Abstract

Cell fusion is a ubiquitous process fundamental to physiological and pathophysiological events common to multiple cell types and species. Performed ex vivo, cell fusion is a versatile research and therapeutic tool for gene mapping, antibody production, discovering new mechanisms in biological processes, inventing alternative therapies for cell reprogramming, restoring organ function, and creating cellular therapeutics for cancer treatment.

Cell fusion can be successfully applied by creating cellular therapeutic of donor – recipient chimeric cell (DRCC) in the field of solid organ and vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA). Immunomodulatory DRCC therapy has the potential to reduce or even eliminate the need for toxic, life-long immunosuppression and to prevent both acute and chronic rejection. This innovative VCA treatment is a combination of ex vivo created chimeric cell therapy with a short-term selective protocol of monoclonal antibody and Cyclosporine A. The utilization of short-term immunosuppressive protocol will provide the opportunity for chimeric cell engraftment, proliferation, and re-education of recipient’s immune system resulting in prolongation of allograft survival. The use of chimeric cells, as a supportive treatment for VCA, would improve the conditions of severely disfigured patients by offering safe alternative approach and providing better functional and aesthetic results compared to standard reconstructive procedures.

This chapter summarizes the phenomenon, current discoveries, and advancements in the field of cell fusion, as well as introduces ex vivo creation of chimeric cells and presents potential benefits of chimeric cell-based protocols. Successful application of chimeric cell protocol in VCA experimental models will advance the field of reconstructive transplantation towards clinical trials.

Keywords: Donor-recipient chimeric cells, Ex vivo cell fusion, Cellular therapy, Fused cells, Bone marrow, Vascularized composite allotransplantation, Chimerism

The Phenomenon of Cell Fusion

Multinucleated cells, created as a result of spontaneous in vivo cell fusion (CF), were described for the first time in 1839 by Schwann [1]. With the increasing knowledge of the mechanism of CF, the process was defined as an asexual merging of entrapped contents between two or more membrane-enclosed aqueous compartments that involves mixing of the membrane contents and produces mono-or multinucleated cell hybrids [2, 3].

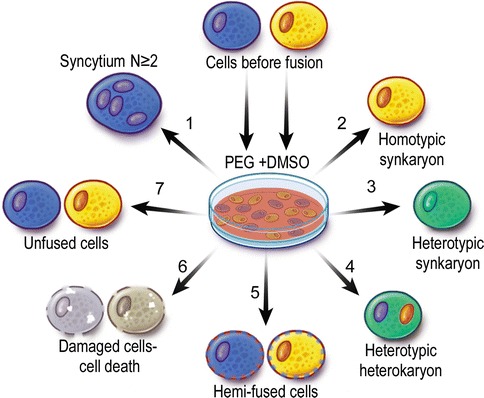

In vivo CF is a multistep process, depending on interplay of many not fully characterized factors, including: priming (preparation of cells for fusion via expression of fusion inducing proteins), chemotaxis (migration of cells towards each other via chemokines expression), adhesion (activation of cell adhesion molecules), fusion, and post-fusion adjustment. Types of cells formed as a result of in vivo or ex vivo fusion can be divided depending on the number and origin of nuclei in the fused cell as well as the type of cells that underwent fusion (Fig. 72.1). Fusion cells can be generated in a homotypic (fusion of cells of the same type) or heterotypic (fusion of cells of different types) fashion [4]. Cells originating from fusion of two different types are known as hybrid cells. Following fusion, cells may contain either one nucleus (synkaryon- created by nuclear fusion) or two or more nuclei (heterokaryon by cytoplasmatic fusion). During the fused cell’s life-time, if both nuclei divisions synchronize, cell can transform from a heterokaryon to a synkaryon cell.

Fig. 72.1.

Types of cells derived as a result of chemical (polyethylene glycol/dimethyl sulfoxide - PEG/DMSO) ex vivo fusion of two different cell lineages. Fusion of cells derived from the same lineages creates syncytium with multiple nuclei N ≥ 2 (1) or with single nucleus – homotypic synkaryon (2). Fusion of cells derived from different lineages creates heterotypic synkaryon (3) or heterokaryon (4). If the fusion of cells derived from different lineages is not complete, hemi-fused cells are created (5). Toxicity of fusion can cause cell death (6). Cells can also not undergo fusion due to lack of other cells in proximity or inappropriate fusion conditions (7)

Most of the knowledge explaining the molecular mechanism of in vivo spontaneous CF, as well as fused cell properties, comes from studies of cancer cell lines [5] and bone marrow transplantation [6]. In 1961 the first in vitro spontaneous CF conditions between mammalian cells were established [7]. The discovery of spontaneous fusion between pluripotent embryonic stem cells and mouse bone marrow cells [8] or brain progenitor cells [9] created an interest in CF as a process that could be applied for tissue regeneration.

