Abstract

Little is known about the presence and effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in Puerto Rico’s waters. Four coastal aquatic systems were investigated using low-density polyethylene passive sampling for PCBs and OCPs in water and its overlying air. The highest total freely dissolved and gaseous concentrations of PCBs were found in Guánica Bay, with 4,000 pg/L and 270 pg/m3, respectively. Five OCPs were detected, mainly in water, with greatest concentrations (pg/L) in Guánica Bay: α-HCH (7,400), p,p’-DDE (390), aldrin (2,000), dieldrin (420), and endrin (77). The compound α-HCH was also measured at elevated water concentrations in Condado Lagoon (5,700 pg/L) and Laguna Grande (2,900 pg/L). Jobos Bay did not show values of concern for these persistence organic pollutants. Levels of PCBs and OCPs in water, particularly in Guánica Bay, exceeded USEPA ambient water quality criteria values representing a human health risk regarding consumption of aquatic organisms.

Keywords: Passive sampling, PCBs, Puerto Rico, Pollution, Pesticides, Caribbean, POPs

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are synthetic chemical substances utilized as pesticides, for industrial purposes, or that originate from industrial/combustion processes (CIDA 2008). Exposure to these pollutants has been associated with various adverse health effects such as increased cancer risk, endocrine disruption, reproductive/developmental disorders, among others (CIDA 2008). POPs are characterized by their high environmental persistence, long-range transport, lipophilicity, and biomagnification capacity. The physico-chemical characteristics of POPs allow their distribution in different environmental compartments. Climate change is expected to change their global distribution, affecting their concentration and potential toxicity (Kallenborn et al. 2012). The 2001 Stockholm Convention on POPs targets the elimination or restriction of these chemicals, and calls for their global monitoring in different environmental compartments (CIDA, 2008).

Passive sampling is a suitable monitoring technique to obtain time-weighted average concentrations of POPs (McDonough et al. 2014). Passive samplers collect target contaminants by diffusion, and they can be made of different synthetic polymer materials (Lohmann 2012). For instance, low-density polyethylene (PE) has been used extensively to monitor POPs (e.g., PCBs, OCPs, PBDEs, PAHs) in air and water (Khairy et al. 2014; McDonough et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2016; McDonough et al. 2018). This polymer has various advantages over bulk sample collection and analysis: simple chemical make-up, low-cost commercial availability, easy handling during the field and laboratory processing (Lohmann 2012; McDonough et al. 2014).

Coastal water pollution studies of POPs are needed in the Caribbean region in order to have a regional scale assessment for better management and protection of these valuable ecosystems (Fernandez et al. 2007). A major public health concern arises when these aquatic systems provide food and sustenance for coastal communities. This study used PE passive sampling to determine the extent of POPs contamination in water and air of four coastal aquatic systems of Puerto Rico.

Materials and Methods

Details on the preparation of PE samplers and spiking with performance reference compounds (PRCs) have been previously described (Khairy and Lohmann 2014; Khairy et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2018). Briefly, sheets of PE (2 mils and 50.8 μm thickness) were cut into 10 × 40 cm strips from commercial plastic drop cloth sheeting (Berry Plastics Corp., Evansville, IN). PE samplers (about 2 g each) were precleaned with organic solvents (e.g., n-hexane), and spiked with PRCs that included 2,5-dibromobiphenyl (PBB 9), 2,2’,5,5’-tetrabromobiphenyl (PBB 52), 2,2’,4,5’,6-pentabromobiphenyl (PBB 103), and octachloronaphthalene (OCN). Samplers were wrapped in precleaned aluminum foil and seal until used.

