Abstract

Children less than 6 years have the greatest risk for accidental ingestion and poisoning.

Keywords: Poisoning, Iron ingestion, Head trauma, Drowning, Wounds, Puncture wounds, Animal and human bites, Status epilepticus, Burns, Resuscitation

Poisoning

Background

Children less than 6 years have the greatest risk.

Adolescent exposure either intentional or occupational

Plant ingestions either substance experimentation or attempted self-harm

The website http://www.aapcc.org contains useful information about poison centers

Prevention of poisoning

Child-resistant packaging

Anticipatory guidance in well child care

Poison proofing child’s environment, e.g., labeling and locked cabinets

Parents to utilize online sources and contact poison control emergency number

Carbon monoxide detectors

Maintenance of fuel-burning appliances

Yearly inspection of furnaces, gas pipes, and chimneys

Car inspection for exhaust system

No running engine in a closed garage

Avoid indoor use of charcoal and fire sources

Evaluation of unknown substance

Call poison control center, describe the toxin, read the label, and follow the instruction

Pattern of toxidrome

Amount of exposure, number of pills, number of the remaining pills, amount of liquid remaining

Time of exposure

Progression of symptoms

Consider associated ingestions and underlying medical conditions

General measures for toxic exposures

Emergency department evaluation in ingestion of a large or potential toxic doses

Wash the skin with soap and water

Activated charcoal absorb the substances and decreases bioavailability

-

Activated charcoal is ineffective in the following; CHEMICaL:

- Caustics

- Hydrocarbons

- Ethanol (alcohols)

- Metals

- Iron

- Cyanide

- Lithium

Ipecac no longer used, and induction of emesis is contraindicated in hydrocarbons and caustics

-

Gastric lavage

- Contraindicated in hydrocarbons, alcohols and caustics

- It can be used if life-threatening ingestion within 30–60 min

Whole bowel irrigation

Anticholinergic Ingestion

Agents

Diphenhydramine, atropine, Jimsonweed (Datura Stramonium), and deadly night shade (Atropa Belladonna)

Background

Jimson weed and deadly night shade produce anticholinergic toxins, e.g., atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine

Common garden vegetables in the solanum genus, including tomatoes, potatoes, and eggplants.

Cause anticholinergic symptoms

Clinical presentation (anticholinergic symptoms)

Dry as a bone: Dry mouth, decrease sweating, and urination

Red as a beet: Flushing

Blind as a bat: Mydriasis, blurred vision

Mad as a hatter: Agitation, seizures, Hallucinations

Hot as a hare: Hyperthermia

Bloated as a Toad (ileus, urinary retention)

Heart runs alone (tachycardia)

Management

Activated charcoal

Physostigmine may be indicated to treat severe or persistent symptoms

Carbamazepine Ingestion

Mild ingestion

Central nervous system (CNS) depression

Drowsiness

Vomiting

Ataxia

Slurred speech

Nystagmus

Severe intoxication

Seizures

Coma

Respiratory depression

Treatment

Activated charcoal

Supportive measures

Charcoal hemoperfusion can be effective for severe intoxication

Clonidine

Antihypertensive medication with α-2 adrenergic receptor blocking ability

Commonly used in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

A dose as small as 0.1 mg can cause toxicity in children

Common symptoms

Lethargy

Miosis

Bradycardia

Hypotension but it may cause hypertension

Apnea

Treatment

Supportive care, e.g., intubation, atropine, dopamine as needed

Electroencephalogram (EEG), blood gases

Toxicity usually resolve in 24 h

Opiates

Common opiates

Morphine, heroin, methadone, propoxyphene, codeine, meperidine

Most cases are drug abuse

Symptoms

Common triad of opiate poisoning (pinpoint pupil, coma, respiratory depression)

Drowsiness to coma

Miosis

Change in mood

Analgesia

Respiratory depression

Hypotension with no change in heart rate (HR)

Decreased gastrointestinal (GI) motility

Nausea and vomiting

Abdominal pain

Treatment

Airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs)

Intubation if necessary

Naloxone as needed

Phenothiazine Ingestion

Common drugs

Promethazine (Phenergan), prochlorperazine, and chlorpromazine

Symptoms

Hypertension

Cogwheel rigidity

Dystonic reaction (spasm of the neck, tongue thrusting, oculogyric crisis)

CNS depression

Treatment

Charcoal

Manage blood pressure

Diphenhydramine for dystonic reaction

Foxglove (Digitalis) Ingestion

Source

Foxglove plants.

Produces cardioactive glycosides.

They are also found in lily of the valley (Convallaria).

Clinical presentation

Similar to digoxin toxicity

Hyperkalemia

CNS depression

Cardiac conduction abnormalities

Treatment

Digoxin-specific antibody fragments can be lifesaving

Seeds (Cherries, Apricots, Peaches, Apples, Plums) Ingestion

Amygdalin is contained in seeds and produces hydrogen cyanide which is a potent toxin

Inhibition of cellular respiration and can be lethal

Mushrooms Ingestion

Ingestion of mushrooms also may have fatal consequences in species that harbor amatoxins (Amanita) and related compounds

Clinical presentation

Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; delayed onset (6 h)

A second latent period is followed by acute and possibly fulminant hepatitis beginning 48–72 h after ingestion

Management

Activated charcoal

Whole bowel irrigation

Supportive care, including liver transplant if necessary, is the mainstay of therapy

Acetaminophen Ingestion

Background

The single toxic acute dose is generally considered to be > 200 mg/kg in children and more 7.5–10 g in adult and can cause hepatic injury or liver failure

Any child with history of acute ingestion of > 150 mg/kg of acetaminophen should be referred for assessment and measurement of acetaminophen level

Clinical presentation

-

First 24 h

- Asymptomatic or nonspecific signs

- Nausea, vomiting, dehydration, diaphoresis, and pallor

- Elevation of liver enzyme

-

24–72 h after ingestion

- Tachycardia and hypotension

- Right upper quadrant pain with or without hepatomegaly

- Liver enzyme is more elevated

- Elevated prothrombin time (PT) and bilirubin in severe cases

-

3–4 days post ingestion

- Liver failure

- Encephalopathy, with or without renal failure

- Possible death from multi-organ failure or cerebral edema

-

4–14 days post ingestion

- Complete recovery or death

Management

Measure serum acetaminophen level 4 h after the reported time of ingestion

Acetaminophen level obtained < 4 h after ingestion cannot be used to estimate potential toxicity

