Abstract

Background

It is unclear whether blood pressure (BP) should be altered actively during the acute phase of stroke.

Objectives

To assess the effect of lowering or elevating BP in people with acute stroke, and the effect of different vasoactive drugs on BP in acute stroke.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched June 2009), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 4, 2009), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2009), EMBASE (1980 to October 2009), and Science Citation Index (1981 to October 2009).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of interventions that would be expected, on pharmacological grounds, to alter BP in patients within one week of the onset of acute stroke.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently applied the trial inclusion criteria, assessed trial quality, and extracted data.

Main results

We identified 131 trials involving in excess of 18,000 patients; a further 13 trials are ongoing. We obtained data for 43 trials (7649 patients). Among BP‐lowering trials, beta receptor antagonists lowered BP (early systolic BP (SBP) mean difference (MD) ‐6.1 mmHg, 95% CI ‐11.4 to ‐0.9; late SBP MD ‐4.9 mmHg, 95% CI ‐10.2 to 0.4; late diastolic BP (DBP) MD ‐4.5 mmHg, 95% CI ‐7.8 to ‐1.2). Oral calcium channel blockers (CCB) lowered BP (late SBP MD ‐3.2 mmHg, 95% CI ‐5.4 to ‐1.1; early DBP MD ‐2.5, 95% CI ‐5.6 to 0.7; late DBP MD ‐2.1, 95% CI ‐3.5 to ‐0.7). Nitric oxide donors lowered BP (early SBP MD ‐10.3 mmHg, 95% CI ‐17.6 to ‐3.0). Prostacyclin lowered BP (late SBP MD, ‐7.7 mmHg, 95% CI ‐15.6 to 0.2; late DBP MD ‐3.9 mmHg, 95% CI ‐8.1 to 0.4). Among BP‐increasing trials, diaspirin cross‐linked haemoglobin (DCLHb) increased BP (early SBP MD 15.3 mmHg, 95% CI 4.0 to 26.6; late SBP MD 15.9 mmHg, 95% CI 1.8 to 30.0). None of the drug classes significantly altered outcome apart from DCLHb which increased combined death or dependency (odds ratio (OR) 5.41, 95% CI 1.87 to 15.64).

Authors' conclusions

There is not enough evidence to evaluate reliably the effect of altering BP on outcome after acute stroke. However, treatment with DCLHb was associated with poor clinical outcomes. Beta receptor antagonists, CCBs, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin each lowered BP during the acute phase of stroke. In contrast, DCLHb increased BP.

Plain language summary

Vasoactive drugs for acute stroke

In patients who have just had a stroke (a sudden catastrophe in the brain either because an artery to the brain blocks, or because an artery in or on the brain ruptures and bleeds) very high and very low blood pressure may be harmful. Drugs which raise low blood pressure or lower high blood pressure might benefit acute stroke patients. This review of 43 trials involving 7649 participants found that there was not enough evidence to decide if drugs which can alter blood pressure should or should not be used in patients with acute stroke. More research is needed.

Background

Description of the condition

Stroke is the third most common cause of death and the commonest cause of disability in the western world. Acute stroke, whether due to infarction or haemorrhage, is associated with high blood pressure in 75% of patients of whom 50% have a previous history of high blood pressure (International Society of Hypertension 2003). The mechanisms underlying hypertension in stroke are complex but pre‐existing hypertension (present in 50% to 60% of patients), hospitalisation stress, activation of the neuro‐endocrine pathways, and the Cushing reflex, each contribute (International Society of Hypertension 2003; Sprigg 2005). Low blood pressure is not common in acute stroke but it, like high blood pressure, is associated with a poor outcome (Castillo 2004; Leonardi‐Bee 2002; Vemmos 2004). Possible reasons for low blood pressure include potentially reversible conditions such as hypovolaemia, sepsis, impaired cardiac output secondary to cardiac failure, arrhythmias or cardiac ischaemia, and aortic dissection (Sprigg 2005).

Description of the intervention

Although debated more than 20 years ago, it still remains unclear whether hypertension should (Spence 1985) or should not (Yatsu 1985) be treated acutely following stroke. Recent guidelines recommend that acute lowering of blood pressure should be delayed for several days or even weeks unless blood pressure is higher than 220/120 mmHg, higher than 200/100 mmHg with end organ involvement (hypertensive encephalopathy, aortic dissection, cardiac ischaemia, pulmonary oedema, acute renal failure), or higher than 200/120 mmHg with primary intracerebral haemorrhage (PICH) (AHA‐HS 2007; AHA‐IS 2007; ESO 2008). Though the evidence is weak (class 1, level of evidence B) guidelines now recommend that patients who have elevated blood pressure and are otherwise eligible for treatment of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) may have their blood pressure lowered so that systolic blood pressure (SBP) is ≤ 185 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is ≤ 110 mmHg before thrombolysis using intravenous labetalol, nitropaste or nicardipine and it should be maintained below 180/105 mmHg for at least the first 24 hours after therapy (AHA‐IS 2007; ESO 2008). Similarly, guidelines recommend that causes of low blood pressure in the setting of acute stroke should be sought with a view to correcting reversible causes such as hypovolaemia and cardiac arrhythmias (AHA‐IS 2007; ESO 2008).

How the intervention might work

A number of small studies have assessed the relationship between blood pressure and outcome. A meta‐analysis of these and other studies found that elevated blood pressure was associated with a poor outcome (Willmot 2004). Data from 17,398 patients in the International Stroke Trial (IST) identified a U‐shaped relationship such that both low and high blood pressure was associated independently with increased early death and later death or dependency (Leonardi‐Bee 2002). A high blood pressure is also associated with increased early recurrence (Leonardi‐Bee 2002; Sprigg 2006). In ischaemic stroke, hypertension also appears to affect adversely through increasing the risk of cerebral oedema, but not haemorrhagic transformation (Leonardi‐Bee 2002) as shown in the IST analysis. Haematoma expansion is related to high blood pressure in patients with PICH although this relationship may be confounded by stroke severity and time to presentation (Bath 2003). Since cerebral autoregulation is lost following stroke (Burke 1986; Paulson 1990; Strandgaard 1973) such that cerebral blood flow becomes dependent on systemic blood pressure, some researchers have hypothesised that blood pressure should be increased (Sandercock 1992) after stroke to improve perfusion to the penumbral region, and several case series and small trials have been published. In a recent meta‐regression of blood pressure in acute stroke involving data from randomised controlled trials, large increases or reductions in blood pressure were associated with harm whereas moderate reductions were associated with a non‐significant reduction in death or dependency (Geeganage 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions that would be expected, on pharmacological grounds, to alter blood pressure in patients within one week of the onset of acute ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke. A related review restricted inclusion to those trials which specifically studied the effect of changing blood pressure in acute stroke (BASC I). The aim of this review is to assess the effect of lowering or elevating blood pressure in people with acute stroke, and the effect of different vasoactive drugs on blood pressure in acute stroke.

Objectives

To determine whether lowering or elevating blood pressure in patients with acute stroke is safe and effective in reducing the risk of early and late death and functional dependency.

To determine the effect of vasoactive drugs on blood pressure patients with acute stroke.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published and unpublished randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials (i.e. trials that used a non‐random method of treatment allocation, for example hospital number, date of birth or day of the week), of vasoactive drugs in acute ischaemic stroke or acute primary intracerebral haemorrhage where drug therapy was initiated within one week of stroke onset. We excluded uncontrolled studies, confounded controlled studies where the intervention was compared with another active therapy, and studies of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Types of participants

Adults (aged 18 years and over) of either sex with acute ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke (within one week of onset) who were eligible for randomisation to either active treatment or placebo/open control.

Types of interventions

All randomised controlled acute stroke trials where vasoactive drugs were used in the acute treatment of stroke.

Types of outcome measures

Early (within one month) and end‐of‐trial mortality; early death or deterioration; end‐of‐trial mortality or dependency; blood pressure and heart rate at baseline, and during early (less than 24 hours) and late (24 to 72 hours) treatment; length of hospital stay and discharge destination. We defined disability or dependency as a Barthel Index 0 to 55 or Rankin score 3 to 5. We also noted the presence of 'hypotension' (however defined by trialists) where given.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module.

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register, which was last searched by the Managing Editor in June 2009 using a search strategy designed to identify all relevant trials. In addition, we searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 4, 2009), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2009) (Appendix 1), EMBASE (1980 to October 2009) (Appendix 2), and Science Citation Index (ISI Web of Science, 1981 to October 2009) (Appendix 3). We did not apply any language restrictions.

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing trials:

we searched reviews of hypertension in acute stroke from the CDSR and existing Cochrane and other stroke overviews relating to drugs which may alter blood pressure, including: calcium channel blockers (CCBs) (Horn 2001), nitric oxide (Bath 2002), pentoxifylline (Bath 2004/2), amphetamine (Martinsson 2007; Sprigg 2007), tirilazad (Tirilazad International Steering Committee 2001), naftidrofuryl (Leonardi‐Bee 2007), vinpocetine (Bereczki 2008) and prostacyclin (Bath 2004/1) as well as other generic reviews (Geeganage 2009);

we searched the Ongoing Trials section of Stroke and the Internet Stroke Center Stroke Trials Registry (Stroke Center) (October 2009);

we scanned the reference lists of relevant trials and existing review articles;

we contacted research workers in this field (see Acknowledgements);

we contacted the following pharmaceutical companies: Bayer (nimodipine), Napp (pentoxifylline), Novartis (isradipine), Lipha Sante (naftidrofuryl), Hoffmann la Roche (N Methyl D Aspartate), Hoechst (flunarizine) and UCB Pharma (piracetam) in 1999 for the previous version of the review.

Data collection and analysis

We identified and independently assessed published and unpublished trials and decided whether to include or exclude them. One review author (CG) identified data in published material and sought additional information from the principal investigators of the trials where necessary. We resolved disagreements by discussion. Where available, we re‐analysed individual patient data and used the resulting group data in preference to published data. We recorded information on the methods of randomisation, concealment of allocation, blinding, analysis (intention‐to‐treat or efficacy analysis), stroke type (ischaemia or haemorrhage), drug dose, route of administration (oral, transdermal or intravenous) and timing, blood pressure and heart rate (before and during treatment), numbers of deaths, functional disability, quality of life, length of stay, and adverse effects such as hypotension,

We assessed the methodological quality of trials, especially relating to concealment of allocation as detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We calculated the weighted estimate of the typical treatment effect across trials (odds ratio (OR) for binary data, mean difference (MD) for continuous data) using aggregated patient data in Review Manager 5.0 (RevMan 2008); this software also tests for heterogeneity between the trials.

