Abstract

The genetic diversity of 16 canine coronavirus (CCoV) samples is described. Samples were obtained from pups infected naturally living in different areas. Sequence data were obtained from the M gene and pol1a and pol1b regions. The phylogenetic relationships among these sequences and sequences published previously were determined. The canine samples segregated in two separate clusters. Samples of the first cluster were intermingled with reference strains of CCoV genotype and therefore could be assigned to this genotype. The second cluster segregated separately from CCoV and feline coronavirus genotypes and therefore these samples may represent genetic outliers. The reliability of the classification results was confirmed by repeating the phylogenetic analysis with nucleotide and amino acid sequences from multiple genomic regions.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Dog, Genotype

1. Introduction

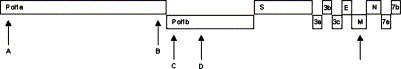

Coronaviruses, a family of viruses belonging to the newly established order of the Nidovirales (Siddell, 1995, de Vries et al., 1997, Enjuanes et al., 2000b), are pathogens of mammals and birds; based on genetic comparison, three distinct clusters can be distinguished. One of these clusters also shows antigenic cross-reactivity and contains the canine coronavirus (CCoV), the swine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), the porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus, the feline coronaviruses (FCoVs) and the human coronavirus 229E (HCoV 229E). Virus particles are enveloped and contain a non-segmented, positive stranded RNA genome 27–32 kb in size (Siddell, 1995, Lai and Cavanagh, 1997). The genome contains two large open reading frames (ORFs), 1a and 1b, encoding two polyproteins leading to the viral replicase formation. Downstream to the ORF1b, there are 8–10 small ORFs, expressed through subgenomic mRNAs and coding for the structural proteins S, E, M, the nucleocapsid (N) protein, and a number of presumptive non-structural proteins (Luytjes, 1995, Enjuanes et al., 2000a) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of CCoV genome. Arrows indicate the position of the genome fragments analysed.

The trimeric spike (S) protein, the major inducer of virus-neutralizing antibodies (Gebauer et al., 1991), forms characteristic viral peplomers which are involved in virus attachment on the cell receptors and in virus-cell fusion (de Haan et al., 2000). The small membrane protein (E), recognized recently as a structural component of the coronavirions, has been found to be important for viral envelope assembling (Raamsman et al., 2000). The M protein, the most abundant structural component, is a type III glycoprotein consisting of a short amino-terminal ectodomain, a triple-spanning transmembrane domain, and a long carboxyl-terminal inner domain (Rottier, 1995). The M protein induces antibody-dependent complement-mediated virus neutralization although its function has not yet been fully clarified (Woods et al., 1987).

One of the most interesting aspects of coronavirus replication is the occurrence of high-frequency homologous RNA recombination (Lai et al., 1985, Makino et al., 1986). This process is thought to be mediated by a ‘copy-choice’ mechanism (Cooper et al., 1974, Kirkegaard and Baltimore, 1986, Makino et al., 1986). Recombination of coronavirus genomes has been observed in tissue culture (Lai et al., 1985, Makino et al., 1986, Sanchez et al., 1999, Kuo et al., 2000), in animals infected experimentally (Keck et al., 1988), and in embryonated eggs (Kottier et al., 1995). There is also evidence for homologous recombination occurring in mouse hepatitis virus in the field (Kusters et al., 1990, Wang et al., 1993, Jia et al., 1995) and recent findings suggest that it may also be an important factor in the evolution of FCoVs (Herrewegh et al., 1995, Herrewegh et al., 1998, Vennema et al., 1995, Motokawa et al., 1996). Two FCoV serotypes (I and II) have been demonstrated that are distinguishable readily in vitro by virus neutralization assay (Hohdatsu et al., 1991, Hohdatsu et al., 1992). The FCoV type II strains have a CCoV-like S gene which is thought to provide a growth advantage or a mechanism for escaping from the immune response (de Groot et al., 1987). Comparative sequence analysis of type I and type II FCoV and CCoV genomes suggests that the FCoV type II strains arose from a homologous RNA recombination between CCoV and a type I FCoV (Herrewegh et al., 1995, Vennema et al., 1995, Motokawa et al., 1996).

Accumulation of point mutations (as well as small insertions and deletions) in coding and non-coding sequences is the dominant force in the microevolution of (+) RNA viruses, resulting in proliferation of virus strains, serotypes and subtypes (Dolja and Carrington, 1992). Extremely large (+) RNA virus genomes, such as those of coronaviruses, are predicted to accumulate several base substitutions per round of replication because of the high error frequencies of RNA polymerase (Jarvis and Kirkegaard, 1991).