Check acetaminophen level 6–8 h if it is co-ingested with other substance slow GI motility, e.g., diphenhydramine

-

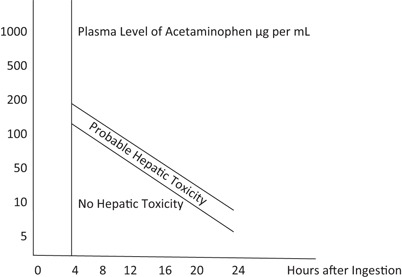

Rumack–Matthew nomogram (Fig. 1)

- Plot 4-h value of a single acute ingestion

- Risk of hepatotoxicity possible if 4-h level is equal or greater than 150 mcg/ml. If fall on upper line (200 mcg/ml at 4 h) hepatotoxicity is probable

-

Assess the liver function

- Obtain hepatic transaminases level, renal function tests, and coagulation parameters

If acetaminophen level > 10 μg/ml even with normal liver function, start the N-acetylcysteine (NAC)

If acetaminophen level is low or undetectable with abnormal liver function, NAC should be given

Patients with a history of potentially toxic ingestion more than 8 h after ingestion should be given the loading dose of NAC and decision to continue treatment should be based on acetaminophen level or liver function test

NAC therapy is most effective when initiated within 8 h of ingestion

Liver transplant if severe hepatotoxicity

Consult poison control center at 1-800-222-1222

Fig. 1.

Rumack–Mathew nomogram for acetaminophen poisoning. (Adapted from Rumack BH, Mathew H. Acetaminophen poisoning and toxicity. Pediatrics 55:971–876, 1975)

Ibuprofen Ingestion

Background

Inhibit prostaglandin synthesis

May cause GI irritation, ulcers, decrease renal blood flow, and platelet dysfunction

Dose > 400 mg/kg can cause seizure and coma

Dose < 100 mg/kg usually does not cause toxicity

Clinical presentation

Nausea, vomiting and epigastric pain

Drowsiness, lethargy, and ataxia may occur

Anion gap metabolic acidosis, renal failure, seizure and coma may occur in severe cases

Management

Activated charcoal

Supportive care

Salicylic acid Ingestion

Products contain an aspirin

Baby aspirin

Regular aspirin at home includes: Anti-diarrheal medications, topical agents, e.g., keratolytics and sport creams

Toxic dose

Refer to emergency departments for ingestions > 150 mg/kg

Ingestion of > 200 mg/kg is generally considered toxic, > 300 mg/kg is more significant toxicity, > 500 mg/kg is potentially fatal

Clinical presentation

Acute salicylism; nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and tinnitus

Tachypnea, hyperpnea, tachycardia, and altered mental status can be seen in moderate toxicity

Hyperthermia and coma are seen in severe acetylsalicylic acid toxicity

Diagnosis

Classic blood gas of salicylic acid toxicity is respiratory alkalosis, metabolic acidosis, and high anion gap

Check serum level every 2 h until it is consistently down trending

Management

Initial treatment is gastric decontamination with activated charcoal, volume resuscitation, and prompt initiation of sodium bicarbonate therapy in the symptomatic patients

Goal of therapy includes a urine pH of 7.5–8.0, a serum pH of 7.5–7.55, and decreasing salicylate levels

Tricyclic Antidepressants Ingestion

Toxicity

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can cause significant toxicity in children even with ingestion of 1–2 pills (10–20 mg/kg)

Clinical presentation

It gives the clinical feature of anticholinergic toxidrome; delirium, mydriasis, dry mucous membrane, tachycardia, hyperthermia, hypotension, and urinary retention

Cardiovascular and CNS symptoms dominate the clinical presentation

Most common cardiac manifestations; widening of QRS complex, premature ventricular contractions, ventricular arrhythmia

Refractory hypotension is poor prognostic indicator, and is the most common cause of death in TCAs toxicity

Electrocardiography

A QRS duration > 100 ms identifies patients who risk for seizures and cardiac arrhythmia

An R wave in lead aVR of > 3 mm is independent predictor of toxicity

Electrocardiography (ECG) parameter is superior to measured serum of TCAs

Management

Stabilization of patient is the most important initial step specially protecting the airway, and ventilation support as needed, activated charcoal in appropriate patients

Obtain ECG as soon as possible

ECG indication for sodium bicarbonate therapy include: QRS duration > 100 ms, ventricular dysrhythmias and hypotension

Caustic Ingestion

Background

Strong acid and alkalis < 2 or > 12 pH can produce severe injury even in small-volume ingestion

Patient can have significant esophageal injury without visible oral burns.

Clinical presentation

Pain , drooling, vomiting, and abdominal pain

Difficulty in swallowing, or refusal to swallow

Stridor, and respiratory distress are common presenting symptoms

Esophageal stricture caused by circumferential burn and require repeated dilation or surgical correction

Management

Emesis and lavage are contraindicated

Endoscopy should be performed within 12–24 h in symptomatic patients, or on basis of history and characteristics of ingested products

Organophosphate and Insecticide Exposure

Clinical presentation

DUMBBELLS - Diarrhea, Urination, Miosis, Bradycardia, Bronchospasm, Emesis, Lacrimation, Lethargy, Salivation, and Seizures

Management

Wash all exposed skin with soap and water and immediately remove all exposed clothing

Fluid and electrolyte replacement, intubation, and ventilation, if necessary

Antidote is atropine and pralidoxime

Hydrocarbon Ingestion

Products contain hydrocarbon substances

Mineral spirits, kerosene, gasoline, turpentine, and others

Clinical presentation

Aspiration of small amount of hydrocarbons can lead to serious, and potentially, life-threatening toxicity

Pneumonitis is the most important manifestation of hydrocarbon toxicity

Benzene is known to cause cancer, most commonly acute myelogenous leukemia

Inhalants can cause dysrhythmias and sudden death including toluene, propellants, volatile nitrite, and the treatment is beta blocker

Management

Emesis and lavage are contraindicated

Activated charcoal should be avoided due to risk of inducing vomiting

Observation and supportive care, each child who is not symptomatic should be observed for at least 4–6 h in Emergency department (ED)