CF is considered to be one of the forces altering a cell’s fate by modifying phenotype and function. Multiple in vitro studies demonstrated that hybrids created as a result of fusion are presenting mixed/intermediate phenotype and gene expression patterns derived from both fusion donors in migratory activity [10, 11], proliferation capability [11, 12], cell surface protein expression [8, 9], or drug resistance [13, 14]. The work of pioneers such as Terada [8] and Ying [9] revealed that cells created by spontaneous CF could express phenotype characteristics of undifferentiated cells or properties of both types of cells undergoing fusion. The possibility of formation of stable multinucleated heterokaryons as a result of spontaneous fusion of bone marrow derived cells with several types of fusion friendly cells such as: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, liver, monocytes, mesenchymal stem cells, hematopoietic stem cells/progenitor cells, macrophages, B and T lymphocytes, intestine cells, and Purkinje neurons was confirmed by multiple in vivo studies [6, 15–25]. In these experiments fused cells not only presented mixed phenotype, but also overtook the function of the injured recipient cells and helped facilitate the process of tissue regeneration. The interest in application of bone marrow derived cells in various medical fields such as tissue regeneration and transplantation is increasing due to their potential therapeutic effects.

In Vitro Cell Fusion

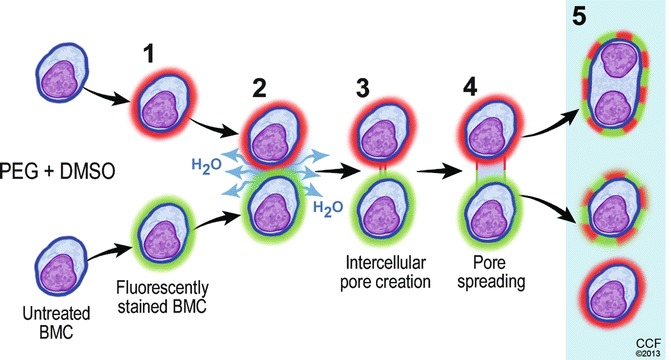

In the early 1960s, in vitro CF was performed to describe the effect of viruses such as hemagglutinating virus of Japan (HVJ) on murine cell cultures [26–28]. Currently, there are three major CF methods: chemical, electrical, and viral. Advantages and disadvantages of each method were compiled and are presented in Table 72.1. New methods of CF applying different agents such as cephalin, bispecific nanoparticles, fusogenic cell lines, or v-fusion are investigated [29–32]. Combining different fusion methods and introducing additional modifications of conventional techniques have been studied to improve the fusion efficacy, either by increasing the cell-to-cell contact capability or permeabilization area. The selection of proper fusion method and protocol optimization depends on the cell type, cell number, culture conditions (monolayer vs. cell suspension), their sensitivity to unfavorable conditions, and equipment availability. The efficacy of polykaryons creation can be controlled by factors such as time and/or fusing agent concentration. Higher numbers of polykaryons can be also generated by repeating the fusion procedure [33]. Additionally, the application of supporting agents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), in case of polyethylene glycol (PEG) mediated fusion, was confirmed to be more efficient in creating higher number of fused cells than using PEG alone [34, 35]. PEG, due to its hydrophobic properties, decreases the distance between cells by removing water (thermodynamically unfavourable environment) and causing their aggregation. Dehydration leads to asymmetry in the lipid membrane bilayers leading to formation of a single bilayer septum at a point of close apposition of two cell membranes and facilitates formation of the pore following septum decay (Fig. 72.2).

Table 72.1.

