus, Denmark). https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/. (Accessed 20 January 2018).

- Cristina J., Moreno P., Moratorio G., Musto H. Genome-wide analysis of codon usage bias in Ebolavirus. Virus Res. 2015;196:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea L., Pintó R.M., Bosch A., Musto H., Cristina J. A detailed comparative analysis on the overall codon usage patterns in hepatitis A virus. Virus Res. 2011;157:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di B., Hao W., Gao Y., Wang M., Wang Y.D., Qiu L.W., Wen K., Zhou D.H., Wu X.W., Lu E.J., Liao Z.Y., Mei Y.B., Zheng B.J., Che X.Y. Monoclonal antibody-based antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reveals high sensitivity of the nucleocapsid protein in acute-phase sera of severe acute respiratory syndrome patients. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2005;12:135–140. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.1.135-140.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle W.F. You are what you eat: a gene transfer ratchet could account for bacterial genes in eukaryotic nuclear genomes. Trends Genet. 1998;14:307–311. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L., Zhou Y., Jiang S. Research and development of universal influenza vaccines. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta N.K., Mazumdar K., Lee B.H., Baek M.W., Kim D.J., Na Y.R., Park S.H., Lee H.K., Kariwa H., Park J.H. Search for potential target site of nucleocapsid gene for the design of an epitope-based SARS DNA vaccine. Immunol. Lett. 2008;118:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellenberg K., Hauser N.C., Brors B., Neutzner A., Hoheisel J.D., Vingron M. Correspondence analysis applied to microarray data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:10781–10786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181597298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Lu G., Qi J., Li Y., Wu Y., Deng Y., Geng H., Li H., Wang Q., Xiao H. Structure of the fusion core and inhibition of fusion by a heptad repeat peptide derived from the S protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2013;87:13134–13140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02433-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre M.J. Academic Press; London: 1984. Theory and Applications of Correspondence Analysis. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gu W., Zhou T., Ma J., Sun X., Lu Z. Analysis of synonymous codon usage in SARS Coronavirus and other viruses in the Nidovirales. Virus Res. 2004;101:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Du Q., Lau S., Manopo I., Lu L., Chan S.W., Fenner B.J., Kwang J. Characterization of monoclonal antibody against SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid antigen and development of an antigen capture ELISA. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;127:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemura T. Codon usage and tRNA content in unicellular and multicellular organisms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1985;2:13–34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins G.M., Holmes E.C. The extent of codon usage bias in human RNA viruses and its evolutionary origin. Virus Res. 2003;92:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.F., Schnell, M., Hensley, L.E., Wirblich, C., Coleman, C.M. and Frieman, M.B. 2019. Multivalent vaccines for rabies virus and coronoviruses, U.S. Patent Application 16/091,005.

- Kanaya S., Kinouchi M., Abe T., Kudo Y., Yamada Y., Nishi T., Mori H., Ikemura T. Analysis of codon usage diversity of bacterial genes with a self-organizing map (SOM): characterization of horizontally transferred genes with emphasis on the E. Coli O157 genome. Gene. 2001;276:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeel M., Altaher A. Synonymous and biased codon usage by MERS CoV papain-like and 3CL-proteases. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017;40:1086–1091. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b17-00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeel M., Kato A., Kitamura Y., Kitade Y. Vol. 53. 2009. Thymidylate kinase: the lost chemotherapeutic target; pp. 283–284. (Nucleic Acids Symposium Series). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeel M., Kitamura Y., Kitade Y. Vol. 53. 2009. The exceptional properties of plasmodium deoxyguanylate pathways as a potential area for metabolic and drug discovery studies; pp. 39–40. (Nucleic Acids Symposium Series). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeel M., Miyamoto T., Kitade Y. Bioinformatics, enzymologic properties, and comprehensive tracking of Plasmodium falciparum nucleoside diphosphate kinase. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009;32:1321–1327. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karniychuk U.U. Analysis of the synonymous codon usage bias in recently emerged enterovirus D68 strains. Virus Res. 2016;223:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattoor J.J., Malik Y.S., Sasidharan A., Rajan V.M., Dhama K., Ghosh S., Banyai K., Kobayashi N., Singh R.K. Analysis of codon usage pattern evolution in avian rotaviruses and their preferred host. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;34:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N., Bera B.C., Greenbaum B.D., Bhatia S., Sood R., Selvaraj P., Anand T., Tripathi B.N., Virmani N. Revelation of influencing factors in overall codon usage bias of equine influenza viruses. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.K., Lee B.H., Dutta N.K., Seok S.H., Baek M.W., Lee H.Y., Kim D.J., Na Y.R., Noh K.J., Park S.H., Kariwa H., Nakauchi M., Maile Q., Heo S.J., Park J.H. Detection of antibodies against SARS-Coronavirus using recombinant truncated nucleocapsid proteins by ELISA. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;18:1717–1721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F.Y., Lin L.C., Ying T.H., Yao C.W., Tang T.K., Chen Y.W., Hou M.H. Immunoreactivity characterisation of the three structural regions of the human coronavirus OC43 nucleocapsid protein by Western blot: implications for the diagnosis of coronavirus infection. J. Virol. Methods. 2013;187(2):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A.T., Sharp P.M. Evolution of codon usage patterns: the extent and nature of divergence between Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5289–5295. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loa C.C., Lin T.L., Wu C.C., Bryan T.A., Hooper T., Schrader D. Expression and purification of turkey coronavirus nucleocapsid protein in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. Methods. 2004;116:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.P., Liu Z.X., Hao L., Ma J.Y., Liang Z.L., Li Y.G., Ke H. Analysing codon usage bias of cyprinid herpesvirus 3 and adaptation of this virus to the hosts. J. Fish Dis. 2015;38:665–673. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maache M., Komurian-Pradel F., Rajoharison A., Perret M., Berland J.-L., Pouzol S., Bagnaud A., Duverger B., Xu J., Osuna A. False-positive results in a recombinant severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) nucleocapsid-based western blot assay were rectified by the use of two subunits (S1 and S2) of spike for detection of antibody to SARS-CoV. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:409–414. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.3.409-414.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride R., van Zyl M., Fielding B.C. The coronavirus nucleocapsid is a multifunctional protein. Viruses. 2014;6:2991–3018. doi: 10.3390/v6082991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Gojobori T., Ikemura T. Codon usage tabulated from international DNA sequence databases: status for the year 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28 doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.292. 292-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrullah I., Butt A.M., Tahir S., Idrees M., Tong Y. Genomic analysis of codon usage shows influence of mutation pressure, natural selection, and host features on Marburg virus evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:174. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0456-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman B.W., Kiss G., Kunding A.H., Bhella D., Baksh M.F., Connelly S., Droese B., Klaus J.P., Makino S., Sawicki S.G. A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology. J. Struct. Biol. 2011;174:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H., Lawrence J.G., Groisman E.A. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature. 2000;405:299. doi: 10.1038/35012500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peden J.F. University of Nottingham; 2000. Analysis of Codon Usage; p. 2000.http://codonw.sourceforge.net/) (Accessed 20 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perrière G., Thioulouse J. Use and misuse of correspondence analysis in codon usage studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4548–4555. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risco C., Antón I.M., Enjuanes L., Carrascosa J.L. The transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus contains a spherical core shell consisting of M and N proteins. J. Virol. 1996;70:4773–4777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4773-4777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruch T., Machamer C. The coronavirus E protein: assembly and beyond. Viruses. 2012;4:363–382. doi: 10.3390/v4030363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P.M., Li W.H. The rate of synonymous substitution in enterobacterial genes is inversely related to codon usage bias. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:222–230. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P.M., Stenico M., Peden J.F., Lloyd A.T. Codon usage: mutational bias, translational selection, or both. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1993;21:835–841. doi: 10.1042/bst0210835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S.L., Jiang Y.R., Liu Y.Q., Xia R.X., Qin L. Selective pressure dominates the synonymous codon usage in parvoviridae. Virus Genes. 2013;46:10–19. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S.-L., Jiang Y.-R., Yang R.-S., Wang Y., Qin L. Codon usage in Alphabaculovirus and Betabaculovirus hosted by the same insect species is weak, selection dominated and exhibits no more similar patterns than expected. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;44:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Snijder E.J. 2005. Coronaviruses, Toroviruses, and Arteriviruses. Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections. [Google Scholar]

