Abstract

The first case of Influenza A (H1N1) in China was found in Hong Kong, on May 1st, 2009, where the patient had flown from Mexico to Hong Kong via Shanghai. On May 11th, Sichuan Province reported the first imported Influenza A (H1N1) case in mainland China, and the first domestic case was reported on May 29th.

Influenza A (H1N1) Epidemic in China: An Overview

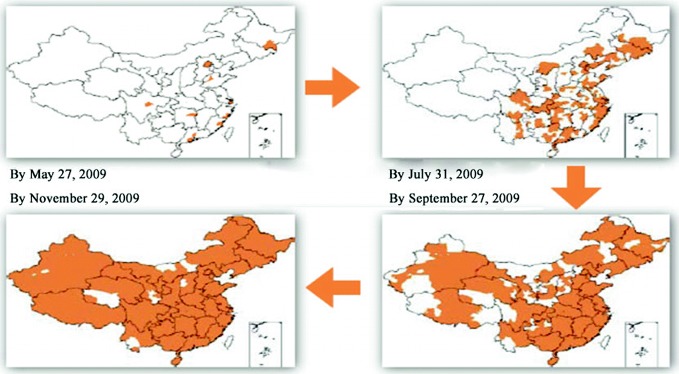

The first case of Influenza A (H1N1) in China was found in Hong Kong, on May 1st, 2009, where the patient had flown from Mexico to Hong Kong via Shanghai. On May 11th, Sichuan Province reported the first imported Influenza A (H1N1) case in mainland China, and the first domestic case was reported on May 29th. In June, the epidemic spread from eastern provinces where there are more airports and land ports to the inland provinces (Fig. 3.1). By mid-August, most cases were imported and virus activity level was low. Beginning in late August, the epidemic spread rapidly and widely, with increasing outbreaks especially in primary and secondary schools. Cases peaked at the end of November, after which the epidemic tapered off. From mid-January 2010, the Influenza A (H1N1) virus had a lower share in influenza cases than Influenza B viruses. Beginning in April, Influenza A (H1N1) activity remained low, and there were fewer influenza outbreaks than in the same period of previous years. On August 10th, the WHO announced the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic had moved into the post-pandemic period, which meant that global influenza activity—including Influenza A (H1N1)—had returned to normal seasonal levels.

Fig. 3.1.

Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Circulation in mainland China.

Source of data Influenza A (H1N1) prevention and control (Special Issue on the 2010 Plenary Sessions of the National People’s Congress and the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference)

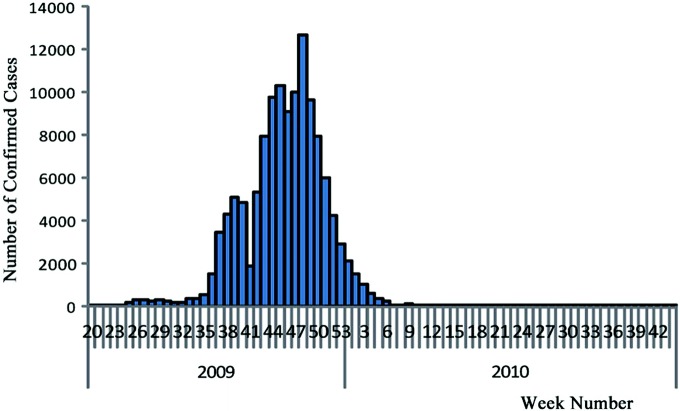

Time Distribution for Confirmed Cases of Influenza A (H1N1)

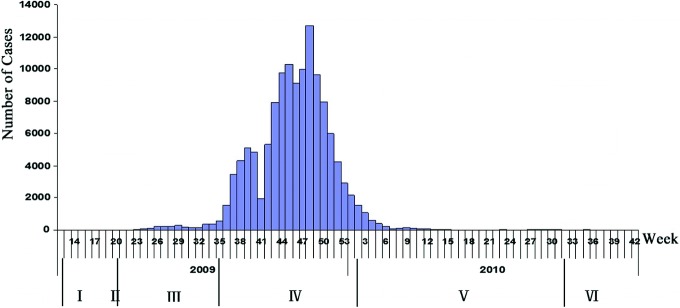

By 24:00 p.m., August 29th, 2010, the national Influenza A (H1N1) information management system showed that a total of 128,080 confirmed cases had been reported across the country (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan; the same below), including 8349 severely ill cases (2785 critically ill) and 805 fatalities. Admittedly, however, due to a variety of factors such as the limitations of the monitoring system, the accessibility of health care resources, the public’s medical behaviors, specimen collecting and testing policies, and the limitations due to sensitivity and specificity of laboratory tests, confirmed cases in any country—including China—were much lower than the number of actually infected cases. The number of confirmed cases reported nationwide reached its peak (12,719) in the 48th week of 2009, and dropped rapidly afterwards. From the 14th through the 34th week of 2010 (from April 5th to August 29th), except for the 31st week during which 53 cases were reported, there were no more than 30 cases reported weekly (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.2.

Time distribution of confirmed cases in mainland China.

Source of data Influenza monitoring weekly, 34th week, 2010

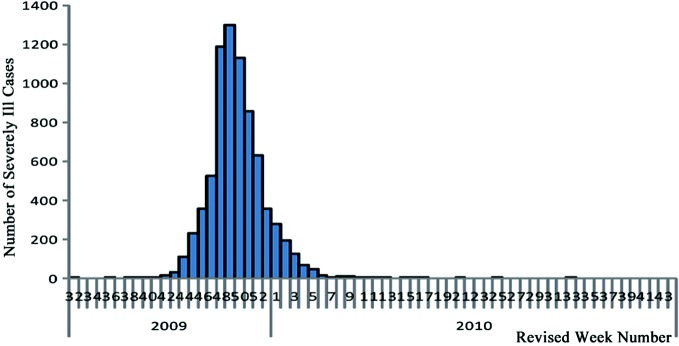

The first severely ill case in mainland China was reported in Guangdong on August 8th, 2009, and thereafter severely and critically ill cases were on the rise. After reaching its peak (1297) in the 49th week (December 6th) of 2009, the number of severely ill cases reported dropped. Beginning in the 4th week (January 31st) of 2010, the number of weekly severely ill cases reported fell below 100; from the 12th to the 17th week (March 22nd–May 2nd), except for the 14th week during which no severely ill cases were reported, the weekly number of severely ill cases reported was between one and seven; from the 18th to the 34th week (May 3rd–August 29th), no severely ill cases were reported except for the 21st, the 25th, and the 33rd week where one case was reported for each week (Fig. 3.3).

Fig. 3.3.

Time distribution of severely Ill cases in Mainland China.

Source of data Influenza monitoring weekly, 34th week, 2010

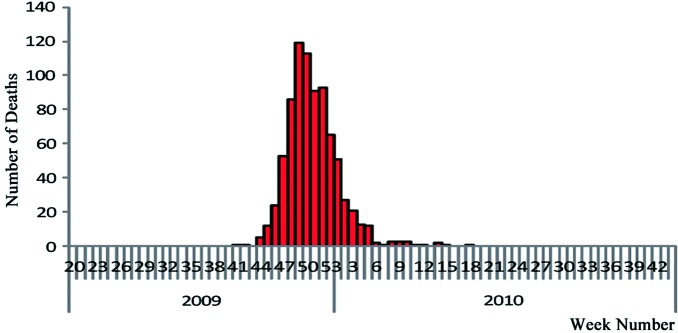

On October 4th, 2009, the first fatal case from Influenza A (H1N1) in mainland China was reported in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Reported fatalities peaked (at 119) in the 49th week (December 6th) of 2009 and tapered off thereafter. Beginning in the 6th week of 2010, fatalities reported were sporadic, ranging from zero to three cases per week. From the 19th week (May 16th) onwards, no fatalities were reported in the country for 16 consecutive weeks (Fig. 3.4).