Comparison of three of the most popular in vitro fusion methods: chemical (polyethylene glycol, PEG), electrical and virus induced fusion applied for creating cell hybrids

| Types of fusion | Chemical fusion – PEG | Electrofusion | Virus induced fusion (biological fusion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Cells are brought closer by removal of water between the cells and further dehydration changes symmetry of lipid membrane | Application of pulsed electric field: Alternating current aligns cells and direct current forms temporary pores in cell membranes | Applies noninfectious or inactivated viruses (Sendai virus-most common use, HVJ, SV5, coronavirus, rhabdovirus) expressing viral envelope glycoproteins |

| Efficacy | Low | High | Low |

| Number of cell types that can be fused during single fusion procedure | Multiple cell types can be fused at the same time | Not more than two cell types during fusion procedure | Not more than two cell types during fusion procedure |

| Equipment | No additional equipment | Fusion chamber | Requires facility to work with viruses |

| Advantages | Fast, cheap and easy | Fast and easy | Less toxic |

| Disadvantages | Cell-type dependent toxicity, depends on shape, size, and intensity of shaking | Cell-type dependent toxicity, similar size cell can be fused, cost | Length of procedure depends on cell type, productions/purchase of inactivated virus, continuous to fuse for a period of time, immunologic reaction, cost |

| Scaling up | Possible | Limited | Possible |

| Clinical application | Possible | Possible | Limited (potential for viral infection) |

Fig. 72.2.

The mechanism of polyethylene glycol/dimethyl sulfoxide (PEG/DMSO) induced donor-recipient chimeric cells creation via ex vivo cell fusion (CF). PEG mediated CF is a three-step process requiring the following: (1) aggregation or “close” (the intercellular distance may vary for different cells and fusion models) approach of membrane lipid bilayers due to hydrophobic properties of PEG that causes membrane dehydration; (2) removal of the water between adjacent cells; (3) the intermediate membrane destabilization (facilitated by PEG) is followed by creation of pores (facilitated by DMSO) in the membranes of cells undergoing fusion; (4) positive osmotic pressure created by PEG improves stabilization of fusion intermediates and leads to expansion of the pores, cell swelling and cell-to-cell fusion. The products of PEG/DMSO solution induced cell fusion may include (5) heterokaryon and synkaryon cells as well as cells that did not undergo fusion process. More detailed descriptions of cell fusion mechanism can be found in articles by Lentz [62, 63]

Application of Cell Fusion as a Research Tool

Ex vivo CF can be a crucial tool in creating new cell types or improving research models used in vitro in the basic mechanistic studies (e.g. cancer research) or for more efficient drug/treatment development. Recently ex vivo CF was applied to create human insulin-releasing 1.1B4 cells, which are able to form pseudoislets [36]. Most of the studies describing interactions and insulin secretion were performed using B cells routinely grown in the monolayers, which can impact their secreting properties. The use of fused cells in this model may improve the knowledge of regulatory mechanism underlying insulin secretion and survival of human pancreatic B cells. Additionally, it can help develop better types of insulin secreting cell therapies against diabetes [36]. CF is a well-established procedure in the process of producing monoclonal antibodies, which are widely used in research application such as protein or cell type detection, blocking cell activity, studying cross-reactivity, and antigen purification. Monoclonal antibodies are produced by immortalized hybridoma cells, which are created by ex vivo CF between antibody secreting B cells and myeloma cells. The first report describing the creation of hybridoma was published in 1973 by Schwaber and Cohen [37] and was soon followed by a procedure of fusion between myeloma cells and B lymphocytes isolated from spleen of immunized animal, in 1975 by Kohler and Milstein [12]. Generated cells were characterized by both lymphocyte properties to produce specific antibodies and the immortal character of the myeloma cells. CF played a critical role in a variety of studies exploring processes such as cancer pathogenesis, explaining trans-differentiation of committed somatic cells through cell reprogramming, or even assessing the effects of nuclear transfer of nucleus of one cell transferred to the cytoplasm of enucleated oocyte [38]. Examples of application of CF in research are presented in Table 72.2.

Table 72.2.

Examples of research studies in which ex vivo CF was applied as a research tool

| # | Study problems utilizing CF as a research tool | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Epigenetic reprogramming | [39] |

