Abstract

Highly pathogenic avian influenza is an acute respiratory infectious disease caused by some viral strains of avian influenza virus A. Its severity is highly diverse ranging from common cold-like symptoms to septicemia, shock, multiple organ failure, Reye syndrome, pulmonary hemorrhage, and other complications leading to death. According to the laws, human infection of highly pathogenic avian influenza has been legally listed as class B infectious diseases in China. And it has been stipulated that it should be managed according to class A infectious diseases in China.

Keywords: Influenza Virus, Acute Lung Injury, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Avian Influenza, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Highly pathogenic avian influenza is an acute respiratory infectious disease caused by some viral strains of avian influenza virus A. Its severity is highly diverse ranging from common cold-like symptoms to septicemia, shock, multiple organ failure, Reye syndrome, pulmonary hemorrhage, and other complications leading to death. According to the laws, human infection of highly pathogenic avian influenza has been legally listed as class B infectious diseases in China. And it has been stipulated that it should be managed according to class A infectious diseases in China.

Etiology

Morphology of the Virus

H5N1 is categorized into the genus of Influenzavirus A, the family of Orthomyxoviridae, and the order of Mononegavirales, which is a segmented negative single-stranded RNA virus (-ssRNA virus). By electron microscopy, it is demonstrated with a typical sphere shape and a diameter of 80–120 nm. Its nucleocapsid is spirally symmetric with envelope. The isolated strain is initially filament-like with a diameter of about 20 nm and a length of 300–3,000 nm. Under an electron microscope, hemagglutinin protrudes into a homotrimer composed of three non-covalent combined protein molecules, while neuraminidase is demonstrated as a mushroom-like homotetramer with a head and a stem. The virus is composed of an envelope, matrix protein, and viral core, consecutively from external to internal of the virus.

H7N9 is a subtype of avian influenza virus that is categorized into the family of Orthomyxoviridae. Its envelope is covered by two types of surface glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). H can be further divided into 15 subtypes, while N 9 subtypes. All human influenza viruses can cause avian influenza, but not all avian influenza viruses can result in human influenza. Among all avian influenza viruses, H5, H7, H9, and H3 can infect humans, and H5 is highly pathogenic. Influenza virus can be categorized into 135 subtypes by HxNx, including avian influenza virus subtype H7N9. It prevailed in birds with no infection of humans. And its biological properties, pathogenicity, and transmissibility largely remain unknown. H7N9 is a new recombinant virus with its genes from avian influenza virus H9N2. Currently, it has been found with mutation of PB2 gene at the site of 701. Laboratory experiments have demonstrated that the mutated virus is highly pathogenic to Canidae. Mutation of 627 amino acid site is also possible. Therefore, avian influenza virus H7N9 cannot be transmitted from person to person but only from pets or living poultry to person.

Physical and Chemical Properties of the Virus

Avian influenza virus resembles to human influenza virus in their sensitivity to organic solutions such as ether, chloroform, and acetone; heat; and ultraviolet ray. It can be inactivated under sunlight for 40–48 h, and its transmissibility can be destroyed rapidly by common disinfectants, such as sodium chlorate, phenolic compounds, quaternary ammonium disinfectant, formaldehyde solution, and other carbonyl and iodine compounds. Influenza virus can survive 30 days at a temperature of 0 °C, 4 days at 22 °C, and 3 h at 56 °C. However, it can be inactivated at a temperature of 60 °C within 30 min and at a temperature above 100 °C within only 1 min. Compared to human influenza A virus, avian influenza virus has stronger resistance.

Pathogenicity of the Virus

HA on the envelope of influenza virus is an adhesion protein. In a binding way of Neu5Acα2-6Gal, it can bind to the cell membrane at the human respiratory mucosa. The highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus can break through the barrier of species to acquire the capability of binding to receptor of human host cells. Such a change in binding to receptor is the key for human infection of avian influenza virus.

Epidemiology

General Introduction of Its Prevalence

Since the avian influenza virus H5N1 was firstly isolated from chickens in 1995, multiple outbreaks of avian influenza has occurred. On May 9, 1997, a strain of avian influenza virus was isolated from a young child aged 3 years in Hong Kong, which was etiologically defined as avian influenza virus. In the same year in Hong Kong, 18 cases were defined as human infection of avian influenza, with six cases of death. This was the first report about direct human infection of avian influenza, arousing worldwide shock and attention.

In mid-February 2003, two residents in Hong Kong were infected by avian influenza virus H5N1 with one case of death. Since December 2003, outbreaks of avian influenza in poultry have been consecutively reported in Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, Chinese Taiwan, and some provinces of mainland China. Outbreaks of human infection of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 have been continually reported in Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, China, and other Asian countries since late 2003. By January 1, 2012, a total of 583 cases of human infected highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 have been reported across the world, with 344 cases of death and a mortality rate of over 50 %.

On April 5, 2013, human infected avian influenza virus H7N9 was firstly reported in eastern China. Avian influenza virus H7N9 has strong pathogenicity with a high mortality rate. By 4 pm on August 10, 2013, a total of 135 definitely diagnosed cases, including 1 in Chinese Taiwan, have been reported in China, with 44 cases of death and a mortality rate of 32.6 %.

Source of Infection

Domestic Poultry and Wild Poultry

Avian influenza virus commonly exists in many domestic poultries, such as turkeys, chickens, guineafowls, geese, ducks, coturnixs, and parrots. The virus might be carried in their secretion and excretion, feathers, organs, and eggs.

Avian influenza virus H5N1 can infect some wild poultries. Wild water poultries, especially those with asymptomatic infection, play an important role in the natural transmission of the viruses. Wild and water poultries like geese, terns, wild ducks, peafowls, and seagulls, especially migrating water poultries, are more likely to transmit avian influenza virus via excretions carrying the viruses.

Birds

Birds such as swallows, chukars, bar-headed geese, ravens, sparrows, and gray herons can be the source of its infection. Migration of birds plays a significant role in spreading avian influenza viruses.

Route of Transmission

Route of Transmission

Transmission via the Respiratory Tract

The virus can infect humans via inhaling virus-containing droplets and droplet core into the respiratory tract. By such a way of inhaling, the viral particle is inhaled into the human body to cause the disease. Avian influenza virus (AIV) also spreads along with air. Direct contact of human to diseased poultry or asymptomatic infected poultry and their secretions or excretions is a route of transmission. In addition, inhaling of viral particles in contaminated environment is another route of transmission. Subsequently, the viral particles adhere to the respiratory tract to cause the disease.

Transmission via Contact

Indirect or direct contact is also the route of transmission. Close contacts of human to H5N1-infected poultry or their feces can cause the infection. Direct contact and indirect contact of possibly contaminated utensils can self-inoculate the virus into the upper respiratory tract, mucosa of eye conjunctiva, and skin wound.

In addition, avian influenza virus can also be transmitted via the alimentary tract, skin wound, the conjunctiva, aerosol, blood, vertical transmission, laboratory and transportation transmission, as well as nosocomial infection.

Ways of Transmission

It is speculated that human is infected by avian influenza virus mainly via direct contact to the diseased chickens and birds, namely, from poultry to person. It is also speculated that pigs are firstly infected by viruses carried by secretion and excretion of diseased poultry. And then human is infected via contacts to secretion, excretion, blood, skin, and fur of the diseased pigs, namely, from poultry to person via pig. The second way of transmission needs further epidemiological studies to verify. Currently, the evidence for human infection of avian influenza virus H5N1 supports transmission from poultry to person. And the transmission from environment to person is possible, while the transmission from person to person has not been fully proved.

Susceptible Population

It is generally acknowledged that human is not susceptible to avian influenza. Although human infection of avian influenza has broken out in many regions, the case of human infection of avian influenza has been rarely reported. Based on the data of the outbreaks, any age group can be infected and children aged under 12 years occupy a high percentage, but with mild symptoms. Human infection of avian influenza virus has no significant gender difference.

Pathogenesis and Pathological Changes

Pathogenesis

Invasion of avian influenza virus to the human respiratory epithelium can cause flu-like symptoms, viremia, and viral pneumonia. In some serious cases, the patients may die from respiratory failure or multiple organ failure. Following pathological autopsy of a death case from avian influenza in Hong Kong, China, it was discovered that pathological changes at the lungs are typical viral interstitial inflammatory changes, necrosis, and fibrous proliferation. The pathological changes of organs are characterized by diffuse phagocytosis of erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets by macrophages, which is known as reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Such a syndrome is the result of cytokinemia caused by the release of multiple cytokines into blood triggered by infection of avian influenza virus.

Pathophysiology

After invasion of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus into the human body, it replicates and multiplies in large quantities within cells to cause structural and functional damages of infected cells and consequent apoptosis. At the same time, a large quantity of specific proteins of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus acts as a superantigen to activate the immune system and to keep it to be highly active. And large quantities of inflammatory cytokines are released to damage normal human cells and their structure. Statistical analysis has demonstrated that 60–70 % human infection of avian influenza is severe, which may clinically develop into acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Pathological studies have demonstrated that the early changes of pulmonary tissues include pulmonary edema and the formation of hyaline membrane, being consistent with the early manifestations of ALI or ARDS. At the advanced stage, the pathological changes include alveolar injury, erythrocytes and fibrous exudates, hyperplasia of interstitial fibroblasts, and deposition of collagen fibers. The parenchymal cells at the lung, liver, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and adrenal glands are subject to retrogressive degeneration and necrosis. Clinical evidence can also be found consistent to these changes, indicating the occurrence of complicating multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). In some cases, the conditions progress into multiple organ failure (MOF) with an extremely high mortality rate.

Acute Lung Injury

Permeability Change of Pulmonary Capillaries

The possible reasons are as the following: (1) the direct destructive effects of infection of AVI on capillary endothelium; (2) functional increase of vascular permeability mediated by cytokines and inflammatory mediators such as metabolites of arachidonic acid, prostaglandin, leukotriene, and thromboxane; and (3) structural increase of vascular permeability due to injuries of capillary endothelial cells and basement membrane mediated by inflammatory cells, endotoxin produced by Gram-negative bacillus, fibrin and its degradation products, complements, polymorphonuclear granulocytes, platelets, free fatty acid, bradykinin, proteolytic enzymes, lysosomal enzymes, inhaling of high concentration oxygen, and formation of microthrombus.

