Abstract

Introduction

Various methods have been used to interpret the reports of pediatric polypharmacy across the literature. This is the first scoping review that explores outcome measures in pediatric polypharmacy research.

Objectives

The aim of our study was to describe outcome measures assessed in pediatric polypharmacy research.

Methods

A search of electronic databases was conducted in July 2017, including Ovid Medline, PubMed, Elsevier Embase, Wiley Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EBSCO CINAHL, Ovid PsyclNFO, Web of Science Core Collection, ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis A&I. Data were extracted about study characteristics and outcome measures, and also synthesized by harms or benefits mentioned.

Results

The search strategy initially identified 8169 titles and screened 4398 using the inclusion criteria after de-duplicating. After the primary screening, a total of 363 studies were extracted for the data analysis. Polypharmacy (prevalence) was identified as an outcome in 31.4% of the studies, prognosis-related outcomes in 25.6%, and adverse drug reactions in 16.5%. A total of 265 articles (73.0%) mentioned harms, including adverse drug reactions (26.4%), side effects (24.2%), and drug-drug interactions (20.9%). A total of 83 studies (22.9%) mentioned any benefit, 48.2% of which identified combination for efficacy, 24.1% combination for treatment of complex diseases, and 19.3% combination for treatment augmentation. Thirty-eight studies reported adverse drug reaction as an outcome, where polypharmacy was a predictor, with various designs.

Conclusions

Most studies of pediatric polypharmacy evaluate prevalence, prognosis, or adverse drug reaction-related out-comes, and underscore harms related to polypharmacy. Clinicians should carefully weigh benefits and harms when introducing medications to treatment regimens.

Introduction

Medications play an essential role in effectively treating patients at any age [1]. The use of more than one medication is an inevitable consequence of pharmacotherapy for patients with multiple chronic conditions. The term ‘polypharmacy’ is often used to describe the use of multiple medications to treat one or multiple diseases. Polypharmacy is commonly used to describe the use of five or more prescribed medications for an adult, or two or more for a child [2–8]. Pediatric polypharmacy varies based on disease condition, medication class, duration of use, and healthcare setting [9]; however, a recent publication defined pediatric polypharmacy as the consumption of two or more distinct medications for at least 1 day [10]. Polypharmacy is associated with both benefits [11–13] and harms to patients; however, systematic or scoping reviews evaluating these outcomes are limited [9, 14–16]. Although polypharmacy is known to be prevalent among adult and elderly patients, there are also many reports of polypharmacy in pediatric populations [1, 6, 9]. For instance, the prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy in children has been reported to range from 2.9 to 27%. Often times, antipsychotic polypharmacy coincides with undesirable therapy outcomes including increased length of hospitalizations when polypharmacy is administered in inpatient settings [17, 18]. Feinstein and colleagues studied data from Colorado Medicaid beneficiaries and revealed that ≈ 35% of children were exposed to two or more concurrent medications for at least 1 day [9].

Polypharmacy in adults is sometimes necessary, but it may also be associated with an increased risk of adverse drug reactions or events, drug-drug interactions, hospitalizations, poor medication adherence, and mortality [19–21]. These increased risks may be extrapolated to the pediatric population. Most medications receive drug approval through the US Food and Drug Administration after solitary evaluation, and not in combination with other medications. Therefore, we are vastly unaware of possible drug-drug interactions, rare adverse events, or other health consequences that may occur with polypharmacy regimens. Many pediatric patients receive medications for chronic conditions for far beyond the length of time approved for drug trials, which limits our ability to predict possible health consequences from sustained use as the child receiving these medications matures and grows [22, 23]. The lack of safety and efficacy studies involving children is even more concerning, for it further limits our clinical decisions when managing complex disease states. A fine balance of preventing overtreatment while avoiding undertreatment is imperative to reduce harms and increase the benefits of polypharmacy in this patient population.

Compared with other children, those with chronic conditions are often exposed to more medications over longer periods of time, such as psychotropic agents, anticonvulsants, cardiovascular agents, and opioids [17, 18]. Yet, there are few literature evaluations describing outcomes associated with pediatric polypharmacy. This information is essential for advancing and guiding research in clinical decision-making processes, and for the formulation of clinical practice guidelines. Currently, we are unsure whether the prescribing patterns of physicians who employ the use of polypharmacy to manage complex conditions is problematic in the pediatric population.

Due to the varied nature of pediatric polypharmacy reports across the literature, there is a need to examine the differences through a comprehensive scoping review. Like a systematic review, a scoping review uses transparent and reproducible processes to define a research question, search for studies, and synthesize findings. However, compared with a systematic review, a scoping review tends to address a broader research question, may develop inclusion/exclusion criteria a posteriori or in an iterative fashion as the group reviews the existing literature, may not assess quality of studies, and the literature synthesis is more qualitative or descriptive than it is quantitative [24, 25].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review that explores outcome measures related to pediatric polypharmacy. The aims of our study were to describe outcome measures assessed in pediatric polypharmacy research and to conduct a detailed evaluation of adverse outcomes associated with polypharmacy.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a large scoping review of pediatric polypharmacy and limited our search to children aged 18 years old or younger to explore or map the literature. We used the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [26] and enhanced and adopted by Levac et al. [25]. Our transdisciplinary team utilized the methods established by previous scoping review methodology papers [25–27]. A search of electronic databases was conducted in October 2016, which included Ovid Medline, PubMed, Elsevier Embase, Wiley Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EBSCO CINAHL, Ovid PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection, ProQuest Dissertations, and Theses A&I. An updated search of electronic databases was conducted in July 2017. Search keywords included polypharmacy, multiple drug(s), hyperpolypharmacy, polytherapy, poly-medication(s), multiple medication(s), multiple prescription(s), and combination pharmacotherapy. To define the pediatric population, we used related vocabularies including child, infant, teen, pediatric, paediatric, school, pre-school, boy, girl, baby(ies), newborn, adolescent, juvenile, and minors (see Appendix 1 in the electronic supplementary material).

