Abstract

Recent studies have clearly shown that bats are the reservoir hosts of a wide diversity of novel viruses with representatives from most of the known animal virus families. In many respects bats make ideal reservoir hosts for viruses: they are the only mammals that fly, thus assisting in virus dispersal; they roost in large numbers, thus aiding transmission cycles; some bats hibernate over winter, thus providing a mechanism for viruses to persist between seasons; and genetic factors may play a role in the ability of bats to host viruses without resulting in clinical disease. Within the broad diversity of viruses found in bats are some important neurological pathogens, including rabies and other lyssaviruses, and Hendra and Nipah viruses, two recently described viruses that have been placed in a new genus, Henipaviruses in the family Paramyxoviridae. In addition, bats can also act as alternative hosts for the flaviviruses Japanese encephalitis and St Louis encephalitis viruses, two important mosquito-borne encephalitogenic viruses, and bats can assist in the dispersal and over-wintering of these viruses. Bats are also the reservoir hosts of progenitors of SARS and MERS coronaviruses, although other animals act as spillover hosts. This chapter presents the physiological and ecological factors affecting the ability of bats to act as reservoirs of neurotropic viruses, and describes the major transmission cycles leading to human infection.

Keywords: Bats, Megachiroptera, Microchiroptera, Rabies, Lyssaviruses, Hendra virus, Nipah virus, Henipaviruses, Japanese encephalitis virus, Flaviviruses, Coronaviruses

Introduction

It is now well recognized that more than 75 % of emerging diseases over the past 2–3 decades have been zoonoses. Many of these zoonotic viruses have arisen from wildlife sources and caused neurological disease, especially those emerging during this period in the Asian and Australasian regions (Mackenzie et al. 2001; Mackenzie 2005; Griffin 2010; Bale 2012; Wang and Crameri 2014). Most of the diseases emerging from wildlife have been from bats and rodents (Enria and Pinheiro 2000; Calisher et al. 2006; Goeijenbier et al. 2013; Luis et al. 2013). Bats are only second to rodents in terms of mammalian species richness (Wilson and Reeder 2005) and constitute about 20 % of all mammalian species. Thus, with their wide distribution and abundance, it is not surprising that there is growing awareness that bats are the reservoir hosts for a number of these emerging viruses (Calisher et al. 2006; van der Poel et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2007; Halpin et al. 2007; Wood et al. 2012; Smith and Wang 2013; Shi 2013) and suspected of being associated with many others on serological grounds. Not only have they been shown to be the reservoir hosts for rabies and related lyssaviruses but also for other human pathogens, or potential pathogens, such as SARS-coronavirus-like viruses (Lau et al. 2005; Li et al. 2005; Shi and Hu 2008), Ebola and Marburg viruses (Leroy et al. 2005; Gonzalez et al. 2007; Towner et al. 2007, 2009; Marí Saéz et al. 2014; Olival and Hayman 2014; Ogawa et al. 2015), Menangle virus (Philbey et al. 1998), and Hendra and Nipah viruses (Young et al. 1996; Halpin et al. 2000; Yob et al. 2001; Chua et al. 2002). This brief review looks at the biological features that make bats good reservoir hosts, and the more important neurological viruses associated with bats that are, or have the potential to be, transmitted to humans.

Bats as Reservoirs Hosts: Implications for Virus Transmission

The Evolution, Origin, Taxonomy, and Diversity of Order Chiroptera

The evolution of bats remains a controversial topic; bats have a poor fossil record and their phylogenetic relationships have been relatively understudied (Teeling et al. 2000, 2002). Historically, the mammalian Order Chiroptera has been divided into two suborders, the Megachiroptera, or Old World fruit bats, including flying-foxes, and the Microchiroptera, or echolocating bats (Simmons and Conway 2003). Taxonomic methods based on morphological cladistics of cochlea structure among Eocene fossil bats, complemented by some molecular data, led Simmons and colleagues to the conclusion that echolocation, originating secondary to flight, evolved only once and that the echolocating microchiropteran bats are monophyletic (Simmons and Conway 2003). Based on this study the 188 species of megachiropteran bats were grouped within a single family, Pteropodidae, and the other 917 species of bats were divided into 18 families.

However more recently molecular-based phylogenies suggest a far more complex paraphyletic relationship of echolocating bats suggesting echolocation evolved twice and that five families of echolocating bats (previously classified with the monophyletic microchiropteran bat families) are more closely related to the Pteropodidae (of note rhinolophid bats harbor viruses closely related to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV) (Springer 2013). These data suggest that the grouping of all echolocating bats into the suborder Microchiroptera is unwarranted and new suborders of bats have been adopted; the Pteropodiformes contains the Pteropodidae, Rhinolophidae, Hipposideridae, Rhinopomatidae, Craseonycteridae, and Megadermatidae, while the suborder Vespertilioniformes contains the other 12 families formerly of the Microchiroptera (Springer 2013). Within this review we will use the suborder terms Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera as these are the most familiar to many nonspecialists.

Irrespective of evolutionary controversy, bats are believed to have originated in the late Cretaceous/early Paleocene, some 65 million years ago, with three major microchiropteran lineages traced to Lauarasia and a fourth to Gondwana (Teeling et al. 2005). The Chiroptera underwent rapid speciation with at least 24 genera of bats extant by the Eocene [52–50 million years ago (Simmons and Conway 2003; Teeling et al. 2005)]. The divergence of the Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera, irrespective of suborder status, occurred well prior to the oldest fossil record from the Eocene. Although the evolution of flight may have preceded echolocation, fossil remains from the Eocene indicate echolocation was well established (Simmons and Geisler 1998; Simmons et al. 2010). Following the early evolution of flight and echolocation, bats have changed little as a taxonomic group relative to other mammals (Jepsen 1970). Bats also have traits (e.g., flight, sheltered roosts and ability to hibernate and entire torpor) which may have allowed them to preferentially survive the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K–T) extinction, occurring ~65 million years ago following the impact of the large bolide creating the 180–300-km-wide Chicxulub crater in northern Yucatan, Mexico (for more details see Wang et al. 2011a).

Bat Population Ecology

Bats are unique with regard to the abundance and density achieved by certain cave-dwelling species. Colonies of Mexican free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) can achieve numbers in excess of a million individuals, reaching densities of 500 individuals per square foot, and several species of Myotis achieve hibernating population densities of >300 per square foot (Constantine 1967a; Humphrey and Cope 1976; Tuttle 1976; Clawson 2002). The close proximity of numerous individuals packed into dense concentrations can obviously facilitate virus transmission by direct contact, such as biting or licking and other means, such as through respiratory transmission or contact transmission by transfer of infectious secreta and excreta. It is in caves harboring millions of closely packed free-tailed bats that airborne rabies virus transmission was documented (Constantine 1967b; Winkler 1968).

Tree roosting bats can also be highly gregarious with camps of pteropid bats containing thousands of individuals, often including more than one species, clustered within trees. In Australia, little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus) hang together with up to 30 individuals clustered on a single branch (Hall and Richards 2000). Species of microchiropteran bats roost in colonies of several dozen to thousands of individuals while less gregarious species may roost in small colonies or singly, such as Lasionycterus noctivagans, an important reservoir host of a variant of rabies virus often associated with bat-associated human deaths in the United States (Noah et al. 1998; Messenger et al. 2003b; Rupprecht and Gibbons 2004).

Diet and roosting behavior have been hypothesized as influencing exposure to viruses and susceptibility to infection. A provocative study, although extremely preliminary, found that the decreasing permanence and protection offered by roosting sites of bat species increased the “soluble part of the constitutive immune function ” (as measured by the in vitro bacterial killing activity of plasma against Escherichia coli), while increases in the cellular immune potential (measured as white blood cell count) varied with and body mass and diet (carnivorous bats having higher counts than insectivorous or frugivorous species) (Schneeberger et al. 2013).

Bat Flight and Movements

Bats are the only mammals able to fly, and many species travel considerable distances from roost sites to feeding locations. The entire or some proportion of the population of 87 species within ten families of bats migrate to some degree; migratory behavior has been less studied in the genus Pteropus but has been well established for eight species (for review see Krauel and McCracken 2013). Although most frugivorous bats will travel distances <200 km during a season when shifting roosts in response to the availability of fruit production (Rosevear 1965; Fleming and Eby 2003), a few species, such as the pteropodid bat, Eidolon helvum, will travel ~1500 km in one-way migrations from forest habitats to savannahs in Africa (Fleming and Eby 2003). Pteropus species have been recorded traveling across open sea between peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra and between Australia and New Guinea (Breed et al. 2006, 2010).