Comparative studies of CCoV strains have been hampered because only few strains proved to be suitable for growth in vitro. The development of PCR assays for CCoV (Bandai et al., 1999, Pratelli et al., 1999b, Naylor et al., 2001) has provided important information on the epidemiology of CCoV, which has been detected in as much as one-third of the pups affected with diarrhoea (Pratelli et al., 2000), often as co-infections with other canine pathogens such as parvovirus, rotavirus and adenovirus (Appel et al., 1979, Yasoshima et al., 1983, Martin and Zeidner, 1992, Pratelli et al., 1999a, Pratelli et al., 2001a).

This paper describes a comparative analysis of the genes encoding for both the M protein and polymerase performed on CCoV isolates and faecal samples of pups that were positive for CCoV by PCR.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Virus strains and clinical samples

The reference CCoV strain S378 (supplied by L.E. Carmichael, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY), and the cell culture-adapted CCoV strains, 45/93 (Buonavoglia et al., 1994), A-2/99, 144/01, 257/98 and 65/00-30, were tested. Virus isolates were grown on the A-72 canine cell line. Eleven faecal samples (107/99, A-32/99, 79/99, 74/99B, 74/99C, 103/99A, 83/99, 103/99E, C-27/3, 93/00, 259/01) from 2 to 6 month-old pups affected with diarrhoea and negative to virus isolation but PCR positive to CCoV, were also tested. All the pups came from urban areas of different regions of southern Italy and they were either free-roaming dogs or family pets. Faecal samples were collected into sterile tubes, transported to our laboratories and processed within 48 h.

2.2. In vitro amplification by PCR

Viral RNA was extracted from faecal samples and from infected A-72 cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen GmbH, Germany). Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR was carried out using the primer pair M5/M6 that amplified the M gene of CCoV. Briefly, reverse transcription was performed in a total reaction volume of 20 μl containing PCR buffer 1× (KCl 50 mM, Tris–HCl 10 mM, pH 8.3), MgCl2 5 mM, 1 mM of each deoxynucleotide (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP), RNase 1 U, MuLV RT 2.5 U, random hexamers 2.5 U. Synthesis of cDNA was carried out at 42 °C for 30 min, followed by a denaturation step at 99 °C for 5 min. The mixture was made up to a total volume of 100 μl, containing PCR buffer 1×, MgCl2 2 mM, Amplitaq Gold DNA polymerase 2.5 U and 50 pmol of each primers M5 and M6. The PCR mixture was subjected to 35 cycles (94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min) in a DNA Thermal Cycler.

In addition, RT-PCR assays were carried out on four fragments of the polymerase gene located in the ORF1a region, fragments A (p493/p247) and B (p685/p670), and ORF1b region, fragments C (p650/p652) and D (p686/p687), as reported by Herrewegh et al. (1998). C-DNA syntheses were undertaken at 42 °C for 30 min, followed by 5 min at 99 °C for all the fragments. The PCR reaction was carried out for 40 cycles (94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min). The sequence and position of all the primers are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR amplification and sequence analysis

| Primer | Sequence 5′–3′ | Sense | Position | Amplificon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M5 | CCTTGTTTGAACTAAACAAAATGAAG | + | 6382–6407a | 835 |

| M6 | TCCCTGAGAGGCCATTTAGA | − | 7197–7217a | |

| p493b | GTAGTAGCATCACTCTGCACTTC | + | 1575–1597c | 320 |

| p247b | CCGTTGTGGTGTCACATTAAC | − | 1895–1875c | |

| p685b | GCCCTTGAGTATAACTTGTGAG | + | 11 531–11 552c | 389 |

| p670b | TCAGTGGTTTACCAGCTTGCA | − | 11 920–11 899c | |

| p650b | TGGTGCTGTTGCTGAGCATGA | + | 12 574–12 594c | 749 |

| p652b | ACAACTACTGGTACACCATCAA | − | 13 323–13 302c | |

| p686b | GAAACTGTGAAAGCTAAGGAGG | + | 15 500–15 521c | 472 |

| p687b | ACACAATGAGATTTACCGCTACC | − | 15 972–15 950c |

Primers position is referred to the sequence of stain Insavc (accession: D13096).

Primers locations are indicated as originally reported in the corresponding papers.