Neither corticosteroids or prophylactic antibiotics have shown any clear benefits

Methanol Ingestion

Toxicity primarily caused by formic acid

Clinical presentation

Drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting

Metabolic acidosis

Visual disturbances; blurred and cloudy vision, feeling being in snow storm, untreated cases can lead to blindness

Management

Methanol blood level and osmolar gap may be used as surrogate marker

IV fluids, glucose and bicarbonate as needed for electrolyte imbalances/dehydration

Fomepizole is the most preferred antidote for both methylene and ethylene glycol. Ethanol can be used if Fomepizole is unavailable

If > 30 ml methanol ingested, consider hemodialysis

Ethylene Glycol Ingestion (Antifreeze)

Clinical presentation

Nausea, vomiting, CNS depression, anion gap metabolic acidosis

Hypocalcemia, renal failure due to deposition of calcium oxalate crystals in the renal tubules

Management

Osmolar gap can be used to estimate ethylene glycol level

IV fluids, glucose and bicarbonate as needed for electrolyte imbalances/dehydration

Fomepizole the most preferred antidote for both methylene and ethylene glycol. Ethanol can be used if Fomepizole is unavailable

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

Sources of CO

Wood-burning stove, old furnaces, and automobiles

Clinical presentation

Headache , malaise, nausea, and vomiting are the most common flu or food poisoning like early symptoms

Confusion, ataxia, syncope, tachycardia, and tachypnea at higher exposure

Coma, seizure, myocardial ischemia, acidosis, cardiovascular collapse, and potentially death in severe cases

Management

Evaluate for COHb level in symptomatic patients; arterial blood gas with CO level, creatine kinase in severe cases, and ECG in any patient with cardiac symptoms

100 % oxygen to enhance elimination of CO, use until CO < 10 % and symptoms resolve

Severely poisoned patient may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen specially if COHb > 25 %, significant CNS symptoms, or cardiac dysfunction

Iron Ingestion

Background

It is a common cause of pediatric poisoning.

Ingestion of > 60 mg/kg/dose is toxic

Clinical presentation

-

Gastrointestinal stage (30 min−6 h)

- Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain

- Hematemesis, and bloody diarrhea in severe cases

-

Stability stage (6–24 h)

- No symptoms: Patient must be observed during this stage

-

Systemic toxicity within (48 h)

- Cardiovascular collapse

- Severe metabolic acidosis

Hepatotoxicity and liver failure (2–3 days)

Gastrointestinal and pyloric scarring (2–6 weeks)

Management

-

Abdominal X-ray

- May show the pill

- Chewable and liquid form vitamins usually not visible

Serum iron < 300 mcg/dl in at hours is nontoxic

Iron blood level > 500 mcg/dl is toxic

Treatment

Chelation with IV deferoxamine if serum iron > 500 mcg/dl (Table 1)

Table 1.

Common antidotes for poisoning

| Poison | Antidote |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | N-Acetylcysteine (mucomyst) |

| Anticholinergics | Physostigmine |

| Benzodiazepines | Flumazenil |

| β-blockers | Glucagon |

| Calcium channel blockers | Insulin and calcium salts |

| Carbon monoxide | Oxygen |

| Cyanide | Nitrates |

| Digitalis | Digoxin-specific fragments antigen-binding(Fab) antibodies |

| Ethyleneglycol and methanol | Fomepizole |

| Iron | Deferoxamine |

| Isoniazid (INH) | Pyridoxine |

| Lead and other heavy metals, e.g., mercury and arsenic | BAL (dimercaprol) |

| Methemoglobinemia | Methylene blue |

| Opioids | Naloxone |

| Organophosphates | Atropine and pralidoxime |

| Salicylates | Sodium bicarbonate |

| Sulfonylureas | Octreotide |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Sodium bicarbonate |

Head Trauma

Most head trauma are not serious and require only observation.

Physical signs of possible serious injuries

-

Basilar skull fracture

- Raccoon eyes

- Battle’s sign

- Hemotympanum

-

Temporal fracture

- Potential middle meningeal artery injury

- Hearing loss

- Facial paralysis

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhea

- Facial paralysis

Scalp swelling or deep lacerations

Pupillary changes

-

Retinal hemorrhage and bruises

- In infant indicate possible abuse

Indication for head CT scan

Change in mental status

Loss of consciousness more than 1 min

Acute skull fracture

Bulging fontanelle

Signs of basilar skull fracture

Focal neurological sign

Seizures

Irritability

Persistent vomiting

Management of head trauma

Protection of airway if unresponsive or Glasgow Coma Scale less than 8

Intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring

Maintain cerebral perfusion pressure at 40 mmHg

IV mannitol or 3 % saline if increased ICP

Mild hyperventilation

Control hyperthermia

Consult neurosurgery

Drowning

Drowning is a major cause in head injuries and death

-

Initial peak

- Toddler age group

-

Second peak

- Male adolescents

-

Children younger than 1 year of age

- Often drown in bathtubs, buckets, and toilets

-

Children 1–4 years of age

- Likely drown in swimming pools where they have been unsupervised temporarily (usually for < 5 min)

- Typical incidents involve a toddler left unattended temporarily or under the supervision of an older sibling

-

Adolescent and young adult age groups (ages 15–24 years)

- Most incidents occur in natural water

Approximately 90 % of drowning occur within 10 yards of safety

Parent should be within an arm’s length of a swimming child (anticipatory guidance)

Mechanism of injury

Initial swallowing of water

Laryngospasm

Loss of consciousness

Hypoxia

Loss of circulation

Ischemia

CNS injury (the most common cause of death)

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may develop

-

Salt water drowning classically associated with:

- Hypernatremia

- Hemoconcentration

- Fluid shifts and electrolyte disturbances are rarely seen clinically

-

Fresh water drowning classically associated with:

- Hyponatremia and hemodilution

- Hyperkalemia

- Hemoglobinuria and renal tubular damage

-

Management of drowning and near drowning

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) at the scene

- Admit regardless of clinical status

- All children with submersion should be monitored in the hospital for 6–8 h

- If no symptoms develop can be discharged safely

- 100 % oxygen with bag and mask immediately

- Nasogastric tube for gastric decompression

- Cervical spine immobilization if suspected cervical injuries

- Positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) and positive pressure ventilations in case of respiratory arrest

- Continuous cardiac monitoring

- Bolus of normal saline or Ringer’s lactate

- Vasopressors

- Defibrillation if indicated

Wounds

General principles of wound care

The time and mechanism of injury because these factors relate to subsequent management options.