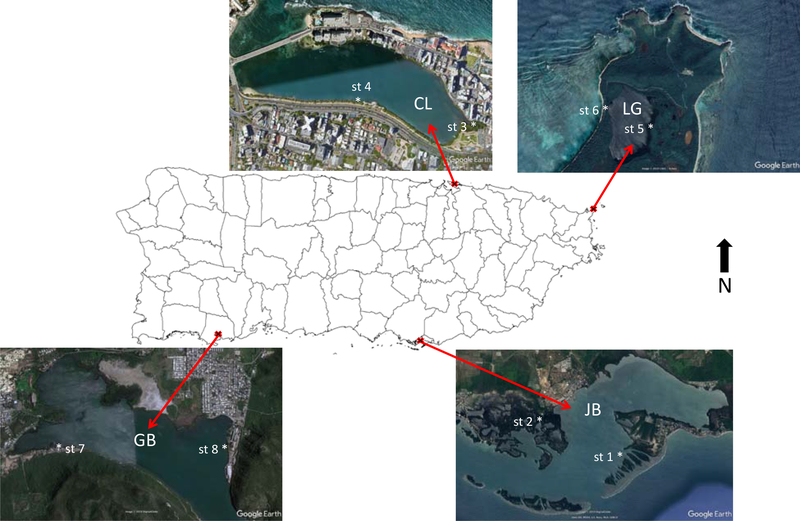

PE passive samplers were deployed for 33 d during May and June of 2018. One sampler at each site was submerged in the water and another suspended in the air in two sampling stations (st) of each of the four aquatic systems selected in Puerto Rico (Lat., 18.324o; Long., −66.327o): Jobos Bay, Condado Lagoon, Laguna Grande, and Guánica Bay (Figure 1). Water samplers were tied to an anchored line 0.3 – 0.6 m below the surface, depending on water depths of sampling stations (0.6 – 1.1 m). Air samplers were secured inside an inverted stainless steel bowl, to provide protection against direct sunlight and rain, and tied to a structure above its corresponding water sampler. In addition, a field blank was included per sampling station to evaluate contamination during sample handling and transport. A demo video of the deployment and retrieval of samplers is provided by the University of Rhode Island (McDonough and Adelman 2013). Collected samplers were transported on ice to the laboratory and stored at −200C until overnight shipment to the University of Rhode Island for analyses.

Fig 1.

PE passive sampling stations (st) for water and air in Jobos Bay (JB), Condado Lagoon (CL), Laguna Grande (LG), and Guánica Bay (GB), Puerto Rico.

In the laboratory, samplers were wiped clean with Kimwipes and extracted overnight in 60 mL n-hexane over anhydrous Na2SO4 and spiked with 10 ng of surrogate labeled PCBs (13C12-PCB 8, 28, 52, 81, 118, 138, 180, 209), hexachlorobenzene (13C12-HCBz), and 13C12-DDT. Sample extracts were concentrated in 200-mL evaporator tubes to < 1 mL using a Turbovap II (Caliper Sciences, Inc, Hopkinton, MA) and transferred to 2-mL amber vials containing 50-μL glass inserts. Only water extracts went through a sample clean-up using solid phase extraction 6-mL/1-g silica tubes (Restek Corp., Bellefonte, PA), eluted with 10 mL of n-hexane, and reconcentrated. All sample extracts received 50 ng of the injection standard 2,4,6-tribromobiphenyl just prior to instrument analysis. Extracted samplers were air-dried, weighed, and this value incorporated in the equation for the calculation of ambient concentrations. Water and air sample extracts in n-hexane were analyzed using an Agilent 6890 GC coupled to a Waters Quattro Micro tandem mass spectrometer. The GC-MS-MS operating conditions are described elsewhere (Khairy and Lohmann 2014). Quantified were 29 PCBs congeners and 25 OCPs (HCBz, α-HCH, β-HCH, γ-HCH, δ-HCH, Heptachlor, Aldrin, Oxychlordane, Heptachlor epoxide, o,p’-DDE, p,p’-DDE, trans-Chlordane, cis-Chlordane, Endosulfane I, trans-Nonachlor, Dieldrin, o,p’-DDD, p,p’-DDD/o,p’-DDT, p,p’-DDT, Endrin, Endosulfane II, Endrin aldehyde, Endosulfane sulfate, Endrin ketone, Methoxychlor). p,p’-DDD and o,p’-DDT could not be separated so the sum is reported here. Quality control included field blanks (n = 8), and laboratory blanks (n = 2). The lowest standard of the calibration curve (8.4 pg/μL) was used as the instrument limit of detection (LOD) (Sacks and Lohmann, 2011). Assuming a final volume of 50 μL, this corresponded to 0.42 ng per PE passive sampler. Only POPs with values equal or above 0.42 ng/PE passive sampler were reported in pg/L and pg/m3 for water and air samples, respectively.