Fig. 3.4.

Time distribution of fatalities in mainland China.

Source of data Influenza monitoring weekly, 34th week, 2010

Age Distribution for Confirmed Cases

From the 18th week (May 3rd–9th) to the 53rd week (December 27th–31st) of 2009, a total of 118,096 laboratory confirmed cases were reported in China, over 90% of the patients aged between five and sixty-four years old. The age groups <5, 5–14, 15–64, and ≥65 accounted for 5.4, 42, 52, and 0.88% of the total confirmed cases.

Influenza A (H1N1) Fatality Rates

From the 18th to the 53rd week of 2009, the Influenza A (H1N1) epidemic in China had a case fatality rate (CFR) of 0.5%, which may have been overestimated as it was calculated by dividing the number of reported confirmed cases by the number of confirmed deaths. CFRs in this period for the age groups of <5, 5–14, 15–64, and ≥65 were 0.9, 0.1, 0.7, and 5.6%, respectively.

China’s Response Strategies and Readjustments

At the end of April 2009, facing grim, complex situations in the wake of the global financial crisis and the outbreaks of Influenza A (H1N1), the Chinese government adopted the response principles and strategies of “focusing on, respond actively to, and coping with the epidemic scientifically and according to law through joint prevention and control mechanisms.” Thereafter, specific prevention and control strategies were adopted and readjustments made appropriately in line with the different epidemic phases.

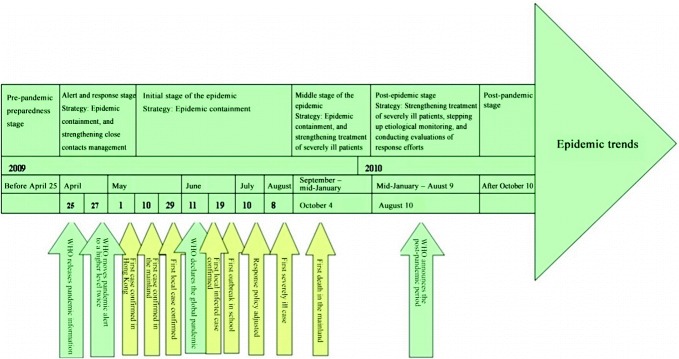

China’s Influenza A (H1N1) prevention and control efforts can roughly be divided into six stages. Stage I, which occurred before April 25th, 2009 is characterized by pre-pandemic preparedness efforts. In Stage II, which lasted from April 25th to May 10th, 2009, alerts were issued and responses made, with the main strategies of containing imported cases and strengthening close contacts management. In Stage III, the initial epidemic stage which lasted from May 10th to August 30th, 2009, the response strategy was epidemic containment with anti-proliferation prevention and control measures. In Stage IV, the middle stage of the epidemic which lasted from September 2009 to mid-January 2010, local cases rose rapidly and the response strategy centered on epidemic containment and the strengthened treatment of severely ill patients. In Stage V, the post-epidemic stage which lasted from mid-January to August 9th, 2010, the number of cases fell rapidly, and the response strategy then focused on strengthening treatment of severely ill patients and stepping up etiological monitoring; evaluations on response efforts were conducted at this time. Stage VI began on August 10th, 2010, when the WHO announced the beginning of the post-pandemic period; in this stage, considering the reality of the epidemic, China readjusted its influenza monitoring strategy, optimized its influenza monitoring network, and improved overall monitoring quality (Figs. 3.5 and 3.6).

Fig. 3.5.

Stages of Influenza A (H1N1) epidemic in China

Fig. 3.6.

Key epidemic developments in China

Pre-pandemic Preparedness Stage (Before April 25th, 2009)

After the 2003 SARS epidemic, China’s public health service experienced rapid development, with a great amount of work done on influenza pandemic prevention and preparedness. On the one hand, the government boosted public health development by making large improvements to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) and the construction of its monitoring system, strengthening field epidemiology training, developing contingency plans for public health emergencies, bolstering the leading role of the government in public health, and increasing epidemic information openness and transparency. On the other hand, pandemic preparedness efforts also became centered on contingency planning, and emergency prevention and response to the Avian Influenza, including the reinforcement of the influenza monitoring network, and the preparations to increase production capacity and materials for vaccines and antiviral drugs.

China CDC Construction and Monitoring System Development

In November 2003, the National Center for Disease Data Monitoring was built at China CDC, and on January 1st, 2004, the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention was completed. In 2006, the MOH announced the completion of a public health information direct reporting network system. By the end of December 2008, centers for disease control and prevention (CDCs) in all regions of the country, 97% of county level and above health care institutions, and 82% of township-level health care centers were all able to report online infectious disease outbreaks and public health emergencies, which marked the completion of a basic public health emergency monitoring and reporting system. This newly constructed influenza monitoring network covered the entire country, and 63 network laboratories and 197 sentinel hospitals (including 31 rural sentinel points) were completed. Figure 3.7 shows the network structure.

Fig. 3.7.

Structure of China’s influenza monitoring network

Preparedness for Pandemic Contingency Plans

During the 2003 SARS epidemic, the State Council urgently formulated and implemented the Public Health Emergency Response Regulations. In February 2004, it formulated and issued the National Response Plan for the Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, and in 2005 issued the National General Response Plan for Public Health Emergencies along with two specific emergency response plans—the Public Health Emergency Response Plan and the National Health Emergency Plan for Public Emergencies. On September 28th, 2005, the MOH promulgated the Influenza Pandemic Preparedness and Response Plan of the Ministry of Health (Tentative), based on the WHO Global Influenza Preparedness Plan, which outlined, among other things, the organization and leadership system, duties, preparedness, emergency response, and supervision for influenza pandemics. Using this plan as its foundation, the MOH soon afterwards issued two special-purpose guidance books to local health departments, the Manual for Implementation of the Influenza Pandemic Preparedness and Response Plan of the Ministry of Health (Tentative), and the Publicity Manual on the Influenza Pandemic Preparedness and Response Plan of the Ministry of Health (Tentative). Also, the MOH developed sector-specific contingency plans in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA), the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) and evaluated its 2005 influenza pandemic preparedness and response plan. The MOH also formulated the Plan for Monitoring, Prevention and Control in Different Phases of an Influenza Pandemic, and inspected the national health care system’s response capabilities. Therefore, from the perspective of contingency planning, China had basically built an emergency response system consisting of overall planning, special-purpose planning, sector-targeted planning and single event planning.

Capacity Building and Preparation

Strengthened Emergency Response Teams

In regards to emergency response teams, 32 national-level specialized public health emergency management teams and anti-terrorism health emergency response teams, roughly 300 people under 6 categories, were established. At the provincial, prefectural, and county levels, health emergency response teams were also formed consisting of healthcare and disease prevention and control personnel.

Established an Expert Group

In 2004, the MOH Expert Group for Influenza Prevention and Treatment was established, and was charged with the following responsibilities: providing technical guidance, training, and supervision for national influenza monitoring; directing onsite response efforts to epidemic outbreaks; drafting national technical plans and documents; providing supervisory guidance for health departments and disease control and prevention departments at all levels; providing advice and recommendations on national response plans for influenza pandemics; and offering technical consultations on national influenza prevention and control efforts.

