Abstract

The cytokine family of interferons (IFNs) has multiple functions, including antiviral, antitumor, and immunomodulatory effects and regulation of cell differentiation. The multiple functions of the IFN system are thought to be an innate defense against microbes and foreign substances. The IFN system consists first of cells that produce IFNs in response to viral infection or other foreign stimuli and second of cells that establish the antiviral state in response to IFNs. This process of innate immunity involves multiple signaling mechanisms and activation of various host genes. Viruses have evolved to develop mechanisms that circumvent this system. IFNs have also been used clinically in the treatment of viral diseases. Improved treatments will be possible with better understanding of the IFN system and its interactions with viral factors. In addition, IFNs have direct and indirect effects on tumor cell proliferation, effector leukocytes and on apoptosis and have been used in the treatment of some cancers. Improved knowledge of how IFNs affect tumors and the mechanisms that lead to a lack of response to IFNs would help the development of better IFN treatments for malignancies.

Key Words: Antibacterial mechanisms, anti-tumor mechanisms, antiviral mechanisms, apoptosis, biological mechanisms, circulating interferon, clinical application, cytokines, effector proteins, evasive mechanisms, immunomodulation, interferon, medical indications, receptors, response genes, signaling mechanisms

Introduction

Almost 50 yr ago, interferons (IFNs) were discovered to be a natural defense system in the human body because of their antiviral activity (1). This family of cytokines functions to regulate antiviral, anti-tumor, and immune responses and cell differentiation (2–11). The IFN system consists of cells that produce and secrete IFNs as a response to viral infection or other foreign stimuli and cells that respond to IFNs by creating an antiviral state. An overview of the IFN system at the cellular level is diagrammed in Fig. 1. Foreign nucleic acids, antigens, and also mitogens newly induce host cell proteins designated as the interferons. Secreted interferon binds to cells and induces them to produce effector proteins that block various stages of viral replication. IFN also (1) inhibits multiplication of some normal and tumor cells, bacteria, and some intracellular parasites, such as rickettsiae and protozoa; (2) modulates the immune response; and (3) affects cell differentiation.

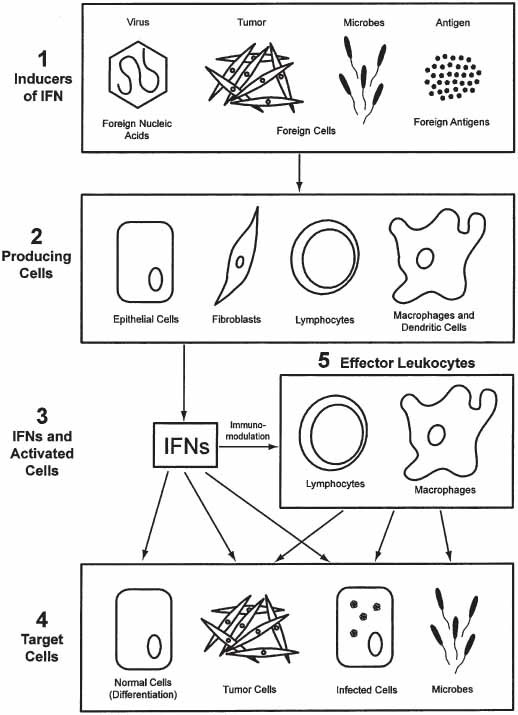

Fig. 1.

Overview of the cellular events in the induction, production, and action of IFN foreign substances (1) induce a variety of cell types; (2) to produce and secrete IFN (3). The secreted IFN (α, β, or γ) acts directly on target cells (4) and also acts indirectly against target cells by activating effector lymphocytes or macrophages (5).

There are two main types of interferon: α- and β-interferons classified as type I and γ-interferon classified as type II (Table 1). α-Interferon mainly is produced by certain leukocytes (dendritic cells and macrophages), β-Interferon by epithelial cells and fibroblasts, and γ-interferon by T- and natural killer cells. An overview of the IFN system at a more molecular level is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Induction of IFN-α , -β , and -γ by Foreign Cells, Foreign Nucleic Acids, and Foreign Antigens

| Inducer | IFN-producing cell | IFN produced |

|---|---|---|

| Foreign cells | Dendritic cells | α |

| Eukaryotic, xenogenic, tumor, virusinfected, prokaryotic. | Macrophages | |

| Foreign nucleic acids | ||

| Viral | Epithelial cells | β |

| Other | Fibroblasts | |

| Foreign antigens and mitogens | T lymphocytes (sensitized) NK lymphocytes | γ |

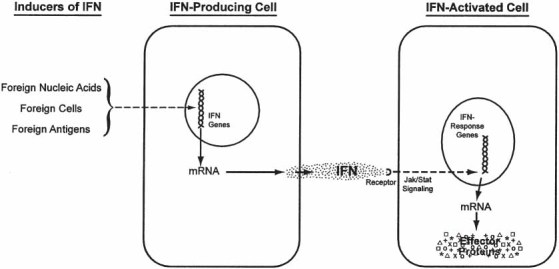

Fig. 2.

Overview of the molecular events in the induction, production, and action of IFN. Inducers of IFN react with cells to newly induce the messenger RNA (mRNA) for interferon, which is translated into the interferon protein, which is then secreted extracellularly. The extracellular interferon binds to the IFN receptors on the membrane of surrounding (or the producing) cells to initiate a JAK/STAT signaling cascade. Those signals activate the IFN-response genes to produce mRNA for the IFN-effector proteins. The effector proteins mediate the antiviral, anti-tumor, immunomodulatory, and all differentiation effects of the IFN system as described in the text.

Viruses have established different mechanisms to circumvent these host responses (12). Some of the many signaling mechanisms and host genes activated by viral infection and the adaptations that viruses use to defend against the IFN response have been characterized in molecular biology studies. IFNs also have been studied clinically and were the first cytokines to be used in clinical therapy, including the treatment of viral infections and malignancies (Table 2 [13]).

Table 2.

