Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of the current management and treatment of hospital wastewater in Asia, Africa, and Australia. Twenty peer reviewed papers from different countries have been analyzed, highlighting the rationale behind each study and the efficacy of the investigated treatment in terms of macro- and micro-pollutants. Hospital wastewaters are subjected to different treatment scenarios in the studied countries (specific treatment, co-treatment, and direct disposal into the environment). Different technologies have been adopted acting as primary, secondary, and tertiary steps, the most widely applied technology being conventional activated sludge (CAS), followed by membrane bioreactor (MBR). Other types of technology were also investigated. Referring to the removal efficiency of macro- and micro-pollutants, the collected data demonstrates good removal efficiency of macro-pollutants using the current adopted technologies, while the removal of micro-pollutants (pharmaceutical substances) varies from low to high removal and release of some compounds was also observed. In general, there is no single practice which could be considered a solution to the problem of managing HWWs – in many cases a number of sequences are used in combination.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistant bacteria, Hospital wastewater, Pharmaceuticals, Removal efficiency, Wastewater treatment

Introduction

Hospital wastewater (HWW) is the wastewater discharged from all hospital activities, both medical and non-medical, including activities in surgery rooms, examination rooms, laboratories, nursery rooms, radiology rooms, kitchens, and laundry rooms. Hospitals consume consistent quantities of water per day. The consumption in hospitals in industrialized countries varies from 400 to 1,200 L per bed per day [1], whereas in developing countries this consumption seems to be between 200 and 400 L per bed per day [2].

HWWs are considered of similar quality to municipal wastewater [3, 4], but may also contain various potentially hazardous components which mainly include hazardous chemical compounds, heavy metals, disinfectants, and specific detergents resulting from diagnosis, laboratory, and research activities [5–9]. Higher concentrations of pharmaceutical compounds (PhCs) were found in hospital effluents than those found in municipal effluents [10, 11]. According to recent literature [8, 12–14], HWWs may be considered a hot spot in terms of the PhC load generated, prompting the scientific community to question the acceptability of the general practice of discharging HWWs into public sewers [8], where they are conveyed to municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and co-treated with urban wastewaters (UWWs) [8, 13, 15, 16].

HWWs represent an important source of PhCs detected in all WWTP effluents, due to their inefficient removal in the conventional systems [17–20]. Indeed, HWWs may have an adverse impact on environmental and human health through the dissemination of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria in rivers [21–24]. The correct management, treatment, and disposal of HWWs are therefore of increasing international concern.

In European countries efforts are being made to improve the removal of PhCs by means of end-of-pipe treatments, and different full scale WWTPs have already been constructed for the specific treatment of hospital effluents [25].

In order to highlight this area of research in the rest of the world, this chapter provides an overview of the current management and treatment of HWWs in Asia, Africa, and Australia.

Treatment Scenarios of HWWs

Different treatment scenarios are applied in different countries for the treatment of HWWs. Table 1 lists all the treatment scenarios applied, with the corresponding references. Hospital effluents are usually discharged into the urban sewer system, where they mix with other effluents before finally being treated in the sewage treatment plant (co-treatment). This practice is common in Australia, Iran, Egypt, India, Japan, South Africa, and Thailand. However, in many other developing countries, such as Algeria, Bangladesh, Congo, Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Taiwan, and Vietnam, hospital effluents can represent a major source of toxic elements in the aquatic environment since the effluents are discharged into drainage systems, rivers, and lakes without prior treatment. According to Ashfaq et al. [41], no hospital, irrespective of its size, has installed proper wastewater treatment facilities in Pakistan. In Taiwan, some hospitals discharge their wastewaters (legally or illegally) directly into nearby rivers with scarce treatment at all [44]. Of 70 governmental hospitals from different provinces of Iran, 48% were equipped with wastewater treatment systems, while 52% were not. Fifty-two percent of the hospitals without treatment plants disposed their raw wastewater into wells, 38% disposed it directly into the environment and the rest into the municipal wastewater network [35]. Comparison of the indicators between effluents of wastewater treatment systems and the standards of Environmental Departments shows the inefficiency of these systems and, despite recent improvements in hospital wastewater treatment systems, they should be upgraded.

Table 1.

Treatment scenarios of hospital effluents in different countries

| Country | Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Algeria | Direct disposal into the environment | [26] |

| Australia | Co-treatment | [14, 27] |

| Bangladesh | Direct disposal into the environment | [23] |

| China | Specific treatment | [10, 28–30] |

| Congo | Direct disposal into the environment | [31] |

| Egypt | Co-treatment | [4] |

| Ethiopia | Direct disposal into the environment | [32] |

| India | Direct disposal into the environment/co-treatment/specific treatment | [11, 31, 33] |

| Indonesia | Specific treatment/direct disposal into the environment | [34] |

| Iran | Specific treatment/co-treatment | [3, 35–37] |

| Iraq | Specific treatment | [38] |

| Japan | Co-treatment | [39] |

| Nepal | Direct disposal into the environment | [40] |

| Pakistan | Direct disposal into the environment | [21, 41] |

| Republic of Korea | Specific treatment | [42] |

| South Africa | Co-treatment | [43] |

| Taiwan | Direct disposal into the environment | [44] |

| Thailand | Co-treatment | [45] |

| Vietnam | Direct disposal into the environment | [6] |

In Indonesia, only 36% of hospitals have a WWTP and 64% of wastewater is discharged directly into receiving water bodies or using infiltration wells. Mostly, Hospital Wastewater Treatment Plants (HWWTP) use a combination of biological-chlorination processes with the discharge often exceeding the quality standard, such as Pb, phenol, ammonia free, ortho-phosphate, and free chlorine. The low quality of discharges into HWWTPs, especially of toxic pollutants (Pb and phenol), can be caused by not yet optimal biological-chlorination process [34].