2.3. Sequencing and phylogeny

The PCR products were purified through Ultrafree-DA columns (Amicon, Millipore, Bedford, USA) and subjected to sequence analysis with the dideoxynucleotide chain-termination method, using ABI-PRISM 377 (Perkin Elmer, Applied Biosystem Instruments). For each region, the nucleotide sequence of each sample was determined in both directions on at least two separate amplicons. Sequence data were aligned to reference strains by using with CLUSTALW program (version 1.8) with the following settings: gap opening penalty of 10.0 and gap extension penalty of 10.0 with transition weighted, and manually refined with GENEDOC (version 2.6.002; http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc). The phylogenetic methods used were from phylip software package developed by J. Felsestein (version 3.5c; http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html). Nucleotide and amino acid distances were calculated by Kimura's two-parameter and p-distance methods, respectively. Phylogenetic trees were produced by using the NEIGHBOR-JOINING method on 1000 bootstrap replicates, followed by FITCH-MARGOLIASH to obtain proportional branch lengths (nucleotide and amino acid sequences), and by DNAML with a transition/transversion ratio of 2.000 and randomizing the data input (nucleotide sequences), and PROTPARS on 500 bootstrap replicates (amino acid sequences). Trees were drawn with treeview (version 1.6.6; http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/rod.html).

2.4. Nucleotide sequence accession number

The nucleotide sequence of the sample 259/01 will appear in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession no. AF502583. The references for and the nucleotide sequence accession numbers of the M and polymerase genes of the coronavirus strains mentioned in this study are reported in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Accession numbers of the M and pol genes of the strains mentioned in this study

| Strain | Accession | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Insavc | D13096 | Horsburgh et al. (1992) |

| FCoV 79-1146 | AF326575 | de Groot et al. (1987) |

| FCoV 79-1683 | Y13921 | Herrewegh et al. (1998) |

| FCoV TN406 | X90570 | Herrewegh et al. (1998) |

| FCoV UCD-1 | X90575 | Herrewegh et al. (1998) |

| TGEV-Purdue | NC_002306 | Almazan et al. (2000) |

3. Results

A total 17 samples were analyzed: the reference CCoV strain S378, five cell culture-adapted CCoV strains and eleven faecal samples of pups. PCR amplicons of the expected size were obtained with the primer pairs M5/M6, p493-p247, p685/p670, p650/p652, p686/p687. Some pol regions of several faecal samples were not amplified, probably due to viral loads close to the sensitivity threshold of the RT-PCR assays. The observation that in vitro-grown isolates were amplifiable with all primer sets used (excepted 65/00-30 isolate that scored negative with pol1a B primers) strengthened this hypothesis (Table 3 for the details).

Table 3.

List of the viruses analysed in this study: the genome fragments successfully amplified and sequenced are indicated

| Samples | M | pol1a (A) | pol1a (B) | pol1b (C) | pol1b (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/378 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 257/98 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 45/93 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 83/99 | + | − | − | − | − |

| 93/00 | + | + | + | + | + |

| A-2/99 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 144/01 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 65/00-30 | + | + | − | + | + |

| 103/99A | + | + | + | + | + |

| 103/99E | + | + | + | + | + |

| C-27/3* | + | + | − | + | + |

| 107/99* | + | + | − | + | − |

| 74/99C* | + | + | − | + | + |

| 74/99B* | + | + | − | − | + |

| 79/99* | + | − | − | − | + |

| A-32/99* | + | + | + | − | + |

| 259/01* | + | + | + | + | + |

+, amplified; −, not amplified.

FCoV-like CCoVs.