FDA-Approved Uses of Interferons

| Interferon α-2α (Roferon®) |

| Hairy cell leukemia |

| AIDS-related KS |

| Chronic hepatitis C a |

| Chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-positive CML patients with CML |

| Who are minimally pretreated (within 1 yr) |

| Pegylated IFN-α-2α (PEGASYS®) |

| Chronic hepatitis C a |

| IFN-α-2β |

| Genital warts |

| Chronic hepatitis B |

| Chronic hepatitis C a |

| Hairy cell leukemia |

| AIDS-related KS |

| Adjuvant therapy for malignant melanoma |

| In combination with chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (follicular |

| Lymphoma) |

| Pegylated IFN-α-2β (PEG-Intron®) |

| Chronic hepatitis C a |

| IFN-α-n3 (Alferon®) |

| Condylomata acuminata |

| IFN-alfacon-1 (Infergen®) |

| Chronic hepatitis C |

| IFN-β-1α(Avonex®, Rebif®) |

| Relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis |

| IFN-β-1β(Betaseron®) |

| Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis |

| IFN-γ(Actimmune®) |

| Chronic granulomatous disease |

| Malignant osteopetrosis |

| aIn the treatment of chronic hepatitis C, unpegylated and pegylated IFN-α-2α and α-2β are given in combination with oral ribavirin except if ribavirin is contraindicated |

IFN As a Natural Defense Against Viruses

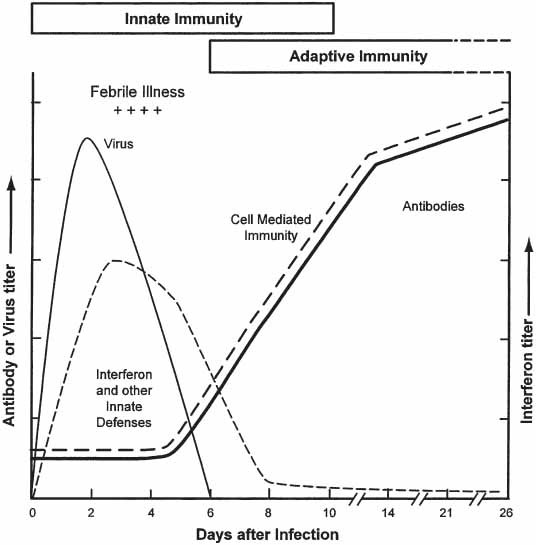

The important role played by IFN as a defense mechanism against viruses is supported by three types of findings: (1) for many viral infections, a strong correlation has been established between IFN production and natural recovery; (2) inhibition of IFN production or action enhances the severity of infection; and (3) treatment with IFN protects against infection. In addition, the IFN system is one of the initial mechanisms of the known host defenses, becoming operative within hours of infection. Figure 3 compares the early production of IFN and innate immunity with the later production of antibody and adaptive immunity during experimental infection of humans with influenza virus. IFN and its inducers also play an important role in protection against many viruses, including hepatitis B and C viruses, poxvirus, coronaviruses, papovaviruses, rhinoviruses, and herpes simplex virus.

Fig. 3.

The roles of innate and adaptive immunity during acute influenza virus infection of humans. During virus infection, the earliest defenses are innate. They include interferon, anatomic barriers, nonspecific inhibitors, phagocytosis, fever, and inflammation. The innate defenses begin within hours and continue until virus is eliminated. The adaptive defenses are specific antibody and cell-mediated immunity. They begin within 5 to 7 d of infection and persist for months after virus is eliminated. Virus levels initially increase rapidly, begin to decline in the presence of the innate defenses, and virus is eliminated after the development of the adaptive defenses. Adapted from ref. 4.

Host Antiviral Response

IFNs act as one of the first lines of defense against viral infection by creating an intracellular milieu that restricts viral replication and alerts the adaptive branch of the immune system to the presence of a viral pathogen. After virus infection, early events in the interferon production response (overviewed in Fig. 2) include the posttranslational activation by phosphorylation of inactive transcription factor families, including nuclear factor (NF)-κB, ATF-2/c-Jun, and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), which activate immediate early genes, like genes that encode type I IFNs IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ (14). IFNs tend to be species-specific in their activation of cells. This process occurs with the activation of multiple signal transduction cascades like the NF-κB/inhibitory factor κB (IκB) kinase complex and stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, which converge in the nucleus to turn on a variety of immunoregulatory genes and proteins that together establish the antiviral state. Specifically, after IFN-α and IFN-β are transcribed and translated, they activate gene expression in adjacent cells by binding to cell surface IFN receptors (Fig. 1), which trigger activation of the Janus kinase (Jak)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathways (15). This allows heterodimers of STAT-1/2 to combine with IRF-9 to create IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) factor (ISGF)-3, which binds to IFN-stimulated response elements (ISREs), which are found in different IFN-induced antiviral genes (15), including IRF-7, which adds to the amplification of the transcriptional response by starting a second wave of IFN gene expression, including other IFN-α genes that were not induced during the early events after viral infection (16,17). The IRF, STAT, and NF-κB transcription factors then translocate to the nucleus and work together to activate a network of antiviral genes like double-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA)-activated protein kinase (PKR), 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthase, and the Mx proteins, which interfere with viral transcription and translation (5,15).

The type II IFN, IFN-γ, acts similarly to the type I IFNs to stimulate the Jak/ STAT-signaling pathways. The activated STAT-1 homodimers translocate to the nucleus to bind the IFN-γ activated sequence family of enhancers, which induces genes, including IRF-1 and IFP-53.

Viral Evasion of the IFN System

Viruses have developed mechanisms to defend against the antiviral activities of the IFN system. These mechanisms can occur on different levels, including interference with the signaling pathways initiated by interferons, disturbance of the protein-protein interactions necessary for production of interferons, and disturbance of the function of antiviral proteins (18). During infection, poxviruses and herpesviruses encode IFN receptor homologs, which prevent interferon signaling (15). The products of various viruses, including C protein of paramyxoviruses, large T antigen of murine polyoma virus, and E6 of human papillomavirus (HPV), can inhibit the signaling capacity of the Jak family of tyrosine kinases (15). STAT proteins also can be compromised, for example, through STAT-mediated degradation and inhibition of STAT synthesis by paramyxoviruses (19). Direct inhibition by the E7 protein of HPV and inhibition after herpesviruses infection can affect the actions of IRF-9 (12).