Accidental or non-accidental trauma

The timing of the injury may affect management (lacerations > 8–24 h old may not be repaired depending on location).

Acute wounds often can be repaired primarily

Older wounds may require delayed primary closure or healing by secondary intention

Hemostasis

Persistent bleeding despite direct pressure can be controlled with the careful application of a tourniquet above the injury

The use of tourniquets may lead to ischemia, and the need for a tourniquet can indicate a more severe soft tissue or vascular injury that may require surgery

Blood pressure cuff inflated to suprasystolic pressures is effective

-

Local infiltration with lidocaine containing epinephrine; except:

- Digits

- Ears

- Nose

- Penis

Wound cleaning

Decontamination of the wound is the most important step in preventing infectious complications.

Irrigation.

Removal of foreign material from the wound is essential to minimize the risk of infection

Dressings

Once the wound has been evaluated, decontaminated, and repaired, an appropriate dressing should be applied

Topical antibiotic ointments (e.g., bacitracin) and an occlusive dressing (moist wound heals better)

Dressings can be left in place for 24–48 h and then changed once or twice daily

Wounds that cross joints may require splinting or bulky dressings to minimize movement and tension on the wound

Prophylaxis

All children who have cutaneous wounds should have their tetanus status reviewed and appropriate prophylaxis administered

Empiric use of antibiotics is not indicated except bites

Puncture Wounds

Background

Most are plantar puncture wounds from nails, punctures also can occur in other parts of the body.

Immediate evaluation should assess for any life-threatening injuries, especially for puncture wounds of the head, neck, chest, and abdomen

Particular attention should be paid to wound depth, possible retained foreign bodies, and risk of infection

Evaluation

Timing and mechanism of the injury

Puncture wounds that are older than 6 h, occur from bites, have retained foreign body or vegetative debris, or extend to a significant depth have a higher risk of infection

Radiography may help identify a retained foreign body or fracture

Ultrasonography is a convenient, radiation-free, and highly sensitive modality for identifying retained foreign bodies

Management

Most puncture wounds can be managed in the outpatient setting with an antibiotic, dressing and warm soaks

Most infected puncture wounds are caused by S. aureus or S. pyogenes, and respond to oral antibiotics

Infected puncture wounds that result from a nail through a tennis shoe should be evaluated for possible pseudomonas aeruginosa infection

Additional imaging and intravenous antibiotics may be necessary to treat more serious infections, including cellulitis, abscess, osteochondritis, and osteomyelitis

Surgical consultation for potential debridement or retained foreign body removal should be considered for wounds refractory to medical management

Lacerations

Laceration is a traumatic disruption to the dermis layer of the skin

The most common anatomic locations for lacerations are the face (~ 60 %) and upper extremities (~ 25 %)

Evaluation

An evaluation for life-threatening injuries is the first priority

Ongoing bleeding that may cause hypovolemic shock

Applying direct pressure usually is successful

Sphygmomanometer may be used for up to 2 h on an extremity

Ring tourniquet on a digit for up to 30 min to help control ongoing blood loss

Lacerations of the neck should be evaluated for deeper structural injuries

If developmentally appropriate, two-point discrimination at the finger pads provides the best assessment of digital nerve function

It is critical to identify foreign material within the laceration

Anesthetics and anxiolysis

The use of the topical anesthetic LET (4 % Lidocaine, 1:2000 Epinephrine, and 0.5 %Tetracaine) has been shown to be effective and to reduce length of stay

LET usually is effective 20–30 min after application to a laceration site on the face but often needs twice that amount of time to be effective elsewhere

Blanching of the site after application most often indicates achievement of effective anesthesia

A local anesthetic also may be used to prepare for placement of sutures

Closure of lacerations

Dermabond: It is critical that the laceration be dry and well approximated to avoid application below the epidermal surface, which may cause the wound to gape open or lead to a “Dermabond Oma”

Evenly spaced suture placement: The general rule is sutures should be spaced the same distance as they are placed from the wound edge. For irregular wound shapes, approximate the midpoint of the wound first and then work laterally

Lip lacerations

Lip laceration require special care if the injury crosses the vermilion border

It is essential to approximate the vermilion border with a suture. Failure to do so may result in a poor cosmetic outcome

An infraorbital or mental nerve block along the lower gum line may be considered to reduce tissue distortion for lip lacerations, including those through the vermilion border

Lacerations of the nail bed

It may be painful and produce anxiety for the child and parent

A digital nerve block should be applied to provide adequate analgesia for this injury

If the nail has been removed during the injury, the nail bed should be repaired with absorbable sutures by using a reverse cutting needle

The nail should be placed under the eponychium (cuticle) to preserve this space

If a nail is not available, a small piece of sterile aluminum foil from the suture pack may be used as a substitute for 3 weeks

If possible, a small hole can be placed in the nail plate to allow for drainage and to avoid a subungual hematoma

The nail can be secured with tissue adhesive and tape adhesive

Approximately half of all nail bed injuries are associated with a fracture of the distal phalanx

No evidence that antimicrobial prophylaxis reduces the rate of infection

Most hand surgeons recommend a 3- to 5-day course of antibiotic (e.g., cephalexin)

Wrapping dressings too tightly around the digit should be avoided because this may cause tissue ischemia and infarction

Daily dressing changes are recommended to evaluate the wound

Removal times for sutures (sutures removed before 7 days are unlikely to leave suture tracks)

Face 3–5 days

Scalp 5–7 days

Trunk 5–7 days

Extremities 7–10 days

Joints 10–14 days

Animal and Human Bites

Dog Bites

Dog bite causes a crushing-type wound.

Extreme pressure of dog bite may damage deeper structures such as bones, vessels, tendons, muscle, and nerves.

