Abstract

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is a rare, distinct disorder that is sufficiently different from the other diseases in the group of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias to be designated as a separate entity. In its most typical presentation, it is characterized by dyspnea and cough, with multiple patchy alveolar opacities on pulmonary imaging. Definite diagnosis is obtained by the finding of buds of granulation tissue in the distal airspaces at lung biopsy. No cause (as infection, drug reaction, or associated disease as connective tissue disease) is found. Corticosteroid treatment is rapidly effective, but relapses are common on reducing or stopping treatment.

Definition and diagnostic criteria

Definition and terminology

Organizing pneumonia is defined by a histologic pattern, and the corresponding clinical-radiologic-pathologic diagnosis is cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) when no definite cause (eg, infection) or characteristic clinical context (eg, connective tissue disease) is found.

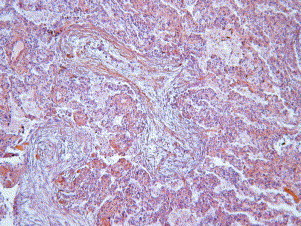

The histologic pattern is defined by the presence of buds of granulation tissue (which consist of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts embedded in a loose connective matrix) present in the lumen of the distal airspaces (ie, the alveoli, alveolar ducts, and possibly bronchioles) (Fig. 1 ). Because buds may be found in the distal bronchioles (so-called “proliferative bronchiolitis”), COP also has been termed “idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.” Because of some ambiguity with the other types of bronchiolitis (as constrictive bronchiolitis usually associated with airflow obstruction) and because organizing pneumonia is the characteristic and predominant pathologic pattern, with bronchiolitis only an accessory finding, the current internationally recognized terminology is COP [1].

Fig. 1.

Buds of granulation tissue in the lumen of the distal airspaces.

Diagnostic criteria

Pathologic diagnosis

The pathologic diagnosis of the pattern of organizing pneumonia first requires the finding of the characteristic buds of granulation tissue in the alveoli. “Butterflies” of granulation tissue may extend from one alveolus to the adjacent one through the pores of Kohn. The process is patchy, and usually the lesions are all the same age. In some cases, however, the different stages of organization (from fibrinoid inflammatory cell clusters to mature fibrotic buds) may be found on the same biopsy specimen. The lesions are centered on the small airways and distal to them. A mild cellular inflammatory infiltration of the interstitium is present. Type II cell metaplasia may be associated. Foamy macrophages are commonly present in the airspaces [2].

To make a diagnosis of COP, the pattern of organizing pneumonia must be prominent and not just an accessory finding of another well-defined pattern of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (eg, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, especially cellular or cellular and fibrotic, in which intra-alveolar buds of granulation tissue are found in approximately 50% of cases). The negative findings for the diagnosis of organizing pneumonia pattern include the lack of prominent cellular and significant interstitial fibrosis, the lack of fibroblastic foci, the absence of granulomas, the lack of hyaline membranes and vasculitis, and little or no eosinophilia [3]. Other disorders in which organizing pneumonia may be present (and even represent the major histologic finding) also must be excluded (eg, the bronchiolitis obliterans–organizing pneumonia variant of Wegener's granulomatosis) [4].

Clinical–radiologic–pathologic diagnosis

The final diagnosis that takes into account the clinical and imaging features, together with the pathologic clues to diagnosis, is a dynamic process that integrates the clinical manifestations (which are entirely aspecific), the imaging features (which are often highly evocative), and the decision of lung biopsy to obtain a definite diagnosis. Once a confident diagnosis of organizing pneumonia is obtained, an etiologic diagnosis is necessary before accepting that organizing pneumonia is really cryptogenic.

Etiologic diagnosis of organizing pneumonia

In addition to defining COP (clinical–radiologic–pathologic diagnosis), the organizing pneumonia pathologic pattern may be found in several other settings because it is a nonspecific reaction that results from alveolar damage with intra-alveolar leakage of plasma proteins (especially coagulation factors), which further undergoes a process of intra-alveolar organization.

Organizing pneumonia may result from infection by bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi (Box 1 ). (It is worthwhile to remember that it was initially described at the beginning of the twentieth century in nonresolving pneumococcal pneumonia.) Drugs are other established causes of organizing pneumonia (Box 2 ). The syndrome of organizing pneumonia “primed” by radiation therapy for breast cancer closely resembles COP [25], [26], [27]. It differs from radiation pneumonitis by the involvement of nonirradiated parts of the lungs, the possible migration of opacities, and the lack of chronic sequelae. The syndrome develops within weeks or months after radiation therapy. As in COP, corticosteroids are efficient, but relapses may occur after reducing or stopping treatment. Radiation therapy to the breast induces bilateral lymphocytic alveolitis [28], but only a few patients develop organizing pneumonia, which suggests that a second hit or an individual genetic or acquired susceptibility is necessary for organizing pneumonia to occur.

Box 1.

Infectious causes of organizing pneumonia

Bacteria

Chlamydia pneumoniae

Coxiella burnetii

Legionella pneumophila

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Nocardia asteroides

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Serratia marcescens

Staphylococcus aureus

Streptococcus group B (newborn treated by extracorporeal oxygenation)

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Viruses

Herpesvirus

HIV

Influenza virus

Parainfluenza virus

Cytomegalovirus

Human herpesvirus-7 (after lung transplantation)

Parasites

Plasmodium vivax

Fungi

Cryptococcus neoformans

Penicillium janthinellum

Pneumocystis carinii (after highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with AIDS)

Data from Cordier JF. Organising pneumonia. Thorax 2000;55:318–28; and Refs. [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15].

