Abstract

Highly infectious diseases can spread rapidly across borders through travel or trade, and international coordination is essential to a prompt and efficient response by public health laboratories. Therefore, developing strategies to identify priorities for a rational allocation of resources for research and surveillance has been the focus of a large body of research in recent years. This paper describes the activities and the strategy used by a European-wide consortium funded by the European Commission, named EMERGE (Efficient response to highly dangerous and emerging pathogens at EU level), for the selection of high-threat pathogens with cross-border potential that will become the focus of its preparedness activities. The approach used is based on an objective scoring system, a close collaboration with other networks dealing with highly infection diseases, and a diagnostic gaps analysis. The result is a tool that is simple, objective and adaptable, which will be used periodically to re-evaluate activities and priorities, representing a step forward towards a better response to infectious disease emergencies.

Keywords: Steering Committee, Crimean Congo Haemorrhagic Fever, Haemorrhagic Fever Virus, Crimean Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus, Steering Committee Member

In recent years, public health systems worldwide have been challenged by epidemics of emerging infectious diseases, the most notorious of which is the 2014–2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) emergency (Ebola Situation Report 30 March 2016), as well as the ongoing Zika outbreak in Central and South America (Zika situation report 11 August 2016). In an effort to improve the global capacity to respond rapidly and effectively to such threats, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Commission (EC) have set up strategies to identify research and development (RD) needs to rapidly fill gaps and improve collaboration and coordination of response activities (WHO ‘Blueprint for R&D preparedness ad response to public health emergencies due to highly infectious pathogens’ 2015, Kieny 2016).

The EC has been active for years in the fight against emerging infectious diseases, through the funding of networks of European high containment laboratories involved in public health response: the European Network of Biosafety Level-4 laboratories (BSL-4) (www.euronetp4.eu) (Ippolito et al. 2008, 2009, Nisii et al. 2009, 2013, Senior 2008, Thibervilla et al. 2012), and QUANDHIP (Quality Assurance exercises and Networking on the detection of Highly Infectious Pathogens), which resulted from the combined forces of European BSL-4 and -3 laboratories [Nisii et al. 2016]. In the framework of its Public Health Programme, and in compliance with Decision 1082/2013/EU on serious cross-border threats to health (Official Journal of the European Union, 2013] the EC renewed its support of the activities of European high containment laboratories by launching a Joint Action named EMERGE (Efficient response to highly dangerous and emerging pathogens at EU level) (www.emerge.rki.eu/Emerge/EN/Home/Homepage_node.html). The overarching goal of EMERGE is to improve the coordination and preparedness of the public health stakeholders involved in the response to cross-border emerging health threats in Europe through the organization of Quality Assurance Exercises (EQAEs) and training, as well as to promote integration with other key European networks and research projects. EMERGE was launched in June 2015, and in the first months it concentrated on developing a strategy to determine which pathogens should be the focus of the EQAEs and other preparedness activities, using a simple, yet objective and methodical assignment of priority.

Methodology for Pathogen Selection

The Steering Committee (SC) of EMERGE, made up of representatives of the coordinators (the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin and the ‘L. Spallanzani’ National Institute for Infectious Diseases in Rome), and other partner institutions in the United Kingdom, Sweden, France, the Netherlands, and Germany, worked together to develop an assessment method for prioritising agents of highly infectious diseases, which resulted in a list of pathogens with the potential to cause cross-border outbreaks in Europe. What was needed was a set of objective criteria that would function as a tool consistent enough to ensure objectivity, but also flexible enough to be adapted to future, unforeseen scenarios. The potential to cause harm and to spread across borders was further broken down into several variables: severity of disease, risk of introduction into European countries, presence of reservoirs or vectors, size of the susceptible population, existence of prophylaxis or treatment options. A four-tiered scoring system was proposed whereby every single aspect was rated (from 0 to 3) to obtain a number resulting from the sum of all the individual scores. A survey was produced and disseminated to the BSL-4 laboratories that form the SC to collect their individual evaluations, which were summed up to obtain a final score and weighted average representing the consensus of the EMERGE SC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Individual scores attributed to viral agents with cross-border threat by the EMERGE consortium, and their weighted average

| Agent | INMI | Marburg | FHOM | PHE | INSERM | Weighted averagea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Germany | Sweden | UK | France | ||