Injury of Lung Tissue Space and Retention of Edema Fluid

The inflammatory cells pass through infiltrative lung tissue space and release inflammatory mediators to exacerbate lung injury. The injuries of capillary endothelial cells lead to increased permeability and increased fluid overflow. Meanwhile, the lymphatic drainage fails to increase correspondingly, leading to fluid retention. Therefore, interstitial and alveolar edema occurs. In addition, increased permeability of capillary endothelium increases the level of protein in the interstitial fluid to be close to the level of protein in the plasma. The decreased osmotic pressure of plasma within vascular vessels exacerbates interstitial edema. In addition to alveolar collapse as well as increased interstitial negative pressure, edema is further exacerbated.

Injury of Alveolar Epithelial Cells

In the cases with acute lung injury, the inflammatory cells and mediators can directly cause structural and functional damages to type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells, destructed basement membrane, and leakage of tissue fluid, protein, and inflammatory cells into the alveolus. Thus, alveolar edema occurs. Damaged type II alveolar epithelial cells can cause a reduced production of surfactants within the alveolus, impaired sodium icon transportation, as well as weakened or lost function of repairing type I alveolar epithelial cells and synthesizing anti-injury cytokines. All of these changes further exacerbate pulmonary edema and dysfunctional ventilation.

Respiratory Function Change

Increased Ventilation at the Early Stage

Its etiological factors include emotional tension, pain caused by trauma, and hypoxemia. Hypoxemia is the main etiological factor.

Decreased Perfusion of Alveolar Capillaries

In the cases with ALI or ARDS, due to lung tissue space edema and alveolar edema, the alveolus is subject to hyperplasia and hypertrophy of alveolar epithelium as well as formation of alveolar hyaline membrane. The gas exchange between the alveolus and capillary is impaired, with disproportion of ventilation and blood flow. Consequently, serious hypoxemia occurs.

Decreased Functional Residual Capacity

Its etiological factors include as follows: (1) paravascular interstitial edema and the following decreased interstitial negative pressure increase the risk of small airway collapse and consequent atelectasis; (2) pulmonary edema decreases production of surfactant in the alveolus and its activity, which further lead to shrinkage or collapse of the alveolus; and (3) pulmonary vascular congestion and increased pulmonary blood volume.

Decreased Pulmonary Compliance

Pulmonary compliance refers to change of lung capacity caused by change of unit pressure. In the cases with acute pulmonary injury due to infection of avian influenza, their functional residual capacity decreases, with pulmonary interstitial congestion and edema as well as decreased surfactants. Therefore, the pulmonary compliance is subject to decrease. Therefore, oxygen demand in breathing significantly increases, with shallow and rapid breathing and reduced tidal volume. The effective alveolar ventilation decreases to aggravate hypoxia. At the advanced stage, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis occurs to further decrease pulmonary compliance.

Change of Pulmonary Circulation

Hemodynamic Change at Lung

Due to hypoxia, the blood flow is rapid, with shortened time for blood passing through the alveolus. Meanwhile, hyperplasia of the alveolar capillary membrane prolongs the time needed for gas exchange. Therefore, venous blood passing through the alveolus fails to be sufficiently oxygenated, resulting in return of a certain quantity of mixed venous blood into the left heart.

Increased Blood Shunt at the Lung

Blood shunt refers to the percentage of venous blood in the arterial blood, which is normally below 3 %. However, in the cases with acute lung injury or ARDS, disproportional ventilation and blood flow causes insufficient gas exchange in the alveolus. And the venous blood circulating in the capillaries fails to be sufficiently oxygenated. Therefore, obviously increased venous blood is mixed in the arterial blood to flow back to the left heart. In some cases, the blood shunt may increase even to 30 %.

Acid–Base Imbalance

In the early stage after onset, mixed alkalosis may occur in severe patients due to hyperventilation. In the advanced stage, a large quantity of anaerobic metabolites gains their access into blood flow due to severe hypoxia to cause severe metabolic acidosis. In the terminal stage, respiratory failure leads to respiratory acidosis. Therefore, acid–base imbalance in the cases of acute lung injury or ARDS evolves from transient metabolic or mixed alkalosis at the early stage to mixed acidosis at the advanced stage.

Human Infection of Avian Influenza-Related Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS)

Human infection of avian influenza commonly causes systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), which further progresses into MODS. In severe cases, multiple organ failure occurs at the terminal stage.

Pathological Changes

Primary pathological changes of human infection of highly pathogenic avian influenza include severe pulmonary lesions, toxic changes of immune organs and other organs, and secondary infection. The causes of death include: (1) progressive respiratory failure caused by diffuse alveolar injury; (2) multiple organ functional impairment of the liver, kidney, and heart; and (3) compromised immunity and secondary infection.

Lung

Observation by Naked Eyes

By naked eye observation, the lung is subject to swelling, increased weight, obvious consolidation that is more serious at the lower lung lobe, and dark reddish in color. Mild adhesion can be found between the lung and parietal pleura. On the section of lung, blood stasis and edema are obvious, with exudates of light reddish foamy bloody fluid. The trachea and bronchus are subject to mucosal congestion. In their canals, there are light reddish foamy secretions. In the thoracic cavity, a small quantity of light yellowish fluid can be observed.

Light Microscopy

At the early stage, diffuse alveolar injury can be observed at both lungs, characterized by acute diffuse exudation. The alveolar cavity is filled with exudates of light reddish fluid and inflammatory cells in different quantities, mostly lymphocytes, monocytes, plasma cells, and phagocytes, but rarely neutrophils. In the alveolus, there are also shedding, degenerative, and necrotic alveolar epithelial cells. In some alveoli, hemorrhage, cellulose, and hyaline membrane can be observed. In addition, hyperplasia of type II alveolar epithelium can also be observed.

Electron Microscopy

Under an electron microscope, there are injury of alveolar epithelial cells, protein-like fragments in the alveolar cavity, as well as necrotic and apoptotic epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes. The alveolar wall is severely damaged, and lysed erythrocytes can be observed in the alveolar cavity. Nuclear margination is observable in some residual alveolar epithelial cells. There are also expansion of rough endoplasmic reticulum, swelling of mitochondria, and vacuole.

Immune Organs

Lymph Node

The lymphocytes are subject to decrease in quantity and scattering distribution. The lymph sinus is dilated, possibly with focal necrosis. The histiocytes are subject to proliferation, with phagocytosis of erythrocytes and lymphocytes.

Spleen

The spleen is subject to slight swelling and smooth and dark reddish surface. Under a microscope, the findings include blood stasis, edema, expanded red pulp, and atrophic white pulp. Around the white pulp, atypical lymphocytes can be found. In addition, infiltration of small quantities of inflammatory cells can be observed in the splenic sinus, with histiocytosis and phagocytosis of blood cells.

Bone Marrow

In the bone marrow, reactive histiocytosis and phagocytosis of blood cells can be observed.

Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Incubation Period

Human infection of avian influenza might have a longer incubation period than other human influenza, which generally lasts for 1–3 days, commonly 1–7 days but 21 days in some cases. The interval between the familial onset is generally 2–5 days, with a maximum of 8–21 days. The duration of incubation period is related to the virus pathogenicity, the quantity of invading viruses, route of infection, and the immunity of infected person.

Clinical Manifestations

Human infection of avian influenza commonly occurs in winters and springs. It has an acute onset and rapid progress. Within 1 week after onset, the conditions may rapidly progress and deteriorate into acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary hemorrhage, pleural effusion, pancytopenia, multiple organ failure, shock, Reye syndrome, and secondary bacterial infection and septicemia. Death may occur due to these complications.

Severe cases are commonly found in adults with a past history of good health, with higher fever persisting for a long period of time. Nearly all patients with pneumonia receive artificial ventilation, and it is often complicated by ARSD and MODS, with a high mortality rate.

Symptoms and Signs

Fever

Almost all patients with avian influenza experience fever, mostly with a body temperature of mostly above 38 °C and rarely 41 °C. The fever types are diverse, but continued fever, remittent fever, and irregular fever are the most common.

The patients with mild avian influenza experience fever for 1–7 days, mostly 3–4 days. With the conditions improved, the body temperature gradually returns to normal. However, the body temperature of patients with severe avian influenza might rise to above 39 °C within 2–3 days, sometimes even 41 °C. The high fever is persistent. Some patients might experience persistent high fever but gradually drop of the body temperature to normal, with improved toxic symptoms.

Systemic Toxic Symptoms

The patients with avian influenza experience serious systemic toxic symptoms in the early stage after onset, such as headache, fatigue, general muscular soreness, and general upset.

According to the clinical data of 59 cases of avian influenza in Hong Kong of China, Thailand, Vietnam, especially Ho Chi Minh City, and Cambodia, 28.1 % (9/32) of the cases develop headache and 28.9 % of these cases develop general muscle soreness, costalgia, and general upset. But according to clinical data in China, 45 % of the cases develop headache, 40 % muscular pain, 80 % fatigue, and 60 % aversion to cold.

Respiratory Symptom

Symptoms of the respiratory system include respiratory catarrh symptoms, cough and expectoration, dyspnea, cyanosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary hemorrhage, pleuritis, and pleural effusion.

The respiratory catarrh symptoms include rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction and pharyngalgia in some cases. Most patients with avian influenza develop cough and expectoration at day 3 after onset. Cough is paroxysmal and violent, with a small quantity of white or yellowish white mucous sputum. Sometimes, the sputum is bloody. Dyspnea commonly occurs at day 6 after onset, mostly mixed dyspnea characterized by difficulty exhaling and inhaling as well as accelerated respiratory rate.

The patients with avian influenza may develop cyanosis at the lips and skin mucosa. The extensive lung lesions cause decreased proportion of ventilation to blood flow, with consequent occurrence of hypoxemia. As a result, increased hemoglobin reduction in capillaries during the systemic circulation causes the occurrence of cyanosis.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is characterized by progressive dyspnea, with a respiratory rate of above 20 times per minute. The rate is progressively accelerated, which may reach up to 60 times per minute. The patients experience cyanosis, irritation, restlessness, and consciousness disturbance. Refractory hypoxemia may occur. Due to excessive ventilation induced by obvious hypoxemia, PaCO2 is subject to decrease, contributing to respiratory alkalosis.

The patients with severe avian influenza can develop pulmonary hemorrhage due to diffuse alveolar injury and diffuse intravascular blood coagulation. The clinical manifestations include cough-up typical bloody sputum.

In severe cases of human infection by avian influenza, the patients develop pleuritis and pleural effusion at the middle or advanced stage, mostly 6–12 days after the onset. Most patients have rough breathing sound, with accompanying bronchial breathing sound. The breathing sound at the affected lung is weak, with rare moist or wheezing rales but no pleural friction.

Digestive Symptom

Some patients can develop digestive symptoms at the early stage, including poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, diarrhea, and watery stool.