| 2 | Genomic instability | [40] |

| 3 | Cancer progression | [41] |

| 4 | Determination of dominance or recessiveness of genes | [42, 43] |

| 5 | Dynamics of intracellular components | [44, 45] |

| 6 | Results of polyploidy | [46] |

| 7 | Hybridomas for monoclonal antibodies production | [12] |

| 8 | Radiation hybrids to map genomes | [47] |

| 9 | Aneuploidy | [48] |

Application of Cell Fusion as a Treatment Option

Clinical application of ex vivo CF has been limited to the scarcity of knowledge of the fusion mechanism, as well as fused cell function and safety. However, CF has a potential to become a useful tool in the armamentarium of highly anticipated methods focused on organ and tissue function regeneration. Currently, CF is utilized either indirectly during production of monoclonal antibodies or directly by creating cellular therapeutics. Monoclonal antibodies are used to treat a variety of diseases and conditions such as cancer, autoimmune disease, inflammation, and transplant rejection. Creation of immortalized hybridomas is an essential part of monoclonal antibody production. Antibodies such as Muromonab-CD3 (anti-CD3) are directly produced by mouse hybridomas [49]. However, basiliximab (anti-CD25), which is a chimeric antibody, is primarily created by mouse hybridoma and further modified by utilizing recombinant DNA technology to replace the mouse immunogenetic component of the antibody with human protein [50].

The concept of direct application of ex vivo CF in creation of cellular therapies was initiated by observations of opposite sex hematopoietic cell transplantation. The ability of transplanted stem cells to fuse spontaneously with defected cells and restore their function originated the research focused on creating cellular therapies. These experimental therapies are oriented towards approaches such as fusion of differentiated cells with stem cells or reprogramming of specialized cells to pluripotent state via CF of embryonic stem cells or embryonic germ cells. In theory, ex vivo CF could be applied as a cell-based gene-delivery system for treating genetic and non-genetic diseases such as muscular dystrophy, tyrosinemia, hemophilia, or diabetes type 1 and 2.

Other approaches, which utilize direct application of CF, can be found in cancer immunotherapy. Anti-cancer vaccines created by ex vivo CF between dendritic cells (DC), which are potent antigen presenting cells, and carcinoma cells are among the most promising strategies dedicated to introduce cancer specific antigens to DC. The aim of this approach is to enhance immune system response against cancer cells. Fusion between DC and tumor cells eliminates the limitation of low number of known tumor-associated antigens available for HLA molecules. Hybrid cells containing unidentified molecules and expressing them in combination with MHC Class I and II molecules in the presence of co-stimulatory signals may be an effective alternative for patients suffering from rare forms of cancer. The results of cancer immunotherapy using anti-cancer vaccines in vitro, as well as in mouse model, showed potent anti-tumor response against multiple tumor-associated antigens [51, 52]. Currently, this immunotherapy is being evaluated in the treatment of melanoma and breast cancer patients in phase II clinical trials.

Cell Fusion in the Field of Transplantation

The infusion of bone marrow-derived cells, presence of chimerism in peripheral blood, and following migration of donor-derived cell to lymphoid organs was associated with prolonged survival of the transplants or even tolerance induction [53–57]. Bonde et al. [58] reported that during co-culturing spontaneous fusion of bone marrow cells derived from two different mice strains occurred. In vivo study confirmed this result following allogenic and syngenic transplantation. Further, it has been shown that fused cells, on their surface, expressed both donor and recipient MHC antigens.

Siemionow’s group also performed experiments on CF of bone marrow derived cells [59]. Results of this preliminary study were in line with results of Bonde et al. [58] and showed that there is a possibility of creating in vivo donor-recipient fused cells that can facilitate face allograft survival (Article in press). Short immunomodulatory protocol of anti-αβ-TCR monoclonal antibody and cyclosporine A was used to facilitate engraftment of spontaneously created donor-recipient chimeric cells (DRCC).

Ex Vivo Cell Fusion as a New Approach for Tolerance Induction

The successful establishment of protocol creating in vivo DRCC either via the mechanism of trogocytosis or spontaneous CF is opening many possibilities of using bone marrow derived cells as a tool for development of novel therapeutic products. Although, further research on DRCC is necessary in order to fully understand the underlying mechanisms of their creation and action in vivo, the creation of tolerance-inducting cells could be a breakthrough modality in solid organ and CTA transplantation.