Box 2.

Drugs identified as causes of organizing pneumonia

5-Aminosalicylic acid (in patients treated by this drug for ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease, which may be associated with organizing pneumonia)

Acebutolol

Acramin FWN

Amiodarone

Amphotericine

Bleomycin

Busulphan

Carbamazepine (in the course of lupus syndrome induced by the drug)

Cephalosporin (cefradin)

Cocaine

Doxorubicin

Gold salts (in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, which may be associated with organizing pneumonia)

Hexamethonium

Interferon α

Interferon α + cytosine arabinoside

Interferon + ribavirin

Interferon β1a

l-Tryptophan

Mesalazine

Methotrexate

Minocycline

Nitrofurantoin

Nilutamide

Paraquat

Phenytoin

Sotalol

Sulfasalazine (in patients treated by this drug for ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease, which may be associated with organizing pneumonia)

Tacrolimus

Ticlopidine (in a patient with temporal arteritis)

Trastuzumab (herceptin)

Vinbarbital-aprobarbital

Data from Cordier JF. Organising pneumonia. Thorax 2000;55:318–28; and Refs. [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24].

Organizing pneumonia also may occur in the specific context of well-characterized disorders, such as the connective tissue disorders (dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome), ulcerative colitis, or after lung transplantation or bone marrow grafting (Box 3 ).

Box 3.

Organizing pneumonia of undetermined cause in specific contexts

Connective tissue disorders

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Others: Sjögren's syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma

Bone marrow graft and transplantation

Bone marrow graft

Lung transplantation

Liver transplantation

Hematologic malignancies

Myelodysplasia, leukemia, myeloproliferative disorders

Miscellaneous

Lung cancer, sarcoidosis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, Sweet syndrome, polymyalgia rheumatica, common variable immunodeficiency, Wegener's granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, thyroid disease, cystic fibrosis, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, spice processing

Data from Cordier JF. Organising pneumonia. Thorax 2000;55:318–28; and Refs. [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53].

Clinical manifestations of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

The clinical manifestations of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia have been described in several series [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74]. COP affects men and women equally (although there is a female predominance in some series), especially between 50 and 60 years, and it is not related to smoking. (Nonsmokers or ex-smokers represent the majority in most series.) COP occasionally has been reported in childhood [75].

Symptoms generally develop subacutely with a flu-like syndrome that lasts for a few weeks and is accompanied by mild fever, anorexia, weight loss, sweats, nonproductive cough, and mild dyspnea. Chest pain, hemoptysis, and bronchorrhea are uncommon. The initial diagnosis usually is that of an infectious pulmonary disease; however, antibiotics are not efficient, even when drugs from different classes are used successively. Diagnosis is obtained only after several weeks (approximately 6–13). Occasionally symptoms are more severe, and some patients present with the characteristic features of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but this is an uncommon eventuality (see later discussion).

Physical examination is nonspecific. Fine crackles often are heard over affected pulmonary areas, but there are no wheezes. In contrast with the other idiopathic intestitial pneumonias, especially idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the crackles are not diffuse. Finger clubbing is not present.

Imaging

Chest radiography and high-resolution CT (HRCT) play major roles in raising a possible diagnosis of COP. The imaging features further represent the basis for defining the main characteristic types of COP [54], [56], [59], [65], [68], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83] as recently reviewed in detail [84].

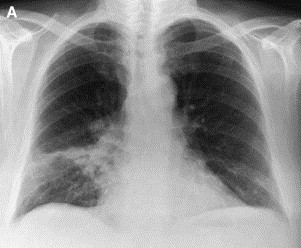

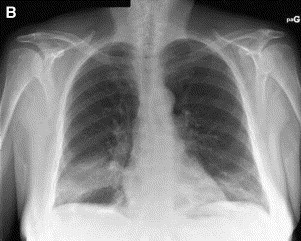

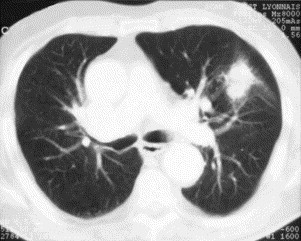

The typical imaging features of COP (classic COP) [54], [84] comprise patchy alveolar opacities on chest radiograph, usually bilateral, which may be migratory (Fig. 2 ). They usually predominate in the lower lung zones. On HRCT, their density varies from ground glass to consolidation. Their size ranges from a few centimeters to an entire lobe (Fig. 3 ). They are generally peripheral, but they may predominate less frequently in a peribronchovascular location (bronchocentric pattern). Sometimes these opacities take the shape of large nodules or masses that often contain an air bronchogram [85]. The clinical syndrome, together with such typical imaging features, evokes the possible diagnosis of COP for most chest physicians. In a review of HRCT scans from a series of patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia by two independent reviewers without knowledge of clinical or histologic data, a correct diagnosis of COP was made in 79% of cases [86]. This was the highest percentage of correct diagnoses among the different idiopathic interstitial pneumonias based on the finding of the characteristic features of patchy subpleural or peribronchovascular airspace consolidation often associated with areas of ground-glass attenuation.

Fig. 2.

Chest radiograph in a patient with typical COP. (A) Patchy alveolar opacity of right lower lobe. (B) Six days later, the distribution of the right lower lobe opacity changed, and a new contralateral basal opacity appeared.

Fig. 3.