An interesting investigation was carried out in 2004 in Kunming city, a large city in the southwest of China. Of 45 hospitals there were 36 with wastewater disinfection equipment. In the same year, the wastewater treatment facilities of 50 hospitals were investigated in Wuhan city, which is the biggest city in the central southern part of China. It showed that there were 46 hospitals with wastewater treatment facilities, and for only about 50% of them, the effluent quality from wastewater treatment facilities accorded with the national discharge standard [29, 46, 47].

In Iraq, most of the hospitals have their own treatment plant, but they are not capable of meeting Iraqi standards, especially in terms of nutrient and pathogen removal [38]. The scenario of hospital wastewater treatment is more stringent in countries like China, Indonesia, and the Republic of Korea, where HWW is treated onsite (specific treatment).

An effective, robust, and relatively low-cost treatment was used to disinfect HWWs during Haiti cholera outbreak occurred after the earthquake of January 2010. Two in-situ protocols were adopted: Protocol A included coagulation/flocculation and disinfection with hydrated (slaked) lime (Ca(OH)2) by exposure to high pH and Protocol B using hydrochloric acid followed by pH neutralization and subsequent coagulation/flocculation, using aluminum sulfate. This approach is currently being adapted by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to help managing human excreta in other emergency settings, including the outbreaks of Ebola and other infectious diseases in west Africa, Philippines, and Myanmar [48].

Overview of the Included Studies

The main characteristics of the studies included in this chapter referring to the specific treatment of hospital effluents are reported in Table 2. The main reason for research in European countries is generally an awareness of the potential risks posed by the occurrence of PhC residues in secondary effluents and the need to reduce the PhC load discharged into the environment via WWTP effluents [25]. However, the rationale behind the studies presented in this chapter was to evaluate different options for hospital effluent treatments before discharge into public sewage or into the environment, to improve the biodegradability of hospital effluents, to avoid the spread of pathogenic microorganisms, viruses, antibiotic resistant bacteria, pharmaceuticals, and chemical pollutants, to reduce the organic load and finally, to meet the requirements of discharge standards in different countries. Of all the studies, only four deal with the occurrence of PhCs in hospital effluents, while the remaining studies take into consideration pathogenic bacteria and conventional pollutants like COD, BOD, and SS.

Table 2.

List of the studies included in the overview together with a brief description of the corresponding investigations and rationale

| Reference | Main characteristics of experimental investigations and treatment plants | Rationale | Investigated parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| [6] | Investigation into the occurrence and behavior of fluoroquinolone antibacterial agents (FQs) in HWWs in Hanoi, Vietnam. A specific hospital CAS treatment plant was also investigated for the removal of FQs | The potential environmental risks and spread of antibacterial resistance among microorganisms | Ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin |

| [10] | Investigation carried out in Beijing (China) for the quantification of 22 common psychiatric pharmaceuticals and their removal in two psychiatric hospital WWTPs (CAS) | Potential impact of PhCs on ecosystems and human health | 22 psychiatric pharmaceuticals |

| [11] | Investigation undertaken to identify the presence and removal of selected PCs in four STPs located in South India. The treatment process that treats HWWs is an extended aeration activated sludge process | The risk associated with the presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment | 7 PhCs |

| [17] | Investigation carried out at the hospital located in Vellore, Tamil Nadu (India), by means of a lab-scale plant consisting of coagulation (by adding FeCl3 up to 300 mg/L), rapid filtration, and disinfection (by adding a bleaching powder solution) steps | Options for hospital effluent pretreatment before discharge into public sewage | Conventional parameters: COD, BOD5, SS, and P |

| [35] | Investigation carried out in Iran to analyze the hospital wastewater treatment system of 70 governmental hospitals from different provinces | Control of the discharge of chemical pollutants and active bacteria contained in hospital wastewater | Conventional parameters: TSS, BOD5, COD |

| [34] | Investigation on a pilot-scale plant consisting of an aerated fixed film biofilter (AF2B reactor) coupled with an ozonation reactor fed by the effluent from Malang City hospital in Indonesia | Pollution and health problems for humans being caused by the discharge of HWWs | Conventional pollutants: BOD, phenols, fecal coliform, and Pb |

| [28] | Investigation carried out at Haidian community hospital (China), where a full scale submerged hollow fiber MBR was installed | Efficiency and operation stability of MBR equipped with microfiltration membranes in treating HWWs | Monitored pollutants were COD, BOD5, NH4, turbidity, and Escherichia coli |

| [29] | Investigation carried out in China on the operating conditions and MBR efficiency in treating hospital effluents | Attempts to avoid the spread of pathogenic microorganisms and viruses, especially following the outbreak of SARS in 2003 | Conventional parameters: COD, BOD5, NH3, TSS, bacteria, and fecal coliform |

| [30] | A combination process of biological contact oxidation, MBR, and sodium hypochlorite disinfectants was applied to treat HWWs in Tianjin (China) | To meet the requirements of the Chinese discharge standards of water pollution for medical organizations | Conventional parameters: SS, BOD5, COD, NH3, total coliforms, fecal coliform |

