Abstract

A diagnostic test for canine coronavirus (CCV) infection based on a nested polymerase chain reaction (n-PCR) assay was developed and tested using the following coronavirus strains: CCV (USDA strain), CCV (45/93, field strain), feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV, field strain), trasmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV, Purdue strain), bovine coronavirus (BCV, 9WBL-77 strain), infectious bronchitis virus (IBV, M-41 strain) and fecal samples of dogs with CCV enteritis. A 230-bp segment of the gene encoding for transmembrane protein M of CCV is the target sequence of the primer. The test described in the present study was able to amplify both CCV and TGEV strains and also gave positive results on fecal samples from CCV infected dogs. n-PCR has a sensitivity as high as isolation on cell cultures, and can therefore be used for the diagnosis of CCV infection in dogs.

Keywords: Canine coronavirus, Dogs, Nested-polymerase chain reaction

1. Introduction

Canine coronavirus (CCV) is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Coronaviridae family and is responsible for mild to severe gastroenteritis in dogs (Binn et al., 1974; Appel, 1987). Infected dogs shed CCV in feces for 6–9 days (Keenan et al., 1976) but shedding can be prolonged in some pups. The virus content of feces is very high at the time clinical signs first appear (Appel, 1987).

Electron microscopic (EM) examination of negatively stained fecal suspensions or viral isolation in cell cultures are the most commonly used methods for the diagnosis of CCV infection in dogs. Both of those methods are time-consuming, however, and EM is not available in many laboratories and may produce artifacts. Because it is sometimes difficult to differentiate CCV infection from infection caused by the more virulent canine parvovirus, it is important to be able to obtain a rapid etiological diagnosis in kennels experiencing an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis.

Recently a nested polymerase chain reaction (n-PCR) assay was developed for detection of feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), a coronavirus closely related to CCV, in clinical specimens (Gamble et al., 1997). The present report describes the development of a n-PCR for the diagnosis of canine coronavirus infection. The n-PCR procedure was chosen because it is more sensitive and specific than tests which employ a single target sequence (Porter-Jordan et al., 1990).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. RT–PCR

The target sequence for amplification was a segment of the gene encoding for the transmembrane protein M of CCV. The above sequence, comprising 409 bp, straddles nucleotides 337 and 746, as described by Herrewegh et al. (1998).

The following primers were prepared:CCV1: 5′-TCC AGA TAT GTA ATG TTC GG-3′ sense primer (337–356 nucleotides);CCV2: 5′-TCT GTT GAG TAA TCA CCA GCT-3′ antisense primer (726–746 nucleotides);CCV3: 5′-GGT GTC ACT CTA ACA TTG CTT-3′ internal primer (535–556 nucleotides).

The cDNA was synthesized in a 20 μl total reaction volume containing 2.5 μl of RNA, PCR buffer 10× (KCl 500 mM, Tris–HCl 100 mM, pH 8.3), 25 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mM of each dNTP, 20 U/μl RNasi, 50 U/μl RT, 0.6 μg/μl CCV2 primer. The cDNA was synthesized at 37°C for 30 min with the final stage at 94°C for 5 min.

PCR was undertaken in 100 μl volumes in a mixture containing PCR buffer 10×, 25 mM MgCl2, 2 mM of each dNTP, 5U Amplitaq Gold DNA polymerase, and 1.2 μg/μl of CCV1 primer. The amplification reaction was carried out in a DNA Thermal Cycler (Perkin Elmer Cetus, USA) for 34 cycles with denaturation at 94°C for 1 min., annealing at 55°C for 1 min. and polymerization at 72°C for 3 min. All reactions were preceded by an activation phase of Amplitaq Gold at 94°C for 10 min. A 8-μl aliquot of the amplified product was then visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis (2% agarose, 50 V for 120 min) and subsequent UV transillumination after ethidium bromide staining. For the n-PCR, a 20-μl aliquot of the 1:100 dilution of the first amplicon was subjected to a second round of amplification using the CCV2 and CCV3 primers and the same cycling procedures.

2.2. Coronavirus strains

The PCR and n-PCR trials were carried out on the following CCV strains: ‘USDA strain’ and strain 45/93, that was isolated from a dog with enteritis (Buonavoglia et al., 1994). Four additional coronaviruses were also examined: FIPV, isolated from a cat with infectious peritonitis (Buonavoglia et al., 1995); porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), Purdue strain; bovine coronavirus (BCV), strain 9WBL-77; infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), strain M-41.