Strengthened Training

In October 2001, the MOH and China CDC launched a two-year Chinese Field Epidemiology Training Program (CFETP) course under the support of such international organizations as the WHO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), as well as domestic and foreign parties. By April 2009, this program had recruited 100 people from national, provincial, and municipal disease control and prevention institutions and health supervision agencies, 68 of whom had graduated top in their class. These professionals were groomed for China’s public health industry with the skills to solve a myriad of acute, difficult, and dangerous public health emergencies. With all eyes on the possible outbreak of a pandemic, China followed suit and placed pandemic preparedness at the top of its national agenda. An important part of influenza pandemic preparedness is that when a pandemic occurs, there must be adequate and effective resource management for treating large numbers of severely ill patients in a short period of time. Employing the Flu Surge Model which was developed by the United States CDC, CEETP students discovered that in the case of an influenza pandemic, Beijing could face severe shortages of important resources like intensive care units (ICUs) and respirators, an evaluation result which was immediately reported to the Beijing government and attracted a lot of attention from related departments. At the same time, the MOH and the China CDC organized yearly national training courses on influenza epidemiology and laboratory monitoring technology; in 2007, three such training courses were held for 307 people. Key provincial laboratories also carried out hands-on training, where 10 professionals in networked laboratories received training. In 2007–2008, the MOH Office of Health Emergency provided prefectural and municipal health officials across the country with four rounds of special training in health emergency management, including risk preparedness and pandemic response.

Supported Capacity Building for National Influenza Centers

In 2005, the China CDC established an influenza pandemic preparedness and response technical group, which was responsible for monitoring global and domestic pandemic trends. The Chinese National Influenza Center (CNIC) was established in 1957 to provide technical support for national influenza prevention and control efforts. The CNIC joined the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network in 1981 and since then has provided the WHO with isolated influenza strains each year, because of this China has been recognized worldwide for being an integral part in providing material for potential influenza vaccines. In early 2007, WHO experts conducted an onsite assessment of the CNIC. In early 2008, the MOH submitted an official application to the WHO for designating the CNIC as a WHO Collaborating Center for reference and research on influenza and on November 1st, 2008, the CNIC began a trial period for it.

Vaccine and Antiviral Preparedness

Vaccine and antiviral preparedness included revising the China Guidelines on Influenza Vaccination, expanding the usage of vaccinations against seasonal influenza, boosting vaccination capacity, encouraging all localities to formulate preferential policies, and lastly expanding coverage ofvaccinations against seasonal influenza.

In 2008, with the support of the WHO and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the China CDC conducted a national survey of seasonal influenza vaccine production and usage, which provided background information and helped the country formulate strategies for the application of seasonal influenza and pandemic vaccines.

In April 2008, a pre-pandemic vaccine against the H5N1 virus was approved by the China Food and Drug Administration (SFDA), and the government invested capital and ensured an annual production capacity of roughly 20 million doses. If the pandemic strain was H5, then vaccines could be produced within three months, and if the strain mutated, it would take six months in total from strain separation to vaccine production. In regards to antiviral preparedness, in addition to a national Tamiflu stockpile of 500,000 doses and a local Tamiflu stockpile of 37,900 doses, production from two Chinese manufacturers—with an annual capacity of about 15 million courses of treatment, and a production cycle of about 3 months (which Roche licensed to produce Tamiflu) were incorporated into the country’s strategic stockpile for influenza pandemics. The China CDC stockpiled 20,000 doses of the vaccine for avian influenza control.

International and Regional Collaboration

China signed the 2005–2010 Influenza Monitoring Collaboration Program with the WHO, and the China-U.S. Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Disease Program with the United States. At the same time, China advocated establishing a ASEAN “10+3” Infectious Disease Information Communication Mechanism, which provided ASEAN countries with training in laboratory monitoring of influenza, and collaboration between Japan, South Korea, and Australia occurred through the development of pandemic response tabletop exercises.

The Alert and Response Stage (April 25th–May 10th)

In light of the country’s actual pandemic trends, the Chinese government in this phase adopted the strategy of “containing the importation of Influenza A (H1N1) and strengthening management of close contact with infected patients.” The purpose of this strategy was to “buy more time for pandemic response by preventing cross-border transmission, delaying the rate of transmission, lowering the peak of transmission, and mitigating the harmful impact per unit of time.”

Policy Background

On April 25th, 2009, the WHO held the first Emergency Committee Meeting, declaring that the swine flu outbreaks in Mexico and the United States had constituted a “public health emergency of international concern,” and recommended that all countries strengthen monitoring and alert concerning irregular outbreaks of flu-like diseases and serious pneumonia. On April 27th, 2009, the WHO elevated the pandemic alert from Phase 3 to Phase 4, and again to Phase 5 on April 29th. The WHO advised that all countries immediately launch their response mechanisms as per pandemic emergency response plans and to take the following effective measures: strengthen surveillance, detect and treat cases as soon as possible, and actively treat and control nosocomial infections, all of which would help prevent the outbreak and spread of the pandemic. The fact alone that the alert levels increased twice in three days indicated the urgency and severity of the pandemic situation.

Main Response Measures

Established the “8+1” Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism

On April 30th, 2009, China established a multi-departmental joint prevention and control mechanism headed by the MOH. Under this mechanism, 33 departments (which later increased to 38) and institutions constituted 8 work groups—general, port, healthcare, support, dissemination and communication, foreign collaboration, science and technology, and animal husbandry and veterinary—and an expert committee on the prevention and control of Influenza A (H1N1), forming an “8+1” structure for joint prevention and control efforts. Roles and standard operating procedures were defined for the joint prevention and control mechanism, the work groups, and the expert committee. A plenary and liaison meeting system was also established. Problems which a work group encountered would in principle be solved by the work group itself, and those which the work group found difficult to solve would be settled through coordination under the joint prevention and control mechanism—general affairs would be solved by regular liaison meetings, and major issues decided by plenary meetings.

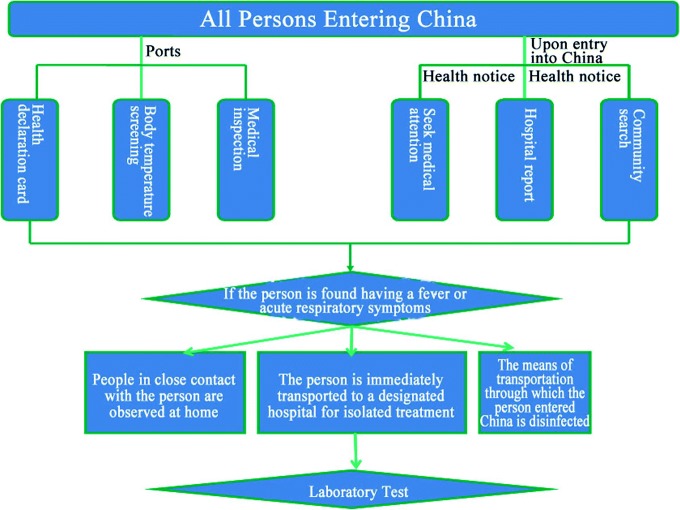

Strengthened Entry-Exit Inspections and Quarantine and the Management of Close Contact with Infected Patients

On April 30th, 2009, after the No. 8 Proclamation issued by the MOH, the Chinese government incorporated Influenza A (H1N1) into Category B infectious diseases under the Law on Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, adopted prevention and control measures of Class A infectious diseases, and incorporated them into the Frontier Health and Quarantine Infectious Disease Management as stipulated in the Frontier Health and Quarantine Law of the People’s Republic of China. The principle measures adopted included the following: ports executed a strict health declaration card system, body temperature screening, and medical inspection systems; professionals were dispatched to inform those who had entered China that they must seek medical attention and report to the related government department when having flu-like symptoms; and disease control and prevention institutions searched communities for those in close contact with infected patients, isolated them, and kept them under observation. Investigations were conducted on the places and people related to those in close contact with the virus, and effective prevention and control measures were taken for those with fever and other symptoms. Designated hospitals were prepared to receive and treat influenza patients (See Fig. 3.8 for specific measures and procedures).

Fig. 3.8.

