Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemics have affected populations in many countries, including Hong Kong. This disease is infectious, especially in hospital settings. Health care workers have expressed great concern, including those working in obstetrics wards, defined as high-risk areas.

Method

Four weeks after implementation of universal precautionary measures at a teaching hospital in Hong Kong, a survey of the health care staff was conducted to identify their feelings and opinions.

Results

In spite of general knowledge about SARS epidemics and related mortality, most respondents stated that universal precautionary measures were not very necessary, especially in the obstetrics ward. In addition, respondents were generally dissatisfied with the measures, as most items imposed extra work, inconvenience, and burdens on the staff.

Conclusion

Our findings reported the views and satisfaction levels of the front-line staff of an obstetric unit concerning precautionary measures against SARS. The importance of individualized design and implementation of infection control measures is highlighted and discussed.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemics affect populations in many countries, in both hospital and community settings. Caused by coronavirus and spread by droplet transmission,1., 2., 3., 4., 5. this disease and its high mortality rate have increased the psychological stress of all health care staff.4 Various precautionary measures have been suggested. Universal precautionary measures were believed to be necessary, especially in certain high-risk areas such as obstetrics wards, where contact with body fluid is common. Health care workers demanded personal protective equipment (PPE). The labor ward and obstetrics operating theater of Queen Mary Hospital, which is a tertiary center, adopted universal precautions in May 2003. Previously, only surgical gowning, single gloving, paper cap, surgical face mask, and boots were worn in the delivery room. Since early May 2003, universal precautionary measures were implemented and changes in PPE are shown in Table 1 . Understandably, such measures would impose extra work, inconvenience, and burdens to the staff, and might hinder the effective and efficient execution of their work. A simple questionnaire survey was conducted 4 weeks after the implementation of the universal precautionary measures. Our objectives are to present the views of our front-line staff, and to discuss universal precaution measures in obstetrics.

Table 1.

Personal protective equipment for universal precautions

| Labor ward (usual nursing care) | Labor ward (delivery) | Operating theater | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paper cap | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mask | |||

| Surgical mask | ✓ | ||

| N95 mask | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Face protection | |||

| Face shield | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Eye shield | ✓ | ||

| Goggle | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Paper hood | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Gown | |||

| Double gowning (plastic gown plus sterile surgical gown) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Plastic apron | ✓ | ||

| Double gloving | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Boot | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Method

An anonymous survey comprised of 5-point, Likert-scale items was conducted in early June 2003. Medical staff (obstetricians), nursing staff, medical students, and supporting staff working in the labor ward and the obstetrics operating theater were asked about the necessity for and their satisfaction with each of the universal precautionary measures. Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS for PCs, Version 11.5 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). Bivariate correlation procedures and one-way analysis of variance tests were used, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

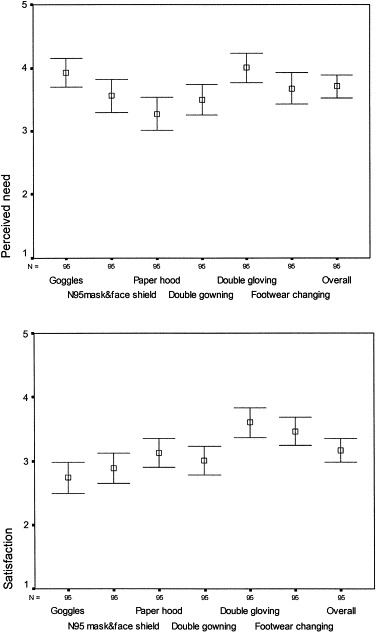

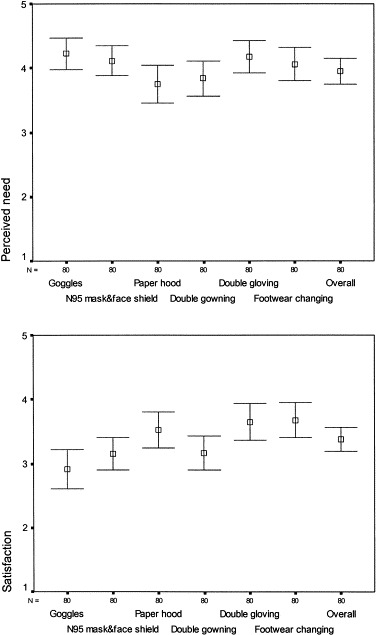

A total of 109 questionnaires were distributed 4 weeks after implementation of universal precautionary measures. Ninety-six questionnaires were returned (88%). The demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 2 . The respondents' opinions are summarized in Fig 1, Fig 2 . Most staff were quite neutral toward the necessity of the preventive measures in labor ward. On the other hand, they indicated that these measures are more necessary in the operating theater. Goggles and double gloving were perceived as the most necessary PPE items.