An IκBα inhibitor encoded by the African swine fever virus can block NF-κB, and after infection with this virus, the NF-κB p65 subunit also can be downregulated (20). An RNA-binding protein, the NS1 protein of influenza A, can inhibit virus-induced and double-stranded RNA-induced NF-κB and IRF-3 actions (21). Adenoviruses, herpesviruses, and retroviruses can inhibit PKR activity through small viral RNA products that bind to PKR but can not activate its serine kinase activity (22). Us11, an RNA-binding protein that is encoded by herpes simplex virus-1, can bind intracellular double-stranded RNA and directly inhibit activation of PKR (23). MC159L, a protein encoded by molluscum contagiosum virus, can inhibit PKR-induced activation of NF-κB (24).

IFN-α has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the therapy of chronic hepatitis B and C, Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), and condyloma acuminatum, but other HPV-associated diseases have been treated using IFN, with inconsistent results (25). In theory, treatment with IFNs should eliminate visible HPV lesions and the virus itself. Some studies have shown that type I IFN-α is less effective than type I IFN-β in treating HPV infection, perhaps related to the higher diffusibility of IFN-α. Compared with type I IFNs, type II IFN-γ is more effective (26). The differences in response may be explained by several factors, including varied levels of expression of HPV oncogenes, interactions between viral proteins and cellular factors that influence viral and host gene expression and function, and mutations found in infected cells that may decrease the IFN response. Proteins of high-risk but not low-risk HPV, like HPV-16 E6, can bind to IRF-3 to inactivate its transactivating function and can inhibit the expression of IFN-inducible genes by the decreasing IFN-β gene expression (27). Also, the expression of high-risk HPV-18 E6 inhibits the Jak- STAT activation in response to IFN-α (28).

It has been shown that HPV has enhancer elements, such as the HPV-interferon responsive element-1 of HPV 16 that is located in the upstream regulatory region and from which transcription of E6 and E7 genes are initiated, can bind IRF-1 during treatment with IFN-γ and stimulate transcription in a dosedependent and cell type-specific manner; also, mutations in HPV-interferon responsive element-1 decrease its ability to bind IFN-α-induced proteins (29).

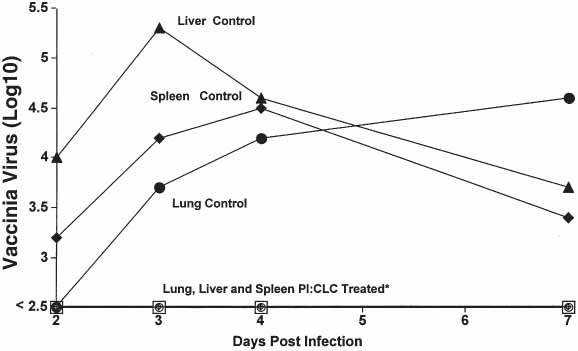

Interestingly, virus evasion in vitro may not always occur in vivo. In vitro poxviruses are relatively resistant to IFNs (Tables 3 and 4). However, in vivo, poxviruses are susceptible to IFNs and their inducers (Fig. 4 [30,31]). Figure 4 shows strong protection of mice against a virulent vaccinia virus infection (31,32).

Table 3.

Comparative Sensitivity to Murine IFN of Vaccinia (Ihd-E) and Vesicular Stomatitis Viruses on Murine L929 Cells

| IFN titer, U/ML | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN | Vaccinia virus | Vs virus | Fold lower vaccinia |

| α standarda | 70 | 1000 | 14 |

| β standarda | 30 | 2000 | 67 |

| γ standarda | 20 | 200 | 10 |

| rα b | 1 × 105 | 3 × 107 | 300 |

| rβb | 1 × 105 | 2 × 107 | 200 |

| α/βc | 20 | 7000 | 350 |

aReference standards from NIH.

bPBL Laboratories.

cCytimmune Laboratories.

Table 4.

Comparative Sensitivity to Human IFN of Vaccinia (IHD-E) and Sindbis Viruses on Human Wish Cells

| IFN titer, U/ML | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN | Vaccinia virus | Sindbis virus | Fold Lower Vaccinia |

| α standarda | <3 | 250 | >83 |

| rα 001b | 630 | 3 × 106 | 5000 |

| rα 012b | 450 | 1 × 106 | 2000 |

| rα 015b | 1000 | 2 × 106 | 2000 |

| rα B2b | <100 | 1 × 104 | >100 |

| rαH2b | 2500 | 3 × 106 | 1000 |

| rα 2ab | 150 | 2 × 106 | 10,000 |

| rα A/Dc | 75 | 2 × 105 | 20003 |

| β standard 1a | <3 | 200 | >67 |

| rβ2 | 125,000 | 5 × 106 | 40 |

| γ standarda | 50 | 325 | 6 |

| rγ-1bd | <3 | 37 | >13 |

aReference standards from NIH.

bPBL Laboratories.

cCytimmune Laboratories.

dActimmune, InterMune Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Fig. 4.

Effect of 100 g of poly I:CLC given intramuscularly on virus multiplication in mouse organs after intraperitoneal infection with vaccinia virus strain Ihd

Clinical Use of IFNs for Viral Diseases

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

IFN α-2b was approved by the FDA for the treatment of chronic HBV infection in 1992, with 5–10 × 106 IU given three times a week for at least 3 mo. The goals of IFN therapy are long-term suppression of HBV replication and viremia, improvement of liver function, and prevention of end-stage liver disease. Because they have an increased risk of progression to chronic active hepatitis and cirrhosis and of hepatocellular carcinoma, patients who test positive for hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) are offered therapy (33,34). The benefits of IFN therapy in those patients who are asymptomatic HBeAg-negative chronic carriers with viral loads less than 105 genomes/mL and normal liver function test values are less clear and under investigation. Markers of effectiveness include the loss of HBeAg with seroconversion to anti-HBe positive status, decrease in viral load, and improvement in liver function tests, and this effectiveness is achieved in 30 to 46% of patients who tolerate IFN therapy (35). Seroconversion usually is correlated to improved histological findings in the liver and is normally maintained long term (36). In patients with cirrhosis, IFN-α treatment also is associated with reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and reduction in mortality from decompensated cirrhosis (37). Loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and undetectable virus load after treatment, or true cure, is observed only in 1 to 5% of patients. However, true cures may increase over time after treatment.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