Cat Bites

The sharp pointed teeth of cats usually cause puncture wounds and lacerations that may inoculate bacteria into deep tissues

Infections caused by cat bites generally develop faster than those of dogs

Other Animals

Foxes, raccoons, skunks, and bats exposure are a high risk for rabies

Human Bites

Three general types of injuries can lead to complications:

Closed-fist injury

Chomping injury to the finger

Puncture-type wounds about the head caused by clashing with a tooth

Common bacteria involved in bite wound infections include the following:

Dog bites

Staphylococcus species

Eikenella species

Pasteurella species

Cat bites

Pasteurella species

Bacteroides species

Human bites

Eikenella Corrodens

Staphylococcus, Streptococcus

Staphylococcus aureus is associated with some of the most severe infections

-

Human bites can transmit the following organism:

- Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and syphilis

Clinical presentation

Time and location of event

Type of animal and its status (i.e., health, rabies vaccination history, behavior,)

Circumstances surrounding the bite (i.e., provoked or defensive bite versus unprovoked bite)

Location of bites (most commonly on the upper extremities and face)

Laboratory

Fresh bite wounds without signs of infection do not need to be cultured

Infected bite wounds should be cultured to help guide future antibiotic therapy

CBC and blood culture if clinically required.

Imaging studies

Radiography is indicated if any concerns exist that deep structures are at risk (e.g., hand wounds, deep punctures, crushing bites, especially over joints)

Management

-

Debridement and removing devitalized tissue

- It is an effective means of preventing infection

-

Irrigation

- In general, 100 ml of irrigation solution per centimeter of wound is required with normal saline

-

Primary closure

- It may be considered in limited bite wounds that can be cleansed effectively (this excludes puncture wounds, i.e., cat bites)

- Other wounds are best treated by delayed primary closure

-

Facial wounds

- Because of the excellent blood supply, are at low risk for infection, even if closed primarily.

- The risk of infection must be discussed with the patient prior to closure

General management of bites

Fresh bite wounds without signs of infection do not need to be cultured

Infected bite wounds should be cultured to help guide future antibiotic therapy

Local public health authorities should be notified of all bites and may help with recommendations for rabies prophylaxis

Consider tetanus and rabies prophylaxis for all wounds

Antibiotic therapy

All human and animal bites should be treated with antibiotics.

The choice between oral and parenteral antimicrobial agents should be based on the severity of the wound and on the clinical status of the victim

Oral Amoxicillin–Clavulanate is an excellent choice for empirical oral therapy for human and animal bite injuries

Parenteral Ampicillin–Sulbactam is the drug of choice in severe cases

If patient is allergic to penicillin, clindamycin in combination with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole can be given

Antirabies treatment may be indicated for the following: If stray dog, not captured and dog not provoked prior to attack not captured, or known dogs found to have rabies within 10 days of bite, or any dog or animal proven to have rabies.

Snake Bites

Background

-

Most snakebites are non poisonous and are delivered by non poisonous species.

- North America is home to 25 species of poisonous snakes

- Characteristics of most poisonous snakes

- Triangular head

- Elliptical eyes

- Pit between the eyes and nose

- For example, rattlesnakes, cotton mouth and copperh eads

- Few snakes with round head are venomous, e.g., coral snakes (red on yellow bands)

Clinical presentation

-

Local manifestation

- Local swelling, pain, and paresthesias may be present

- Soft pitting edema that generally develops over 6–12 h but may start within 5 min

- Bullae

- Streaking

- Erythema or discoloration

- Contusions

-

Systemic toxicity

- Hypotension

- Petechiae, epistaxis, hemoptysis

- Paresthesias and dysesthesias—Forewarn neuromuscular blockade and respiratory distress (more common with coral snakes).

- The time elapsed since the bite is a necessary component of the history

- Determine history of prior exposure to antivenin or snakebite. (this increases risk and severity of anaphylaxis).

- Assessment of vital signs, airway, breathing, and circulation

Laboratory

CBC with differential and peripheral blood smear

Coagulations profile

Fibrinogen and split products

Blood chemistries, including electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine

Urinalysis for myoglobinuria

Arterial blood gas determinations and/or lactate level for patients with systemic symptoms

Radiography

Baseline chest radiograph in patients with pulmonary edema

Plain radiograph on bitten body part to rule out retained fang

Management

Prehospital care

Monitor vital signs and airway

Restrict activity and immobilize the affected area

Immediately transfer to definitive care

Do not give antivenin in the field

Indication for antivenom

Hemodynamic or respiratory instability

Abnormal coagulation studies

Neurotoxicity, e.g., paralysis of diaphragm

Evidence of local toxicity with progressive soft tissue swelling

Antivenom is relatively specific for snake species against which they designed to protect

There is no benefit to administer antivenom to unrelated species due to risk of anaphylaxis and expenses as well

Orthopedic consultation

Surgical assessment focuses on the injury site and concern for the development of compartment syndrome

Fasciotomy is indicated only for those patients with objective evidence of elevated compartment pressure

Bitten extremities should be marked proximal and distal to the bite and the circumference at this location should be monitored every 15 min to monitor for progressive edema and compartment syndrome

Black Widow Spider Bite

Background

Black spider with bright-red or orange abdomen

Neurotoxin acts at the presynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction, and decreased reuptake of acetylcholine and severe muscle cramping

Clinical presentation

Pricking sensation that fades almost immediately

Uncomfortable sensation in the bitten extremity and regional lymph node tenderness

A “target” or“ halo” lesion may appear at the bite site

Proximal muscle cramping, including pain in the back, chest, or abdomen, depending on the site of the bite

Dysautonomia that can include nausea, vomiting, malaise, sweating, hypertension , tachycardia, and a vague feeling of dysphoria

Management

-

Analgesics should be administered in doses sufficient to relieve all pain

- Oral medications may be tried for minor pain

- Intravenous opioid analgesics , such as morphine or meperidine, should be administered to all patients who are experiencing significant pain

- Benzodiazepines are adjunctive to the primary use of analgesics

Hydration and treatment of severe hypertension

-

Hypertension

- Frequently, adequate analgesia alleviates hyperten sion

- Dangerous hypertension is rare, but if it is present despite adequate analgesia, nitroprusside or antivenin should be considered

Brown Recluse Spider

Background

Dark, violin-shaped mark on the thorax

Venom causes significant local skin necrosis

Clinical presentation

Almost painless bite, and only rarely is a spider recovered

Erythema, itching, and swelling begin 1 to several hours after the bite

Central ischemic pallor to a blue/gray irregular macule to the development of a vesicle

The central area may necrose, forming an eschar

Induration of the surrounding tissue peaks at 48–96 h

Lymphadenopathy may be present

The entire lesion resolves slowly, often over weeks to months

Management

Tetanus status should be assessed and updated

Signs of cellulitis treated with an antibiotic that is active against skin flora

Treatment is directed at the symptoms

Scorpion Stings

Background

The only scorpion species of medical importance in the USA is the Arizona bark scorpion ( Centruroides Sculpturatus).

