Abstract

Background

A total of 238 cases of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) occurred in Singapore between February 25 and May 11, 2003. Control relied on empirical methods to detect early and isolate all cases and quarantine those who were exposed to prevent spread in the community.

Methods

On April 28, 2003, the Infectious Diseases Act was amended in Parliament to strengthen the legal provisions for serving the Home Quarantine Order (HQO). In mounting large-scale quarantine operations, a framework for contact tracing, serving quarantine orders, surveillance, enforcement, health education, transport, and financial support was developed and urgently put in place.

Results

A total of 7863 contacts of SARS cases were served with an HQO, giving a ratio of 38 contacts per case. Most of those served complied well with quarantine; 26 (0.03%) who broke quarantine were penalized.

Conclusion

Singapore's experience underscored the importance of being prepared to respond to challenges with extraordinary measures. With emerging diseases, health authorities need to rethink the value of quarantine to reduce opportunities for spread from potential reservoirs of infection.

On May 31, 2003, Singapore was declared by the World Health Organization to be taken off the list of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-affected countries.1 Between February 25 and May 11, 2003, the city state had identified and treated a total of 238 cases, of whom 33 (14%) died. SARS was imported into Singapore through 3 unsuspecting young travelers returning from Hong Kong and immediately threatened to establish itself within hospitals.2, 3, 4 Measures by the Ministry of Health (MOH) to control the outbreak focused on 3 fronts5: (1) Proper triage of fever patients; mandatory protective gear and infection control procedures; close monitoring of health care workers for symptoms; and restrictions on movement of the health care workers, patients, and visitors were introduced in the hospitals. (2) Incoming and outgoing passengers were subject to thermal screening and health declarations at the border checkpoints. (3) Temperature taking, public education, and social responsibility for hygiene were emphasized in the community. It took 11 weeks before the chain of transmission was finally broken. The 2 main strategies were early detection and isolation of all cases and quarantine of all close contacts of symptomatic cases to prevent spread in the community. In implementing the large-scale public health operations, issues involving contact tracing, legal provisions and types of quarantine, choice of quarantine locations, surveillance, enforcement, educational home visits, ambulance transport, and financial support had to be addressed and systems urgently put in place. We report herein Singapore's experience with quarantine management in the control of SARS.

Materials and methods

Contact tracing

A contact tracing center was established over 48 hours in MOH with provision for 200 officers at its peak to undertake rapid and comprehensive identification of all contacts of SARS cases and observation cases in whom SARS could not be ruled out. The components of contact tracing included the following: obtaining all patient movements during the symptomatic stage; identifying the persons who had contact with the patient during these movements; and instituting follow-up action on the contacts for a 10-day period. A trigger board chaired by the Director of Medical Services decided on the classification and priority of each notified case. The triggers to activate contact tracing covered a broad spectrum of possibilities and included the following: all probable and suspect cases; cases of atypical pneumonia pending confirmation; fever >38°C with travel history to SARS-affected area; cluster of fever cases in a health care or step-down facility; unexplained fevers; death because of pneumonia without identifiable cause; and postmortem findings of respiratory distress syndrome.