The current standard of care for HCV infection is combination therapy with a pegylated IFN-α and ribavirin (38). Combination therapy is more effective than monotherapy in all patient groups and especially in patients with characteristics that are associated with low virologic response rates, such as HCV genotype 1 infection, viremia greater than 800,000 IU/mL, increased quasispecies heterogeneity, mutation within the NS5A protein, previous nonresponse to IFN therapy, African-American ethnicity, older age, obesity, and renal impairment (39). The standard measure of favorable response to IFN therapy is sustained virologic response (SVR), or the absence of detectable serum HCV RNA by PCR (<50 IU/mL) 24 wk after completion of therapy, which is correlated with long-term histological improvement and clinical outcome (40). Treatment with pegylated IFN, which has a polyethylene glycol (PEG) moiety covalently bonded to an IFN backbone that increases IFN’s halflife and improves its biological activity, has yielded increased rates of SVR compared with IFN therapy (41). In multicenter, international, randomized, controlled studies of pegylated IFN α-2b and of pegylated IFN α-2a, combination therapy with pegylated IFN and ribavirin for 48 wk increased SVR from 43% to 54–56% (42–44). These trials also showed that those patients with baseline levels of HCV RNA less than 2 × 106 copies/mL or 600,000 IU/mL, with less advanced fibrosis seen on pretreatment biopsy, with body weight of less than 75 kg, and with genotypes 2 and 3 were more likely to achieve SVR. Even though they are less likely to achieve SVR, patients with chronic hepatitis C who are at a higher risk for progression to cirrhosis also are encouraged to receive IFN treatment, including those patients with detectable serum HCV RNA, increased liver function test values, and moderate or greater inflammation of portal fibrosis on liver biopsy (45). The benefit of treatment for patients that do not meet the recommended criteria is less clear and should be considered on an individual basis. Also, patients who currently abuse alcohol or other substances or have severe psychiatric illness or co-morbidities, such as autoimmune or renal disease, are not candidates for IFN therapy (46).

Apoptosis

Apoptosis has multiple significant functions for the cells, such as in cellular differentiation, preventing viral replication by eliminating virus-infected cells, and eradication of cells that undergo uncontrolled cellular proliferation or sustain genetic damage (47). Inhibition of apoptosis can lead to resistance to therapy and malignancy. Advances in molecular genetics have clearly shown that malignant cells usually have defects in cell death control and apoptosis (47).

Direct Apoptotic Effects of Interferons

Apoptotic Effects

Independent of cell cycle arrest, p53, or expression of Bcl2 family members, IFNs can be cytotoxic for some malignant cells. In vitro studies show that the IFN-induced apoptosis is IFN-species specific and dependent on cell histology. IFN-α and IFN-β can stimulate apoptosis in hematopoietic cells, such as chronic myelogenous leukemia and multiple myeloma (48). IFN-β alone stimulated apoptosis in melanoma (49), multiple myeloma (50), and ovarian carcinoma (51). However, for all cell types, stimulation of apoptosis by all IFN subtypes has involved fas- associated death domain (FADD)/caspase-8 signaling, launch of the caspase cascade, release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, interference of mitochondrial potential, changes in plasma membrane symmetry, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragmentation (50). Inhibitors of caspase-3, caspase-8, or dominant negative mutants of FADD in general can prevent IFN-induced cell death (52). IFN-induced apoptosis occurs relatively late (after 48 h of treatment), which suggests the involvement of genes activated by IFNs or intermediate cellular effectors.

Antiproliferative Effects

An acquired defect in one or more proteins that act as check points for normal cell cycle progression often is a requirement for proliferation of cancer cells. Both IFN-α and IFN-β can influence all stages of the cell cycle, typically with a block in G1 or sometimes by lengthening of all phases (G1, G2, and S [53]). IFN-α modulates the retinoblastoma protein (pRb), which is a cell cycle inhibitor by binding to various transcription factors like E2F. In late G1, cyclincdk complexes phosphorylates pRb, and the hyperphosphorylated form releases E2F, which activates genes for DNA replication. Treatment of cells with IFN- α results in inhibition of cell cycle kinases and cyclins such as cyclin D3, cyclin E, cyclin A, and cdc25A. These actions suppress pRb phosphorylation and thus slow progression into S phase (53,54). The additive prolongation of the cell cycle could result in cytostasis, increase in cell size and, eventually, apoptosis (55).

Pro-Apoptotic IFN-Stimulated Genes

IFN also stimulates multiple genes that create a pro-apoptotic environment. Gene microarray studies have found more than 15 presumed IFN-stimulated genes with pro-apoptotic functions, which include caspase-4 and caspase-8, DAP kinases, galectin-9, TRAIL/Apo2L, Fas/CD95, XAF-1, phospholipid scramblase, RIDs, PKR, and 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (55,56). Although none of these IFN-stimulated genes alone are likely sufficient to induce apoptosis, their additive effects with or without other stimuli may result in apoptosis.

Indirect Mechanisms That Promote Apoptosis

Angiogenesis Inhibition

Another mechanism of the anti-tumor effect of IFN is the inhibition of angiogenesis. IFN-α inhibits basic fibroblast growth factor (57). Tumors produce basic fibroblast growth factor and other cytokines to promote local neovascularization. Endothelial cells of tumors show microvascular injury and necrosis after treatment with IFN. In athymic mice, IFN-β-gene therapy using adenoviral IFN-β (Ad-hIFN-β and Ad-mIFN-β) constructs inhibited tumorigenesis and metastasis of a human transitional cell carcinoma cell line (58). Ad-mIFN-β therapy of tumors increased tumor cell apoptosis (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-digoxigenin nick end labeling positivity), heavy infiltration of macrophages, inducible nitric oxide synthase expression, and decreased proliferation marker PCNA. As seen by anti-CD31 immunohistochemistry, tumor-induced angiogenesis microvessel density was significantly reduced within tumors treated with Ad-mIFN-β. Tumors treated with Ad-hIFN-β gene therapy had significant tumor cell and endothelial cell apoptosis, as demonstrated by double staining immunofluorescence (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphatedigoxigenin nick end labeling and CD-31 [58]).

