Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC)

Chair

Patrick J. Brennan, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Pennsylvania Medical School

Executive Secretary

Michael Bell, MD, Division of Health Care Quality Promotion, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Members

Vicki L. Brinsko, RN, BA, Infection Control Coordinator, Vanderbilt University Medical Center

E. Patchen Dellinger, MD, Professor of Surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine

Jeffrey Engel, MD, Head, General Communicable Disease Control Branch, North Carolina State Epidemiologist

Steven M. Gordon, MD, Chairman, Department of Infections Diseases, Hospital Epidemiologist, Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Lizzie J. Harrell, PhD, D(ABMM), Research Professor of Molecular Genetics, Microbiology and Pathology, Associate Director, Clinical Microbiology, Duke University Medical Center

Carol O'Boyle, PhD, RN, Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota

David Alexander Pegues, MD, Division of Infectious Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Dennis M. Perrotta, PhD, CIC, Adjunct Associate Professor of Epidemiology, University of Texas School of Public Health, Texas A&M University School of Rural Public Health

Harriett M. Pitt, MS, CIC, RN, Director, Epidemiology, Long Beach Memorial Medical Center

Keith M. Ramsey, MD, Professor of Medicine, Medical Director of Infection Control, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University

Nalini Singh, MD, MPH, Professor of Pediatrics, Epidemiology and International Health, George Washington University Children's National Medical Center

Kurt Brown Stevenson, MD, MPH Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Ohio State University Medical Center

Philip W. Smith, MD, Chief, Section of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center

HICPAC membership (past)

Robert A. Weinstein, MD (Chair), Cook County Hospital, Chicago, IL

Jane D. Siegel, MD (Co-Chair), University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Michele L. Pearson, MD (Executive Secretary), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA

Raymond Y.W. Chinn, MD, Sharp Memorial Hospital, San Diego, CA

Alfred DeMaria, Jr, MD, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Jamaica Plain, MA

James T. Lee, MD, PhD, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

William A. Rutala, PhD, MPH, University of North Carolina Health Care System, Chapel Hill, NC

William E. Scheckler, MD, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI

Beth H. Stover, RN, Kosair Children's Hospital, Louisville, KY

Marjorie A. Underwood, RN, BSN CIC, Mt Diablo Medical Center, Concord, CA

HICPAC Liaisons

William B. Baine, MD, Liaison to the Agency for Health Care Quality Research

Joan Blanchard, RN, MSN, CNOR, Liaison to the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses

Patrick J. Brennan, MD, Liaison to the Board of Scientific Counselors

Nancy Bjerke, RN, MPH, CIC, Liaison to the Association of Professionals in Infection Prevention and Control

Jeffrey P. Engel, MD, Liaison to the Advisory Committee on Elimination of Tuberculosis

David Henderson, MD, Liaison to the National Institutes of Health

Lorine J. Jay, MPH, RN, CPHQ, Liaison to the Health Care Resources Services Administration

Stephen F. Jencks, MD, MPH, Liaison to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Sheila A. Murphey, MD, Liaison to the Food and Drug Administration

Mark Russi, MD, MPH, Liaison to the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine

Rachel L. Stricof, MPH, Liaison to the Advisory Committee on Elimination of Tuberculosis

Michael L. Tapper, MD, Liaison to the Society for Health Care Epidemiology of America

Robert A. Wise, MD, Liaison to the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Health Care Organizations

Authors' Associations

Jane D. Siegel, MD, Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Emily Rhinehart, RN, MPH, CIC, CPHQ, Vice President, AIG Consultants, Inc

Marguerite Jackson, RN, PhD, CIC, Director, Administrative Unit, National Tuberculosis Curriculum Consortium, Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego

Linda Chiarello, RN, MS, Division of Health Care Quality Promotion, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Table of contents

Executive Summary

Abbreviations

Part I: Review of the Scientific Data Regarding Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings

-

I.A.

Evolution of the 2007 Document

-

I.B.Rationale for Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions in Health Care Settings

-

I.B.1.Source of Infectious Agents

-

I.B.2.Susceptible Hosts

-

I.B.3.Modes of Transmission

-

I.B.3.a.Contact Transmission

-

I.B.3.a.i.Direct Contact Transmission

-

I.B.3.a.ii.Indirect Contact Transmission

-

I.B.3.a.i.

-

I.B.3.b.Droplet Transmission

-

I.B.3.c.Airborne Transmission

-

I.B.3.d.Emerging Issues and Controversies Concerning Bioaerosols and Airborne Transmission of Infectious Agents

-

I.B.3.d.i.Transmission From Patients

-

I.B.3.d.ii.Transmission From the Environment

-

I.B.3.d.i.

-

I.B.3.e.Other Sources of Infection

-

I.B.3.a.

-

I.B.1.

-

I.C.Infectious Agents of Special Infection Control Interest for Health Care Settings

-

I.C.1.Epidemiologically Important Organisms

-

I.C.1.a.Clostridium difficile

-

I.C.1.b.Multidrug-Resistant Organisms

-

I.C.1.a.

-

I.C.2.Agents of Bioterrorism

-

I.C.3.Prions

-

I.C.4.Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

-

I.C.5.Monkeypox

-

I.C.6.Noroviruses

-

I.C.7.Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses

-

I.C.1.

-

I.D.Transmission Risks Associated With Specific Types of Health Care Settings

-

I.D.1.Hospitals

-

I.D.1.a.Intensive Care Units

-

I.D.1.b.Burn Units

-

I.D.1.c.Pediatrics

-

I.D.1.a.

-

I.D.2.Nonacute Care Settings

-

I.D.2.a.Long-Term Care

-

I.D.2.b.Ambulatory Care

-

I.D.2.c.Home Care

-

I.D.2.d.Other Sites of Health Care Delivery

-

I.D.2.a.

-

I.D.1.

-

I.E.Transmission Risks Associated With Special Patient Populations

-

I.E.1.Immunocompromised Patients

-

I.E.2.Cystic Fibrosis Patients

-

I.E.1.

-

I.F.New Therapies With Potential Transmissible Infectious Agents

-

I.F.1.Gene Therapy

-

I.F.2.Infections Transmitted Through Blood, Organs and Tissues

-

I.F.3.Xenotransplantation and Tissue Allografts

-

I.F.1.

Part II. Fundamental Elements to Prevent Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings

-

II.A.Health Care System Components That Influence the Effectiveness of Precautions to Prevent Transmission

-

II.A.1.Administrative Measures

-

II.A.1.a.Scope of Work and Staffing Needs for Infection Control Professionals

-

II.A.1.a.i.Infection Control Liaison Nurse

-

II.A.1.a.i.

-

II.A.1.b.Bedside Nurse Staffing

-

II.A.1.c.Clinical Microbiology Laboratory Support

-

II.A.1.a.

-

II.A.2.Institutional Safety Culture and Organizational Characteristics

-

II.A.3.Adherence of Health Care Workers to Recommended Guidelines

-

II.A.1.

-

II.B.

Surveillance for Health Care–Associated Infections

-

II.C.

Education of Health Care Workers, Patients, and Families

-

II.D.

Hand Hygiene

-

II.E.Personal Protective Equipment for Health Care Workers

-

II.E.1.Gloves

-

II.E.2.Isolation Gowns

-

II.E.3.Face Protection: Masks, Goggles, Face Shields

-

II.E.3.a.Masks

-

II.E.3.b.Goggles and Face Shields

-

II.E.3.a.

-

II.E.4.Respiratory Protection

-

II.E.1.

-

II.F.Safe Work Practices to Prevent Health Care Worker Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens

-

II.F.1.Prevention of Needlesticks and Other Sharps-Related Injuries

-

II.F.2.Prevention of Mucous Membrane Contact

-

II.F.2.a.Precautions During Aerosol-Generating Procedures

-

II.F.2.a.

-

II.F.1.