| [40] | Analysis of the removal performance in a full scale two stage constructed wetland (CW) designed and constructed in Nepal to treat hospital effluent (20 m3/d). The system consists of a three chambered septic tank, a horizontal flow bed (140 m2), with 0.65–0.75 m depth, and a vertical flow bed (120 m2) with 1 m depth. The beds were planted with local reeds (Phragmites karka) | Transferring CW technology to developing countries to reduce pollution in aquatic environments | Conventional parameters: TSS, BOD5, COD, NH4, PO4 2−, total coliforms, E. coli, streptococci |

| [42] | Investigation carried out at two hospital WWTPs located in Korea to assess the occurrence and removal of selected pharmaceutical and personal care products. The wastewater treatment plants consist of (1) flocculation (FL) + activated carbon filtration (AC); (2) flocculation + CAS | Potential risks of anthelmintics on non-target organisms in the environment and their resistance to biodegradation | 33 pharmaceutical and personal care products |

| [45] | Investigation carried out in Bangkok, Thailand, on the pretreatment of hospital effluents by using a lab-scale photo-Fenton process | Improvement in the biodegradability of hospital effluents by using the photo-Fenton process as a pretreatment | Conventional parameters: COD, BOD5, TOC, turbidity, TSS, conductivity, and toxicity |

| [49] | Investigation carried out in Taiwan on the disinfection by continuous ozonation of the hospital effluent and in particular of the effluent from the kidney dialysis unit and on the increment of hospital effluent biodegradability | Disinfection effect and improvement in biodegradability of hospital effluent by ozonation | Conventional parameters: COD, BOD, total coliforms |

| [50] | Investigation carried out in India on a pilot plant consisting of preliminary and primary treatments, a conventional activated sludge system, sand filtration, and chlorination | Investigation into the microbiological community and evaluation of the risk of multidrug resistant bacteria spread | Different microbiological parameters: total coliforms, fecal enterococci, staphylococci, Pseudomonas, multidrug resistant bacteria |

| [51] | Analysis of the performance of seven WWTPs (CAS + chlorination) in the Kerman Province (Iran) receiving hospital effluents in terms of removal of main conventional parameters and malfunctions | Malfunctions in WWTPs receiving hospital effluents | Conventional parameters: COD, BOD5, DO, TSS, pH, NO2 −, NO3 −, Cl−, and SO4 2− |

| [52] | Investigation carried out in Iran on a pilot-scale system consisting of an integrated anaerobic – aerobic fixed film reactor fed with hospital effluent before co-treatment with urban wastewater | Potential reduction of the organic load in hospital effluents by biological pretreatment before co-treatment | Conventional parameters: COD, BOD5, NH4, turbidity, bacteria, and Escherichia coli |

Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria in HWWs

Although antibiotics have been used in large quantities for some decades, the existence of these substances in the environment has received little attention until recently. In the last few years a more complex investigation of antibiotics has been undertaken in different countries in order to assess their environmental risks. It has been found that the concentrations of antibiotics are higher in hospital effluents than in municipal wastewater, which has higher concentration levels than different surface waters, ground water, and sea water [53]. HWWs could be a source of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria which are excreted by patients. The HWWs either flow into a hospital sewage system or directly into a municipal wastewater sewer, before being subsequently treated in a WWTP. After treatment in a WWTP, the effluent is discharged into surface waters or is used for irrigation. Studies have shown that the release of wastewater from hospitals was associated with an increase in the prevalence of antibiotic resistance. A study conducted in Australia by Thompson et al. 2012 [27] revealed evidence of the survival of antibiotic resistant strains in untreated HWWs and their transit to the STP and then through to the final treated effluent. The strong influence of HWWs on the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant E. coli in Indian WWTPs has been revealed by Alam et al. [24] and Akiba et al. [33]. Untreated hospital and municipal wastewaters were found to be responsible for the dissemination of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria in the rivers of Pakistan [22].

In Bangladesh, a study was conducted by Akter et al. [23] concerning the effects of hospital effluents on the emergence and development of drug-resistant bacteria. They concluded that hospital and agricultural wastewater is mostly responsible for causing environmental pollution by spreading un-metabolized antibiotics and resistant bacteria. Analyses of the results obtained from South Africa indicated that HWWs may be one of the sources of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the receiving WWTP. The findings also revealed that the final effluent discharged into the environment was contaminated with multi-resistant enterococci species, thus posing a health hazard to the receiving aquatic environment as these could eventually be transmitted to the humans and animals exposed to it [43, 54].

As a result, hospitals are important point sources which contribute to the release of both antimicrobials and antibiotic resistant genes into surface waters, especially if hospital wastewaters are discharged into the receiving ambient waters without being treated.

Treatment Sequences for HWWs Under Review

The sequences adopted for the specific treatment of hospital effluent in different countries are reported in Table 3, along with the corresponding bibliographic reference. As can be seen, treatments differ with a trend towards MBR, followed by CAS. Most of the investigations refer to full scale plants and include the following treatment trains: CAS in China, India, Iran, and Vietnam; MBR, MBR + disinfection in China; Flocculation + Activated carbon, Flocculation + CAS in South Korea; Septic Tank + H-SSF bed + V-SSF bed in Nepal, and Ponds in Ethiopia. Seventy-eight percent of the equipped hospitals in Iran used activated sludge systems and 22% used septic tanks [35].