Immunomodulation

IFNs modulate the antibody response, positively or negatively, depending on timing, dose, and type of IFN (59). Protection against antibody-mediated myasthenia gravis in a murine model occurs by downregulation of antibody against the acetylcholine receptor (60) and may be the mechanism by which IFN benefits patients with multiple sclerosis. IFNs also exert antitumor effects by enhancing the functions of cytotoxic T cells, dendritic cells, monocytes (Baron, S., Hernandez, J., and Zoon, K., et al., personal communication, 2004) and natural killer (NK) cells (4,5). In vitro studies demonstrated that IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ stimulated dendritic cells expressing Tumor necrosis factorrelated apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and induced apoptosis of target cells by activation of caspase-3 and NF-κB. Apoptosis of the target tumor cells results in ensuing uptake and processing of apoptotic bodies and presentation of antigenic peptides to CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes. IFNs amplify T-cell and NK-cell cytotoxicity by increasing cell surface expression of TRAIL (61) or Fas ligands and release of perforin from NK cells. IFN-augmented T cells and NK cells have active Fas- and TRAIL-mediated cytotoxic pathways, implying that IFNs also may induce tumor cell apoptosis by activating immune effector cells.

Clinical Uses of IFNs for Malignancies

Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Since the 1980s, multiple reports have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of IFN-α for treatment of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs [62]) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs [63]). The total amount of IFN-α-2b needed to treat a tumor, length of period necessary for the IFNα-2b to stimulate the immune system for cure, and the number of injections required are not fully established. Evidence exists that 1.5 ×106 IU of IFN-2b three times a week for 3 wk is adequate therapy for most BCCs and SCCs; however, larger and more aggressive tumors probably need a higher total and/or individual dose to cure the malignancy (64). IFN-α-2b treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancers often is not used because several arguments have been established against its use as first-line treatment. The cure rates are much less than the cure rates for established surgical modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery. The need for frequent visits and the cost of multiple injections may be more burdensome for the patient than are electrodesiccation and curettage or surgical modalities. The advantages of IFN-α-2b include minimal invasiveness and scarring, and it may be preferable to surgery in patients with systemic disease or poor circulation, those on anti-coagulants, and those with a higher risk of poor wound healing, such as diabetics and the elderly. It may be an important alternative to consider for BCCs and SCCs in which surgery would be deforming or would destroy function and for treatment of positive margins after surgical excision (64).

Imiquimod is an immune response modifier that stimulates monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells to produce IFN-α and other cytokines that are important in stimulating cell-mediated immunity. When applied topically, it is effective against BCCs (although its use is pending approval by the FDA [65]), actinic keratosis (66), Bowen’s disease and SCCs (67), and genital warts (the use of which has been approved by the FDA [68]).

Melanoma

In 1996, the FDA approved high-dose IFN-α-2b for stage IIB-III melanoma as a postsurgical adjuvant therapy. It has become the standard of care and was widely adopted in the medical community. However, the results of both early and subsequent trials have not been clear, and its use in melanoma treatment remains controversial. The low-dose regimen consists of 2 to 3 mU administered two to three times each week for 1 to 3 yr. Early results suggested that there may be some effectiveness with the low-dose regimens (69), but later trials have demonstrated no benefit to survival (70).

The high-dose regimen in the landmark E1684 trial (IFN-α-2b 2.0 × 107 IU IV 5 d/wk for 4 wk followed by a maintenance phase of 1.0 ×107 IU SC 3 d/wk for the rest of the year) showed a clear improvement in survival (71). In four major randomized trials examining a high-dose regimen, all four demonstrated improvement in relapse-free survival, and three of the four demonstrated increases in overall survival (72). The E1684 trial showed the cost-effectiveness of IFN as adjuvant therapy based on both disease-free and overall survival rates. Another reason to consider the use of IFN as postsurgical adjuvant therapy is that no large randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or vaccine therapy has shown an advantage for high-risk melanoma patients (72).

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

With its antiangiogenic and anti-human herpesvirus 8 properties, IFN-α has been used successfully to treat vascular tumors such as AIDS-related KS. Since 1981, IFN has been used in the treatment of HIV-associated KS. Early treatment regimens used doses in the 2.0 × 107 IU/d range, which were associated with significant response rates but also elevated levels of toxicity (73). In later studies, it was found that the response rate was correlated with CD4 count. Patients with CD4 counts greater than 400/mm3 responded, whereas none of those with CD4 counts of less than 150/mm3 had a response (73). Lower dosages of IFN-α combined with zidovudine (i.e., AZT) were found to be effective in treating HIV-associated KS, including those with lower CD4 counts, but with dose-limiting hematological adverse events. However, it was reported that granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor as an adjunct to combination IFN-α/AZT therapy resulted in an increased end-of-study absolute neutrophil count (74).

Other Malignancies

Other cancers such as hairy cell leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and Sezary syndrome, bladder and renal cell carcinomas, follicular lymphoma, and multiple myeloma have all responded to IFNs (55). IFN-α-induced apoptosis of nonadherent hairy cells by increasing the secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and the sensitization of hairy cells to the pro-apoptotic effect of TNF-α. In hairy cell leukemia, IFN-α induces partial responses in most patients but complete responses in only the minority of patients (75). IFN-α is beneficial for those in whom purine analog therapy has failed and those with active infections and are unable to undergo purine nucleoside analog therapy because of the resultant T-cell immunosuppression. IFN-α-2a is administered at a dose of 3.0 × 106 IU SQ QD for 6 mo and then reduced to three times a week for an additional 6 mo. IFN-α-2b is administered at a dose of 2.0 × 106 IU SQ three times a week for 12 mo.