Migratory behavior among temperate bat species has been categorized as sedentary, regional, and long distance (Fleming and Eby 2003). Regional migration (typically <500 km) is common among European and North American species of Myotis while the long distance, one-way migrations of the subtropical/tropical Mexican free-tailed bats, Tadarida brasiliensis, exceed 1800 km (Krauel and McCracken 2013; Cockrum 1969; Griffin 1970). Unlike birds which may migrate long distances without feeding, bats forage as they migrate. Locally abundant, but widely distributed fruit resources, may serve to aggregate species of bats and other terrestrial fruit-eating mammals, such as great apes and ungulates, at feeding sites thus potentially enhancing the risk of intra- and interspecific transmission of viruses. Temporary seasonal clustering of bats and terrestrial mammals during dry seasons in Africa has been proposed as a means of promoting interspecific transmission of Ebola virus from a putative fruit bat reservoir host (Leroy et al. 2005) to other species (Pinzon et al. 2004).

A further example of how the migratory behavior of bats may influence the geographic distribution and genetic variability of viruses is illustrated by the lyssaviral variants associated with specific bat species and their overlap with human disease (Table 1). A variant of rabies virus maintained by the silver-backed bat, Lasionycterus noctivagans, and the eastern pipistrelle bat, , and known as the Ln/Ps variant (Franka et al. 2006), has been the most commonly recognized cause of indigenously acquired human rabies in North America over the last few decades (Noah et al. 1998; Messenger et al. 2003b; Rupprecht and Gibbons 2004). The summer and winter range of L. noctivagans in North America extends from central Canada to the southern United States (Rohde et al. 2004) overlapping the distribution of human rabies cases associated with the LN/PS variant. Phylogenetic studies of European bat lyssavirus subgroup 1a (EBLV-1a) suggest that virus trafficking between migratory bat species and the sedentary Eptesicus serotinus, a principal reservoir host, has contributed to the genetic homogeneity observed among EBLV-1a isolates (Davis et al. 2005b). Within a bat species, such as T. brasiliensis, both sedentary and migratory populations may exist and intermingle seasonally (Cockrum 1969; McCraken and Gassel 1998), providing a mechanism for viruses exchange and introduction.

Table 1.

Recognized or proposed members of the genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae

| Name | Species implicated in maintenance | Distribution | Annual human deaths | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICTV abbreviationa | ||||

| Rabies virus RABV | Dogs, wild carnivores, bats >50 spp. | Worldwide among dogs (with the exception of Australia and Antarctica, and designated rabies-free countries); Restricted to New World bats | ~55,000 (dog related) | Fooks et al. (2014), Knobel et al. (2005), Velasco-Villa et al. (2006), Mondul et al. (2003), Banyard et al. (2011), Schaefer et al (2005), and Bourhy et al. (1992) |

| European bat Lyssavirus EBLV-1 | Bats—Microchiroptera: Eptecicus serotinus, Tadarida teniotis, Myotis myotis, Myotis nattererii, Miniopterus schreibersii, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Pipistrellus pipistrellus, Plecotus auritus | Mainland Europe | Occasional | Serra-Cobo et al. (2002), Davis et al. (2005b), Picard-Meyer et al. (2011, 2014), Schatz et al. (2013), McElhinney et al. (2013), and Schatz et al. 2014 |

| European bat Lyssavirus EBLV-2 | Bats—Microchiroptera: Eptecicus serotinus, Myotis dasycneme; M. daubentonii | Europe, United Kingdom | Occasional | Fooks et al. (2003b), Brookes et al. (2005a), Harris et al. (2006, 2007), McElhinney et al. (2013), Schatz et al. (2013), and Miia et al. (2015) |

| Australian bat lyssavirus ABLV | Bats—Megachiroptera: Pteropus alecto, P. scapulatus, P. poliocephalus, P. conspicullatus | Australia; possibly SE Asia, including Philippines | Occasional | Allworth et al. (1996), Hooper et al. (1997), Gould et al. (1998, 2002), Hanna et al. (2000), Arguin et al. (2002), and Francis et al. (2014b) |

| Microchiroptera: Saccolaimus | ||||

| Flaviventris | ||||

| Bokeloh virus BBLV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Myotis natererii | Europe: France, Germany | None reported | Freuling et al. (2011, 2013), Picard-Meyer et al. (2013), and Nolden et al. (2014) |

| Aravan virus ARAV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Myotis blythi | Asia: Kyrghyzstan | None reported | Arai et al. (2003) |

| Irkut virus IRKV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Murina leucogaster | Asia: Eastern Siberia, China | None reported | Botvinkin et al. (2003) and Liu et al. (2013b) |

| Duvenhage virus DUVV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Miniopterus schreibersii, Nycteris thebaica | Africa: South Africa, Guinea | Occasional | Tignor et al. (1977), Paweska et al. (2006), and van Thiel et al. (2009) |

| Zimbabwe, Kenya, Swaziland | ||||

| Khujand virus KHUV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Myotis mystacinus | Asia: Tajikstan | None reported | Kuzmin et al. (2003) |

| Lagos bat virus LBV | Bats—Megachiropteran: Eidolan helvum, Micropterus pusillus, Nycteris gambiensis, Epomophourus wahlbergi, Rousettus aegyptiacus | Africa: Nigeria, Central Africa | None reported | Sureau et al. (1977), Meredith and Standing (1981), Crick et al. (1982), Markotter et al. (2006b), Kuzmin et al (2008a), Dzikwi et al. (2010), Hayman et al. (2008a), Nel and Rupprecht (2007), and Peel et al. (2013) |

| Republic, Egypt, Senegal, South Africa, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia. Kenya | ||||

| Mokola virus MOKV | Shrew—Insectivora: Crocidura spp., Rodentia: Lopyhromys silkapusi | Africa: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, South | Occasional | Shope et al. (1970), Wiktor et al. (1984), Nel and Rupprecht (2007), Sabeta et al. (2007), and Kgaladi et al. (2013b) |

| Shimoni bat virus SHIMV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Hipposideros commersoni | Africa: Kenya | None reported | Kuzmin et al. (2010) |

| West Caucasian Bat virus WCBV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Miniopterus schreiberbersi | Europe/Asia: Caucasus | None reported | Botvinkin et al. (2003) and Kuzmin et al. (2005, 2008b) |

| Africa: Kenya? | ||||

| Ikoma lyssavirus IKOV | Civet—Carnivora: Civettictis | Africa: Tanzania | None reported | Marston et al. (2012) and Horton et al. (2014) |

| Lleida virusb LLEBV | Bats—Microchiroptera: Miniopterus schreiberbersi | Europe: Spain | None reported | Aréchiga Ceballos et al. (2013) |

a ICTV International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

bAs yet unclassified new lyssavirus

Long distance movements of bats may also lead to regular, but not constant, contact between individual bats from different subpopulations allowing partial connectivity between colonies of bats (e.g., Pteropus spp. in Australia). A metapopulation may exist where a spatial mosaic involves a constellation of subpopulations of which, at any given time, some are susceptible, some infected, and some immune to a particular disease. This may permit viruses to persist in a species with a total population that would otherwise be too small to maintain the pathogen (Lloyd and May 1996).

Bat Echolocation

Microchiropteran bats are the only mammals to use “sophisticated echolocation” (Simmons and Conway 2003), although Rousettus aegyptiacus, a megachiropteran bat, uses a brief, low amplitude clicking that may aid in orientation (Holland et al. 2004). The intense energy required to produce echolocation emissions (Neuweiler 2000) may promote virus transmission by aerosols or droplets when bats are aggregated and in close proximity. This transmission route has been hypothesized to occur with rabies virus as virus can be recovered from the mucous or respiratory fluids of infected bats (Constantine et al. 1972). The evidence supporting possible rabies virus transmission by an airborne route under natural conditions in caves harboring large colonies of Mexican free-tailed bats was previously mentioned.

Bat Hibernation and Torpor

Most, if not all, temperate bat species are capable of entering into regulated torpor whereby their body temperature (T b) is allowed to fall below ambient temperature (T a) (Speakman and Thomas 2003), and many species enter true hibernation during winter (Lyman 1970). Additionally, some tropical microchiropteran and megachiropteran species reduce T b, but whether this is regulated torpor or caused by extreme peripheral vasoconstriction remains to be determined (Speakman and Thomas 2003).

The impact of torpor and hibernation on the immune response and the persistence of viral infections among experimentally infected bats has been investigated for Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and rabies virus (Sulkin and Allen 1974). The thermogenic organ, or brown fat, of bats has been suggested as a storage depot of various viruses and rabies virus has been isolated from this tissue from experimentally infected bats kept at low temperatures (Sulkin et al. 1959), in addition to naturally infected bats (Bell and Moore 1960). JEV studies with persistence are described below in the section “Flaviviruses.”

There are data suggesting that on rare occasions bats may experience abortive infection by rabies virus or unusually long incubation or latency periods (Messenger et al. 2003a). The presence of neutralizing antibody among apparently healthy bats and the delayed development of rabies among captured bats has been interpreted as suggesting recovery from or prolonged incubation following infection (Moore and Raymond 1970; Trimarchi and Debbie 1977). Decreased rabies virus pathogenicity has been inferred by subjecting experimentally infected bats (Myotis lucifugus, T. brasiliensis, and Anthrozous pallidus) to low temperatures (4–10 °C) and then observing the onset of rabies after transferring animals to temperatures of 22–29 °C (Sulkin and Allen 1974; Sulkin et al. 1959; Sadler and Enright 1959). In a mathematical model of rabies persistence in a colony of big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) during hibernation, a long incubation period played a significant role in maintaining dormant infection. Subsequent transmission during spring warming avoided epizootic “fadeout” (George et al. 2011).