Cardiovascular Symptom

Some patients experience subjective palpitation, often accompanied by precordial upset and chest distress. In severe cases, the patients experience rapid heart rate and decreased blood pressure, which rapidly develop into shock. In rare cases, the patients might be hospitalized due to hypotension and shock.

Neurological Symptom

Some patients may experience neurological symptoms, such as headache, irritation, vomiting, convulsion, and lethargy. In rare severe cases, the patients experience initial symptom of serious diarrhea, with following occurrence of convulsion and coma. Death may occur in such patients.

Multiple Organ Failure

Multiple organ failure includes respiratory failure, heart failure, renal insufficiency or failure, liver dysfunction, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Clinical Staging

The typical course of human infection with avian influenza can be divided into three stages: the early stage, the progressive stage, and the convalescent stage.

The Early Stage

The early stage refers to the initial 1–4 days after the onset. It is characterized by an acute onset with fever as the first symptom and a body temperature of above 38 °C. Other symptoms might also occur, including respiratory symptoms like cough with sputum as well as headache, fatigue, general muscle soreness, costalgia, and general upset.

The Progressive Stage

The progressive stage usually begins at day 5 after the onset and lasts for about 16 days, which may be longer in rare cases. Compared to the patients with SARS, the progressive stage of human infection with avian influenza is longer.

The Convalescent Stage

After the progressive stage, the conditions gradually develop into the convalescent stage, which is usually 22 days after the onset. The patients experience gradual alleviation and absence of toxic symptoms. The body temperature returns to normal and the lung lesions are gradually absorbed and improved. More than 50 % of the patients can be discharged after their convalescent stage lasting for about 2 weeks.

Typing

Based on the severity of clinical symptoms, human infection of avian influenza can be divided into mild, common, severe, atypical, and asymptomatic.

Mild Type

The patients experience mild respiratory symptoms like mild dry cough, no obvious cough, no tachypnea, and no dyspnea. The liver function shows no obvious abnormality. Radiological examination demonstrates no sign of pneumonia. And the prognosis is good.

Common Type

The patients experience typical symptoms of human infection with avian influenza, including fever with a body temperature above 38 °C, headache, general pain, fatigue, dry throat, and poor appetite. The patients may also experience respiratory symptoms including cough with bloody sputum, even shortness of breath and cyanosis. By auscultation, low breathing sound at both lungs can be heard with moist or wheezing rales. X-ray demonstrates shadows at the lungs. The peripheral leukocyte count is normal or slightly decreased and there is no hypoxemia by blood gas analysis. The patients experience no serious complications such as ARDS or multiple organ failure.

Severe Type

Clinically, severe type is common. The conditions develop rapidly with dramatic deterioration and a high mortality rate.

The conditions of severe type may rapidly progress into acute lung injury or ARDS, leading to respiratory failure. Multiple system dysfunction or failure commonly occurs to complicate the conditions. Secondary infection of multiple systems at multiple locations by multiple pathogens may also occur. Most patients of this type die from progressive respiratory failure or multiple organ failure.

The patients with one of the following conditions can be defined as the severe type:

Dyspnea with breathing rate during rest being at least 30/min, accompanied by one of the following conditions: First, X-ray demonstrates multilobar lesions or anterior-posterior X-ray demonstrates a total area of lesions accounting for over one-third of both lungs. Second, the total area of lesions increases by above 50 % within 48 h and by anterior-posterior X-ray accounts for over one-fourth of both lungs.

Obvious hypoxemia occurs with an oxygenation index below 300 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa).

Shock or multiple organ dysfunction syndrome develops.

Invasion of the virus to the central nervous system causes viral encephalitis.

Reye syndrome occurs in children.

Serious secondary bacterial infection occurs, especially septicemia or septic shock.

Atypical Type

Atypical type refers to rare patients with mild symptoms, no fever or only mild upset, and no sign of pneumonia. The patients experience no obvious respiratory symptoms, with favorable prognosis.

Asymptomatic Type

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that rare patients develop no onset of the disease despite of a history of close contact to patient with avian influenza or diseased poultry and positive H5N1 antibody. Clinically, the patients show no obvious symptoms and signs. It has been reported by WHO on January 11, 2006, that two children in Turkey were detected with positive avian influenza virus antibody but show no corresponding symptoms. During the outbreak of avian influenza in 1997 in Hong Kong of China, a nurse with close contacts to patients with avian influenza showed positive H5N1 virus antibody.

H7N9 is a subtype of avian influenza virus. The patients with its infection commonly show flu-like symptoms, such as fever and cough with a small quantity of sputum, and accompanying headache, muscle soreness, and general upset. In severe cases, the conditions progress rapidly, characterized by severe pneumonia, a body temperature persistently above 39 °C, dyspnea, and bloody sputum. The disease can rapidly progress into acute respiratory distress syndrome, mediastinal emphysema, sepsis, shock, consciousness disturbance, and acute renal injury.

Human Infection of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza-Related Complication

Respiratory Complication

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

In China, the patients with avian influenza often develop ARDS 8–11 days after the onset. The typical symptoms include progressive dyspnea and even respiratory distress. With the progress of conditions, the patients develop cyanosis, irritation, restlessness, extensive interstitial infiltration in both lungs, and accompanying dilation of umbilical vein, pleural reaction, or a small quantity of effusion. The condition may further develop into multiple organ failure.

Pulmonary Fibrosis

At the early stage of human infection with avian influenza, the pulmonary interstitium may be involved. But in most patients, the interstitial lesions can be gradually absorbed. In extremely rare severe patients, after pulmonary inflammation lesions are absorbed at the convalescent stage, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis or hyperplasia still remains. The severity of pulmonary fibrosis is related to the severity of pulmonary lesions, age, obviously compromised immunity, and existence of basic disease. In most cases, pulmonary fibrosis can be healed 6 months after discharge from hospital. In rare severe cases, pulmonary fibrosis may persist a longer period of time.

Mediastinal Emphysema and Pneumothorax

The patients with avian influenza show different degrees of inflammatory exudates at lung tissue. Respiratory bronchiolitis obliterans causes breakage of alveolar elastic fiber, which further develops into pneumothorax or bronchopleural fistula. In the cases complicated by secondary lung infection, purulent changes are found to aggravate lung injury. In some patients with prior basic lung disease, such as chronic obstructive lung disease and congenial lung diseases, pneumothorax is more likely to occur. The patients of severe type need treatment of noninvasive or invasive ventilation, which is more likely to induce pneumothorax. The occurrence of mediastinal emphysema and subcutaneous emphysema in patients with avian influenza commonly follows the use of respirator.

Pulmonary Infection

Bacterial Pneumonia

During the progress of human infection with avian influenza, the conditions are more likely to be complicated by infections, especially bacterial pneumonia. Secondary bacterial pneumonia is the main cause of death in patients with avian influenza. The most common pathogenic bacteria include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, or Haemophilus influenzae. Infection of mixed bacteria may occur.

Fungal Infection

The common pathogenic fungi include Candida albicans and Aspergillus. And its incidence rate is related to gender, age, existence of basic disease, nutrition, length of hospitalization, and the use of glucocorticoids.

Hepatic Injury

According to literature reports, 60–70 % of human infection with avian influenza is complicated by liver dysfunction, with slightly increase of ALT and AST. However, in China, almost 100 % of human infection with avian influenza shows liver dysfunction, with slight to moderate increase of transaminase. In some cases, the patients may show moderate jaundice. Liver dysfunction mostly occurs 2–3 weeks after the onset. However, liver function failure has not yet been reported in cases with human infection of avian influenza.

Cardiovascular Complication

Cardiomyopathy

Some patients with avian influenza might develop cardiomyopathy with different severity at different stages, which is clinically characterized by chest distress, precordial upset or dull pain, palpitation, and shortness of breath. About 20–40 % of the patients experience bradycardia, slight to moderate increase of myocardial enzymes CPK and LDH, and ECG abnormality. In some serious cases, the patients experience rapid heart rate and decreased blood pressure, which may develop into shock.

Heart Failure

Some severe cases with human infection of avian influenza might develop rapid heart rate, nodal tachycardia, and acute heart failure at day 10–18 after the onset. Death occurs in such patients due to heart failure or peripheral circulatory failure.

Urinary Complication

A large amount of proteinuria (>3 g/L) occurs in some severe patients with avian human influenza in the early stage of onset. At the same time, they might also develop oliguria without hematuria, symptoms caused by urinary irritation, and abnormal number of serum creatinine as well as urea nitrogen. In other cases in the early stage of onset, decreased proportion of urine, polyuria, and erythrocytes as well as casts in the urine can also be found.

Other Complications

Myositis

In some patients with avian influenza, the conditions may be complicated by myositis, characterized by remarkable tenderness of the involved muscle and swelling muscle with no elasticity. The most commonly involved muscle is at the lower limbs. Some severe cases might also develop myoglobinuria due to rhabdomyolysis, leading to renal failure.

Reye Syndrome

Reye syndrome is one of the common complications in children with avian influenza, with a high mortality rate. It is clinically characterized by nausea and vomiting, followed by symptoms of involved central nervous system, such as lethargy, coma, or delirium. There are usually no localized neurological signs, with jaundice due to hepatomegaly. Laboratory test demonstrates increased pressure of cerebrospinal fluid with normal cell counts and detectable RNA of avian influenza virus H5N1.

Diagnostic Examination

Laboratory Test

Routine Test

Laboratory test demonstrates normal or decreased count of peripheral WBC. In severe type, WBC count and lymphocyte count commonly decrease.

Virus Gene Detection

Gene detection has simple operational procedures but with high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. The detection result can be rapidly harvested. And it represents the orientation of virus detection for avian influenza virus. Quantitative RT-PCR is the best way to detect avian influenza virus at the early stage of infection, with results obtained within 4–6 h. Pharyngeal swab can carry more viruses than nasal swab, with a higher positive rate. But negative finding by just once detection cannot exclude the possibility of virus infection of avian influenza H5N1 virus. Repeated detections are recommended to define the diagnosis.

Virus Isolation

Isolation of avian influenza virus from respiratory specimens such as nasopharyngeal secretion and tracheal aspiration is the classical way to define the diagnosis of human infection by avian influenza.

Serological Test

Double sera should be collected at the early or convalescent stage. Hemagglutination inhibition test, complement fixation test, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be performed to detect the antibody of avian influenza virus. An at least four times increase of the antibody titer is an indicator for retrospective diagnosis.

Radiological Examination

X-ray, CT scanning, and MR imaging are important ways for the diagnosis of human infection by avian influenza and its complication, differential diagnosis, therapeutic assessment, and prognosis analysis.