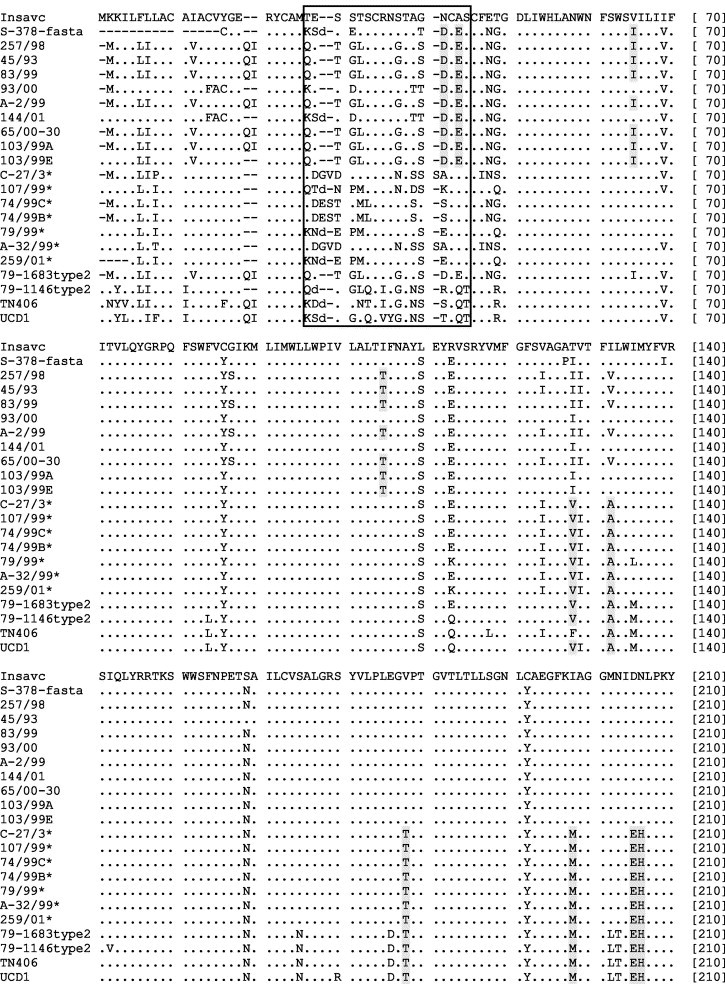

Multiple alignments showed that the studied sequences differed from each other, thus ruling out possible contaminations. Multiple nucleotide alignments deduced from pol1a and pol1b regions were straightforward, whereas those obtained from the M gene exhibited numerous insertions and deletions and needed to be refined by manual editing. Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences showed that the great majority of nonsynonymous substitutions were localized within the NH2-end ectodomain of the M protein. Although no consistent pattern was observed, all the insertions and deletions were in-frame and located in four defined positions. Moreover, initial direct inspection revealed that seven Italian samples analysed contained amino acid residues which were typical of FCoV isolates: Ile→Val-128, Ile/Val→Ala-132, Val→Thr-178, Ile→Met-197, Asp→Glu-205, Asn→His-206, Lys→Gln-228, Asp→Glu-251 and Gln→His-260; thus highlighting the fact that these specimens contained coronavirus RNA with more deduced amino acid similarity to FCoV than to CCoV in this region (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Amino acid sequence of the M gene of coronaviruses from dog and cat. Asterisks indicate FCoV-like CCoVs. The NH3-terminus ectodomain is boxed.

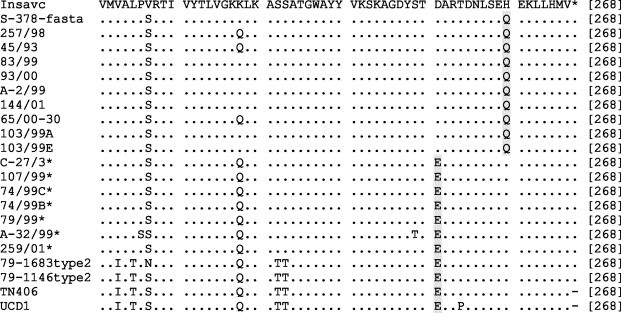

Phylogenetic relationships were inferred from the genetic distances by constructing phylogenetic trees using the distance-based methods NEIGHBOR-JOINING and FITCH-MARGOLIASH, and the character-state method DNAML. For this analysis, distance values for the M gene were recalculated by trimming the ectodomain region (i.e. by reducing the sequence stretch analyzed from 835 to 681 bp) which did not allow precise phylogenetic inference because of its high heterogeneity (homoplasy). Trees were rooted by using the porcine TGEV isolate Purdue as an outgroup. To appraise the sensitivity of NEIGHBOR-JOINING to the input order of species, the program was run, in a pilot study, by using either fixed or multiple randomized orders of M sequences and by repeating the process ten times. The resulting trees differed slightly but phylogroups and outliers were identical (trees not shown). Since the randomizing option was time-consuming and did not influence segregation, NEIGHBOR-JOINING trees were produced from a fixed order of bootstrapped sequences only and by using the multiple data set option (100 reiterations). Branch lengths were then calculated from the consensus trees using FITCH-MARGOLIASH. Topologies of trees from all of the genomic regions analyzed were very similar, the major phylogenetic lineages defining the FCoV and CCoV genotypes were delineated clearly and generally supported by high bootstrap values. Irrespective of the genome portion analyzed, the CCoV strains Insavc, S378, 45/93, 257/98, A-2/99, 144/01 and 65/00-30, and FCoV TN406 and UCD1, clustered into different phylogroups. Both the FCoV type II isolates segregated together with the CCoV isolates when analyzed for pol1b (region D); when analyzed for pol1b (region C) only the FCoV 79-1683 strain segregated with CCoV.