Apparently healthy common vampires, Desmodus rotundus, surviving experimental rabies virus challenge can excrete virus in their saliva (Aguilar-Setién et al. 2005). Similarly, apparently healthy bats have been shown to harbor low levels of EBLV RNA suggesting that there is a nonreproductive infection stage or subacute persistence of viral RNA (Serra-Cobo et al. 2002; Wellenberg et al. 2002).

Bat Longevity

Bats mature slowly and live long lives in comparison to other mammals of similar bodyweight (Barclay and Harder 2003). Several species of microchiropteran bat, M. lucifugus, Plecotus auritus, and Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, have been shown to have life spans exceeding 30 years in the wild (reviewed in Barclay and Harder 2003). This extreme longevity in a small mammal places bats well outside the traditional regression line scaling life expectancy to mammalian size (Austad 2005). The impact of extreme longevity on the potential for bats to maintain and transmit viruses could be enormous when coupled with the possibility of bats developing a tolerant, persistent infection following infection by certain viruses.

Bat Genomics and Immunology

A recurring theme in studies of bat evolution and behavior is how immune function can covary with these elements. As noted above, roost behavior and diet may influence the constitutive elements of the immune system (Schneeberger et al. 2013). To better understand the roles played by both genetic and nongenetic factors in bats’ ability to coexist and coevolve with pathogens successfully for a very long history, it is essential to do comparative genomics studies between bats and terrestrial mammals. Since 2001, whole genome sequencing has been conducted for nine species of bats, including two Pteropus spp., three Myotis spp., Rhinolphus ferrumequinum, Megaderma lyra, Pteronotus parnelli, and Eidolon helvum.

Although comparative genomics and transcriptomics have revealed some genetic basis of specialized traits in bats including flight, echolocation, hibernation/torpor, longevity, and antiviral immunity, additional functional studies are required to confirm that the observed genetic difference does play a role in making bats exceptionally effective reservoir hosts for a large number of viruses which can be highly lethal in other mammals.

Bats are the only flying mammals and have a smaller genome of ~2 Gb (compared to ~3 Gb for human and mouse) consistent with increased metabolic demands of flight. Interestingly, despite having smaller sizes, bat genomes contain a similar number of annotated genes to those of land mammals. Phylogenomic studies to determine evolutionary relationship of bats with other mammals remain unresolved with conflicting studies concluding either bats diverged from horses or from a sister a group within the clade of ungulates, cetaceans and carnivores (Wynne and Tachedjian 2015).

If genetic factors play a major role in bats’ ability to host viruses without clinical diseases, we can expect the following possible genetic differences: (1) Bats have unique gene/pathway(s) not present in other mammals; (2) Bats lack common gene/pathway(s) present in other mammals; or (3) Bats have similar gene/pathway(s) as in other mammals, but their expression pattern(s) is different. Although there are cases of bat-specific genetic features, such as the deletion of the AIM2 inflammasome gene family (Zhang et al. 2013) or the presence of bat-specific microRNAs (Cowled et al. 2014), to a large degree the major genetic differences seem to be at the level of gene expression and regulation. Specifically, there seems to be a trend of high basal level expression of genes involved in innate defense mechanisms (L-F Wang, unpublished results).

Flight has played an important role in shaping different aspects of the evolutionary changes of bats. The evolution of flight has been linked to immunologically important concentrations of positively selected genes in the DNA damage checkpoint and nuclear factor kB pathways (Zhang et al. 2013). Additionally, the high metabolic cost of flying requires an increased body temperature and it has been hypothesized that flight may play a role in increasing the tolerance of bats to adverse effects of viral infections in a way analogous to fever in other mammals and that flight in bats has selected for the acquisition of a diversity of viruses that may cause disease when transmitted to other mammals (O’Shea et al. 2014).

The study of regulatory genes among bats that influence their potential as reservoir hosts has greatly expanded in the last decade, although data are still limited (Schountz 2013). Bats have been shown to harbor an adaptive immune system which may provide a tolerance (see reviews by Schountz 2013; Chan et al. 2013), inhibiting demonstrable disease, permitting asymptomatic virus shedding and promoting recombination and reassortment of different RNA viruses (Chan et al. 2013). Bats behaving “normally,” such as the common vampire, Desmodus rotundus, may survive experimental challenge with rabies virus and survive to excrete virus in their saliva (Aguilar-Setién et al. 2005). Similarly, “healthy bats” have been shown to harbor low levels of EBLV RNA suggesting that there is a nonreproductive infection stage or subacute persistence of viral RNA (Serra-Cobo et al. 2002; Wellenberg et al. 2002).

Cell lines obtained from bats are now being used to investigate viral infection, tissue tropism, and the immune responses to infection. Examples include cell lines obtained from multiple tissues of Pteropus alecto and tissues of Eidolon helvum and Rousettus aegyptiacus immortalized by introducing retroviral elements. Some, but not all, of the pteropid cell lines were susceptible to infection by Hendra and Nipah viruses (Crameri et al. 2009) and the Eidolon and Rousettus cell lines were susceptible to Rift Valley Fever and O’nyong-nyong viruses, and virus titer from supernatants was decreased with IFN induction (Biesold et al. 2011). A recent study comparing the response of bat and human cell lines to a highly pathogenic zoonotic virus showed early induction of innate immune processes in bats (Wynne et al. 2014). This finding suggests there may be divergent mechanisms at a molecular level that may influence host pathogenesis.

Rabies and Other Lyssaviruses

Members of the Genus Lyssavirus , and Their Association with Specific Chiropteran Hosts

The single-stranded, negative-sense RNA viruses of the family Rhabdoviridae, Order Mononegavirales, exhibit an extraordinary host range, infecting plants, invertebrates, fish, and mammals (Kuzmin et al. 2006). However, viruses within individual genera of this family can exhibit exquisite host specification as exemplified by the 14 viruses currently classified within or proposed as members of the genus Lyssavirus (Table 1). The antigenic and genetic profiles of lyssaviruses allow segregation into phylogroups (see Fig. 1). Antibodies raised experimentally in mice against inactivated virus from one phylogroup neutralize viruses within that phylogroup but not others. With the exception of Mokola virus and Ikoma lyssavirus, each of the representative genotypes of lyssaviruses has been isolated from bats which are also believed to serve as their reservoir hosts. There is a complex relationship between lyssaviruses and bats where the viruses may cause clinical disease in bats or may circulate in the bat population without any overt disease (Banyard et al. 2011). There is also increasing evidence that rabies-related viruses are found throughout much of Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia, but not in the Americas, whereas rabies virus is found in bats only in the Americas (Table 1). Transmission of lyssaviruses from bats to species of other mammalian orders, a process termed “spillover,” can cause fatal neurological disease among humans and other animals. The term rabies was once strictly reserved for the acute fatal encephalomyelitis caused by classical rabies virus. However, the clinical disease of rabies is now widely used to include the clinically and pathologically indistinguishable diseases caused by any Lyssavirus (Meredith et al. 1971; Lumio et al. 1986; Samaratunga et al. 1998; Nathwani et al. 2003; Fooks et al. 2003a; Banyard et al. 2011).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the lyssavirus phylogroups and their respective species. Nucleoprotein sequences (405 nucleotides) were aligned with ClustalW and the phylogenetic tree was visualized using TreeView version 3.2. Bootstrap values at relevant nodes are shown. According to the proposed antigenicity of each group of isolates, the viruses are divided into different phylogroups. Where available, accession numbers for sequences are rabies virus (RABV AY102999, AY062068, AY103008, AY062069, AY102993,AY352514, AY330735, AY062090, AY062070, AY062047), Lagos bat virus (LBV EF547459, EF547449, EF547447, GU170202), West Caucasian bat virus (WCBV EF614258), Shimoni bat virus (SHIBV GU170201), Mokola virus (MOKV AY062074,AY062077), Duvenhage virus (DUVV AY062079), European bat lyssavirus type 1 (EBLV-1 AY062088, EF157976), Irkut virus (IRKV EF614260), Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV AF418014), European bat lyssavirus type 2 (EBLV-2AY062091, AY062089), Bokeloh bat lyssavirus (BBLV JF311903), Khujand virus (KHUV EF614261), Aravan virus (ARAV EF614259), and Ikoma lyssavirus (IKOV JX193798). Several sequences within the phylogeny are unpublished and as such do not have accession numbers. The scale bar represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide site. The number of human cases are shown next to silhouettes where reported (Reprinted with permission from Fooks AR, Banyard AC, Horton DL, et al. (2014) Current status of rabies and prospects for elimination. Lancet 384:1389–1399)

The genus has been divided into three phylogroups: phylogroup I includes rabies virus (RABV), Duvenhage virus (DUVV), European bat lyssavirus (EBLV-1), European bat lyssavirus 2 (EBLV-2), Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), Aravan virus (ARAV), Khujand virus (KHUV), Bokeloh bat virus (BBLV), and Irkut virus (IRKV); phylogroup II includes Lagos bat virus (LBV), Shimoni bat virus (SHIBV), and Mokola virus (MOKV); and phylogroup III includes West Caucasian bat virus (WCBV) and possibly Ikoma lyssavirus (IKOV) (see Fig. 1) (Badrane et al. 2001; Fooks et al. 2014). An additional possible member of the genus has also been described from a bat in Spain, and named Lleida virus (Aréchiga Ceballos et al. 2013). The viruses in each of the phylogroups vary in their virulence (Markotter et al. 2009; Kgaladi et al. 2013a). Specific vaccines and immunoglobulins only exist for the pre- or postexposure treatment (PET) of phylogroup I rabies virus (Anon 1999a), however, these vaccines elicit high levels of neutralizing antibodies to other phylogroup I lyssaviruses (Brookes et al. 2005b). Immunization of laboratory animals with rabies vaccine with subsequent challenge with other lyssaviruses indicates that diminishing efficacy is a function of increasing phylogenetic distance from rabies virus (Hanlon et al. 2005).