HRCT in typical COP. (A) Patchy bilateral opacities in the lower lobes. (B) Bilateral extensive consolidation with air bronchogram in the lower lobes.

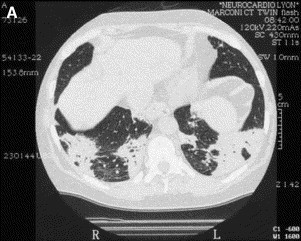

The second distinct clinical imaging presentation of COP is that of solitary focal COP that presents as a solitary nodule or mass (Fig. 4 ) and often is located in the upper lobes. Some patients are asymptomatic, and diagnosis and cure are obtained by surgical excision of the lesion, which is suspected to correspond to lung cancer. Some patients present with a clinical syndrome of chronic nonresolving pneumonia with persistent fever and inflammatory biologic manifestations despite antibiotics, however. Such patients may have hemoptysis, and cavitation of the mass may be present (especially on HRCT).

Fig. 4.

HRCT in solitary focal COP shows a pseudo-neoplastic mass.

The third distinct clinical imaging presentation of COP is that of infiltrative lung disease. On HRCT, interstitial opacities are often associated with superimposed small alveolar opacities. Initially, there is no honeycombing, although there are some reticular subpleural opacities and eventually honeycombing may develop over the long-term. This type of COP deserves further analysis because it is associated with more interstitial mononuclear inflammation and probably overlaps with other interstitial lung disease, especially nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. In the latter, focal organizing pneumonia is a common finding, and it is likely that in the past (when COP had only just been recognized as a clinical entity and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia was not yet individualized), cases of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia with some organizing pneumonia foci were labeled as COP. An overlap between cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and this type of COP is likely, with a good response to corticosteroid treatment and possible relapse on stopping it in both conditions.

Other imaging features of COP have been reported, including small nodular opacities, irregular linear opacities, bronchial wall thickening and dilatation pneumatocele, and multiple cavitary lung nodules. The micronodular pattern centered on the bronchioles may correspond to bronchiolitis with peribronchiolar organizing pneumonia [87]. Band-like areas of consolidation in the subpleural area (paralleling the chest wall) may be observed [88], especially during healing on corticosteroid treatment. (This finding is also present in some patients treated for eosinophilic pneumonia.) A reverse halo sign (central ground-glass opacity and surrounding airspace consolidation of crescentic or ring shape) may be found in some patients, usually in association with other types of opacity [89], [90], [91]. Air leak (eg, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum) is occasionally a feature of COP. These occurrences are only occasional, however, and do not represent an established clinicoradiologic category.

Laboratory findings and bronchoalveolar lavage

Laboratory findings are of little value in diagnosing COP. They usually show an increased level of blood leukocytes with an increase in the proportion of neutrophils. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are increased. Occasionally, antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor are present in the absence of patent connective tissue disease (usually at a low titer). Gammaglutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase are increased, and their mean values are higher in patients with multiple relapses than patients without relapse [55].

Bronchoalveolar lavage differential cell count demonstrates a “mixed pattern,” with a moderate increase in lymphocytes (approximately 25%–45%) with a decreased CD4/CD8 ratio in most cases, neutrophils (approximately 10%), and eosinophils (approximately 5%, and less than 25%, which is the lower limit usually accepted for a diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia) [54], [55], [56], [92], [93], [94]. Foamy macrophages often are present, and some mast cells and plasma cells may be found in some patients. In patients who presented with clinicoradiologic manifestations compatible with typical COP, an arbitrary set of bronchoalveolar lavage findings (lymphocytosis of more than 25% with a CD4/CD8 ratio <0.9, combined with at least two of the following criteria : foamy macrophages >20% or neutrophils >5% or eosinophils >2% and <25%) had a positive predictive value of 85% for COP [94].

Lung function tests

Lung function tests usually show a mild (or moderate) restrictive pattern. Airflow obstruction is not typically present, in contrast with pure bronchiolitis obliterans, although airflow obstruction may occur in patients with underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The carbon dioxide transfer factor is reduced, but the carbon dioxide transfer coefficient may be normal [54], [57], [59], [65], [72], [73].

Hypoxemia is present and usually mild [55], [56], [58]. More severe hypoxemia may occur in patients with severe, rapidly progressive diffuse COP, an underlying respiratory disease (eg, emphysema), or a right-to-left shunt at the alveolar level. The latter, which likely results from impaired gas exchange in alveoli occupied by buds and further impaired by hypoxic vasoconstriction, is recognized by the presence of an increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient while breathing 100% oxygen and a negative contrast echocardiography (no contrast visualized in the left atrium after injection into a peripheral vein) [95], [96].

Treatment of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

Although improvement of typical COP occasionally has been reported spontaneously or after treatment with erythromycin, corticosteroids are the current reference treatment of COP.

The clinical and imaging response to corticosteroids is rapid. Clinical manifestations abate within 48 hours, and chest radiographs show a complete resolution of the pulmonary opacities within a few weeks, without leaving significant functional or imaging sequelae. Although the efficiency of corticosteroids has been recognized for almost 20 years, the ideal dose and duration of treatment have not been established, however, which underlines once again the difficulty of therapeutic trials in rare, so-called “orphan” lung diseases.

Epler [97] proposed starting with high doses (1 mg/kg/day) of prednisone for 1 to 3 months, then 40 mg/day for 3 months, then 10 mg daily (or 20 mg every other day) for 1 year.