One of the most important advances in the treatment of CML has been IFNs. Complete and partial hematological remission rates after recombinant IFN-α therapy combined with other therapies are reported in approx 70 and 10% of patients, respectively. Recombinant IFN-α-2a or recombinant IFN-α-2b combined with chemotherapy with either cytarabine or hydroxyurea can prolong life in patients with CML (76). Only when combined with cytarabine or hydroxyurea does IFN prolong survival compared with busulfan and hydroxyurea. For all patients treated with recombinant IFN-α, the 5-yr survival is 57% compared with 43% for patients treated with hydroxyurea.

Adverse Events Associated With IFN Treatment

In the treatment of HBV, IFN-α can cause a flare of liver injury, usually just before or during loss of HBeAg. This may be a reflection of the immunomodulatory activity of IFN-α, which can upregulate major histocompatability complex class I antigens on hepatocytes and increase the recognition of HCV infected cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. The flares are inherent to treatment with IFN-α and usually foretell a successful outcome as a marker of increased immune responsiveness to HBV. However, the possibility of IFN-α-induced flares that precipitate liver failure means that IFN-α is contraindicated in advanced cirrhosis. Also, IFN-α may exacerbate cytopenias present in patients with advanced liver disease and splenomegaly. To increase rates of SVR, close adherence to combination therapy with pegylated IFN and ribavirin is essential, which is especially true in patients with HCV genotype 1 and other factors usually associated with low SVR rates (77). In the management of adverse events, it is preferred to adjust doses rather than temporarily interrupt or prematurely discontinue treatment. Patient education about possible adverse events and regular follow-up visits are important to detect side effects early and to encourage compliance to therapy.

Adverse events associated with IFN and ribavirin combination therapy include flu-like symptoms, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and hematological abnormalities. Treatment with pegylated IFN combinations yielded small increases in the rates of mild injection site reactions, dose reductions caused by cytopenias, and influenza-like symptoms when compared with standard IFN combination therapy (43,44). In as many as one third of patients, depression occurs during IFN therapy, and many patients are prescribed therapeutic or prophylactic treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Approximately 80% of patients with HCV infection that experienced depression induced by IFN therapy completed their course of treatment when given paroxetine concomitantly in a prospective trial (78). Hematopoietic growth factors have been used in patients with significant therapy-related cytopenias to prevent dose reductions of IFN and ribavirin and encourage completion of therapy. Patients with HCV who developed ribavirin-induced anemia were given epoetin alpha in a prospective study and were found to have increased hemoglobin levels and were able to maintain ribavirin dosing compared with those who received placebo (79). In another study of patients with HCV who were treated with IFN, those patients who received adjunctive epoetin alpha had improved quality-of-life scores compared with patients who received placebo (80). However, there is no evidence that growth factors improve rates of SVR.

At doses used to treat cutaneous cancers, adverse events of IFNs are dose dependent and are usually mild to moderate. They include flu-like symptoms, such as fever, chills, fatigue, malaise, anorexia, headache, arthralgias, and myalgias. These symptoms diminish with repeated exposure and can be easily controlled with acetaminophen. Some infrequent neurological short-term adverse events include confusion, dizziness, dysarthria, motor weakness, paresthesia, and short-term memory loss. At higher doses, such as those used for treatment of HBV and HCV, depression and transiently elevated liver enzymes, which normalize within 2 to 5 d after therapy, are noted. This treatment modality has dose-related bone marrow suppression, which is reversible upon discontinuation.

In the E1684 trial (high-dose regimen) for adjuvant treatment for melanoma, treatment delays and dosage reductions were required during the study, including half of patients during the induction period and 48% of patients during the maintenance phase (71). Grade 3 toxicities were reported in 67% of all treated patients, whereas 9% had grade 4 toxicities. Adverse events at higher doses include nausea and vomiting, flu-like symptoms, liver function abnormalities, neutropenia, and psychiatric symptoms, including depression.

Conclusions

IFNs are the first line of defense against viruses. However, viruses have evolved mechanisms to evade host surveillance by inhibiting the production and activity of IFNs. The molecular pathways of the IFN system are numerous. The interpretation of the significance of each pathway probably should consider its frequency, magnitude, interactions, occurrence in different cell types, and its effect in vivo. Prophylaxis of viral infections with IFNs generally is more effective than therapy (5). Clinically, many ongoing viral infections and diseases inconsistently respond to IFN therapy and frequently recur after IFN treatment is stopped. However, the development of pegylated IFN for use in HCV infection has improved response rates in that disease. Molecular studies on IFN signaling pathways and viral effects on IFN responses help to elucidate viral pathogenesis and the interactions between the host factors that establish innate immunity. This increased understanding will allow the development of improved antiviral treatments, such as molecules that inhibit the evasive interactions and restore the IFN response.

