Abstract

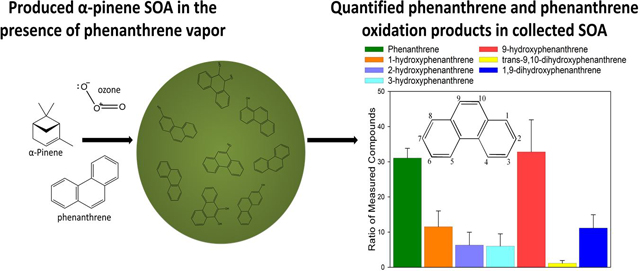

Accurate long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT) modeling of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and PAH oxidation products (PAH-OPs) in secondary organic aerosol (SOA) particles relies on the known chemical composition of the particles. Four PAHs, phenanthrene (PHE), dibenzothiophene (DBT), pyrene (PYR), and benz(a)anthracene (BaA), were studied individually to identify and quantify PAH-OPs produced and incorporated into SOA particles formed by ozonolysis of α-pinene in the presence of PAH vapor. SOA particles were characterized using real-time in-situ instrumentation, HR-ToF-AMS, and collected on quartz fiber filters for offline analysis of PAHs and PAH-OPs. PAH-OPs were measured in all PAH experiments at equal or greater concentrations than the individual PAHs they were produced from. The total mass of PAH and PAH-OPs, relative to the total SOA mass, varied for different experiments on individual parent PAHs: PHE and 6 quantified PHE-OPs (3.0%), DBT and dibenzothiophene sulfone (4.9%), PYR and 3 quantified PYR-OPs (3.1%), and BaA and benz(a)anthracene-7,12-dione (0.26%). Further exposure of PAH-SOA to ozone generally increased the concentration ratio of PAH-OPs to PAH, suggesting longer atmospheric lifetimes for PAH-OPs, relative to PAHs. These data indicate that PAH-OPs are formed during SOA particle formation and growth.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are toxic and ubiquitous environmental pollutants and have been shown to undergo long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT) bound to fine particulate matter (PM2.5)1,2. Several PAHs have been demonstrated to have adverse human health effects, which has led to the global monitoring of 16, primarily parent, unsubstituted PAHs1,3. PAHs are found naturally in crude fossil fuels and are emitted into the environment through anthropogenic extraction, transportation, refinement, and use of these fuels1. Additionally, incomplete combustion of organic material represents the largest source of PAH emissions to the environment4,5. The complex mixture of compounds in natural organic matter results in a wide range of PAH emission profiles when combusted, and the varying chemical and physical properties of PAHs emitted during combustion results in differing degrees of absorption and adsorption to atmospheric PM2.5, defined as particulate matter having an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 microns or less2,6,7.

PM2.5 is a growing public health concern which has been linked to respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological adverse health effects8,9. Human exposure to PM2.5 leads to increases in reactive oxygen species in heart and lung tissue, and has been linked to over 3 million deaths per year around the world8,10 In addition, atmospheric PAH transport has largely been predicted to occur as a result of sorption, or incorporation into, secondary organic aerosol (SOA). SOA, formed from atmospheric reactions of biogenic and/or anthropogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with reactive atmospheric species (such as ozone, hydroxyl radical, and NOx), accounts for an increasing proportion of global PM2.5 mass in the atmosphere (50% - 80%)11,12,13,14,15,16.

The presence of PAHs during SOA formation can significantly affect SOA formation and particle properties, including particle or chemical composition, volatility, and viscosity, leading to their longer atmospheric lifetimes and higher loadings than predicted by models17,18,19. Gas-phase PAHs adsorb on the surfaces of SOA particles during their formation and growth, where they react with gas-phase atmospheric reactants and become entrapped and highly dispersed throughout highly viscous, semi-solid SOA particles18,20. The limited diffusion of the entrapped PAHs shields them from evaporation and oxidation, which enables their LRAT20,21. Since gas-phase ozonolysis of PAHs occurs at a much slower rate than particle sorption, PAH sorption into SOA particles is considered to be the dominant fate of PAHs in the atmosphere11,22. In addition, SOA particles, formed by ozonolysis in the presence of the PAH vapor, contain not only parent PAHs, but also products of surface reactions between PAHs with ozone18,19,23.

Due to their ranges in toxicity, modeling PAH transport in atmospheric PM2.5 is essential for human risk assessment, especially in developing countries10. However, many models assume relatively short PAH atmospheric lifetimes and short volatile and semi-volatile organic compound retention times of VOCs in SOA particles24. This may partially explain under-predictions (30–70%) of PAH atmospheric concentrations as compared to those measured in field campaigns24,13,4. Moreover, current atmospheric models take only a limited number of unsubstituted PAHs into account. These models neglect PAH-OPs that may form during atmospheric transport and are less volatile, and may be more toxic than, their parent PAHs24,13,19,25. Including oxidized compounds, such as PAH-OPs, into the SOA models may more accurately predict the atmospheric lifetimes of PAHs and bring modeled PAH concentrations closer to measured PAH concentrations from field campaigns24. There is currently a lack of data describing the speciation of organic pollutants, such as PAHs, in both laboratory and ambient SOA24,18.

To gain a better understanding of the synergistic relationship between SOA formation and PAH incorporation in SOA, this study was designed to quantify PAHs and PAH-OPs produced during the formation of α-pinene (α-P) SOA through ozonolysis, and in the presence of PAHs. After the cessation of particle formation, these particles were then exposed to additional ozone to assess if further oxidation of PAHs occurs during atmospheric transport. α-P SOA particles were produced in the presence of PAH standards (PAH-SOA), characterized using real-time in-situ instrumentation, a high resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer, collected on quartz fiber filters, and extracted and analyzed for PAHs and PAH-OPs. Phenanthrene (PHE), dibenzothiophene (DBT), pyrene (PYR), and benz(a)anthracene (BaA) were chosen for this study because of their ubiquitous presence in the atmosphere and their range of vapor pressures (2.8 × 10−5 – 2.73 × 10−2 Pa at 25°C) (Table S1)4,5. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show the formation of PAH-OPs in SOA and their subsequent aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

A list of all compounds, abbreviations, chemical characteristics, and manufactures can be found in the supplementary information (Table S1). Analytical standards were used for extraction efficiency testing and the production of calibration curves for quantitative purposes. Standards were stored in the dark at −20°C. To quantify hydroxylated compounds, derivatization was performed using N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N-methyl-trifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA) for mono-hydroxy PAHs, and N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) for poly-hydroxy PAHs, as previously described26. Quartz fiber filters (QFFs) were purchased as 8” x 11” sheets, (G.E. Whatman (Buckinghamshire, UK)), and were cut to fit an inline filter trap. Before use, QFFs were placed in a ventilated oven and held at a temperature over 350°C for 12 hours to remove any organic contaminants and were then sealed in aluminum foil packets and placed inside plastic zip-seal bags.

Experimental Design.

SOA Formation.