King and Mortenson [72] proposed starting with high doses (1–1.5 mg/kg/day for 4–8 weeks using ideal body weight) and then tapering to 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day for 4 to 6 weeks. After 3 to 6 months of corticosteroid therapy, if the patient's condition remains stable or improved, prednisone is gradually tapered to zero.

Our current treatment protocol [55] uses lower doses and shorter duration of treatment. We start with 0.75 mg/kg/day of prednisone for 4 weeks, then 0.5 mg/kg/day for 6 weeks, then 20 mg/day for 6 weeks, then 5 mg/day for 6 weeks.

Wells et al [98] from the Brompton Hospital, London, instituted high doses of methylprednisolone intravenously for 3 days (0.75–1 g), followed by 40 mg of prednisolone per day for 10 to 14 days, then 10 mg/day for the next 1 to 2 months, then 20 mg on alternate days for 1 year or longer if there is evidence of limited interstitial fibrosis on initial or subsequent CT.

Although the response to corticosteroids is excellent, a proportion of patients experience a relapse of COP. Some patients experience several relapses. The rate of relapses ranges from 13% [58] to 58% [55].

We studied the characteristics of relapses in 48 patients with biopsy-proven COP treated by corticosteroids with a mean follow-up of 35 ± 31 months after diagnosis [54]. The mean daily dose to treat the initial episode was 50 mg ± 17 mg at onset. One or more relapses (mean 2.4 ± 2.2) occurred in 58% of patients (one in 31% and two or more in 27%, with 19% having multiple [≥3] relapses). Sixty-eight percent of patients still were receiving corticosteroids when the first relapse occurred (mean daily dose, 12 mg ± 7 mg), with 75% receiving 0 to 10 mg/day, 21% receiving 11 to 20 mg/day, and one patient (4%) receiving more than 20 mg/day. These results suggest that relapse on more than 20 mg of prednisone per day is rare and should lead to a reconsideration of the diagnosis of COP (especially if not histologically established). The treatment of relapses in our protocol comprises 20 mg/day of prednisone (when relapse occurs at doses below this dosage) for 12 weeks, then the reduction of dosage follows the previously mentioned protocol used for the first episode.

The predictors of multiple relapses occurrence in our study were delayed treatment and mild cholestasis (elevated gamma-glutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase) [55]. The severity of hypoxemia at first presentation has been reported to be a determinant of subsequent relapse [50], but this was not confirmed in our study. Relapses were not associated with increased mortality or increased long-term functional morbidity. Using the protocol defined previously, we observed a significant reduction in cumulative steroid doses without adversely affecting outcome and relapse rate. Our current policy of treatment aims at obtaining a well-equilibrated balance between efficient treatment and adverse effects of corticosteroids by using low doses and relatively short treatment duration. We consider that a patient's preference must be taken into account when choosing between the risk of more relapses and fewer side effects and vice versa.

Severe and progressive cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

Rarely, patients with COP may present with severe respiratory impairment or progress toward respiratory failure that necessitates tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Some of them really have COP, but a proportion probably is affected by an overlapping condition.

Depending on the extent of organizing pneumonia and its progression before corticosteroid treatment is initiated, some patients fit initially with the clinical diagnosis of ARDS. The pathologic pattern is organizing pneumonia, however, and not the diffuse alveolar damage underlying ARDS or acute interstitial pneumonia (the idiopathic form of ARDS) [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104].

In such cases, once corticosteroids are introduced, the evolution is usually favorable. In a few reported cases, the addition of immunosuppressors to corticosteroids resulted in improvement not obtained hitherto by corticosteroids alone [96], [105], [106]. Whether improvement really resulted from immunosuppressors or merely from prolonged corticosteroids is not established, however.

Some patients with ARDS with an organizing pneumonia histologic pattern die from rapidly progressive disease, but these often correspond to patients with associated connective tissue disease or exposure to drugs or birds [107], [108]. In some of these patients, death may result from progression to fibrosis and honeycombing [107]. The presence of background remodeling of the pulmonary parenchyma with interstitial fibrosis, which is associated with dense eosinophilic hyalinization of the fibromyxoid plugs of airspace collagen, was reported as a pathologic predictor of poor outcome [109]. Some patients who fit the criteria for ARDS may have a well-tolerated hypoxemia that results from a right-to-left shunt at the alveolar level and does not necessitate ventilation.

Conditions that overlap with COP may explain the unfavorable course of some patients. The pathologic proliferative (organizing) phase of the diffuse alveolar damage that characterizes ARDS and acute interstitial pneumonia may overlap with organizing pneumonia because the organization of intraluminal exudate dominates the histologic picture in this proliferative stage [110], which may further progress to the fibrotic phase and ensuing death. The CT findings of organizing pneumonia are similar to those of severe acute respiratory syndrome, which correspond to diffuse alveolar damage [111]. Rapidly progressive COP and acute interstitial pneumonia may have overlapping clinical, radiologic, and histologic features [112], [113]. Studies are needed to elucidate the overlap of rapidly progressive COP, ARDS, and acute interstitial pneumonia, especially prognostic factors of response to corticosteroids.

A clinical picture of acute lung injury with a dominant histologic pattern of intra-alveolar fibrin and organizing pneumonia has been reported [114]. Patients present with acute-onset symptoms of dyspnea, fever, cough, and hemoptysis. Although associations are found in some patients (eg, infection, collagen vascular disease), others present with idiopathic disease. Some patients have a subacute illness and eventual recovery, whereas others have a fulminant progression to death within 1 month despite mechanical ventilation.