Detection measures for traveling into China

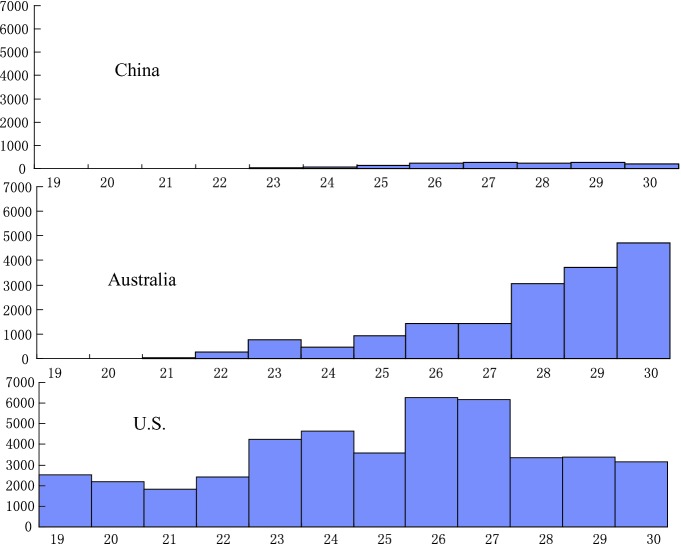

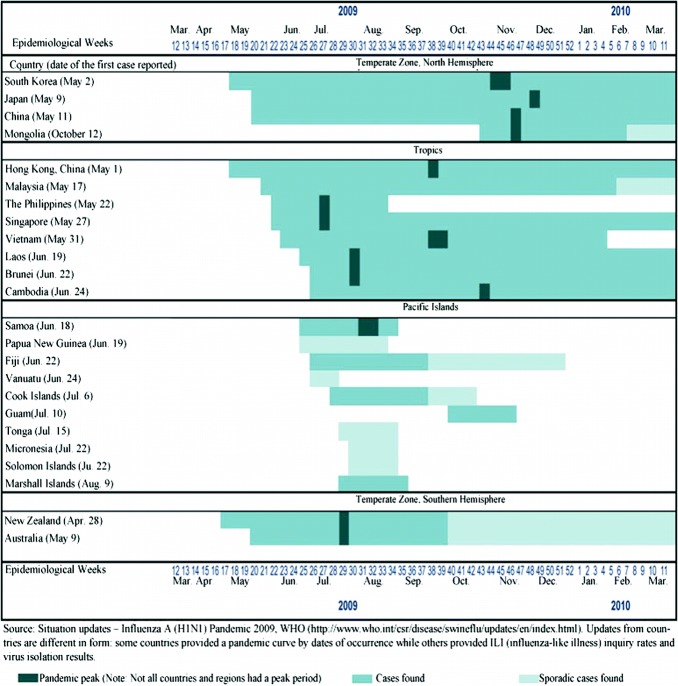

As shown by the epidemiological curve of reported cases in China (Fig. 3.1), cases didn’t spike until well over three months after the emergence of the first case, the peak remained at a relatively low level, and compared with other countries, the pandemic curve of this stage for the country was relatively flat (Fig. 3.9). This evinces that the country’s early containment strategy did in fact reach its goal of “delaying the pandemic’s transmission rate.” According to the WHO’s analysis of data on thirteen countries and territories in the Western Pacific, the median interval between the time the first confirmed case and the pandemic peak was 13 weeks (the average was 16 weeks), with Laos having the shortest interval (7 weeks) and China and Japan having the longest interval (30 weeks) (Fig. 3.10). This also suggests that China’s early “containment strategy” was effective and provided more time for response preparation and efforts.

Fig. 3.9.

Distribution of reported cases of Influenza A (H1N1) in China, the United States, and Australia from the 19th to 30th week of 2009

Fig. 3.10.

Peak dates of laboratory-confirmed cases reported to the WHO by Western Pacific countries and territories in the first year of the Influenza A (H1N1) Pandemic

Strengthened Virus Monitoring and Conducted Thorough Investigations

In order to keep up to date on epidemic trends and monitor possible mutations of the virus in the wake of the outbreak, China invested nearly 400 million RMB on testing large amounts of specimens and expanding the influenza monitoring network to include 411 influenza monitoring laboratories and 556 sentinel hospitals—a network which covered all prefectural-level cities and some priority districts and counties. All of these facilities were required to begin operation in September.

The China CDC provided technical support and services for national response efforts. These services included the following: upgrading the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention; incorporating Influenza A (H1N1) into the Disease Monitoring Information Reporting Management System, the China Influenza Monitoring Information System, and the Public Health Emergency Information System; specifically establishing an Influenza A (H1N1) information management system; tracking and analyzing domestic influenza epidemic trends through the National Infectious Disease Network Reporting System and the National Influenza Monitoring Network System; collecting and analyzing information on the condition, treatment and outcome of Influenza A (H1N1) cases; providing analysis reports and information support needed to improve prevention and control strategies and measures; mapping global epidemic distribution and the distribution of isolated personnel by provinces; integrating individual cases and community outbreaks into the national infectious disease and public health emergency information systems for direct online reporting; enabling timely submission of questionnaires, statistical, and analytical reports on severely ill cases; monitoring domestic and foreign epidemic information; optimizing information systems and platforms; ensuring the collection and analysis of information on mass vaccination; and monitoring any side effects of the vaccination.

The country’s proactive efforts in the alert and response phase of this influenza pandemic are in stark contrast to the 2003 SARS outbreak where the epidemic was not clearly defined and there was a lack of information. The development of the national disease monitoring system and the capacity of the CDCs withstood this epidemic, which points to the rapid progress made in recent years in national public health emergency system and capacity building.

Nevertheless, the national prevention and control efforts for this pandemic also revealed some unusual phenomena; for instance, provinces with the best performance in combating the pandemic reported the most cases, but those provinces which reported the fewest number of cases were not necessarily performing up to par in the response efforts.

Initiated Research and Development of Diagnostic Reagents and Antiviral Drugs

Upon learning about the Influenza A (H1N1) outbreak in Mexico, as per instructions, the CNIC immediately began the development of testing kits. On April 27th, the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention (IVDC) of the China CDC, obtained information on genetic sequences of the Influenza A virus from the U.S. CDC and immediately engaged in sequence alignments and the design and testing of nucleic acid detection techniques. On April 29th, after receiving information on the primer of nucleic acid detection from the WHO, the IVDC promptly compared a variety of seasonal Influenza A (H1N1) viruses, synthesized the primer sequence needed for detection, and prepared the first-generation nucleic acid detection reagent for the human Influenza A virus—which was distributed to 84 influenza monitoring laboratories across the country on the night of April 30th. On May 1st, the first round of training for influenza monitoring laboratories, especially those in port cities, began. Also, through the WHO, the CNIC provided 12 countries including Cuba, Mongolia, and Vietnam as well as Macao with the test kit that China had independently developed. Test kits were swiftly deployed to monitoring network laboratories throughout the country, and training was promptly carried out for test professionals. Because China had strengthened capacity building for the CNIC in the aftermath of the SARS epidemic, the CNIC was strong enough to play a crucial role in the national response to the Influenza A (H1N1) Pandemic, earning it international recognition in the process.

Developed Communication and Collaboration with Foreign Countries, Collected Information on the Pandemic Abroad, and Made Every Effort to Handle Foreign-Related Prevention and Control Affairs

In the early days of the pandemic, in order to stay up to date on latest trends, the MOH was proactive in contacting the WHO and the disease control departments of other affected countries. At the earliest possible time, it obtained strains isolated in the United States and Mexico for test kit research and development purposes, and also helped Chinese vaccine manufacturers obtain seed strains from the WHO for vaccination development. Also, through the WHO, the CNIC provided 12 countries including Cuba, Mongolia, and Vietnam as well as Macao with the test kit that China had independently developed. It is evident that as countries became more interdependent in the wake of economic globalization, prevention and control efforts against infectious diseases required the attention, participation, and collaboration of all countries involved. Facing the challenge of preventing and controlling an influenza pandemic, China actively pursued international collaboration and promoted the implementation of prevention and control strategies, the collaboration in rapid information sharing, and extensive international exchanges, all in order to improve capacity building for emergency response teams so that everyone could enjoy the benefits of information sharing.