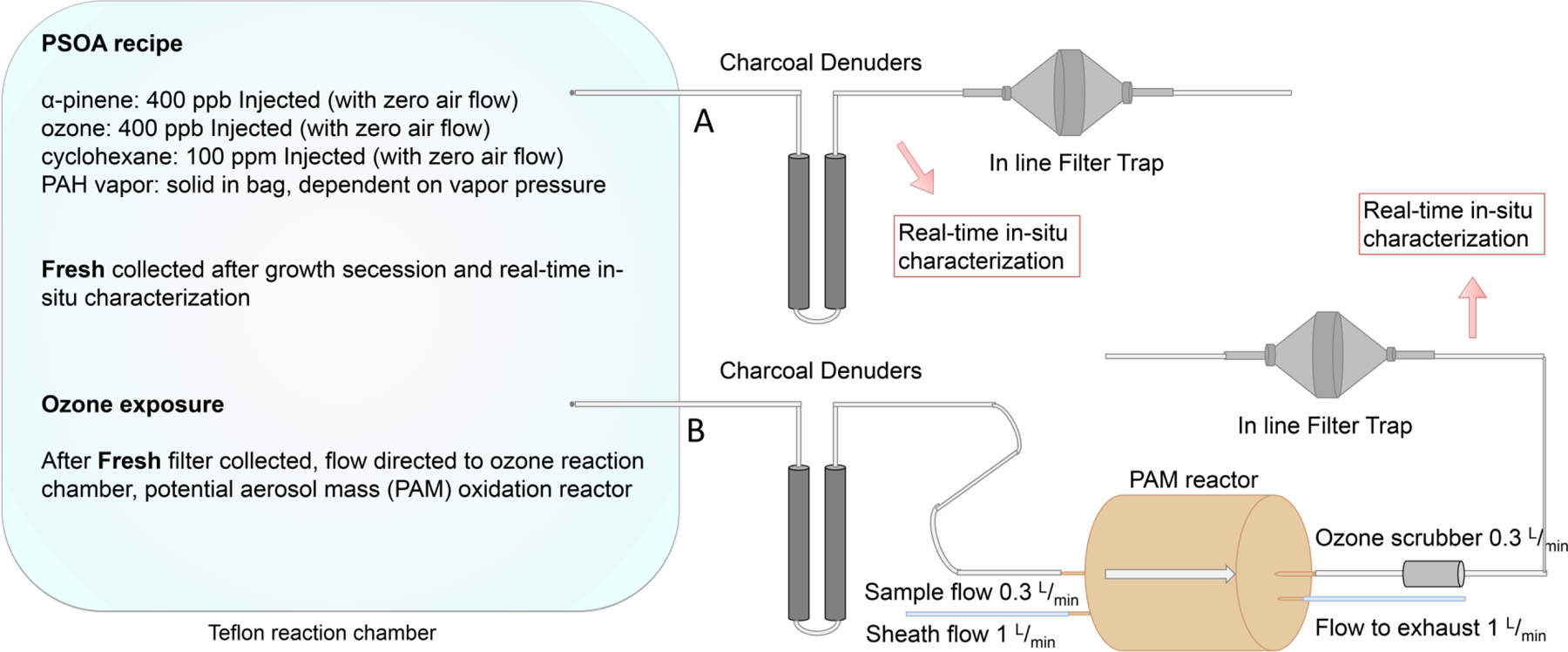

Figure 1 illustrates the generation of PAH-SOA, as previously described17,18. Briefly, to ensure PAH vapor was at or near saturation vapor pressure, in triplicate experiments, ~0.5 g of individual PAH solid was placed into ~70 L Teflon bags filled with zero air and allowed to equilibrate for 48 hours ahead of SOA production. Estimates of PAH vapor phase mixing ratios can be found in the supplemental information (S14-S15). As detailed elsewhere17,18, PAH-SOA formation was initiated by introducing 100 ppm cyclohexane (used as a hydroxyl radical scavenger), 600–800 ppb ozone (produced using Jelight Company (Irving, CA) model 600 ozone generator), and 400 ppb α-P (used as model system for biogenic SOA precursors) into Teflon bags27,28. Ozone was measured using a Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) model 49i Ozone Monitor. The SOA was allowed to grow for ~1 hour. Size distributions and mass loadings of PAH-SOA particles were measured in-situ in real time (RTIS) using a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS), which was comprised of a TSI (Shoreview, MN) Differential Mobility Analyzer (DMA) model 3080 and a TSI ultrafine condensation particle counter (CPC) model 3786, using the documented α-P SOA density of 1.18 g/cm3 as a reference17,29. Particle characteristics, such as vacuum aerodynamic diameter, shape, density, and mass spectra were measured using a single particle mass spectrometer, miniSPLAT, as described in detail elsewhere.17 Additionally, an Aerodyne high resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS) was used to obtain average mass spectra of polydisperse SOA particles30.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup: SOA was produced by injecting 400 ppb α-pinene, 600–800 ppb ozone, and 100 ppm cyclohexane (to act as OH radical scrubber) into a ~100 L Teflon reaction chamber filled with zero air equilibrated with PAH vapor from solids. Particle growth was monitored using SMPS. When particle growth stopped (~ 1 hour), the fresh filter (A) was collected by directing a flow of the sample through charcoal denuders, to remove gas phase organic molecules, and onto a QFF in an inline filter trap, after real-time in-situ particle characterization was performed using single particle mass spectrometer (miniSPLAT). After fresh SOA collection was complete, the sample flow was directed into an oxidation flow tube reactor (PAM), for ozone exposure samples (B), allowed to mix, and again analyzed using miniSPLAT and collected using the inline filter trap.

To assess the volatility of the SOA particles, particles were size-selected with a DMA, passed through two activated charcoal denuders, and loaded into a stainless steel evaporation chamber that contained a layer of activated charcoal as detailed elsewhere27. Particle vacuum aerodynamic diameter was periodically measured as a function of time to quantify particle evaporation kinetics27,31. Triplicate controls of pure α-P SOA were also collected in each experimental setup and analyzed along with each PAH-SOA experiment. No PAH or PAH-OPs were detected in the pure α-P SOA controls (Figure S1). All experiments presented were conducted at low (≤ 5%) relative humidity (RH). Given that previous works have shown that increased RH decreases SOA viscosity and diminishes the ability of SOA to shield PAHs from oxidation24, future studies will include experiments conducted at different RHs.

Fresh PAH-SOA.

After particle growth had ceased in each individual Teflon bag, the total SOA mass loading (μg/m3) was measured for each batch of α-P SOA or PAH-SOA using SMPS. Using Teflon tubing, air from the Teflon bag was pulled through two charcoal denuders (in series), to remove gas-phase organic molecules (including PAHs), and then through a QFF fitted into a 4.7 cm inline filter trap. This was done until at least 15 μg of PAH-SOA (or α-P SOA) mass was collected (based on mass loading calculations). Due to the low vapor pressure of BaA, and preliminary experimental results that showed no BaA concentration above the detection limits in the QFF extracts, ~150 μg of BaA-SOA (from two individual bags) was collected on a single QFF to ensure the BaA concentration were above the detection limit. QFFs were removed from the inline trap, sealed in pre-baked aluminum foil packets, stored at −20°C to reduce volatilization loss, and transported on dry ice, until extraction.

Ozone-exposed PAH-SOA.

In order to test if PAHs and PAH-OPs incorporated in freshly formed highly viscous PAH-SOA particles can undergo heterogeneous oxidation reactions during atmospheric transport, a 13.3 L potential aerosol mass oxidation flow reactor (PAM, an Aerodyne (Billerica, MA)) was used to expose particles to high concentrations (6–10 ppm) of ozone32. Dry zero air was used as the sheath flow at 1 L/min and the sample flow rate was 0.3 L/min (Figure 1). To ensure particles were well-mixed with ozone in the PAM reactor, QFF collection began after the individual PAH-SOA or α-P SOA was flowed through the PAM reactor for 10–15 minutes. The high concentration of ozone in the PAM reactor, and the residence time of ~10 min for particles in the PAM reactor, resulted in a particle exposure to ozone equivalent to that experienced by PM2.5 during LRAT18. The flow from the PAM reactor was passed through a Perma Pure ozone scrubber (Toms River, NJ) to strip away gas phase ozone from the sample stream before QFF collection. An average ~20-fold decrease in mass loading was measured through all experiments after ozone exposure in the PAM reactor. This was primarily due to dilution, wall losses, and evaporation in the PAM reactor and transfer lines.