Results

Description of studies

Where a trial used more than one dose of a particular drug then the reference is written as author followed by date followed by dose of drug. When referencing the whole trial the references for all the doses will be used (e.g. Saxena 1999 50 mg/Saxena 1999 100 mg). Blood pressure (BP) data were available in 43 trials including 7649 patients (Characteristics of included studies). We excluded more than 80 studies as the relevant data were unobtainable, either because they were not present in trial reports and could not be provided by trialists, or because they had been discarded or they could not be released until publication of the final trial reports (Characteristics of excluded studies).

The trials involved 16 combinations of drug classes and routes of administration: oral or sublingual angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (perindopril, captopril and lisinopril); oral angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARA) (candesartan); oral beta receptor antagonists (βRA) (atenolol, propanolol); combined alpha and beta receptor antagonists (labetalol); oral thiazide diuretics (bendrofluazide), intravenous CCBs (flunarizine, isradipine, nimodipine); oral CCBs (nimodipine, nicardipine); intravenous DCLHb (a haemoglobin analogue); intravenous magnesium sulphate; intravenous naftidrofuryl; transdermal glyceryl trinitrate (a nitric oxide donor); intravenous piracetam; combined intravenous prostacyclin; intravenous glucose potassium insulin (GKI); intravenous insulin; intravenous phenylephrine; and intravenous and or oral mixed antihypertensive therapy (Characteristics of included studies).

Patients were recruited into trials within six to 168 hours from stroke onset; most were enrolled within 24 to 168 hours (Characteristics of included studies). Nine studies included patients who were hypertensive at the time of recruitment (Characteristics of included studies); the other studies involved patients with a range of BPs. Two trials studied phenylephrine and DCLHb which elevate BP (Saxena 1999 25 mg/Saxena 1999 50 mg/Saxena 1999 100 mg; Hillis 2003). Thirty‐eight trials were published and five trials unpublished (IMAGES Pilot; Lowe 1993; Pokrupa 1986; Strand 1984; Uzuner 1995/180 mg). Routes of administration included oral, intravenous (iv), transdermal, sublingual or combinations of these (Characteristics of included studies). The treatment duration varied from 24 hours to nine months (Characteristics of included studies). Some drugs were given in two phases, initially intravenously then orally (CCB, magnesium sulphate, naftidrofuryl, piracetam) (Characteristics of included studies). Combinations of intravenous and oral antihypertensive drugs were used to lower BP in the intensive as well as guideline group of INTERACT pilot trial (INTERACT pilot 2008). Three trials used transdermal glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) 5 mg daily for 12 days (Bath 2000); GTN 5 mg, 5/10 mg, 10 mg (Rashid 2003 5 mg/Rashid 2003 5/10 mg/Rashid 2003 10 mg) for 10 days; GTN 5 mg (Willmot 2006) for seven days. There was one dose escalation study of 8 mmol, 12 mmol, 16 mmol of magnesium sulphate over 24 hours (Muir 1995).

Risk of bias in included studies

The methods used in the 43 trials are summarised in the Characteristics of included studies table. All trials were double‐blind, with the exceptions of one single‐blinded (Saxena 1999 100 mg/Saxena 1999 25 mg/Saxena 1999 50 mg), four outcome‐blinded (Gray 2007; INTERACT pilot 2008; Rashid 2003 10 mg/Rashid 2003 5 mg/Rashid 2003 5/10 mg; Willmot 2006) and two open studies (Barer 1988 atenolol/Barer 1988 propanolol; Walters 2006). The method of randomisation was only given for 22 trials (Ahmed 2000 1 mg/Ahmed 2000 2 mg; Barer 1988 atenolol/Barer 1988 propanolol; Bath 2000; Bogousslavsky 1990; Dyker 1997; Eames 2005; Eveson 2007; Gray 2007; IMAGES Pilot; INTERACT pilot 2008; Kaste 1994/120 mg; Lees 1995; Limburg 1990; Lowe 1993; PASS 1995; Pokrupa 1986; Potter 2009 labetalol/Potter 2009 lisinopril; Rashid 2003 5 mg/Rashid 2003 5/10 mg/Rashid 2003 10 mg; Strand 1984; Walters 2006; Willmot 2006; Wimalarat 1994/120mg/Wimalarat 1994/240mg). All trials were analysed by the intention‐to‐treat analysis with the exception of two (Huczynski 1988; Martinez‐Vila 1990).

There were 23 single‐centred trials. All trials used computerised tomography (CT) to exclude patients with PICH with the exception of nine trials that included both types of stroke (Ahmed 2000 1 mg/Ahmed 2000 2 mg; Barer 1988 atenolol/Barer 1988 propanolol; Barer 1988/50 mg/Barer 1988/80 mg; Fagan 1988/120 mg/Fagan 1988/240 mg; Gray 2007; Potter 2009 labetalol/Potter 2009 lisinopril; Rashid 2003 5 mg/Rashid 2003 5/10 mg/Rashid 2003 10 mg; VENUS 1995; Willmot 2006). One trial only included patients with acute spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) diagnosed by CT (INTERACT pilot 2008). For the lisinopril study randomisation was done before neuroimaging and those with non‐ischaemic stoke were subsequently withdrawn from the study (Eveson 2007).

Effects of interventions

General

We identified a total of 131 trials involving in excess of 18,000 patients. However, data were only available for 43 trials involving 7649 patients. We excluded 86 trials as BP or outcome data were not available. The patients receiving placebo or control treatment in eight trials (Ahmed 2000 1 mg/Ahmed 2000 2 mg; Barer 1988 atenolol/Barer 1988 propanolol; Barer 1988/50 mg/Barer 1988/80 mg; Fagan 1988/120 mg/Fagan 1988/240 mg; Rashid 2003 5 mg/Rashid 2003 5/10 mg/Rashid 2003 10 mg; Saxena 1999 25 mg/Saxena 1999 50 mg/Saxena 1999 100 mg; Wimalarat 1994/120mg/Wimalarat 1994/240mg; Potter 2009 labetalol/Potter 2009 lisinopril) acted as controls for more than one group of actively treated patients; control participants in these studies were divided equally between each active treatment group to ensure that the total number of control participants was correct. This strategy is recommended by the Cochrane Stroke Group and avoids artificially inflating patient numbers and therefore narrowing confidence intervals.

Blood pressure

Baseline SBP was mismatched between the treatment and control groups across all treatments (MD ‐1.6 mmHg, 95% CI ‐2.8 to ‐0.4) and especially for intravenous CCBs (MD ‐6.6 mmHg, 95% CI ‐13.4 to 0.2) (Appendix 4). Several drug classes lowered BP, including: beta receptor antagonists (early SBP, MD ‐6.1 mmHg, 95% CI ‐11.4 to ‐0.9; late SBP MD ‐4.9 mmHg, 95% CI ‐10.2 to 0.4; late DBP MD ‐4.5 mmHg, 95% CI ‐7.8 to ‐1.2); oral CCBs (late SBP MD ‐3.2 mmHg, 95% CI ‐5.4 to ‐1.1; early DBP MD ‐2.5, 95% CI ‐5.6 to 0.7; late DBP MD ‐2.1, 95% CI ‐3.5 to ‐0.7); nitric oxide donors (early SBP MD ‐10.3 mmHg, 95% CI ‐17.6 to ‐3.0), and prostacyclin (late SBP MD ‐7.7 mmHg, 95% CI ‐15.6 to 0.2; late DBP MD ‐3.9 mmHg, 95% CI ‐8.1 to 0.4).

BP lowering is also seen for several other antihypertensive agents although the small number of participants studied meant that differences in BP were not always statistically significant. Drugs showing hypotensive properties included: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists, bendrofluazide, intravenous CCBs and GKI. Neither magnesium, naftidrofuryl nor piracetam had appreciable effects on BP. INTERACT pilot 2008 lowered SBP (early MD ‐14.0 mmHg 95% CI ‐17.2 to ‐10.8, late MD ‐11.0 mmHg, 95% CI ‐14.0 to ‐8.0) in the intensive treatment versus guideline treatment arm.

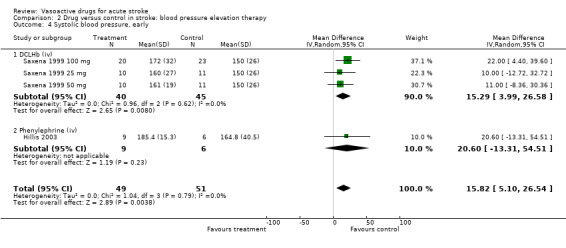

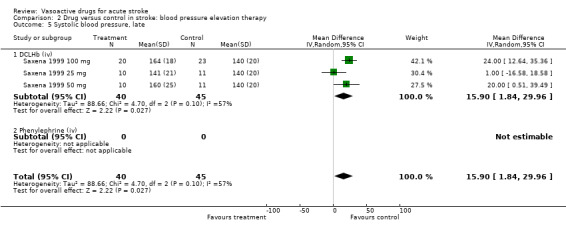

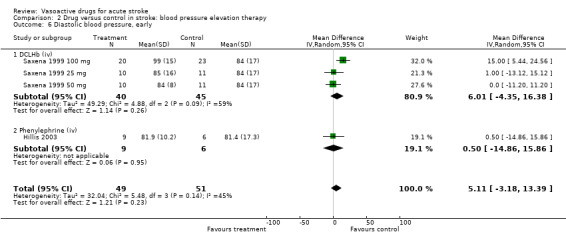

In contrast, DCLHb increased BP (early SBP MD 15.3 mmHg, 95% CI 4.0 to 26.6; late SBP MD 15.9 mmHg, 95% CI 1.8 to 30.0). Intravenous phenylephrine also showed a trend towards an increase in SBP (MD 20.6, 95% CI ‐13.3 to 54.5) as compared to control.

Heart rate

Heart rate was lowered by beta blockers (early heart rate (HR) MD ‐6.8 beats/minute, 95% CI ‐9.6 to ‐4.0; late HR MD ‐9.3 beats/minute, 95% CI ‐12.0 to ‐6.6); and oral CCBs (late HR MD ‐2.8 beats/minute, 95% CI ‐3.9 to ‐1.7); and increased by nitric oxide donors (MD 6.3 beats/minute 95% CI 2.9 to 9.7). Intravenous CCBs, ACE inhibitors, naftidrofuryl, magnesium, and DCLHb did not alter heart rate.