-

II.G.Patient Placement

-

II.G.1.Hospitals and Long-Term Care Settings

-

II.G.2.Ambulatory Care Settings

-

II.G.3.Home Care

-

II.G.1.

-

II.H.

Transport of Patients

-

II.I.

Environmental Measures

-

II.J.

Patient Care Equipment, Instruments/Devices

-

II.K.

Textiles and Laundry

-

II.L.

Solid Waste

-

II.M.

Dishware and Eating Utensils

-

II.N.Adjunctive Measures

-

II.N.1.Chemoprophylaxis

-

II.N.2.Immunoprophylaxis

-

II.N.3.Management of Visitors

-

II.N.3.a.Visitors as Sources of Infection

-

II.N.3.b.Use of Barrier Precautions by Visitors

-

II.N.3.a.

-

II.N.1.

Part III. HICPAC Precautions to Prevent Transmission of Infectious Agents

-

III.A.Standard Precautions

-

III.A.1.New Standard Precautions for Patients

-

III.A.1.a.Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette

-

III.A.1.b.Safe Injection Practices

-

III.A.1.c.Infection Control Practices for Special Lumbar Puncture Procedures

-

III.A.1.a.

-

III.A.1.

-

III.B.Transmission-Based Precautions

-

III.B.1.Contact Precautions

-

III.B.2.Droplet Precautions

-

III.B.3.Airborne Infection Isolation Precautions

-

III.B.1.

-

III.C.

Syndromic or Empiric Application of Transmission-Based Precautions

-

III.D.

Discontinuation of Precautions

-

III.E.

Application of Transmission-Based Precautions in Ambulatory and Home Care Settings

-

III.F.

Protective Environment

Part IV: Recommendations

Appendix A: Type and Duration of Precautions Needed for Selected Infections and Conditions

Glossary

References

Table 1. Recent history of guidelines for prevention of health care–associated infections

Table 2. Clinical syndromes or conditions warranting additional empiric transmission-based precautions pending confirmation of diagnosis

Table 3. Infection control considerations for high-priority (CDC category A) diseases that may result from bioterrorist attacks or are considered bioterrorist threats

Table 4. Recommendations for application of Standard Precautions for the care of all patients in all health care settings

Table 5. Components of a protective environment

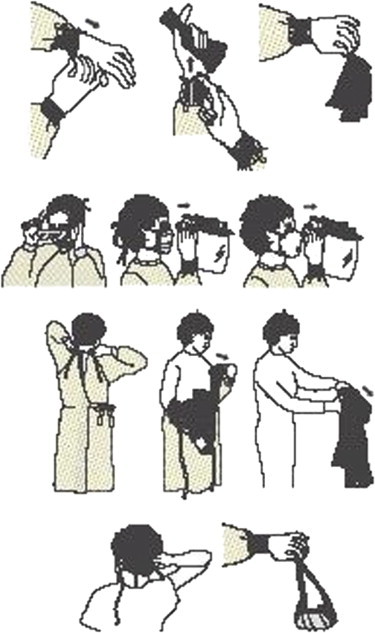

Fig 1. Sequence for donning and removing personal protective equipment

Executive Summary

The Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings 2007 updates and expands the 1996 Guideline for Isolation Precautions in Hospitals. The following developments led to these revisions of the 1996 guideline:

-

1.

The transition of health care delivery from primarily acute care hospitals to other health care settings (eg, home care, ambulatory care, free-standing specialty care sites, long-term care) created a need for recommendations that can be applied in all health care settings using common principles of infection control practice, yet can be modified to reflect setting-specific needs. Accordingly, the revised guideline addresses the spectrum of health care delivery settings. Furthermore, the term “nosocomial infections“ is replaced by “health care–associated infections” (HAIs), to reflect the changing patterns in health care delivery and difficulty in determining the geographic site of exposure to an infectious agent and/or acquisition of infection.

-

2.

The emergence of new pathogens (eg, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [SARS-CoV] associated with SARS avian influenza in humans), renewed concern for evolving known pathogens (eg, Clostridium difficile, noroviruses, community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [CA-MRSA]), development of new therapies (eg, gene therapy), and increasing concern for the threat of bioweapons attacks, necessitates addressing a broader scope of issues than in previous isolation guidelines.

-

3.

The successful experience with Standard Precautions, first recommended in the 1996 guideline, has led to a reaffirmation of this approach as the foundation for preventing transmission of infectious agents in all health care settings. New additions to the recommendations for Standard Precautions are respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette and safe injection practices, including the use of a mask when performing certain high-risk, prolonged procedures involving spinal canal punctures (eg, myelography, epidural anesthesia). The need for a recommendation for respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette grew out of observations during the SARS outbreaks, when failure to implement simple source control measures with patients, visitors, and health care workers (HCWs) with respiratory symptoms may have contributed to SARS-CoV transmission. The recommended practices have a strong evidence base. The continued occurrence of outbreaks of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses in ambulatory settings indicated a need to reiterate safe injection practice recommendations as part of Standard Precautions. The addition of a mask for certain spinal injections grew from recent evidence of an associated risk for developing meningitis caused by respiratory flora.

-

4.

The accumulated evidence that environmental controls decrease the risk of life-threatening fungal infections in the most severely immunocompromised patients (ie, those undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [HSCT]) led to the update on the components of the protective environment (PE).

-

5.

Evidence that organizational characteristics (eg, nurse staffing levels and composition, establishment of a safety culture) influence HCWs' adherence to recommended infection control practices, and thus are important factors in preventing transmission of infectious agents, led to a new emphasis and recommendations for administrative involvement in the development and support of infection control programs.

-

6.

Continued increase in the incidence of HAIs caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) in all health care settings and the expanded body of knowledge concerning prevention of transmission of MDROs created a need for more specific recommendations for surveillance and control of these pathogens that would be practical and effective in various types of health care settings.

This document is intended for use by infection control staff, health care epidemiologists, health care administrators, nurses, other health care providers, and persons responsible for developing, implementing, and evaluating infection control programs for health care settings across the continuum of care. The reader is referred to other guidelines and websites for more detailed information and for recommendations concerning specialized infection control problems.

Parts I, II, and III: Review of the Scientific Data Regarding Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings

Part I reviews the relevant scientific literature that supports the recommended prevention and control practices. As in the 1996 guideline, the modes and factors that influence transmission risks are described in detail. New to the section on transmission are discussions of bioaerosols and of how droplet and airborne transmission may contribute to infection transmission. This became a concern during the SARS outbreaks of 2003, when transmission associated with aerosol-generating procedures was observed. Also new is a definition of “epidemiologically important organisms” that was developed to assist in the identification of clusters of infections that require investigation (ie multidrug-resistant organisms, C difficile). Several other pathogens of special infection control interest (ie, norovirus, SARS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] category A bioterrorist agents, prions, monkeypox, and the hemorrhagic fever viruses) also are discussed, to present new information and infection control lessons learned from experience with these agents. This section of the guideline also presents information on infection risks associated with specific health care settings and patient populations.

Part II updates information on the basic principles of hand hygiene, barrier precautions, safe work practices, and isolation practices that were included in previous guidelines. However, new to this guideline is important information on health care system components that influence transmission risks, including those components under the influence of health care administrators. An important administrative priority that is described is the need for appropriate infection control staffing to meet the ever-expanding role of infection control professionals in the complex modern health care system. Evidence presented also demonstrates another administrative concern: the importance of nurse staffing levels, including ensuring numbers of appropriately trained nurses in intensive care units (ICUs) for preventing HAIs. The role of the clinical microbiology laboratory in supporting infection control is described, to emphasize the need for this service in health care facilities. Other factors that influence transmission risks are discussed, including the adherence of HCWs to recommended infection control practices, organizational safety culture or climate, and education and training.

Discussed for the first time in an isolation guideline is surveillance of health care–associated infections. The information presented will be useful to new infection control professionals as well as persons involved in designing or responding to state programs for public reporting of HAI rates.