Characteristic differences in sequence variation of lyssaviral isolates have permitted identification of the primary reservoir host species. Characterization and typing of distinct virus variants has provided insights into the evolution, host species range and geographic distribution of specific genetic lineages of viruses circulating among bats, and led to the identification of bat-associated variants, which through spillover, have caused rabies in humans and animals (Badrane and Tordo 2001; McQuiston et al. 2001; Davis et al. 2005b; Loza-Rubio et al. 2005; Franka et al. 2006; Nadin-Davis and Loza-Rubio 2006; Leslie et al. 2006).

Rabies Virus and Bats

The reservoir hosts for rabies virus are mammalian species in the Orders Chiroptera and Carnivora, although virtually all of the approximately 55,000 human deaths occurring globally each year are due to virus variants maintained by domestic dogs (Knobel et al. 2005). Clinical features of rabies are described in detail in Chapter 5. The first observation linking bats to rabies was made in 1911 when the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) was identified as the source of an epidemic of rabies among cattle in Brazil (Carini 1911). Human deaths attributed to bites received from vampire bats were first recorded from the island of Trinidad (Hurst and Pawan 1959; Pawan 1959). Outbreaks of human rabies due to vampire bats continue to be reported from Brazil (Batista-da-Costa et al. 1993; Sato et al. 2006), Costa Rica (Badilla et al. 2003), Peru (Lopez et al. 1992), Venezuela (Caraballo 1996), and Mexico (Martinez-Burnes et al. 1997; Velasco-Villa et al. 2006).

The recognition of insectivorous bats as reservoirs of rabies virus dates from 1953, when rabies was first described in a bat that attacked a 7-year-old boy in Florida (Scatterday 1954). Since that time, the number of rabid bats reported to CDC has increased, reaching 1680 in 2012, second in number only to raccoons (Dyer et al. 2013). The majority of indigenously acquired human rabies cases in North America over the past three decades have been caused by bat-associated variants (Messenger et al. 2003a, b). More than 30 species of North American bats have been identified as naturally infected by rabies virus (Constantine 1979; Mondul et al. 2003) and the number of bat species found to be infected in Mexico and in South America is rapidly growing (Nadin-Davis and Loza-Rubio 2006; Velasco-Villa et al. 2006; Escobar et al. 2015). Distinct virus variants of rabies virus may be associated with one or more bat species and research into species specificity and the evolution of bat-associated rabies virus is rapidly changing our knowledge-base on this subject (Hughes et al. 2005; Davis et al. 2006). Rabies virus has not been isolated from bats outside North, Central, and South America (Banyard et al. 2011).

Rabies virus variants circulating among bats are currently divided into four major groups and several additional subgroups (Nadin-Davis et al. 2001; Davis et al. 2006). Group I (four subgroups) contains virus variants primarily originating from highly colonial, migratory bats of the genera Myotis and Eptesicus, and are endemic to eastern Canada and the United States as far west as the State of Colorado (Davis et al. 2006). Group II (two subgroups) contains variants primarily originating from solitary or moderately colonial, migratory species of the genera Lasiurus and Pipistrellus and L. noctivagans, and are endemic to Canada and most of the United States; included here is a virus variant isolated from L. noctivagans and P. subflavus (Ln/Ps) which is the most common variant recovered from indigenously acquired human rabies in North America (Messenger et al. 2003b). Group III contains variants from Eptesicus fuscus, genetically distinct from group I, and is restricted to western Canada and the western United States (Nadin-Davis et al. 2001; Davis et al. 2006). Group IV (three subgroups) contains variants originating from colonial species of hematophagous bats and insectivorous bats from Central and South America. Various subgroups and paraphyletic clades within groups preclude making unequivocal statements concerning the endemic range and bat species infected by a particular group of viruses at this time (Davis et al. 2006). As additional samples become available and full genome sequencing is undertaken, finer resolution of phylogenetic relationships between virus variants and individual species can be achieved, as exemplified by recent studies of rabies virus from the genus Pipistrellus and L. noctivagans; the LN/PS variant may be two independently maintained rabies virus variants with distinct hosts (Franka et al. 2006).

African Lyssaviruses

In addition to rabies virus, five other lyssaviruses occur in Africa; DUVV, LBV, IKOV, SHIBV, and MOKV (Table 1) (Nel et al. 2000; Warrell 2010; Kuzmin et al. 2010; Banyard et al. 2011). Bats are believed to be the reservoir hosts for DUVV, LBV, and SHIBV (Markotter et al. 2006b; Kuzmin et al. 2010), but MOKV and IKOV have only been isolated from other wildlife species and no association has been found with bats.

LBV has been isolated from megachiropteran bats and domestic animals dying of rabies (Markotter et al. 2006b), with a single exception of one isolate from a water mongoose, Atilax paludinosus, Order Carnivora (Markotter et al. 2006a). The first isolate of LBV was obtained from a fruit bat in Nigeria in 1956 (Boulger and Porterfield 1958) and since that time additional isolates have been obtained from various species of fruit bats from Central African Republic, Egypt, Senegal, South Africa, Ghana, and Zimbabwe (Sureau et al. 1977; Meredith and Standing 1981; Crick et al. 1982; Markotter et al. 2006b); from single cats in South Africa and Zimbabwe (Crick et al. 1982; King and Crick 1988); and a dog in Ethiopia (Mebatsion et al. 1992). Indeed LBV may be the most common rabies-like virus in Africa and serological evidence has shown that it occurs throughout the range of the straw-colored fruit bat, Eidolon helvum, even in more isolated island colonies (Peel et al. 2013). DUVV has only been isolated a few times, with most isolates obtained from human infections and single isolates from two insectivorous bats, Miniopterus schreibersi and Nycteris thebaica (Paweska et al. 2006; Nel and Rupprecht 2007). SHIBV was isolated from a dead Commerson’s leaf-nosed bat (Hipposideros commersoni) in Kenya (Kuzmin et al. 2010).

MOKV has been isolated from shrews (genus Crocidura, Order Insectivora), rodents (Lopyhromys sikapusi, Order Rodentia), and humans (Shope et al. 1970; Kemp et al. 1972; Wiktor et al. 1984), and IKOV has been isolated from a single African civet (Civettictis civetta) (Marston et al. 2012). Although MOKV has never been recovered from a bat, but humans and domestic cats and dogs have been diagnosed with rabies caused by MOKV over an extensive geographic range including Ethiopia, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe (Familusi and Moore 1972; Foggin 1983; King and Crick 1988; Mebatsion et al. 1992; von Teichman et al. 1998; Nel et al. 2000; Bingham et al. 2001).

Little is known about the epidemiology of African lyssaviruses other than rabies. Domestic and feral dogs are the major reservoir for classical rabies virus in Africa with indigenous species of wild carnivores serving as reservoir hosts within several regions (Nel and Rupprecht 2007); in contrast to bats in the Americas, African bats have never been implicated in rabies virus maintenance or transmission.

DUVV and MOKV have been linked to sporadic cases of fatal encephalitis among humans (Meredith et al. 1971; Kemp et al. 1972; Familusi and Moore 1972; Familusi et al. 1972; Swanepoel et al. 1993; Paweska et al. 2006; van Thiel et al. 2009; Koraka et al. 2012). No human disease has been associated with IKOV, LBV, or SHIBV.

European Bat Lyssaviruses

EBLV-1 has been isolated from bats throughout Europe, mostly from the Serotine bat (Eptesicus serotinus) although the host range may be relatively broad, and accounts for most bat isolates in Europe. EBLV-2 is significantly less common and has been associated exclusively with Myotis bats (Myotis daubentonii and M. dasycneme). From molecular studies, EBLV- 1 and EBLV-2 have been further subdivided into two subgroups (Amengual et al. 1997; Fooks et al. 2003a; Davis et al. 2005b); EBLV-1a has been primarily isolated from the nonmigratory, colonial species E. serotinus in northern Europe; EBLV-1b has been isolated from E. serotinus obtained from northern Europe, France, and Spain; EBLV-2a has been primarily isolated from M. dasycneme from the Netherlands and M. daubentonii from the UK; EBLV-2b has been isolated from M. daubentonii from Switzerland (Serra-Cobo et al. 2002; Davis et al. 2005b).