The Italian samples analyzed segregated in two different clusters, indicating a distinct genetic relatedness. This result was clearly evident in the trees obtained from the M gene where samples 83/99, 93/00 103/99A and 103/99E clustered with prototype canine isolates thus behaving as typical CCoV strains, whereas samples A32/99, C27/3, 74/99B, 74/99C, 79/99, 107/99 and 259/01 segregated together giving rise to an outlier cluster localized between the feline and canine genotypes. Segregations were supported by high bootstrap values and statistical significance thus emphasizing the robustness of tree topology (Fig. 3 a). Although the number of samples analyzed was smaller and the bootstrap values were lower than for the M gene, the segregation pattern of Italian samples was observed consistently also when analyzed in pol1b-region D (Fig. 3e). The topology of the trees built with the other genome stretches shown confirmed the presence of typical CCoV strains and CCoVs that could not be assigned to either CCoV or FCoV genotypes, although these samples did not fall within a single branch but were dispersed into smaller clusters and located between the outgroup strain and samples belonging to FCoV genotype (Fig. 3b–d). Similar findings were also observed by analyzing the amino acid sequences (data not shown). Altogether, these results suggested that outlier samples may have undergone partly separate evolutions from typical CCoV strains.

Fig. 3.

Evolutionary relationships among coronavirus strains based on nucleotide sequences of M gene (a), pol1a-region A (b), pol1a-region B (c), pol1b-region C (d) and pol1b-region D (e). Branching pattern of the trees was obtained by NEIGHBOR-JOINING. Bootstrap values above 60 out of 100 are shown at the branch points. Double asterisks indicate branches at P<0.01 as calculated by DNAML. Bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions/site, calculated by the Kimura's two-parameter model with a transition/transversion of 2.00. Numbers indicate samples amplified and sequenced from faecal samples. Empty and solid circles indicate, respectively, FCoV isolates listed in Table 2 and CCoV isolates amplified from cell cultures and the Insavc strain retrieved from GenBank. In the sake of simplicity, the recombinant FCoV type II strains 79-1146 and 79-1163 are also indicated by their initials.

4. Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the extent of genetic diversity among the CCoVs circulating in Italy and to examine their relationships to strains characterized previously. Although our findings are based on a number of samples that is too small to yield firm conclusions, they provide however evidence that the circulating CCoVs in Italy segregate into two separate groups. Interestingly, in the M and pol1b-region D trees the outlier samples were related closely to each other and formed a single phylogroup. Pairwise genetic distances as estimated from multiple nucleotide alignments of these sequences together with those of other reference isolates readily allowed to distinguish the different genotypes, indicating that the fragments analyzed contained sufficient information to characterize the coronavirus-positive samples. The overall nucleotide divergence, shown in Table 4 , showed that Italian samples were highly heterogeneous with distance values that were not dissimilar from those found between CCoV and FCoV isolates. The matrix of pairwise genetic distances showed that most Italian samples were closely related to the CCoV genotype but the C27/3, 74/99B, 74/99C, A32/99, 79/99, 259/01 and 107/99 samples clearly differed from the others, as they exhibited high distance values from the other Italian isolates and from the reference genotype CCoV isolates (data not shown) and have been therefore tentatively called FCoV-like CCoVs. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that under natural conditions homologous recombination events between highly homologous coronaviruses, such as CCoV and FCoV, occur very frequently. This means that there is a frequent interspecific circulation of either CCoV to cats or FCoV to dogs since mixed infections are required to give rise to recombination. Where the recombination takes place is unknown, but under experimental conditions cats can be infected with CCoV (Barlough et al., 1984, Stoddart et al., 1988, McArdle et al., 1990, McArdle et al., 1992) and, although it has not been demonstrated that FCoV may infect dogs cannot be ruled out. According to this hypothesis, restricted sites of recombination (i.e. regions of very high nucleotide identity between two highly homologous coronaviruses) may exist in the genome of coronaviruses and these sites may readily undergo template switches. This explanation assumes that coronaviruses of domestic carnivores possess a sort of ‘dynamic’ genome. However, the presence of numerous synapomorphic (shared–derived) signals allowing segregation of outlier FCoV-like CCoVs samples in a single phylogroup, in the M gene and pol1b-region D is compatible with the idea that these samples diverged at approximately the same time from an ancient common ancestor and subsequently underwent independent evolutions. This hypothesis is also consistent with the appreciable variations detected throughout the fragments of the pol1a and pol1b of FCoV-like CCoVs as compared to typical CCoVs. Considerable nucleotide variations, affecting the reliability of a CCoV diagnostic test (nested-PCR), have been already described in a fragment of the M gene of some CCoV strains (Pratelli et al., 2001b).