All samplers have PRCs added in order to determine sampling rates, and to correct for lack of equilibrium between target POPs present in water or air, and the sampler as previously explained elsewhere (Booji et al. 2002; Khairy et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2016; McDonough et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2018). Assuming that uptake rate of POPs to PE samplers and elimination of PRCs from PE samplers is the same at equilibrium, POPs concentrations in water and air were calculated using the following equation:

Where, Cwater (air) = concentration in water (pg/L) or air (pg/m3), and CPE = concentration of POPs in the PE sampler (pg/kg), Rs = sampling rate for water (L/d) or air (m3/d), t = deployment time (d), KPE-water (PE-air) = partition coefficient of POPs in PE sampler for water (L/kg) or air (m3/kg), and mPE = PE sampler mass (kg). The RS was estimated by a nonlinear least squares best fit method using Excel Solver by plotting the fraction of each PRCs loss vs its temperature-corrected log KPE-water (PE-air) (Liu et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2018). The equilibrium fraction reached during the field deployment (e.g., 33 d) by each PRC was determined by calculating their fraction loss in field samplers using the amount of PRCs in their corresponding PE field blank sampler (used as initial amount). Concentrations of POPs in water were corrected for salinity and water temperature, while air concentrations were adjusted for air temperature (Lohmann 2012).

Results and Discussion

Average % PRCs loss from water samplers (n = 7) were 100 ± 0% for PBB 9, 59 ± 13% for PBB 52, and 31 ± 9% for PBB 103, while for air samplers (n = 7), PBB 9 also had 100 ± 0% loss, 93 ± 7% for PBB 52, and 29 ± 13% for PBB 103. Sampling rates (Rs) ranged from 37 to 150 L/d for water samplers, while for air samplers Rs values fluctuated from 43 to 190 m3/d. Only PBBs were used to estimate Rs since OCN exhibited large concentration variations in field blank samplers. The average percent recovery of POPs surrogate standards spiked to water and air sample extracts (n = 7 of each) ranged from 30 – 141% and 36 – 189%, respectively. PCBs and OCPs in PE passive samplers were corrected for surrogate standards recoveries. In field and laboratory blanks, individual values of PCBs congeners and OCPs were as high as 1.50 ng/PE, and 3.84 ng/PE, respectively. PCBs and OCPs concentrations in field PE passive samplers were blank-subtracted using levels detected in corresponding field blanks.

Of the 29 PCBs congeners analyzed, at least seven were detected in waters, and five in air, from three of the four aquatic systems included in this study: Guánica Bay, Condado Lagoon, and Laguna Grande (Table 1). Guánica Bay showed the highest and second highest total freely dissolved PCBs concentrations in water, with 4,000 pg/L for st-8 and 740 pg/L for st-7 (Table 1). These values were much higher in comparison to total PCBs concentrations reported for the other three aquatic systems. Guánica Bay’s surrounding areas have been historically used for agricultural production, fertilizers, textile manufactures, among others (Whitall et al. 2014). Recently, sediments of Guánica Bay have been found to contain high levels of PCBs and OCPs with no specific source identified (Whitall et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2016). Station 8 had the highest concentrations of total and individual detected PCB congeners, possibly reflecting differences in PCBs sediment concentrations within the bay. For instance, higher sediment total PCBs concentrations (129 mg/kg) were measured in the east side of Guánica Bay, near st-8, in comparison to other sampling sites (Kumar et al. 2016). Total PCBs levels in sediment in this side of the bay was identified as having the second highest sediment PCBs concentration reported in the USA (Kumar et al. 2016). In air, Guánica Bay st-8 also exhibited the highest concentration of total PCBs, with 270 pg/m3 vs 38 pg/m3 in st-7.

Table 1.