The PAH-SOA ozone exposure experiments were conducted in triplicate with the activated charcoal denuders before the PAM reactor to remove the gas-phase organic compounds (PAHs, PAH-OPs, α-P, and PAH-SOA). To assess if gas-phase organic compounds changed the measured chemical composition of the PAH-SOA particles, triplicate ozone exposure experiments were performed with and without the charcoal denuders placed in line before the PAM reactor. In addition to QFF collection, particles underwent real-time in-situ characterization in all experiments. Due to variability in particle losses during PAH-SOA exposure in the PAM reactor, and the significantly lower mass of collected particles on the QFF, ozone exposure data had higher uncertainty and higher standard error than fresh SOA data. No statistical difference was measured in the compounds detected between PAH-SOA ozone exposures with or without gas phase organic compounds present (Table S2).

To clean the experimental system between PAH-SOA experiments, nitrogen gas was flushed through the entire system (with PAM reactor lights turned on) until the CPC no longer detected particles. System blanks were collected on QFFs by flowing zero air (2 L/min for 5 to 10 minutes) through the entire experimental system. System blanks were analyzed along with all samples, and no PAHs or PAH-OPs were detected above lab blank concentrations. This indicates that the cleaning procedure removed any lingering PAH-SOA from the experimental system.

QFF extraction.

The QFFs were removed from their cold-stored sealed foil envelopes, and immediately folded in half, tightly rolled and inserted into 4 mL amber glass vials. Isotope labeled surrogate standards (Table S3) were spiked on QFFs and used to account for extraction losses.

Due to the volatility of some parent PAHs and PAH-OPs, many extraction methods resulted in significant analyte loss during solvent evaporation33. To reduce losses, sonication of the QFF was chosen to reduce extraction steps. Dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and acetone were tested for the highest analyte recovery, and while the dichloromethane and ethyl acetate had high recovery for the nonpolar PAHs (~50% for each), acetone provided the highest recovery for the more polar PAH-OPs (~80%) while slightly lower for the PAHs (~43%). Sonication was therein performed with 2 mL acetone solvent for 60 min at room temperature as the QFF extraction method. This procedure did not require solvent evaporation or exchanges, and provided an average of ~68% extraction recovery for spiked analytes (details for efficiency testing are in the SI, and on Table S4).

The extract was transferred into 2 mL amber vials with pre-baked Pasteur pipettes. The QFF extract volume average was between 1000 and 1200 μL. To ensure accurate dilution calculations, all extracts were brought to a final volume of 1500 μL with acetone. Aliquots of the extract were then used for chemical analysis as described in the SI.

To account for any laboratory PAH or PAH-OP contamination, clean lab blank QFF filters were extracted and analyzed alongside experimental QFF. Low concentrations of DBTS, PHE, PYR, BaA and 1,9-OHPHE were measured in lab blank and were subtracted from sample measurements.

Chemical analysis.

Prior to analysis, isotopically labeled internal standards (Table S4) were added to QFF extract aliquots. Identification and quantification was performed using an Agilent J&W 30 m X 0.25 mm i.d. (0.25μm film thickness) DB-5 capillary column on an Agilent 5977A Gas Chromatograph, coupled to a quadrupole Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) operated in 70 Volt electron impact ionization mode. Detailed GC-MS methods can be found in supplementary information (SI). Extracts were analyzed using both selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode, to look for and quantify PAHs and PAH-OPs with available analytical standards, and full scan mode (with and without derivatization) to identify unknown peaks that might be associated with other PAH-OPs without available analytical standards. To measure hydroxy substituted PAHs (OHPAHs), derivatization using MTBSTFA for mono-hydroxylated OHPAHs, and BSTFA for poly-hydroxylated OHPAHs, was performed. This process required incubation at 65°C for 25 minutes (MTBSTFA) or 70°C for 45 minutes (BSTFA) and is described in the SI. Mass spectra of GC-MS fragmentation were interpreted using Mass Hunter software. Lab blank PAH or PAH-OP concentrations were subtracted from their measured concentrations, and divided by the total SOA mass collected, to give the weight percent (wt%) of PAH or PAH-OP. We report the mean weight percent ± one standard error (SE).

Statistical analysis.

For each experiment, PAH-SOA were produced in triplicate reaction chambers and fresh and ozone-exposed QFFs were collected from each reaction chamber experiment for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using R and R-studio software. A two sample Students T-test was used to test for significance, with p-value ≤ 0.05. Due to its low vapor pressure, only one BaA experiment was conducted and no statistical analysis was performed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