Table 4.

Nucleotide variations among CCoVs and FCoVs

| Typical CCoVs |

FCoV-like CCoVs |

FCoVs |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | A | B | C | D | M | A | B | C | D | M | A | B | C | D | |

| 4.98 | 5.75 | 5.49 | 2.75 | 2.00 | 11.74 | 9.31 | 7.27 | 5.15 | 7.86 | 17.51 | 19.74 | 16.21 | 12.62 | 13.64 | Typical CCoVs |

| 7.02 | 8.82 | 10.19 | 5.54 | 3.28 | 15.93 | 19.25 | 16.48 | 12.08 | 11.41 | FCoV-like CCoVs | |||||

| 5.06 | 6.68 | 4.41 | 3.50 | 4.00 | FCoVs | ||||||||||

Values indicate the arithmetic average x extrapolated from the nucleotide matrix of comparison and are expressed in %. M, M gene. A, 320 bp fragment of the ORF1a. B, 389 bp fragment of the ORF1a. C, 749 bp fragment of the ORF1b. D, 472 bp fragment of the ORF1b. Due to recombination events affecting the genome of FCoVs type II, the values referred to strains 79-1683 and 79-1146 were not considered in C and D.

Interestingly, sequence analysis on the whole M protein of CCoVs revealed a high amino acid variability in the amino-terminal end which is exposed on the outside of the virion according to the topological model proposed by Risco et al. (1995); whereas in the sequence of the transmembrane and of the carboxyl-terminal domains there were only a few scattered substitutions (Fig. 2) and most of the substitutions occurring in the M protein of FCoV-like CCoVs were similar to residues typical of FCoV. Although the major immunological role has been attributed to the S protein, both the amino- and the carboxy-termini of the M protein of coronavirus elicit a strong immune response (Enjuanes et al., 2000a). Therefore, the variations observed in the M protein might confer new functions and/or properties to the virus resulting in survival advantages, such as escape from the immune system.

Comparative analysis on other genomic fragments of CCoVs will help to elucidate the evolution and relationships between coronaviruses in domestic carnivores, whereas studies on the antigenic correlations between ‘typical’ and ‘atypical’ CCoVs will provide insight into the biological role and pathogenesis of FCoV-like CCoVs. Large molecular surveys will be necessary to determine the real prevalence and divergence from classical genotypes of the outlier samples. These data will be helpful to discern whether FCoV-like CCoVs belong to a new, unrecognized, coronavirus genotype.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from CEGBA (Centro di Eccellenza di Genomica in Campo Biomedico e Agrario) and from Ministry of University, Italy (project: Enteriti virali del cane).

References

- Almazan F., Gonzales J.M., Penzes Z., Izeta A., Calvo E., Plana-Duran J., Enjuanes L. Engineering the largest RNA virus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5516–5521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel M.J., Cooper B.J., Greisen H., Scott F., Carmichael L.E. Canine viral enteritis. I. Status report on corona- and parvo-like viral enteritides. Cornell Vet. 1979;69:123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandai C., Ishiguro S., Masuya N., Hohdatsu T., Mochizuki M. Canine coronavirus infections in Japan: virological and epidemiological aspects. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1999;61:731–736. doi: 10.1292/jvms.61.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlough J.E., Stoddart C.A., Sorresso G.P., Jacobson R.H., Scott F.W. Experimental inoculation of cats with canine coronavirus and subsequent challenge with feline infectious peritonitis virus. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1984;34:592–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonavoglia, C., Marsilio, F., Cavalli, A., Tiscar, P.G., 1994. L'infezione da coronavirus del cane: indagine sulla presenza del virus in Italia. Not. Farm. Vet. Nr. 2/94, ed. SCIVAC.