Histologically, the pattern of patchy intra-alveolar fibrin and organizing pneumonia is distinct from diffuse alveolar damage and organizing pneumonia. The main distinguishing histologic feature of organizing pneumonia is organized fibrin balls in acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia, whereas fibroblastic buds are dominant in organizing pneumonia. Previously, cases of COP with the presence of fibrin within buds of granulation tissue were reported to have a poor response to corticosteroids [115]. The relationship between cases of fatal COP and acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia remains to be determined [114].

The severity of COP also may result in some cases from its evolution toward fibrosis and honeycombing (and sometimes usual interstitial pneumonia). Some cases likely correspond to organizing pneumonia superimposed on a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern in patients with acute exacerbation or accelerated progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Diagnosis of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia in clinical practice

The diagnosis of organizing pneumonia (clinical-radiologic-imaging diagnosis) is definite in a patient with a typical pathologic pattern on a pulmonary biopsy of sufficient size to exclude another disorder, of which organizing pneumonia is just an associated component, together with compatible clinicoradiologic manifestations. The diagnosis is probable in patients with findings of organizing pneumonia on transbronchial biopsy and a typical clinicoradiologic presentation without pathologic confirmation. The diagnosis is possible in patients with typical clinicoradiologic presentation without biopsy confirmation.

In all cases, conditions that mimic COP (especially pulmonary lymphoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, and pulmonary thromboembolism) must be excluded by appropriate investigations if necessary, including especially bronchoalveolar lavage.

The etiologic diagnosis aims to rule out a cause of organizing pneumonia (especially infection, drug- or radiation-induced reaction, or an associated condition, such as connective tissue disease or systemic inflammatory disease). When all etiologic investigations produce negative results, organizing pneumonia may be called cryptogenic.