Since 1977, four human deaths have been attributed to EBLV, two from EBLV-1 and two from EBLV-2 (Lumio et al. 1986; Roine et al. 1988; Khozinski et al. 1990; Bourhy et al. 1992; Fooks et al. 2003b; Nathwani et al. 2003). The recent case of fatal EBLV-2 infection in a Scottish bat conservationist was the first indigenously acquired case of rabies in the UK in 100 years (Nathwani et al. 2003). A photographer infected with EBLV-1 after a bite from a disoriented E. serotinus bat in Spain recovered due to previous immunization with rabies vaccine, as well as postexposure immunization (Van Gucht et al. 2013). EBLV-1 has been recovered from terrestrial mammals, five sheep in Denmark (Ronsholt 2002; Tjornehoj et al. 2006) and a stone marten (Martes foina) in Germany (Muller et al. 2004), and in captive zoo Egyptian fruit bats (R. aegyptiacus) in Denmark (Ronsholt et al. 1998), but spillover is either rare or goes undetected. It is possible that the virulence of ELBVs is lower than that of some other lyssaviruses; experimental inoculation of EBLV-1 into red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and sheep has resulted in death in only one of 14 sheep (Soria Baltazar et al. 1988; Vos et al. 2004; Tjornehoj et al. 2006). Furthermore, ELBV-1 was detected in a range of tissues from apparently healthy bats (Schreiber’s bent-winged bats, Miniopterus schreibersii, and greater horseshoe bats, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) in Spain (Serra-Cobo et al. 2002) and in healthy zoo fruit bats (R. aegyptiacus) (Wellenberg et al. 2002), showing that bats may survive infection with possible long-term maintenance of the virus in infected healthy animals. There have been no reported spillover cases of EBLV-2 into either wild or domestic animals.

Human cell-culture derived RABV vaccine prevented infection of mice from challenge with an EBLV-1 isolate from E. serotinus (Fekadu et al. 1988), as also demonstrated for EBLV-2 and ABLV (Brookes et al. 2005b). As in Australia, humans exposed to potentially rabid bats in Europe are treated with traditional rabies biologics (Nieuwenhuijs et al. 1992).

Two other lyssaviruses have been described in Europe; WCBV was isolated from a common bent-winged bat in south-west Russia (M. schreibersii) (Botvinkin et al. 2003; Kuzmin et al. 2005), and BBLV was isolated from a Natterer’s bat (Myotis nattererii) in Germany (Freuling et al. 2011) and subsequently from northeastern France in 2012 (Picard-Meyer et al. 2013) and a third isolation again from Germany (Freuling et al. 2013). Neither WCBV nor BBLV have been associated with human or animal disease. An addition tentative lyssavirus was recently isolated from a bent-winged bat (M. schreibersii) in Spain, but it has also not been associated with human or animal disease (Aréchiga Ceballos et al. 2013).

Australian Bat Lyssavirus

Australian bat lyssavirus ( ABLV ) was described in 1996 (Fraser et al. 1996). While Rhabdoviruses of the genus Ephemerovirus were known to occur, Australia had historically been considered free of lyssaviruses. However, St George (1989), postulating the origins of Adelaide River virus, an ephemerovirus antigenically related to rabies, had previously suggested the possibility of an undiscovered rabies-like virus in Australian bats, reflecting that the typically low prevalences of lyssaviruses in bats meant that an Australian bat lyssavirus might not become evident unless active surveillance of bats was undertaken, or unless man or a domestic animal became infected. Notwithstanding marked antigenic and genetic similarities to rabies virus, Australian bat lyssavirus is phylogenetically distinct, and represents a new lyssavirus genotype (Hooper et al. 1997; Gould et al. 1998).

ABLV has been detected in both suborders of bats in Australia (McCall et al. 2000; Gould et al. 2002; Warrilow et al. 2003). Phylogenetic analyses indicate that ABLV forms a monophyletic group which differentiates into two distinct clades, one associated with the pteropid species, and one with the insectivorous Saccolaimus flaviventris (yellow-bellied sheath-tailed bat), and that the two clades have a nucleotide divergence of up to 18.7 % (Guyatt et al. 2003). However, the ecology of ABLV is yet to be fully understood. Field (2005) found serological evidence of infection in numerous other bat species across five families, indicating that the bat–virus relationship is mature, and that additional variants may exist. Barrett (2004) reported a statistical association between species, age and health status and ABLV infection in bats, noting that most FAT-positive bats had a clinical history of generalized paresis, with a small number overtly aggressive, and others clinically indistinguishable from FAT-negative bats.

There have been three human deaths attributed to ABLV in Australia. The first case (in 1996) involved a wildlife rehabilitator who had been bitten by a yellow-bellied sheath-tailed bat in her care 5 weeks previously (Allworth et al. 1996; Speare et al. 1997; Hooper et al. 1997). The second case (in 1998) resulted from a bite from a pteropid bat following bat-initiated contact, and had an extended 2-year incubation following exposure in 1996 (Hanna et al. 2000). The third case (in 2013) also followed bat-initiated contact by a pteropid bat (Francis et al. 2014b). In all cases, the disease was similar to that caused by classical rabies (GT1) (Francis et al. 2014a). Both public health and animal health authorities in Australia strongly advise members of the general public not to handle bats and to seek medical advice should contact occur.

Standard preparations of cell-culture vaccine and human immunoglobulin against rabies virus are used to treat persons exposed or at risk of exposure to ABLV (Anon 2014). This regimen protects mice in experimental challenges (McCall et al. 2000; Brookes et al. 2005b), although the findings of Brookes et al. suggest that to ensure efficacy against ABLV, it may be prudent to maintain an antibody titer higher than that recommended for rabies virus. Bat rehabilitators and others likely to be exposed to bats are strongly encouraged to implement a preexposure vaccination strategy using cell-culture vaccine.

In 2013, two related equine cases of ABLV were reported. Virus nucleotide sequence from the horses was identical to the yellow-bellied sheath-tailed bat variant (Annand and Reid 2014). Prior to, and since this incident, there have been no reported cases of ABLV infection in terrestrial wildlife or domestic animals. In limited studies to date, experimental exposure of domestic cats and dogs to ABLV caused occasional and transient mild clinical signs, with no evidence of virus persistence. Most of the exposed animals seroconverted, and some had anti-ABLV antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid (McColl et al. 2007). Further studies are warranted to ascertain the susceptibility of terrestrial animals to bat lyssaviruses.

Rabies-Like Bat-Borne Viruses in Asia

Three lyssaviruses have been described in Asia—ARAV, which was isolated from a Lesser Mouse-eared Bat (Myotis blythi) in the Osh region of Kyrghyzstan, central Asia, in 1991 (Arai et al. 2003); KHUV, which was isolated from a female whiskered bat (M. mystacinus) in northern Tajikistan in 2001 (Kuzmin et al. 2003); and IRKV, which was isolated from the brain of a greater tube-nosed bat (Murina leucogaster) in 2002 in the town of Irkutsk in East Siberia (Botvinkin et al. 2003). IRKV was subsequently isolated from a greater tube-nosed bat in China (Liu et al. 2013b).

There have been a number of reports suggesting the presence of rabies-like viruses in bats in Asia, including serological studies in Thailand demonstrating the presence of neutralizing antibodies to ARAV, KHUV, IRKV, and ABLV largely associated with P. lylei fruit bats (Lumlertdacha et al. 2005); in China with evidence of rabies-like antibodies in various bat species but particularly in Rousettus leschenaultia fruit bats (Jiang et al. 2010); in Cambodia, with neutralizing antibodies to EBLV-1 in insectivorous bats and to ABLV in frugivorous bats (largely Cynopterus sphinx and P. lylei) (Reynes et al. 2004); and in Philippines, with neutralizing antibodies to ABLV in M. schreibersii (Arguin et al. 2002). While there have been no reports of disease due to bat-borne lyssaviruses in Asia, a number of anecdotal reports have described rabies-like illness following bat bites, particularly in China (Liu et al. 2013b).