Imaging Demonstrations

Radiological Demonstrations of Chest

According to the criteria for clinical diagnosis of human infection by avian influenza, radiological finding of infiltration shadow at the lungs is important for early diagnosis of human infection by avian influenza. Consecutive X-rays can demonstrate the dynamic changes of lesions, which is the important way to assess the progress of the conditions, the therapeutic effect, and the prognosis. The radiological demonstrations should be analyzed based on the stages and clinical types.

The Early Stage

At the early stage, commonly at day 1–4 after the onset, the imaging demonstrations are characterized by focal flakes or patches of shadow due to focal consolidation at the lungs. About 90 % of patients with avian influenza within 7 days after the onset demonstrate by CT scanning singular or multiple small flakes of shadow with low-density and poorly defined boundary. Most of the shadow is singular with irregular shape. In some cases, pulmonary markings are subject to increase and thickness with predominately peripheral distribution. In the large flake of consolidation shadow, air bronchus sign is demonstrated. A small quantity of effusion can be demonstrated in the pleural cavity.

The Progressive Stage

Most patients experience aggravation of the conditions 14 days after the onset. Initially, the small flakes of shadows may turn into large flake of multiple or diffuse lesions, which develop from unilateral occurrence to bilateral occurrence, from singular lung field to multiple lung fields. In severe cases, obvious changes can be demonstrated within 1–2 days after the onset. The severe cases develop diffuse infiltrative lesions at unilateral lung or bilateral lungs in large flakes of ground-glass opacity and pulmonary consolidation shadow, with inner air bronchus sign. With the progress of conditions, diffuse consolidation shadows are demonstrated at the lungs, possibly with white lung sign at both lungs.

The Convalescent Stage

The lesions of pneumonia in the cases of human infected avian influenza are gradually absorbed within 15–30 days, and the lesions of most patients can be completely absorbed. However, in rare cases, the lesions are partially absorbed with development of fibrosis or proliferation of pulmonary interstitial tissues. Obvious proliferation of pulmonary interstitial tissues may occur 30–40 days after the onset, firstly occurring as thickening of interlobular septum and intralobular interstitium as well as subpleural arc shape linear shadow. The flakes of shadow at the lungs shrink with increased density, with following occurrence of high-density cord-like or honeycomb-like shadow. In some serious cases, pulmonary interstitial proliferation causes shrinkage of lung volume and shift of mediastinum towards the affected lung. Pulmonary interstitial proliferation may extensively exist at the lungs, characterized by thickening of interlobular septum, intralobular septum, and interstitium as well as subpleural arch shape linear shadow. Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis is characterized by honeycomb-like shadow and referred bronchiectasis. After the conditions remain stable, the lesions begin to be absorbed, with decreased range and decreased density. In some cases, despite no abnormal findings by X-ray, CT scanning still demonstrates light ground-glass opacity, which may remain for a long period of time. Therefore, regular CT scanning is recommended to demonstrate lesions that fail to be demonstrated by X-ray. The reexaminations by CT scanning should be regularly performed till complete absorption of the lesions. During absorption of the lesions, pulmonary interstitial proliferations may be observed (Figs. 18.1, 18.2, 18.3, 18.4, and 18.5).

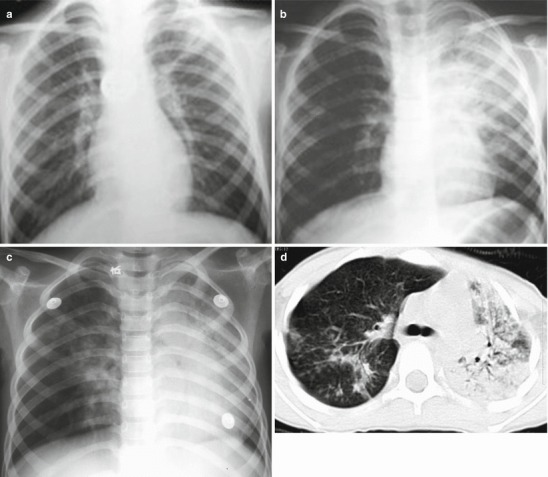

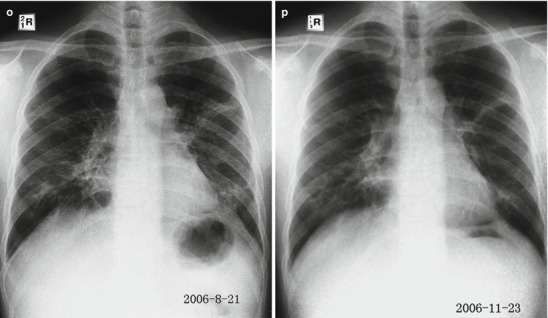

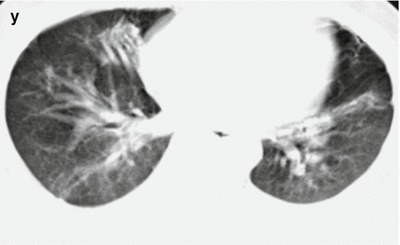

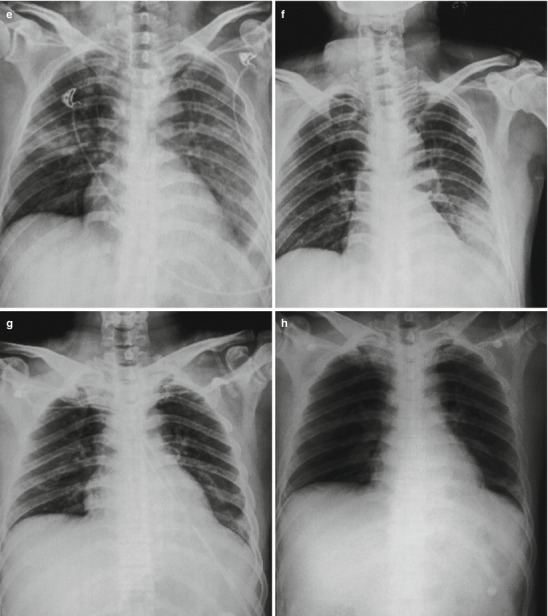

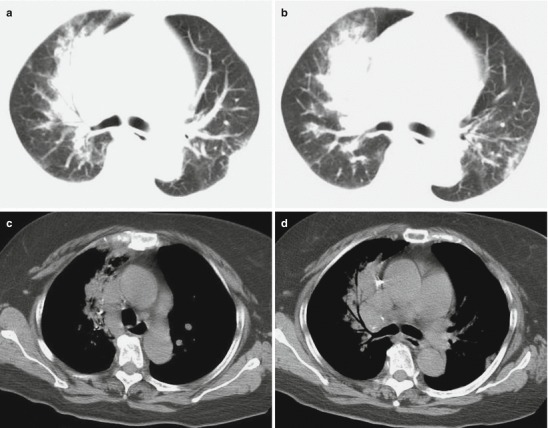

Fig. 18.1.

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza (H5N1). (a) At day 5 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates small flakes of light blurry shadow at the left upper lung. (b) At day 9 after the onset, the lesions at the left upper lung rapidly spread to the upper and middle lung fields with accompanying pulmonary tissue atrophy and collapse and inner air bronchus sign. The right lung is demonstrated with patches of blurry shadow at the medial part. (c) At day 13 after the onset, the lesions at the left lung spread to the whole lung with white lung sign. The pulmonary atrophy and collapse are aggravated. And the right lung is demonstrated with more lesions. (d) At day 15 after the onset, CT scanning demonstrates collapse of the left thorax, large quantities of flakes, and cord-like shadow at the left lung and the upper right lung lobe with inner air bronchus sign. Some pulmonary tissues herniate into the anterior-posterior mediastinum with leftward shift of the mediastinum. (e) At day 22 after the onset, HRCT demonstrates that all lesions at both lungs are absorbed but aggravated atrophy and collapse of the left lung tissue as well as aggravated mediastinal herniation. (f) At day 31 after the onset, the lesions at both lungs are obviously absorbed. The absorption at the left anterolateral lung is more obvious than that at the posteromedial lung. (g) At day 53 after the onset, HRCT demonstrates more cord-like shadow at the left upper lung with grid-like change. The right upper lung lobe is demonstrated with small quantities of cord-like shadow and ground-glass opacity, with leftward shift of the mediastinum. (h) By reexamination after 11 months, CT scanning still demonstrates cord-like shadow and slight leftward shift of the mediastinum

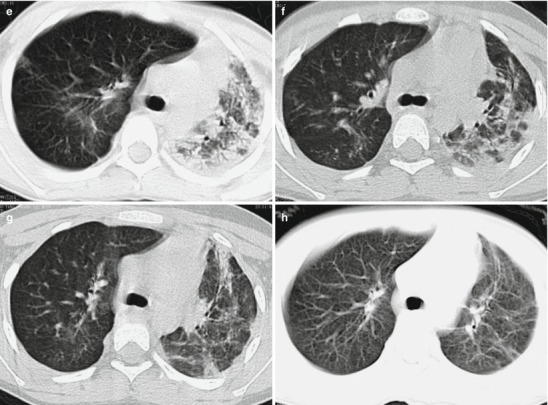

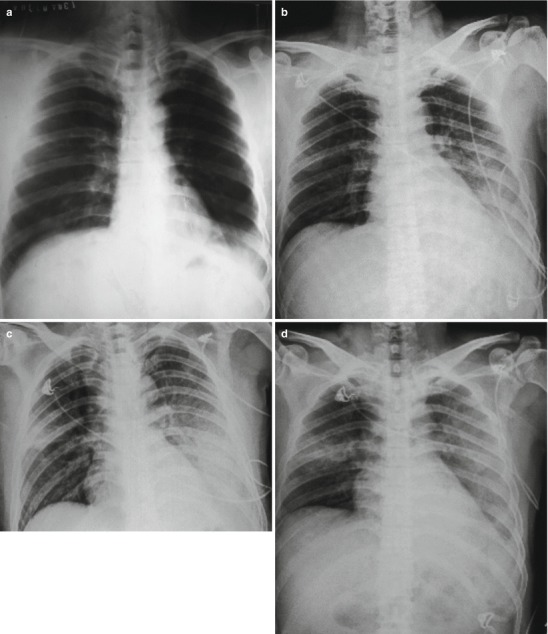

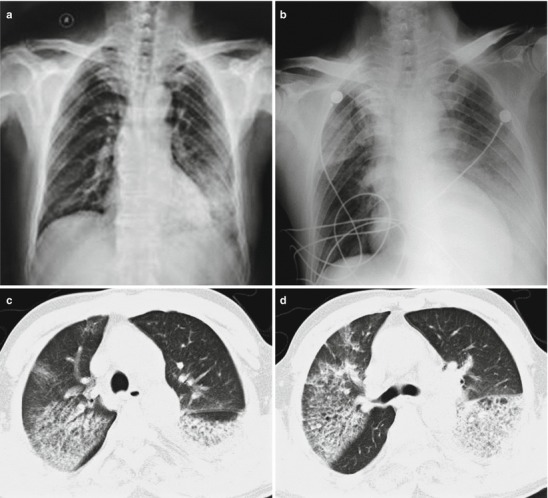

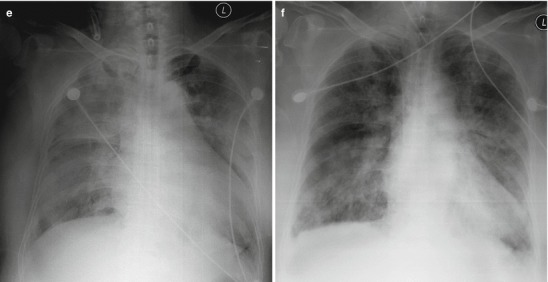

Fig. 18.2.