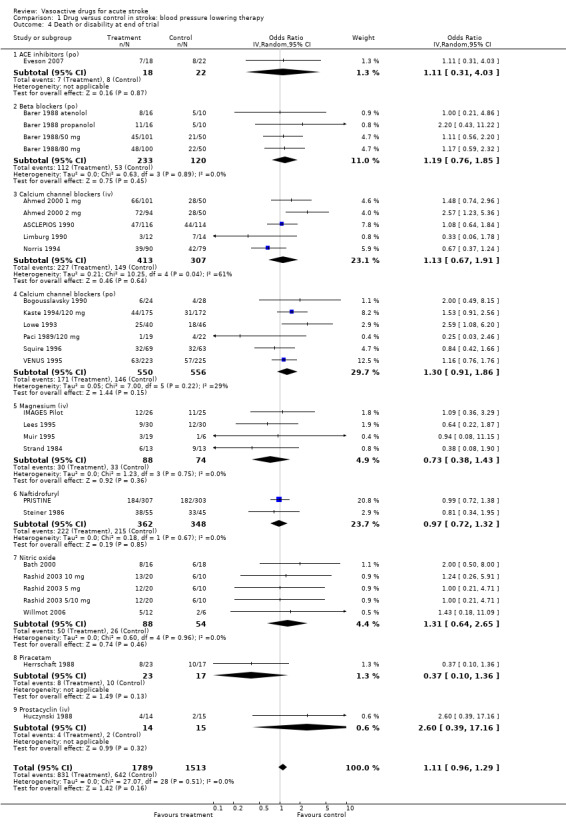

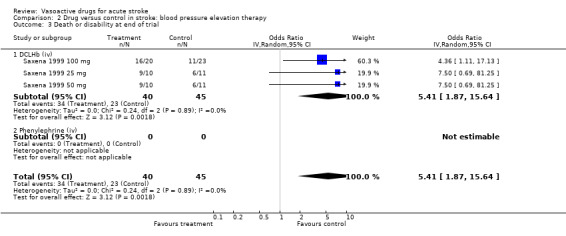

Death or dependency

There was no evidence of an effect on death for any agent except DCLHb which significantly increased the odds of death or dependency (OR 5.41, 95% CI 1.87 to 15.64). A trend for an increase in combined end of trial death or disability was observed for oral CCBs (odds ratio (OR) 1.30, 95% CI 0.91 to1.86).

Hypotensive events

There was no significant difference for oral CCBs (total events four active, six control, OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.74) and mixed antihypertensive therapy (total events five active, six control, OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.33 to 4.7) in the number of hypotensive events. None of the other agents reported hypotensive events in trial publications.

Relationship between blood pressure and outcome

The numbers of trials and participants with data on BP and outcome were not identical and it was not possible to relate group differences in BP with group differences in outcome. This problem was compounded by biologically important differences in baseline BP between treated and control groups.

Discussion

Beta receptor antagonists, oral calcium channel blockers (CCBs), glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), prostacyclin and mixed antihypertensive therapy lowered blood pressure (BP) during the first three days of treatment. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, bendroflumethiazide, intravenous CCBs, insulin and GKI also appeared to lower BP as compared to the controls. In contrast, magnesium, naftidrofuryl, and piracetam had no effect on BP. Nevertheless, these observations may be partly confounded by mismatches in baseline BP (significantly so for intravenous CCBs). Baseline imbalances in BP would have profound effects on outcome and therefore change the BP‐outcome relationship. A definitive assessment as to whether these drugs change BP will be dependent on analysis of individual patient data from these trials. Unfortunately, individual patient data were not available for most of the included trials; the presence of these data would have addressed this issue. Further, the apparent BP‐reducing effect of GKI may be due to the confounding in the GIST trial, in which the controls were treated with intravenous saline, and the treatment group received intravenous dextrose, so the BP difference may not be attributable to the GKI lowering BP, but to the control group having less hypovolaemia/hypotension because of the saline (Gray 2007).

None of the drug classes altered outcome apart from diaspirin cross‐linked haemoglobin (DCLHb) which significantly increased combined death and dependency compared with control. There was no significant difference in outcome for CCBs, beta blockers, ACE‐I, magnesium, and nitric oxide. The relationship between BP and outcome could not be studied for methodological reasons in the present review. However, the relationship between BP and outcome based on many of the included trials has been assessed in a meta‐regression (Geeganage 2009). The results revealed a U‐shaped relationship between BP changes and outcome, with the lowest risk of death or combined death or dependency at the end of follow up in patients with BP reductions ranging from eight to 15 mmHg. Although large falls or increases in BP were associated with a higher risk of poor outcomes, a modest reduction may reduce death and combined death or dependency, although confidence intervals were wide and compatible with an overall benefit or hazard.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Trials of vasoactive drugs in acute stroke reveal that beta receptor antagonists, oral calcium channel blockers (CCBs), glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), prostacyclin and mixed antihypertensive therapy each lower blood pressure (BP). In contrast, diaspirin cross‐linked haemoglobin (DCLHb) and phenylephrine increases BP. However, these data do not allow the effect of changing BP on outcome to be assessed. In the absence of definitive information, there is no clear indication for the deliberate alteration of BP during the first few days after stroke.

Implications for research.

The existing completed studies of vasoactive drugs in acute stroke are all small or medium sized (fewer than 1000 participants) and, hence, likely to be underpowered. One or more large trials (several thousand participants) are now required to determine whether altering (raising or lowering) BP can be safe and efficacious; such studies are ongoing (ENOS 2006; INTERACT 2 2007; SCAST 2005).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2009 | New search has been performed | This review was updated in October 2009 and includes the following: (1) the addition of 11 completed trials involving 2281 patients; (2) the addition of 13 ongoing or planned trials. The previous version of the review included 32 trials involving 5368 patients. The conclusions of this review have not changed with the addition of the new data. |

| 1 October 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Change of authors. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2000 Review first published: Issue 4, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 21 February 2007 | Amended | Substantive amendment. |

Acknowledgements

The Blood pressure in Acute Stroke Collaboration (BASC) comprises the following people.

Data collation and analysis, and review writing for this version of the review: Chamila Geeganage, Philip Bath (previous version: Fiona J Bath and R Iddenden)

Trialists: Ahmed N (Sweden), Asplund K (Sweden), Autret A (France), Barer D (UK), Bath PMW (UK), Bereczki D (Hungary), Bogousslavsky J (Switzerland), Chan YW (Hong Kong), Davis S (Australia), de Deyn PP (Belgium), Donnan G (Australia), Dyker AG (UK), Eveson D (UK), Fogelholm R (Finland), Gelmers HJ (Netherlands), Gray CS (UK), Grotta J (USA), Hachinski V (Canada), Hakim RP (Canada), Heiss WH (Germany), Herrschaft H (Germany), Hillis AB (USA), Horn J (Netherlands), Hsu CY (USA), Huczynski J (Poland), Kaste M (Finland), Koudstall PJ (Netherlands), Kramer G (Switzerland), Lees KR (UK), Limberg M (Netherlands), Lisk R (Cameroon), Lowe G (UK), Muir KW (UK), Mistri A (UK), Murphy JJ (UK), Orgogozo JM (France), Pokrupa RP (Canada), Rashid P (UK), Saxena R (Netherlands), Steiner T (UK), Strand T (Sweden), Uzuner N (Turkey), Wahlgren N (Sweden), Walters MR (UK), Willmot M (UK), Wimalaratna HSK (UK), Wong WJ (Taiwan).

Companies (for the previous version of this review): Bayer (Canada), Lipha Sante (France), UCB pharma (Belgium).

We are grateful to the Cochrane Stroke Group Editorial Board and external peer reviewers for their comments on this review. All the analyses and their interpretation reflect the opinions of BASC; no pharmaceutical company was involved in the analysis or interpretation of data, or in the writing of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

01. stroke.mp. 02. infarction.mp. 03. exp brain Infarction/ 04. exp infarction, anterior cerebral artery/ 05. exp infarction, middle cerebral artery/ 06. exp infarction, posterior cerebral artery/ 07. exp brain ischemia/ 08. brain ischaemia.mp. 09. cerebral ischaemia.mp. 10. hemorrhage.mp. 11. exp cerebral hemorrhage/ 12. cerebral haemorrhage.mp. 13. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. (nitrate or L‐arginine or thiazide or diuretics or beta blockers or calcium channel blockers or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists or rennin inhibitors or neuroprotective agents or alpha receptor antagonists or vasoconstrictors or adrenoceptor agonists or centrally acting antihyperten$ or vasodilators or hemodilution or haemodilution).mp. 15. (bendrofluazide or bendroflumethiazide or hydrochrlothiazide or atenolol or propanalol or bisoprolol or labetalol or nimodipine or nicardipine or amilodipine or felodipine or clinidipine or isradipine or nifedipine or nisolodipine or tirilazad or flunarazine or captopril or enalapril or lisinopril or perindopril or ramipril or candesartan or losartan or telmisartan or valsartan or clonidine or pentoxifylline or pentifylline or naftidrofuryl or prostacyclin or PGI2 or magnesium or papaverine or vinpocetin or piracetam or dopamine or dobutamine or adrenaline or noradrenaline or phenylephrine or amphetamine or caffeinol or caffeine or theophylline or diaspirin cross linked haemoglobin or DCLHb).mp. 16. 14 or 15 17. 13 and 16 18. (randomized controlled trial.pt. or controlled clinical trial.pt.or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or clinical trials as topic.sh. or randomly.ab. or trial.ti.) and humans.sh. 19. 17 and 18

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

01. stroke.mp. 02. infarction.mp. 03. exp brain Infarction/ 04. exp brain infarction size/ 05. brain stem infarction 06. cerebellum infarction 07. brain ischemia.mp. 08. brain ischaemia.mp. 09. exp brain ischemia/ 10. cerebral ischaemia.mp. 11. hemorrhage.mp. 12. exp cerebral hemorrhage/ 13. cerebral haemorrhage.mp. 14. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 15. (nitrate or L‐arginine or thiazide or diuretics or beta blockers or calcium channel blockers or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists or rennin inhibitors or neuroprotective agents or alpha receptor antagonists or vasoconstrictors or adrenoceptor agonists or centrally acting antihyperten$ or vasodilators or hemodilution or haemodilution).mp. 16. (bendrofluazide or bendroflumethiazide or hydrochrlothiazide or atenolol or propanalol or bisoprolol or labetalol or nimodipine or nicardipine or amilodipine or felodipine or clinidipine or isradipine or nifedipine or nisolodipine or tirilazad or flunarazine or captopril or enalapril or lisinopril or perindopril or ramipril or candesartan or losartan or telmisartan or valsartan or clonidine or pentoxifylline or pentifylline or naftidrofuryl or prostacyclin or PGI2 or magnesium or papaverine or vinpocetin or piracetam or dopamine or dobutamine or adrenaline or noradrenaline or phenylephrine or amphetamine or caffeinol or caffeine or theophylline or diaspirin cross linked haemoglobin or DCLHb).mp. 17. 15 or 16 18. 14 and 17 19. ((RANDOMIZED‐CONTROLLED‐TRIAL/ or RANDOMIZATION/ or CONTROLLED‐STUDY/ or MULTICENTER‐STUDY/ or PHASE‐3‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL/ or PHASE‐4‐CLINICAL‐TRIAL/ or DOUBLE‐BLIND‐PROCEDURE/ or SINGLE‐BLIND‐PROCEDURE/) or ((RANDOM* or CROSS?OVER* or FACTORIAL* or PLACEBO* or VOLUNTEER*) or ((SINGL* or DOUBL* or TREBL* or TRIPL*) adj3 (BLIND* or MASK*))).ti,ab) and human*.ec,hw,fs. 20. 18 and 19