Table 3.

Treatment sequences for hospital effluents included in the chapter

| Country | LAB | PILOT | FULL scale | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China |

MBR MBR + chlorination |

[29] | ||

| China | MBR | [28] | ||

| China | CAS | [10] | ||

| China | Biological contact oxydization + MBR + sodium hypochlorite disinfection | [30] | ||

| Egypt | CAS | [4] | ||

| Ethiopia | Ponds | [32] | ||

| India | CAS + SF + chlorination | [50] | ||

| India | Coagulation + filtration + chlorination | [17] | ||

| India | CAS | [11] | ||

| Indonesia | Aerated fixed film biofilter + O3 | [34] | ||

| Iran | CAS | [36] | ||

| Iran | CAS + chlorination | [51] | ||

| Iran | Fixed film bioreactor + co-treatment | [52] | ||

| Iran | CAS, septic tank | [35] | ||

| Iran | Electrocoagulation | [55] | ||

| Iraq | MBR | [38] | ||

| Nepal | Septic tank + H-SSF bed + V-SSF bed | [40] | ||

| Republic of Korea | Floc + activated carbon, Floc + CAS | [42] | ||

| Taiwan | Preozonation | [49] | ||

| Thailand |

Photo-Fenton Photo-Fenton + CAS |

[45] | ||

| Vietnam | CAS | [6] |

Floc flocculation, SF sand filtration, H-SSF horizontal subsurface flow, V-SSF vertical subsurface flow

Several pilot plants were also tested in different countries: CAS + Sand Filtration + Chlorination in India; Aerated Fixed Film Biofilter + O3 in Indonesia; CAS and Fixed film bioreactor in Iran, and finally preozonation in Taiwan. Lab scales of CAS were tested in Egypt, coagulation + Filtration + Chlorination in India, MBR in Iraq, and Photo-Fenton, Photo-Fenton + CAS in Thailand. Recently, HWWs were also treated by electrocoagulation using aluminum and iron electrodes in Iran [55]. In this study the removal of COD from HWWs was investigated in a lab scale achieving a good removal at pH 3, 30 V, and 60 min reaction time using iron electrodes.

Efficiency of the Adopted HWW Treatment Plants

The removal efficiencies of conventional parameters as well as PhCs from HWWs using different systems are discussed below. As previously reported, different technologies were tested for the treatment of HWWs acting as primary, secondary, and tertiary steps.

Removal Efficiency of Conventional Pollutants

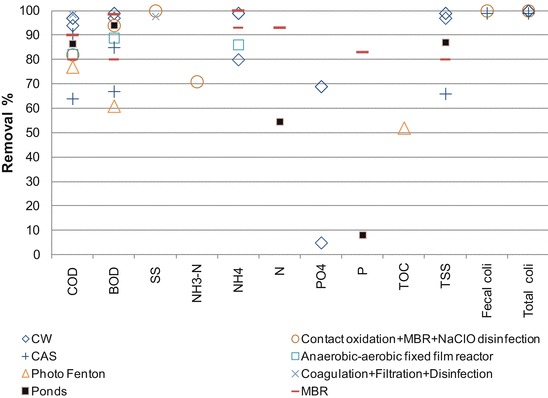

Figure 1 shows the removal efficiency of conventional pollutants obtained from different studies using a primary treatment (Coagulation + filtration + disinfection; Photo Fenton) and secondary treatment (CW; Ponds; CAS; MBR; Biological contact oxidation + MBR + NaClO disinfection; Anaerobic aerobic fixed film reactor, and Aerated fixed film bioreactor + O3).

Fig. 1.

Removal efficiencies from HWW for conventional pollutants in different primary and secondary treatments. Data from [4, 17, 28–30, 32, 35, 38, 45, 52]

Very good removal efficiencies were observed for TSS and BOD5 (97–99%), COD (94–97%), N–NH4 (80–99%), total coliform (99.87–99.999%), E. coli (99.98–99.999%), and Streptococcus (99.3–99.99%) using a septic tank followed by a H-SSF and a V-SSF bed purposely designed for the treatment of HWWs in Nepal [40].

The suitability of a series of facultative and maturation ponds for the treatment of HWWs has been examined in Ethiopia [32]. The percentage treatment efficiency of the pond was 94, 87, 87, 69, 55, 55, and 32 for BOD5, TSS, COD, Nitrate, Nitrite, Total Nitrogen, and Total Dissolved Solids, respectively, while the treatment efficiency for total and fecal coliform bacteria was 99.74% and 99.36%, respectively. However, the effluent still contains large numbers of these bacteria, which are unsuitable for irrigation and aquaculture.

A pilot-scale system integrated anaerobic–aerobic fixed film reactor for HWW treatment was constructed and its performance was evaluated in Iran [52]. The results show that the system efficiently removed 95, 89, and 86% of the COD, BOD, and NH4, respectively. COD removal was greater than 70% when 200 mg/L of ferric chloride was added to an Indian raw hospital effluent and removal increased to over 98% if the coagulant was added to settle HWW. A subsequent disinfection step using calcium hydrochloride reduces not only microorganisms, but also COD [17].