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza (H5N1). (a) At day 6 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates large flakes of high-density shadow at the left upper lung, patches of blurry shadow at the right upper lung, and slightly narrowed left intercostal space. (b) At day 7 after the onset, the lesions at both lung increase obviously. (c) By reexamination after 8 months, CT scanning demonstrates that some ground-glass opacity and inferior line of the pleura at the left upper lung

Fig. 18.3.

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza H5N1. At day 4 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates diffuse consolidation at both lungs with inner air bronchus sign

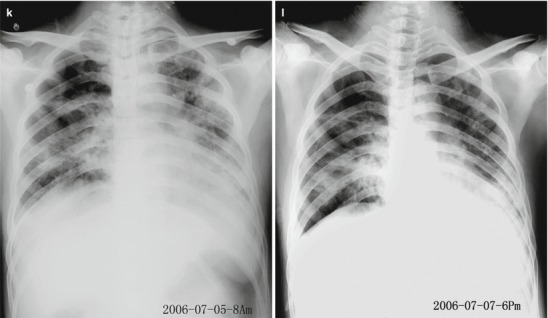

Fig. 18.4.

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza (H5N1). (a) At day 6 after the onset, the left middle and lower lung fields are demonstrated with large flakes of shadows with increased density and poorly defined boundary. Some lesions are demonstrated as ground-glass opacity and the left hilum is poorly defined. (b) At day 8 after the onset, the conditions progress rapidly with large flakes of increased density shadow at the left lung in white lung sign. Flakes of increased density shadow are demonstrated at the right hilar area, right middle lung, as well as middle and medial parts of the right lower lung field. (c) At day 9 after the onset, the left lung field is demonstrated with large flakes of shadow and the right lung is demonstrated with slightly larger range with lesions. (d) At day 10 after the onset, the left lower lung field is demonstrated with slightly light shadow indicating partially absorption of some lesions. The right lung is demonstrated with obviously larger range with lesions. (e) At day 11 after the onset, the left upper and middle lung fields are demonstrated with slightly light shadows. The right lung is demonstrated with continued expansion of the range with lesions of increased density, especially at the right middle and lower lung fields. (f) At day 14 after the onset, the shadows at the left middle and lower lung fields as well as at the middle and lateral parts of right middle and lower lung fields are demonstrated to be lightened, indicating absorption of some lesions. (g) At day 20 after the onset, both lungs are demonstrated with patches of shadows. The middle and lateral parts of both middle lung fields are demonstrated with small flakes of light blurry shadows. The left lower lung field is demonstrated with slight decreased transparency. The left costophrenic angle is demonstrated to be poorly defined. (h) At day 22 after the onset, the right lung field is demonstrated with patches and large flakes of consolidation shadows. The left lung field is demonstrated with diffuse increased density shadows. The left diaphragmatic surface and left costophrenic angle are poorly defined. The conditions progressed. (i) At day 28 after the onset, the left lung is demonstrated with diffuse increased density consolidation. The right lung is demonstrated with large flakes and patches of shadows. Some lung fields are demonstrated with increased transparency. The mediastinum is demonstrated with slight shift leftwards. (j) At day 30 after the onset, the left lung is demonstrated with systemic increased density consolidation shadow. The right lung is demonstrated with large flakes and patches of shadows, with slightly more lesions. (k) At day 32 after the onset, the right middle and lower lung is demonstrated with large flakes and cord-like shadows. The left middle and lower lung is demonstrated with systemic increased density consolidation shadow. The lesions at the right lung and the left upper lung are absorbed, with improved transparency. (l) At day 34 after the onset, the right lung is demonstrated with patches and cord-like increased density shadows. The left lung is demonstrated with systemic light increased density shadows. The lesions at both lungs are obviously absorbed. (m) At day 47 after the onset, the medial part the right lower lung is demonstrated with dense strips of shadows, with poorly defined right heart margin. The left lung is demonstrated with dense cord-like shadows, with well-defined boundary, patches, and spots of shadows as well as less cord-like shadows. (n) At day 53 after the onset, both middle and lower lung fields are demonstrated with less patches of high-density shadows, with scattering cord-like shadows and well-defined boundary. The lesion at the right cardiophrenic angle is demonstrated with cystic dilation of bronchus. Most fields of both lungs are demonstrated with no abnormality. (o) At day 79 after the onset, both lungs are demonstrated with scattering patches and cord-like high-density shadows that are well defined. The lesions are characterized by fibrosis. (p) At day 172 after the onset, both lungs are demonstrated with scattering spots and cord-like high-density shadows with well-defined boundary

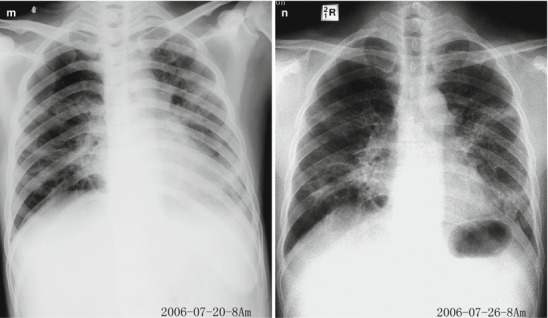

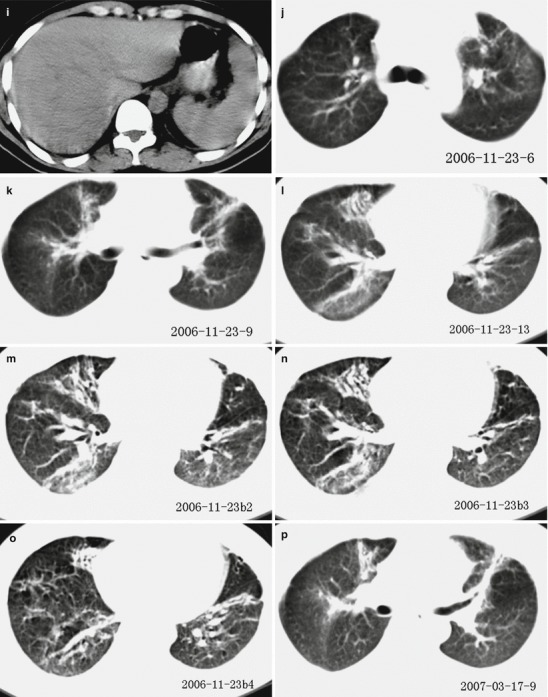

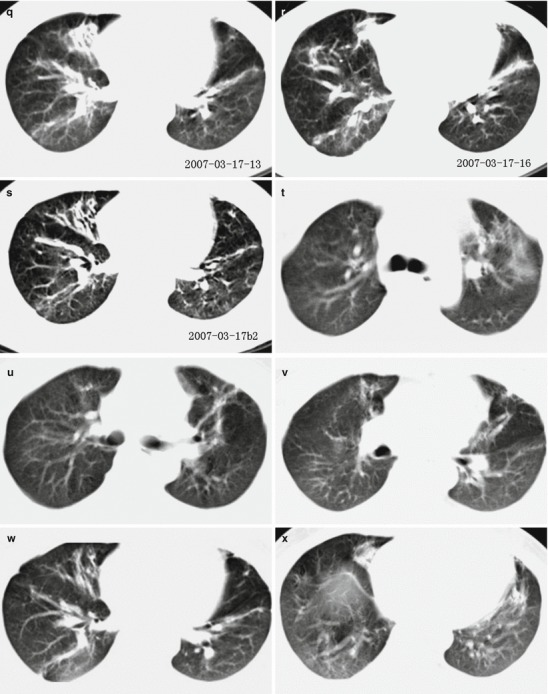

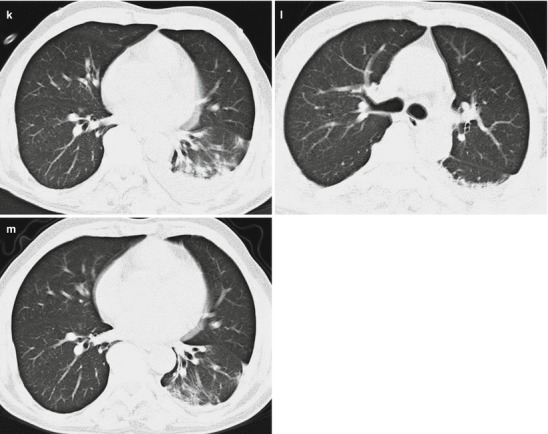

Fig. 18.5.