PCBs concentrations in water (pg/L) and air (pg/m3) in three aquatic systemsa.

| Condado Lagoon | Laguna Grande | Guánica Bay | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target analytes | station 3 | station 4 | station 5 | station 7 | station 8 | |||||

| water | air | water | air | water | air | water | air | water | air | |

| PCB-8 | * | * | 4.3 | * | * | * | 79 | * | 430 | 43 |

| PCB-11 | 8.0 | * | 7.1 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-18 | 6.4 | * | 7.4 | * | 2.5 | * | 290 | * | 1400 | 64 |

| PCB-28 | 11 | 13 | 3.4 | * | * | * | 59 | * | 890 | 45 |

| PCB-52 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 1.6 | 7.0 | 0.64 | * | 160 | 27 | 970 | 76 |

| PCB-44 | 1.2 | * | 0.64 | * | * | * | 3.5 | * | 5.2 | 3.6 |

| PCB-66 | * | * | 0.63 | * | 0.48 | * | 2.2 | * | 10 | * |

| PCB-81 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-77 | * | 3.2 | 0.20 | 1.3 | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-101 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 0.81 | 4.1 | 0.55 | * | 34 | 4.4 | 59 | 9.9 |

| PCB-123 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 1.0 |

| PCB-118 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 0.68 | 3.3 | 0.31 | * | 3.4 | 1.0 | 11 | 2.5 |

| PCB-114 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-105 | * | * | 0.13 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-126 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.60 | * | 1.5 | * |

| PCB-153 | 0.86 | 2.2 | 0.56 | 1.6 | 0.59 | * | 46 | 4.8 | 75 | 11 |

| PCB-138 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 0.41 | * | 21 | * | 58 | 7.6 |

| PCB-128 | * | 2.0 | 0.18 | 1.4 | * | * | 1.6 | * | 2.7 | * |

| PCB-167 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-156 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.62 | * | 1.9 | * |

| PCB-157 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-169 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-187 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 18 | 0.99 | 50 | 2.8 |

| PCB-180 | * | * | 0.31 | * | * | * | 18 | * | 38 | * |

| PCB-170 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7.2 | * | 13 | 0.56 |

| PCB-189 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-195 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 1.4 | * |

| PCB-206 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| PCB-209 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Total | 40 | 40 | 29 | 22 | 5.5 | * | 740 | 38 | 4000 | 270 |

Jobos Bay was not included because values in stations 1 and 2 were <LOD

values were <LOD

Condado Lagoon, surrounded by highly urbanized land, was the second most impacted aquatic system by PCBs contamination. Condado Lagoon st-3 exhibited higher total PCBs concentration than st-4 in water (40 pg/L vs 29 pg/L) and air (40 pg/m3 vs 22 pg/m3).

In Laguna Grande, a nature reserve distant from anthropogenic activities, PCBs were only detected in water, with a level of total PCBs considered low (5.5 pg/L). All the 29 PCBs congeners analyzed in this lagoon were below LOD in air (Table 1). Results from only one station (st-5) are presented because samplers for water and air in st-6 were not recovered.

Levels of PCBs in water and air of Jobos Bay were all below LOD (not shown in Table 1). Jobos Bay is the only estuarine reserve within the USA National Reserves located in the Caribbean, and since its designation in 1981, it has undergone significant agricultural, industrial, and residential development at its periphery (Aldarondo et al. 2010). That PCBs were not detected in this aquatic system was unexpected, since PCBs have been previously detected in sediments. For example, in areas closed to Jobos Bay st-2, Aldarondo et al. (2010) and Alegría et al. (2016) reported total PCBs sediment concentrations of 3.74 ng/g dw and 415 ng/g dw. Perhaps PCBs found in sediments or associated with suspended particles in water were not available for accumulation in PE passive samplers because samplers only accumulate freely-dissolved POPs (Sacks and Lohmann 2011). Most common PCB congeners detected among the studied aquatic systems were PCB-52, −101, −118, −153, and −138.