Part III describes each of the categories of precautions developed by the Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) and the CDC and provides guidance for their application in various health care settings. The categories of Transmission-Based Precautions are unchanged from those in the 1996 guideline: Contact, Droplet, and Airborne. One important change is the recommendation to don the indicated personal protective equipment (PPE—gowns, gloves, mask) on entry into the patient's room for patients who are on Contact and/or Droplet Precautions, because the nature of the interaction with the patient cannot be predicted with certainty, and contaminated environmental surfaces are important sources for transmission of pathogens. In addition, the PE for patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, described in previous guidelines, has been updated.

Tables, Appendices, and Other Information

Five tables summarize important information. Table 1 provides a summary of the evolution of this document. Table 2 gives guidance on using empiric isolation precautions according to a clinical syndrome. Table 3 summarizes infection control recommendations for CDC category A agents of bioterrorism. Table 4 lists the components of Standard Precautions and recommendations for their application, and Table 5 lists components of the PE.

Table 1.

History of guidelines for isolation precautions in hospitals∗

| Year (reference) | Document issued | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 19701095 | Isolation Techniques for Use in Hospitals, 1st ed | • Introduced 7 isolation precaution categories with color-coded cards: strict, respiratory, protective, enteric, wound and skin, discharge, and blood. |

| • No user decision making required. | ||

| • Simplicity a strength; overisolation prescribed for some infections. | ||

| 19751100 | Isolation Techniques for Use in Hospitals, 2nd ed | • Same conceptual framework as first edition. |

| 19831096, 1097 | Guideline for Isolation Precautions in Hospitals | • Provided 2 systems for isolation: category-specific and disease-specific. |

| • Protective isolation eliminated; blood precautions expanded to include body fluids. | ||

| • Categories included strict, contact, respiratory, acid-fast bacteria, enteric, drainage/secretion, blood and body fluids. | ||

| • Emphasized decision making by users. | ||

| 1985-88778, 894 | Universal Precautions | • Developed in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. |

| • Dictated application of blood and body fluid precautions to all patients, regardless of infection status. | ||

| • Did not apply to feces, nasal secretions, sputum, sweat, tears, urine, or vomitus unless contaminated by visible blood. | ||

| • Added personal protective equipment to protect health care workers from mucous membrane exposures. | ||

| • Handwashing recommended immediately after glove removal. | ||

| • Added specific recommendations for handling needles and other sharp devices; concept became integral to the OSHA's 1991 rule on occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens in health care settings. | ||

| 19871098 | Body Substance Isolation | • Emphasized avoiding contact with all moist and potentially infectious body substances except sweat even if blood not present. |

| • Shared some features with Universal Precautions. | ||

| • Weak on infections transmitted by large droplets or by contact with dry surfaces. | ||

| • Did not emphasize need for special ventilation to contain airborne infections. | ||

| • Handwashing after glove removal not specified in the absence of visible soiling. | ||

| 19961 | Guideline for Isolation Precautions in Hospitals | • Prepared by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. |

| • Melded major features of Universal Precautions and body substance isolation into Standard Precautions to be used with all patients at all times. | ||

| • Included 3 transmission-based precaution categories: Airborne, Droplet, and Contact. | ||

| • Listed clinical syndromes that should dictate use of empiric isolation until an etiologic diagnosis is established. |

Derived from Garner and Simmons.1099

Table 2.

Clinical syndromes or conditions warranting empiric transmission-based precautions in addition to Standard Precautions pending confirmation of diagnosis∗

| Clinical syndrome or condition† | Potential pathogens‡ | Empiric precautions (always includes Standard Precautions) |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | ||

| Acute diarrhea with a likely infectious cause in an incontinent or diapered patient | Enteric pathogens§ | Contact Precautions (pediatrics and adult) |

| Meningitis | Neisseria meningitidis | Droplet Precautions for first 24 hours of antimicrobial therapy; mask and face protection for intubation |

| Enteroviruses | Contact Precautions for infants and children | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Airborne Precautions if pulmonary infiltrate present | |

| Airborne Precautions plus Contact Precautions if potentially infectious draining body fluid present | ||

| Rash or exanthems, generalized, etiology unknown | ||

| Petechial/ecchymotic with fever (general) | Neisseria meningitides | Droplet Precautions for the first 24 hours of antimicrobial therapy |

| Positive history of travel to an area with an ongoing outbreak of VHF in the 10 days before onset of fever | Ebola, Lassa, Marburg viruses | Droplet Precautions plus Contact Precautions, with face/eye protection, emphasizing safety sharps and Barrier Precautions when blood exposure likely. N95 or higher-level respiratory protection when aerosol-generating procedure performed |

| Vesicular | Varicella-zoster, herpes simplex, variola (smallpox), vaccinia viruses | Airborne plus Contact Precautions |

| Vaccinia virus | Contact Precautions only if herpes simplex, localized zoster in an immunocompetent host, or vaccinia virus likely | |

| Maculopapular with cough, coryza, and fever | Rubeola (measles) virus | Airborne Precautions |

| Respiratory infections | ||

| Cough/fever/upper lobe pulmonary infiltrate in an HIV-negative patient or a patient at low risk for HIV infection | M. tuberculosis, respiratory viruses, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA or MRSA) | Airborne Precautions plus Contact Precautions |

| Cough/fever/pulmonary infiltrate in any lung location in an HIV-infected patient or a patient at high risk for HIV infection | M tuberculosis, respiratory viruses, S pneumoniae, S aureus (MSSA or MRSA) | Airborne Precautions plus Contact Precautions; eye/face protection if aerosol-generating procedure performed or contact with respiratory secretions anticipated; Droplet Precautions instead of Airborne Precautions if tuberculosis unlikely and airborne infection isolation room and/or respirator unavailable (tuberculosis more likely in HIV-infected than in HIV-negative individuals) |

| Cough/fever/pulmonary infiltrate in any lung location in a patient with a history of recent travel (10 to 21 days) to countries with active outbreaks of SARS, avian influenza | M tuberculosis, severe acute respiratory syndrome virus (SARS-CoV), avian influenza | Airborne plus Contact Precautions plus eye protection; Droplet Precautions instead of Airborne Precautions if SARS and tuberculosis unlikely |

| Respiratory infections, particularly bronchiolitis and pneumonia, in infants and young children | Respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, influenza virus, human metapneumovirus | Contact plus Droplet Precautions; discontinue Droplet Precautions if adenovirus and influenza ruled out |

| Skin or wound infection | ||

| Abscess or draining wound that cannot be covered | S aureus (MSSA or MRSA), group A streptococcus | Contact Precautions, plus Droplet Precautions for the first 24 hours of appropriate antimicrobial therapy if invasive group A streptococcal disease suspected |

Infection control professionals should modify or adapt this table according to local conditions. To ensure that appropriate empiric precautions are implemented always, hospitals must have systems in place to evaluate patients routinely according to these criteria as part of their preadmission and admission care.

Patients with the syndromes or conditions listed below may present with atypical signs or symptoms (eg, neonates and adults with pertussis may not have paroxysmal or severe cough). The clinician's index of suspicion should be guided by the prevalence of specific conditions in the community, as well as clinical judgment.

The organisms listed under the column “Potential Pathogens” are not intended to represent the complete, or even most likely, diagnoses, but rather possible etiologic agents that require additional precautions beyond Standard Precautions until they can be ruled out.

These pathogens include enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7, Shigella spp, hepatitis A virus, noroviruses, rotavirus, and Clostridium difficile.

Table 3.