- Cooper P.D., Steiner-Pryor S., Scotti P.D., Delong D. On the nature of poliovirus genetic recombinants. J. Gen. Virol. 1974;23:41–49. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-23-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot R.J., Maduro J., Lenstra J.A., Horzinek M.C., van der Ziejst B.A.M., Spaan W.J.M. cDNA cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding the peplomer protein of feline infectious peritonitis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1987;68:2639–2646. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-10-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan C.A., Vennema H., Rottier P.J. Assembly of the coronavirus envelope: homotypic interactions between the M proteins. J. Virol. 2000;74:4967–4978. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.4967-4978.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries A.A.F., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J.M., de Groot R.J. The genome organization of the Nidovirales: similarities and differences between arteri-, toro-, and coronaviruses. Semin. Virol. 1997;8:33–47. doi: 10.1006/smvy.1997.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolja V.V., Carrington J.C. Evolution of positive-strand RNA viruses. Semin. Virol. 1992;3:315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Enjuanes L., Brian D., Cavanagh D., Holmes K., Lai M.M.C., Laude H., Masters P., Rottier P., Siddell S., Spaan W.J.M., Taguchi F., Talbot P. Coronaviridae. In: van Regenmortel M.H.V., Fauquet C.M., Bishop D.H.L., Carstens E.B., Estes M.K., Lemon S.M., Maniloff J., Mayo M.A., McGeoch D.J., Pringle C.R., Wickner R.B., editors. Virus Taxonomy, Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Academic Press; New York: 2000. pp. 835–849. [Google Scholar]