Attempts have been made to reduce toxicity and improve the biodegradability and oxidation degree of pollutants in HWWs prior to discharge into the existing biological treatment plant [45, 56]. Using the photo-Fenton process as a pretreatment method, a significant enhancement of biodegradability was found at the following optimum conditions: a dosage ratio of COD:H2O2:Fe (II) of 1:4:0.1 and a reaction pH of 3. At these conditions, the value of the BOD5:COD ratio increased from 0.30 in raw wastewater to 0.52 for treated wastewater. The toxicity of the wastewater drastically reduced with this process [56].

Nasr and Yazdanbakhsh [35] investigated the treatment efficiency of 70 governmental hospitals from different provinces of Iran, where 78% of them use the CAS system and 22% use septic tanks. The mean removal rates of BOD, COD, and TSS were found to be 67%, 64%, and 66%, respectively. A high removal rate (99–100%) of fecal and total coliforms was obtained using CAS and MBR, followed by disinfection treatment [4, 30].

Figure 1 clearly demonstrates how MBR technology is capable of achieving good removal efficiency (80%) of all the macro-pollutants, with the sole exception of NH3–N, whose removal was found to be 71%.

In Iraq, local wastewater treatment units in various hospitals are not capable of meeting Iraqi standards, especially in terms of nutrient and pathogen removal. For this reason, a lab scale sequencing anoxic/anaerobic membrane bioreactor system is studied to treat hospital wastewater with the aim of removing organic matter, as well as nitrogen and phosphorus under a different internal recycling time mode [38]. The system produces high quality effluents which can meet Iraqi limits for irrigation purposes for all measured parameters.

Membrane separation plays an important role in ensuring excellent and stable effluent quality. The advantages of MBR systems, such as complete solid removal from effluents, effluent disinfection, high loading rate capability, low/zero sludge production, rapid start-up, compact size, and lower energy consumption, have driven authorities to use them in treating HWWs.

An interesting approach to managing hospital effluents has been established in China, where over 50 MBR plants have been successfully built for HWW treatments, with a capacity ranging from 20 to 2,000 m3/d (see Table 4). MBR can effectively save disinfectant consumption (chlorine addition can decrease to 1.0 mg/L), shorten the reaction time (approximately 1.5 min, 2.5–5% of the conventional wastewater treatment process), and deactivate microorganisms. Higher disinfection efficacy is achieved in MBR effluents at lower doses of disinfectant with fewer disinfection by-products (DBPs). Moreover, when the capacity of MBR plants increases from 20 to 1,000 m3/d, their operating costs decrease sharply [29].

Table 4.

Application of MBR in hospital wastewater treatments in China (Adopted from [29])

| Treatment train | Membrane area (m2) | Membrane material | Membrane pore (μm) | Capacity (m3/d) | HRT (h) | Commissioned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBR | 96 | Hollow fiber membrane (PE) | 0.4 | 20 | 2000 | |

| MBR + NaClO3 | 0.2 | 100 | 2004 | |||

| MBR | 140 | 6 | 2004 | |||

| MBR | Organic membrane | 1.3 | 200 | 5 | 2002 | |

| MBR | 200 | 2004 | ||||

| MBR + NaClO | 900 | PVDF | 0.22 | 400 | 7.5 | 2005 |

| MBR + ClO2 | 2,000 | PVDF | 0.22 | 500 | 7 | 2003 |

| MBR + NaClO | 4,000 | Hollow fiber membrane (PVDF) | 0.22 | 1,000 | 5 | 2005 |

| MBR + ClO2 | 8,000 | Hollow fiber membrane (PVDF) | 0.4 | 2,000 | 5.4 | 2008 |

PVDF poly vinyldene fluoride, PE polyethylene

The performance of a submerged hollow fiber membrane bioreactor (MBR) for the treatment of HWW was investigated by [28]. The removal efficiencies for COD, NH4+–N, and turbidity were 80%, 93%, and 83%, respectively, with the average effluent quality of COD <25 mg/L, NH4+–N <1.5 mg/L, and turbidity <3 NTU. Escherichia coli removal was over 98%. The effluent was colorless and odourless.

A combination process of biological contact oxidation, MBR, and sodium hypochlorite disinfectants has been applied to treat HWWs in Tianjin (China). The obtained results showed that the main parameters meet the requirements of the Chinese discharge standards of water pollution for medical organizations [30].

Removal Efficiency of PhCs

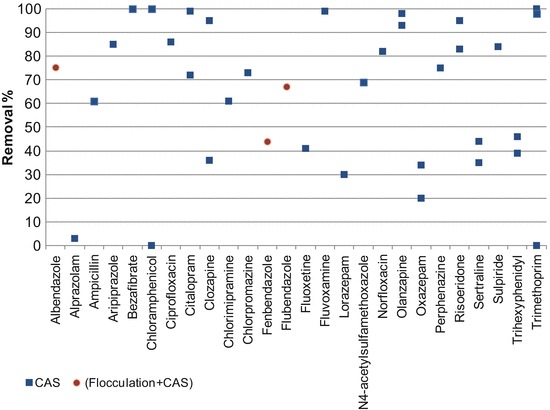

Figure 2 reports all collected data regarding the removal of PhCs in hospital effluents using a full scale CAS system operating in different countries (Vietnam, India, South Korea, and China). High removal efficiencies (>80%) were observed for bezafibrate, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, aripiprazole, clozapine, fluvoxamine, olanzapine, risperidone, sulpiride, and citalopram. Albendazole, ampicillin, N4-acetylsulfamethoxazole, chlorpromazine, chlorimipramine, flubendazole, and perphenazine were moderately removed (60–80%), whereas low removal (less than 50%) was observed for alprazolam, oxazepam, sertraline, trihexyphenidyl, clozapine, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and fenbendazole.