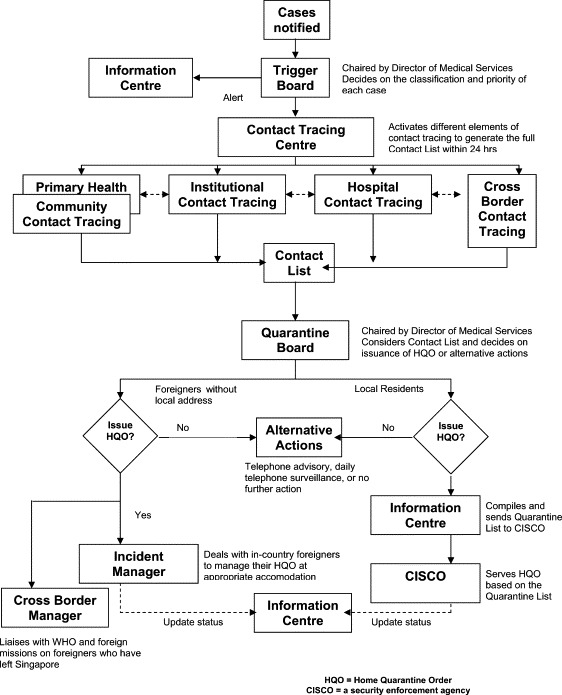

Contacts were defined as health care workers who did not use personal protective equipment while managing a SARS case; household members, including persons who worked or lived with a SARS case; visitors and patients exposed in a medical facility; persons who worked or shared recreation in the same premises as a SARS case; classmates or teachers of a SARS case; and persons who used the same conveyance as a SARS case with more than passing exposure. As challenges to contact tracing arose in health care settings, airline flights, cruise vessels, large educational institutions, hostels, factories, markets, food centers, places of worship, public buildings, and a mental hospital, our experience underscored the importance of maintaining a high level of vigilance and the preparedness to act and adjust strategies. Based on the lessons learned, policies were periodically modified to reduce the numbers that truly warranted monitoring without compromising public health (eg, from initial entire planeloads of passengers, contacts were later limited to those seated in physical proximity to the index patient).6 Inherent in the contact tracing operation was the assurance of health checks and careful follow-up of all identified contacts. The management workflow for contact tracing is shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Management workflow for contact tracing.

Legal provisions for quarantine

Although the legal basis for quarantine had been in place with the Infectious Diseases Act since 1976, it was never used until the SARS outbreak. Even then, for the first few close contacts of SARS cases, MOH only provided a health advisory document to alert the contacts that they had been exposed to SARS and what they should/should not do for 2 weeks following exposure. On March 24, 2003, when MOH invoked the Infectious Diseases Act to impose quarantine on persons who had been exposed to SARS and were potentially infectious, the provisions were found to be inadequate because it was not an offence for persons to break quarantine. The Act merely stipulated that, if a person should do so, he/she would be placed under isolation in a hospital or in any other suitable place, and it would only be an offence if the person escaped from such isolation. The Act also did not provide the legal powers to order the quarantine for those who have been treated for SARS or suspected SARS after their discharge from hospital.

On April 28, 2003, Parliament amended the Infectious Diseases Act to strengthen the legal provisions for quarantine. With the revisions, the Director of Medial Services could order the quarantine of any person who is or suspected to be or continues to be suspected to be a case or carrier or contact of an infectious disease or who has recovered from or been treated for such disease to remain and to be isolated in his dwelling place for a period as may be necessary for the protection of the public. Persons found guilty of breaking quarantine may be prosecuted and (1), in the case of a first offence, be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding $10,000 (Singapore dollars) or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months or to both and (2), in the case of a second or subsequent offence, be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding $20,000 (Singapore dollars) or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months or to both.

Types of quarantine order

The Director of Medical Services, assisted by a quarantine board, decided on the merits for quarantine in each case based on contact history and epidemiologic findings. The order signed by the director was known as the Home Quarantine Order (HQO), of which there were 3 types: (1) HQO for contacts of probable cases of SARS: This was served on all who had come in contact with a probable SARS patient. These contacts were placed on HQO for a period of 10 days from the date of last exposure to the SARS patient. The HQO document underwent several modifications to reflect developments that included the use of electronic picture cameras and tagging, an HQO allowance, and the listing of the particulars of children living in the same household who also had to be under quarantine. (2) HQO for probable and suspected SARS cases who were admitted to Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH)/Communicable Disease Centre (CDC), the designated SARS hospital, upon their discharge: All those who were treated for SARS or admitted for suspect SARS were required to be placed on HQO for a further 10 days after discharge. This was because little was known about the period of infectivity and whether the SARS patient was infectious during the convalescent phase of illness. There were additional concerns of whether a suspect case could have been infected with SARS without the typical clinical manifestations and of whether the patients would suffer a relapse upon discharge. (3) HQO for patients in Singapore General Hospital (SGH) and TTSH who have concomitant chronic diseases, upon their discharge: Patients with certain concurrent medical conditions were also placed on HQO for a period of 10 days following discharge from hospital. This followed realization that patients with chronic illnesses such as diabetes or heart failure and patients who were immunosuppressed because of cancer or steroid therapy could be sources of SARS without showing the typical signs and symptoms.