Appendix 3. Science Citation Index search strategy

01. stroke.TS./TI 02. acute stroke.TS./TI. 03. cerebral infarction.TS./TI. 04. brain Infarction.TS./TI. 05. brain ischemia.TS./TI. 06. brain ischaemia.TS./TI. 07. brain ischemia.TS./TI. 08. cerebral ischaemia.TS./TI. 09. cerebral hemorrhage.TS./TI. 10. cerebral haemorrhage.TS./TI. 11. cerebral bleeding.TS./TI. 12. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 13. (nitrate or L‐arginine or thiazide or diuretics or beta blockers or calcium channel blockers or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists or rennin inhibitors or neuroprotective agents or alpha receptor antagonists or vasoconstrictors or adrenoceptor agonists or centrally acting antihyperten$ or vasodilators or hemodilution or haemodilution.TS./TI. 14. (bendrofluazide or bendroflumethiazide or hydrochrlothiazide or atenolol or propanalol or bisoprolol or labetalol or nimodipine or nicardipine or amilodipine or felodipine or clinidipine or isradipine or nifedipine or nisolodipine or tirilazad or flunarazine or captopril or enalapril or lisinopril or perindopril or ramipril or candesartan or losartan or telmisartan or valsartan or clonidine or pentoxifylline or pentifylline or naftidrofuryl or prostacyclin or PGI2 or magnesium or papaverine or vinpocetin or piracetam or dopamine or dobutamine or adrenaline or noradrenaline or phenylephrine or amphetamine or caffeinol or caffeine or theophylline or diaspirin cross linked haemoglobin or DCLHb).TS./TI. 15. 13 or 14 16. 12 and 15 17. (randomized controlled trial.TI. or controlled clinical trial.TI.or randomized.TI. or placebo.TI. or clinical trials TI. or randomly.TI. or trial.TI.) and humans.TI. 18. 16 and 17

Appendix 4. Baseline haemodynamic measures for included studies

| Drug class | Baseline SBP | N | Baseline DBP | N | Baseline HR | N |

| MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | MD (95% CI) | ||||

| BP lowering therapy | ||||||

| ACE inhibitors (po) | 1.79 (‐3.84 to 7.43) | 4 | ‐0.22 (‐4.34 to 3.89) | 4 | 0.22 (‐5.31 to 5.75) | 3 |

| ARA (po) | ‐2.00 (‐6.32 to 2.32) | 1 | 0.00 (‐2.97 to 2.97) | 1 | ||

| Beta blockers (po) | 0.34 (‐4.27 to 4.96) | 5 | 0.03 (‐3.75 to 3.80) | 5 | ‐0.36 (‐3.73 to 3.02) | 4 |

| Calcium channel blockers (iv) | ‐6.60 (‐13.37 to 0.16) | 6 | ‐1.72 (‐5.99 to 2.55) | 6 | ‐0.24 (‐3.18 to 2.71) | 4 |

| Calcium channel blockers (po) | 0.44 (‐2.82 to 1.94) | 14 | ‐0.11 (‐1.54 to 1.33) | 14 | ‐1.32 (‐2.77 to 0.13) | 9 |

| Glucose potassium insulin (iv) | ‐2.5 (‐6.29 to 1.29) | 1 | ||||

| Insulin (iv) | ‐7.00 (‐20.73 to 6.73) | 1 | 0.00 (‐9.08 to 9.08) | 1 | ||

| Magnesium (iv) | 1.42 (‐7.13 to 9.98) | 4 | 0.99 (‐4.37 to 6.35) | 4 | ‐1.79 (‐7.95 to 4.37) | 4 |

| Naftidrofuryl | ‐1.46 (‐7.95 to 5.02) | 2 | ‐0.18 (‐4.70 to 4.35) | 2 | 1.27(‐4.30 to 6.83) | 2 |

| Nitric oxide | 0.98 (‐6.13 to 8.08) | 5 | 3.9 (‐0.22 to 8.03) | 5 | 3.44 (‐2.29 to 9.17) | 5 |

| Other vasodilators (po) | ‐24.83 (‐48.89 to ‐0.77) | 1 | 8.33 (‐1.66 to 18.32) | 1 | ||

| Piracetam | ‐2.11 (‐6.39 to 2.16) | 2 | ‐0.39 (‐2.34 to 1.56) | 2 | ||

| Prostacyclin | ‐2.75 (‐10.87 to 5.36) | 3 | ‐4.84 (‐9.72 to 0.04) | 3 | ‐0.71 (‐5.52 to 4.11) | 3 |

| Thiazide diuretics (po) | ‐20.00(‐39.44 to ‐0.56) | 1 | ‐15.00 (‐29.51 to ‐0.49) | 1 | ||

| Unclassified or combined | ‐2.00 (‐5.61 to 1.61) | 1 | ‐4.00 (‐6.83 to ‐1.17) | 1 | ||

| Total | ‐1.59 (‐2.83 to ‐0.35) | 51 | ‐0.41 (‐1.37 to 0.55) | 50 | ||

| BP elevation therapy | ||||||

| DCLHb | 5.37 (‐3.59 to 14.34) | 3 | ‐2.56 (‐8.78 to 3.65) | 3 | 3.37 (‐2.43 to 9.17) | 3 |

| Phenylephrine | ‐27.5 (‐50.83 to ‐4.17) | 1 | ‐8.30 (‐19.13 to 2.53) | 1 | ||

| Total | ‐1.53 (‐15.15 to 12.09) | 4 | ‐3.73 (‐8.99 to 1.54) | 4 | 3.37 (‐2.43 to 9.17) | 3 |

Significant results are in bold type

CI: confidence interval DBP: diastolic blood pressure DCLHb: diaspirin cross‐linked haemoglobin HR: heart rate iv: intravenous MD: mean difference N: number of studies po: oral SBP: systolic blood pressure

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

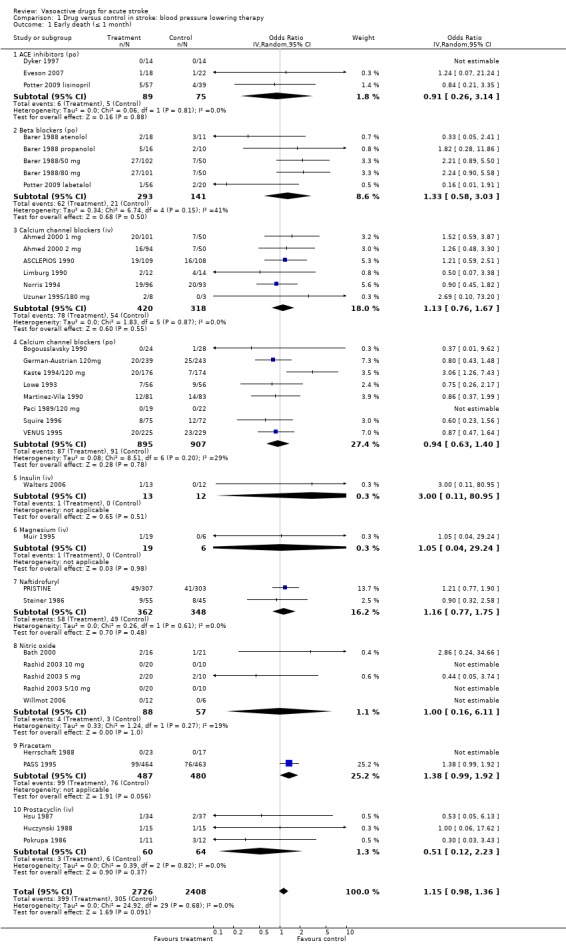

| 1 Early death (≤ 1 month) | 36 | 5134 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.98, 1.36] |

| 1.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 3 | 164 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.26, 3.14] |

| 1.2 Beta blockers (po) | 5 | 434 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.58, 3.03] |

| 1.3 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 6 | 738 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.76, 1.67] |

| 1.4 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 8 | 1802 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.63, 1.40] |

| 1.5 Insulin (iv) | 1 | 25 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.00 [0.11, 80.95] |

| 1.6 Magnesium (iv) | 1 | 25 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.04, 29.24] |

| 1.7 Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 710 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.77, 1.75] |

| 1.8 Nitric oxide | 5 | 145 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.16, 6.11] |

| 1.9 Piracetam | 2 | 967 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.99, 1.92] |

| 1.10 Prostacyclin (iv) | 3 | 124 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.12, 2.23] |

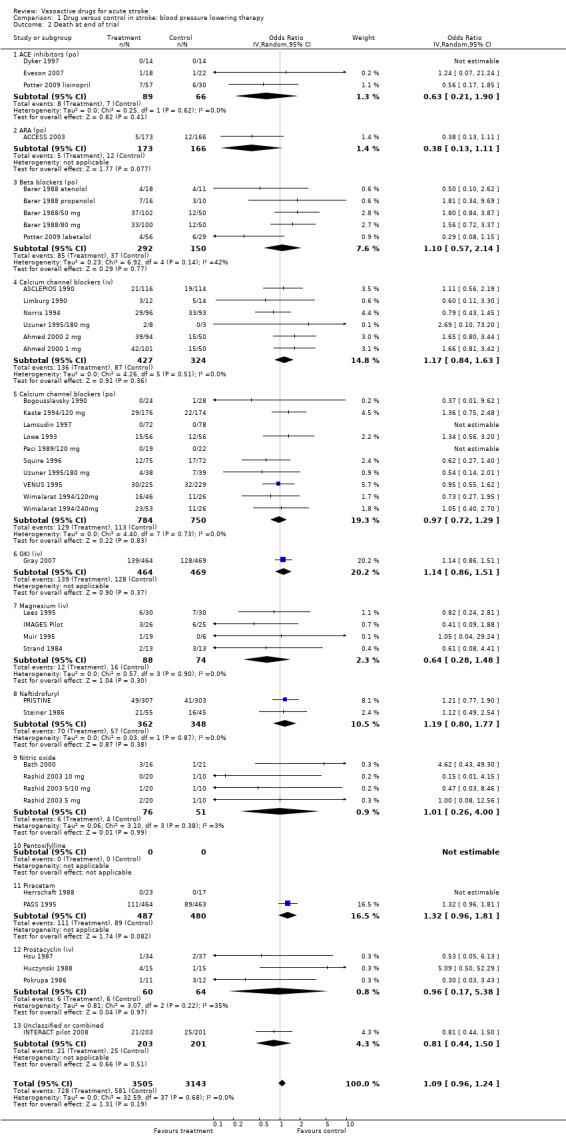

| 2 Death at end of trial | 41 | 6648 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.96, 1.24] |

| 2.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 3 | 155 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.21, 1.90] |

| 2.2 ARA (po) | 1 | 339 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.13, 1.11] |

| 2.3 Beta blockers (po) | 5 | 442 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.57, 2.14] |

| 2.4 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 6 | 751 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.84, 1.63] |

| 2.5 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 10 | 1534 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.72, 1.29] |

| 2.6 GKI (iv) | 1 | 933 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.86, 1.51] |

| 2.7 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 162 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.28, 1.48] |

| 2.8 Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 710 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.80, 1.77] |

| 2.9 Nitric oxide | 4 | 127 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.26, 4.00] |

| 2.10 Pentoxifylline | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.11 Piracetam | 2 | 967 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.96, 1.81] |

| 2.12 Prostacyclin (iv) | 3 | 124 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.17, 5.38] |

| 2.13 Unclassified or combined | 1 | 404 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.44, 1.50] |