| Filoviruses | ||||||

| Ebola Zaire | 9 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 8.6 |

| Ebola Sudan | 9 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 8.4 |

| Ebola Cote d’Ivoire | 9 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 7.4 |

| Ebola Bundibugyo | 9 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 8.4 |

| Marburg | 9 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 8.4 |

| Arenaviruses | ||||||

| Lassa | 8 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 8.6 |

| Junin | 8 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 7 | 9.2 |

| Machupo | 8 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 8.8 |

| Guanarito | 8 | 9 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 8.6 |

| Sabia | 8 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 6 | 7.6 |

| Lujo | 8 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 3 | 7.0 |

| Bunyaviruses | ||||||

| CCHF | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 11.8 |

| Coronaviruses | ||||||

| MERS | 8 | 7 | 7 | 10 | Not scored | 8.0 |

| Orthomyxoviruses | ||||||

| HPI | 14 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 16 | 12.8 |

| Paramyxoviruses | ||||||

| Nipah | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7.8 |

| Hendra | 7 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 7.4 |

| Orthopoxviruses | ||||||

| Monkeypox | 7 | 9 | 8 | 7 | Not scored | 7.7 |

| Cowpox | 8 | 10 | 10 | 7 | Not scored | 8.7 |

CCHF crimean-congo haemorrhagic fever, MERS middle east respiratory syndrome, HPI highly pathogenic influenza

aTo calculate the weighted average, the sum of individual scores was divided by the number of respondents, as not all pathogens were scored by all laboratories

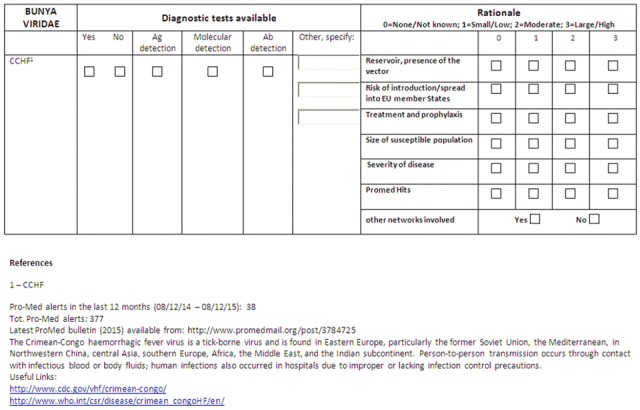

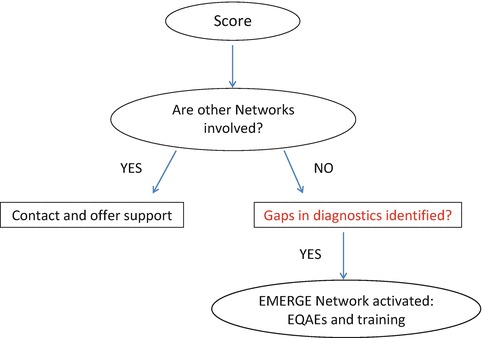

The form used in December 2015 for Crimean Congo Haemorrhagic Fever virus (CCHF) is shown as an example; basic information, useful links, and the number of ProMed posts are also reported on the form (Fig. 1). The use of ProMed as an indicator of severity or threat posed by an outbreak has been a matter of discussion because of the difficulty in setting objective and consistent thresholds in a scoring system. The final decision was to provide the total number of events together with those published in the previous year, asking questionnaire respondents to provide a score from 0 to 3. The EMERGE survey was also used to collect information on the diagnostic methods available in every laboratory, as this information is necessary to complete the decision making algorithm: once the SC has identified a pathogen with a score indicating significant dangerousness and cross-border potential, the evaluation process will enter the next phases: (i) verifying that there are no other networks dealing with the agent in question, and (ii) identifying any gaps in laboratory diagnostics (Fig. 2). These two steps in particular are necessary to optimize resources and avoid duplication of activities: for example, Highly Pathogenic Influenza (HPI) and Ebola viruses were not included in the 2016 activity planning on the grounds that very large networks on Influenza are in existence [Surveillance and laboratory Networks on Influenza (website)], and that no considerable gaps in diagnostics exist for EVD owing to the extensive effort made to tackle the recent emergency.