Infection control considerations for high-priority (CDC category A) diseases that may result from bioterrorist attacks or are considered bioterrorist threats (see http://www.bt.cdc.gov)

| Disease | Anthrax |

|---|---|

| Site(s) of infection; transmission mode | Cutaneous (contact with spores); RT (inhalation of spores); GIT (ingestion of spores [rare]) |

| Cutaneous and inhalation disease have occurred in past bioterrorist incidents | Comment: Spores can be inhaled into the lower respiratory tract. The infectious dose of Bacillus anthracis in humans by any route is not precisely known. In primates, the LD50 for an aerosol challenge with B anthracis is estimated to be 8,000 to 50,000 spores; the infectious dose may be as low as 1 to 3 spores. |

| Incubation period | Cutaneous: 1 to 12 days; RT: Usually 1 to 7 days, but up to 43 days reported; GIT: 15 to 72 hours |

| Clinical features | Cutaneous: Painless, reddish papule that develops a central vesicle or bulla in 1 to 2 days; over the next 3 to 7 days, the lesion becomes pustular and then necrotic, with black eschar and extensive surrounding edema |

| RT: Initial flu-like illness for 1 to 3 days with headache, fever, malaise, cough; by day 4, severe dyspnea and shock. Usually fatal (85% to 90%) if untreated; meningitis develops in 50% of RT cases. | |

| GIT: In intestinal form, necrotic, ulcerated edematous lesions develop in intestines with fever, nausea, and vomiting and progression to hematemesis and bloody diarrhea; 25% to 60% mortality | |

| Diagnosis | Cutaneous: Swabs of lesion (under eschar) for IHC, PCR, and culture; punch biopsy for IHC, PCR, and culture; vesicular fluid aspirate for Gram's stain and culture; blood culture if systemic symptoms present; acute and convalescent sera for ELISA serology |

| RT: CXR or CT demonstrating wide mediastinal widening and/or pleural effusion and hilar abnormalities; blood for culture and PCR; pleural effusion for culture, PCR, and IHC; CSF (if meningeal signs present) for IHC, PCR, and culture; acute and convalescent sera for ELISA serology; pleural and/or bronchial biopsy specimens for IHC | |

| GIT: Blood and ascites fluid, stool samples, rectal swabs, and swabs of oropharyngeal lesions, if present, for culture, PCR, and IHC | |

| Infectivity | Cutaneous: Person-to-person transmission from contact with lesion of untreated patient is possible but rare |

| RT and GIT: Person-to-person transmission does not occur | |

| Aerosolized powder, environmental exposures: Highly infectious if aerosolized | |

| Recommended precautions | Cutaneous: Standard Precautions; Contact Precautions if uncontained copious drainage present |

| RT and GIT: Standard Precautions. | |

| Aerosolized powder, environmental exposures: Respirator (N95 mask or powered air-purifying respirator), protective clothing; decontamination of persons with powder on them (see http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5135a3.htm) | |

| Hand hygiene: Handwashing for 30 to 60 seconds with soap and water or 2% chlorhexidene gluconate after spore contact; alcohol hand rubs are inactive against spores.981 | |

| Postexposure prophylaxis after environmental exposure: A 60-day course of antimicrobials (doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, or levofloxacin) and postexposure vaccine under IND. |

| Disease | Botulism |

|---|---|

| Site(s) of infection; transmission mode | GIT: Ingestion of toxin-containing food; RT: Inhalation of toxin containing aerosol. Comment: Toxin ingested or potentially delivered by aerosol in bioterrorist incidents. LD50 for type A is 0.001 μg/mL/kg. |

| Incubation period | 1 to 5 days. |

| Clinical features | Ptosis, generalized weakness, dizziness, dry mouth and throat, blurred vision, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphonia, and dysphagia, followed by symmetrical descending paralysis and respiratory failure. |

| Diagnosis | Clinical diagnosis: identification .of toxin in stool, serology, unless toxin-containing material available for toxin neutralization bioassays. |

| Infectivity | Not transmitted from person to person; exposure to toxin necessary for disease. |

| Recommended precautions | Standard Precautions. |

| Disease | Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever |

|---|---|

| Site(s) of infection; transmission mode | As a rule, infection develops after exposure of mucous membranes or RT, or through broken skin or percutaneous injury. |

| Incubation period | 2 to 19 days, usually 5 to 10 days |

| Clinical features | Febrile illnesses with malaise, myalgias, headache, vomiting, and diarrhea that are rapidly complicated by hypotension, shock, and hemorrhagic features. Massive hemorrhage in < 50% of patients. |

| Diagnosis | Etiologic diagnosis can be made using reverse-transcription-PCR, serologic detection of antibody and antigen, pathologic assessment with immunohistochemistry, and viral culture with electromicroscopic confirmation of morphology, |

| Infectivity | Person-to-person transmission occurs primarily through unprotected contact with blood and body fluids; percutaneous injuries (eg, needlestick) are associated with a high rate of transmission. Transmission in health care settings has been reported but can be prevented by use of Barrier Precautions. |

| Recommended precautions | Hemorrhagic fever–specific Barrier Precautions: If disease is believed to be related to intentional release of a bioweapon, then the epidemiology of transmission is unpredictable pending observation of disease transmission. Until the nature of the pathogen is understood and its transmission pattern confirmed, Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions should be used. Once the pathogen is characterized, if the epidemiology of transmission is consistent with natural disease, then Droplet Precautions can be substituted for Airborne Precautions. Emphasize the following: (1) use of sharps safety devices and safe work practices, (2) proper hand hygiene, (3) barrier protection against blood and body fluids on entry into room (single gloves and fluid-resistant or impermeable gown, face/eye protection with masks, goggles or face shields), and (4) appropriate waste handling. Use N95 or higher respirators when performing aerosol-generating procedures. In settings where AIIRs are unavailable or the large numbers of patients cannot be accommodated by existing AIIRs, observe Droplet Precautions (plus Standard and Contact Precautions) and segregate patients from those not suspected as having VHF infection. Limit blood draws to those essential to care. See the text for discussion and Appendix A for recommendations for naturally occurring VHFs. |

| Disease | Plague∗ |

|---|---|

| Site(s) of infection; transmission mode | RT: Inhalation of respiratory droplets. Comment: Pneumonic plague is most likely when used as a biological weapon, but some cases of bubonic and primary septicemia also may occur. Infective dose, 100 to 500 bacteria. |

| Incubation period | 1 to 6 days, usually 2 to 3 days. |

| Clinical features | Pneumonic: Fever, chills, headache, cough, dyspnea, rapid progression of weakness, and, in later stages, hemoptysis, circulatory collapse, and bleeding diathesis. |

| Diagnosis | Presumptive is diagnosis from Gram's stain or Wayson's stain of sputum, blood, or lymph node aspirate; definitive diagnosis is from cultures of same material or paired acute/convalescent serology. |

| Infectivity | Person-to-person transmission occurs through respiratory droplets. Risk of transmission is low during the first 20 to 24 hours of illness and requires close contact. Respiratory secretions probably are not infectious within a few hours after initiation of appropriate therapy. |

| Recommended precautions | Standard and Droplet Precautions until patients have received 48 hours of appropriate therapy. Chemoprophylaxis: Consider antibiotic prophylaxis for HCWs with close contact exposure. |

| Disease | Smallpox |

|---|---|

| Site(s) of infection; transmission mode | RT Inhalation of droplet or, rarely, aerosols; and skin lesions (contact with virus). |

| Comment: If used as a biological weapon, natural disease (which has not occurred since 1977) likely will result. | |

| Incubation period | 7 to 19 days (mean, 12 days). |

| Clinical features | Fever, malaise, backache, headache, and often vomiting for 2 to 3 days, followed by generalized papular or maculopapular rash (more on face and extremities), which becomes vesicular (on day 4 or 5) and then pustular; lesions all in same stage. |

| Diagnosis | Electron microscopy of vesicular fluid or culture of vesicular fluid by a World Health Organization–approved laboratory (CDC); detection by PCR available only at select LRN laboratories, the CDC, and US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. |

| Infectivity | Secondary attack rates up to 50% in unvaccinated persons. Infected persons may transmit disease from the time that rash appears until all lesions have crusted over (about 3 weeks). Infectivity is greatest during the first 10 days of rash. |