- Sueoka N. Directional mutation pressure and neutral molecular evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1988;85:2653–2657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Deming M., Rockx B., Liddington R.C., Zhu Q.K., Baric R.S., Marasco W.A. Effects of human anti-spike protein receptor binding domain antibodies on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralization escape and fitness. J. Virol. 2014;88:13769–13780. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02232-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supek F. The code of silence: widespread associations between synonymous codon biases and gene function. J. Mol. Evol. 2016;82:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00239-015-9714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Brown C.J., Forney L.J., Top E.M. Comparison of correspondence analysis methods for synonymous codon usage in bacteria. Dna Res. 2008;15:357–365. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timani K.A., Ye L., Zhu Y., Wu Z., Gong Z. Cloning, sequencing, expression, and purification of SARS-associated coronavirus nucleocapsid protein for serodiagnosis of SARS. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;30:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hemert F., van der Kuyl A.C., Berkhout B. Impact of the biased nucleotide composition of viral RNA genomes on RNA structure and codon usage. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97:2608–2619. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasmoen T.L., Kadakia N.P., Unfer R.C., Fickbohm B.L., Cook C.P., Chu H.J., Acree W.M. Protection of cats from infectious peritonitis by vaccination with a recombinant raccoon poxvirus expressing the nucleocapsid gene of feline infectious peritonitis virus. In: Talbot P.J., Levy G.A., editors. Corona- and Related Viruses. Springer; Boston, MA: 1995. pp. 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese C.R. On the evolution of cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:8742–8747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132266999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Yan S. Reasoning of spike glycoproteins being more vulnerable to mutations among 158 coronavirus proteins from different species. J. Mol. Model. 2005;11:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s00894-004-0210-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.S., Hsieh Y.C., Su I.J., Lin T.H., Chiu S.C., Hsu Y.F., Lin J.H., Wang M.C., Chen J.Y., Hsiao P.W., Chang G.D., Wang A.H., Ting H.W., Chou C.M., Huang C.J. Early detection of antibodies against various structural proteins of the SARS-associated coronavirus in SARS patients. J. Biomed. Sci. 2004;11:117–126. doi: 10.1007/BF02256554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.D., Shang B., Yang R.F., Hao Y., Hai Z., Xu S., Ji Y.Y., Ying L., Di Wu Y., Lin G.M. The spike protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is cleaved in virus infected Vero-E6 cells. Cell Res. 2004;14:400. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Stevens V., Berry J.D., Crameri G., McEachern J., Tu C., Shi Z., Liang G., Weingartl H., Cardosa J., Eaton B.T., Wang L.F. Determination and application of immunodominant regions of SARS coronavirus spike and nucleocapsid proteins recognized by sera from different animal species. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008;331:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Yan B., Chen S., Wang M., Jia R., Cheng A. Evolutionary characterization of Tembusu virus infection through identification of codon usage patterns. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;35:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T., Gu W., Ma J., Sun X., Lu Z. Analysis of synonymous codon usage in H5N1 virus and other influenza A viruses. Biosystems. 2005;81:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.