Toxins in its venom interfere with activation of sodium channels and enhance firing of axons.

Clinical presentation

Local pain is the most frequent symptom

Usually no local reaction

-

In small children

- Uncontrolled jerking movements of the extremities

- Peripheral muscle fasciculation, tongue fasciculation, facial twitching, and rapid disconjugate eye movements

- May misdiagnosed as experiencing seizures

-

Severe reaction

- Agitation

- Extreme tachycardia

- Salivation

- Respiratory distress

Management

Maintenance of a patent airway and mechanical ventilation in severe cases

-

Victims may be managed solely with supportive care:

- Analgesia and sedation

- Airway support and ventilation

- Supplemental oxygen administration

Antivenin therapy also may obviate or reduce the need for airway and ventilatory support

Status Epilepticus

Status epilepticus (SE) is defined as a seizure that lasts more than 30 min

Treatment of SE should be based on an institutional protocol, such as the following :

Management

-

Initial management

- Attend to the ABCs before starting any pharmacologic intervention

- Place patients in the lateral decubitus position to avoid aspiration of emesis and to prevent epiglottis closure over the glottis

- Make further adjustments of the head and neck if necessary to improve airway patency

- Immobilize the cervical spine if trauma is suspected

- Administer 100 % oxygen by facemask

- Assist ventilation and use artificial airways (e.g., endotracheal intubation) as needed

- Suction secretions and decompress the stomach with a nasogastric tube

- Carefully monitor vital signs, including blood pressure

- Carefully monitor the patient’s temperature, as hyperthermia may worsen brain damage

- In the first 5 min of seizure activity, before starting any medications, try to establish IV access and to obtain samples for laboratory tests and for seizure medications

- Infuse isotonic IV fluids plus glucose at a rate of 20 ml/kg/h (e.g., 200 ml D5NS over 1 h for a 10-kg child)

- In children younger than 6 years, use intraosseous (IO) infusion if IV access cannot be established within 5–10 min

-

Laboratory

- Finger stick blood glucose

- If serum glucose is low or cannot be measured, give children 2 ml/kg of 25 % glucose

- If the seizure fails to stop within 4–5 min, prompt administration of anticonvulsants may be indicated

- BMP and other lab depending on the history and physical examination

-

Anticonvulsant medication: Selection can be based on seizure duration as follows:

- 6–15 min: Lorazepam (0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV or IO slowly infused over 2–5 min); or diazepam per rectum at 0.5 mg/kg, not to exceed 10 mg

- 16–35 min: Phenytoin (Dilantin) or fosphenytoin (15–20 mg or PE/Kg max 1500 mg), not to exceed infusion rate of 1 mg/kg/min; do not dilute in D5 W; if unsuccessful, phenobarbital 15–20 mg/kg IV; increase infusion rate by 100 mg/min; phenobarbital may be used in infants before phenytoin

- 45–60 min: Pentobarbital anesthesia (patient already intubated); or midazolam, loading dose 0.1–0.3 mg/kg IV followed by continuous IV infusion at a rate of 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/h

- Pentobarbital anesthesia is administered as follows:

- Loading dose: 5–7 mg/kg IV

- May repeat 1-mg/kg to 5-mg/kg boluses until EEG exhibits burst suppression; closely monitor hemodynamics and support blood pressure as indicated

- Maintenance dose: 0.5–3 mg/kg/h IV; monitor EEG to keep burst suppression pattern at 2–8 bursts/min

- Other specific treatments may be indicated if the clinical evaluation identifies precipitants of the seizures. Selected agents and indications are as follows:

- Naloxone—0.1 mg/kg/dose, IV preferably (if needed may administer IM or SQ) for narcotic overdose

- Pyridoxine—50–100 mg IV/IM for possible dependency, deficiency, or isoniazid toxicity

- Antibiotics—If meningitis is strongly suspected, initiate treatment with antibiotics prior to CSF analysis or CNS imaging

Burns

First-degree burn

Superficial, dry, painful to touch, and heals in less than 1 week

Second-degree burn

Partial thickness and pink or possibly mottled red

Exhibits bullae or frank weeping on the surface

Usually is painful unless classified as deep and heals in 1–3 weeks

Second-degree burns commonly are caused by scald injuries and result from brief exposure to the heat source

Third-degree burn

It is the most serious

Pearly white, charred, hard, or parchment-like

Dead skin (eschar) is white, tan, brown, black, and occasionally red

Superficial vascular thrombosis can be observed

Electrical burns

Superficial burns can be associated with deep tissue injuries and complications

-

Complications of electric burns

- Cardiac arrhythmia

- Ventricular fibrillation

- Myocardial damage

- Myoglobinuria

- Renal failure

- Neurologic damage can develop up to 2 years following an electrical burn

- Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Transverse myelitis

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Paresis

- Paralysis

- Eye injuries

- Cataracts are the most common complications

- Fractures and joint dislocation can occur

Management

The superficial burn wound that extends to less than 10 % total body surface area (TBSA) usually can be treated on an outpatient basis unless abuse is suspected

-

Cotton gauze occlusive dressing to protect the damaged skin from bacterial contamination:

- Eliminate air movement over the wound (thus reducing pain)

- Decrease water loss

- Dressings are changed daily

-

Topical antimicrobial agent should be applied to the wound prior to the dressing for prophylaxis, e.g., silver sulfadiazine

- Silver sulfadiazine has activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus spp, and Candida albicans

- The primary adverse effect of silver sulfadiazine is leukopenia, which occurs in 5–15 % of treated patients

Application of various wound membrane dressings can promote healing with less painful wound dressing changes

Initial treatment of a child who has extensive burns

Fluid resuscitation to prevent shock

Early excision and grafting of the burn wound coupled with early nutrition support

Identification of airway involvement due to inhalation injury

Measures to treat sepsis

-

Fluid Administration

- Once the nature and extent of injury are assessed, fluid resuscitation is begun.