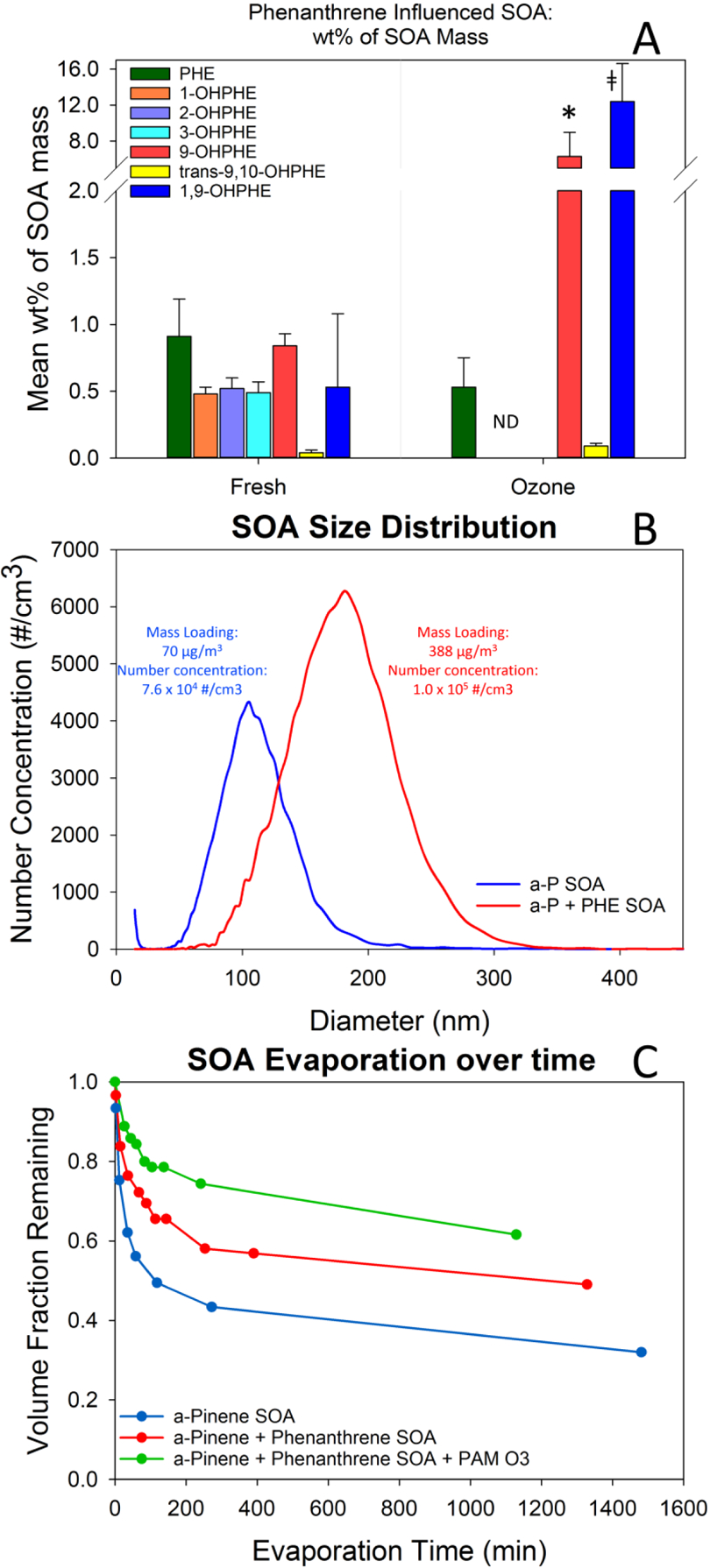

The measurements of PAH and corresponding PAH-OPs for all the experiments in this study are presented in Table 1, Figure 2A, and Figure S2. The results are reported as the mean weight percent (wt%) of PAHs and PAH-OPs relative to the total collected mass of PAH-SOA on the QFF (± one standard error). The PAH-OP concentrations are also reported as a ratio relative to the parent PAH concentration in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measured PAH and PAH-OP in PAH-SOA. Reported values represent the mean wt% of the compound (mass of analyte / mass of PAH-SOA collected) in the PAH-SOA with 1 standard error (± SE) reported. Ratio to Parent PAH was determined by dividing the detected mass of PAH-OP into the detected mass of the Parent PAH. n indicates the number of individual SOA experiments performed in separate reaction chambers using each PAH. ND indicates not detected and N/A indicates not applicable. Subscript numbers are used to show SE that is beyond the significant digit (two decimal places) reporting for these measurements.

| Fresh PAH-SOA | Ozone-exposed PAH-SOA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAH in Teflon | Abbrev. | wt % (± SE) of PAH-SOA | Ratio to Parent PAH (OP/PAH) | wt % (± SE) of PAH-SOA | Ratio to Parent PAH (OP/PAH) |

| Bag Oxidation Product | |||||

| Phenanthrene (n=4) | PHE | 0.91% (0.28) | 0.53% (0.22) | ||

| 1-hydroxyphenanthrene | 1-OHPHE | 0.48% (0.05) | 0.56 | ND | ND |

| 2-hydroxyphenanthrene | 2-OHPHE | 0.52% (0.08) | 0.34 | ND | ND |

| 3-hydroxyphenanthrene | 3-OHPHE | 0.49% (0.08) | 0.33 | ND | ND |

| 4-hydroxyphenanthrene | 4-OHPHE | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 9-hydroxyphenanthrene | 9-OHPHE | 0.84% (0.09) | 0.91 | 6.27% (2.63) | 12.11 |

| cic-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene | cis-9,10-OHPHE | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| trans-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene | trans-9,10-OHPHE | 0.04% (0.02) | 0.02 | 0.09% (0.02) | 0.15 |

| 1,9-dihydroxyphenanthrene | 1,9-OHPHE | 0.53% (0.55) | 0.59 | 12.33% (5.75) | 9.74 |

| phenanthren-1,4-dione | 1,4-PHE-dione | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 9,10-phenanthrequinone | 9,10-PHEQ | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 2’-formyl[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-carboxylate | 2’F(1–1’BP)2C | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Dibenzothiophene (n=3) | DBT | 2.45% (0.61) | 6.86% (1.85) | ||

| Dibenzothiophene sulfone | DBTS | 2.46% (0.76) | 1.01 | 2.29% (0.49) | 0.33 |

| Diphenyl Sulfoxide | DPS | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Pyrene (n=3) | PYR | 1.79% (0.62) | 6.32% (3.42) | ||

| 1-hydroxypyrene | 1-OHPYR | 1.25% (0.31) | 0.70 | 5.91% (2.24) | 0.94 |

| 4H-cyclopenta16phenanthren-4-one | 4H-CPP | 0.07% | 0.01 | ND | ND |

| 6H-benzo(cd)pyrene-6-one | 6H-BcdP | 0.04% (0.02) | 0.02 | 0.70% (0.22) | 0.11 |

| 4-carboxy-5-phenanthrenecarboxylate | 4C5PC | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Benz(a)anthracene (n=1) | BaA | 0.08% | N/A | ||

| 3-hydroxybenz(a)anthracene | 3-OHBaA | ND | ND | ||

| benz(a)anthracene-7,12-dione | 7–12-BaA-dione | 0.19% | 2.5 | ||

Figure 2.

A) Mean wt% (± 1 standard error) of compounds measured in collected freshly formed and ozone-exposed PHE-SOA, measured using GC/MS. * indicates a statistically convincing evidence of a difference (p-value < 0.10) in the measured concentration (wt%) from fresh to ozone-exposed. ‡ indicates a statistically significant difference in measured concentration of PHE-OP than the PHE in ozone exposed PHE-SOA. B) Mobility size distributions of pure α-P SOA particles (blue) and PHE-SOA particles formed by ozonolysis of α-pinene in the presence of gas-phase PHE (red). C) Evaporation kinetics of α-P SOA (blue), PHE-SOA (red), and PHE-SOA exposed to additional ozone (green) measured as the volume fraction of particles remaining over time in minutes, measured with single particle mass spectrometer (miniSPLAT).

Phenanthrene.

PHE, with a vapor pressure of 1.61 × 10−2 Pa, was measured at 0.91% (± 0.28) of the fresh PHE-SOA mass (Figure 2A) and had the largest number of different PAH-OPs identified of all the PAHs tested. A total of six individual PHE-OPs (including 1-,2-,3-,& 9,-OHPHE, trans-9,10-OHPHE, and 1,9-OHPHE) were identified and quantified in the PHE-SOA QFF extracts. The sum of PHE-OP masses measured within the fresh PHE-SOA extracts was 2.75 times the mass of the PHE measured in the same extracts (Table 1). The percent of individual PHE-OPs measured in the fresh PHE-SOA extracts, was: 9-OHPHE 0.84% (± 0.09), 1,9-OHPHE 0.53% (± 0.16), 2-OHPHE 0.52% (± 0.08), 3-OHPHE 0.49% (± 0.08), 1-OHPHE 0.48% (± 0.04), and trans-9,10-OHPHE 0.04% (± 0.02).