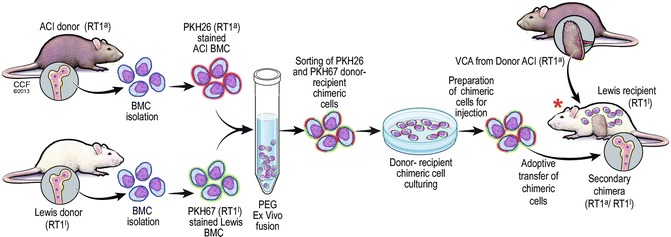

Ex Vivo Creation of the Donor-Recipient Chimeric Cells: Animal Model

There are several disadvantages for creating DRCC in vivo in the clinical scenario as described in the previous chapter (10.1007/978-1-4471-6335-0_71). The most challenging issue in clinical execution of the primary chimera creation protocol is the critical time frame following bone marrow infusion required for development of chimeric pro-tolerogenic environment in the transplant recipient. Pre-treatment of the transplant recipient in order to create in vivo DRCC will be possible only for the living organ donor. To overcome this hindrance and move forward to a more clinically applicable model, Siemionow’s group adopted a new approach to create DRCC via ex vivo CF. DRCC therapy was created by fusion of donor and recipient bone marrow derived cells by polyethylene glycol (PEG) technique. Briefly, bone marrow cells were harvested from the tibia and femur bones of two fully MHC mismatched ACI (RT1a) and Lewis (RT1l) rats using the flushing technique. Next, erythrocytes were removed and white blood cells from each donor were separately stained with PKH26 (red/orange) or PKH67 (green) cell membrane fluorescent dye. Fluorescent staining of cell was applied in order to detect and separate double stained (green and red/orange) DRCC created during fusion using fluorescence activated cell sorting (Fig. 72.3). PEG mediated ex vivo fusion protocol is feasible to be performed in the surgical unit and will provide higher number of DRCC compared to in vivo protocol. This technique does not require cells of similar diameter or specific proportions as in electrofusion [60].

Fig. 72.3.

Experimental model of ex vivo creation of the donor-recipient chimeric cells (DRCC). DRCC will be created ex vivo by the chemical polyethylene glycol (PEG) induced cell fusion of the bone marrow cells harvested from the ACI (RT1a) and Lewis (RT1l) rat donors. Isolated bone marrow cells will be separately stained with two different (red/orange and green) fluorescent dyes. Next, the ex vivo fusion will be performed using PEG. Supportive therapy using the fused DRCC will be given based on the double fluorescent staining and will be injected into the bone of Lewis (RT1l) rat recipients along with the donor matching (ACI) VCA (skin allograft) transplant. * – Seven day protocol of combined αβ-TCR mAb (250 μg/day) and CsA (16 mg/kg/day) therapy

Siemionow’s team successfully confirmed the feasibility of the fusion protocol and creation of the DRCC. The assessment of DRCC confirmed the presence of MHC class I derived from both donors on the surface of chimeric cells as well as the presence of ACI and Lewis-specific genomic sequences. The phenotype evaluation showed that more than 40 % of chimeric cells were CD90 positive. Additionally, mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay showed immunologic unresponsiveness of chimeric cells and colony forming unit assay revealed that chimeric cells are able to create the same types and comparable numbers of colonies as untreated bone marrow cells. DRCC were tested in vivo as a supportive therapy for allogenic vascularized skin allograft under Siemionow’s laboratory seven day immunosuppressive protocol of anti-αβTCR monoclonal antibody (250 μg/kg/day) and cyclosporine A (16 mg/kg/day). The results of this study showed increased survival of the allograft confirming pro-tolerogenic properties of DRCC. Prolonged survival of the fully MHC mismatched allograft was associated with the presence of the donor-derived cells in the peripheral blood and lymphoid organs of the recipient rats. One of the potential DRCC mechanisms of action might be similar to the one observed by Chow et al. where cell expressing recipient MHC were able to avoid detection of recipient immune response [61]. Another possible mechanism can be migration of DRCC to the lymphoid organs such as thymus where these cells affect selection of donor-reactive T cells causing induction of chimerism and acceptance of the allograft.