Transmission of Lyssaviruses from and Between Bats

Transmission of bat-associated lyssaviruses occurs primarily by bite, when virus present in the saliva of an infected individual is directly inoculated into a susceptible individual. The potential for non-bite transmission of rabies virus among bats through saliva exchanged during mutual grooming has been suggested; transmission by such a mechanism may have precipitated an epidemic of rabies among kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), an African ungulate (Barnard et al. 1982). Mexican free-tailed bats may transmit rabies virus in utero, as virus isolates have been obtained from cell lines established with fetal tissue (Steece and Calisher 1989). Airborne transmission of rabies virus was suggested as the possible event leading to two cases of rabies in humans visiting a cave harboring millions Mexican free-tailed bats (Irons et al. 1957; Humphrey et al. 1960). In subsequent experiments, a number of caged animals placed within caves developed rabies, and rabies virus has been isolated from air sampled from these same caves (Constantine 1967b, c; Winkler 1968). Experimental aerosol infection of mice with RABV and EBLV-2 found that mice were highly susceptible to infection by inhalation whereas ELBV-2 required direct intranasal inoculation (Johnson et al. 2006). Most recently, laboratory mice and wild-caught big brown bats (E. fuscus) and Mexican free-tailed bats were exposed to aerosolized rabies virus. All the bats and some of the mice survived exposure and produced rabies neutralizing antibody, but this antibody provided poor protection for the bats to a subsequent challenge with rabies virus 6 months later (Davis et al. 2007). Corneal transplants have been the source of human-to-human transmission of rabies virus on several occasions (Houff et al. 1979; Anon 1980, 1981; Gode and Bhide 1988), and tissues transplanted from an individual infected by a bat-associated rabies virus variant caused multiple deaths among recipients in the United States (Srinivasan et al. 2005). Most human rabies cases caused by bat-associated variants of rabies virus have involved “cryptic” exposures, as patients or family members often cannot provide a positive history of bat bite (Noah et al. 1998; Gibbons 2002; Messenger et al. 2003b; Franka et al. 2006).

Although spillover of bat-associated lyssaviruses to terrestrial mammals is rarely found in systematic surveys (McQuiston et al. 2001), clusters of bat-associated rabies have been documented in gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) (Smith et al. 1986), red foxes (V. vulpes) (Daoust et al. 1996), and skunks (Mephitis mephitis) (Leslie et al. 2006) in North America. Such data suggest that rabies epidemics among terrestrial mammals may in rare instances be seeded by spillover from bats. Work on transmission and establishment of RABV between bat species shows diminishing frequencies of both cross-species transmission and host shifts with increasing phylogenetic distance (Streicker et al. 2010).

Understanding of the epidemiology and mechanisms of persistence of lyssavirus infection in bat populations is limited, but progress is being made through a combination of collection of field data and epidemiological modeling. Given the wide variation in life histories of different bat species, there may be significant variation in mechanisms of viral persistence in different situations. A study by George et al. (2011) of RABV in big brown bats (E. fuscus) in Colorado suggested that the slowing effects of hibernation on viral activity until susceptible individuals from the annual birth pulse become infected allows infection to maintain in the population. The persistence of EBLV-1 was investigated in a system involving multiple bat species which do not hibernate and it was found interspecies transmission was important for maintenance of infection in some species (Pons-Salort et al. 2014). Another study of LBV in a single species, Eidolon helvum, where hibernation is also absent, found a lack of increased mortality in seropositive animals suggesting infection did not result in disease after extended incubation (Hayman et al. 2012). This may suggest acute transmission of bat lyssaviruses in adapted bat hosts occurs at a much higher rate than the occurrence of disease.

Henipaviruses

The genus Henipavirus currently consists of three characterized viruses—Hendra virus, Nipah virus, and Cedar virus. Recently, evidence of related viruses has been reported in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America (Croser and Marsh 2013). Hendra and Nipah viruses emerged from fruit bats of the genus Pteropus (Order Chiroptera) to cause disease in livestock and humans (below). Both have been associated with severe neurologic disease, and both are classified as biosafety level 4 (BSL4) agents because they pose a high risk of laboratory transmission and life-threatening disease. As a consequence, laboratory work involving live virus should be done under physical containment level 4 (PC4) conditions. Hendra virus was first described in 1994 in Australia after a fatal disease outbreak in horses and humans in a horse-racing stable. Nipah virus was first described in 1999 in the investigation of a major outbreak of disease in pigs and humans in Malaysia.

Hendra Virus

In September 1994, an outbreak of acute respiratory disease of unknown etiology occurred in thoroughbred horses in a training complex in Brisbane (Queensland, Australia) (Murray et al. 1995). The syndrome was characterized by severe respiratory signs and high mortality, with 13 horses dying from acute disease. The trainer and a stable-hand suffered a concurrent severe febrile illness, with a fatal outcome for the trainer. Quarantine procedures and movement restrictions were applied, including a complete shutdown of the racing industry, and epidemiological investigations commenced (Baldock et al. 1996). The causal agent was shown to be a previously undescribed virus of the family , and initially named equine morbillivirus (EMV), but it was later renamed Hendra virus (after the Brisbane suburb where the outbreak occurred) when further characterization identified features inconsistent with morbilliviruses (Wang et al. 2000). To the end of 2014, a total of 51 incidents involving 92 confirmed or suspected equine cases have been reported in the adjoining eastern Australian states of Queensland and New South Wales (Biosecurity Queensland 2014) (Table 2; Fig. 2). The majority of incidents consist of single cases, even though in-contact horses are typically present. Case fatality rate in horses is around 75 % (Field et al. 2011); to date, all non-fatally infected horses have been euthanased because of uncertainty of the risk of recrudesence. Seven human cases have been reported, four of which were fatal; all seven cases are attributed to close and direct contact with infected horses. Two canine cases have been reported, both of which were on equine case properties (Anon 2013).

Table 2.

Identified Hendra virus spillovers in Australia since the virus was described in 1994 to 30 December 2014 (adapted from Biosecurity Queensland 2014)

| Year | Month | Location | State | Equine casesa (fatal) | Human cases (fatal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | August | Mackay | QLDb | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Sept | Hendra (Brisbane) | QLD | 20 (13) | 2 (1) | |

| 1999 | Jan | Trinity Beach (Cairns) | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 |

| 2004 | Oct | Gordonvale (Cairns) | QLD | 1 (1) | 1 (0) |

| Dec | Townsville | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| 2006 | June | Peachester | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Oct | Murwillumbah | NSWb | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| 2007 | June | Peachester | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 |

| July | Clifton Beach (Cairns) | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| 2008 | July | Redlands | QLD | 8 (7) | 2 (1) |

| Proserpine | 4 (3) | 0 | |||

| 2009 | Jul | Cawarral | QLD | 4 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Sept | Bowen | QLD | 2 | 0 | |

| 2010 | May | Tewantin | QLD | 1 | 0 |

| 2011 | June | Beaudesert, Boonah, Logan | QLD | 5 (5) | 0 |

| Wollongbar | NSW | 2 (2) | 0 | ||

| July | Park Ridge, Kuranda, Hervey Bay, Boondall, Chinchilla | QLD | 5 (5) | 0 | |

| Macksville, Lismore, Mullumbimby | NSW | 3 (3) | 0 | ||

| August | Currumbin | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Ballinac, Mullumbimby | NSW | 5 (5) | 0 | ||

| Sept | Beachmere | QLD | 3 (1) | 0 | |

| 2012 | Jan | Townsville | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 |

| May | Rockhampton, Ingham | QLD | 2 (2) | 0 | |

| June | Mackay | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| July | Rockhampton, Cairns | QLD | 4 (4) | 0 | |

| Sept | Port Douglas | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Oct | Ingham | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| 2013 | Jan | Mackay | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Feb | Kuranda | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| June | Macksville | NSW | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Laidley | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| July | Currumbin | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Macksville, Kempsey | NSW | 2 (2) | 0 | ||

| 2014 | March | Bundaberg | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 |

| June | Beenleigh | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| July | Gladstone | QLD | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Total | 50 incidents | 92 (82) | 7 (4) |

aIncludes confirmed cases and unconfirmed possible cases

b QLD Queensland, NSW New South Wales

cThree separate incidents

Fig. 2.

Map of the eastern Australian states of Queensland and New South Wales. The map shows the northern (Cairns), southern (Kempsey), and western (Chinchilla) extent of reported Hendra virus cases to December 2014. Additional marked locations provide an incomplete illustration of other case locations

There has been an escalating frequency of reported cases, with six incidents in the first decade, nine incidents between 2006 and 2010, then a super cluster of 18 incidents in 2011, and a further 19 between 2012 and 2014 (Biosecurity Queensland 2014). Whether this reflects an increased incidence of spillover, or increased awareness, diagnosis, and reporting is unknown. Similarly, since 2011, there has been an increased frequency of reported cases in New South Wales, and whether this reflects an expansion of a key reservoir host species is also unknown.