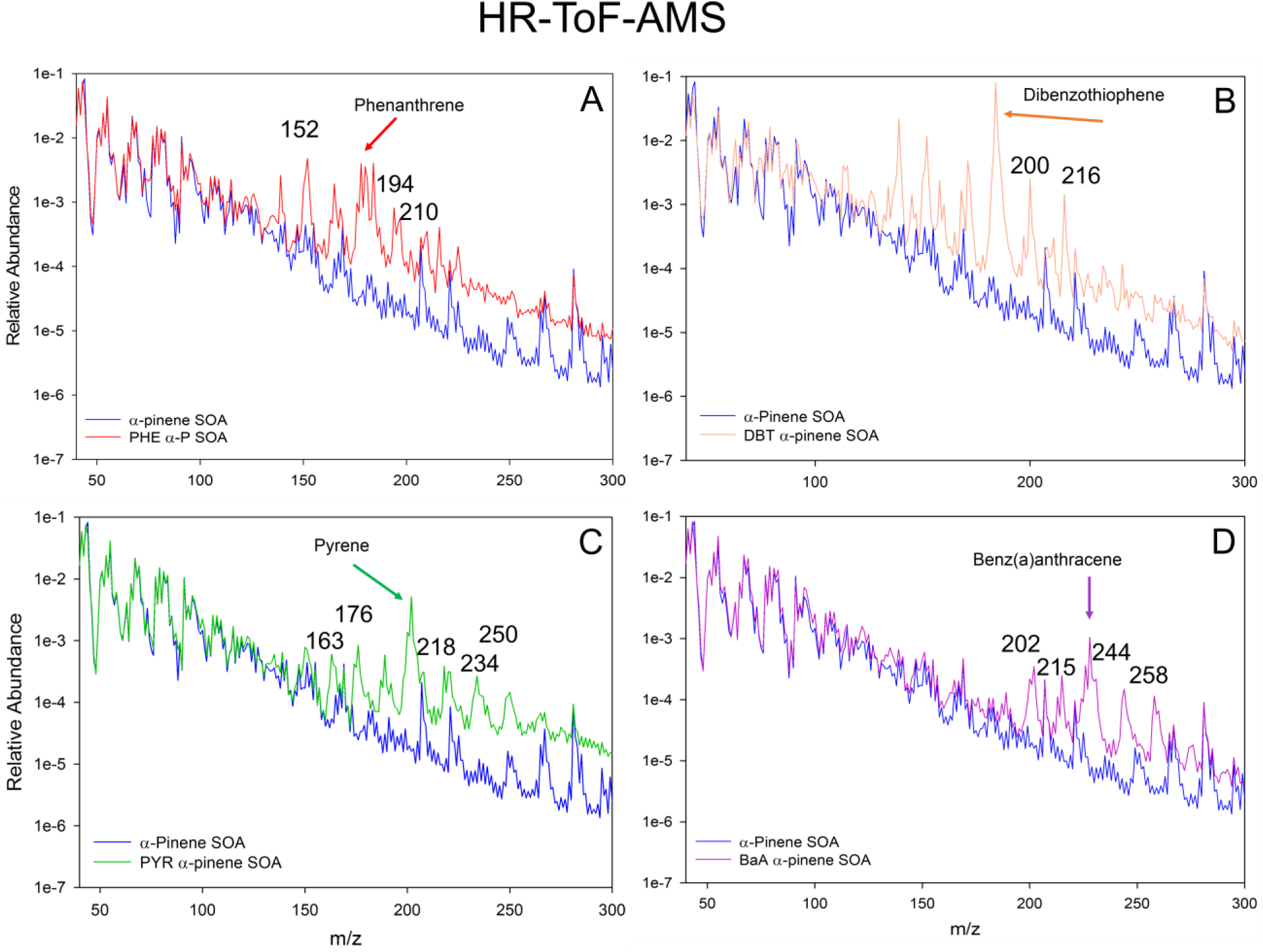

The HR-ToF-AMS mass spectrum of the PHE-SOA particles in Figure 3A shows an increase in the number of higher m/z peaks associated with PHE-SOA particles, relative to SOA particles. This suggests that additional non-volatile compounds (including PHE-OPs) were present in the PHE-SOA particles than were detected by GC/MS (with and without derivatization). These additional non-volatile compounds may include long-lived reactive oxygen intermediates (ROIs), which can play an important role in heterogeneous ozonolysis of PAHs34,31. It has been suggested that the weakly bound physio-sorbed O3 molecules can undergo dissociation to form molecular oxygen and a ROI, such as chemisorbed O atom bound to the delocalized π-electrons of PAH aromatic surfaces34. These long-lived ROIs may then form PAH-OPs or react with other chemical species, including those formed during oxidation of α–P SOA precursor. The surface interactions of long-lived ROIs were suggested to lead to the formation of oligomers, with high molecular weight and low vapor pressure, which can lead to the nucleation and growth of new particles35.

Figure 3.

HR-ToF-AMS data for the four PAHs tested in this study. Each plot shows the relative abundance of the peaks plotted in log scale as a function of the m/z measured. Each plot has α-pinene SOA (blue) with the PAH tested; A = phenanthrene, B = dibenzothiophene, C = pyrene, D = benz(a)anthracene. Each plot has an arrow pointing to the experimental PAH peak, and m/z peaks which may be associated with PAH-OPs based on previous works36,44,45.

The potential effects of PHE vapor on the formation of SOA particles were measured using real-time in-situ characterization18. SMPS measurements showed an increase in mean particle size, as well as number concentrations of SOA particles, leading to a larger SOA mass forming when PHE vapor was present (Figure 2B). The presence of PHE vapor in the Teflon bag increased the SOA mass loading by ~450%, compared to pure α-P SOA created under the same conditions. This increase in SOA particle mass loading cannot be explained by the small fraction of PHE and PHE-OP mass present in the particles (~2%). This suggests that while the presence of PHE enhances SOA formation, it is not the cause of the increase in mass loading. A comparison of the normalized mass spectra of pure α-P-SOA and PHE-SOA, with significantly higher mass loadings, points to their similarities at lower m/z (Figure 3A & S3A), indicating that the additional PHE-SOA mass is dominated by α-P oxidation products. A similar trend is observed for all other PAHs used in the present study and for other PAHs and SOA precursors.18 Given the surprisingly large magnitude of the effect of PAHs on SOA formation, it requires further understanding of the processes involved, which is a focus of ongoing and future studies.

The measured PHE concentration after PHE-SOA ozone exposure appeared to change from the fresh PHE-SOA concentration (from 0.91% (± 0.28) to 0.53% (± 0.22) of the total PHE-SOA mass), but was not statistically significantly different (Figure 2A). The sum of PHE-OP masses measured within the ozone-exposed PHE-SOA extracts was approximately 12 times the mass of the PHE measured in the same extracts (Table 1). After PHE-SOA exposure to ozone, the 1-, 2-, and 3-OHPHEs concentrations were below the detection limit. The 9-OHPHE (6.27% (± 2.63)), trans-9,10-OHPHE (0.09% (± 0.02)), and 1,9-OHPHE (12.33% (± 5.75)) concentrations increased from fresh PHE-SOA to the ozone-exposed PHE-SOA (Table 1). As mentioned above, given the variability in particle losses during sample exposure in the PAM reactor and significantly lower mass of the collected samples, the absolute values of PHE and PHE-OPs concentrations after ozone exposure present higher uncertainty, compared to fresh PHE-SOA. The data suggest that, during transports through the PAM reactor, PHE-SOA particles underwent additional heterogeneous reactions with ozone and/or evaporation of more volatile PHE-SOA components occurred. Whichever occurred, the processes resulted in slower particle evaporation kinetics (Figure 2C). The retention of PHE and PHE-OPs in PHE-SOA particles exposed to high ozone concentrations suggests that, while some of the volatile components in the PHE-SOA particles were evaporated during high ozone concentration exposure, the less volatile OPs remained in the particles.

Ozonolysis of aromatic compounds can lead to different substitutions on the PAH rings36,34. Thermodynamic calculations suggest that an OH adduction is favorable over carbonyl adductions due to the highly instable epoxide intermediates, both resulting in low-volatility products37. PHE ozonolysis has previously been measured to form 2’-formyl[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-carboxylate (2’F(1–1’BP)2C) in laboratory studies of PHE bound to the surface of silica particles22. However, this compound was not detected in the QFF extracts of PHE-SOA. In addition, non-targeted screening of the PHE-SOA extracts, using electron impact ionization in full scan mode (with and without derivatization), showed the same three unidentified chromatographic peaks in both PHE-SOA and α-P SOA QFF extracts (Figure S1), suggesting that additional peaks observed in the HR-ToF-AMS mass spectra (Figure 3a) were non-volatile compounds.