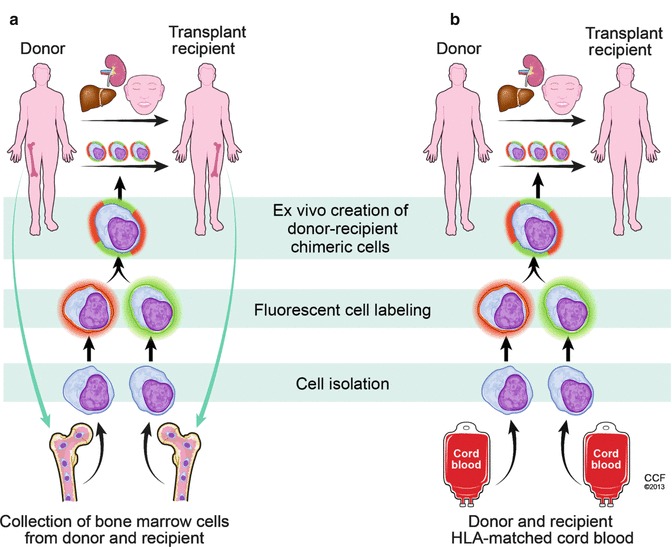

Hematopoietic Donor-Recipient Chimeric Cells from Animal Model to Human

Donor(s)-specific transferable tolerance via DRCC is a new strategy generating custom made cellular therapeutic with a high specificity for an individual patient. Building on the promising results from the in vivo study, Siemionow’s group progressed to testing the feasibility of ex vivo created chimeric cell protocol using human cord blood cells as a proof of concept. The preliminary experiments confirmed the feasibility of Siemionow’s group protocol for creation of chimeric cells. Analysis of DRCC confirmed that fusion can produce viable cells presenting on their surface HLA class I and II characteristics for both of the donors and proliferating capability comparable to untreated cord blood controls. In the future, Siemionow’s group will focus on the creation of DRCC from human bone marrow. Bone marrow will be a primary source of cells for ex vivo CF for the therapeutic purpose as a supportive therapy. In cases where bone marrow is not available (i.e. recipient is suffering from severe bone marrow deficiencies due to gamma irradiation or deceased organ donor) the other alternative will be the use of matched cord blood cells. The possibility of interchangeable application of either bone marrow or cord blood cells will provide assurance that a sufficient number of chimeric cells can be obtained at all times (Fig. 72.4).

Fig. 72.4.

Future applications of the ex vivo created donor-recipient chimeric cells used as supportive therapy in the clinical scenario. Human donor-recipient chimeric cells can be utilized as a supportive therapy for solid organ (living donor- kidney, liver transplantation) and in the future for vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA). Progenitor cells derived from sources such as bone marrow or cord blood will be isolated, fluorescently labeled using two different cell membrane dyes (PKH26 and PKH67), and will be fused ex vivo using PEG technique creating the donor-recipient chimeric cells. Based on the double fluorescent staining, the ex vivo fused chimeric cells will be sorted out and delivered via either the intraosseous or intravenous route to the recipient at the day of solid organ or VCA transplants. Panel (a) – Patients receiving transplant from the living donor will be supported with the bone marrow derived donor-recipient chimeric cells collected from both the donor and the transplant recipient. Panel (b) – If access to the donor and/or recipients bone marrow cells is not possible (i.e. recipient is suffering from severe bone marrow deficiencies due to gamma irradiation or organ donor deceased), the donor and recipient HLA-matched cord blood cells can be used to create an ex vivo donor-recipient chimeric cells and to apply them as a supportive therapy

Siemionow’s group tolerance inducing protocol of direct intraosseous transplantation of DRCC will be applied to patients requiring either solid organ or VCA transplantation as a supportive therapy in order to facilitate the development of a tolerant-inducing microenvironment for the transplant. Additionally, human chimeric cell therapy may have clinical application in the treatment of diseases based on bone marrow transplantation. The chimeric cell therapy will improve engraftment of donor-origin cells and facilitate induction of donor-specific immune non-responsiveness in solid organ and VCA transplantation. The application of established protocol of seven day αβ-TCR/CsA immunosuppression will improve the development of donor-specific mixed chimerism as confirmed in murine models by Siemionow laboratory. This innovative supportive therapy represents breakthrough modality in the field of reconstructive transplantation.

Contributor Information

Maria Z. Siemionow, Email: siemiom@hotmail.com

Maria Z. Siemionow, Email: siemiom@uic.edu.