In any case—and especially when the diagnosis is not definite—when treatment has been initiated, a careful follow-up is necessary. If unusual clinicoradiologic pulmonary manifestations or systemic manifestations occur or if relapse occurs while on more than 20 mg/day of prednisone, the diagnosis must be reconsidered. In such eventuality, a video-assisted lung biopsy is often necessary.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: international multidisciplinary consensus. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colby T.V. Pathologic aspects of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Chest. 1992;102:38S–43S. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1_supplement.38s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitaichi M. Differential diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Chest. 1992;102:44S–49S. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1_supplement.44s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uner A.H., Rozum-Slota B., Katzenstein A.L. Bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia (BOOP)-like variant of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:794–801. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez de Llano L.A., Racamonde A.V., Bande M.J., Piquer M.O., Nieves F.B., Feijoo A.R. Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia associated with acute Coxiella burnetii infection. Respiration (Herrlisheim) 2001;68:425–427. doi: 10.1159/000050541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito I., Naito J., Kadowaki S., Mishima M., Ishida T., Hongo T. Hot spring bath and Legionella pneumonia: an association confirmed by genomic identification. Intern Med. 2002;41:859–863. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshinouchi T., Ohtsuki Y., Fujita J., Sugiura Y., Banno S., Sato S. A study on intraalveolar exudates in acute Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Acta Med Okayama. 2002;56:111–116. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akin J. Diagnostic dilemma: BOOP. Am J Med. 2000;109:500–508. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00565-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghidini A., Mariani E., Patregnani C., Marinetti E. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:843. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staud R., Ramos L.G. Influenza A-associated bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia mimicking Wegener's granulomatosis. Rheumatol Int. 2001;20:125–128. doi: 10.1007/s002960000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karakelides H., Aubry M.C., Ryu J.H. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia mimicking lung cancer in an immunocompetent host. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:488–490. doi: 10.4065/78.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross D.J., Chan R.C., Kubak B., Laks H., Nichols W.S. Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia: possible association with human herpesvirus-7 infection after lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2603–2606. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleindienst R., Fend F., Prior C., Margreiter R., Vogel W. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia associated with Pneumocystis carinii infection in a liver transplant patient receiving tacrolimus. Clin Transplant. 1999;13:65–67. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.t01-1-130111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wislez M., Bergot E., Antoine M., Parrot A., Carette M.F., Mayaud C. Acute respiratory failure following HAART introduction in patients treated for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:847–851. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2007034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis S.J., Cleverley J.R., Muller N.L. Drug-induced lung disease: high-resolution CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:1019–1024. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.4.1751019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banka R., Ward M.J. Bronchiolitis obliterans and organising pneumonia caused by carbamazepine and mimicking community acquired pneumonia. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:621–622. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.924.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs C., Slade M., Lavery B. Doxorubicin and BOOP: a possible near fatal association. Clin Oncol. 2002;14:262. doi: 10.1053/clon.2002.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel M., Ezzat W., Pauw K.L., Lowsky R. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia developing after initiation of interferon and cytosine arabinoside. Eur J Haematol. 2001;67:318–321. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2001.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar K.S., Russo M.W., Borczuk A.C., Brown M., Esposito S.P., Lobritto S.J. Significant pulmonary toxicity associated with interferon and ribavirin therapy for hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2432–2440. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferriby D., Stojkovic T. Clinical picture: bronchiolitis obliterans with organising pneumonia during interferon beta-1a treatment. Lancet. 2001;357:751. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saelens T., Lamblin C., Stojkovic T., Riera-Laussel B., Wallaert B., Tonnel A.B. Une pneumonie organisée secondaire à l'administration d'interféron béta 1a. [Organizing pneumonia secondary to administration of interferon β1a.] Rev Mal Respir. 2001;18:1S134. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fawcett I.W., Ibrahim N.B. BOOP associated with nitrofurantoin. Thorax. 2001;56:161. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron R.J., Kolbe J., Wilsher M.L., Lambie N. Bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia associated with the use of nitrofurantoin. Thorax. 2000;55:249–251. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radzikowska E., Szczepulska E., Chabowski M., Bestry I. Organising pneumonia caused by transtuzumab (Herceptin) therapy for breast cancer. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:552–555. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00035502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crestani B., Valeyre D., Roden S., Wallaert B., Dalphin J.C., Cordier J.F. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia syndrome primed by radiation therapy to the breast. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1929–1935. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9711036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bayle J.Y., Nesme P., Bejui-Thivolet F., Loire R., Guerin J.C., Cordier J.F. Migratory organizing pneumonitis “primed” by radiation therapy. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:322–326. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08020322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbetter K.R., Prakash U.B.S., Tazelaar H.D., Douglas W.W. Radiation-induced pneumonitis in the “nonirradiated” lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:27–36. doi: 10.4065/74.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts C.M., Foulcher E., Zaunders J.J., Bryant D.H., Freund J., Cairns D. Radiation pneumonitis: a possible lymphocyte-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:696–700. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-9-199305010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas W.W., Tazelaar H.D., Hartman T.E., Hartman R.P., Decker P.A., Schroeder D.R. Polymyositis-dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1182–1185. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2103110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu Y., Tsukagoshi H., Nemoto T., Honma M., Nojima Y., Mori M. Recurrent bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in a patient with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22:216–218. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0230-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patriarca F., Skert C., Sperotto A., Damiani D., Cerno M., Geromin A. Incidence, outcome, and risk factors of late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications after unrelated donor stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:1–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron F.A., Hermanne J.P., Dowlati A., Weber T., Thiry A., Fassotte M.F. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia and ulcerative colitis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:951–954. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freudenberger T.D., Madtes D.K., Curtis J.R., Cummings P., Storer B.E., Hackman R.C. Association between acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Blood. 2003;102:3822–3828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim K., Lee M.H., Kim J., Lee K.S., Kim S.M., Jung M.P. Importance of open lung biopsy in the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. Am J Hematol. 2002;71:75–79. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suratt B.T., Cool C.D., Serls A.E., Chen L., Varella-Garcia M., Shpall E.J. Human pulmonary chimerism after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Med. 2003;168:318–322. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-145OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes-Jordan A., Benaim E., Richardson S., Joglar J., Srivastava D.K., Bowman L. Open lung biopsy in pediatric bone marrow transplant patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:446–452. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown M.J., Miller R.R., Muller N.L. Acute lung disease in the immunocompromised host: CT and pathologic examination findings. Radiology. 1994;190:247–254. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.1.8259414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanamori H., Mishima A., Tanaka M., Yamaji S., Fujisawa S., Koharazawa H. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) with suspected liver graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Transpl Int. 2001;14:266–269. doi: 10.1007/s001470100330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanamori H., Fujisawa S., Tsuburai T., Yamaji S., Tomita N., Fujimaki K. Increased exhaled nitric oxide in bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:1356–1358. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211150-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopkins P.M., Aboyoun C.L., Chhajed P.N., Malouf M.A., Plit M.L., Rainer S.P. Prospective analysis of 1,235 transbronchial lung biopsies in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:1062–1067. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeAngelo A.J., Ouellette D. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in an orthotopic liver transplant patient. Transplantation. 2002;73:544–546. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200202270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hummel P., Cangiarella J.F., Cohen J.M., Yang G., Waisman J., Chhieng D.C. Transthoracic fine-needle aspiration biopsy of pulmonary spindle cell and mesenchymal lesions: a study of 61 cases. Cancer. 2001;93:187–198. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Zincer F., Juturi J.V., Hsi E.D., Hoeltge G.A., Rybicki L.A., Kalaycio M.E. A pulmonary syndrome in patients with acute myelomonocytic leukemia and inversion of chromosome 16. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:103–109. doi: 10.3109/10428190309178819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mokhtari M., Bach P.B., Tietjen P.A., Stover D.E. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in cancer: a case series. Respir Med. 2002;96:280–286. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez E., Lopez D., Buges J., Torres M. Sarcoidosis-associated bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2148–2149. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.17.2148-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peschard S., Akpan T., Brinkane A., Gaudin B., Leroy-Terquem E., Levy R. Bronchiolite oblitérante avec pneumonie organisée et rectocolite hémorragique. [Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia and ulcerative colitis.] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2000;24:848–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casey M.B., Tazelaar H.D., Myers J.L., Hunninghake G.W., Kakar S., Kalra S.X. Noninfectious lung pathology in patients with Crohn's disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:213–219. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Longo M.I., Pico M., Bueno C., Lazaro P., Serrano J., Lecona M. Sweet's syndrome and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Am J Med. 2001;111:80–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00789-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stey C., Truninger K., Marti D., Vogt P., Medici T.C. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:926–929. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d37.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe K., Senju S., Maeda F., Yshida M. Four cases of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia associated with thyroid disease. Respiration (Herrlisheim) 2000;67:572–576. doi: 10.1159/000067477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hausler M., Meilicke R., Biesterfeld S., Kentrup H., Friedrichs F., Kusenbach G. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: a distinct pulmonary complication in cystic fibrosis. Respiration (Herrlisheim) 2000;67:316–319. doi: 10.1159/000029517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guzman E.J., Smith A.J., Tietjen P.A. Bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:382–383. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alleman T., Darcey D.J. Case report: bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in a spice process technician. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:215–216. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cordier J.F., Loire R., Brune J. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: definition of characteristic clinical profiles in a series of 16 patients. Chest. 1989;96:999–1004. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazor R., Vandevenne A., Pelletier A., Leclerc P., Court-Fortune I., Cordier J.F. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: characteristics of relapses in a series of 48 patients. The Groupe d'Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines” Pulmonaires (GERM”O”P) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:571–577. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9909015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang J., Han J., Kim D.W., Lee I., Lee K.Y., Jung S. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: clinicopathologic review of a series of 45 Korean patients including rapidly progressive form. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:179–186. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Epler G.R., Colby T.V., McLoud T.C., Carrington C.B., Gaensler E.A. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:152–158. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lohr R.H., Boland B.J., Douglas W.W., Dockrell D.H., Colby T.V., Swensen S.J. Organizing pneumonia: features and prognosis of cryptogenic, secondary, and focal variants. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1323–1329. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.12.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Izumi T., Kitaichi M., Nishimura K., Nagai S. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: clinical features and differential diagnosis. Chest. 1992;102:715–719. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cazzato S., Zompatori M., Baruzzi G., Schiattone M.L., Burzi M., Rossi A. Bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia: an Italian experience. Respir Med. 2000;94:702–708. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boots R.J., McEvoy J.D., Mowat P., Le Fevre I. Bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia: a clinical and radiological review. Aust N Z J Med. 1995;25:140–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1995.tb02826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alasaly K., Muller N., Ostrow D.N., Champion P., FitzGerald J.M. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: a report of 25 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995;74:201–211. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davison A.G., Heard B.E., McAllister W.A.C., Turner-Warwick M.E. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis. Q J Med. 1983;52:382–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katzenstein A.L., Myers J.L., Prophet W.D., Corley L.S., Shin M.S. Bronchiolitis obliterans and usual interstitial pneumonia: a comparative clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:373–381. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198606000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guerry-Force M.L., Muller N.L., Wright J.L., Wiggs B., Coppin C., Pare P.D. A comparison of bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, usual interstitial pneumonia, and small airways disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:705–712. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bellomo R., Finlay M., McLaughlin P., Tai E. Clinical spectrum of cryptogenic organising pneumonitis. Thorax. 1991;46:554–558. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.8.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spiteri M.A., Klernerman P., Sheppard M.N., Padley S., Clark T.J., Newman-Taylor A. Seasonal cryptogenic organising penumonia with biochemical cholestasis: a new clinical entity. Lancet. 1992;340:281–284. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92366-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Flowers J.R., Clunie G., Burke M., Constant O. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: the clinical and radiological features of seven cases and a review of the literature. Clin Radiol. 1992;45:371–377. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80993-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyagawa Y., Nagata N., Shigematsu N. Clinicopathological study of migratory lung infiltrates. Thorax. 1991;46:233–238. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lamont J., Verbeken E., Verschakelen J., Demedts M. Bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia: a report of 11 cases and a review of the literature. Acta Clin Belg. 1998;53:328–336. doi: 10.1080/17843286.1998.11754185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dur P., Vogt P., Russi E. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia” (BOOP): chronisch organisierende Pneumonie (COP). Diagnostik, therapie und verlauf. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1993;123:1429–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.King T.E., Mortenson R.L. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis: the North American experience. Chest. 1992;102:8S–13S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Costabel U., Teschler H., Schoenfeld B., Hartung W., Nusch A., Guzman J. BOOP in Europe. Chest. 1992;102:14S–20S. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1_supplement.14s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yamamoto M., Ina Y., Kitaichi M., Harasawa M., Tamura M. Clinical features of BOOP in Japan. Chest. 1992;102:21S–25S. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1_supplement.21s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Inoue T., Toyoshima K., Kikui M. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (idiopathic BOOP) in childhood. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996;22:67–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199607)22:1<67::AID-PPUL9>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nishimura K., Itoh H. High-resolution computed tomographic features of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Chest. 1992;102:26S–31S. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1_supplement.26s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muller N.L., Staples C.A., Miller R.R. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: CT features in 14 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:983–987. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.5.2108572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bouchardy L.M., Kuhlman J.E., Ball W.C., Hruban R.H., Askin F.B., Siegelman S.S. CT findings in bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) with radiographic, clinical, and histologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:352–357. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chandler P.W., Shin M.S., Friedman S.E., Myers J.L., Katzenstein A.L. Radiographic manifestations of bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia versus usual interstitial pneumonia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:899–906. doi: 10.2214/ajr.147.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Muller N.L., Guerry-Force M.L., Staples C.A., Wright J.L., Wiggs B., Coppin C. Differential diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia and usual interstitial pneumonia: clinical, functional, and radiologic findings. Radiology. 1987;162:151–156. doi: 10.1148/radiology.162.1.3786754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee J.S., Lynch D.A., Sharma S., Brown K.K., Muller N.L. Organizing pneumonia: prognostic implication of high-resolution computed tomography features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:260–265. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200303000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Preidler K.W., Szolar D.M., Moelleken S., Tripp R., Schreyer H. Distribution pattern of computed tomography findings in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 1996;31:251–255. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee K.S., Kullnig P., Hartman T.E., Müller N.L. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: CT findings in 43 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:543–546. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.3.8109493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oikonomou A., Hansell D.M. Organizing pneumonia: the many morphological faces. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1486–1496. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Akira M., Yamamoto S., Sakatani M. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia manifesting as multiple large nodules or masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:291–295. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Johkoh T., Muller N.L., Cartier Y., Kavanagh P.V., Hartman T.E., Akira M. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: diagnostic accuracy of thin-section CT in 129 patients. Radiology. 1999;211:555–560. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma01555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thivolet F., Loire R., Cordier J.F. Bronchiolitis with peribronchiolar organizing pneumonia (B-POP): a new clinicopathologic entity in bronchiolar/interstitial lung disease? Eur Respir J. 1999;14(Suppl 30):272s. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murphy J.M., Schnyder P., Verschakelen J., Leuenberger P., Flower C.D. Linear opacities on HRCT in bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1813–1817. doi: 10.1007/s003300050928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Voloudaki A.E., Bouros D.E., Froudarakis M.E., Datseris G.E., Apostolaki E.G., Gourtsoyiannis N.C. Crescentic and ring-shaped opacities: CT features in two cases of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) Acta Radiol. 1996;37:889–892. doi: 10.1177/02841851960373P289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim S.J., Lee K.S., Ryu Y.H., Yoon Y.C., Choe K.O., Kim T.S. Reversed halo sign on high-resolution CT of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: diagnostic implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1251–1254. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.5.1801251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zompatori M., Poletti V., Battista G., Diegoli M. Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP), presenting as a ring-shaped opacity at HRCT (the atoll sign): a case report. Radiol Med. 1999;97:308–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Costabel U., Teschler H., Guzman J. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP): the cytological and immunocytological profile of bronchoalveolar lavage. Eur Respir J. 1992;5:791–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nagai S., Aung H., Tanaka S., Satake N., Mio T., Kawatani A. Bronchoalveolar lavage cell findings in patients with BOOP and related diseases. Chest. 1992;102:32S–37S. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.1_supplement.32s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Poletti V., Cazzato S., Minicuci N., Zompatori M., Burzi M., Schiattone M.L. The diagnostic value of bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2513–2516. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Naccache J.M., Wiesendanger T., Loire R., Cordier J.F. Hypoxemia due to right-to-left shunt in BOOP. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(Suppl 30):228s. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Naccache J.M., Faure O., Loire R., Wiesendanger T., Cordier J.F. Hypoxémie sévère avec orthodéoxie par shunt droit-gauche au cours d'une bronchiolite oblitérante avec organisation pneumonique idiopathique. [Severe hypoxemia with orthodeoxia due to right to left shunt in idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia] Rev Mal Respir. 2000;17:113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Epler G.R. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:158–164. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wells A.U. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22:449–459. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital: case 14–2003. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1902–1912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc030009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Perez de Llano L.A., Soilan J.L., Garcia Pais M.J., Mata I., Moreda M., Laserna B. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia presenting with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Med. 1998;92:884–886. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schwarz M.I. Diffuse pulmonary infiltrates and respiratory failure following 2 weeks of dyspnea in a 45-year-old woman. Chest. 1993;104:927–929. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.3.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nizami I.Y., Kissner D.G., Visscher D.W., Dubaybo B.A. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia: an acute and life-threatening syndrome. Chest. 1995;108:271–277. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Herridge M.S., Cheung A.M., Tansey C.M., Matte-Martyn A., Diaz-Granados N., Al-Saidi F. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Patel S.R., Karmpaliotis D., Ayas N.T., Mark E.J., Wain J., Thompson B.T. The role of open-lung biopsy in ARDS. Chest. 2004;125:197–202. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Koinuma D., Miki M., Ebina M., Tahara M., Hagiwara K., Kondo T. Successful treatment of a case with rapidly progressive bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) using cyclosporin A and corticosteroid. Intern Med. 2002;41:26–29. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Purcell I.F., Bourke S.J., Marshall S.M. Cyclophosphamide in severe steroid-resistant bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Respir Med. 1997;91:175–177. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cohen A.J., King T.E., Downey G.P. Rapidly progressive bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1670–1675. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Iannuzzi M.C., Farhi D.C., Bostrom P.D., Petty T.L., Fisher J.H. Fulminant respiratory failure and death in a patient with idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:733–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yousem S.A., Lohr R.H., Colby T.V. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia/cryptogenic organizing pneumonia with unfavorable outcome: pathologic predictors. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:864–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tomashefski J.F. Pulmonary pathology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2000;21:435–466. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wong K.T., Antonio G.E., Hui D.S., Lee N., Yuen E.H., Wu A. Thin-section CT of severe acute respiratory syndrome: evaluation of 73 patients exposed to or with the disease. Radiology. 2003;228:395–400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2283030541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bonaccorsi A., Cancellieri A., Chilosi M., Trisolini R., Boaron M., Crimi N. Acute interstitial pneumonia: report of a series. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:187–191. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00297002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ichikado K., Johkoh T., Ikezoe J., Yoshida S., Honda O., Mihara N. A case of acute interstitial pneumonia indistinguishable from bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia/cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: high-resolution CT findings and pathologic correlation. Radiat Med. 1998;16:367–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Beasley M.B., Franks T.J., Galvin J.R., Gochuico B., Travis W.D. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:1064–1070. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-1064-AFAOP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yoshinouchi T., Ohtsuki Y., Kubo K., Shikata Y. Clinicopathological study on two types of cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis. Respir Med. 1995;89:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0954-6111(95)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]