The Director of Medical Services also issued another order known as the Quarantine Order (QO), albeit in much low numbers. There were 2 types: (1) QO for probable and suspect SARS cases who were admitted to TTSH/CDC: All persons who were admitted to TTSH/CDC for probable/suspect SARS were served a QO to require them to remain under quarantine in the hospital until they were fit for discharge, and (2) QO for contacts of SARS cases among the SGH patients and staff who were exposed to SARS and were transferred to TTSH/CDC for further management: This was served on the patients and staff of SGH who were exposed to SARS and transferred to TTSH/CDC for further management. They were technically contacts, not SARS cases or suspect cases, required to stay under quarantine in TTSH/CDC.

Choice of quarantine location

Persons served with HQO were offered a choice of quarantine at home or at a specially prepared quarantine center, a temporary home. Individuals who were independent and capable of caring for themselves could be housed at the quarantine centers. Children, defined as those less than 18 years of age, had to be accompanied by an adult. Travelers to Singapore served with the HQO were also offered 2 options. First, they could choose to leave Singapore within 24 hours on receipt of HQO so long as they were afebrile. A travel advisory would be issued to them and the respective embassies informed that their national had been in contact with a SARS case in Singapore. Alternatively, the traveler could choose to remain in Singapore at a designated quarantine center.

Enforcement and surveillance

Enforcement and surveillance was outsourced to a security agency known as CISCO on April 10, 2003, because MOH resources were inadequate to handle the large numbers of HQOs. With this arrangement, auxiliary police officers replaced health officers in serving the HQO at the homes of the identified contacts. The quarantined persons were required to stay home throughout the 10-day period, monitor temperature twice daily and check for symptoms, and provide information fully and truthfully when required via telephone. Children staying in the same household were disallowed from attending school during this period. CISCO officers made random checks and called the contacts between 8 am and 11 pm daily to ensure that they were at home. There were instances when such persons diverted the home telephone number to their hand telephone to give an impression of compliance. Consequently, surveillance was tightened by installing an electronic picture camera in each home. These cameras were normally switched off to maintain privacy but, when called, the person had to turn on the camera and present himself in front of it to show that he/she was really at home.

Home visit and ambulance transport

To soften the stressful impact of enforcement measures, MOH's Health Promotion Board (HPB) nurses carried out concurrent educational home visits to every affected household. During these visits, those on HQO were each given a home quarantine kit, which included an oral thermometer and an N95 mask. The nurse would explain the way SARS was transmitted, the rationale for their quarantine, and conditions in the HQO that they had to observe. They were also taught good personal hygiene practices, how to chart their temperature twice daily, and measures to minimize contact with other family members and instructed to report to the hospital if ill.

A 24-hour dedicated ambulance service (993 hotline number) was provided by MOH to bring anyone with fever or other symptoms to the hospital immediately. The transport was offered free of charge for all ill persons, going direct from home to the TTSH/CDC for medical evaluation and treatment. The quarantined persons were strongly cautioned to refrain from using the public transport system to get to hospital, and, in this way, the public transport system was safeguarded.

Financial supports

Under an HQO allowance scheme administered by 5 Community Development Councils, the government undertook to pay to self-employed persons an allowance of approximately U.S. $41 per day for the duration of the quarantine period to make up part of their lost income while on quarantine. The scheme also gave the allowance to small business establishments (employing 50 or fewer persons) that were ordered to close temporarily because of SARS. Employees on HQO were deemed to be under hospitalization leave, and their employers were reimbursed the actual salary of their employees up to a maximum of U.S. $41 per day. With this scheme in place, the government took on the burden of a good part of the wage cost of eligible employees.

Results

A total of 7863 contacts who had been exposed to 206 probable cases of SARS were served with an HQO, giving a ratio of 38 contacts per case. The age distribution and contact history of the SARS cases and quarantined persons are shown in Table 1, Table 2, respectively. No HQOs were served on the contacts of 32 probable cases who were subsequently diagnosed by laboratory tests because the incubation period had lapsed. Those under HQO belonged to 5072 households, giving a ratio of 25 affected households per case. In 163 of the households, all the members had to be served with an HQO. An additional 4331 contacts were not quarantined but put on daily telephone surveillance for 10 days as a precaution. In total, 58 of the SARS cases had been among the 12,194 persons on either HQO or telephone surveillance prior to their diagnosis, giving a yield of 0.48%.

Table 1.