- Two large-bore intravenous catheters

-

Parkland Formula for fluid requirements

- ◦ 4 ml/kg/day for each percent of body surface area (BSA) burned

- The first half of the fluid load is infused over the first 8 h post-burn

- The remainder is infused over the ensuing 16 h

- The infusion rates should be adjusted to maintain a urine flow of 1 ml/kg per hour

- During the second 24 h, fluid administration is reduced 25–50 %

Resuscitation

ABCs

Stabilize airway, be sure it is patent

Place on oxygen, determine if patient requires assisted ventilations

Chest compressions if no heartbeat or if < 60 bpm (< 80 in infants and not increasing with ventilation)

IV fluids 20 ml/kg normal saline or lactated ringers

Shock

Goals—improve tissue perfusion, improve metabolic imbalance, restore end-organ function.

-

Types

- Hypovolemic—dehydration, blood loss

- Distributive—anaphylaxis, neurogenic, sepsis

- Cardiogenic—poor cardiac function

- Obstructive—cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax

-

Treatment

- Position—trendelenburg may be helpful

- Oxygen

- IV access

- Fluid resuscitation—20 ml/kg bolus crystalloid if not improving after 2–3 boluses consider packed red blood cells (PRBC) may use less fluid in cardiogenic shock

- Vasopressors if refractory to fluids

- Warm shock (septic)—norepinephrine

- Normotensive shock—dopamine

- Hypotensive shock—epinephrine

- Adrenal insufficiency—fluid refractory and pressor dependent shock should make you suspect adrenal insufficiency

- If suspected give hydrocortisone 2 mg/kg (100 mg max)

- Septic shock—antibiotics

- Anaphylaxis—epinephrine, diphenhydramine, H2 blockers and steroids

-

Monitoring

- Cardiopulmonary status

- Temperature

- Mental status

- Urine output

- Labs help with end-organ function assessment and for sepsis evaluation

Tachycardias with Pulse

-

Sinus—narrow complex, determine cause and treat accordingly

-

Causes 4 H’s and 4 T’s plus pain

- ◦ Hypoxemia, hypovolemia, hypothermia, hypo/hype rkalemia–metabolic

- ◦ Tension pneumothorax, tamponade, toxins, throm boembolism

-

-

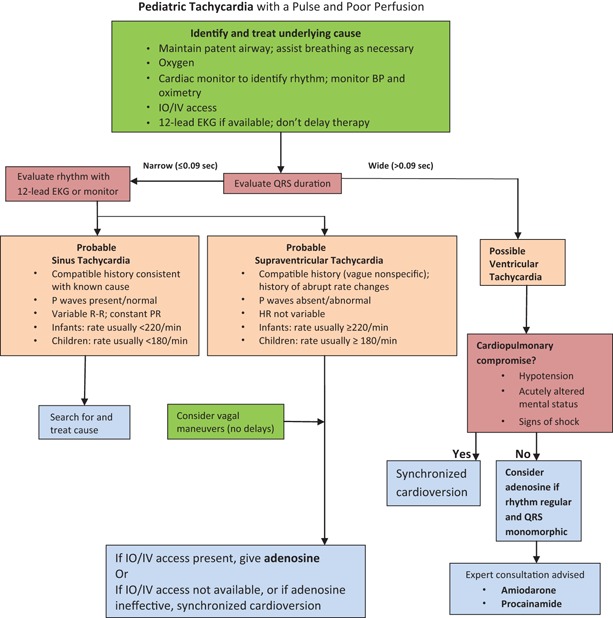

Supraventricular— > 220 infants and > 180 children, usually narrow complex, no p waves, consistent rate

- Adenosine if stable 0.1 mg/kg (6 mg max) if unsuccessful 0.2 mg/kg (12 mg max), rapid push

- Synchronized cardioversion if unstable 0.5–1 J/kg increase to 2 J/kg (Fig. 2)

-

Ventricular tachycardia—wide complex tachycardia—sharks tooth appearance

- Establish cause and treat if stable

- Synchronized cardioversion 0.5–1 J/kg if unsuccessful 2 J/kg

- Amiodarone 5 mg/kg, lidocaine and procainamide are other options

-

Torsades de pointes—ventricular tachycardia with oscillating amplitudes

- IV Magnesium 25–50 mg/kg (max 2 g) if cardiovascularly stable

- Defibrillation if unstable 2 J/kg increase to 4 J/kg if lower dose unsuccessful

Fig. 2.

Pediatric advance life support tachycardia algorithm. HR heart rate, IV intravenous, IO intraosseous, EKG electrocardiogram. (Kleinman ME et al. American Heart Association guideline for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care, part 14. Circulation 2010, 122, suppl. 3, pp. S876–S908, Fig. 3, p. S888)

Tachycardia without Pulse

-

Asystole—no electrical activity will look like flat line on monitor

- CPR and epinephrine 0.1 ml/kg (1:10,000)

-

Pulseless electrical activity (PEA)—may look like sinus tachycardia but with no pulse (no ventricular contractions)

- CPR and epinephrine 0.1 ml/kg (1:10,000)

-

Ventricular tachycardia (without pulse) or ventricular fibrillation

- CPR

- Defibrillate 2 J/kg increase to 4 J/kg if initial unsuccessful

- Add epinephrine after second defibrillation if unsuccessful

- Defibrillation followed by epinephrine each round every 3–5 min

- Amiodarone and lidocaine can be considered after epinephrine attempted

-

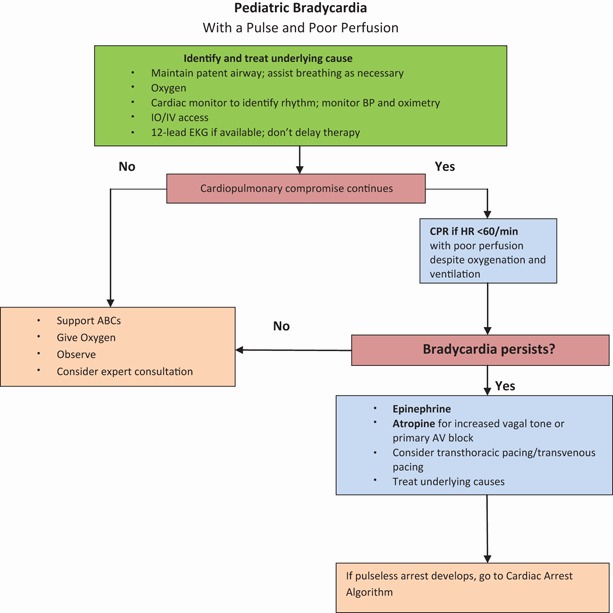

Bradycardia—most common pre-arrest rhythm in children with hypotension, hypoxemia and acidosis (Fig. 3)