| Recommended precautions | Combined use of Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions should be maintained until all scabs have separated (3 to 4 weeks).† Only immune HCWs should care for patients. Postexposure vaccine should be provided within 4 days. |

| Vaccinia‡: HCWs to cover vaccination site with gauze and semipermeable dressing until scab separates (≥ 21 days). Hand hygiene should be observed. | |

| Adverse events with virus-containing lesions: Standard Precautions plus Contact Precautions until all lesions are crusted. |

| Disease | Tularemia |

|---|---|

| Site(s) of infection; transmission mode | RT: Inhalation of aerosolized bacteria; GIT: Ingestion of food or drink contaminated with aerosolized bacteria. |

| Comment: Pneumonic or typhoidal disease likely to occur after bioterrorist event using aerosol delivery. Infective dose, 10 to 50 bacteria. | |

| Incubation period | 2 to 10 days; usually 3 to 5 days. |

| Clinical features | Pneumonic: malaise, cough, sputum production, dyspnea. Typhoidal: fever, prostration, weight loss and frequently an associated pneumonia. |

| Diagnosis | Diagnosis usually made with serology on acute and convalescent serum specimens; bacterium can be detected by PCR (LRN) or isolated from blood and other body fluids on cysteine-enriched media or mouse inoculation. |

| Infectivity | Person-to-person spread is rare. Laboratory workers who encounter/handle cultures of this organism are at high risk for disease if exposed. |

| Recommended precautions | Standard Precautions |

AIIR, airborne infection isolation room; BSL, biosafety level; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; CXR, chest x-ray; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GIT, gastrointestinal tract; HCW, health care worker; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LD50, lethal dose for 50% of experimental animals; LRN, Laboratory Response Network; PAPR, powered air-purifying respirator; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RT, respiratory tract; VHF, viral hemorrhagic fever.

Pneumonic plague is not as contagious as is often thought. Historical accounts and contemporary evidence indicate that persons with plague usually transmit the infection only when the disease is in the end stage. These persons cough copious amounts of bloody sputum that contains many plague bacteria. Patients in the early stage of primary pneumonic plague (approximately the first 20 to 24 hours) apparently pose little risk (Wu L-T. A treatise on pneumonic plague. Geneva, Switzerland: League of Nations; 1926; Kool JL. Risk of person-to-person transmission of pneumonic plague. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1166-72). Antibiotic medication rapidly clears the sputum of plague bacilli, so that a patient generally is not infective within hours after initiation of effective antibiotic treatment (Butler TC. Plague and other Yersinia infections. In: Greenough WB, editor. Current topics in infectious disease. New York: Plenum; 1983). This means that in modern times, many patients will never reach a stage where they pose a significant risk to others. Even in the end stage of disease, transmission occurs only after close contact. Simple protective measures, such as wearing masks, maintaining good hygiene, and avoiding close contact, have been effective in interrupting transmission during many pneumonic plague outbreaks; in the United States, the last known case of person-to-person transmission of pneumonic plague occurred in 1925 (Kool JL. Risk of person-to-person transmission of pneumonic plague. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1166-72).

Transmission by the airborne route is a rare event. Airborne Precautions are recommended when possible, but in the event of mass exposures, Barrier Precautions and containment within a designated area are most important.204, 212

Vaccinia adverse events with lesions containing infectious virus include inadvertent autoinoculation, ocular lesions (blepharitis, conjunctivitis), generalized vaccinia, progressive vaccinia, and eczema vaccinatum. Bacterial superinfection also requires addition of Contact Precautions if exudates cannot be contained.216, 217

Table 4.

Recommendations for application of Standard Precautions for the care of all patients in all healthcare settings (see Sections II.D to II.J and III.A.1)

| Component | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Hand hygiene | After touching blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, contaminated items; immediately after removing gloves; between patient contacts |

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) | |

| Gloves | For touching blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, contaminated items, mucous membranes, and nonintact skin |

| Gown | During procedures and patient care activities when contact of clothing/exposed skin with blood/body fluids, secretions, and excretions is anticipated |

| Mask, eye protection (goggles), face shield∗ | During procedures and patient care activities likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood, body fluids, secretions, especially suctioning, endotracheal intubation |

| Soiled patient care equipment | Handle in a manner that prevents transfer of microorganisms to others and to the environment; wear gloves if visibly contaminated; perform hand hygiene |

| Environmental control | Develop procedures for routine care, cleaning, and disinfection of environmental surfaces, especially frequently touched surfaces in patient care areas |

| Textiles and laundry | Handle in a manner that prevents transfer of microorganisms to others and to the environment |

| Needles and other sharps | Do not recap, bend, break, or hand-manipulate used needles; if recapping is required, use a one-handed scoop technique only; use safety features when available; place used sharps in puncture-resistant container |

| Patient resuscitation | Use mouthpiece, resuscitation bag, other ventilation devices to prevent contact with mouth and oral secretions |

| Patient placement | Prioritize for single-patient room if patient is at increased risk of transmission, is likely to contaminate the environment, does not maintain appropriate hygiene, or is at increased risk of acquiring infection or developing adverse outcome after infection |

| Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette (source containment of infectious respiratory secretions in symptomatic patients, beginning at initial point of encounter, eg, triage and reception areas in emergency departments and physician offices) | Instruct symptomatic persons to cover mouth/nose when sneezing/coughing; use tissues and dispose in no-touch receptacle; observe hand hygiene after soiling of hands with respiratory secretions; wear surgical mask if tolerated or maintain spatial separation, >3 feet if possible. |

During aerosol-generating procedures on patients with suspected or proven infections transmitted by respiratory aerosols (eg, severe acute respiratory syndrome), wear a fit-tested N95 or higher respirator in addition to gloves, gown, and face/eye protection.

Table 5.

Components of a protective environment

| I. Patients: allogeneic hematopoeitic stem cell transplantation only |

| • Maintain in protective environment (PE) room except for required diagnostic or therapeutic procedures that cannot be performed in the room (eg, radiology, surgery) |

| • Respiratory protection (eg, N95 respirator) for the patient when leaving PE during periods of construction |

| II. Standard and Expanded Precautions |

| • Hand hygiene observed before and after patient contact |

| • Gown, gloves, mask not required for health care workers (HCWs) or visitors for routine entry into the room |

| • Use of gown, gloves, and mask by HCWs and visitors according to Standard Precautions and as indicated for suspected or proven infections for which transmission-based precautions are recommended |

| III. Engineering |

| • Central or point-of-use high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters (99.97% efficiency) filters capable of removing particles 0.3 μm in diameter in supply (incoming) air |

| • Well-sealed rooms: |

| - Proper construction of windows, doors, and intake and exhaust ports |

| - Ceilings: smooth, free of fissures, open joints, crevices |

| - Walls sealed above and below the ceiling |

| - If leakage detected, locate source and make necessary repairs |

| • Ventilation to maintain ≥12 air changes/hour |

| • Directed air flow; air supply and exhaust grills located so that clean, filtered air enters from one side of the room, flows across the patient's bed, and exits on opposite side of the room |

| • Positive room air pressure in relation to the corridor; pressure differential of >2.5 Pa (0.01-inch water gauge) |

| • Air flow patterns monitored and recorded daily using visual methods (eg, flutter strips, smoke tubes) or a hand-held pressure gauge |

| • Self-closing door on all room exits |

| • Back-up ventilation equipment (eg, portable units for fans or filters) maintained for emergency provision of ventilation requirements for PE areas, with immediate steps taken to restore the fixed ventilation system |

| • For patients who require both a PE and an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR), use an anteroom to ensure proper air balance relationships and provide independent exhaust of contaminated air to the outside, or place a HEPA filter in the exhaust duct. If an anteroom is not available, place patient in an AIIR and use portable ventilation units, industrial-grade HEPA filters to enhance filtration of spores. |

| IV. Surfaces |

| • Daily wet-dusting of horizontal surfaces using cloths moistened with EPA-registered hospital disinfectant/detergent |

| • Avoid dusting methods that disperse dust |

| • No carpeting in patient rooms or hallways |

| • No upholstered furniture and furnishings |

| V. Other |

| • No flowers (fresh or dried) or potted plants in PE rooms or areas |

| • Vacuum cleaner equipped with HEPA filters when vacuum cleaning is necessary |

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.11

A glossary of definitions used in this guideline also is provided. New to this edition of the guideline is a figure showing the recommended sequence for donning and removing PPE used for isolation precautions to optimize safety and prevent self-contamination during removal.