2.3. Clinical specimens

The PCR and n-PCR were carried out on fecal samples from six dogs with enteritis. EM examinations were previously carried out on only fecal samples from two dogs and typical coronavirus particles were demonstrated. Fecal samples from two normal dogs were included as controls.

2.4. Genome RNA extraction

Genomic RNA was extracted from the cryolysate of cell cultures infected with the examined coronavirus strains, using the RNeasy Total RNA kit (Qiagen GmbH Germany). Similar preparations were made from the 1:100 dilution of the fecal samples.

2.5. PCR sensitivity

Serial 10-fold dilutions of CCV strain 45/93 were inoculated into monolayer cultures of A-72 cells and those dilutions were used for both PCR and n-PCR. The virus titre was calculated 4 days after infection, assaying for median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) by typical viral cytopathic effects.

3. Results

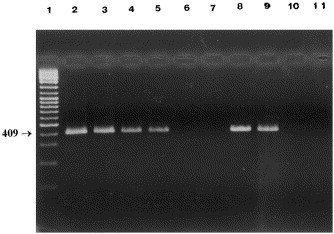

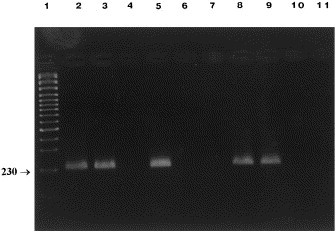

As shown (Fig. 1 ), CCV1 and CCV2 primers specific for the target sequence of M gene generated, as expected, a 409 bp amplified product with the following viral strains: CCV USDA, CCV 45/93, FIPV and TGEV, but not with BCV and IBV. CCV2 and CCV3 primers used for n-PCR generated a 230 bp amplicon in the same coronavirus strains amplified by the first PCR, with the exception of FIPV (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

PCR products (409 bp) of different coronavirus strains using CCV1-CCV2 primers. Lane 1, marker (Gene RulerTM 100 bp DNA Ladder Plus, Fermentas); lane 2, CCV USDA; lane 3, CCV 45/93; lane 4, FIPV; lane 5, TGEV Purdue; lane 6, BCV 9WBL-77; lane 7, IBV M-41; lane 8, fecal sample CCV positive; lane 9, fecal sample CCV positive; lane 10, fecal sample CCV negative; lane 11, fecal sample CCV negative.

Fig. 2.

n-PCR products (230 bp) of different coronavirus strains using CCV2-CCV3 primers. Lane 1, marker (Gene RulerTM 100 bp DNA Ladder Plus, Fermentas); lane 2, CCV USDA; lane 3, CCV 45/93; lane 4, FIPV; lane 5, TGEV Purdue; lane 6, BCV 9WBL-77; lane 7, IBV M-41; lane 8, fecal sample CCV positive; lane 9, fecal sample CCV positive; lane 10, fecal sample CCV negative; lane 11, fecal sample CCV negative.

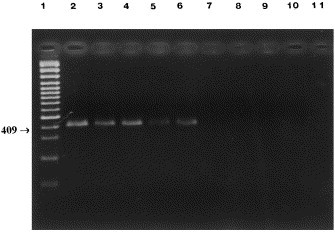

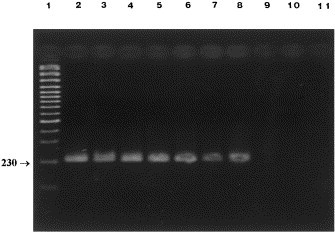

The CCV infectious titer in A-72 cells was 105.75 TCID50, whereas the detection limit by PCR was the 10−4 dilution (Fig. 3 ). Using the same virus dilutions, the genomic RNA was detected by n-PCR up to the 10−6 dilution (Fig. 4 ). The PCR carried out on fecal samples gave positive results for three of the six diarroheic specimens. Two of three samples PCR-positive, previously resulted positive in EM examinations. The fecal samples from normal dogs consistently gave negative results.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity of PCR on log10 dilutions of CCV: amplified products of 409 bp using CCV1 and CCV2 primers. Lane 1, marker (Gene RulerTM 100 bp DNA Ladder Plus, Fermentas); lanes 2–9, undiluted, 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, 10−6, 10−7.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity of n-PCR on log10 dilutions of CCV: amplified products of 230 bp using CCV2 and CCV3 primers. Lane 1, marker (Gene RulerTM 100 bp DNA Ladder Plus, Fermentas); lanes 2–9, undiluted, 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, 10−6, 10−7.