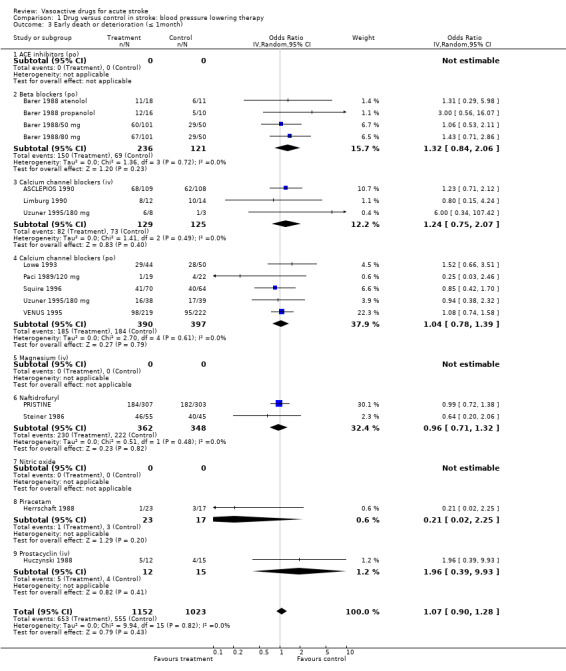

| 3 Early death or deterioration (≤ 1month) | 15 | 2175 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.90, 1.28] |

| 3.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.2 Beta blockers (po) | 4 | 357 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.84, 2.06] |

| 3.3 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 3 | 254 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.75, 2.07] |

| 3.4 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 5 | 787 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.78, 1.39] |

| 3.5 Magnesium (iv) | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.6 Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 710 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.71, 1.32] |

| 3.7 Nitric oxide | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.8 Piracetam | 1 | 40 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.02, 2.25] |

| 3.9 Prostacyclin (iv) | 1 | 27 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.96 [0.39, 9.93] |

| 4 Death or disability at end of trial | 29 | 3302 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.96, 1.29] |

| 4.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 1 | 40 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.31, 4.03] |

| 4.2 Beta blockers (po) | 4 | 353 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.76, 1.85] |

| 4.3 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 5 | 720 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.67, 1.91] |

| 4.4 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 6 | 1106 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.91, 1.86] |

| 4.5 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 162 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.38, 1.43] |

| 4.6 Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 710 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.72, 1.32] |

| 4.7 Nitric oxide | 5 | 142 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.64, 2.65] |

| 4.8 Piracetam | 1 | 40 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.10, 1.36] |

| 4.9 Prostacyclin (iv) | 1 | 29 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.60 [0.39, 17.16] |

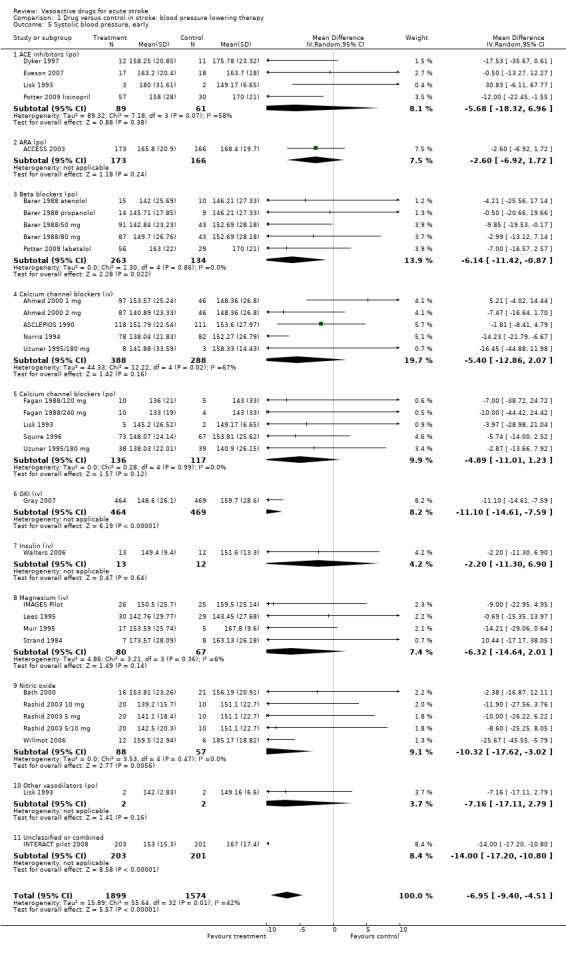

| 5 Systolic blood pressure, early | 30 | 3473 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.95 [‐9.40, ‐4.51] |

| 5.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 4 | 150 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.68 [‐18.32, 6.96] |

| 5.2 ARA (po) | 1 | 339 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.60 [‐6.92, 1.72] |

| 5.3 Beta blockers (po) | 5 | 397 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.14 [‐11.42, ‐0.87] |

| 5.4 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 5 | 676 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.40 [‐12.86, 2.07] |

| 5.5 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 5 | 253 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.89 [‐11.01, 1.23] |

| 5.6 GKI (iv) | 1 | 933 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐11.10 [‐14.61, ‐7.59] |

| 5.7 Insulin (iv) | 1 | 25 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.20 [‐11.30, 6.90] |

| 5.8 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 147 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.32 [‐14.64, 2.01] |

| 5.9 Nitric oxide | 5 | 145 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.32 [‐17.62, ‐3.02] |

| 5.10 Other vasodilators (po) | 1 | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.16 [‐17.11, 2.79] |

| 5.11 Unclassified or combined | 1 | 404 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐14.0 [‐17.20, ‐10.80] |

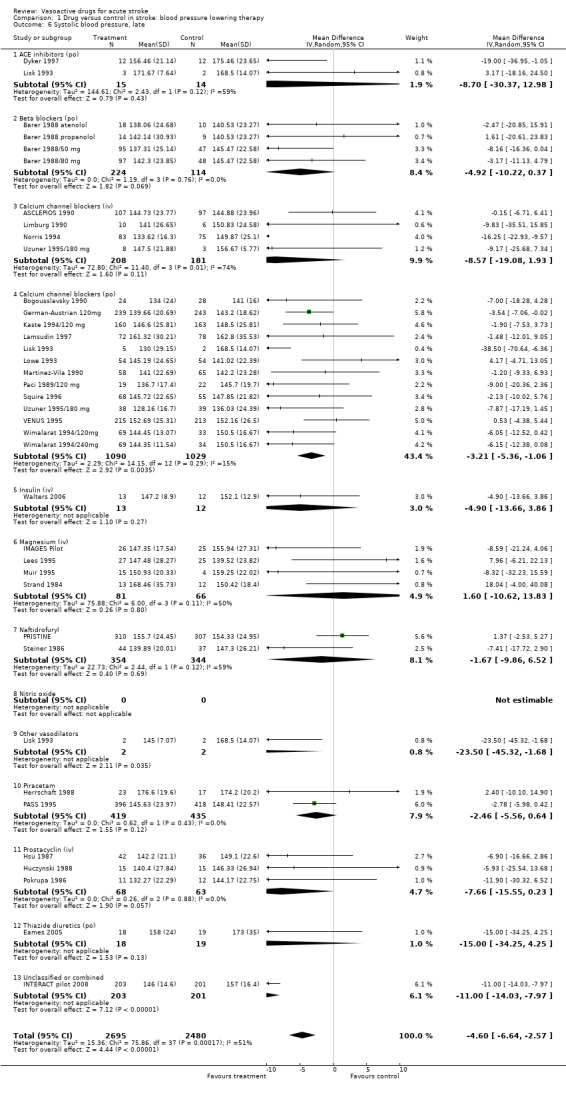

| 6 Systolic blood pressure, late | 35 | 5175 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.60 [‐6.64, ‐2.57] |

| 6.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 2 | 29 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.70 [‐30.37, 12.98] |

| 6.2 Beta blockers (po) | 4 | 338 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.92 [‐10.22, 0.37] |

| 6.3 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 4 | 389 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐8.57 [‐19.08, 1.93] |

| 6.4 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 13 | 2119 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.21 [‐5.36, ‐1.06] |

| 6.5 Insulin (iv) | 1 | 25 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.90 [‐13.66, 3.86] |

| 6.6 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 147 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.60 [‐10.62, 13.83] |

| 6.7 Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 698 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.67 [‐9.86, 6.52] |

| 6.8 Nitric oxide | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.9 Other vasodilators | 1 | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐23.5 [‐45.32, ‐1.68] |

| 6.10 Piracetam | 2 | 854 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.46 [‐5.56, 0.64] |

| 6.11 Prostacyclin (iv) | 3 | 131 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.66 [‐15.55, 0.23] |

| 6.12 Thiazide diuretics (po) | 1 | 37 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐15.0 [‐34.25, 4.25] |

| 6.13 Unclassified or combined | 1 | 404 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.00 [‐14.03, ‐7.97] |

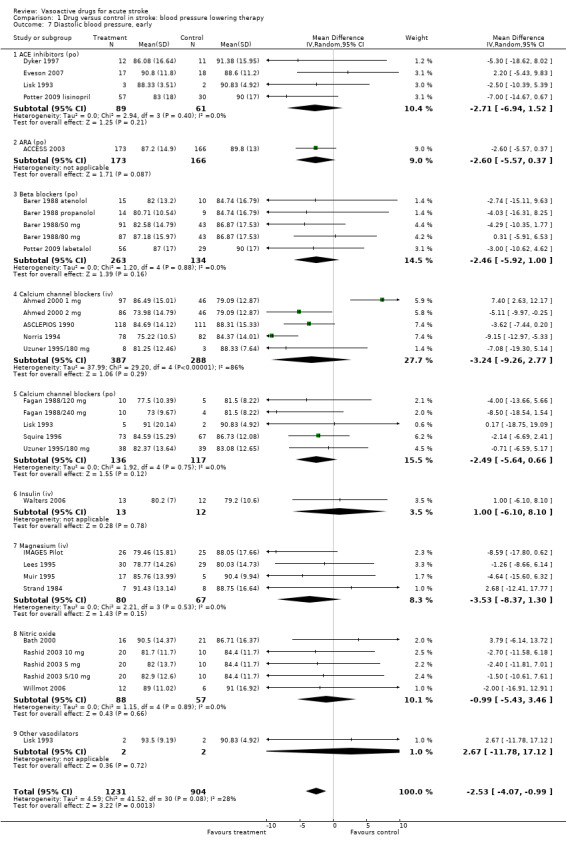

| 7 Diastolic blood pressure, early | 28 | 2135 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.53 [‐4.07, ‐0.99] |

| 7.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 4 | 150 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.71 [‐6.94, 1.52] |

| 7.2 ARA (po) | 1 | 339 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.60 [‐5.57, 0.37] |

| 7.3 Beta blockers (po) | 5 | 397 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.46 [‐5.92, 1.00] |

| 7.4 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 5 | 675 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.24 [‐9.26, 2.77] |

| 7.5 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 5 | 253 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.49 [‐5.64, 0.66] |

| 7.6 Insulin (iv) | 1 | 25 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [‐6.10, 8.10] |

| 7.7 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 147 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.53 [‐8.37, 1.30] |

| 7.8 Nitric oxide | 5 | 145 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.99 [‐5.43, 3.46] |

| 7.9 Other vasodilators | 1 | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.67 [‐11.78, 17.12] |