Conducted Response Preparations and Increased Emergency Material Stockpiles

On April 29th, 2009, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) jointly and urgently established an important coordination mechanism of emergency material support with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) along with the Ministry of Finance (MOF), Ministry of Commerce (MOC), Ministry of Health (MOH) and China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA). On that same day, the NDRC made a request to the MIIT Department of Consumer Goods Industry to increase national health emergency stockpiles of clinical treatment materials and epidemic materials needed to respond to the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. On April 30th, a support group headed by the NDRC was established under the joint prevention and control mechanism. In early May, the central government provided 5 billion RMB and local governments appropriated capital as well to guarantee adequate funds for national response efforts. However, at this time it was also discovered that there had been a serious shortage of emergency material reserves in the past, which exposed the weaknesses of health emergency management.

Disseminated Prevention Awareness and Carried Out Health Education Campaigns

In the early days of the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, the MOH’s related departments and agencies established an expert advisory mechanism which included experts in public health, disease control and prevention, and emergency management, to meet the huge public demand for knowledge about the epidemic; media interviews were arranged with these experts in order to promulgate needed information. Central and local websites were upgraded on the subject of influenza. The 12320 Health Hotline, the MOH website, the Chinese Center of Health Education website, and other public health services provided channels for direct communication, and online interviews were conducted through Xinhuanet and China.org.cn to better reach the general public. Provincial-level spokesmen were appointed to release public health information as needed. The health campaigns were different this time around, as they published more specific content than just statistical data, including the addition of expert analysis, public health recommendations, and risk communication strategies that were continually being updated—these elements were never presented in previous disease prevention and control efforts. For example, during the peak period of Chinese students returning home from abroad, health experts wrote them a six-point recommendation letter advising them to protect themselves and others, and this proved to be quite an effective means of information dissemination. Governments at various levels, schools and some other institutions adopted also similar communication and education methods. Practice has proved that effective risk communication, trust in the government, and reliable information help to mitigate social and economic losses caused by public anxiety and worry.

Initial Stage of the Epidemic (May 10th–August 30th, 2009)

Most of the cases reported in this phase were imported, and the strategy adopted focused on “equal importance for containment and prevention, with the goal of lowering transmission peaks.”

Policy Background

On the afternoon of May 10th, 2009, the MOH suddenly received a report from the Provincial Department of Health of Sichuan stating that Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital had treated a patient who was preliminarily diagnosed as a suspected Influenza A (H1N1) case based on clinical symptoms and laboratory test results. On the night of May 10th, the MOH declared the first suspected Influenza A (H1N1) case found in mainland China. Tests conducted afterwards by the China CDC and the Academy of Military Medical Sciences proved that it was in fact China’s first case. On May 11th, the MOH declared it to be the first confirmed Influenza A (H1N1) case. Imported cases emerged in Shandong and Beijing soon afterwards.

On June 11th, 2009, the WHO declared the highest level of pandemic alert, i.e. Phase 6, which meant that the human-to-human spread of the virus was occurring in many other countries and regions outside North America. This was the WHO’s first ever declaration of a global influenza pandemic in more than 40 years.

On June 11th, the first local case from unknown sources of infection emerged in China, suggesting that prevention and control efforts should be focused on curbing the domestic spread of the virus and its transmission in schools and communities.

On June 19th, the first Influenza A (H1N1) outbreak in a school was reported in Dongguan, Guangdong. From late June to early July, outbreaks continued to rise across the country. In light of the pandemic trends and Hong Kong’s experience in strategic policy adjustment, the State Council held an executive meeting on July 3rd, at which discussions and arrangements were made to adjust and improve prevention and control measures, and duties and tasks were allocated. During the summer holidays, outbreaks occurred among attendees of summer camps in some provinces, putting the Chinese government on full alert at that time.

The country’s first critically ill case was reported on August 8th. Thereafter, among new confirmed cases, imported cases were gradually overtaken by locally infected cases.

Main Response Measures

Building upon the previous phase, these measures included the following: strengthening the tracking and management of close contacts; ensuring designated hospitals treat patients; stepping up nosocomial infection control; expanding the network of pandemic monitoring sentinel hospitals and laboratories; strengthening and improving information collection and reporting; strengthening clinical case monitoring and epidemiological monitoring; implementing emergency research projects; accelerating vaccine development; adjusting and improving port quarantine and inspection measures; improving prevention and control plans by enhancing capacities for treatment of critically ill patients; bolstering prevention and control efforts in schools, communities, towns, hospitals, public places and other priority places; strengthening risk communication; and guiding public opinion. Specific measures were as follows:

Gradually Strengthened Strict Management of Close Contacts, and Modified Management Policy When Needed

Very strict management measures regarding close contacts were adopted in the pandemic’s initial phase, and adjustments were made accordingly based on epidemic analysis. For example, from April 25th to June 20th, 2009, according to the Influenza A (H1N1) Port Health and Quarantine Procedure and Operational Specifications, close contacts were defined as passengers of the row where the patient with Influenza A (H1N1) was seated and of three rows immediately behind and in front of the patient in an airliner, or passengers inside the same ship cabin or railway carriage (including attendants that served the patient). After June 20th, the Notice on Adjustments to the Influenza A (H1N1) Port Health and Quarantine Procedure and Operational Specifications re-defined close contacts as including one passenger on each side of the patient, and three passengers of three rows both immediately behind and/or in front of the patient.

On July 8th, the MOH issued the Notice of the MOH General Office on Further Improving Influenza A (H1N1) Prevention and Control Measures (No. 122, 2009), which became an important turning point in the policy adjustment on Influenza A (H1N1) prevention and control. The notification discontinued the need for closer medical observation of close contacts and implemented home medical observation or follow-ups by the health authorities. According to survey results, per capita costs for tracking and concentrated observation of close contacts amounted to 5218.50 RMB, while it only cost 270.80 RMB on average to track and observe a close contact at home. The policy adjustment was instrumental in lowering social costs and avoiding an excess prevention and control measures.

Pushing Designated Hospitals into Motion, Actively Treated Patients, and Strengthened Nosocomial Infection Control

On April 27th, 2009, the MOH issued a document requiring local health departments at various levels to designate hospitals to receive and treat Influenza A (H1N1) cases. Provinces across the country then forwarded this document and made arrangements accordingly. From June 11th to early August 2009, though cases were largely imported ones, local mildly ill cases gradually increased. China reported its first severely ill case on August 8th, and the success in curing it paved the way for treatment of the many more severely and critically ill cases that came later on. The strict policies adopted in the three months from the first confirmed domestic case to the first severely ill case bought ample time for proper treatment preparation. As it became known that designated hospitals were not equipped to meet the needs of curing severely ill cases, as they lacked mechanical ventilators, ICUs and related technicians, local governments began incorporating general hospitals with decent intensive care facilities into their lists of reserve hospitals in preparation of treating severely ill patients.

Expanded Network of Influenza Monitoring Sentinel Hospitals and Laboratories

On May 20th, the MOH decided to convert 119 laboratories across the country into national influenza monitoring network laboratories, and 167 hospitals as national influenza monitoring sentinel hospitals. The MOH required that the added healthcare institutions begin monitoring Influenza A (H1N1) starting on that very day, and the China CDC immediately began organizing personnel training for these institutions, as well as distributing test kits among the added network laboratories. Monitoring standardization and quality control also began immediately. By mid-June, there were a total of 566 influenza monitoring sentinel hospitals and 411 network laboratories in the country, and the China CDC mobilized staff to train teachers for these new monitoring network units.