OCPs in water and air of the four aquatic systems were less frequently detected than PCBs, with Guánica Bay being the system with highest levels, especially in water (Table 2). The OCP with the highest concentration in water was α-HCH, detected in three of the studied aquatic systems, with Guánica Bay st-7 showing the highest concentration (7,400 pg/L). Other OCPs detected at higher concentrations in water of Guánica Bay were: p,p’-DDE (48 pg/L for st-8 and 390 pg/L for st-7); and the cyclodiene pesticides aldrin (2,000 pg/L), dieldrin (420 pg/L), and endrin (77 pg/L), which were only detected at st-8. The DDT metabolite o,p’-DDE was only detected at st-7 with 41 pg/L. Previous sediment pollution studies in Guánica Bay confirmed the presence of DDTs (over 80% being DDD and DDE), HCHs, and chlordane with maximum levels for some (e.g., 69.2 ng/g for total DDTs) regarded as an ecological health risk (Whitall et al. 2014). This study did not detect chlordane. Concentrations of DDT-related chemicals (p,p’-DDE and the sum of p,p’-DDD/o,p’-DDT) in water of Jobos Bay, Condado Lagoon, and Laguna Grande were considered low (up to 13 pg/L). For air in all four systems sampled, only DDT-related chemicals were detected, with a maximum value of 12 pg/m3.

Table 2.

Detected OCPs in water (pg/L) and air (pg/m3) in four aquatic systems.

| Jobos Bay | Condado Lagoon | Laguna Grande | Guánica Bay | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target analytes | station 1 | station 2 | station 3 | station 4 | station 5 | station 7 | station 8 | |||||||

| water | air | water | air | water | air | water | air | water | air | water | air | water | air | |

| α-HCH | * | * | * | * | * | * | 5700 | * | 2900 | * | 7400 | * | 2800 | * |

| Aldrin | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 2000 | * |

| o,p’-DDE | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 41 | * | * | * |

| p,p’-DDE | * | * | * | * | 13 | 12 | 6.4 | 9.2 | * | * | 390 | 7.3 | 48 | * |

| Dieldrin | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 420 | * |

| p,p’-DDD/o,p’-DDT | 4.2 | * | * | 1.6 | * | 1.8 | 2.6 | * | * | * | 9.3 | * | 2.9 | * |

| Endrin | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 77 | * |

values were <LOD

Comparing total PCBs and OCPs levels observed in this study to other studies that use the same PE passive sampling technique, total water PCBs concentrations from Guánica Bay (740 and 4,000 pg/L) greatly exceeded the highest levels reported for the Lower Great Lakes: Lake Erie (83.8 pg/L) and Lake Ontario (105 pg/L) (Liu et al. 2016). For air, total PCBs for all four aquatic systems, with a maximum concentration of 270 pg/m3, were below or fell in the range of Lake Erie (19.0 – 421 pg/m3) and Lake Ontario (7.70 – 634 pg/m3) (Liu et al., 2016).

For OCPs, water concentrations were also higher in Guánica Bay in comparison to levels measured in Lakes Erie and Ontario, and in waters of the National Park of Brazil (Itatiaia and Sāo Joaquim) (Khairy et al. 2014; Meire et al. 2016). For instance, aldrin was over 100 times higher than the maximum concentration obtained in Lake Ontario (4.0 pg/L) and Lake Erie (9.0 pg/L) (Khairy et al. 2014). For dieldrin, water concentration in Guánica Bay was 4- to 14-fold higher when compared to the highest concentration detected in Lakes Erie (96 pg/L), Ontario (53 pg/L) and Sāo Joaquim (30.8 pg/L) (Khairy et al. 2014; Meire et al. 2016). The concentration of p,p’-DDE at st-7 (390 pg/L), was above the maximum water concentration of Lakes Erie (99 pg/L) and Ontario (22 pg/L), and waters of the National Park of Brazil (0.24 pg/L) (Khairy et al. 2014; Meire et al. 2016). In terms of α-HCH, only detected in water, its concentration in Guánica Bay, Condado Lagoon and Laguna Grande was 35- and 94-fold greater than the highest level corresponding to Lake Erie with 79 pg/L (Khairy et al. 2014). We did not detect α-HCH in air as it has been reported for the Lower Great Lakes and the National Park of Brazil (Khairy et al. 2014; Meire et al. 2016). Because of its high environmental persistence, this pesticide, found in different isomers, has been detected in air and oceans worldwide (Xie et al. 2011; Menzies et al. 2013). In air, detected levels for p,p’-DDE and the sum of p,p’-DDD/o,p’-DDT were within the concentration ranges measured in the Lower Great Lakes: 0.79 – 37.63 pg/m3, and 0.55 – 5.56 pg/m3, respectively (Khairy et al. 2014).