Fig. 2.

Removal efficiencies from HWW for selected PhCs in CAS system. Data from [6, 10, 11, 42]

Negative removals of sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, naproxen, bezafibrate, and ampicillin in sewage treatment plants treating hospital effluents in South India were also observed [11].

The results achieved by Yuan et al. [10] showed that a secondary treatment of a psychiatric hospital was more effective in removing the majority of target compounds [e.g., olanzapine (93–98%), risperidone (72–95%), quetiapine (>73%), and aripiprazole (64–70%)] than treated municipal wastewater.

The overall removal values of ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin in a small HWWTP consisting of a CAS+ anaerobic biological treatment system situated in Vietnam were found to be 86% and 82%, respectively [6].

Regulation

As previously reported, HWWs are often considered similar to urban wastewater. As a result, they are usually co-treated with urban wastewater in the WWTP. Moreover, in many developing countries, they are directly discharged into the environment along with urban wastewater.

There is no regulation in most of the studied countries that imposes authorities to treat HWWs as special waste, with the exception of China where, in July 2005, the Chinese authorities published the “Discharge standard of water pollution for medical organization,” a document outlining comprehensive control requirements for HWWs [30]. Recently, a new law regarding environmental protection has been presented in Vietnam (No. 55/2014/QH13, article 72) [57]. This law obliges hospitals and medical facilities to collect and treat medical wastewater in accordance with environmental standards.

On a global scale, the only existing guidelines concerning hospital effluents management and treatment were published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1999: “Safe Management of Wastes from Health-Care Activities” [58] and updated in 2013 [59]. This publication describes basic methods for the treatment and disposal of health-care wastes and in particular recommends a pretreatment of effluents originated from specific departments as discussed in [60] of this book. These guidelines could be a reference in the management and treatment of HWWs mainly for developing countries in order to preserve the environment.

Conclusions

Hospitals are important point sources contributing to the release of both PhCs and antibiotic resistant bacteria into surface waters, especially if hospital wastewaters are discharged without treatment into the receiving ambient waters. This problem is more severe in developing countries because no wastewater treatment facility is available in most of the cases. Hospital wastewaters are subjected to different treatment scenarios in the studied countries (specific treatment, co-treatment, and direct disposal into the environment). Due to the lack of municipal wastewater treatment plants, the onsite treatment of hospital wastewater before discharge into municipal sewers should be considered a viable option and consequently implemented. Where applicable, the discharge of HWWs into municipal wastewater collection systems is an alternative for wastewater management in hospitals. Upgrading existing WWTPs and improving operation and maintenance practices through the use of experienced operators are recommended measures.

In general, there is no single practice which could be considered a solution to the problem of managing HWWs. Indeed, in many cases, a number of sequences are used in combination. Each practice has its own strengths and weaknesses. More effective disinfection processes coupled with membrane filtration should be adopted for better removal of harmful bacteria and PhCs.

Contributor Information

Paola Verlicchi, Phone: +3939390532974927, Email: paola.verlicchi@unife.it.

Mustafa Al Aukidy, Email: mustafa.alaukidy@gmail.com.

Saeb Al Chalabi, Email: chalabi_sash@yahoo.com.

Paola Verlicchi, Email: paola.verlicchi@unife.it.