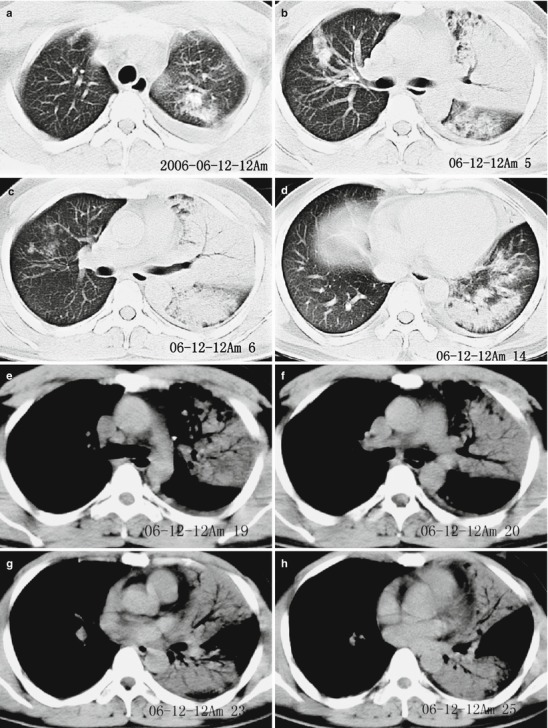

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza (H5N1). (a–h) At day 7 after the onset, CT scanning demonstrates light small flakes of shadows at the posterior segment of the right upper lung lobe and medial segment of the right middle lung lobe. The apical posterior and anterior segments of the left upper lung lobe are demonstrated with irregular small flakes of consolidation shadows. The lingual segment of the upper lung lobe and most segments of the lower lung lobe are demonstrated with large flakes of dense consolidation shadow, with inner air bronchus sign. The left pleural cavity is demonstrated with rare liquid density shadow. (i) The liver and spleen are subject to obvious enlargement and diffuse lesion. (j–o) At day 172 after the onset, CT scanning demonstrates that the lesions at both lungs are fibrous cord-like and grid-like shadows, rigidity of some vascular markings, and no obvious absorption of the lesions. (p–s) At day 286 after the onset, CT scanning demonstrates that the lesions at both lungs are still mainly changes of pulmonary interstitial tissues, such as fibrous cord-like and grid-like shadows, with slow absorption of the lesions. (t–y) At day 730 after the onset, reexamination by CT scanning demonstrates that the lesions at both lungs are still mainly changes of pulmonary interstitial tissues, such as fibrous cord-like and grid-like shadows with rare ground-glass opacity. Compare to previous chest CT findings; the lesions at both lungs are slightly absorbed

Dynamic Change of Thoracic Lesion

Chest X-ray demonstrations of human infected avian influenza are characterized by their rapid change, which is also an important difference from common pneumonia and other atypical pneumonia. At the early and progressive stages, the lung lesions are subject to rapid changes during a short period of time (the shortest period being 12 h), with expansion, perfusion, and migration of the lesions. The shape, range, and location of the lesions may also be subject to changes.

The absorption of lesions generally occurs 14 days after the onset, but in rare mild type of cases, it may occur at day 7 after the onset, with decreased range and density of lesions. For those with favorable therapeutic effect, the large flakes of shadow at the lungs can be significantly changed within 1 day. ARDS is the main cause of death in patients with avian influenza. In severe cases, diffuse alveolar consolidation and ground-glass opacity can be demonstrated at the lungs. Preliminary observations demonstrate that in the cases of death extensive pulmonary consolidation and white lung sign are commonly demonstrated during the progressive stage.

Characteristic Radiological Demonstrations of Chest

At the early stage after the onset, large flakes of shadow with increased density and ground-glass opacity can be demonstrated at the lungs.

The invasion to lung tissues by avian influenza virus is extensive, characterized by multilobar, multi-segmental, diffuse exudative lesions at both lungs. At the peak of their development, white lung sign can be demonstrated.

Rapid development of the lesions is demonstrated by radiological examination.

Both pulmonary parenchyma and interstitium are simultaneously involved. Therefore, chest radiology is characterized by alveolar exudation and pulmonary consolidation.

Slow absorption of the lesions is demonstrated.

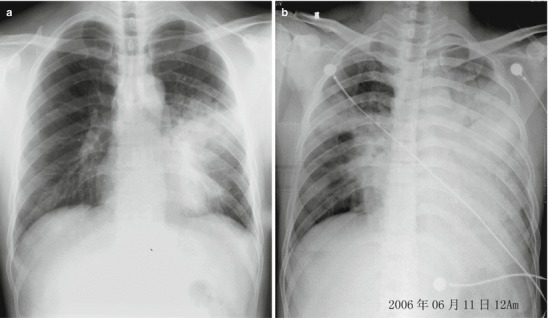

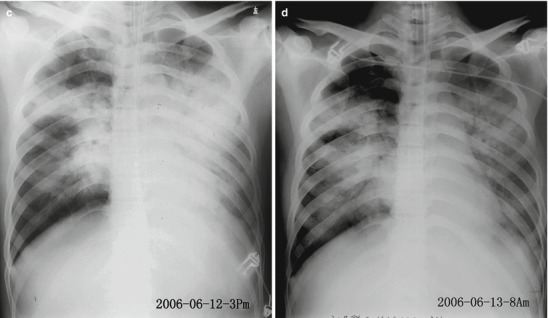

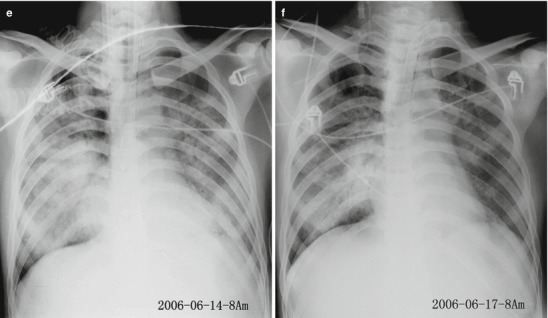

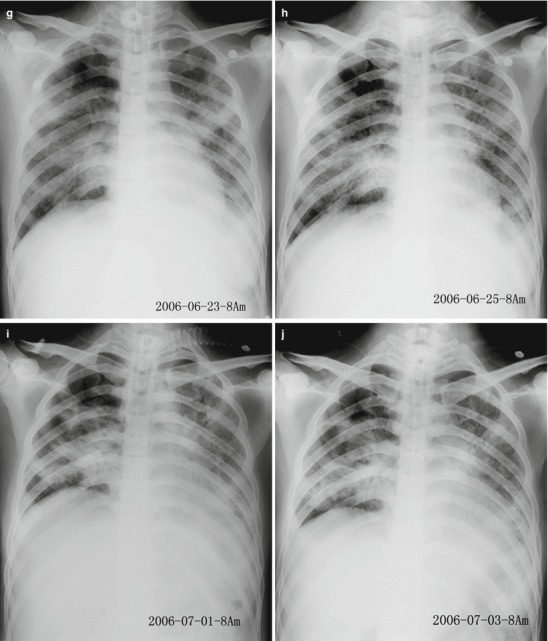

Case Study 1

A boy aged 6 years complained of fever and cough for 15 days, which aggravated with accompanying chest distress, shortness of breath, headache, and muscle soreness for 1 week. He lived in a region with deaths of diseased chicken and ducks and he had a history of intake of diseased chicken and duck. Real-time PCR of pharyngeal swab and RT-PCR demonstrated positive nucleic acids of avian influenza virus H5N1. His mother died from respiratory failure on the day when the boy experienced the onset 7 days after her complaint of high fever and cough.

Case Study 2

A boy aged 9 years complained of cough for 8 days and fever for 4 days. He lived in a region with recent deaths of diseased duck and he had a history of intake of dead duck. By laboratory test, his pharyngeal swab and serum test demonstrated negative H5N1 virus. And paired serum at the advanced and convalescent stages demonstrated above 4 times increase of the specific antibody against H5N1.

Case Study 3

A girl aged 12 years who was the elder sister of the boy in Case Study 2 complained of fever for 5 days, cough and cyanosis at the lips for 2 days, as well as dyspnea for half a day. She lived in a region with recent deaths of diseased duck and she had a history of intake of dead duck. By laboratory test, serum test demonstrated negative H5N1 virus. At day 5 after the onset, her conditions aggravated and death occurred due to multiple organ failure.

Case Study 4

A male patient aged 47 years who was a driver experienced onset on June 6, 2006, and was hospitalized due to fever and cough. He denied a definite epidemiological history. Laboratory test demonstrated positive H5N1 virus.

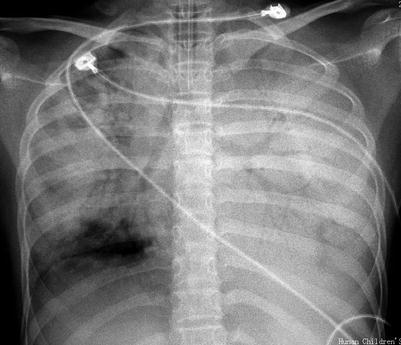

Case Study 5

CT scanning demonstrations of Case 4.

Imaging Demonstrations of Human Infected Avian Influenza (H7N9)

The cases complicated by pneumonia are radiologically demonstrated with flakes of shadow at the lungs. In severe cases, the conditions progress rapidly, with ground-glass opacity, pulmonary consolidation shadow, and accompanying small quantity of pleural effusion (Figs. 18.6, 18.7, 18.8, and 18.9). In the cases with ARDS, the lesions are extensively distributed.

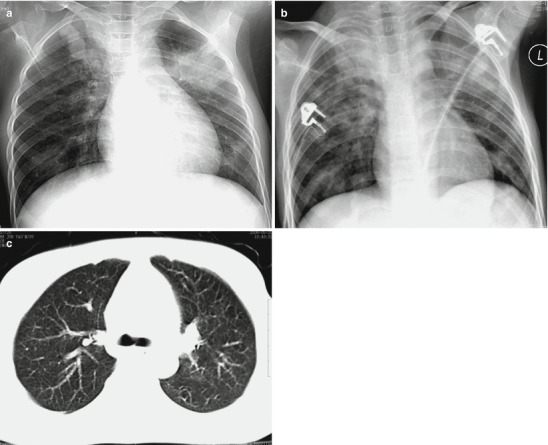

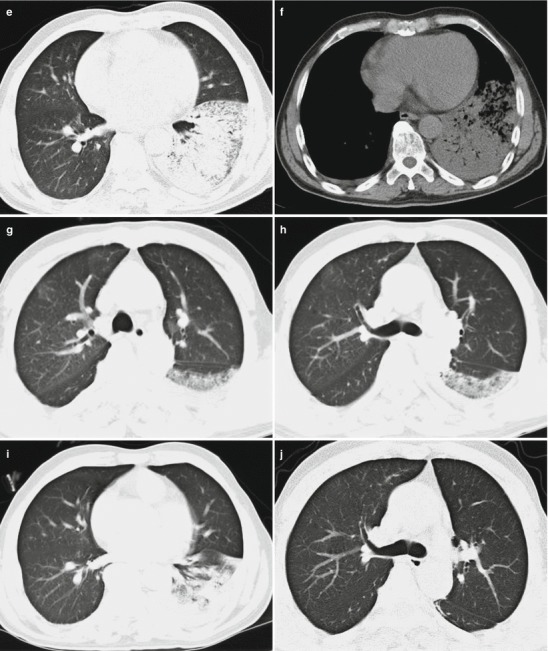

Fig. 18.6.