References

- 1.Schwann T. Mikroskopische Untersuchungen uber die Ubereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachsten der Thiere und Pflanzen. Berlin: Saunderschen Buchhandlung; 1839. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dittmar T, Zanker KS. Cell fusion in health and disease. Volume II: cell fusion in disease. Introduction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;714:1–3. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0782-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen EH, Olson EN. Unveiling the mechanisms of cell-cell fusion. Science. 2005;308(5720):369–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1104799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou X, Platt JL. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of mammalian cell fusion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;713:33–64. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0763-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramakrishnan M, Mathur SR, Mukhopadhyay A. Fusion-derived epithelial cancer cells express hematopoietic markers and contribute to stem cell and migratory phenotype in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(17):5360–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silk AD, et al. Fusion between hematopoietic and epithelial cells in adult human intestine. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barski G, Sorieul S, Cornefert F. “Hybrid” type cells in combined cultures of two different mammalian cell strains. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1961;26:1269–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terada N, et al. Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature. 2002;416(6880):542–5. doi: 10.1038/nature730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ying QL, et al. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002;416(6880):545–8. doi: 10.1038/nature729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dittmar T, et al. Characterization of hybrid cells derived from spontaneous fusion events between breast epithelial cells exhibiting stem-like characteristics and breast cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2011;28(1):75–90. doi: 10.1007/s10585-010-9359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu X, Kang Y. Efficient acquisition of dual metastasis organotropism to bone and lung through stable spontaneous fusion between MDA-MB-231 variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(23):9385–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900108106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256(5517):495–7. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller FR, Mohamed AN, McEachern D. Production of a more aggressive tumor cell variant by spontaneous fusion of two mouse tumor subpopulations. Cancer Res. 1989;49(15):4316–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagler C, et al. Co-cultivation of murine BMDCs with 67NR mouse mammary carcinoma cells give rise to highly drug resistant cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2011;11(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaBarge MA, Blau HM. Biological progression from adult bone marrow to mononucleate muscle stem cell to multinucleate muscle fiber in response to injury. Cell. 2002;111(4):589–601. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarez-Dolado M, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425(6961):968–73. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR, Russell DW. Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature. 2003;422(6934):901–4. doi: 10.1038/nature01539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, et al. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;422(6934):897–901. doi: 10.1038/nature01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weimann JM, et al. Contribution of transplanted bone marrow cells to Purkinje neurons in human adult brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(4):2088–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337659100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nygren JM, et al. Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells generate cardiomyocytes at a low frequency through cell fusion, but not transdifferentiation. Nat Med. 2004;10(5):494–501. doi: 10.1038/nm1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizvi AZ, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells fuse with normal and transformed intestinal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(16):6321–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508593103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson CB, et al. Extensive fusion of haematopoietic cells with Purkinje neurons in response to chronic inflammation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(5):575–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camargo FD, Finegold M, Goodell MA. Hematopoietic myelomonocytic cells are the major source of hepatocyte fusion partners. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(9):1266–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI21301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willenbring H, et al. Myelomonocytic cells are sufficient for therapeutic cell fusion in liver. Nat Med. 2004;10(7):744–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell AE, et al. Fusion between Intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages in a cancer context results in nuclear reprogramming. Cancer Res. 2011;71(4):1497–505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dales S, Siminovitch L. The development of vaccinia virus in Earle’s L strain cells as examined by electron microscopy. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;10:475–503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.10.4.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okada Y, Hosokawa Y. Isolation of a new variant of HVJ showing low cell fusion activity. Biken J. 1961;4:217–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okada Y. Analysis of giant polynuclear cell formation caused by HVJ virus from Ehrlich’s ascites tumor cells. III. Relationship between cell condition and fusion reaction or cell degeneration reaction. Exp Cell Res. 1962;26:119–28. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(62)90207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeheskely-Hayon D, et al. Optically induced cell fusion using bispecific nanoparticles. Small. 2013;9(22):3771–7. doi: 10.1002/smll.201300696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gottesman A, Milazzo J, Lazebnik Y. V-fusion: a convenient, nontoxic method for cell fusion. Biotechniques. 2010;49(4):747–50. doi: 10.2144/000113515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golestani R, Pourfathollah AA, Moazzeni SM. Cephalin as an efficient fusogen in hybridoma technology: can it replace poly ethylene glycol? Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2007;26(5):296–301. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2007.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheong SC, et al. Generation of cell hybrids via a fusogenic cell line. J Gene Med. 2006;8(7):919–28. doi: 10.1002/jgm.