Fig. 1.

Example of the form sent in December 2015 to BSL-4 laboratories forming the Sterring Committee of EMERGE. It contains general information and number of ProMed posts (bottom), and was used to collect data on diagnostic tests available at each laboratory (top left), and the rationale for including each virus, based on a four-tiered scoring system. Respondents were also asked if they were aware of the existence of other networks dealing with the pathogen (top right)

Fig. 2.

Algorithm used by the EMERGE consortium for the selection of pathogens to include in the annual work plan, taking into account the score attributed by the Steering Committee members, the lack of other networks and the existence of diagnostic gaps

Results and Discussion

Highly infectious diseases can spread rapidly across borders through travel or trade, and international coordination is essential to a prompt and efficient response. Public health systems must be on the alert and ready to deal with new emergencies that may arise anywhere in the world, therefore developing strategies to identify priorities for intervention measures, rational allocation of resources for research and surveillance, and preparedness planning has been the focus of a large body of research in recent years (Balabanova et al. 2011, Witt et al. 2011, Brookes et al. 2015, Dahl et al. 2015, Kulkarni et al. 2015, Krause et al. 2008, Matthiessen et al. 2016, Ng and Sargeant 2013, Xia et al. 2013, Wallinga et al. 2010).

At the start of its activity, the EMERGE consortium set out to develop its own strategy to prioritize pathogens for its 3-year EQAEs planning, in order to improve diagnostic capabilities. The approach used is based on an objective scoring system, a close collaboration with other networks dealing with highly infection diseases, and a diagnostic gaps analysis. The results were discussed at length by SC members, representatives of the EC and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), in teleconferences and face-to-face meetings. The pathogens chosen for the first year of activities were CCHF, Lassa Haemorrhagic Fever virus, and Orthopoxviruses. As mentioned previously, Ebola was not considered an immediate urgency after the gaps analysis (many commercial kits are available or under development today), but will be re-evaluated annually during the course of the project. CCHF was the virus with the highest score (Table 1) and included as a priority for the 2016 activity planning (having excluded HPI for the reasons explained above); therefore the recent occurrence of an autochthonous infection in Europe is proof of the validity of our work (ProMed 2016). In a ‘One Health’ approach, Orthopoxviruses (Cowpox and Monkeypox) were also chosen (regardless of their relatively lower score) because of their presence in Europe and cross-border potential, and their relationship to the Smallpox virus, in order to improve the ability of European laboratories to deal with a possible bioterrorism event.

Compared to other more complex prioritization strategies (Balabanova et al. 2011, ECDC technical report on best practice for ranking emerging diseases 2015, Dahl et al. 2015, Krause et al. 2008, Ng and Sargeant 2013), the EMERGE consortium used a pragmatic approach to produce a tool that is simple, objective and adaptable to changing circumstances. This paper describes the results obtained for viruses only, but the same approach was used to produce the annual work plan also for highly pathogenic bacteria.

EMERGE is a large EC Health Programme-funded joint action that brings together about 40 nationally appointed BSL-3 and BSL-4 laboratories; the fact that the assessment and selection of pathogens will be repeated at least annually, together with the flexibility of the project (activities can be focused and funds shifted to accommodate changing demands), represents a step forward in the direction of a better response to infectious disease emergencies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Health programme 2014–2020, through the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA, European Commission); EMERGE Joint Action grant number: 677066. INMI received ‘Ricerca Corrente’ grants from the Italian Ministry of Health.

#Other members of the EMERGE Viral Pathogens Working Group:

Paolo Guglielmetti – European Commission, Luxembourg

Cinthia Menel-Lemos – European Commission, Luxembourg

Hervé Raoul – Laboratoire INSERM Jean Mérieux, Lyon, France

Caroline Carbonnelle - Laboratoire INSERM Jean Mérieux, Lyon, France

Kerstin Falk - Public Health Agency of Sweden, Solna, Sweden

Richard Vipond – Public Health England, Porton Down, United Kingdom

Robert Watson – Public Health England, Porton Down, United Kingdom

Roger Hewson – Public Health England, Porton Down, United Kingdom

Markus Eickmann – Philipps Universitat Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Marion P.G. Koopmans – Viroscience, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Contributor Information

Giovanni Rezza, Email: giovanni.rezza@iss.it.