Launched Emergency Research Projects and Promoted Vaccine Development

In early June 2009, an Influenza A (H1N1) vaccine development and production coordination mechanism was established consisting of the NDRC, the MOH, the MIIT, the CFDA, the China CDC, the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Product (NICPBP), and ten influenza vaccine manufacturers. During vaccine development, an alternative approach was employed in preparing the standard materials, and a quantitative testing method for vaccine antigens was created which shortened the time needed for vaccine development by one month. With established seasonal influenza vaccine production processes, the vaccine manufacturers successfully produced an Influenza A (H1N1) vaccine for clinical trials. The CFDA opened up a channel for fast-track approval of the vaccine to ensure qualified vaccines against the virus could be used for clinical trials with enough time to stay relevant. From July 22nd to September 18th, 2009, large-scale clinical trials were conducted simultaneously with 13,000 volunteers in seven regions of the country.

Made Timely Adjustments to Response Policies, Distributed Community-Level Outbreak Control Plans and Mildly Ill Cases Management Plans, and Categorized Influenza A (H1N1) Under Category B for Infectious Disease Management

To curb community-level outbreaks and implement scientific prevention and control measures, on June 11th the MOH issued the Work Plan for Control of Community-level Influenza A Outbreaks (Tentative), providing efficient and effective guidance for the country to engage in disease prevention and control efforts. The timely introduction of this plan paved the way for coping with possible community-level outbreaks. In the plan, in light of expert opinions, the MOH disapproved the idea of taking “provinces, prefectural-level cities, and counties” as units to cope with community-level outbreaks; instead the MOH was in favor of making community-level response plans where the size of a community was to be locally determined so as to avoid excessive measures and allow for timely policy adjustment. Measures in the plan also included categorical case management, strengthening treatment of severely ill cases, lowering case fatality rates, mitigating damage caused by the epidemic, making prevention and control policies more relevant, focusing attention and medical resources on patient treatment and the monitoring of virus mutations, and adjusting prevention and control policies in a way that is more science-based, efficient and cost-effective.

On the basis of expert recommendations, on July 10th, 2009, the MOH changed its response policy from “treating Influenza A (H1N1) as a Category B infectious disease for which prevention and control measures for Category A infectious diseases were adopted” to “employing countermeasures per Category B infectious diseases,” thus coping with Influenza A (H1N1) as “an infectious disease subject to monitoring” instead of “an infectious disease subject to quarantine.” In the document announcing the change, the MOH also affirmed that it would continue adjusting its management policies along with discoveries and changes in the epidemic. The key issue in adjusting prevention and control measures for this epidemic was the determining of the virus severity. During this process, related decision-making entities not only focused on foreign epidemic information, practices of foreign governments, and related expert opinions, but also they took into consideration their own domestic realities.

Taking into consideration the special characteristics of the epidemic and treatment options in China, combined with the experience the WHO and other countries had in employing the newest countermeasures against the virus, a group of experts from the MOH developed the Management Plan for Home-based Isolation and Treatment of Mildly Ill Patients of Influenza A (H1N1) (Tentative), which was then issued on July 13th. According to this plan, confirmed cases of normal influenza symptoms, among non-high-risk groups, who hadn’t developed any other complications could be isolated and treated at home, and prevention and control measures were then targeted mainly at people who were at high risk of severe illness, including elderly people, children, and people with chronic disorders, so as to lower costs and increase efficiency. On July 16th, the WHO adjusted its global information disclosure on the pandemic and decided to no longer publish information on new confirmed cases. The MOH switched reporting on the epidemic to once every two days instead of once daily, signaling that China had shifted the focus of its prevention and control efforts to normal monitoring and management.

Bolstered Prevention and Control Efforts in Key Areas Including Schools, Communities, Towns, Hospitals, and Public Places

On June 19th, the Central Primary School in Shipai Town, Dongguan City, Guangdong, reported a concentrated outbreak among its students, which was the country’s first outbreak of the kind, with 56 confirmed cases. This outbreak had no imported case as the definite source of infection, which sparked a turning point in the national prevention and control efforts—i.e. communities and schools now became the focal points of the countermeasures. To this end, the MOE and the MOH jointly issued the Work Plan for Influenza A (H1N1) Prevention and Control in Schools (Tentative), with the goal of protecting schools from the virus. The summer holidays began in early July for primary and secondary schools as well as colleges and universities countrywide. Since various summer camp activities could have become a breeding ground for the epidemic, so the MOE once again issued a notice stressing the need for cancelling concentrated activities, and required careful reviews for planned student activities according to the principle of “no activity, if not necessary” and local epidemic situations. The MOH also stressed that the priority for the next phase of prevention and control would be to stop the aggregation of cases, especially preventing outbreaks in schools and communities.

Strengthened Scientific and Technological Research on Basic Research, Clinics, and Other Prevention and Control Mechanisms; Increased Scientific and Technological Reserves

In late May, the MOH and the MOST co-launched the “Emergency Research Project for Joint Prevention and Control of Influenza A (H1N1)” which included seven items. Apart from the development of fast diagnostic testing kits, this project covered the following seven areas: evaluation and development of biological protective equipment and disinfectant products; the evaluation and development of medications; an investigation into the genetic background of the Influenza A (H1N1) virus; an evaluation of protection effects from Chinese natural immunity and the seasonal influenza vaccination; the development of key technologies used to increase production capacity of influenza vaccine manufacturers; and the evaluation of clinical treatment methods and the research on case resource integration. The overall goal of this plan was to prepare the country for technological responses to a large scale epidemic.

The Peak of the Epidemic (September 2009–Mid-January 2010)

In this phase, the main strategy focused on containment and strengthening treatment of severely ill patients.

Strategic Backgrounds

Reported confirmed cases and severely ill cases rose rapidly beginning in September 2009, with severely ill cases peaking (at 1297) on December 6th. Influenza A (H1N1) cases in schools also increased considerably after the new semester began in September 2009. On October 4th, the first fatal case in China was reported in the Tibet Autonomous Region. With a significant increase in reported clustered cases, the continual rise of severely and critically ill cases in October, and the amounting fatalities, the Influenza A (H1N1) virus became the dominant strain of influenza in the country. Cases increased significantly into November, and infection remained at high levels for three consecutive weeks before reaching the peak of more than 1200 cases reported weekly. The proportion of Influenza A (H1N1) cases to seasonal influenza cases monitored by sentinel hospitals across the country peaked at the end of November. Of severely ill cases, children under nine years of age were the most affected, followed by high-risk groups such as people with chronic disorders, pregnant women, and those suffering from obesity, with complications including pneumonia, respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, etc. A national serological survey showed that an overwhelming majoring of Chinese people were susceptible to the virus, which meant a big high-risk population base. In light of school activities and National Day celebrations, the strategy adopted in this phase was focused on “strengthening prevention measures, controlling the spread of the virus in communities, bolstering treatment of severely ill patients, and mitigating damage caused by the epidemic” so as to contain the virus and avoid adverse social impact.

Main Countermeasures

Strengthened Treatment of Severely Ill Cases

In response to the spread of the pandemic, the central government allocated five billion RMB in funds for support of Influenza A (H1N1) prevention and control efforts, and required local governments to appropriate funds for tailored prevention and control purposes. These funds were used to deploy materials such as disinfectants, purchase protective and medical equipment and sterilizing equipment, and develop and produce vaccines. The funds also included 1.085 billion RMB for national pharmaceutical stockpiles, and the increase in antiviral drugs, clinical and treatment equipment.

On October 12th, 2009, the MOH issued the Guidelines on Diagnosis and Treatment of Influenza A (H1N1) (3rd Version, 2009), which included a revision in diagnostic criteria and added criteria for identifying severely and critically ill cases, with particular emphasis placed on the early identification and treatment of the two types of cases. On April 30th, 2010, the MOH issued the further revised Guidelines on Diagnosis and Treatment of Influenza A (H1N1) (2010), in which the clinical characteristics and treatment principles of children and pregnant woman were added. By that time a total of five versions of the diagnosis and treatment guidelines had been published.