To evaluate the water quality in all four aquatic systems in this study, concentrations of POPs were compared with the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) human health ambient water quality criteria values for the protection of human health from the consumption of aquatic organisms (USEPA 2018). Levels of total PCBs in both stations of Guánica Bay exceeded 12 to 63 times the USEPA water criteria (64 pg/L) to protect human health from the consumption of aquatic organisms. Also in Guánica Bay, p,p’-DDE (48 and 390 pg/L), dieldrin (420 pg/L), and aldrin (2,000 pg/L) were higher than their water quality criteria of 18 pg/L, 1.2 pg/L, and 0.77 pg/L, respectively. All water concentrations of α-HCH exceeded the water quality criteria of 390 pg/L. Since PE passive samplers accumulate POPs that are freely-dissolved in water, this is the fraction available for bioaccumulation (McDonough et al. 2014). This implies that aquatic organisms (e.g., fish) are at risk of getting high-tissue POPs concentrations. For instance, preliminary results from two fish specimens caught in Guánica Bay showed high tissue total PCB concentrations (1,623 to 3,768 ng/g) (Kumar et al. 2016). Therefore, people that consume aquatic organisms from these aquatic systems, particularly in Guánica Bay, may be at risk of exposure to high concentrations of these persistent organic pollutants. Further studies are needed in Guánica Bay area to evaluate potential health risks posed to humans considering different exposure pathways as recommended by Kumar et al. (2016).

In conclusion, the PE passive sampling method used in this pilot study provided valuable information about the degree of contamination by POPs in water and air of different aquatic systems of Puerto Rico. The high PCBs and OCPs pollution measured by PE passive sampling in Guánica Bay, particularly in water, is an environmental public health concern that corroborated previously reported high sediment concentrations (Whitall et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2016). Results showed that the alarming pollution problem by POPs found in Guánica Bay extends beyond the sediment to the bioavailable water column. To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the use of PE passive samplers to determine POPs concentrations in water and air of coastal aquatic systems of Puerto Rico. Future spatial and temporal trends studies of PCBs, OCPs and other POPs by PE passive sampling are recommended in aquatic systems of Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Caribbean region.

Acknowledgements

This study was the result of a 2018 RCMI Professional Development Award (RCMI Grant # G12 MD 007600). Special thanks go to personnel from the Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, the Conservation Trust of Puerto Rico, and the San Juan Bay Estuary Program for providing their facilities and/or resources for field PE samplers deployment; to Melvin González for providing his property for PE passive samplers installation; to Angélica E. Medina Montañez, Julio A. del Hoyo Mansilla, Grisel Robles, Grace M. Orta, Amanda López, Shaimar N. Cintrón, Guillermo J. Bird, Walter Ramos, and Glenda Almodóvar for field and/or logistics of PE samplers deployment/retrieval; and to Anna Robuck for helping in obtaining the GC-MS data via remote control desktop sharing.