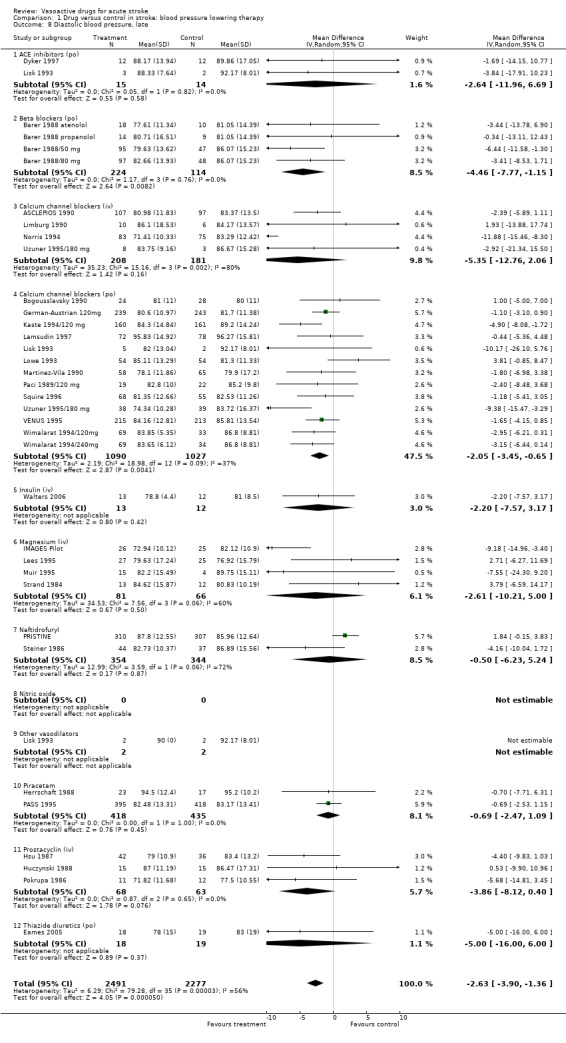

| 8 Diastolic blood pressure, late | 34 | 4768 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.63 [‐3.90, ‐1.36] |

| 8.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 2 | 29 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.64 [‐11.96, 6.69] |

| 8.2 Beta blockers (po) | 4 | 338 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.46 [‐7.77, ‐1.15] |

| 8.3 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 4 | 389 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.35 [‐12.76, 2.06] |

| 8.4 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 13 | 2117 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.05 [‐3.45, ‐0.65] |

| 8.5 Insulin (iv) | 1 | 25 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.20 [‐7.57, 3.17] |

| 8.6 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 147 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.61 [‐10.21, 5.00] |

| 8.7 Naftidrofuryl | 2 | 698 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.50 [‐6.23, 5.24] |

| 8.8 Nitric oxide | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.9 Other vasodilators | 1 | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.10 Piracetam | 2 | 853 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.69 [‐2.47, 1.09] |

| 8.11 Prostacyclin (iv) | 3 | 131 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.86 [‐8.12, 0.40] |

| 8.12 Thiazide diuretics (po) | 1 | 37 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.0 [‐16.00, 6.00] |

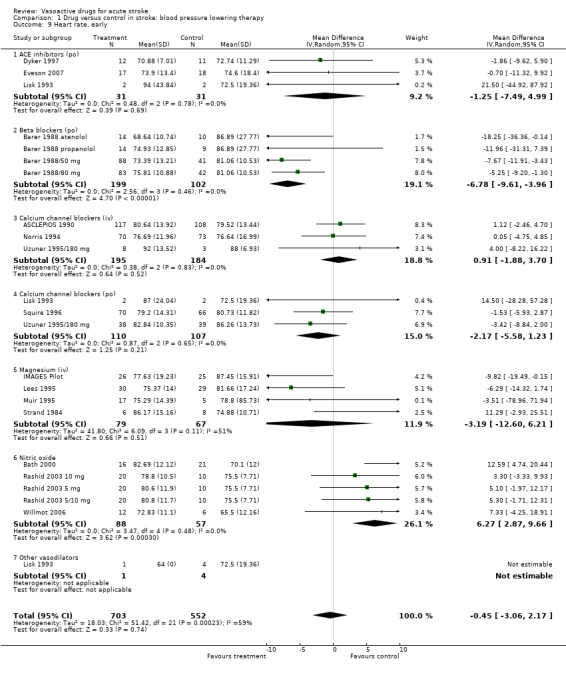

| 9 Heart rate, early | 20 | 1255 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.45 [‐3.06, 2.17] |

| 9.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 3 | 62 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.25 [‐7.49, 4.99] |

| 9.2 Beta blockers (po) | 4 | 301 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.78 [‐9.61, ‐3.96] |

| 9.3 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 3 | 379 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [‐1.88, 3.70] |

| 9.4 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 3 | 217 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.17 [‐5.58, 1.23] |

| 9.5 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 146 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.19 [‐12.60, 6.21] |

| 9.6 Nitric oxide | 5 | 145 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 6.27 [2.87, 9.66] |

| 9.7 Other vasodilators | 1 | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

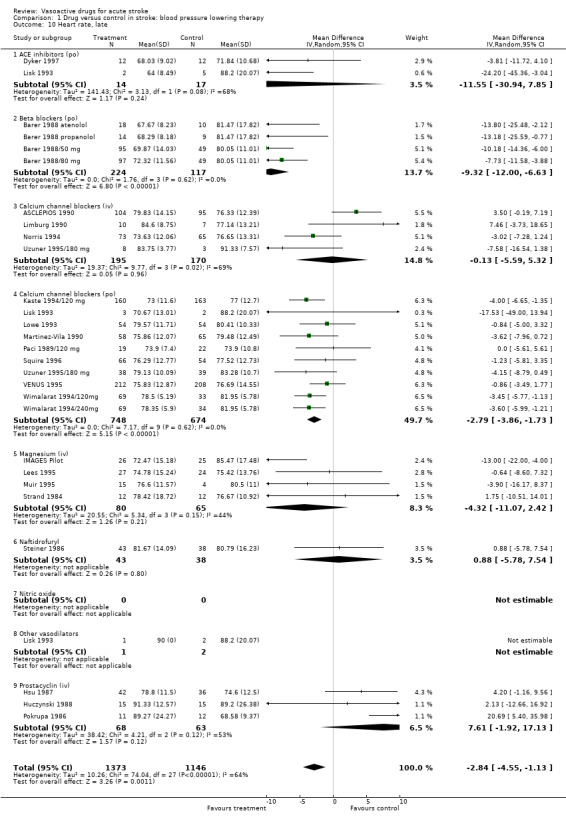

| 10 Heart rate, late | 26 | 2519 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.84 [‐4.55, ‐1.13] |

| 10.1 ACE inhibitors (po) | 2 | 31 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐11.55 [‐30.94, 7.85] |

| 10.2 Beta blockers (po) | 4 | 341 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.32 [‐12.00, ‐6.63] |

| 10.3 Calcium channel blockers (iv) | 4 | 365 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.13 [‐5.59, 5.32] |

| 10.4 Calcium channel blockers (po) | 10 | 1422 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.79 [‐3.86, ‐1.73] |

| 10.5 Magnesium (iv) | 4 | 145 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.32 [‐11.07, 2.42] |

| 10.6 Naftidrofuryl | 1 | 81 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [‐5.78, 7.54] |

| 10.7 Nitric oxide | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.8 Other vasodilators | 1 | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.9 Prostacyclin (iv) | 3 | 131 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 7.61 [‐1.92, 17.13] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 1 Early death (≤ 1 month).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 2 Death at end of trial.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 3 Early death or deterioration (≤ 1month).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 4 Death or disability at end of trial.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 5 Systolic blood pressure, early.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 6 Systolic blood pressure, late.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 7 Diastolic blood pressure, early.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 8 Diastolic blood pressure, late.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 9 Heart rate, early.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure lowering therapy, Outcome 10 Heart rate, late.

Comparison 2. Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

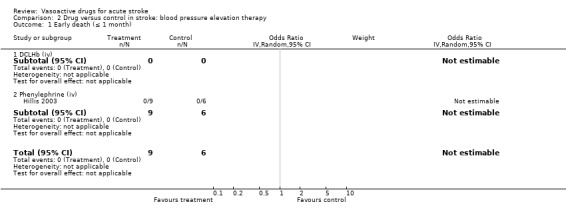

| 1 Early death (≤ 1 month) | 1 | 15 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.1 DCLHb (iv) | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 1 | 15 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

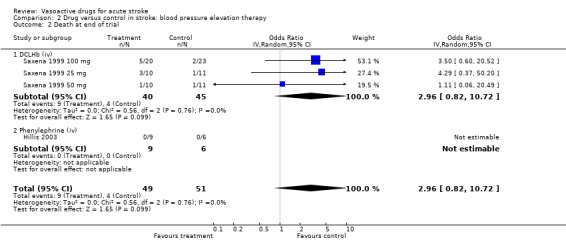

| 2 Death at end of trial | 4 | 100 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.96 [0.82, 10.72] |

| 2.1 DCLHb (iv) | 3 | 85 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.96 [0.82, 10.72] |

| 2.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 1 | 15 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Death or disability at end of trial | 3 | 85 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 5.41 [1.87, 15.64] |

| 3.1 DCLHb (iv) | 3 | 85 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 5.41 [1.87, 15.64] |

| 3.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Systolic blood pressure, early | 4 | 100 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 15.82 [5.10, 26.54] |

| 4.1 DCLHb (iv) | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 15.29 [3.99, 26.58] |

| 4.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 1 | 15 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 20.60 [‐13.31, 54.51] |

| 5 Systolic blood pressure, late | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 15.90 [1.84, 29.96] |

| 5.1 DCLHb (iv) | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 15.90 [1.84, 29.96] |

| 5.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Diastolic blood pressure, early | 4 | 100 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 5.11 [‐3.18, 13.39] |

| 6.1 DCLHb (iv) | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 6.01 [‐4.35, 16.38] |

| 6.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 1 | 15 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [‐14.86, 15.86] |