Hospital led response efforts focused on (a) recruiting rescue staff and strengthening professional training, and (b) the use of antiviral drugs for treatment purposes. It is worth nothing that some clinical studies on Influenza A (H1N1) treatment garnered worldwide recognition; for instance, A Clinical Study on Symptoms and Therapeutics of Mildly Ill Patients of Influenza A (H1N1) was published in the world’s authoritative New England Journal of Medicine.

However, at the same time, certain issues came to light during the response efforts. Firstly, grass-roots capabilities for medical treatment were still inadequate. For example, many emergency medical centers lacked specialized healthcare personnel, ambulances, and related equipment and facilities; many pre-hospital emergency aid facilities in the central and western provinces, and even at the local level in the eastern provinces, were not fully established. In some areas, especially less developed ones with limited medical resources, local governments lacked the capital to invest in strengthening medical treatment capabilities and thus were faced with shortages in related equipment and facilities, antiviral drugs, and protective equipment. Secondly, medical treatment expenses for Influenza A (H1N1) patients were still being taken care of by the hospitals. In the early days of the national response efforts, the state stipulated that all Influenza A (H1N1) patients be treated free of charge, so designated hospitals paid medical and living expenses for the epidemic patients under their care. After the national prevention and control strategy was adjusted, four ministries including the MOH and the MOF jointly issued a document regarding treatment expenses which required the local governments to cover the costs for current or previous cases, and future cases would be settled through the urban employee insurance, the urban resident insurance, and the new rural cooperative medical care system. Nevertheless, obstacles arose during the implementation of this policy and some provinces to this day have yet to settle expenditures. Thirdly, designated hospitals, while bearing the loss in treatment expenses, also faced economic losses from the decrease in outpatients due to receiving and treating Influenza A (H1N1) patients, which produced an adverse effect on the hospital’s survival and development. This phenomenon predominantly occurred in less developed regions of the central and western part of the country. Fourthly, treatment of severely ill cases was costly, involving the use of protective equipment that was not covered by medical insurance, so many patients were unable or unwilling to pay for their treatment. As some Influenza A (H1N1) patients were part of the floating population, issues arose regarding medical insurance settlements between different regions. There was no definitive policy in terms of compensation for the proper financial channel, responsible entity, procedure, and/or time limits for expenses paid by designated hospitals whom took the brunt of mitigating the pandemic through patient treatment, transportation, and rehabilitation.

Conducted Nationwide Serological Surveys

In order to understand the prevalence of the virus in the population and to timely and scientifically judge epidemic trends, in December 2009, the MOH launched serological surveys on Influenza A (H1N1) infections and on the virus itself. The MOH required twelve provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government—including Beijing, Shandong, and Henan—to conduct three cross-sectional surveys according to the Plan for Sample Surveys in Several Provinces of Infection with the Influenza A (H1N1) Virus, in January, March–April, and August–September 2010, respectively. 4500 people were sampled in each province through multistage stratified random sampling methods, amounting to a total of 54,000 participants. All 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government, as well as the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, conducted four serological surveys according to the Plan for Quick Serological Surveys Countrywide of Infection with the Influenza A (H1N1), before January 10th, January 20–28th, February 20–28th, and March 20–28th, respectively. Survey findings proved to be crucial in providing judgments on the epidemic, and it was the only large-scale serological testing of its kind domestically in the world.

Stockpiled Vaccines and Antiviral Drugs and Launched a National Vaccination Program

In late September 2009, Beijing provided the first vaccinations to people participating in the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. In early October, Shandong also allocated its first vaccinations to workers preparing for the National Games of China. On November 6th, the MOE and the MOH jointly issued the Work Plan for Influenza A (H1N1) Prevention and Control in Schools, which made adjustments to the classification of Influenza A epidemics, school suspension principles, and response procedures. It also required schools to actively cooperate with health departments on student vaccinations. This was followed by an orderly process towards realizing the national vaccination program.

Strengthened Epidemic Monitoring and Health Education in Schools

During the national response efforts, the MOE as part of the Influenza A (H1N1) Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism worked in close coordination with the MOH as they adjusted the Work Plan for Influenza A (H1N1) Prevention and Control in Schools. At a grass-roots level, health departments and schools developed and implemented corresponding contingency plans and work plans, set up steering bodies, took prevention and control measures—including training, information dissemination, and cooperated with health departments on taking required response measures in schools.

To ensure the success of the response measures, health departments put programs in place according to the guideline of “respond effectively and scientifically.” The first was strictly monitoring the health conditions of students, faculty, and staff, including implementing morning inspections, absence registration and tracking systems in primary and secondary schools, and strengthening instructor-aided student attendance inspection in colleges and universities, all to ensure the timely detection, reporting, and treatment of students. The second was strengthening information and education efforts, with emphasis placed on campus-based dissemination of information about Influenza A (H1N1) prevention and control—through a combination of health education classes, bulletins, radio programs, and campus networks. The third was ensuring solid sanitary conditions in areas where students studied and lived, including carrying out health campaigns aimed to keep campuses clean. The fourth was reducing as many large gatherings as possible and exercising good epidemic prevention and control during National Day celebrations and military training sessions for students. The fifth was strictly implementing an epidemic reporting system, and in so doing, schools created the post of an epidemic reporter, established contact with local disease prevention and control departments, and adopted emergency measures. The sixth was cooperating with health departments on vaccinating students, faculty and staff as well as National Day celebration participants free of charge as arranged by local governments and the Influenza A (H1N1) Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism on the principle of “informed consent and voluntariness.” The seventh was carrying out school-based epidemic response measures, including isolating confirmed or suspected cases and close contacts under the guidance of health departments, and where circumstances were serious, taking such measures as shutting down schools according to opinions from health departments as well in accordance with the Work Plan for Influenza A Prevention and Control in Schools (Tentative).

Promoted Traditional Chinese Medicine

While increasing the stockpiling of antiviral drugs, the state also promoted the combination of Western and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The usefulness of TCM was stressed and practical clinical treatment solutions were developed in an effort to minimize case fatality rates and mitigate damage caused by the epidemic. For example, drawing upon the long history TCM’s effectiveness, Beijing introduced a formula against Influenza A, called “Jinhua Qinggan,” which was then patented and officially launched for clinical treatment. The clinical trials took place at Beijing Ditan Hospital and Beijing You’an Hospital. Of the 845 confirmed cases of Influenza A (H1N1), 326 were treated only with TCM. The prescriptions and some Chinese patent medicines which clinical experts chose for treatment purposes agreed with the pathogenesis, symptomatic characteristics, and basic therapeutic methods of Influenza A (H1N1). The trials showed that TCM alone could relieve symptoms like fever, sore throat, and cough, with no side effects when using the regular dosage. All the patients who used TCM were cured and discharged. The preliminary outcomes of the clinical trials provided a scientific basis for stockpiling TCM and Chinese patent medicines in response to the epidemic for the upcoming autumn and winter.

The Decline of the Epidemic (Mid-January–August 9th, 2010)

Treatment of severely ill patients, etiological monitoring, as well as commissioned expert evaluations of prevention and control efforts all continued during this phase.