Nipah Virus

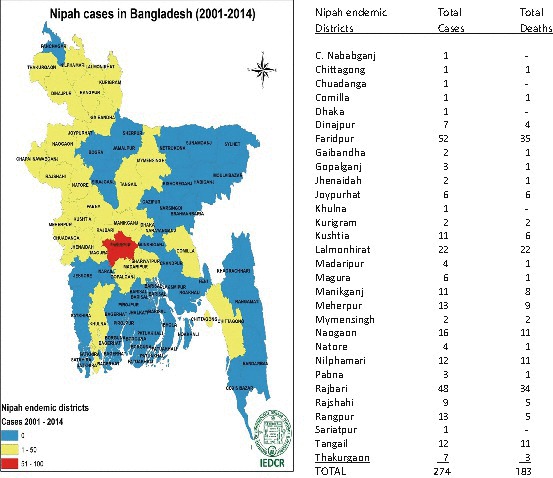

A major outbreak of disease in pigs and humans occurred in peninsular Malaysia between September 1998 and April 1999, resulting in the death of 106 of 265 reported human cases and the culling of over one million pigs (Chua et al. 1999, 2000; Nor et al. 2000). The outbreak spread to Singapore where a cluster of 11 cases with one death occurred at an abattoir (Paton et al. 1999). Initially attributed to Japanese encephalitis virus, the etiological agent was eventually shown to be another previously undescribed virus of the family Paramyxoviridae closely related to Hendra virus (Anon 1999b). The Malaysia outbreak primarily impacted pig and human populations, although horses, dogs, and cats were also infected. No cases of Nipah virus have been recorded in Malaysia since 1999. The disease reappeared, however, with multiple human cases diagnosed in Bangladesh in 2001 (Anon 2003). Near-annual seasonal clusters of human Nipah virus infections have been recorded in Bangladesh since (Anon 2004a, b, 2005; Hsu et al. 2004; Luby et al. 2006; Kulkarni et al. 2013; M Rahman, personal communication 2015) and occasionally in West Bengal (Chadha et al. 2006; Arankalle et al. 2011) (Table 3). In contrast to Malaysia where the majority of cases were restricted to areas where pig farming was common, the Bangladesh cases do not usually involve a domestic animal cycle (Epstein et al. 2006), and occur over a wide geographic area (Fig. 3). Food-borne transmission via date palm sap contaminated with bat saliva or bat urine is believed to be the major route of transmission (Epstein et al. 2006; Luby et al. 2006, 2009a; Rahman et al. 2012; Luby and Gurley 2012), although human-to-human transmission may also occur relatively frequently (Epstein et al. 2006; Gurley et al. 2007; Luby et al. 2009a, b; Luby and Gurley 2012).

Table 3.

Reported human cases of Nipah virus in Bangladesh and India1 since the first detection in 2001 to 30 December 2014

| Year | Month | Location | Cases | Deaths | CFR(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Jan–Feb | Siliguri1 | 66 | 45 | 68 |

| April–May | Meherpur | 13 | 9 | 69 | |

| 2003 | Jan | Naogaon | 12 | 8 | 67 |

| 2004 | Jan–April | Rajbari, Faridpur | 67 | 50 | 75 |

| 2005 | Jan–March | Tangail | 12 | 11 | 92 |

| 2007 | Jan–April | Thakurgaon, Kustia, Pabna, Natore, Naogaon | 18 | 9 | 50 |

| April | Nadia1 | 5 | 5 | 100 | |

| 2008 | Feb–April | Manikgonj, Rajbari, Faridpur | 11 | 9 | 82 |

| 2009 | Jan | Gaibandha, Rangpur, Nilphamari, Rajbari | 4 | 1 | 25 |

| 2010 | Feb–Mar | Faridpur, Rajbari,Gopalganj, Madaripur | 16 | 14 | 87.5 |

| 2011 | Jan–Feb | Lalmohirhat, Dinajpur, Comilla, Nilphamari, Rangpur | 44 | 40 | 91 |

| 2012 | Feb | Joypurhat, Rajshahi, Natore, Rajbari, Gopalganj | 12 | 10 | 83 |

| 2013 | Feb–April | Gaibandha, Jhinaidaha, Kurigram, Kushtia, Magura, Manikgonj, Natore, Mymenshingh, Naogaon, Nilphamari, Pabna, Rajbari, Rajshahi | 24 | 21 | 87.5 |

| 2014 | Jan–Feb | Manikganj, Magura, Faridpur, Rangpur, Shaariatpur, Kushtia, Rajshahi, Natore, Dinajpur, Dhaka, Chapai Nawabganj, Naogaon, Madaripur | 27 | 14 | 52 |

| TOTALs | 331 | 246 | 74 % |

The table compiled from WHO (2015), the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research for 2013–2014 (http://www.iedcr.org), and with additional information provided by Prof M Rahman, Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research, Dhaka (Personal Communication)

1Cases reported from outbreaks in India.

Fig. 3.

Map of Bangladesh showing districts with Nipah virus human cases, 2001–2014. Map provided by courtesy of Prof M Rahman, Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), Dhaka, Bangladesh

Phylogeny

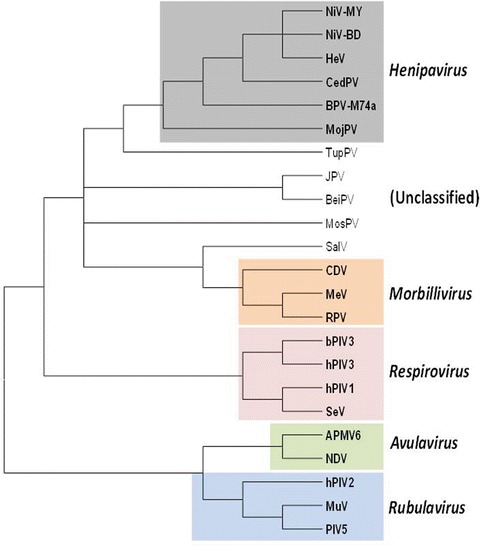

Initial nucleotide sequences of the matrix (M) and fusion (F) proteins genes established that Hendra virus had a greater homology with known morbilliviruses than with other genera of the family Paramyxoviridae (Gould 1996), but the sequence comparisons also revealed substantial divergence with other morbilliviruses. Subsequent sequencing of the entire genome confirmed Hendra virus as a member of the subfamily Paramyxovirinae, but identified differences that supported the creation of a new genus. Hendra virus had a larger genome size, the replacement of a highly conserved sequence in the L protein gene, different genome end sequences, and other sequence and molecular features (Wang et al. 2000). After the characterization of the Nipah virus genome, “Henipavirus” was proposed as the new genus, with Hendra virus the type species and Nipah virus the second member. The ICTV has formally recognized the genus Henipavirus, and the virus names, Hendra virus and Nipah virus. In recent years, at least three henipa-like viruses have been identified. These are the Cedar virus from an Australian flying fox (Marsh et al. 2012), the African bat paramyxovirus M74a from Ghana (Drexler et al. 2012), and the Mojiang virus from rats in China (Wu et al. 2014). Although their formal classification into the genus Henipavirus is yet to be confirmed, their close phylogenetic relationship with Hendra and Nipah viruses strongly support this putative classification (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree based on the N protein sequences of selected paramyxoviruses. Viruses used in this analysis are chosen based on their relative close genetic relationship with known henipaviruses in the subfamily Paramyxovirinae. Virus name (abbreviation) and GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Bat paramyxovirus/Eid hel/GH-M74a/GHA/2009 (BatPV-M47a) HQ660129; Beilong virus (BeiPV) DQ100461; Bovine parainfluenza virus 3 (bPIV3) AF178654; Canine distemper virus (CDV) AF014953; Cedar virus (CedPV) JQ001776; Hendra virus (HeV) AF017149; Human parainfluenza virus 3 (hPIV3) Z11575; J virus (JPV) AY900001; Measles virus (MeV) AB016162; Mojiang virus (MojPV) KF278639; Mossman virus (MosPV) AY286409; Nipah virus, Bangladesh strain (NiV-BD) AY988601; Nipah virus, Malaysian strain (NiV-MY) AJ627196; Rinderpest virus (RPV) Z30697; Salem virus (SalPV) JQ697837; Sendai virus (SeV) M19661; Tupaia paramyxovirus (TupPV) AF079780

The Role of Bats

Once the virus was identified, serological screening of ubiquitous native and introduced fauna in the vicinity of the index case was undertaken to determine the origin of the virus, but no evidence of Hendra virus infection. Following the identification of a second Hendra virus outbreak in horses near the city of Mackay (1000 km north of Brisbane), the focus of the wildlife surveillance shifted to species that were common to both locations and capable of moving between locations. Mammal species were given a higher priority than avian species. Of 27 flying foxes from two species tested in an initial survey, 40 % had anti-Hendra virus neutralizing antibodies (Field 2005), and in September 1996, 2 years after the first reported outbreak, virus was isolated from a grey-headed flying fox (P. poliocephalus) (Halpin et al. 2000). A concurrent survey of over 1000 flying foxes from the four mainland species (P. poliocephalus, P. Alecto, P. conspicillatus, and P. scapulatus) identified an estimated crude seroprevalence of 47 %. In a retrospective serological survey, antibodies neutralizing Hendra virus were identified in the sera of flying foxes collected in 1982 (Field 2005).

With the demonstration that Nipah and Hendra viruses were closely related, Malaysian bat species were targeted as possible reservoirs of Nipah virus, based on the established bat–Hendra virus link in Australia. Of 324 bats from 14 species surveyed in peninsular Malaysia, neutralizing antibodies to Nipah virus were found in 21 bats from five species, but predominantly in two Pteropus species, P. vampyrus and P. hypomelanus (Johara et al. 2001). Subsequently, Nipah virus was isolated from the urine of P. hypomelanus, and from dropped partially eaten fruit (Chua et al. 2002).