- Enjuanes L., Spaan W., Snijder E., Cavanagh D. Nidoviridales. In: van Regenmortel M.H.V., Fauquet C.M., Bishop D.H.L., Carstens E.B., Estes M.K., Lemon S.M., Maniloff J., Mayo M.A., McGeoch D.J., Pringle C.R., Wickner R.B., editors. Virus Taxonomy, Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Academic Press; New York: 2000. pp. 827–834. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer F., Posthumus W.A.P., Correa I., Suné C., Sánchez C.M., Smerdou C., Lenstra J.A., Meloen R., Enjuanes L. Residues involved in the formation of the antigenic sites of the S protein of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus. Virology. 1991;183:225–238. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90135-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh A.A.P.M., de Groot R.J., Cepica A., Egberink H.F., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J.M. Detection of feline coronavirus RNA in feces, tissue, and body fluid of naturally infected cats by reverse transcriptase PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33:684–689. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.684-689.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh A.A.P.M., Smeenk I., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J.M., de Groot R.J. Feline coronavirus type II strains 79-1683 and 79-1146 originate from a double recombination between feline coronavirus type I and canine coronavirus. J. Virol. 1998;72:4508–4514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4508-4514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohdatsu T., Okada S., Koyama H. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against feline infectious peritonitis virus type II and antigenic relationship between feline, porcine, and canine coronavirus. Arch. Virol. 1991;117:85–95. doi: 10.1007/BF01310494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohdatsu T., Okada S., Ishizuka Y., Yamada H., Koyama H. The prevalence of types I and II feline coronavirus infections in cats. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1992;54:557–562. doi: 10.1292/jvms.54.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsburgh B.C., Brierley I., Brown T.D. Analysis of a 9.6 kb sequence from the 3′ end of canine coronavirus genomic RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 1992;73:2849–2862. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-11-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis T.C., Kirkegaard K. The polymerase in its labyrinth: mechanisms and implications of RNA recombination. Trends Genet. 1991;7:186–191. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90434-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W., Karaka K., Parrish C.R., Naqi S.A. A novel variant of infectious bronchitis virus resulting from recombination among three different strains. Arch. Virol. 1995;140:259–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01309861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck J.G., Matsushima G.K., Makino S., Fleming J.O., Vannier D.M., Stohlman S.A., Lai M.M.C. In vivo RNA–RNA recombination of coronavirus in mouse brain. J. Virol. 1988;62:1810–1813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1810-1813.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkegaard K., Baltimore D. The mechanism of RNA recombination in poliovirus. Cell. 1986;47:433–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottier S.A., Cavanagh D., Britton P. Experimental evidence of recombination in coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. Virology. 1995;213:569–580. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo L., Godeke G.J., Raamsman M.J., Masters P.S., Rottier P.J. Retargeting of coronavirus by substitution of the spike glycoprotein ectodomain: crossing the host cell species barrier. J. Virol. 2000;74:1393–1406. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1393-1406.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusters J.G., Jager E.J., Niesters H.G.M., Zeist B.A.M. Sequence evidence for RNA recombination in field isolates of avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. Vaccine. 1990;8:605–608. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(90)90018-H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M.C., Baric R.S., Makino S., Keck J.G., Egbert J., Leibowitz J.L., Stohlman S.A. Recombination between nonsegmented RNA genomes of murine coronaviruses. J. Virol. 1985;56:449–456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.2.449-456.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M.C., Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luytjes W. Coronavirus gene expression: genome organization and protein expression. In: Siddell S.G., editor. The Coronaviridae. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Makino S., Keck J.G., Stohlman S.A., Lai M.M.C. High-frequency RNA recombination of murine coronavirus. J. Virol. 1986;57:729–739. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.729-737.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin H.D., Zeidner N.S. Concomitant cryptosporidia, coronavirus and parvovirus infection in a raccoon (Procyon lotor) J. Wildl. Dis. 1992;28:113–115. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle F., Bennett M., Gaskell R.M., Tennant B., Kelly D.F., Gaskell C.J. Canine coronavirus infection in cats; a possible role in feline infectious peritonitis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1990;276:475–479. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5823-7_66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle F., Bennett M., Gaskell R.M., Tennant B., Kelly D.F., Gaskell C.J. Induction and enhancement of feline infectious peritonitis by canine coronavirus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1992;53:1500–1506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motokawa K., Hohdatsu T., Hashimoto H., Koyama H. Comparison of the amino acid sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the peplomer, integral membrane and nucleocapsid proteins of feline canine and porcine coronaviruses. Microbiol. Immunol. 1996;40:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor M.J., Harrison G.A., Monckton R.P., McOrist S., Lehrbach P.R., Deane E.M. Identification of canine coronavirus strains from feces by S gene nested PCR and molecular characterization of a new Australian isolate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39:1036–1041. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.1036-1041.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli A., Buonavoglia D., Martella V., Cavalli A., Lavazza, Buonavoglia C. Enteriti virali del cane: risultati di un'indagine virologica. Veterinaria. 1999;13:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli A., Tempesta M., Greco G., Martella V., Buonavoglia C. Development of a nested PCR for the detection of canine coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods. 1999;80:11–15. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli A., Buonavoglia D., Martella V., Tempesta M., Lavazza A., Buonavoglia C. Diagnosis of canine coronavirus infection using nested-PCR. J. Virol. Methods. 2000;84:91–94. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00134-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli A., Martella V., Elia G., Tempesta M., Guarda F., Capucchio M.T., Carmichael L.E., Buonavoglia C. Severe enteric disease in an animal shelter associated with dual infections by canine adenovirus type 1 and canine coronavirus. J. Vet. Med. B. 2001;48:385–392. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2001.00466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli A., Martella V., Elia G., Decaro N., Aliberti A., Buonavoglia D., Tempesta M., Buonavoglia C. Variation of the sequence in the gene encoding for transmembrane protein M of canine coronavirus (CCV) Mol. Cell Probes. 2001;15:229–233. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2001.0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raamsman M.J.B., Locker J.K., de Hooge A., de Vries A.A.F., Griffiths G., Vennema H., Rottier P.J.M. Characterization of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus strain A59 small membrane protein E. J. Virol. 2000;74:2333–2342. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2333-2342.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risco C., Antón I.M., Sune C., Pedregosa A.M., Martín-Alonso J.M., Parra F., Carrascosa J.L., Enjuanes L. Membrane protein molecules of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus also espose the carboxy-terminal region on the external surface of the virion. J. Virol. 1995;69:5269–5277. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5269-5277.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottier P.J.M. The coronavirus membrane protein. In: Siddell S.G., editor. The Coronaviridae. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C.M., Izeta A., Sanchez-Morgado J.M., Alonso S., Sola I., Balasch M., Plana-Duran J., Enjuanes L. Targeted recombination demonstrates that the spike gene of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus is a determinant of its enteric tropism and virulence. J. Virol. 1999;73:7607–7618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7607-7618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddell S.G. The coronaviridae, an introduction. In: Siddell S.G., editor. The Coronaviridae. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart C.A., Barlough J.E., Baldwin C.A., Scott F.W. Attempted immunisation of cats against feline infectious peritonitis using canine coronavirus. Res. Vet. Sci. 1988;45:383–388. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5288(18)30970-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennema H., Poland A., Floyd Hawkins K., Pedersen N.C. A comparison of the genomes of FECVs and FIPVs and what they tell us about the relationships between feline coronaviruses and their evolution. Feline Pract. 1995;23:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Junker D., Collisson E.W. Evidence of natural recombination within the S1 gene of infectious bronchitis virus. Virology. 1993;192:710–716. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods R.D., Wesley R.D., Kapke P.A. Complement-dependent neutralization of transmissible gastroenteritis virus by monoclonal antibodies. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1987;218:493–500. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-1280-2_64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasoshima A., Fujinami F., Doi K., Kojima A., Takada H., Okaniwa A. Case report on mixed infection of canine parvovirus and canine coronavirus—electron microscopy and recovery of canine coronavirus. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi. 1983;45:217–225. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.45.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]