In January 2010, new cases reported in the country fell significantly in number, with results of the monitoring showing lower levels of Influenza A (H1N1) activity than activity of seasonal influenza viruses. This was largely because health departments strengthened treatment of severely ill cases based on strategies from the previous phase, and also stepped up etiological monitoring of viruses. Education departments continued their vaccination health campaigns, and port quarantine departments did the same while making adjustments to quarantine practices. Specific measures included the following. Firstly, the large population moving around the country during the Spring Festival period was monitored, experts were organized to judge the current epidemic situation, Influenza A (H1N1) prevention and control efforts before and during the Spring Festival of 2010 were deployed, and guidance to regions and related departments on collaboration and preparedness—including information reporting, event management, vaccination, clinical treatment, prevention and control in priority areas, and health information and education—was provided. Secondly, more effort was put towards vaccination and the monitoring of adverse reactions. By December 31st, 2009, 49.91 million people nationwide had been inoculated. Surveillance findings showed that suspected abnormal reactions to the vaccine occurred roughly 12.4 per 100,000, and severely abnormal reactions occurred roughly 0.1 per 100,000. There were two deaths among those inoculated in December which proved to be unrelated to the vaccination. The rate of occurrence for adverse reactions did not exceed what was found in the domestic clinical trials and was consistent with data reported by the WHO and other countries. Thirdly, medical treatment was further strengthened. The central government appropriated a total of 397.56 million RMB to 17 central and western provinces as well as the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, which was used to strengthen the medical institutions’ treatment capacities for severely ill cases, including ICU equipment such as intensive care beds, respirators, and monitors. Health departments at various levels continued to provide guidance on treatment for severely ill cases, especially regarding the protection of pregnant women from the virus through TCM practices, and at the same time tightened control over nosocomial infections. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) sped up the storage and distribution of antiviral drugs such as Tamiflu, with more than 4.22 million doses of Tamiflu distributed among different regions and departments. Fourthly, case reporting, information disclosure, and public communication efforts were reinforced. This included the continued monitoring of cases with flu-like symptoms and of the Influenza A (H1N1) virus; strengthening the timely reporting of epidemic information; continued timely, open, and transparent dissemination of information and prevention and control efforts; as well as the continued exchange on epidemic knowledge and vaccinations among the public, especially high risk groups such as migrant workers, students, pregnant women, patients with chronic disorders, and tourists. The overall goal of these measures was to help guide the public in strengthening their own self-protection against the virus.

In lieu of global pandemic trends and characteristics as well as ample preparation, the National Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism and the Emergency Management Office of the State Council officially commissioned the School of Public Policy and Management (SPPM) of Tsinghua University in May 2010 to organize a multidisciplinary group of experts for a comprehensive, third-party evaluation of the national response to the Influenza A (H1N1) epidemic in China.

Post-pandemic Phase (Post-August 10th, 2010)

The focus of this phase centered on adjusting the influenza monitoring strategy and optimizing the monitoring network to better improve its quality.

On August 10th, 2010, the WHO announced the shift into the post-pandemic period, stating that Influenza A activity had returned to normal seasonal levels. The virus didn’t disappear completely in this phase as localized outbreaks were still considered likely. The WHO recommended, therefore, that countries continue to strengthen their influenza surveillance and play close attention to changes in influenza activity.

Evaluation and Analysis of China’s Major Response Strategies

Third party sources combined with our research data and analysis showed that the China’s response strategies were appropriate to the epidemic situation, policy implementation was successful, and policy adjustments also commendable—though some could have been executed in a timelier manner.

Firstly, the Chinese government zeroed in on the imported epidemic and responded proactively by implementing strict countermeasures at the onset of the outbreak. Main considerations included: (1) China’s national conditions: With a population of more than 1.3 billion people, over 700 million living in rural areas, China had quite a large floating population, which made prevention and control problematic; the floating population in 2009 was estimated at about 180 million people, and in 2008 there were 350 million people entering and leaving the country, all of which evinces the enormous complexity of coping with such a sudden outbreak. (2) Uncertainties about mutation of the emerging strain: As an emerging, unknown strain, the Influenza A (H1N1) virus was likely to mutate while in circulation and even evolve towards higher case fatality rates. (3) Compared with other countries, China’s emergency stockpiles and resources were heavily inadequate. By June 2009, the U.K. had stockpiled enough antiviral drugs for well over half of its population, German states each had a stockpile of antiviral drugs for 20% of their populations; but China’s national stockpile only contained 500,000 doses of Tamiflu, in addition to a local stockpile totaling 37,900 doses. (4) The WHO’s guidance as well as strict measures taken by affected countries: The Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic was the first public health emergency of international concern which the WHO had declared since the implementation of the IHR 2005. As an important member state of the WHO, China was obligated to abide by this international convention, through active epidemic response and reporting. Additionally, countries such as the U.S., Mexico, and Singapore adopted rather strict prevention and control measures both in the early days and at the peak of the pandemic, which provided groundwork for China’s own efforts.

Secondly, China’s Influenza A (H1N1) response strategies were adopted giving full consideration to the impact of the global financial crisis. China was also greatly impacted by the 2009 global financial crisis, and to deal with it effectively, its countermeasures not only had to be strict to protect normal economic and social operations from the possible spread of the virus, but at the same time the response efforts couldn’t be too severe otherwise they would adversely affect the economy. More importantly, as China’s economic development was crucial for global economic recovery, the state’s response strategies drew worldwide attention, and any action taken affected not only the people at home but also global economic and social development. Thus, China’s response policies had to take into consideration both the health and livelihood of its citizens, as well as domestic and international demands. In light of the above, from the perspective of safeguarding human lives, the Chinese government was determined to minimize damage, and so immediately adopted rather strict response strategies—which were adjusted as appropriate based on discoveries and changes in the epidemic—while striving to lower the impact of measures taken on normal economic and social operations. It turned out that such prevention and control measures were quite effective. As described in the foregoing analysis, the success in the country’s early containment strategy, and the school holidays that lasted from July to August, considerably delayed the advent of the epidemic’s peak, buying precious time for the nation to better prepare appropriate countermeasures.

It should also be noted that because there was a lack of understanding in the early phases of the epidemic in regards to the characteristics of the Influenza A (H1N1) virus, our strategic policy adjustments were not timely enough. The Influenza A (H1N1) virus had three prominent characteristics: First, transmission was quick; second, we slowly learned that the virus was mild in nature during the course of transmission; and third, its transmission, as was shown by expert studies, was mainly via respiratory droplets. Therefore, the adjustment of prevention and control measures could have been timelier had the epidemic situation been better judged and findings from local virological analysis and epidemiological surveys had been translated more swiftly into concrete prevention and control strategies and measures when the first wave of local cases occurred.

On the other hand, as situations differed from region to region owing to the vast territory of the country, further improvement was still needed in terms of coordination—under the guidance of national strategies—between different departments and between strategies of these departments and local governments. As stated above, on July 10th, 2009, the MOH changed its response policy from “treating Influenza A (H1N1) as a Category B infectious disease for which prevention and control measures for Category A infectious diseases were adopted” to “handling it with prevention and control measures for Category B infectious diseases,” coping with the virus as “an infectious disease subject to monitoring” instead of “an infectious disease subject to quarantine.” However, due to coordination problems between central departments and between central and local departments, some local level entry-exit inspection and quarantine departments still treated Influenza A (H1N1) as an infectious disease subject to quarantine.

Moreover, it must also be noted that chance also played a role in the success of the public health emergency response strategies. As part of its response effort, China shortened time to market for Influenza A (H1N1) vaccines, becoming the first country in the world to complete clinical trials for an Influenza A vaccine and the first country to launch a mass vaccination campaign. Although the vaccination campaign was a success, we cannot overlook the risks involved in this process.

The process from the discovery of a new influenza strain to vaccine production and marketing authorization takes at least 3–6 months, and if time for mass production is included, the process stretches out even further. As China still lagged behind developed countries, its vaccine production capacity, even though it was considerably increased for this epidemic, could only cover 10% of the population, while the previous seasonal influenza production capacity only covered 2%. Additionally, because an influenza virus is constantly mutating, it is highly possible that the vaccine strain being researched doesn’t match the pandemic strain, and that vaccine research and manufacturing simply can’t keep up with the speed of the virus’ mutation. Fortunately, the influenza pandemic virus didn’t mutate, which, adding to that the research results from the early phases, made it possible for the country to successfully develop a vaccine and use it for the masses. It should be noted, therefore, that in response to any future influenza pandemic, we should continue to actively carry out social intervention measures while simultaneously stressing medical interventions like vaccinations. Only then will our response strategy be both effective and reliable.

Contributor Information

Lan Xue, Email: xuelan@tsinghua.edu.cn.

Guang Zeng, Email: zeng4605@vip.sina.com.