Giuseppe Ippolito, Email: giuseppe.ippolito@inmi.it.

Antonino Di Caro, Email: antonino.dicaro@inmi.it.

References

- Balabanova Y, Gilsdorf A, Buda S, et al. Communicable diseases prioritized for surveillance and epidemiological research: results of a standardized prioritization procedure in Germany, 2011. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes VJ, Hernandez-Jover M, Black PF, et al. Preparedness for emerging infectious diseases: pathways from anticipation to action. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:2043–2058. doi: 10.1017/S095026881400315X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl V, Tegnell A, Wallensten A. Communicable diseases prioritized according to their public health relevance, Sweden, 2013. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebola Situation Report – 30 March 2016, WHO (2016). Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204714/1/ebolasitrep_30mar2016_eng.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2016

- ECDC technical report on best practice for ranking emerging diseases (2015). Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/emerging-infectious-disease-threats-best-practices-ranking.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2016

- Ippolito G, Nisii C, Capobianchi MR. Networking for infectious disease emergencies in Europe. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:564. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1896-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito G, Fusco FM, Di Caro A, et al. Facing the threat of highly infectious diseases in Europe: the need for a networking approach. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:706–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause G, The working group on prioritisation at the Robert Koch Institute Prioritisation of infectious diseases in public health – call for comments. Eurosurveillance. 2008;13:1–6. doi: 10.2807/ese.13.40.18996-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieny MP, Rottingen JA, Farrar J, WHO R&D Blueprint team, R&D Blueprint Scientific Advisory Group The need for global R&D coordination for infectious diseases with epidemic potential. Lancet. 2016;388:460–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni MA, Berrang-Ford L, Buck PA, et al. Major emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases of public health importance in Canada. Emerg Microb Infect. 2015;4:e33. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthiessen L, Colli W, Delfraissy JF, et al. Coordinating funding in public health emergencies. Lancet. 2016;387:2197–2198. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30604-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng V, Sargeant JMA. Quantitative approach to the prioritization of zoonotic diseases in North America: a health professionals’ perspective. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisii C, Castilletti C, Di Caro A, et al. The European network of Biosafety-Level-4 laboratories: enhancing European preparedness for new health threats. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:720–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisii C, Castilletti C, Raoul H, et al. Biosafety Level-4 laboratories in Europe: opportunities for public health, diagnostics, and research. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003105. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisii C, Vincenti D, Fusco FM et al (2016). The contribution of the European high containment laboratories during the 2014–2015 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) emergency. Clin Microbiol Infect 9. pii: S1198-743X(16)30227-0 In press

- Official Journal of the European Union, Decision 1082/2013/EU on serious cross-border threats to health (2013) Vol 56, pp 1–15: Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2013:293:FULL&from=EN. Accessed 1 Sept 2016

- ProMed-mail Post (2016) Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever – Spain. Autochthonous, first report. Available from: http://www.promedmail.org/post/4458484. Accessed 2 Sept 2016

- Senior K. European lab network prepares for high-risk pathogen threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;10:593. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70215-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Surveillance and laboratory Networks on Influenza (WHO) Available from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/influenza/surveillance-and-lab-network. Accessed 1 Sept 2016

- Thibervilla SD, Schilling S, De Iaco G, et al. Diagnostic issues and capabilities in 48 isolation facilities in 16 European countries: data from EuroNHID surveys. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:527. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallinga J, Van Boven M, Lipsitch M. Optimizing infectious disease interventions during an emerging epidemic. PNAS. 2010;107:923–928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908491107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Blueprint for R&D preparedness ad response to public health emergencies due to highly infectious pathogens. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/research-and-development/meeting-report-prioritization.pdf?ua=1]. Accessed 1 Sept 2016

- Witt CJ, Richards AL, Masuoka PM, et al. The AFHSC-division of GEIS operations predictive surveillance program: a multidisciplinary approach for the early detection and response to disease outbreaks. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 2):S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S2-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S, Liu J, Cheung W. Identifying the relative priorities of subpopulations from containing infectious disease spread. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zika situation report 11 August 2016, WHO (2016). Available from: http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/situation-report/7-april-2016/en. Accessed 1 Sept 2016