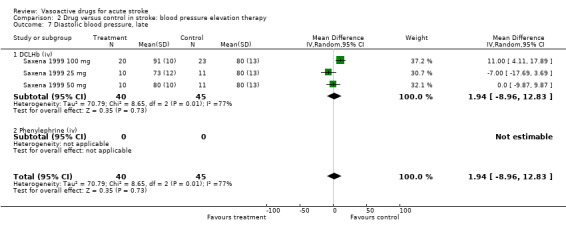

| 7 Diastolic blood pressure, late | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.94 [‐8.96, 12.83] |

| 7.1 DCLHb (iv) | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.94 [‐8.96, 12.83] |

| 7.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

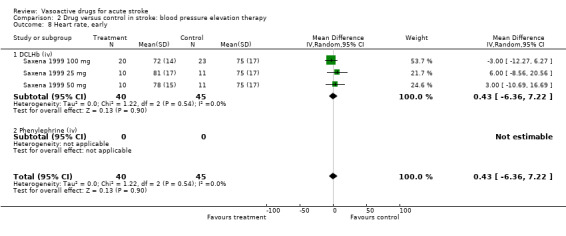

| 8 Heart rate, early | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [‐6.36, 7.22] |

| 8.1 DCLHb (iv) | 3 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [‐6.36, 7.22] |

| 8.2 Phenylephrine (iv) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 1 Early death (≤ 1 month).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 2 Death at end of trial.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 3 Death or disability at end of trial.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 4 Systolic blood pressure, early.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 5 Systolic blood pressure, late.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 6 Diastolic blood pressure, early.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 7 Diastolic blood pressure, late.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug versus control in stroke: blood pressure elevation therapy, Outcome 8 Heart rate, early.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

ACCESS 2003.

| Methods | Multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Method of randomisation not known | |

| Participants | Germany 339 patients ‐ T: 173, C:166 Age: T: 68.3 years; C: 67.8 years Male: T: 50%; C: 52% Inclusion: IS 100% CT Enrolment within 24 to 36 hours after admission | |

| Interventions | T: candesartan 4 mg po on day 1 and dose was increased to 8 or 16 mg if BP exceeded 160 mmHg systolic or 100 mmHg diastolic C: matching placebo Rx: 7 days | |

| Outcomes | BP was measured by a nurse or automatically Case fatality and disability using BI 3 months after the end of placebo‐controlled 7‐day period | |

| Notes | Exclusion: age > 85 years, > 70% stenosis of internal carotid artery, disorders in consciousness, cardiac failure, unstable angina, malignant hypertension, and high grade aortic or mitral stenosis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

Ahmed 2000 1 mg.

| Methods | As for Ahmed 2000 2 mg | |

| Participants | — | |

| Interventions | — | |

| Outcomes | — | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | According to predetermined randomisation lists |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | Probably not done 101 patients did not complete 21 days of treatment This includes 2 trial withdrawals |

Ahmed 2000 2 mg.

| Methods | Multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Randomisation by predetermined randomisation list | |

| Participants | Sweden 295 patients: T1: 101, T2: 94, C: 100 Age: T1: 71.9 years , T2: 72.1 years, C: 71 years Male: T1: 45, T2: 45, C: 45 Inclusion: clinical diagnosis of ischaemic stroke in the carotid artery territory Enrolment: within 24 hours of ictus | |

| Interventions | T1: nimodipine iv 1 mg/hour for 5 days followed by oral nimodipine 30 mg qid for 16 days T2: nimodipine iv 2 mg/hour for 5 days followed by po nimodipine 30 mg qid for 16 days C: matching placebo | |

| Outcomes | Transformed Orgogozo score and transformed Barthel index score on the follow up at day 21 | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | According to predetermined randomisation lists |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | Probably not done 101 patients did not complete 21 days of treatment This includes 2 trial withdrawals |

ASCLEPIOS 1990.

| Methods | Multicentre (40), double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Method of randomisation unknown ITT analysis | |

| Participants | European and Canadian 234 patients ‐ T:120, C:114 Age: 45 to 85 years Males: T: 76, C: 69 Patients with ischaemic MCA stroke presenting with hemiparesis or hemiplegia within 12 hours of onset 100% CT and/or MRI within 72 hours 1 patient > 12 hours (15 hours) and one patient < 45 years (44 years) | |

| Interventions | T: isradipine as continuous iv infusion (80 ug/hour) for 72 hours then po (2.5 mg bd) C: matching iv/po placebo Rx: for 28 days | |

| Outcomes | Assessments at baseline and days 1, 3, 7, 14, 28, 90 Neurological score (modified by Orgogozo et al (1993)); Barthel Index (extended to include death as worst possible outcome) Missing data: day 28: T: 11, C: 6; day 90: T: 4, C: 0 Blood pressure measured at baseline and days 1, 2, 3 (method of measurement unknown) | |

| Notes | Ex: Massive hemispheric damage; very mild stroke (neurological score > 65); any condition where previous neurological deficits might hinder ability to detect improvement from current stroke; other systemic diseases such as gastrointestinal system, liver, kidneys; acute or unstable cardiovascular disease, except AF; exposure to drugs that may interfere with safety or efficacy; pregnancy, lactation Data provided by J‐M Orgogozo (principal investigator) TIAs will be excluded and analysed separately | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

Barer 1988 atenolol.

| Methods | Multicentre, open randomised controlled Separate randomisation schemes for each hospital ITT analysis | |

| Participants | UK 55 patients: T1: 18, T2:16, C:21 Mean age: T1: 73 years, T2: 72 years, C: 70 years Males: T1:12, T2:8, C:8 Inclusion: clinically diagnosed hemispheric strokes Patients should be conscious and able to swallow tablets Enrolment within 48 hours | |

| Interventions | T1: atenolol po 50 mg daily T2: propranolol 80 mg po daily Rx: 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Same time points used as Barer 1988 | |

| Notes | Same exclusions as Barer 1988 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randomisation was done in block of 3 with separate schemes for each hospital |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | High risk | Open randomised controlled trial |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

Barer 1988 propanolol.

| Methods | As for Barer 1988 atenolol | |

| Participants | — | |

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | — | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | High risk | Open randomised controlled |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | 38 patients lost to follow up |

Barer 1988/50 mg.

| Methods | Single centre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Method of randomisation not known 38 patients lost to FU PP analysis | |

| Participants | UK 303 patients: T1:102, T2:101, C:100 Mean age: T1: 70.6 years, T2: 68.2 years, C: 69 years Males: T1: 53, T2: 57, C:49 Inclusion: clinically diagnosed hemispheric strokes Patients should be conscious and able to swallow tables CT not used Enrolment within 48 hours | |

| Interventions | T1: atenolol 50 mg po daily T2: slow release propranolol 80 mg po daily C: matching placebo Rx: 3 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Neurological assessments made at days 1 and 8 and months 1 and 6; full functional assessments made from day 8 onwards; death, functional outcome used ADL on an ordinal scale designed for patients with stroke; length of stay Method by which BP measured not given Early and late death and dependency data defined as ADL score of less than or equal to 4 No method given for BP measurements | |

| Notes | Ex: pre‐existing major physical or mental disability, taking beta blockers, contraindications to beta blockers i.e. heart rate ≤ 56 beats/minute, SBP < 100 mmHg, second or third degree heart block, heart failure or bronchospasm causing dyspnoea, history of asthma, insulin dependent diabetes, MI, other causes of seriously reduced cerebral perfusion | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randomisation was done in block of 3 with separate schemes for each hospital |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | High risk | Open randomised controlled trial |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | Unclear from the publication |

Barer 1988/80 mg.

| Methods | As for Barer 1988/50 mg | |

| Participants | — | |

| Interventions | — | |

| Outcomes | — | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | High risk | Open randomised controlled |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | 38 patients lost to follow up |

Bath 2000.

| Methods | Single centre double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Randomisation by computer (with minimisation on age and mean arterial BP) ITT analysis | |

| Participants | UK 37 patients. T: 16, C: 21 Age: T: 76 years, C: 72 years Male T: 6, C: 12 Inclusion: ischaemic or haemorrhage stroke 100% CT Enrolment within 5 days: T: 4 patients enrolled > 5 days and C: 3 patients > 5 days Stroke type assessed clinically | |

| Interventions | T: transdermal GTN 5 mg C: matching placebo Rx: 12 days | |

| Outcomes | 24 hour ambulatory BP was measured before and during GTN treatment at days 0, 1 and 8 Ambulatory BP was monitored using a Spacelabs 90207 set to record thrice hourly during the day and hourly during the night Functional outcome Rankin scale and Barthel Index and case fatality at 3 months Late death and disability used Barthel, but if used Rankin there is 1 less missing value | |

| Notes | Ex: taking part in another trial | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randomisation by computer (with minimisation on age and mean arterial BP) |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Low risk | No loss of follow up |

Bogousslavsky 1990.

| Methods | Single centre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Randomisation by next random number on list 60 patients randomised but 8 excluded due to incorrect diagnosis Data from paper, PP analysis | |

| Participants | German 52 patients: T: 24, C: 28 Mean age T: 64, C: 65 (efficacy) Males 38 Inclusion: ischaemic stroke of mild to moderate severity (Mathew scale sum between 50 and 75), > 39 years and < 85 years Diagnosis: clinical and 100% CT scan Enrolment within 48 hours | |

| Interventions | T: nimodipine 30 mg po qid C: matching po placebo Rx: for 14 days Medical therapy allowed such as drugs against infection, hypertension, mild hypnotics, analgesics, volume substitution (including Dextran 40), low‐dose heparin (2 x 500 U/day) | |

| Outcomes | Impairment: Mathews score on day 1, 3, 5, 7, and 14, week 4 and month 4 BP and heart rate were checked twice daily and on week 4 and month 4 Number of hypotensives noted Method used for taking BP not given | |

| Notes | Ex: TIA, progressing stroke, coma, brain stem, ICH, SAH, recent MI, CCF, systemic infection, renal/hepatic failure, SBP < 100, DBP > 105, bradycardia (heart rate < 50 beats/minute), AV conduction disturbances, concomitant use of CCBs, piracetam, pentoxifylline, naftidrofuryl hydrogenoxalate, dihydroergotoxine, alpha methyl dopa Follow up 4 weeks and 4 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randomisation by next random number on the list |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

Dyker 1997.