Appendix A: Type and Duration of Precautions Recommended for Selected Infections and Conditions

Appendix A provides an updated alphabetical list of most infectious agents and clinical conditions for which isolation precautions are recommended. A preamble to the appendix provides a rationale for recommending the use of 1 or more Transmission-Based Precautions in addition to Standard Precautions, based on a review of the literature and evidence demonstrating a real or potential risk for person-to-person transmission in health care settings. The type and duration of recommended precautions are presented, with additional comments concerning the use of adjunctive measures or other relevant considerations to prevent transmission of the specific agent. Relevant citations are included.

Prepublication of the Guideline on Preventing Transmission of MDROs

New to this guideline is a comprehensive review and detailed recommendations for prevention of transmission of MDROs. This portion of the guideline was published electronically in October 2006 and updated in November 2006 (Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L and HICPAC. Management of multidrug-resistant organisms in health care settings, 2006; available from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/ar/mdroGuideline2006.pdf), and is considered a part of the Guideline for Isolation Precautions. This section provides a detailed review of the complex topic of MDRO control in health care settings and is intended to provide a context for evaluation of MDRO at individual health care settings. A rationale and institutional requirements for developing an effective MDRO control program are summarized.

Although the focus of this guideline is on measures to prevent transmission of MDROs in health care settings, information concerning the judicious use of antimicrobial agents also is presented, because such practices are intricately related to the size of the reservoir of MDROs, which in turn influences transmission (eg, colonization pressure). Two tables summarize recommended prevention and control practices using 7 categories of interventions to control MDROs: administrative measures, education of HCWs, judicious antimicrobial use, surveillance, infection control precautions, environmental measures, and decolonization. Recommendations for each category apply to and are adapted for the various health care settings.

With the increasing incidence and prevalence of MDROs, all health care facilities must prioritize effective control of MDRO transmission. Facilities should identify prevalent MDROs at the facility, implement control measures, assess the effectiveness of control programs, and demonstrate decreasing MDRO rates. A set of intensified MDRO prevention interventions is to be added if the incidence of transmission of a target MDRO is not decreasing despite implementation of basic MDRO infection control measures, and when the first case of an epidemiologically important MDRO is identified within a health care facility.

Summary

This updated guideline responds to changes in health care delivery and addresses new concerns about transmission of infectious agents to patients and HCWs in the United States and infection control. The primary objective of the guideline is to improve the safety of the nation's health care delivery system by reducing the rates of HAIs.

Abbreviations Used in the Guideline

- AIA

American Institute of Architects

- AIIR

Airborne infection isolation room

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CF

Cystic fibrosis

- CJD

Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease

- ESBL

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- HAI

Health care–associated infection

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HEPA

High-efficiency particulate air

- HICPAC

Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HCW

Health care worker

- HFV

Hemorrhagic fever virus

- HSCT

Hematopoetic stem cell transplantation

- ICP

Infection prevention and control professional

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- LTCF

Long-term care facility

- MDR-GNB

Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli

- MDRO

Multidrug-resistant organism

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MSSA

Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- NIOSH

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- NNIS

National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance

- NSSP

Nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae

- OSHA

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PE

Protective environment

- PFGE

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

- PICU

Pediatric intensive care unit

- PPE

Personal protective equipment

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- vCJD

variant Creutzfeld-Jakob disease

- VISA

Vancomycin-intermediate/resistannt Staphylococcus aureus

- VRE

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci

- VRSA

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- WHO

World Health Organization

Part I: Review of Scientific Data Regarding Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings

I.A. Evolution of the 2007 Document

The Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health care Settings 2007 builds on a series of isolation and infection prevention documents promulgated since 1970. These previous documents are summarized and referenced in Table 1 and in Part I of the 1996 Guideline for Isolation Precautions in Hospitals.1

I.A.1. Objectives and Methods

The objectives of this guideline are to (1) provide infection control recommendations for all components of the health care delivery system, including hospitals, long-term care facilities, ambulatory care, home care, and hospice; (2) reaffirm Standard Precautions as the foundation for preventing transmission during patient care in all health care settings; (3) reaffirm the importance of implementing Transmission-Based Precautions based on the clinical presentation or syndrome and likely pathogens until the infectious etiology has been determined (Table 2); and (4) provide epidemiologically sound and, whenever possible, evidence-based recommendations.

This guideline is designed for use by individuals who are charged with administering infection control programs in hospitals and other health care settings. The information also will be useful for other HCWs, health care administrators, and anyone needing information about infection control measures to prevent transmission of infectious agents. Commonly used abbreviations are provided, and terms used in the guideline are defined in the Glossary.

Medline and PubMed were used to search for relevant studies published in English, focusing on those published since 1996. Much of the evidence cited for preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings is derived from studies that used “quasi-experimental designs,” also referred to as nonrandomized preintervention and postintervention study designs.2 Although these types of studies can provide valuable information regarding the effectiveness of various interventions, several factors decrease the certainty of attributing improved outcome to a specific intervention. These include: difficulties in controlling for important confounding variables, the use of multiple interventions during an outbreak, and results that are explained by the statistical principle of regression to the mean (eg, improvement over time without any intervention).3 Observational studies remain relevant and have been used to evaluate infection control interventions.4, 5 The quality of studies, consistency of results, and correlation with results from randomized controlled trials, when available, were considered during the literature review and assignment of evidence-based categories (see Part IV: Recommendations) to the recommendations in this guideline. Several authors have summarized properties to consider when evaluating studies for the purpose of determining whether the results should change practice or in designing new studies.2, 6, 7

I.A.2. Changes or Clarifications in Terminology

This guideline contains 4 changes in terminology from the 1996 guideline:

-

1.

The term “nosocomial infection” is retained to refer only to infections acquired in hospitals. The term “health care–associated infection” (HAI) is used to refer to infections associated with health care delivery in any setting (eg, hospitals, long-term care facilities, ambulatory settings, home care). This term reflects the inability to determine with certainty where the pathogen was acquired, because patients may be colonized with or exposed to potential pathogens outside of the health care setting before receiving health care, or may develop infections caused by those pathogens when exposed to the conditions associated with delivery of health care. In addition, patients frequently move among the various settings within the health care system.8

-

2.

A new addition to the practice recommendations for Standard Precautions is respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette. Whereas Standard Precautions generally apply to the recommended practices of HCWs during patient care, respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette applies broadly to all persons who enter a health care setting, including HCWs, patients, and visitors. These recommendations evolved from observations during the SARS epidemic that failure to implement basic source control measures with patients, visitors, and HCWs with signs and symptoms of respiratory tract infection may have contributed to SARS-CoV transmission. This concept has been incorporated into CDC planning documents for SARS and pandemic influenza.9, 10

-

3.

The term “Airborne Precautions” has been supplemented by the term “Airborne Infection Isolation Room” (AIIR), to achieve consistency with the Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health Care Facilities,11 the Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Health Care Settings 2005,12 and the American Institute of Architects (AIA) 2006 guidelines for design and construction of hospitals.13

-

4.

A set of prevention measures known as the protective environment (PE) has been added to the precautions for preventing HAIs. These measures, which have been defined in previous guidelines, consist of engineering and design interventions aimed at decreasing the risk of exposure to environmental fungi for severely immunocompromised patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT during the times of highest risk, usually the first 100 days posttransplantation or longer in the presence of graft-versus-host disease.11, 13, 14, 15 Recommendations for a PE apply only to acute care hospitals that provide care to patients undergoing HSCT.