References

- Aldarondo-Torres JX, Samara F, Mansilla-Rivera I, Aga DS, Rodríguez-Sierra CJ (2010) Trace metals, PAHs, and PCBs in sediments from the Jobos Bay area in Puerto Rico. Mar Pollut Bull 60:1350–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria H, Martinez-Colon M, Birgul A, Brooks G, Hanson L, Kurt-Karakus P (2016) Historical sediment record and levels of PCBs in sediments and mangroves of Jobos Bay, Puerto Rico. Sci Total Environ 573: 1003–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booij K, Smedes F, van Weerlee EM (2002) Spiking of performance reference compounds in low density polyethylene and silicone passive water samplers. Chemosphere 46: 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIDA (2008) Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) toolkit. Canadian International Development Agency; http://www.popstoolkit.com/. Accessed April 24 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A, Singh A, Jaffé R (2007) A literature review on trace metals and organic compounds of anthropogenic origin in the Wider Caribbean Region. Mar Pollut Bull 54: 1681–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenborn R, Halsall C, Dellong M, Carlsson P (2012) The influence of climate change on the global distribution and fate processes of anthropogenic persistent organic pollutants. J Environ Monit 14: 2854–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairy MA, Lohmann R (2014) Field calibration of low density polyethylene passive samplers for gaseous POPs. Environ Sci: Processes Impacts 16: 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairy M, Muir D, Teixeira C, Lohmann R (2014) Spatial trends, sources, and air−water exchange of organochlorine pesticides in the Great Lakes Basin using low density polyethylene passive samplers. Environ Sci Technol 48: 9315–9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Ramirez-Ortíz D, Solo-Gabriele HM, Treaster JB, Carrasquillo O, Toborek M, Deo S, Klaus J, Bachas LG, Whitall D, Daunert S, Szapocznik J (2016) Environmental PCBs in Guánica Bay, Puerto Rico: implications for community health. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23: 2003–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang S, McDonough CA, Khairy M, Muir DCG, Helm PA, Lohmann R (2016) Gaseous and freely-dissolved PCBs in the Lower Great Lakes based on passive sampling: Spatial trends and air−water exchange. Environ Sci Technol 50: 4932–4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann R (2012) Critical review of low-density polyethylene’s partitioning and diffusion coefficients for trace organic contaminants and implications for its use as a passive sampler. Environ Sci Technol 46: 606–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough CA, Aldeman D (2013) How to deploy passive samplers: An instructional film for volunteers Great Lakes Passive Sampling - University of Rhode Island; https://web.uri.edu/lohmannlab/welcome/great-lakes-passive-sampling/. Accessed April 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough CA, De Silva AO, Sun C, Cabrerizo A, Adelman D, Soltwedel T, Bauerfeind E, Muir DCG, Lohmann R (2018) Dissolved organophosphate esters and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in remote marine environments: Arctic surface water distributions and net transport through Fram Strait. Environ Sci Technol 52: 6208–6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough CA, Khairy MA, Muir DCG, Lohmann R (2014) Significance of population centers as sources of gaseous and dissolved PAHs in the Lower Great Lakes. Environ Sci Technol 48: 7789–7797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meire RO, Khairy M, Targino AC, Amaral Galvoão PM, Machado Torres JP, Malm O, Lohmann R (2016) Use of passive samplers to detect organochlorine pesticides in air and water at wetland mountain region sites (S-SE Brazil). Chemosphere 144: 2175–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies R, Quinete NS, Gardinali P, Seba D (2013) Baseline occurrence of organochlorine pesticides and other xenobiotics in the marine environment: Caribbean and Pacific collections. Mar Pollut Bull 70: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks VP, Lohmann R (2011) Development and use of polyethylene passive samplers to detect triclosans and alkylphenols in an urban estuary. Environ Sci Technol 45: 2270–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA (2018) National recommended water quality criteria - Human health criteria table. United States Environmental Protection Agency; https://www.epa.gov/wqc/national-recommended-water-quality-criteria-human-health-criteria-table. Accessed April 24 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Whitall D, Mason A, Pait A, Brune L, Fulton M, Wirth E, Vandiver L (2014) Organic and metal contamination in marine surface sediments of Guánica Bay, Puerto Rico. Mar Pollut Bull 80: 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Koch BP, Möller A, Sturm R, Ebinghaus R (2011) Transport and fate of hexachlorocyclohexanes in the oceanic air and surface seawater. Biogeosciences 8: 2621–2633. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Cai M, Adelman D, Khairy M, August P, Lohmann R (2018) Land-use-based sources and trends of dissolved PBDEs and PAHs in an urbanized watershed using passive polyethylene samplers. Environ Pollut 238: 573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]