The identification of pteropid bats as the primary reservoir host of both Hendra and Nipah viruses (Young et al. 1996; Halpin et al. 2000; Johara et al. 2001; Chua et al. 2002) was a major breakthrough in understanding the ecology of these “new” viruses, and not only informed management strategies (Mackenzie et al. 2003; Field et al. 2004; Breed et al. 2011; Kung et al. 2013), but precipitated further investigation of the ecology of henipaviruses and factors associated with their emergence. Subsequent studies in Australia further elaborated the ecology of Hendra virus in pteropid bats (Plowright et al. 2008; Breed et al. 2011; Field et al. 2011). There is also evidence that some species may be more significant natural reservoirs than others (Smith et al. 2014; Goldspink et al. 2015; Edson D, Field HE, Broos et al. Routes of Hendra virus excretion in naturally infected flying-foxes: implications for viral transmission and equine spillover risk, submitted for publication), and that viral excretion in bats may be seasonal (Field HE, Jordan D, Melville D et al. Spatio-temporal aspects of Hendra virus infection in pteropid bats in eastern Australia, submitted for publication), which may explain the spatiotemporal occurrence of Hendra virus spillover events and inform risk management strategies. Subsequent studies in Malaysia (Rahman et al. 2010, 2013; Sohaytati et al. 2011) and Bangladesh (Epstein et al. 2008; Khan et al. 2010; Hahn et al. 2014a, b) have elaborated the ecology of NiV in bats. More recent studies have described the occurrence of henipaviruses on a global scale (Wacharapluesadee et al. 2005; Sendow et al. 2006; Hayman et al. 2008b; Drexler et al. 2009, 2012; Chong et al. 2009; Wacharapluesadee et al. 2010; Weiss et al. 2012: Breed et al. 2013; Croser and Marsh 2013; Peel et al. 2013; Muleya et al. 2014; Ching et al. 2015).

There is little doubt that pteropid bats are major reservoir hosts of Hendra and Nipah viruses (Field et al. 2007), and it is not surprising that additional related viruses have now been detected throughout their range, which extends from the west Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius, Madagascar, and Pemba Island, along the sub-Himalayan region of Pakistan and India, through southeast Asia, The Philippines, Indonesia, to the southwest Pacific islands and Australia. There are about 60 species in total. Flying-foxes range in body weight from 300 g to over 1 kg, and in wingspan from 600 mm to 1.7 m. They are the largest bats in the world, do not echolocate, and navigate at night by eyesight and their keen sense of smell. All species eat fruits, flowers or pollen, and roost communally in trees. Flying foxes are nomadic species, capable of traveling distances of hundreds of kilometers. Where the distributions of different species overlap, roosts are shared (Hall and Richards 2000; Corbet and Hill 1992; Mickleburgh et al. 1992; Nowak 1994). Thus the potential exists for interaction between flying fox populations across much of their global distribution. Recent reports of henipa-like virus detections in non-pteropid and in other mega bat species suggest that the bat–virus relationship may be even more ancient (Li et al. 2008; Croser and Marsh 2013).

Calisher et al. (2006) review the apparent association between bats and emerging infectious diseases. They contend that information about the natural history of most viruses in bats is limited, and specifically in relation to the family Pteropodidae, that only half of the 64 genera in this family (which includes flying foxes) have been adequately studied. Thus we know relatively little about the bats from which the henipaviruses have emerged. Calisher et al. (2006) pose a number of questions in relation to the role of bats and emerging zoonoses. Do bats possess special attributes that equip them to host highly pathogenic zoonoses? Are emergences such as Hendra and Nipah viruses infrequent and incidental events, or are we detecting only the tip of the iceberg? They conclude by calling for pre-emptive potential pathogen screening in wildlife, rather than the outbreak-response surveillance that typically occurs currently.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentations of human and animal cases infected with Hendra and Nipah viruses are described in more detail in section “Henipaviruses.”

Hendra Virus in Animals

The putative index case in Brisbane in 1994 was a heavily pregnant thoroughbred mare at pasture. She was moved to a training stable for nursing and died within 48 h. A further 12 horses in the stable and an adjoining training stable died in the following 14 days. Clinical signs included fever, facial swelling, severe respiratory distress, ataxia, and terminally, copious frothy (sometimes blood-tinged) nasal discharge. The incubation period based on clinical observations was 8–16 days. There were four non-fatal cases, two of which exhibited mild neurological signs. A further three horses were subsequently found to have seroconverted in the absence of obvious clinical signs (Baldock et al. 1996). A small number of horses in the stable remained unaffected. A second Hendra virus outbreak in horses was retrospectively diagnosed in October 1995 after the Hendra virus-attributed death of a farmer who suffered a relapsing encephalitic disease. This second incident (1000 km north of Brisbane) chronologically preceded the Brisbane outbreak by several weeks, and resulted in the death of two horses, a 10 year old heavily pregnant thoroughbred mare and a 2 year old colt in an adjoining paddock, after a 24 h clinical course (Rogers et al. 1996; Hooper et al. 1996). Numerous other horses on the property remained unaffected.

Extensive investigations were undertaken in relation to these two outbreaks. No antibodies to Hendra virus were found in over 5000 domestic animals surveyed (including 4000 horses) (Rogers et al. 1996; Ward et al. 1996) and no epidemiological link was identified between the two outbreaks. Retrospective investigations found no evidence of previous infection in horses in Queensland.

There are no pathognomonic signs for Hendra virus infection in horses. Common features are initial depression, inappetence, and fever, rapidly progressing to fulminating neurologic and/or respiratory disease (Biosecurity Queensland 2014). The primary pathogenesis is a loss of vascular integrity associated with vasculitis, the primary location of which may determine whether the predominant clinical presentation is respiratory (Murray et al. 1995; Baldock et al. 1996) or neurological (Field et al. 2010). The majority of equine incidents involve single cases. The typical absence of transmission to in-contact horses suggests that Hendra virus is not normally highly contagious in horses, and that direct contact or mechanical transmission of infectious material is necessary for transmission to occur.

Hendra Virus in Humans

There are seven recorded human cases of Hendra virus infection, all of which are attributed to direct and close contact with infected horses. A serological survey of bat rehabilitators found no evidence of bat-to-human transmission (Selvey et al. 1996). Human-to-human transmission has not been reported. There have been no human cases since 2009 despite an increasing frequency of reported equine cases, suggesting that risk communication to at-risk groups (horse owners, veterinarians, and para-veterinarians) and the adoption of risk minimization strategies have been effective. Clinical presentation is discussed in section “Henipaviruses,” but briefly infection is characterized by an acute respiratory syndrome and/or encephalitic syndrome or relapsing encephalitis (Selvey et al. 1995; Allworth et al. 1995; Playford et al. 2010; Mahalingam et al. 2012).

Nipah Virus in Animals

Pigs on commercial pig farms were the predominant infected species in the Malaysian outbreak. Herd-level infection was typically subclinical, with estimated morbidity and mortality rates of 30 % and 5 %, respectively (Nor et al. 2000). The incubation period was estimated to be 7–14 days. Observations of clinical cases suggested a varying presentation in different classes of animals. Affected weaners and porkers (2–6 months) typically showed acute febrile illness with respiratory signs ranging from rapid and labored breathing to harsh nonproductive cough. Attributed neurological signs included trembling, twitching, muscular spasms, rear leg weakness and variable lameness or spastic paresis. Adult sows and boars typically suffered a peracute or acute febrile illness with labored breathing (panting), increased salivation and serous, mucopurulent or blood-tinged nasal discharge. Neurological signs including agitation and head pressing, tetanus-like spasms and seizures, Nystagmus, champing of mouth, and apparent pharyngeal muscle paralysis were observed. The primary means of spread between farms and between regions was the movement of pigs. The primary mode of transmission on-farm was likely oro-nasal. Secondary modes of transmission between farms within local farming communities may have included roaming infected dogs and cats. Evidence of infection (virus isolation, immunohistochemistry, serology) and neurologic disease was found in dogs and horses in the outbreak area (Nor et al. 2000). Transmission studies in pigs in Australia at the CSIRO Australian Animal Health Laboratory established that pigs could be infected orally and by parenteral inoculation, and that infection could spread quickly to in-contact pigs. Neutralizing antibodies were detectable 10–14 days postinfection (Middleton et al. 2002). In a related study, experimental infection in cats caused neurological disease (Middleton et al. 2002).

The early epidemiology of the outbreak in the northern state of Perak, and the spillover mechanism that first introduced the infection to pigs remains uncertain, however, retrospective investigations indicated that Nipah virus was responsible for sporadic disease in pigs in Perak since late 1996 (Field et al. 2001). Mathematical modeling supports the hypothesis that at least one spillover event occurred before the 1998–1999 outbreak, and that a level of residual immunity in sows provided the right herd immunological conditions for infection to become endemic in the pig index case farm in 1998, thus providing a sustained reservoir of virus from which to infect other farms (Daszak et al. 2006; Pulliam et al. 2012).

Evidence of Nipah virus infection in domestic species has recently been reported in Bangladesh (Chowdhury et al. 2014).

Nipah Virus in Humans