I.A.3. Scope

This guideline, like its predecessors, focuses primarily on interactions between patients and health care providers. The Guidelines for the Prevention of MDRO Infection were published separately in November 2006 and are available online at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/index.html. Several other HICPAC guidelines to prevent transmission of infectious agents associated with health care delivery are cited, including Guideline for Hand Hygiene, Guideline for Environmental Infection Control, Guideline for Prevention of Health Care–Associated Pneumonia, and Guideline for Infection Control in Health Care Personnel.11, 14, 16, 17 In combination, these provide comprehensive guidance on the primary infection control measures for ensuring a safe environment for patients and HCWs.

This guideline does not discuss in detail specialized infection control issues in defined populations that are addressed elsewhere (eg, Recommendations for Preventing Transmission of Infections Among Chronic Hemodialysis Patients, Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Health Care Facilities 2005, Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health Care Settings, and Infection Control Recommendations for Patients With Cystic Fibrosis.12, 18, 19, 20 An exception has been made by including abbreviated guidance for a PE used for allogeneic HSCT recipients, because components of the PE have been defined more completely since publication of the Guidelines for Preventing Opportunistic Infections Among HSCT Recipients in 2000 and the Guideline for Environmental Infection Control in Health Care Facilities.11, 15

I.B. Rationale for Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions in Health Care Settings

Transmission of infectious agents within a health care setting requires 3 elements: a source (or reservoir) of infectious agents, a susceptible host with a portal of entry receptive to the agent, and a mode of transmission for the agent. This section describes the interrelationship of these elements in the epidemiology of HAIs.

I.B.1. Sources of Infectious Agents

Infectious agents transmitted during health care derive primarily from human sources but inanimate environmental sources also are implicated in transmission. Human reservoirs include patients,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 HCWs,17, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 and household members and other visitors.40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Such source individuals may have active infections, may be in the asymptomatic and/or incubation period of an infectious disease, or may be transiently or chronically colonized with pathogenic microorganisms, particularly in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Other sources of HAIs are the endogenous flora of patients (eg, bacteria residing in the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract).46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54

I.B.2. Susceptible Hosts

Infection is the result of a complex interrelationship between a potential host and an infectious agent. Most of the factors that influence infection and the occurrence and severity of disease are related to the host. However, characteristics of the host–agent interaction as it relates to pathogenicity, virulence, and antigenicity also are important, as are the infectious dose, mechanisms of disease production, and route of exposure.55 There is a spectrum of possible outcomes after exposure to an infectious agent. Some persons exposed to pathogenic microorganisms never develop symptomatic disease, whereas others become severely ill and even die. Some individuals are prone to becoming transiently or permanently colonized but remain asymptomatic. Still others progress from colonization to symptomatic disease either immediately after exposure or after a period of asymptomatic colonization. The immune state at the time of exposure to an infectious agent, interaction between pathogens, and virulence factors intrinsic to the agent are important predictors of an individual's outcome. Host factors such as extremes of age and underlying disease (eg, diabetes56, 57, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome [HIV/AIDS],58, 59 malignancy, and transplantation18, 60, 61) can increase susceptibility to infection, as can various medications that alter the normal flora (eg, antimicrobial agents, gastric acid suppressors, corticosteroids, antirejection drugs, antineoplastic agents, immunosuppressive drugs). Surgical procedures and radiation therapy impair defenses of the skin and other involved organ systems. Indwelling devices, such as urinary catheters, endotracheal tubes, central venous and arterial catheters,62, 63, 64 and synthetic implants, facilitate development of HAIs by allowing potential pathogens to bypass local defenses that ordinarily would impede their invasion and by providing surfaces for development of biofilms that may facilitate adherence of microorganisms and protect from antimicrobial activity.65 Some infections associated with invasive procedures result from transmission within the health care facility; others arise from the patient's endogenous flora.46, 47, 48, 49, 50 High-risk patient populations with noteworthy risk factors for infection are discussed further in Sections I.D, I.E, and I.F.

I.B.3. Modes of Transmission

Several classes of pathogens can cause infection, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, and prions. The modes of transmission vary by type of organism, and some infectious agents may be transmitted by more than 1 route. Some are transmitted primarily by direct or indirect contact, (eg, herpes simplex virus [HSV], respiratory syncytial virus, S aureus), others by the droplet, (eg, influenza virus, Bordetella pertussis) or airborne routes (eg, Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Other infectious agents, such as bloodborne viruses (eg, hepatitis B virus [HBV], hepatitis C virus [HCV], HIV), are rarely transmitted in health care settings through percutaneous or mucous membrane exposure. Importantly, not all infectious agents are transmitted from person to person; these are listed in Appendix A. The 3 principal routes of transmission—contact, droplet, and airborne—are summarized below.

I.B.3.a. Contact Transmission

The most common mode of transmission, contact transmission is divided into 2 subgroups: direct contact and indirect contact.

I.B.3.a.i. Direct Contact Transmission

Direct transmission occurs when microorganisms are transferred from an infected person to another person without a contaminated intermediate object or person. Opportunities for direct contact transmission between patients and HCWs have been summarized in HICPAC's Guideline for Infection Control in Health Care Personnel, 1998 17 and include the following:

-

•

Blood or other blood-containing body fluids from a patient directly enters a HCW's body through contact with a mucous membrane66 or breaks (ie, cuts, abrasions) in the skin.67

-

•

Mites from a scabies-infested patient are transferred to a HCW's skin while he or she is in direct ungloved contact with the patient's skin.68, 69

-

•

A HCW develops herpetic whitlow on a finger after contact with HSV when providing oral care to a patient without using gloves, or HSV is transmitted to a patient from a herpetic whitlow on an ungloved hand of a HCW.70, 71

I.B.3.a.ii. Indirect Contact Transmission

Indirect transmission involves the transfer of an infectious agent through a contaminated intermediate object or person. In the absence of a point-source outbreak, it is difficult to determine how indirect transmission occurs. However, extensive evidence cited in the Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health Care Settings suggests that the contaminated hands of HCWs are important contributors to indirect contact transmission.16 Examples of opportunities for indirect contact transmission include the following:

-

•

A HCWs' hands may transmit pathogens after touching an infected or colonized body site on 1 patient or a contaminated inanimate object, if hand hygiene is not performed before touching another patient.72, 73

-

•

Patient-care devices (eg, electronic thermometers, glucose monitoring devices) may transmit pathogens if devices contaminated with blood or body fluids are shared between patients without cleaning and disinfecting between patients.74, 75, 76, 77

-

•

Shared toys may become a vehicle for transmitting respiratory viruses (eg, respiratory syncytial virus [RSV]24, 78, 79 or pathogenic bacteria (eg, Pseudomonas aeruginosa 80) among pediatric patients.

-

•

Instruments that are inadequately cleaned between patients before disinfection or sterilization (eg, endoscopes or surgical instruments)81, 82, 83, 84, 85 or that have manufacturing defects that interfere with the effectiveness of reprocessing86, 87 may transmit bacterial and viral pathogens.

Clothing, uniforms, laboratory coats, or isolation gowns used as PPE may become contaminated with potential pathogens after care of a patient colonized or infected with an infectious agent, (eg, MRSA,88 vancomycin-resistant enterococci [VRE],89 and C difficile 90). Although contaminated clothing has not been implicated directly in transmission, the potential exists for soiled garments to transfer infectious agents to successive patients.