-

Sinus bradycardia

- ◦ Maybe non-pathologic in case of well conditioned individuals like athletes

- ◦ Causes include: hypothermia, hypoglycemia , hypoxia, hypothyroidism, electrolyte imbalance, toxic ingestion, head injury with raised ICP

- ◦ Treatment—identify cause and treating that condition

- ◦ HR < 60 bpm in a child who is a well-ventilated patient, but showing poor perfusion, chest compression should be initiated

- ◦ If HR remains below 60 despite adequate ventilation and oxygenation, then epinephrine or atropine (0.02 mg/kg—0.1 mg min and 0.5 mg max) should be given

- ◦ Symptomatic bradycardia unchanged by above may require pacing

-

-

AV mode blocks

-

First degree—prolonged PR interval

- ◦ Generally asymptomatic

-

Second degree—2 types

-

◦ Type 1—Wenckebach

- ▪ Progressive PR prolongation until no QRS propagated

-

◦ Type 2—regular inhibition of impulse

- ▪ Usually every other P results in QRS

- Third degree—complete dissociation between P and QRS

-

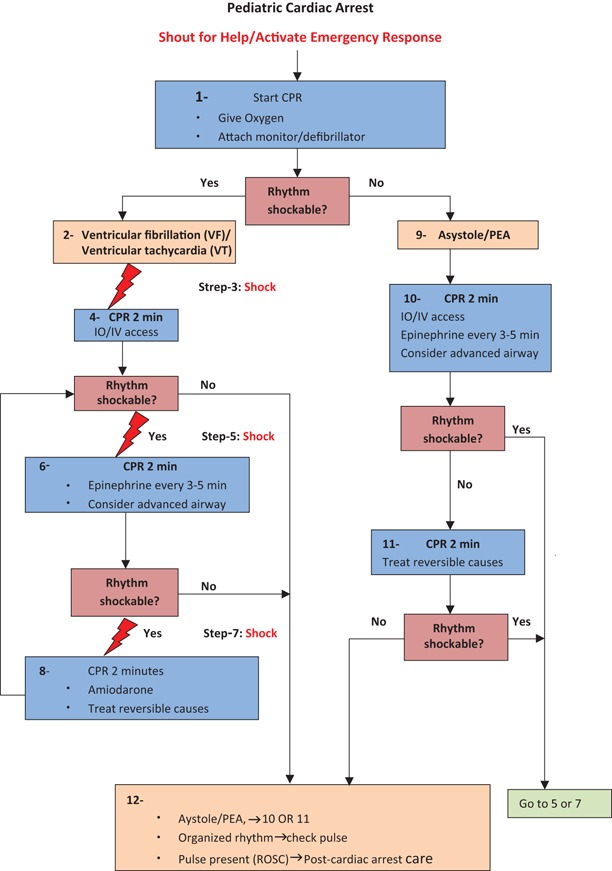

Reversible causes of cardiac arrest (Fig. 4)

- ◦ Hypovolemia

- ◦ Hypoxia

- ◦ Hydrogen ion (acidosis)

- ◦ Hypoglycemia

- ◦ Hypo-/hyperkalemia

- ◦ Tension pneumothorax

- ◦ Tamponade cardiac

- ◦ Toxins

- ◦ Thrombosis, pulmonary

- ◦ Thrombosis, coronary

-

-

Fig. 3.

Pediatric advance life support bradycardia algorithm. IV intravenous, IO intraosseous, ABCs airway, breathing, and circulation, AV atrioventricular (conductor), EKG electrocardiogram, HR heart rate, BP blood pressure, CPR cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. (Kleinman ME et al. American Heart Association guideline for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care, part 14. Circulation 2010, 122, suppl 3, pp. S876–S908, Fig. 2, p. S887)

Fig. 4.

Pediatric advance life support bradycardia algorithm. ROSC return of spontaneous circulation, IV intravenous, IO intraosseous, CPR cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. (Kleinman ME et al. American Heart Association guideline for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care, part 14. Circulation 2010, 122, suppl 3, pp. S876–S908, Fig. 1, p. S885)

Contributor Information

Osama Naga, Email: osamanaga@yahoo.com.

Steven L. Lanski, Email: steven1.lanski@tenethealth.com.

Osama Naga, Email: osama.naga@ttuhsc.edu.

Suggested Readings

- 1.Graeme KA. Toxic plant ingestions. Wilderness medicine. 5. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Donnell KA, Ewald MB. Poisoning. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, editors. Nelson Text book of pediatrics. 19. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 250–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wingert WA, Chan L. Rattlesnake bites in southern California and rationale for recommended treatment. West J Med. 1988;148:37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark RF, Kestner SW, Vance MV. Clinical presentation and treatment of black widow spider envenomation: a review of 163 cases. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:782–7. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright SW, Wrenn KD, Murray L, Seger D. Clinical presentation and outcome of brown recluse spiderbite. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:28–32. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(97)70106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curry SC, Vance MV, Ryan PJ. Envenomation by the scorpion Centruroides Sculpturatus. J ToxicolClinToxicol. 1984;21:417–49. doi: 10.3109/15563658308990433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epilepsy Foundation of America. ’. s Working Group on Status Epilepticus Treatment of convulsive status epilepticus. Recommendations of the Epilepsy Foundation of America’s Working Group on Status Epilepticus. JAMA. 1993;270:854–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510070076040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herndon DN. Total burn care. 2. London: Saunders; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols DG, Yaster M. Golden hour: handbook of pediatric advanced life support. St Louis: Mosby; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chameides L, Samson RA. Pediatric advanced life support. Dallas: American Heart Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]