Dibenzothiophene.

DBT has the highest vapor pressure (2.73 × 10−2 Pa) of the PAHs tested in this study (Table S1), and comprised the largest mass percent of the fresh PAH-SOA mass collected on the QFFs (2.46% (± 0.60)) (Figure S2). The only quantifiable DBT-OP detected in the fresh and ozone reacted DBT-SOA was dibenzothiophene sulfone (DBTS). DBTS (2.46% (± 0.76)) accounted for an equal average mass percent as DBT in the fresh DBT-SOA. The sum of DBT and DBTS measured in the DBT-SOA was 4.91% (± 1.31) of the DBT-SOA mass collected. HR-ToF-AMS data shows a large number of peaks in the DBT-SOA extract that were not present in the α-P SOA extract and were not detected using GC/MS (Figure 3B). This suggests that these unidentified compounds were non-volatile. Similarly to PHE, the presence of DBT vapor during SOA formation resulted in ~600% increase in mass loading of DBT-SOA particles.

Upon additional exposure of DBT-SOA to ozone, DBT appeared to represent a somewhat larger wt% of the DBT-SOA (6.86 % (±1.85)) while DBTS remained at 2.29% (±0.49) wt% of the DBT-SOA total mass, but was not statistically significantly different (Table 1). This suggests that DBT and DBTS were shielded from evaporation during the ozone exposure.

Pyrene.

In fresh PYR-SOA, PYR (vapor pressure 6.0 × 10−4 Pa) was measured at 1.79% (± 0.62) of the total PYR-SOA mass, and the combined mass of PYR and all measured PYR-OPs was 3.10% (± 0.88) of the total PYR-SOA mass collected. The sum of PYR and PYR-OPs in these particles is in good agreement with previously reported values (~5%) of the PYR-SOA mass estimated from real-time in-situ mass spectrometric analysis of PYR-SOA particles18. Three individual PYR-OPs were measured in the fresh PYR-SOA, with the main product being 1-OHPYR at 1.25% (± 0.31), and two minor products, 6H-benzo(cd)pyren-6-one (6H-BcdP) at 0.04% (± 0.02) and 4H-cyclopenta(def)pheanathren-4-one (4H-CPP) at 0.07% (Table 1 and Figure S2). 6H-BcdP was measured near the detection limits on 2 of the 3 fresh filters, while 4H-CPP was only measured above the detection limit on one of the 3 fresh PYR-SOA samples. HR-ToF-AMS data, as with the other PAHs, shows a larger abundance of higher m/z peaks in PYR-SOA in comparison to pure α-P SOA (Figure 3C). The presence of PYR vapor during SOA formation resulted in ~320% increase in mass loading of SOA particles. The observed similarities between the normalized mass spectra of pure α-P-SOA and PYR-SOA at lower m/z (Figure 3C), indicate that, as it was a case for other PAHs, the additional mass is dominated by α-P oxidation products.

After PYR-SOA exposure to additional ozone, the PYR concentration was measured to increase, though not statistically significant, from 1.79% (± 0.62) to 6.32% (± 3.42) of the total PYR-SOA mass (Table 1). The 1-OHPYR concentration also appeared to represent a larger wt% of the PYR-SOA (5.91% (± 2.24)) of the total SOA mass, and the 6H-CPP concentration increased from 0.04% (± 0.02) to 0.70% (± 0.22) of the total SOA mass, but was not statistically significantly different. 4H-CdeP was not detected in the ozone-exposed PYR-SOA samples. The lack of statistical difference in the fresh and ozone exposed PYR-SOA is suggestive of the variability in the particle losses during the exposure through the PAM reactor, and supports previous studies showing the retention of PAHs and PAH-OPs in SOA particles, even as more volatile components may leave during atmospheric aging and transport18,24. The ratio of PYR-OPs to PYR concentrations remained relatively unchanged; 0.73 in the fresh PYR-SOA, and 1.05 in the ozone-exposed PYR-SOA. Normalized PYR-OPs to PYR wt% showed no statistically significant difference before and after ozone exposure, indicating that both PYR and the PYR-OPs were shielded from volatilization and oxidation during the high ozone concentration exposure. In addition to 1-OHPYR, a previous laboratory study detected 4-carboxy-5-phenanthrenecarboxylate (4C5PC) as the main PYR-OP during heterogeneous reactions of PYR bound to azelaic acid particles and ozone36. However, 4C5PC was not detected in the QFF extracts of PYR-SOA.

Benz(a)anthracene.

BaA was not detected on the QFF after collection of 15 μg of BaA-SOA from a single Teflon bag, suggesting less incorporation into BaA-SOA than the other PAHs examined in this study, due to the low vapor pressure of BaA (2.8 × 10−5 Pa, Table S1). To overcome this and identify BaA-OPs, 147 μg of BaA-SOA was collected from two individual Teflon bags onto a single QFF (n=1). Only BaA (0.08%) and benz(a)anthracene-7,12-dione (7,12-BaAone) (0.19%) were quantifiable in the QFF extract from the BaA-SOA (Table 1, Figure S2). HR-ToF-AMS data shows a large number of peaks in the BaA-SOA extract that were not present in the α-P SOA extract and were not detected using GC/MS (Figure 3D). This suggests that these unidentified compounds were non-volatile. The presence of BaA vapor during SOA formation resulted in ~140% increase in mass loading of SOA particles. The BaA-SOA was not exposed to additional ozone due to the low concentration of BaA and 7,12-BaAone in the fresh BaA-SOA experiment.

Implications.

While the 16 priority PAHs currently monitored on global pollution lists have well defined toxicity profiles, many PAH-OPs have incomplete or no known toxicity profile38,25,39,40. The PHE-OPs measured in this study have been shown to have different toxic effects than PHE25,39. DBT has been described as a cytochrome P450 A1 inhibitor, and DBTS has been described as having comparable toxicity to DBT in tissue alteration studies25,41. While 1-OHPYR has been described as having comparable toxicity to PYR, 6H-BcdP and 4H-CPP have been measured to possess different toxicity profiles25,3. The US Environmental Protection Agency lists BaA as a human carcinogenic compound42, while 7,12-BaAone has been evaluated for and found to possess developmental toxicity25. There is currently no available data on the mutagenicity or carcinogenicity of this 7,12-BaAone25,42.

This study provides evidence that PAHs are partially oxidized as they become incorporated into SOA particles during particle formation and growth in the presence of PAH vapor. This study, for the first time, quantifies PAHs with a range of vapor pressures, and their PAH-OPs incorporated into SOA particles. Individual PAHs show different reactivity and incorporation into the SOA, partially, but not completely, explained by their respective vapor pressures. The presence of both PAHs and PAH-OPs (which are generally less volatile than PAHs (Table S1)) within SOA supports the proposed mechanism of LRAT of both of these classes of compounds in SOA particles. The semi-solid nature of the SOA particles, at least partially, protects PAHs and PAH-OPs from evaporation or further chemical reactions during atmospheric transport17,18,24,43. The higher mass loadings of SOA produced in the presence of PAH vapor observed in this study, suggest that they contain low-volatility and non-volatile compounds, including oligomers and some PAH-OPs that were not measurable using GC/MS. The increased oligomer signature on HR-ToF-AMS data cannot be attributed to a-pinene or PAH vapor without full analysis of oligomer composition. Along with the observed retention of PAHs and PAH-OPs in particles exposed to ozone in this study, the slower evaporation kinetics observed here, and elsewhere18, suggest that shielding occurs in SOA particles which protects entrapped compounds during LRAT.