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Method of randomisation: computer‐generated random list prepared and held by Pharmacy Trials Department ITT analysis | |

| Participants | UK, single centre 28 patients: T: 14, C: 14 Mean age: 70 years Males: T: 9, C: 8 Inclusion: strokes with mild to moderate hypertension (170 to 250/95 to 120 mm Hg) 100% CT on entry Enrolment within 1 week Patients admitted on prescribed antihypertensive therapy had treatment discontinued for at least 48 hours before entry into the study | |

| Interventions | T: 4 mg perindopril po once daily C: matching placebo Rx: 2 weeks | |

| Outcomes | BP measured semi‐automatically pre‐treatment and hourly to 10 hours repeated at 24 hours and at 2 weeks Clinical and neurological assessment according to the NIH Stroke Scale made before study entry and repeated on day 15 | |

| Notes | Ex: severe carotid disease | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random list prepared and held by pharmacy trials department |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | 28 recruited to the study with 24 completing the protocol |

Eames 2005.

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group Block randomisation (4 per block) | |

| Participants | UK, single centre 37 patients: T: 18, C: 19 Age: 68 years Male: 86% Inclusion: neuroradiologically diagnosed ischaemic stroke with 24 hour BP > 135/85 mmHg Enrolment within 96 hours of stroke onset | |

| Interventions | T: bendrofluazide 2.5 mg po daily C: matching placebo Rx: 7 days | |

| Outcomes | Casual and non‐invasive beat‐to‐beat arterial BP level, cerebral blood flow velocity, ECG and transcutaneous carbon dioxide levels within 70+/‐20 hours of cerebral infarction and 7 days later were measured 24‐hour BP monitoring with Spacelabs 90207 and brachial artery BP with validated semi‐automatic BP monitor (Omron 711) | |

| Notes | Exclusion: history of previous stroke, dysphagia, symptoms lasting < 24 hours, or presented > 76 hours after symptom onset (to allow for 24 hour BP monitoring to be performed prior to randomisation) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Low risk | 38 participants randomised, 19 to each group |

Eveson 2007.

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group Randomisation by prepared and numbered identical study packs | |

| Participants | UK, single centre 40 patients. T: 18, C: 22 Age: T: 73 years, C: 75 years Male: 63% Inclusion: acute ischaemic stroke within the previous 24 hours with a mean casual SBP level ≥ 140 mm Hg or DBP level ≥ 90 mm Hg Randomisation done before neuroimaging and those with non‐ischaemic stroke were withdrawn from the study | |

| Interventions | T: 5 mg lisinopril po once daily C: matching placebo Rx: 14 days Dose was increased to 10 mg or 2 placebos on day 7 if SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg | |

| Outcomes | Casual brachial artery BP monitoring at 5‐minute intervals during a 30‐minute period with a validated monitor (A&D UA 767) NIHSS score at day 14, Barthel score and modified Rankin scale at day 14 and day 90 | |

| Notes | Ex: severe carotid stenosis, significant aortic stenosis, cardiac failure, MI within past 6 months, dysphagia, dehydration, adverse reactions to ACEI, and pre‐stroke modified Rankin score > 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | During 90‐day follow up 1 patient from lisinopril died, 2 placebo‐treated patients underwent rating before day 90 (1 moved to another hospital and 1 declined further study participation after the treatment period) |

Fagan 1988/120 mg.

| Methods | Multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Randomisation technique not stated ITT analysis | |

| Participants | USA, 19 participants Age: > 45 years No genders given Inclusion: IS diagnosed on history and neurological examination Enrolment times not given | |

| Interventions | T: nimodipine (Miles Pharmaceuticals, USA) 120 mg/day po in 6 divided doses C: matching placebo Rx: for 21 days | |

| Outcomes | Brachial BP before and 30 and 60 minutes after each morning dose for 7 days BP methodology not stated DBP estimated from SBP and MAP given in paper | |

| Notes | Ex: concurrent calcium channel antagonists, antihypertensive agents (other than beta blockers) Admission times of concurrent medication always separated from study drug administration by at least 2 hours Part of a larger unpublished trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of nimodipine | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

Fagan 1988/240 mg.

| Methods | Multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Randomisation technique not stated ITT analysis | |

| Participants | USA, 19 participants Age: > 45 years No genders given IS diagnosed on history and neurological examination Enrolment times not given | |

| Interventions | T: nimodipine (Miles Pharmaceuticals, USA) 240 mg/day po in 6 divided doses C: matching placebo Rx: for 21 days | |

| Outcomes | Brachial BP before and 30 and 60 minutes after each morning dose for 7 days BP methodology not stated DBP estimated from SBP and MAP given in paper | |

| Notes | Ex: concurrent calcium channel antagonists, antihypertensive agents (other than beta blockers) Admission times of concurrent medication always separated from study drug administration by at least 2 hours Part of a larger unpublished trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of nimodipine | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

German‐Austrian 120mg.

| Methods | Multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Method of randomisation not known ITT analysis | |

| Participants | Germany and Austria, 16 centres 482 patients: T: 239, C: 243 Age: 40 to 80 years Inclusion: infarcts in anterior circulation 100% CT Enrolment within 48 hours | |

| Interventions | T: po nimodipine 30 mg qid C: matching placebo Optional concomitant drugs were haemodilution, low‐dose heparin, acetylsalicylic acid, digitalis, diuretics, antihypertensives, and sedatives Rx: 21 days | |

| Outcomes | Modified Mathew scale at baseline and days 1, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21 and 6 months Barthel Index at days 1 and 21. Method for measuring BP not given BP estimated from graphs in paper | |

| Notes | Ex: TIA, progressive stroke, vertebrobasilar ischaemia, coma, intracerebral bleeding or tumour, SAH, pregnancy, cardiac surgery within last 3 months, severe systemic illness, acute severe hepatic disease, bradycardia < 50 beats/minute, hypotension SBP < 100 mmHg, severe AV conduction block, renal insufficiency, severe systemic infections, severe cardiac insufficiency within last 3 months, other CCBs, PTX, naftidrofuryl, fetal bovine serum, piracetam, dihydroergotoxine, steroids and osmotic drugs Data taken from the paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

Gray 2007.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised controlled trial Blinded outcome assessments Randomisation: first 571 patients sealed envelopes, the rest by central randomisation service ITT analysis | |

| Participants | UK, 933 patients T: 464, C: 469 Mean age: 75 years Male: 45% Inclusion: acute ischaemic stroke or primary intracerebral haemorrhage with admission venous plasma glucose 6 to 17 mmol/L Enrolment within 24 hours of stroke onset | |

| Interventions | T: 500 ml GKI (of 10% dextrose, 20 mmol potassium chloride and 16U soluble recombinant human insulin) continuous iv infusion C: 0.9% normal saline Rx: 24 hours | |

| Outcomes | Death at 90 days, European stroke scale score, OCSP subtype, Glasgow Coma Scale at baseline Barthel index, mRS at 30 and 90 days | |

| Notes | Ex: SAH, isolated posterior circulation syndromes no physical disability, pure language disorders, renal failure, anaemia, coma, established history of insulin treated diabetes, previous disabling stroke, dementia or symptomatic cardiac failure | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Treatment allocation was concealed |

| Blinding? | High risk | Probably not done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | Probably not done No loss of follow up for death at 90 days Day 90 mRS missing for 5 patients Day 90 Bartel Index missing for 30 patients |

Herrschaft 1988.

| Methods | Single centre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Randomisation technique not stated PP analysis FU: 4 lost | |

| Participants | German 44 participants: T: 24, C: 20 Mean age: T: 59 years, C: 54 years Males: T: 17, C:10 Inclusion: IS diagnosed on neurological examination and 100% CT, first stroke Enrolment within 5 days Proof of vascular stenoses or occlusions of the supplying or intracranial brain vessels by means of doppler sonography or cerebral angiography | |

| Interventions | T and C: continuous iv of 1000 ml Dextran 40 plus 2 x 150 ml Sorbit 40% daily during the first 3 days T and C: over 4 to 6 hours a daily infusion of 500 ml Dextran 40 from day 4 to day 14 T: 3 x 4 g/20 ml piracetam iv bolus day 1 to day 14; FU 28 days C: matching placebo T: 4.8 g piracetam po daily for following 14 days C: matching placebo po daily for following 14 days | |

| Outcomes | Neurological and psychiatric assessments using own scales at baseline and days 7, 14, 28 Organic brain psychosyndrome was determined using Lehrl and Erizgkeit short syndrome test Method of measuring BP not known | |

| Notes | Ex: patients with severe internal disease (heart and lung disease), liver or renal insufficiency, DM, fixed hypertonia, neoplasia, hematological and systemic diseases, patients who had earlier neurological diseases of a different nature, drug or alcohol abuse 4 patients were lost to follow up for following reasons: cardiac insufficiency, cardiac infarctus, pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleeding (T:1, C:3) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | High risk | 4 lost to follow up |

Hillis 2003.

| Methods | Pilot randomised controlled trial Method of randomisation not known FU: no losses | |

| Participants | USA, single centre 15 patients: T: 9, C: 6 Age: T: 59.1 years, C: 67.8 years Male: T: 2, C: 2 Inclusion: IS > 20% diffusion‐perfusion mismatch, quantifiable, stable or worsening aphasia, hemispatial neglect and/or hemiparesis Enrolment: up to 7 days from the onset of stroke symptoms Patients on any previous antihypertensive medication were discontinued prior to the initiation of the study 100% CT, MRI | |

| Interventions | T: iv phenylephrine was titrated to reach 10% to 20% increase MAP and continued for maximum of 72 hours After 24 hours the patients were started on midodrine (up to 10 mg ), fludrocortisone (up to 0.2 mg) and sodium chloride tablets while simultaneously weaning the iv phenylephrine By 4 weeks, midodrine, fludrocortisone, and sodium chloride were tapered as long as there was no concomitant clinical deterioration C: conventional management | |

| Outcomes | MAP measured BP measurement method not given NIHSS and cognitive tests on day 1, day 3 and 6 to 8 weeks | |

| Notes | Exclusion: CI or inability to tolerate MRI, cardiac ejection fraction < 25%, recent congestive heart failure, myocardial ischaemia, unstable angina, bradycardia, allergy to gadolinium, haemorrhage seen on initial CT, agitation requiring ongoing sedation, or MAP > 140 with no intervention | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear from the publication |

| Blinding? | Low risk | Probably done |

| Completeness of follow‐up | Low risk | 15 patients (T: 9, C: 6) no loss of follow up |

Hsu 1987.

| Methods | Multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Randomisation technique not stated, stratified by thrombotic and embolic stroke ITT analysis | |

| Participants | USA, 5 centres T: 43, C: 37 Mean age: 65 years 49 male, 31 female Inclusion: IS 100% CT pre‐entry Enrolment within 24 hours | |

| Interventions | T: PGI2 (epoprostenol sodium, Upjohn Co, USA, and Wellcome, UK) iv infusion started at 1 ng/kg/min increased every 30 minutes until maximum rate of 10 ng/kg/min; infusion for 72 hours with gradual reduction of dose during last 12 hours C: solvent Rx: 3 days | |

| Outcomes | Death at 4 weeks (Neurological impairment assessed using Turnhill score at entry, day 3, weeks 1, 2 + 4) Method of BP measurement not known | |