Age distribution and contact history of 238 SARS cases in Singapore, March-May 2003

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (y) | ||

| 0-4 | 5 | 2.1 |

| 5-14 | 5 | 2.1 |

| 15-24 | 37 | 15.5 |

| 25-34 | 66 | 27.8 |

| 35-44 | 45 | 18.9 |

| 45-54 | 33 | 13.9 |

| 55-64 | 25 | 10.5 |

| 65+ | 22 | 9.2 |

| Contact history | ||

| Overseas | 8 | 3.4 |

| Health care | 128 | 53.8 |

| Household | 55 | 23.1 |

| Friend/social | 35 | 14.7 |

| Workplace∗ | 6 | 2.5 |

| Others (undefined) | 6 | 2.5 |

| Total | 238 | 100 |

Three market workers, 2 taxi drivers, 1 flight stewardess.

Table 2.

Age distribution and contact history of 7863 quarantined persons in Singapore, March-May 2003

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (y) | ||

| 0-4 | 116 | 1.5 |

| 5-14 | 211 | 2.7 |

| 15-24 | 594 | 7.6 |

| 25-34 | 1000 | 12.7 |

| 35-44 | 1177 | 15.0 |

| 45-54 | 1274 | 16.2 |

| 55-64 | 882 | 11.2 |

| 65+ | 1159 | 14.7 |

| Unspecified | 1450 | 18.4 |

| Contact history | ||

| Health care | 1555 | 19.8 |

| Household | 876 | 11.1 |

| Friend/social | 208 | 2.6 |

| Workplace/school | 2326 | 29.6 |

| Others∗ | 2898 | 36.9 |

| Total | 7863 | 100 |

Includes airline flight passengers; hostelites; and visitors to markets, food centers, places of worship, and public buildings.

Most of the 7863 persons served with an HQO understood and complied well with quarantine. Of those, 194 (2.5%) activated the 993 ambulance service to seek medical consultation at the TTSH/CDC. However, another 26 (0.3%) persons broke their quarantine for invalid or frivolous reasons. As a deterrent, the Subordinate Court sentenced 1 offender to 6 months imprisonment for violating his HQO on multiple occasions and flaunting the fact that he had violated his HQO. Another 2 offenders were detained in an isolation facility to serve the remaining of their HQO period for violating their HQO on at least 3 occasions. The rest were first-time offenders who strictly observed their HQO after being issued a warning letter and an electronic wrist tag. The tag was linked to a telephone line and would alert the authorities immediately if the quarantined person tried to leave the house again or break the tag.

The bulk of the costs to mount the large-scale quarantine operations during the SARS outbreak was the U.S. $3 million incurred by MOH in engaging CISCO between April and July 2003 as the provider of goods and services to administer and enforce HQOs ( Table 3). Payouts of the HQO allowance scheme amounted to U.S. $1.8 million, and another U.S. $0.4 million was incurred providing the 993 call center and ambulance services. Not counted but related to the conduct of quarantine operations were the contact tracing and home visits that were carried out by MOH and other agencies using internal resources. Similarly, because most people served quarantine within their own home, they assumed the cost of quarantine housing.

Table 3.

Services and costs for large-scale quarantine operations during the SARS outbreak in Singapore, 2003

| Services | Cost (US millions) |

|---|---|

| Enforcement and surveillance operations | $1.9 |

| Setup of dedicated quarantine command center | $0.4 |

| Purchase and use of 2110 electronic picture cameras | $0.7 |

| Payouts of the HQO allowance scheme | $1.8 |

| Provision of 993 call center and ambulance services | $0.4 |

| Total | $5.2 |

Discussion

Quarantine is the separation and/or restriction of movement of persons who are not ill but, because of recent exposure, are suspected to be carrying an infection. The aim is to prevent exposure and transmission to others, and the period of time is not longer than the longest incubation period of the disease. The emergence of a novel disease provided the unique opportunity to test the implementation of contact tracing and quarantine to effect disease containment.7 The decision to undertake these measures was not based on scientific evidence of the merits of quarantine but on an urgent need to protect the community from a serious new disease that carried a high case fatality of 14%. The absence of effective vaccination and antiviral treatment strengthened the argument that quarantine management was necessary to stop the spread of this dangerous disease.