Table 2.

Demographic data

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Position | |

| Midwives | 46 (47.9) |

| Interns | 12 (12.5) |

| Obstetric staff | 15 (15.6) |

| Medical students | 16 (16.7) |

| Supporting staff | 7 (7.3) |

| Experience | |

| <5 years | 34 (35.4) |

| 5—10 years | 17 (17.8) |

| >10 years | 45 (46.9) |

| Current marital status | |

| Married | 35 (33.6) |

| Unmarried | 61 (66.4) |

| Living with children | |

| Yes | 35 (33.6) |

| No | 61 (66.4) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 72 (75) |

| Male | 24 (25) |

Fig 1.

Perceived need and satisfaction, labor ward staff (score with 95% confidence interval).

Fig 2.

Perceived need and satisfaction, obstetrics operating theater staff (score with 95% confidence interval).

Most staff were neutral or even unhappy about the precautionary measures. In particular, goggles were the least-welcome item, although they were believed to be necessary. Relationships between various demographic factors and the overall assessment rating were also investigated. The only statistically significant differences found pertained to occupation (P = 0.001) and gender (P = 0.034) regarding the necessity of the overall arrangement of universal precautions. Support staff and midwives found such preventive measures more necessary, and obstetricians found them much less necessary. Women held a more positive perception concerning the necessity of these measures. These results are congruent, as all midwives and most support staff in our unit are women.

Discussion

Ratings on the necessity of PPE were unexpectedly the lowest among the medical staff who should be in the closest contact with women in delivery. On the other hand, the support staff who clean the rooms believed that universal precautions were necessary. A number of explanations could be offered for this difference. First, our clinical staff may have been subconsciously assured that contact with SARS patients in the obstetric unit would be most unlikely, since obstetrics patients are mostly afebrile without any respiratory symptoms. The support staff does not have this knowledge. Second, the PPE hindered the efficient care of pregnant women. Goggles, eye shields, and multilayered protective clothing distort visual acuity and induce intense perspiration in the medical/nursing staff who had to be with women in labor for many hours. In contrast, the support staff only had to wear the PPE when they cleaned a room, which usually took less than 15 minutes. Visual distortion and heat generated by the PPE then would not be as problematic for support staff, who stated that they felt they were being protected more than peers on other wards. Third, medical/nursing staff were already accustomed to some form of protective clothing during their daily activities in the ward and operating theater. They might already feel protected from contamination by patients. Additional PPE might then be considered superfluous, depending on the area they worked in and their specific duties. Satisfaction levels with PPE were lower among labor ward staff than among operating theater staff, who were more accustomed to full infection protection. The occupational specialty mindset was very important, not only in terms of satisfaction with universal precautions, but also effective implementation.

It is worthwhile noting that there were some discrepancies between perceived need and satisfaction with individual protective equipment. This discrepancy seems to be related to the comfort of the equipment. Goggles were deemed to be needed, but they were tight, foggy, and reduced visual acuity; hence, the low satisfaction rate. Paper hoods are comfortable, and hence respondents indicated a high satisfaction rate, but were not rated as highly necessary since head hair were not considered to be a transmission site. Gloving, gowning, and footwear were more consistent in levels of need and satisfaction. These have been the usual PPE that staff are accustomed to.

This was a small study that aimed at appraising the effects on staff of universal precautions against SARS. It was not meant to produce figures reaching high levels of statistical power. Our findings should be important for health care managers to reassess the concept of universal precaution, and where and how it should be instituted. Unless this is done, universal precautions will not be implemented effectively, staff will not be protected, and managers will have a false sense of security.

SARS is an elusive and frightening infectious disease. It is obvious that there is an immense need for protection of all health care workers, including support staff. Our experience of universal precautionary measures in an obstetrics unit may start the discussion on the best precautions for particular health care staff in specific work environments.

Hong Kong, China

References

- 1.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seto W.H., Tsang D., Yung R.W., Ching T.Y., Ng T.K., Ho M. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Lancet. 2003;361:1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley S., Fraser C., Donnelly C.A. Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions. Science. 2003;300:1961–1966. doi: 10.1126/science.1086478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maunder R., Hunter J., Vincent L., Bennett J., Peladeau N., Leszcz M. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dwosh H.A., Hong H.H., Austgarden D., Herman S., Schabas R. Identification and containment of an outbreak of SARS in a community hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1415–1420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]