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza (H7N9). (a) At day 4 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates small flakes of dense shadow at the left lower lung field and small flakes of light blurry shadows at the right lower lung field. The left costophrenic angle is poorly defined and the pulmonary markings at the right lung are also enhanced. (b) At day 5 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates large flakes of dense shadow at the left middle and lower lung fields as well as scattering patches of shadows at the right lung. The conditions progress. (c) At day 6 after the onset, the range with lesions at the right lung is enlarged. (d) At day 7 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates strips of dense shadow at the right middle lung field with inner cavity-like lesion. The conditions progress. (e) At day 8 after the onset, the lesions show no obvious change. (f) At day 12 after the onset, the lesions are obviously absorbed, but dense shadows are demonstrated at the lateral part of the left lower lung field. (g) At day 14 after the onset, the lesions at the left lower lung field are absorbed obviously. (h) At day 18 after the onset, the lesions at both lungs are completely absorbed, with clearly defined lung markings and no enlarged hilar shadow (Note: The case and the figures were provided by Zhao QX and Yang YJ from Infectious Diseases Hospital, Zhengzhou, Henan, China)

Fig. 18.7.

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza (H7N9). (a) At day 4 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates large flakes of high-density shadows at the left lower lung field and overlapping of some lesions with the heart shadow. (b) At day 5 after the onset, X-ray demonstrates large flakes of ground-glass opacity and consolidation shadows at the left lung. The left costophrenic angle and diaphragmatic surface are poorly defined. The right upper lung field is demonstrated with large flakes of increased density shadows with thickened horizontal fissure. Compared to the previous X-ray finding, the range with lesions at both lungs is obviously enlarged. (c–f) At day 6 after the onset, CT scanning demonstrates flakes of ground-glass opacity at the right upper lung and left lower lung, with consolidation shadow at the left lower lung and a little pleural effusion at the right side. (g–i) At day 12 after the onset, reexamination by CT scanning demonstrates that the lesions at the right lung are basically absorbed while most of the lesions at the left lower lung are absorbed, but still with patches of shadows. The clinical symptoms are obviously alleviated. (j, k) At day 18 after the onset, CT scanning demonstrates slight absorption of the lesions at the left lung and left pleural effusion. (l, m) At day 25 after the onset, chest CT scanning demonstrates the lesions at the left lung continue to be absorbed and left pleural effusion is absorbed apparently

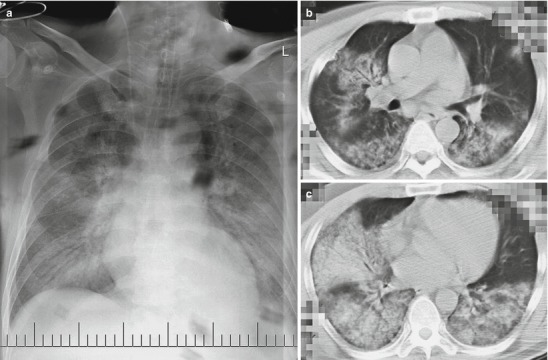

Fig. 18.8.

Pneumonia and pleural effusion complicating human infection of avian influenza H7N9. (a–d) On March 27, 2013, CT scanning demonstrates large flake of consolidation at the right lung with air bronchus sign as well as ground-glass opacity and patches of shadows at both lungs. (e) On March 31, 2013, X-ray demonstrates consolidation shadows at both lungs that are more obvious at the right upper lung and enlarged heart shadow. (f) On April 10, 2013, consolidation shadow at the right upper lung is demonstrated to be absorbed slightly and bilateral costophrenic angles are demonstrated to be blunt (Note: The case and the figures were provided by Tang YH from Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai, China)

Fig. 18.9.

Pneumonia complicating human infection of avian influenza (H7N9). (a) X-ray demonstrates large flakes of high-density shadow at both lungs. (b, c) CT scanning demonstrates consolidation at both lungs (Note: The case and the figures were provided by Cheng JL from the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China)

Case Study 6

A male patient aged 38 years was hospitalized on April 11, 2013, due to the complaints of fever and cough with sputum for 4 days. One week before the onset, he had a history of slaughtering live poultry. On April 8, he developed cough with yellowish sputum, fatigue, chills, and fever with a body temperature of 37.6 °C with no known causes. At a local clinic, he was treated with symptomatic therapy (unknown detailed medication), with poor therapeutic effect. On April 9, he had a body temperature of 38 °C and coughed with yellowish sputum. His body temperature returned to normal after oral medication of nimesulide. On April 11, he developed fever again with a body temperature of 38.5 °C, with cough-up yellowish sputum and pharyngalgia. Both X-ray and CT scanning demonstrated inflammation at the left lower lung lobe. After hospitalization, he was administered with comprehensive treatment, including respiratory tract isolation, oxygen inhalation 2 L/min via nasal catheter, and antibacterial medicine, such as 150 g oseltamivir two times per day, Lianhuaqingwen, clindamycin, sulbactam and cefoperazone, and levofloxacin. He was given standard prevention and respiratory isolation. On April 13, his pharyngeal swabs by local CDC demonstrated negative nucleic acids of avian influenza (H7N9). Routine blood test indicated increased leucocytes and neutrophils, with WBC 11.95 × 109/L, N 91.34 %, L 8.34 %, and PLT 83 × 109/L. X-ray demonstrated remarkably exacerbated lesions at the lungs. On April 15 and April 16, X-rays demonstrated no obvious change and he still coughed with blood-tinged sputum, with no signs of improvement. On April 17, reexamination demonstrated positive nucleic acids of avian influenza (H7N9). Since April 18, the clinical symptoms were improved, with corresponding findings by laboratory test and X-ray. By physical examination on April 25, T 36.7 °C, P 76/min, R 19/min, BP 118/73 mmHg, and SO2 99 %. His cough was alleviated with a little yellowish sputum but with no blood. His pharyngalgia also disappeared. Reexamination demonstrated negative nucleic acids of avian influenza (H7N9). He then was discharged on April 28.

Case Study 7

A male patient aged 65 years experienced dizziness, chills, and fever with a body temperature of 38 °C after he returned home on March 31, 2013. On April 4, 2013, he developed cough with white, thick, blood-tinged sputum, slight shortness of breath after activities, and fever with a body temperature of 39 °C. By physical examination, T 36.5 °C, R 21/min, P 82/min, and BP 118/74 mmHg. Breathing sound at both lungs was rough and breathing movement was bilaterally asymmetric. And he had no definitive history of contact to poultry. By routine blood tests, WBC 2.98 × 109/L, N 72.1 %, and PLT 76 × 109/L. X-ray on April 4, 2013, indicated pneumonia at the left lower lung. On April 6, 2013, an examination of his respiratory tract specimen by RT-PCR demonstrated positive nucleic acids of avian influenza (H7N9). And he was confirmed by CDC of Shanghai, China, to develop human infection of avian influenza (H7N9). After hospitalization, he was administered therapies including oxygen inhalation and anti-viral and anti-infection medications. After treatment, the body temperature returned to normal, and he experienced better spirits and alleviated symptoms, but still coughs with whitish sputum. Reexamination demonstrated negative nucleic acids of avian influenza (H7N9).

Case Study 8

A female patient aged 67 years developed fever with a body temperature fluctuating between 38.7 and 39.0 °C for about 1 week after she returned home from Zhejiang, China. She had no remarkable cough with sputum. By routine blood test, WBC 3.68 × 109/L and N 58.1 %. By routine urine microscopy, erythrocytes 15–20/HP. At a local hospital, she was suspected to have viral upper respiratory infection and was then treated with anti-viral oral medication. After positive therapy, her temperature still fluctuated around 39 °C, and she went to the emergency department of our hospital on March 27, 2013. By auscultation, breathing sound at both lungs is rough with a few moist rales. Chest CT scanning indicated consolidation shadow at the right upper lung lobe, which was suspected to be inflammatory disease. By routine blood test, WBC 5.35 × 109/L and N 68.2 %, and by routine urine microscopy erythrocytes 16–20/HP as well as normal BUN and creatinine. The patient was immediately administered anti-infection and symptomatic supportive treatment. After these therapies, her body temperature failed to return to normal and reached to the highest temperature of 39.5 °C on March 29. She then developed chest distress and cough with rare foamy sputum that is difficult to be expectorated. Meanwhile, hypoxemia occurred. Thus, the administered antibiotic was upgraded to Tienam to fight against the suspected infection. BiPAP and methylprednisolone were also administered to facilitate ventilation, anti-inflammation, and bronchial dilation. After the active therapy, the high body temperature slightly decreased but hypoxemia gradually aggravated. By auscultation, breathing sound at both lungs is rough, with moist rales at the right upper lung. X-ray indicated extensive inflammation at both lungs and lobar pneumonia at the right upper lung. She was immediately offered SIMV + PSV via tracheal intubation and treated with additional medicine including norvancomycin and acyclovir to fight against the infection and virus. Her oxygen saturation fluctuated between 75 and 80 %, indicating severe conditions. And she was transferred to ICU due to suspected diagnosis of severe pneumonia and respiratory failure. By physical examination, T 37.3 °C, P 66/min, R 20/min, and BP 171/84 mmHg. She was unconscious and had cyanosis at lips and weakened breathing movement at the right side. Percussion demonstrated dullness at the right upper lung while clear sound at the other lung fields. The breathing sound was rough at both lungs with moist rales, particularly at the right upper lung. On April 1 after her hospitalization, operational procedures were performed to exclude the possibility of human infected avian influenza but demonstrated positive avian influenza (H7N9) by local CDC. After consultation of experts, the therapies were modified. On April 2013, she underwent tracheotomy but still treated with mechanical ventilation by a respirator. On April 13, 2013, SpO2 decreased to 65 % with fluctuating blood pressure and a minimum of 79/43 mmHg. Her highest body temperature was 40.3. Treated by modified therapies, the heart rate and blood pressure once returned to normal, but finally clinical death was declared after emergency rescuing. On April 1, 2013, laboratory tests were performed. By routine blood test, WBC 7.70 × 109/L, GR 90.4 %, LY 5.8 %, HGB 131 g/L, and PLT 162 × 109/L. By blood gas analysis, pH 7.41, PO2 6.88 kPa, PCO2 6.22 kPa, and SaO2 80.5 %. By blood biochemistry, urea 9.5 mmol/L, Cr 57 μmol/L, UA 216 μmol/L, K 3.86 mmol/L, Na 128 mmol/L, Cl 95 mmol/L, Ca 1.98 mmol/L, P 1.51 mmol/L, and CO2 32.3 mmol/L. On April 13, 2013, by routine blood test, WBC 9.65 × 109/L, GR 93.4 %, LY 2.5 %, HGB 79 g/L, and PLT 79 × 109/L. By blood gas analysis, pH 7.14, PO2 10.45 kPa, PCO2 10.00 kPa, and SaO2 85.3 %. By blood biochemistry, K 6.20 mmol/L, Na 146 mmol/L, Cl 90 mmol/L, Ca 1.88 mmol/L, P 3.88 mmol/L, and CO2 28.4 mmol/L. By detection of inflammatory indicators, PCT 0.14 ng/mL and CRP 43 mg/L.