The n-PCR gave positive results for four of the six diarroheic fecal samples, whereas the samples from normal dogs gave negative results.

4. Discussion

PCR carried out with CCV1 and CCV2 primers specific for the target sequence 337–746 of M gene revealed high sensitivity; tests performed on corresponding viral dilutions, which also were inoculated into cell cultures, gave positive results to the 10−4 dilution (approximately 10–50 TCID50 of virus). When viral titrations in cell culture were compared with PCR and n-PCR results, the n-PCR was found to be the most sensitive, giving positive reactions up to the 10−6 virus dilution.

The higher sensitivity of n-PCR was also evident in assays carried out on dog fecal samples. In regard to the specificity of the n-PCR, the primers CCV1 and CCV2 were able to amplify the M gene segment of CCV, FIPV and TGEV genomes, but not the M gene segment of IBV and BCV. This is expected because CCV, FIPV and TGEV are closely related (Horsburgh et al., 1992). n-PCR, with the primers CCV2 and CCV3, amplified both CCV and TGEV genomes, but not that of FIPV, thus revealing higher specificity than the conventional PCR.

The PCR and n-PCR assays described in the present study revealed a relatively low specificity with respect to the amplification of the gene segments of the different coronaviruses studied, i.e. CCV, FIPV and TGEV by PCR; CCV and TGEV by n-PCR. However, this limit does not restrict the use of either method in routine laboratory diagnostic tests.

Our principal interest was to develop both PCR and n-PCR as methods to rapidly differentiate CCV infections from other canine enteric pathogens which cause similar clinical illness. The diagnosis of CCV enteritis would be more rapid with the PCR assay than with virus isolation in cell cultures, and would obviate the need for EM, which may provide spurious results. Moreover, the PCR test allows the detection of denatured CCV in fecal samples.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr Donato Narcisi for his excellent technical assistance.

References

- Appel, M.J., 1987. Canine coronavirus. In: Appel, M.J. (Ed), Virus infections of carnivores. Horzinek, M.C. (Series Ed.) Virus infections of vertebrates. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, pp. 115–122.

- Binn L.N., Lazar E.C., Keenan K.P., Huxsoll D.L., Marchwicki B.S., Strano A.J., 1974. Recovery and characterization of a coronavirus from military dogs with diarrhea. Proc. 78th Ann. Mtg. USAHA, 359–366. [PubMed]

- Buonavoglia, C., Marsilio, F., Cavalli, A., Tiscar, P.G., 1994. L'infezione da coronavirus del cane: indagine sulla presenza del virus in Italia. Notiziario Farmaceutico Veterinario, Nr. 2/94, ed. SCIVAC.

- Buonavoglia C., Sagazio P., Cirone F., Tempesta M., Marsilio F. Isolamento e caratterizzazione di uno stipite di virus della peritonite infettiva felina. Veterinaria Anno. 1995;9(1):91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble D.A., Lobbiani A., Gramegna M., Moore L.E., Colucci G. Development of a nested PCR assay for detection of feline infectious peritonitis virus in clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35:673–675. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.673-675.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh A.A., Smeenk I., Horzinek M.C., Rottier P.J.M., de Groot R.J. Feline coronavirus type II strains 79-1683 and 79-1146 originate from a double recombination between feline coronavirus type I and canine coronavirus. J. Virol. 1998;72(5):4508–4514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4508-4514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsburgh B.C., Brierley I., Brown T.D. Analysis of a 9.6 Kb sequence from the 3′-end of canine coronavirus genomic RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 1992;73:2849–2862. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-11-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K.P., Jervis H.R., Marchwicki R.H., Binn L.N. Intestinal infection of neonatal dogs with canine coronavirus 1-71: studies by virologic, histochemical and immunofluorescent techiques. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1976;37(3):247–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter-Jordan K., Rosenberg E.I., Keiser J.F., Gross J.D., Ross A.M., Nasim S., Garret C.T. Nested polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of cytomegalovirus overcomes false positives caused by contamination with fragmented DNA. J. Med. Virol. 1990;30:85–91. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]