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedrazzoli F, et al. Cell fusion in tumor progression: the isolation of cell fusion products by physical methods. Cancer Cell Int. 2011;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-11-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norwood TH, Zeigler CJ, Martin GM. Dimethyl sulfoxide enhances polyethylene glycol-mediated somatic cell fusion. Somatic Cell Genet. 1976;2(3):263–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01538964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurtovenko AA, Anwar J. Modulating the structure and properties of cell membranes: the molecular mechanism of action of dimethyl sulfoxide. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(35):10453–60. doi: 10.1021/jp073113e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo-Parke H, et al. Configuration of electrofusion-derived human insulin-secreting cell line as pseudoislets enhances functionality and therapeutic utility. J Endocrinol. 2012;214(3):257–65. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwaber J, Cohen EP. Human x mouse somatic cell hybrid clone secreting immunoglobulins of both parental types. Nature. 1973;244(5416):444–7. doi: 10.1038/244444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tesarik J, et al. Chemically and mechanically induced membrane fusion: non-activating methods for nuclear transfer in mature human oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(5):1149–54. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.5.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhutani N, et al. Reprogramming towards pluripotency requires AID-dependent DNA demethylation. Nature. 2010;463(7284):1042–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duelli DM, et al. A virus causes cancer by inducing massive chromosomal instability through cell fusion. Curr Biol. 2007;17(5):431–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu X, Kang Y. Cell fusion hypothesis of the cancer stem cell. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;714:129–40. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0782-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blau HM, Blakely BT. Plasticity of cell fate: insights from heterokaryons. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10(3):267–72. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duelli DM, Lazebnik YA. Primary cells suppress oncogene-dependent apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(11):859–62. doi: 10.1038/35041112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malka F, et al. The mitochondria of cultured mammalian cells: I. Analysis by immunofluorescence microscopy, histochemistry, subcellular fractionation, and cell fusion. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;372:3–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-365-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao PN, Johnson RT. Mammalian cell fusion. IV. Regulation of chromosome formation from interphase nuclei by various chemical compounds. J Cell Physiol. 1971;78(2):217–23. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040780208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SU, et al. Effects of chromosomal polyploidy on survival of colon cancer cells. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;57(3):150–7. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2011.57.3.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter MA, Goodfellow PN. Irradiation and fusion gene transfer. Mol Biotechnol. 1995;3(2):117–28. doi: 10.1007/BF02789107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Upender MB, et al. Chromosome transfer induced aneuploidy results in complex dysregulation of the cellular transcriptome in immortalized and cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):6941–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waid TH, et al. Treatment of acute cellular rejection with T10B9.1A-31 or OKT3 in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1992;53(1):80–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kovarik J, et al. Disposition of basiliximab, an interleukin-2 receptor monoclonal antibody, in recipients of mismatched cadaver renal allografts. Transplantation. 1997;64(12):1701–5. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koido S, et al. Regulation of tumor immunity by tumor/dendritic cell fusions. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:516768. doi: 10.1155/2010/516768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weise JB, et al. A dendritic cell based hybrid cell vaccine generated by electrofusion for immunotherapy strategies in HNSCC. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31(2):149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanamoto A, Maki T. Chimeric donor cells play an active role in both induction and maintenance phases of transplantation tolerance induced by mixed chimerism. J Immunol. 2004;172(3):1444–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siemionow M, et al. Development and maintenance of donor-specific chimerism in semi-allogenic and fully major histocompatibility complex mismatched facial allograft transplants. Transplantation. 2005;79(5):558–67. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000152799.16035.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ayala R, et al. Long-term follow-up of donor chimerism and tolerance after human liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(6):581–91. doi: 10.1002/lt.21736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muramatsu K, Kuriyama R, Taguchi T. Intragraft chimerism following composite tissue allograft. J Surg Res. 2009;157(1):129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahhal DN, et al. Dissociation between peripheral blood chimerism and tolerance to hindlimb composite tissue transplants: preferential localization of chimerism in donor bone. Transplantation. 2009;88(6):773–81. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b47cfa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bonde S, et al. Cell fusion of bone marrow cells and somatic cell reprogramming by embryonic stem cells. FASEB J. 2010;24(2):364–73. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cwykiel J, Klimczak A. Therapeutic Potential of Ex-vivo Fused Chimeric Cells in Prolonging Vascularized Skin Allograft Survival. PRS. 2011; 127:26.

- 60.Li LH, et al. Electrofusion between heterogeneous-sized mammalian cells in a pellet: potential applications in drug delivery and hybridoma formation. Biophys J. 1996;71(1):479–86. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79249-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chow T, et al. The transfer of host MHC class I protein protects donor cells from NK cell and macrophage-mediated rejection during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and engraftment in mice. Stem Cells. 2013;31(10):2242–52. doi: 10.1002/stem.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lentz BR. PEG as a tool to gain insight into membrane fusion. Eur Biophys J. 2007;36(4–5):315–26. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lentz BR. Polymer-induced membrane fusion: potential mechanism and relation to cell fusion events. Chem Phys Lipids. 1994;73(1–2):91–106. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(94)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]