The main lesson to learn from the SARS outbreak is the capability of an emerging infection to cause a pandemic in a short span of time and the paradigm shift needed to respond to such a disease. Our experience of mounting large-scale quarantine operations confirmed the necessity of having proper systems in place within an organizational framework for resources to be deployed effectively. Once the framework was established, the logistics of large-scale quarantine became doable. Nonetheless, given the commitment of resources, other disease investigation routines and health promotion activities had to be placed on hold or delayed. The public health operations were successful because it was possible to define the persons who were exposed to a symptomatic SARS case and hence at risk of spreading the disease. Those quarantined were also agreeable to being confined at home. Health education by visiting nurses, rigorous electronic surveillance, and financial incentives probably contributed to the low rate of 0.3% noncompliance with quarantine. There were many legal and operational obstacles that had to be overcome, but the government showed determination by committing the necessary resources to make quarantine action work.

The contact tracing exercise between March and May 2003 cast a wide net through comprehensive identification of contacts to increase the sensitivity of control. Identification, on average, of 38 contacts per case showed a tendency toward error on the side of caution. This strategy worked because, by reducing many of the potential reservoirs of infection, opportunities for the virus to spread in the community remained rare and the outbreak was limited very much to nosocomial (health care setting) and intrahousehold infection. On the other hand, the same strategy resulted in quarantining large numbers of people who eventually turned out not to have SARS, giving a very low yield of under 0.5%. This was similar to the experience in other countries and suggests that efficiency could be improved greatly in future outbreaks by improving the specificity of criteria used in defining the contacts for quarantine.8, 9

Despite social education and financial support by the government, some who were quarantined reported problems associated with stigmatization by their neighbors. Research is required in this important area to weigh the benefits of large-scale quarantine actions against the adverse consequences. Countries that instituted quarantine during the SARS outbreak justified it on the grounds that even 1 missed case might have catastrophic consequences in a super-spreading event. SARS was not just a public health crisis but also a crisis of confidence in good government. Quarantine of the contacts of a SARS case gave members of the public confidence to continue with their normal daily business in the knowledge that public health safeguards existed. Otherwise, they would probably take actions to avoid public places and cause a paradoxical situation in which the unaffected majority stayed at home instead of the affected minority.

In conclusion, Singapore's experience underscored the importance of being prepared to respond to challenges with extraordinary measures. To improve the yield for quarantine, we need to refine the criteria as to which contacts constituted higher risk and should be served the HQO. Imposition of large-scale quarantine should be implemented only under specific situations in which it is legally and logistically feasible. With the increasing threat of emerging infections and bioterrorism, public health authorities need to rethink the value of quarantine management as a tool for disease control.

Acknowledgments

The authors dedicate this article with thanks to all our public health officers and executives, who were heavily involved in the contact tracing and quarantine operations during the SARS outbreak. Without their selfless contributions, the outbreak would have been much worse for Singapore.

Singapore

References

- 1.World Health Organization, 2003, Update 70–Singapore removed from list of areas with local SARS transmission. May 30. Available from: www.who.int/csr/don/2003_05_30a/en/. Accessed December 9, 2004.

- 2.Hsu L.Y., Lee C.C., Green J.A., Ang B., Paton N.I., Lee L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Singapore: clinical features of the index patient and initial contacts. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:713–717. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leo Y.S., Chen M., Heng B.H., Paton N., Ang B., Choo P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Singapore, 2003. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopalakrishna G., Choo P., Leo Y.S., Tay B.K., Lim Y.T., Khan A.S. SARS transmission and hospital containment. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:395–400. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.030650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ooi PL, Lim S, Tham KW. SARS and the city: emerging health concerns in the built environment. In: Tham KW, Chandra S, Cheong D, editors. Proceedings 7th International Conference Health Buildings 2003. Singapore: National University of Singapore; 2003. p. 73-80.

- 6.Olsen S.J., Chang H., Cheung T.Y., Tang A.F., Fisk T.L., Ooi P.L. Transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome on aircraft. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2416–2422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbera J., Macintyre A., Gostin L., Inglesby T., O'Toole T., DeAtley C. Large-scale quarantine following biological terrorism in the United States. JAMA. 2001;286:2711–2717. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee M.L., Chen C.J., Su I.J., Chen K.T., Yeh C.C., King C.C. Use of quarantine to prevent transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome–Taiwan. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:680–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ou J., Li Q., Zeng G., Dun Z., Qin A. Efficiency of quarantine during an epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome–Beijing, China, 2003. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1037–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]