I.B.3.b. Droplet Transmission

Droplet transmission is technically a form of contact transmission; some infectious agents transmitted by the droplet route also may be transmitted by direct and indirect contact routes. However, in contrast to contact transmission, respiratory droplets carrying infectious pathogens transmit infection when they travel directly from the respiratory tract of the infectious individual to susceptible mucosal surfaces of the recipient, generally over short distances, necessitating facial protection. Respiratory droplets are generated when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks91, 92 or during such procedures as suctioning, endotracheal intubation,93, 94, 95, 96 cough induction by chest physiotherapy,97 and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.98, 99 Evidence for droplet transmission comes from epidemiologic studies of disease outbreaks,100, 101, 102, 103 from experimental studies,104 and from information on aerosol dynamics.91, 105 Studies have shown that the nasal mucosa, conjunctivae, and, less frequently, the mouth are susceptible portals of entry for respiratory viruses.106 The maximum distance for droplet transmission is currently unresolved; pathogens transmitted by the droplet route have not been transmitted through the air over long distances, in contrast to the airborne pathogens discussed below. Historically, the area of defined risk has been a distance of < 3 feet around the patient, based on epidemiologic and simulated studies of selected infections.103, 104 Using this distance for donning masks has been effective in preventing transmission of infectious agents through the droplet route. However, experimental studies with smallpox107, 108 and investigations during the global SARS outbreaks of 2003101 suggest that droplets from patients with these 2 infections could reach persons located 6 feet or more from their source. It is likely that the distance that droplets travel depends on the velocity and mechanism by which respiratory droplets are propelled from the source, the density of respiratory secretions, environmental factors (eg, temperature, humidity), and the pathogen's ability to maintain infectivity over that distance.105 Thus, a distance of < 3 feet around the patient is best considered an example of what is meant by “a short distance from a patient” and should not be used as the sole criterion for determining when a mask should be donned to protect from droplet exposure. Based on these considerations, it may be prudent to don a mask when within 6 to 10 feet of the patient or on entry into the patient's room, especially when exposure to emerging or highly virulent pathogens is likely. More studies are needed to gain more insight into droplet transmission under various circumstances.

Droplet size is another variable under investigation. Droplets traditionally have been defined as being > 5 μm in size. Droplet nuclei (ie, particles arising from desiccation of suspended droplets) have been associated with airborne transmission and defined as < 5 μm in size,105 a reflection of the pathogenesis of pulmonary tuberculosis that is not generalizeable to other organisms. Observations of particle dynamics have demonstrated that a range of droplet sizes, including those of diameter ≥ 30 μm, can remain suspended in the air.109 The behavior of droplets and droplet nuclei affect recommendations for preventing transmission. Whereas fine airborne particles containing pathogens that are able to remain infective may transmit infections over long distances, requiring AIIR to prevent its dissemination within a facility; organisms transmitted by the droplet route do not remain infective over long distances and thus do not require special air handling and ventilation. Examples of infectious agents transmitted through the droplet route include B pertussis,110 influenza virus,23 adenovirus,111 rhinovirus,104 Mycoplasma pneumoniae,112 SARS-CoV,21, 96, 113 group A streptococcus,114 and Neisseria meningitides.95, 103, 115 Although RSV may be transmitted by the droplet route, direct contact with infected respiratory secretions is the most important determinant of transmission and consistent adherence to Standard Precautions plus Contact Precautions prevents transmission in health care settings.24, 116, 117

Rarely, pathogens that are not transmitted routinely by the droplet route are dispersed into the air over short distances. For example, although S aureus is transmitted most frequently by the contact route, viral upper respiratory tract infection has been associated with increased dispersal of S aureus from the nose into the air for a distance of 4 feet under both outbreak and experimental conditions; this is known as the “cloud baby” and “cloud adult” phenomenon.118, 119, 120

I.B.3.c. Airborne Transmission

Airborne transmission occurs by dissemination of either airborne droplet nuclei or small particles in the respirable size range containing infectious agents that remain infective over time and distance (eg, spores of Aspergillus spp and M tuberculosis). Microorganisms carried in this manner may be dispersed over long distances by air currents and may be inhaled by susceptible individuals who have not had face-to-face contact with (or even been in the same room with) the infectious individual.121, 122, 123, 124 Preventing the spread of pathogens that are transmitted by the airborne route requires the use of special air handling and ventilation systems (eg, AIIRs) to contain and then safely remove the infectious agent.11, 12 Infectious agents to which this applies include M tuberculosis,124, 125, 126, 127 rubeola virus (measles),122 and varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox).123 In addition, published data suggest the possibility that variola virus (smallpox) may be transmitted over long distances through the air under unusual circumstances, and AIIRs are recommended for this agent as well; however, droplet and contact routes are the more frequent routes of transmission for smallpox.108, 128, 129 In addition to AIIRs, respiratory protection with a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)-certified N95 or higher-level respirator is recommended for HCWs entering the AIIR, to prevent acquisition of airborne infectious agents such as M tuberculosis.12

For certain other respiratory infectious agents, such as influenza130, 131 and rhinovirus,104 and even some gastrointestinal viruses (eg, norovirus132 and rotavirus133), there is some evidence that the pathogen may be transmitted through small-particle aerosols under natural and experimental conditions. Such transmission has occurred over distances > 3 feet but within a defined air space (eg, patient room), suggesting that it is unlikely that these agents remain viable on air currents that travel long distances. AIIRs are not routinely required to prevent transmission of these agents. Additional issues concerning small-particle aerosol transmission of agents that are most frequently transmitted by the droplet route are discussed below.

I.B.3.d. Emerging Issues Concerning Airborne Transmission of Infectious Agents

I.B.3.d.i. Transmission From Patients

The emergence of SARS in 2002, the importation of monkeypox into the United States in 2003, and the emergence of avian influenza present challenges to the assignment of isolation categories due to conflicting information and uncertainty about possible routes of transmission. Although SARS-CoV is transmitted primarily by contact and/or droplet routes, airborne transmission over a limited distance (eg, within a room) has been suggested, although not proven.134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141 This is true of other infectious agents as well, such as influenza virus130 and noroviruses.132, 142, 143 Influenza viruses are transmitted primarily by close contact with respiratory droplets,23, 102 and acquisition by HCWs has been prevented by Droplet Precautions, even when positive-pressure rooms were used in one center.144 However, inhalational transmission could not be excluded in an outbreak of influenza in the passengers and crew of an aircraft.130 Observations of a protective effect of ultraviolet light in preventing influenza among patients with tuberculosis during the influenza pandemic of 1957–1958 have been used to suggest airborne transmission.145, 146

In contrast to the strict interpretation of an airborne route for transmission (ie, long distances beyond the patient room environment), short-distance transmission by small-particle aerosols generated under specific circumstances (eg, during endotracheal intubation) to persons in the immediate area near the patient also has been demonstrated. Aerosolized particles < 100 μm in diameter can remain suspended in air when room air current velocities exceed the terminal settling velocities of the particles.109 SARS-CoV transmission has been associated with endotracheal intubation, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.93, 94, 96, 98, 141 Although the most frequent routes of transmission of noroviruses are contact and foodborne and waterborne routes, several reports suggest that noroviruses also may be transmitted through aerosolization of infectious particles from vomitus or fecal material.142, 143, 147, 148 It is hypothesized that the aerosolized particles are inhaled and subsequently swallowed.

Roy and Milton have proposed a new classification for aerosol transmission when evaluating routes of SARS transmission:

-

•

Obligate. Under natural conditions, disease occurs after transmission of the agent only through inhalation of small-particle aerosols (eg, tuberculosis).

-

•

Preferential. Natural infection results from transmission through multiple routes, but small-particle aerosols are the predominant route (eg, measles, varicella).

-

•

Opportunistic. Under special circumstances, agents that naturally cause disease through other routes may be transmitted through small-particle aerosols.149

This conceptual framework can explain rare occurrences of airborne transmission of agents that are transmitted most frequently by other routes (eg, smallpox, SARS, influenza, noroviruses). Concerns about unknown or possible routes of transmission of agents associated with severe disease and no known treatment often result in the adoption of overextreme prevention strategies, and recommended precautions may change as the epidemiology of an emerging infection becomes more well defined and controversial issues are resolved.

I.B.3.d.ii. Transmission From the Environment