The synergy between PAH vapors and SOA formation, highlighted in this work, requires further studies aimed to develop an understanding of the processes involved and their atmospheric implications. Similarly, the relationship between the composition of PAH-SOA particles generated in this study and atmospheric samples is not direct, and needs to be further probed to assess the LRAT of PAHs and PAH-OPs under various atmospheric conditions. While this study evaluated the more volatile PAH-OPs of the PAHs studied here, future studies need to include analysis of low-volatility and non-volatile PAH-SOA constituents. LRAT models of atmospheric SOA particles influenced by anthropogenic activity will continue to be incomplete in their predictions until a better understanding of the chemical composition is known.

To improve LRAT models for more accurate human risk assessment, this area of research requires more comprehensive studies of the underlying processes, the quantification of the many trapped chemical species in SOA particles, such as PAHs and PAH-OPs, and the effects on the global climate and human health these synergistic relationships might have.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This publication was made possible in part by Grant Numbers AGS-1411214 from the National Science Foundation (NSF), and P42-ES016465 and P30-ES00210, from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), National Institute of Health (NIH). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official view of the NIEHS or NIH. Additional support was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Atmospheric Systems Research (ASR) program (K.S., D.B., A,Z.). (A portion of) The research was performed using EMSL (Ringgold ID 130367), a DOE Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Tables S1-S4 provide additional information on the chemicals in this study, as well as detailed GC/MS methods, sample preparation, and standard purity testing. Figure S1 shows non-targeted screening of PAH-SOA extracts. Figure S2 shows DBT, PYR, and BaA results graph for fresh PAH-SOA.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Primbs T; Piekarz A; Wilson G; Schmedding D; Higginbotham C; Field J; Simonich SM, Influence of Asian and Western United States Urban Areas and Fires on the Atmospheric Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Polychlorinated Biphenyls, and Fluorotelomer Alcohols in the Western United States. Environmental Science & Technology 2008, 42 (17), 6385–6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman CL; Selin NE, Long-Range Atmospheric Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: A Global 3-D Model Analysis Including Evaluation of Arctic Sources. Environmental Science & Technology 2012, 46 (17), 9501–9510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knecht AL; Goodale BC; Truong L; Simonich MT; Swanson AJ; Matzke MM; Anderson KA; Waters KM; Tanguay RL, Comparative developmental toxicity of environmentally relevant oxygenated PAHs. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2013, 271 (2), 266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thackray CP; Friedman CL; Zhang Y; Selin NE, Quantitative Assessment of Parametric Uncertainty in Northern Hemisphere PAH Concentrations. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49 (15), 9185–9193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang R; Liu G; Zhang J, Variations of emission characterization of PAHs emitted from different utility boilers of coal-fired power plants and risk assessment related to atmospheric PAHs. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 538, 180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y; Hong B; Fan Y; Wen M; Han X, Accurate analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and alkylated PAHs homologs in crude oil for improving the gas chromatography/mass spectrometry performance. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2014, 100 (Supplement C), 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Shafy HI; Mansour MSM, A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum 2016, 25 (1), 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiraiwa M; Ueda K; Pozzer A; Lammel G; Kampf CJ; Fushimi A; Enami S; Arangio AM; Fröhlich-Nowoisky J; Fujitani Y; Furuyama A; Lakey PSJ; Lelieveld J; Lucas K; Morino Y; Pöschl U; Takahama S; Takami A; Tong H; Weber B; Yoshino A; Sato K, Aerosol Health Effects from Molecular to Global Scales. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51 (23), 13545–13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurston GD; Kipen H; Annesi-Maesano I; Balmes J; Brook RD; Cromar K; De Matteis S; Forastiere F; Forsberg B; Frampton MW; Grigg J; Heederik D; Kelly FJ; Kuenzli N; Laumbach R; Peters A; Rajagopalan ST; Rich D; Ritz B; Samet JM; Sandstrom T; Sigsgaard T; Sunyer J; Brunekreef B, A joint ERS/ATS policy statement: what constitutes an adverse health effect of air pollution? An analytical framework. European Respiratory Journal 2017, 49 (1), 1600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landrigan PJ; Fuller R; Acosta NJR; Adeyi O; Arnold R; Basu N; Baldé AB; Bertollini R; Bose-O’Reilly S; Boufford JI; Breysse PN; Chiles T; Mahidol C; Coll-Seck AM; Cropper ML; Fobil J; Fuster V; Greenstone M; Haines A; Hanrahan D; Hunter D; Khare M; Krupnick A; Lanphear B; Lohani B; Martin K; Mathiasen KV; McTeer MA; Murray CJL; Ndahimananjara JD; Perera F; Potočnik J; Preker AS; Ramesh J; Rockström J; Salinas C; Samson LD; Sandilya K; Sly PD; Smith KR; Steiner A; Stewart RB; Suk WA; van Schayck OCP; Yadama GN; Yumkella K; Zhong M, The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet 2018, 391 (10119), 462–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu SN; Sands S; Tomasik MR; Lee PS; McNeill VF, Ozone Oxidation of Surface-Adsorbed Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Role of PAH−Surface Interaction. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010, 132 (45), 15968–15975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang WT; Jariyasopit N; Schrlau J; Jia YL; Tao S; Yu TW; Dashwood RH; Zhang W; Wang XJ; Simonich SLM, Concentration and Photochemistry of PAHs, NPAHs, and OPAHs and Toxicity of PM2.5 during the Beijing Olympic Games. Environmental Science & Technology 2011, 45 (16), 6887–6895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jariyasopit N; McIntosh M; Zimmermann K; Arey J; Atkinson R; Cheong PH-Y; Carter RG; Yu T-W; Dashwood RH; Massey Simonich SL, Novel Nitro-PAH Formation from Heterogeneous Reactions of PAHs with NO2, NO3/N2O5, and OH Radicals: Prediction, Laboratory Studies, and Mutagenicity. Environmental Science & Technology 2014, 48 (1), 412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahpoury P; Lammel G; Albinet A; Sofuoǧlu A; Dumanoğlu Y; Sofuoǧlu SC; Wagner Z; Zdimal V, Evaluation of a Conceptual Model for Gas-Particle Partitioning of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Using Polyparameter Linear Free Energy Relationships. Environmental Science & Technology 2016, 50 (22), 12312–12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davie-Martin CL; Stratton KG; Teeguarden JG; Waters KM; Simonich SLM, Implications of Bioremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Soils for Human Health and Cancer Risk. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51 (17), 9458–9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sindelarova K; Granier C; Bouarar I; Guenther A; Tilmes S; Stavrakou T; Muller JF; Kuhn U; Stefani P; Knorr W, Global data set of biogenic VOC emissions calculated by the MEGAN model over the last 30 years. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2014, 14 (17), 9317–9341. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zelenyuk A; Imre D; Beranek J; Abramson E; Wilson J; Shrivastava M, Synergy between Secondary Organic Aerosols and Long-Range Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environmental Science & Technology 2012, 46 (22), 12459–12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zelenyuk A; Imre DG; Wilson J; Bell DM; Suski KJ; Shrivastava M; Beranek J; Alexander ML; Kramer AL; Massey Simonich SL, The effect of gas-phase polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on the formation and properties of biogenic secondary organic aerosol particles. Faraday Discussions 2017, 200 (0), 143–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walgraeve C; Demeestere K; Dewulf J; Zimmermann R; Van Langenhove H, Oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmospheric particulate matter: Molecular characterization and occurrence. Atmospheric Environment 2010, 44 (15), 1831–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Socorro J; Lakey PSJ; Han L; Berkemeier T; Lammel G; Zetzsch C; Pöschl U; Shiraiwa M, Heterogeneous OH Oxidation, Shielding Effects, and Implications for the Atmospheric Fate of Terbuthylazine and Other Pesticides. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51 (23), 13749–13754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehn M; Thornton JA; Kleist E; Sipilä M; Junninen H; Pullinen I; Springer M; Rubach F; Tillmann R; Lee B; Lopez-Hilfiker F; Andres S; Acir I-H; Rissanen M; Jokinen T; Schobesberger S; Kangasluoma J; Kontkanen J; Nieminen T; Kurtén T; Nielsen LB; Jørgensen S; Kjaergaard HG; Canagaratna M; Maso MD; Berndt T; Petäjä T; Wahner A; Kerminen V-M; Kulmala M; Worsnop DR; Wildt J; Mentel TF, A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol. Nature 2014, 506, 476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perraudin E; Budzinski H. l. n.; Villenave E, Identification and quantification of ozonation products of anthracene and phenanthrene adsorbed on silica particles. Atmospheric Environment 2007, 41 (28), 6005–6017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Archibald A; Arnold S; Bejan L; Brown S; Bruggemann M; Carpenter LJ; Collins W; Evans M; Finlayson-Pitts B; George C; Hastings M; Heard D; Hewitt CN; Isaacman-VanWertz G; Kalberer M; Keutsch F; Kiendler-Scharr A; Knopf D; Lelieveld J; Marais E; Petzold A; Ravishankara A; Reid J; Rovelli G; Scott C; Sherwen T; Shindell D; Tinel L; Unger N; Wahner A; Wallington TJ; Williams J; Young P; Zelenyuk A, Atmospheric chemistry and the biosphere: general discussion. Faraday Discussions 2017, 200 (0), 195–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrivastava M; Lou S; Zelenyuk A; Easter RC; Corley RA; Thrall BD; Rasch PJ; Fast JD; Massey Simonich SL; Shen H; Tao S, Global long-range transport and lung cancer risk from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons shielded by coatings of organic aerosol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114 (6), 1246–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geier MC; Chlebowski AC; Truong L; Massey Simonich SL; Anderson KA; Tanguay RL, Comparative developmental toxicity of a comprehensive suite of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Archives of Toxicology 2018, 92 (2), 571–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schummer C; Delhomme O; Appenzeller BMR; Wennig R; Millet M, Comparison of MTBSTFA and BSTFA in derivatization reactions of polar compounds prior to GC/MS analysis. Talanta 2009, 77 (4), 1473–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaden TD; Imre D; Beránek J; Shrivastava M; Zelenyuk A, Evaporation kinetics and phase of laboratory and ambient secondary organic aerosol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108 (6), 2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abramson E; Imre D; Beránek J; Wilson J; Zelenyuk A, Experimental determination of chemical diffusion within secondary organic aerosol particles. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15 (8), 2983–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nah T; Sanchez J; Boyd CM; Ng NL, Photochemical Aging of α-pinene and β-pinene Secondary Organic Aerosol formed from Nitrate Radical Oxidation. Environmental Science & Technology 2016, 50 (1), 222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeCarlo PF; Kimmel JR; Trimborn A; Northway MJ; Jayne JT; Aiken AC; Gonin M; Fuhrer K; Horvath T; Docherty KS; Worsnop DR; Jimenez JL, Field-Deployable, High-Resolution, Time-of-Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer. Analytical Chemistry 2006, 78 (24), 8281–8289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroll JH; Lim CY; Kessler SH; Wilson KR, Heterogeneous Oxidation of Atmospheric Organic Aerosol: Kinetics of Changes to the Amount and Oxidation State of Particle-Phase Organic Carbon. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2015, 119 (44), 10767–10783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambe AT; Ahern AT; Williams LR; Slowik JG; Wong JPS; Abbatt JPD; Brune WH; Ng NL; Wright JP; Croasdale DR; Worsnop DR; Davidovits P; Onasch TB, Characterization of aerosol photooxidation flow reactors: heterogeneous oxidation, secondary organic aerosol formation and cloud condensation nuclei activity measurements. Atmos Meas Tech 2011, 4 (3), 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berset JD; Ejem M; Holzer R; Lischer P, Comparison of different drying, extraction and detection techniques for the determination of priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in background contaminated soil samples. Analytica Chimica Acta 1999, 383 (3), 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berndt T; Herrmann H; Kurtà T, Direct Probing of Criegee Intermediates from Gas-Phase Ozonolysis Using Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139 (38), 13387–13392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krapf M; El Haddad I; Bruns Emily A.; Molteni U; Daellenbach Kaspar R.; Prévôt André S. H.; Baltensperger U; Dommen J, Labile Peroxides in Secondary Organic Aerosol. Chem 2016, 1 (4), 603–616. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao S; Zhang Y; Meng J; Shu J, Online investigations on ozonation products of pyrene and benz[a]anthracene particles with a vacuum ultraviolet photoionization aerosol time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Atmospheric Environment 2009, 43 (21), 3319–3325. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Titaley IA; Ogba OM; Chibwe L; Hoh E; Cheong PHY; Simonich SLM, Automating data analysis for two-dimensional gas chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry non-targeted analysis of comparative samples. Journal of Chromatography A 2018, 1541, 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chibwe L; Geier MC; Nakamura J; Tanguay RL; Aitken MD; Simonich SLM, Aerobic Bioremediation of PAH Contaminated Soil Results in Increased Genotoxicity and Developmental Toxicity. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49 (23), 13889–13898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schrlau JE; Kramer AL; Chlebowski A; Truong L; Tanguay RL; Simonich SLM; Semprini L, Formation of Developmentally Toxic Phenanthrene Metabolite Mixtures by Mycobacterium sp. ELW1. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51 (15), 8569–8578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Titaley IA; Chlebowski A; Truong L; Tanguay RL; Massey Simonich SL, Identification and Toxicological Evaluation of Unsubstituted PAHs and Novel PAH Derivatives in Pavement Sealcoat Products. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2016, 3 (6), 234–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva KT; Oliveira-Castro RA; Rodrigues V. c. C.; de Lima WG; Rodrigues CV; Castro-Borges W; Andrade M. H. r. G., DBT- and DBTO2-Induced Dysplasia and Their Associated Proteomic Alterations in the Small Intestines of Wistar Rats. Journal of Proteome Research 2015, 14 (1), 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agency, U. S. E. P., Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Chemical Assessment Summary: Benz[a]anthracene; CASRN 56-55-3.

- 43.Zhou S; Lee AKY; McWhinney RD; Abbatt JPD, Burial Effects of Organic Coatings on the Heterogeneous Reactivity of Particle-Borne Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) toward Ozone. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2012, 116 (26), 7050–7056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miet K; Le Menach K; Flaud PM; Budzinski H; Villenave E, Heterogeneous reactions of ozone with pyrene, 1-hydroxypyrene and 1-nitropyrene adsorbed on particles. Atmospheric Environment 2009, 43 (24), 3699–3707. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cochran RE; Jeong H; Haddadi S; Fisseha Derseh R; Gowan A; Beránek J; Kubátová A, Identification of products formed during the heterogeneous nitration and ozonation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Atmospheric Environment 2016, 128, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.