Case Study 9

A male patient aged 56 years complained of fever for 7 days as well as cough with sputum and chest distress for 3 days.

Imaging Demonstrations of Human Infected Avian Influenza-Related Complications

Pulmonary Interstitial Hyperplasia and Pulmonary Fibrosis

Apparent pulmonary interstitial hyperplasia firstly causes interlobular septal hyperplasia, intralobular interstitial hyperplasia, and subpleural arch shape linear shadow. The flakes of shadows at the lungs shrink with increased density, with gradual development of strips and honeycomb-like high-density shadow at the lungs. Severe pulmonary interstitial hyperplasia causes reduced lung volume and shift of mediastinum towards the affected lung. Pulmonary interstitial hyperplasia may be extensively found at the lungs, characterized by thickened interlobular septum, thickened intralobular interstitium, and subpleural arch shape line. Otherwise, it can be demonstrated as local irregular high-density patches of and cord-like shadows. Intrapulmonary honeycomb-like shadow and referred bronchiectasis are indicators of pulmonary interstitial fibrosis.

Lung Infection

Bacterial Infection

X-ray or CT scanning demonstrates flakes of and mass-like shadows at the lungs.

Fungal Infection

X-ray and CT scanning demonstrate diversified lesions. They may be scattering small nodular shadows at the lungs or patches of shadows at the middle and lower lung fields. Otherwise, the lesions are demonstrated as mass-like or cavity-like shadows or fused lesions into large flakes of shadows in a large range.

Pneumothorax as well as Mediastinal and Subcutaneous Emphysema

Pneumothorax is manifested as shedding of visceral pleura away from the chest wall. By X-ray, it is demonstrated as hairlike linear shadow parallel to the chest wall and no lung markings exterior to the linear shadow. CT scanning demonstrates transparent areas without lung markings at the peripheral thoracic cavity as well as compression and insufficient expansion of the lung.

Demonstrations of mediastinal emphysema by X-ray include vertical gas strip between the heart shadow and the paratracheal soft tissue shadow and linear shadow parallel to the mediastinum form by elevated mediastinal pleura supported by a thin layer of gas. Lateral X-ray demonstrates that the thymus and vascular shadows in the anterior mediastinum are surrounded by gas. Flow of gas at the tangent line in involved subcutaneous soft tissue is demonstrated as cystic or strips of gas containing shadow, with the skin being abnormally elevated and thickened. In the cases with gas gathering at the surface of the pectoralis major, characteristic strips of transparent shadows resembling to fan-shaped distributed muscular fibers are demonstrated at the upper lung fields. CT scanning demonstrates gas density linear shadow around the mediastinum and shift of mediastinal pleura towards the lung field. Gas in the mediastinum flows along the cervical fascia space to the neck and thoracic subcutaneous tissue, thus producing subcutaneous gas density shadow.

Diagnostic Basis

The diagnosis can be defined based on the contact history, clinical manifestations, and laboratory findings. The contact history plays a critical role in the diagnosis of human infected avian influenza.

Epidemiological Contact History

Large quantities of viruses are excreted along with saliva, nasal secretions, and feces from the infected poultry. Direct contact to infected poultry or contact to the utensils contaminated by their feces or secretions is believed to be the main route for spreading avian influenza virus. The following epidemiological data facilitates the diagnosis of human infected avian influenza:

One week prior to the onset, the patients visited the epidemic focus.

One week prior to the onset, the patients had close contact to secretions or excretions from infected poultry.

One weeks prior to the onset, the patients lived nearby an area with the cases of avian influenza or traveled at an epidemic region.

The patients have a history of close contact to patients with avian influenza.

Some patients may have no defined epidemiological history of avian influenza. For those with no direct epidemiological data, the patients should be carefully inquired about contact history to water contaminated by avian influenza.

Human infection of avian influenza spreads from chicken, duck, goose, and other poultries, especially chickens. Therefore, outbreak of avian influenza, especially in chickens, is prior to the outbreak of its human infection. This is an important clue and basis for the diagnosis of human infected avian influenza.

Clinical Manifestations

Incubation Period

The incubation period of human infected avian influenza generally lasts for 1–7 days, commonly 2–4 days but may be as long as 8 days. The interval of its occurrence in family members is about 2–5 days, maximally 8–17 days but may be as long as 21 days.

Clinical Symptoms

Different subtypes of avian influenza virus can cause variant clinical symptoms after they infect human. Avian influenza H5N1 has an acute onset with its early symptoms resembling to common influenza. It is characterized by fever persisting for 1–14 days with a body temperature over 39 °C and maximally 41 °C and accompanying rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, cough, sore throat, headache, muscle soreness, and general upset. In some cases, the patients may develop digestive symptoms including nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and watery stool. Persistent high fever may occur in severe patients, with rapid progress of the conditions into apparent pneumonia, acute lung injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Laboratory Test

Routine Blood Test

The total WBC count is normal or lower than normal, especially with decreased absolute lymphocyte count. The platelet count is normal or is subject to slight to moderate decrease. The decreases of leukocytes, platelets, and lymphocytes, particularly the decrease of lymphocytes, are related to the severity of clinical symptoms and the mortality rate.

Viral Antigen and Gene Detection

Respiratory specimens from patients are collected to detect the antigens of nucleocapsid protein (NP) or matrix protein (M1) or subtype H by immunofluorescence assay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Viral Isolation

Avian influenza virus can be isolated from the respiratory specimen from patients.

Serological Test

The serum-specific antibody of positive avian influenza virus like H5N1 or at least four times increase of antibody titer of avian influenza virus subtype strains in paired serum from the early and convalescent stages facilitates diagnosis.

Radiological Examinations of the Chest

The severe type is demonstrated with:

Diffuse distribution of lung lesions, commonly with large flake of or multiple patches of fused shadows at most of unilateral lung or multiple lobes and segment of bilateral lungs. The diffuse lesions can be demonstrated at the early stage, which persist for a long period of time.

Rapid progress of the lesions, with significant development of the lesions with a short period of time. The focal lesions at the early stage rapidly expand to large flake of diffuse shadow. The density of shadow changes also rapidly, with rapid mutual transformation between ground-glass opacity and consolidation.

The conditions rapidly develop into acute respiratory distress syndrome, with demonstrations of extensive high-density shadow at both lungs.

Differential Diagnosis

Influenza and Influenza Virus Pneumonia

Influenza

Epidemiological History

During epidemic seasons, a large quantity of cases simultaneously develops upper respiratory infection within one working unit or region.

A recently obvious increase of cases developing upper respiratory infection in the local area or adjacent area.

An obvious increasing number of patients pay clinic visit due to upper respiratory infection.

Clinical Symptom

The patients commonly experience an acute onset with symptoms of aversion to cold, high fever, headache, dizziness, general soreness, fatigue, and other toxic symptoms. The patients may also experience respiratory symptoms such as sore throat, dry cough, rhinorrhea, and lachrymation. In rare cases, the patients experience poor appetite, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, vomiting, diarrhea, and other digestive symptoms.

Laboratory Finding

By peripheral blood test, the total WBC count is normal or lower. Influenza virus can be successfully isolated from the nasopharyngeal secretion of patients. An at least four times increase of antibody titer against influenza virus can be detected in serum collected at convalescent and acute stages. Direct detection of the influenza virus antigen in the epithelial cells at the respiratory tract is positive, and the antigen of influenza virus after one generation reproduction by sensitive cells is positive.

Influenza Virus Pneumonia

Influenza virus pneumonia commonly occurs in infants and young children, the elderly and the weak, and patients with chronic disease or compromised immunity. Its incubation period is short, commonly lasting for 1–3 days.

Typical influenza is commonly characterized by acute onset with sudden symptoms of systemic toxic symptoms, such as aversion to cold, chills, high fever, general soreness, severe headache, flushed face, congested conjunctiva, and weakness. But the nasal and pharyngeal symptoms are mild or unremarkable. The respiratory symptoms include gradually exacerbated cough with blood-tinged or bloody sputum, shortness of breath, and cyanosis. The fever commonly persists for a short period of time.

Severe influenza virus pneumonia is demonstrated with obvious pulmonary lesions, commonly with diffuse bubbling and wheezing.

By laboratory test, decreased leukocytes, leftward shift of neutrophil nuclei, and relatively increased lymphocytes can be found.

Radiological examinations of the chest demonstrate scattering cotton-wool-like lesions at both lungs or lesions of interstitial pneumonia.

Etiological test can provide direct evidence to definite the diagnosis of influenza, but with no value for the early diagnosis. Throat lavage fluid for virus isolation is inoculated into chick embryo allantois. Agglutination test is then performed with the throat lavage and chick erythrocytes. However, agglutination inhibition test for chick erythrocytes should be simultaneously performed to exclude nonspecific agglutination. Such a test has a positive rate of 26–50 %. The serum antibody detection, commonly by agglutination inhibition test of erythrocytes or complement fixation test, can be performed simultaneously, with a positive rate of 95 %. Contrast detection should be performed at the early stage and 2 weeks after the onset, and an at least four times increase of the antibody titer has diagnostic value.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Epidemiological History

The patient has a history of close contact to patients with SARS, or he/she is a member of the possibly infected population, or definite evidence has found supporting his/her transmission to others.

One weeks prior to the onset, the patients visited or lived at the region with cases of SARS.

Symptom and Sign

The disease has an acute onset, with fever as its initial symptom and a body temperature of above 38 °C as well as occasional aversion to cold. The patients may also experience headache, joint pain, muscle soreness, fatigue, and diarrhea. Although upper respiratory catarrh symptoms are commonly absent, cough and chest distress may develop, particularly dry cough with a little sputum and occasional blood-tinged sputum. In severe cases, the patients experience rapid respiration, shortness of breath, or apparent respiratory distress. The lung lesions are not remarkable, possibly with rare moist rales or pulmonary consolidation.

Laboratory Test

The peripheral WBC count is normal or decreases and the lymphocyte count commonly drops.

Chest X-Ray