References

- 1.Emmanuel E, Perrodin Y, Keck G, Blanchard J-M, Vermande P. Ecotoxicological risk assessment of hospital wastewater: a proposal of framework of raw effluent discharging in urban sewer network. J Hazard Mater. 2005;A117:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verlicchi P, Galletti A, Al Aukidy M. Hospital wastewaters: quali-quantitative characterization and strategies for their treatment and disposal. In: Sharma SK, Sanghi R, editors. Wastewater reuse and management. Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesdaghinia AR, Naddafi K, Nabizadeh R, Saeedi R, Zamanzadeh M. Wastewater characteristics and appropriate methods for wastewater management in the hospitals. Iran J Public Health. 2009;38:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abd El-Gawad HA, Aly AM. Assessment of aquatic environmental for wastewater management quality in the hospitals: a case study. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2011;5(7):474–482. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boillot C, Bazin C, Tissot-Guerraz F, Droguet J, Perraud M, Cetre JC, et al. Daily physicochemical, microbiological and ecotoxicological fluctuations of a hospital effluent according to technical and care activities. Sci Total Environ. 2008;403:113–129. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duong HA, Pham NH, Nguyen HT, Hoang TT, Pham HV, Pham VC, Berg M, Giger W, Alder AC. Occurrence, fate and antibiotic resistance of fluoroquinolone antibacterials in hospital wastewaters in Hanoi, Vietnam. Chemosphere. 2008;72:968–973. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suarez S, Lema JM, Omil F. Pre-treatment of hospital wastewater by coagulation–flocculation and flotation. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:2138–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verlicchi P, Galletti A, Petrović M, Barcelò D. Hospital effluents as a source of emerging pollutants: an overview of micropollutants and sustainable treatment options. J Hydrol. 2010;389:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verlicchi P, Al Aukidy M, Galletti A, Petrovic M, Barceló D. Hospital effluent: investigation of the concentrations and distribution of pharmaceuticals and environmental risk assessment. Sci Total Environ. 2012;430:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan S, Jiang X, Xia X, Zhang H, Zheng S. Detection, occurrence and fate of 22 psychiatric pharmaceuticals in psychiatric hospital and municipal wastewater treatment plants in Beijing, China. Chemosphere. 2013;90:2520–2525. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prabhasankar VP, Joshua DI, Balakrishna K, Siddiqui IF, Taniyasu S, Yamashita N, Kannan K, Akiba M, Praveenkumarreddy Y, Guruge KS. Removal rates of antibiotics in four sewage treatment plants in South India. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Aukidy M, Verlicchi P, Voulvoulis N. A framework for the assessment of the environmental risk posed by pharmaceuticals originating from hospital effluents. Sci Total Environ. 2014;493:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verlicchi P, Galletti A, Masotti L. Management of hospital wastewaters: the case of the effluent of a large hospital situated in a small town. Water Sci Technol. 2010;61:2507–2519. doi: 10.2166/wst.2010.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ort C, Lawrence M, Reungoat J, Eagleham G, Carter S, Keller J. Determination of the fraction of pharmaceutical residues in wastewater originating from a hospital. Water Res. 2010;44:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauwels B, Verstraete W. The treatment of hospital wastewater: an appraisal. J Water Health. 2006;4:405–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kümmerer K, Helmers E. Hospital effluents as a source of gadolinium in the aquatic environment. Environ Sci Technol. 2000;34:573–577. doi: 10.1021/es990633h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gautam AK, Kumar S, Sabumon PC. Preliminary study of physic-chemical treatment options for hospital wastewater. J Environ Manag. 2007;83:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metcalf and Eddy . Wastewater engineering. Treatment and reuse. New York: McGraw Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekhaise FO, Omavwoya BP. Influence of hospital wastewater discharged from University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Benin City on its receiving environment, IDOSI publications. American-Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci. 2008;4(4):484–488. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onesios KM, Yu JT, Bouwer EJ. Biodegradation and removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in treatment systems: a review. Biodegradation. 2009;20:441–466. doi: 10.1007/s10532-008-9237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad M, Khan A, Wahid A, Farhan M, Ali Butt Z, Ahmad F. Role of hospital effluents in the contribution of antibiotics and antibiotics resistant bacteria to the aquatic environment. Pak J Nutr. 2012;11(12):1177–1182. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2012.1177.1182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad M, Khan A, Wahid A, Farhan M, Ali Butt Z, Ahmad F. Urban wastewater as hotspot for antibiotic and antibiotic resistant bacteria spread into the aquatic environment. Asian J Chem. 2014;26(2):579–582. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akter F, Ruhul Amin M, Khan TO, Nural Anwar M, Manjurul Karim M, Anwar Hossain M. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli in hospital wastewater of Bangladesh and prediction of its mechanism of resistance. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;28:827–834. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0875-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam MZ, Aqil F, Ahmad I, Ahmad S. Incidence and transferability of antibiotic resistance in the enteric bacteria isolated from hospital wastewater. Braz J Microbiol. 2013;2013(44):799–806. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822013000300021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verlicchi P, Al Aukidy M, Zambello E. What have we learned from worldwide experiences on the management and treatment of hospital effluent? An overview and a discussion on perspectives. Sci Total Environ. 2015;514:467–491. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messrouk H, Hadj Mahammed M, Touil Y, Amrane A. Physico-chemical characterization of industrial effluents from the town of Ouargla (South East Algeria) Energy Procedia. 2014;50:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2014.06.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson JM, Gundogdu A, Stratton HM, Katouli M. Antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospital waste waters and sewage treatment plants with special reference to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) J Appl Microbiol. 2012;114:44–54. doi: 10.1111/jam.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen X, Ding H, Huang X, Liu R. Treatment of hospital wastewater using a submerged membrane bioreactor. Process Biochem. 2004;39:1427–1431. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00277-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Q, Zhou Y, Chen L, Zheng X. Application of MBR for hospital wastewater treatment in China. Desalination. 2010;250(2):605–608. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, Li Q, Yan S. Design and running for a hospital wastewater treatment project. Adv Mater Res. 2013;777:356–359. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.777.356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mubedi JI, Devarajan N, Faucheur SL, Mputu JK, Atibu EK, Sivalingam P, Prabakar K, Mpiana PT, Wildi W, Poté J. Effects of untreated hospital effluents on the accumulation of toxic metals in sediments of receiving system under tropical conditions: case of South India and Democratic Republic of Congo. Chemosphere. 2013;93(6):1070–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyene H, Redaie G. Assessment of waste stabilization ponds for the treatment of hospital wastewater: the case of Hawassa university referral hospital. World Appl Sci J. 2011;15(1):142–150. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akiba M, Senba H, Otagiri H, Prabhasankar VP, Taniyasu S, Yamashita N, Lee K, Yamamoto T, Tsutsui T, Joshua D, Balakrishna K, Bairy I, Iwata T, Kusumoto M, Kannan K, Guruge SK. Impact of waste water from different sources on the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli in sewage treatment plants in South India. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2015;115:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prayitno, Kusuma Z, Yanuwiadi B, Laksmono RW, Kamahara H, Daimon H. Hospital wastewater treatment using aerated fixed film biofilter – ozonation (Af2b/O3) Adv Environ Biol. 2014;8(5):1251–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nasr MM, Yazdanbakhsh AR. Study on wastewater treatment systems in hospitals of Iran. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2008;5(3):211–215. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azar AM, Jelogir AG, Bidhendi GN, Mehrdadi N, Zaredar N, Poshtegal MK. Investigation of optimal method for hospital wastewater treatment. J Food Agric Environ. 2010;8(2):1199–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eslami A, Amini MM, Yazdanbakhsh AR, Rastkari N, Mohseni-Bandpei A, Nasseri S, Piroti E, Asadi A. Occurrence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Tehran source water, municipal and hospital wastewaters and their ecotoxicological risk assessment. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187:734. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4952-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Hashimia M, Abbas TR, Jasema Y I (2013) Performance of sequencing anoxic/anaerobic membrane bioreactor (SAM) system in hospital wastewater treatment and reuse. Eur Sci J 9(15). ISSN: 1857-7881 (Print); e-ISSN 1857-7431