Despite the beneficial effects of IFNs in some cancers, a substantial percentage of patients still fail to respond. However, the use of IFN-α inducers like imiquimod has increased response rates in the treatment of condyloma acuminatum, SCCs, and BCCs. Improved knowledge of the mechanisms of how IFN affects tumors and the factors that are responsible for a lack of response to IFNs would lead to an improved use of IFN in malignancies, including decreased toxicity with IFN therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rhonda Peake for her excellent editorial assistance and Dr. Ferdinando Dianzani for his insightful review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Isaacs A., Lindenmann J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1957;174:258. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1957.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaacs A. Interferon. In: Smith K. M., Lauffer M. A., editors. Advances in Virus Research. New York: Academic Press, Inc.; 1963. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron S. Mechanism of recovery from viral infection. In: Smith K. M., Lauffer M. A., editors. Advances in Virus Research. New York: Academic Press, Inc.; 1963. pp. 39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dianzani F., Baron S. Nonspecific defenses. In: Baron S., editor. Medical Microbiology. Galveston, TX: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. pp. 1–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron S., Coppenhaver D. H., Dianzani F., et al. Interferon: Principles and Medical Applications. Galveston, TX: The University of Texas Medical Branch; 1992. p. 624. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekisz J., Schmeisser H., Pontzer C., Zoon K. C. Interferons: Alpha, beta, omega, and tau. In: Henry H., Norman A., editors. Encyclopedia of Hormones and Related Cell Regulators. New York: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finter N. B. Interferons. In: Neuberger A., Tatum E. L., editors. Frontiers of Biology. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company; 1966. p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pestka S. The human interferon alpha species and receptors. Biopolymers. 2000;55:254–287. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)55:4<254::AID-BIP1001>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taniguchi T., Takaoka A. A weak signal for strong responses: interferon-α/β revisited. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:378–386. doi: 10.1038/35073080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stark G. R., Kerr I. M., Williams B. R., Silverman R. H., Schreiber R. D. How cells respond to interferon. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron S., Tyring S. K., Fleischmann W. R., Jr., et al. The Interferons. Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. JAMA. 1991;266:1375–1383. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.10.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller D. M., Zhang Y., Rahill B. M., et al. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits IFN-alpha-stimulated antiviral and immunoregulatory responses by blocking multiple levels of IFN-alpha signal transduction. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6107–6113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borden E. C., Lindner D., Dreicer R., Hussein M., Peereboom D. Second-generation interferons for cancer: clinical targets. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2000;10:125–144. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin R., Heylbroeck C., Pitha P. M., Hiscott J. Virus-dependent phosphorylation of the IRF-3 transcription factor regulates nuclear translocation, transactivation potential, and proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 1998;18:2986–2996. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuel C. E. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato M., Suemori H., Hata N., et al. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity. 2000;13:539–548. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes T. K., Baron S. A large component of the antiviral activity of mouse interferon-gamma may be due to its induction of interferon-alpha. J. Biol. Regul. Homeostatic Agents. 1987;1:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan W., Krug R. M. Influenza B virus NS1 protein inhibits conjugation of the interferon (IFN)-induced ubiquitin-like ISG15 protein. EMBO J. 2001;20:362–371. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcin D., Curran J., Itoh M., Kolakofsky D. Longer and shorter forms of Sendai virus C proteins play different roles in modulating the cellular antiviral response. J. Virol. 2001;75:6800–6807. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6800-6807.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiscott J., Kwon J., Genin P. Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;197:143–151. doi: 10.1172/JCI11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X., Li M., Zheng H.,., et al. Influenza A virus NS1 protein prevents activation of NF-kappaB and induction of alpha/beta interferon. J. Virol. 2000;74:11566–11573. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.24.11566-11573.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sen G. C. Viruses and interferons. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poppers J., Mulvey M., Khoo D., Mohr I. Inhibition of PKR activation by the proline-rich RNA binding domain of the herpes simplex virus type 1 Us11 protein. J. Virol. 2000;74:11215–11221. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.23.11215-11221.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gil J., Rullas J., Alcami J., Esteban M. MC159L protein from the poxvirus molluscum contagiousum virus inhibits NF-kappaB activation and apoptosis induced by PKR. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:3027–3034. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim K. Y., Blatt L., Taylor M. W. The effects of interferon on the expression of human papillomavirus oncogenes. J. Gen. Virol. 2000;81(Part 3):695–700. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-3-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koromilas A. E., Li S., Matlashewski G. Control of interferon signaling in human papillomavirus infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:157–170. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(00)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronco L. V., Karpova A. Y., Vidal M., Howley P. M. Human papillomavirus 16 E6 oncoprotein binds to interferon regulatory factor-3 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2061–2072. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S., Labrecque S., Gauzzi M. C., et al. The human papilloma virus (HPV)-18 E6 oncoprotein physically associates with Tyk2 and impairs Jak-STAT activation by interferon-alpha. Oncogene. 1999;18:5727–5737. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arany I., Grattendick K. J., Whitehead W. E., Ember I. A., Tyring S. K. A functional interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1)-binding site in the upstream regulatory region (URR) of human papillomavirus type 16. Virology. 2003;310:280–286. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron S., Salazar A., Pestka S., Poast J. Smallpox: prevention by IFN and an IFN inducer. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:86. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron S., Salazar A., Pestka S., Poast J., Clark W. Smallpox model: Should IFN or an inducer be given along with vaccination during an epidemic? In: Liebert M. A. I., editor. Cytokines, Signaling and Diseases: Annual Meeting of the ISICR in Conjunction With the Society for Cytokines, Inflammation and Leukocytes. Australia: Cairns; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron S., Pan J., Poast J. Frequency of revaccination against smallplox. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003;9:1489–1490. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.020820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liaw Y. F., Tai D. I., Chu C. M., Chen T. J. Development of cirrhosis in patients with chronic type B hepatitis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 1988;8:493–496. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang H. I., Lu S. N., Liaw Y. F., et al. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:168–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong D. K., Cheung A., ORourke K., et al. Effect of alpha-interferon in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993;119:312–323. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niederau C., Heintges T., Lange S., et al. Long-term follow-up of HBeAg-positive patients treated with interferon alfa for chronic hepatitis, B. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334:1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605303342202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lok A. S., Heathcote E. J., Hoofnagle J. H. Management of hepatitis B: 2000—a summary of a workshop. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1828–1853. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Institutes of Health. NIH consensus statement on management of hepatitis C: 2002. NIH Consensus Statements. 2002;19:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hadziyannis S. J., Sette H., Jr., Morgan T. R., et al. Peginterferon-[alpha]2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C. A randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lau D. T., Kleiner D. E., Ghany M. G., et al. Ten year follow-up after interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1998;28:1121–1127. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiffman M. L. Pegylated interferons: what role will they play in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C? Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2001;3:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s11894-001-0038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poynard T., Marcellin P., Lee S. S., et al. Randomized trial of interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alfa-2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Interventional Therapy Group. Lancet. 1998;352:1426–1432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manns M. P., McHutchinson J. G., Gordon S. C., et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fried M. W., Shiffman M. L., Reddy R., et al. Peg interferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fontaine H., Nalpas B., Poulet B., et al. Hepatitis activity is a key factor in determining the natural history of chronic hepatitis, B. Hum. Pathol. 2001;32:904–909. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.28228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muir A. J., Provenzale D. A descriptive evaluation of eligibility for therapy among veterans with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2002;34:268–271. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raff M. Cell suicide for beginners. Nature. 1998;39:119–122. doi: 10.1038/24055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sangfelt O., Erickson S., Castro J., Heiden T., Einhorn S., Grander D. Induction of apoptosis and inhibition of cell growth are independent responses to interferon-alpha in hematopoietic cell lines. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:343–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chawla-Sarkar M., Leaman D. W., Borden E. C. Preferential induction of apoptosis by interferon (IFN)-β compared with IFN-a2, Correlation with TRAIL/Apo2L induction in melanoma cell lines. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:1821–1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Q., Gong B., Mahmoud-Ahmed A. S., et al. Apo2L/TRAIL and Bcl-2-related proteins regulate type I interferon-induced apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001;98:2183–2192. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.7.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morrison B. H., Bauer J. A., Kalvakolanu D. V., Lindner D. J. Inositol hexakisphosphate kinase 2 mediates growth suppressive and apoptotic effects of interferon-beta in ovarian carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:24965–24970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101161200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balachandran S., Roberts P. C., Kipperman T., et al. Alpha/beta interferons potentiate virus-induced apoptosis through activation of the FADD/Caspase-8 death signaling pathway. J. Virol. 2000;74:1513–1523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.3.1513-1523.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balkwill F., Taylor-Papadinitriou J. Interferon affects both G1 and S+ G2 in cells stimulated from quiescence to growth. Nature. 1978;274:798–800. doi: 10.1038/274798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Subramaniam P. S., Cruz P. E., Hobeika A. C., Johnson H. M. Type I interferon induction of the Cdk-inhibitor p21 WAF1 is accompanied by order G1 arrest, differentiation and apoptosis of the Daudi B-cell line. Oncogene. 1998;16:1885–1890. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chawla-Sarkar M., Lindner D. J., Liu Y. F., et al. Apoptosis and interferons: role of interferon-stimulated genes as mediators of apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:237–249. doi: 10.1023/A:1023668705040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Veer M. J., Holko M., Frevel M., et al. Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays . Leukoc. Biol. 2001;69:912–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Folkman J. Clinical applications of research on angiogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1757–1763. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Izawa J. I., Sweeney P., Perrotte P., et al. Inhibition of tumorigenicity and metastasis of human bladder cancer growing in athymic mice by interferonbeta gene therapy results partially from various antiangiogenic effects including endothelial cell apoptosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8:1258–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson H. M., Baron S. The nature of the suppressive effect of interferon and interferon inducers on the in vitro immune response. Cell Immunol. 1976;25:106–115. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(76)90100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deng C., Goluszko E., Baron S., Wu B., Christadoss P. IFN-alpha therapy is effective in suppressing the clinical experimental myasthenia gravis. J. Immunol. 1996;157:5675–5682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sato K., Hida S., Takayanagi H., et al. Antiviral response by natural killer cells through TRAIL gene induction by IFN-alpha/beta. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;1:3138–3146. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3138::AID-IMMU3138>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greenway H. T., Cornell R. C., Tanner D. J., Peets E., Bordin G. M., Nagi C. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with intralesional interferon. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1986;15:437–443. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edwards L., Berman B., Rapini R. P., et al. Treatment of cutaneous squamous Cell carcinomas by intralesional interferon alfa-2b therapy. Arch. Dermatol. 1992;128:1486–1489. doi: 10.1001/archderm.128.11.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim K. H., Yavel R. M., Gross V. L., Brody N. Intralesional interferon alpha-2b in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma: revisited. Dermatol. Surg. 2004;30:116–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Geisse J., Caro I., Lindholm J., Golitz L., Stampone P., Owens M. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: results from two phase III, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004;50:722–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lebwohl M., Dinehart S., Whiting D., et al. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of actinic keratosis: results from two phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel group, vehicle-controlled trials. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004;50:714–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nouri K., OConnell C., Rivas M. P. Imiquimod for the treatment of Bowen’s disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:669–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carrasco D., vander Straten M., Tyring S. K. Treatment of anogenital warts with imiquimod 5% cream followed by surgical excision of residual lesions. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002;47:S212–S216. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.126579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kokoschka E. M., Trautinger F., Knobler R. M., Pohl-Markl H., Micksche M. Long-term adjuvant therapy of high-risk malignant melanoma with interferon alpha 2b. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1990;95:193S–197S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12875517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rusciani L., Petraglia S., Alotto M., Calvieri S., Vezzoni G. Postsurgical adjuvant therapy for melanoma. Evaluation of a 3-year randomized trial with recombinant interferon-alpha after 3 and 5 years of follow-up. Cancer. 1997;79:2354–2360. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2354::AID-CNCR9>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kirkwood J. M., Strawderman M. H., Ernstoff M. S., Smith T. J., Borden E. C., Blum R. H. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14:7–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sabel M. S., Sondak V. K. Pros and cons of adjuvant interferon in the treatment of melanoma. Oncologist. 2003;8:451–458. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-5-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jonasch E., Haluska F. G. Interferon in oncological practice: review of interferon biology, clinical applications, and toxicities. Oncologist. 2001;6:34–55. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scadden D. T., Bering H. A., Levine J. D., et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor mitigates the neutropenia of combined interferon alfa and zidovudine treatment of acquired immune deficiency syndrome-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1991;9:802–808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.5.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goodman G. R., Bethel K. J., Saven A. Hairy cell leukemia: an update. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2003;10:258–266. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silver R. T. Chronic myeloid leukemia. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2003;17:1159–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8588(03)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McHutchinson J. G., Manns M., Patel K., et al. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061–1069. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kraus M. R., Am S., Faller H., et al. Paroxetine for the treatment of interferon-alfa-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;16:1091–1099. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dieterich D. T., Wasserman R., Brau N., et al. Once-weekly epoetin alfa improves anemia and facilitates maintenance of ribavirin dosing in hepatitis C virus-infected patients receiving ribavirin and interferon alfa. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2491–2499. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Afdhal N. H., Goon B., Smith K., et al. Epoetin-alfa improves and maintains health-related quality of life in anemic HCV-infected patients receiving interferon/ribavirin: HRQL from the Proactive Study. Hepatology. 2003;38(suppl 1):302A–303A. doi: 10.1016/S0270-9139(03)80349-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]