- 39.Azuma T, Arima N, Tsukada A, Hirami S, Matsuoka R, Moriwake R, Ishiuchi H, Inoyama T, Teranishi Y, Yamaoka M, Mino Y, Hayashi T, Fujita Y, Masada M. Detection of pharmaceuticals and phytochemicals together with their metabolites in hospital effluents in Japan, and their contribution to sewage treatment plant influents. Sci Total Environ. 2016;548–549:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shrestha RR, Haberl R, Laber J. Constructed wetland technology transfer to Nepal. Water Sci Technol. 2001;43:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashfaqa M, Khan KN, Rasool S, Mustafa G, Saif-Ur-Rehman M, Nazar MF, Sun Q, Yu C. Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of fluoroquinolone antibiotics in hospital waste of Lahore, Pakistan. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;42:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sim WJ, Kim HY, Choi SD, Kwon JH, Oh JE. Evaluation of pharmaceuticals and personal care products with emphasis on anthelmintics in human sanitary waste, sewage, hospital wastewater, livestock wastewater and receiving water. J Hazard Mater. 2013;248–249:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iweriebor BC, Gaqavu S, Obi LC, Nwodo UU, Okoh AI. Antibiotic susceptibilities of Enterococcus species isolated from hospital and domestic wastewater effluents in lice, Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:4231–4246. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120404231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin AY, Wang XH, Lin CF. Impact of wastewaters and hospital effluents on the occurrence of controlled substances in surface waters. Chemosphere. 2010;81:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kajitvichyanukul P, Suntronvipart N. Evaluation of biodegradability and oxidation degree of hospital wastewater using photo-Fenton process as the pretreatment method. J Hazard Mater. 2006;B138:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stephenson T, Judd S, Jefferson B, Brindle K. Membrane bioreactors for wastewater treatment. Alliance House, London: IWA Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu KD, Xiong GL, Zhan MS, Zhang SB, Tan GF. Investigation on the current hospital wastewater treatment in Wuhan. China Water Wastewater. 2005;21:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sozzi E, Fabre K, Fesselet J-F, Ebdon JE, Taylor H. Minimizing the risk of disease transmission in emergency settings: novel in situ physico-chemical disinfection of pathogen-laden hospital wastewaters. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(6):e0003776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chiang CF, Tsai CT, Lin ST, Huo CP, Lo KW. Disinfection of hospital wastewater by continuous ozonation. J Environ Sci Health A. 2003;A38(12):2895–2908. doi: 10.1081/ESE-120025839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chitnis V, Chitnis S, Vaidya K, Ravikant S, Patil S, Chitnis DS. Bacterial population changes in hospital effluent treatment plant in Central India. Water Res. 2004;38:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahvi A, Rajabizadeh A, Fatehizadeh A, Yousefi N, Hosseini H, Ahmadian M. Survey wastewater treatment condition and effluent quality of Kerman Province hospitals. World Appl Sci J. 2009;7(12):1521–1525. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rezaee A, Ansari M, Khavanin A, Sabzali A, Aryan MM. Hospital wastewater treatment using an integrated anaerobic aerobic fixed film bioreactor. Am J Environ Sci. 2005;1(4):259–263. doi: 10.3844/ajessp.2005.259.263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kummerer K. Drugs in the environment: emission of drugs, diagnostic aids and disinfectant into wastewater by hospital in relation to other sources – a review. Chemosphere. 2001;45:957–969. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lupo A, Coyne S, Berendonk TU. Origin and evolution of antibiotic resistance: the common mechanisms of emergence and spread in water bodies. Front Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dehghani M, Seresht SS, Hashemi H. Treatment of hospital wastewater by electrocoagulation using aluminum and iron electrodes. Int J Environ Health Eng. 2014;3:15. doi: 10.4103/2277-9183.132687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kajitvichyanukul P, Lu MC, Liao CH, Wirojanagud W, Koottatep T. Degradation and detoxification of formalin wastewater by advanced oxidation processes. J Hazard Mater. 2006;135:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Law No. 55/2014/QH13 dated June 23, 2014 of the National Assembly on Environmental Protection. http://www.ilo.org/dyn/legosh/en/f?p=LEGPOL:503:9521088818065:::503:P503_REFERENCE_ID:172932. Accessed 17 Feb 2017

- 58.Prüss A, Giroult E, Rushbrook P, editors. Safe management of wastes from health-care activities. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chartier Y, et al., editors. Safe management of wastes from health-care activities. 2. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carraro E, Bonetta S, Bonetta S. Hospital wastewater: existing regulations and current trends in management. Handb Environ Chem. 2017 [Google Scholar]