Eligibility criteria

Only original, primary studies on pediatric polypharmacy that defined or assessed polypharmacy as an aim, outcome, predictor, or covariate were included. We excluded non-English studies, studies pertaining solely to perinatal polypharmacy, case series, case reports, clinical trials, conference abstracts, letters, editorials, opinion pieces, review studies, and book chapters. We excluded experimental studies because we aimed to understand practice patterns and out-comes, which cannot be addressed by experimental studies due to their methodological uniqueness. Consistent with scoping review methodology, we did not assess the quality of the included studies.

Study selection

Screening studies for inclusion and exclusion began with a pilot screen of 100 abstracts, with the goal of reaching 80% interrater agreement at each level of screening. Screening was conducted in two stages. First, articles were independently screened based on title and abstract for inclusion or exclusion by two reviewers. Second, two independent reviewers screened all accessible full-text articles. Any disagreement between co-reviewers was resolved through a discussion or after reaching consensus from the full research team.

Data items and data collection process

Detailed information for the included studies was coded using a standardized data extraction tool that incorporated basic study information on characteristics listed in Table 1. Polypharmacy was identified as an outcome, aim, covariate, or predictor. Data about disease conditions, medication classes and categories, and definitions of polypharmacy (including number of medications and concurrence of medications) were also collected. Polypharmacy was also extracted as a primary or secondary aim, because it is often related to outcome measures. Any mention of harm and/or benefit in the included studies was also collected. Extracted harms varied and encompassed adverse drug reactions, side effects, drug interactions, adverse events, metabolic disorders, poor adherence, abnormal labs, toxicity, or death [28, 29]. Extracted benefits included drug combination for efficacy, treating complex diseases or augmentation (inherently referred to as beneficial polypharmacy), and rational polypharmacy. Other outcomes were compiled and labeled as ‘prognostics’, ‘pharmacokinetics’, ‘medication use evaluation (MUE)’, and ‘diagnostics’. Any clinical outcomes or those exploring behavioral change, measurement, exam, and action were reclassified under prognostics. Pharmacokinetic outcomes were those reports that studied dose and metabolism of medications or activity of blood markers. MUE included those non-polypharmacy outcomes reviewing the effect of the medication’s treatment duration, therapy adherence, and prescribing pattern. Diagnostic outcomes applied to any laboratory reports, imaging, and other measuring tools used in diagnosing disease (see Appendix 2 in the electronic supplementary material). Given the importance of adverse outcomes of polypharmacy, we further reviewed, mapped, and classified the characteristics of studies that reported adverse drug reaction(s) as their primary outcome measure and polypharmacy as a predictor.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 363 included studies

| Characteristic | No. of studies (%) | Characteristic | No. of studies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Data sources | ||

| USA | 126 (34.7) | Primary | 172 (47.4) |

| India | 23 (6.3) | Chart review | 90 (24.8) |

| Japan | 17 (4.7) | Claims | 44 (12.1) |

| Italy | 15 (4.1) | Electronic health records | 17 (4.7) |

| Brazil | 13 (3.6) | Healthcare setting | |

| Canada | 11 (3.0) | Outpatient | 197 (54.3) |

| Turkey | 11 (3.0) | Inpatient | 77 (21.2) |

| UK | 10 (2.8) | Combination | 27 (7.4) |

| Egypt: | 8 (2.2) | Others | 51 (14.0) |

| Germany | 8 (2.2) | Not reported | 11 (3.0) |

| Nigeria | 8 (2.2) | Study sample | |

| Poland | 8 (2.2) | 1–49 | 41 (11.3) |

| Sweden | 7 (1.9) | 50–99 | 64 (17.6) |

| China | 6 (1.7) | 100–499 | 145 (39.9) |

| South Korea | 6 (1.7) | 500–999 | 19 (5.2) |

| Multiple | 6 (1.7) | 1000+ | 85 (23.4) |

| Netherlands | 5 (1.4) | Not reported | 9 (2.5) |

| Spain | 5 (1.4) | Age | |

| Others | 70 (19.3) | Mean reported | 165 (45.5) |

| Year | Median reported | 32 (8.8) | |

| 1980–1985 | 5 (1.4) | Minimum reported | 310 (85.4) |

| 1986–1990 | 9 (2.5) | Maximum reported | 320 (88.2) |

| 1991–1995 | 20 (5.5) | Children-only study | |

| 1996–2000 | 29 (8.0) | No | 44 (12.1) |

| 1996–2005 | 58 (16.0) | Yes | 319 (87.9) |

| 2006–2010 | 74 (20.4) | Sex reported | |

| 2011–2015 | 117 (32.2) | No | 75 (20.7) |

| 2016–2017 | 51 (14.0) | Yes | 288 (79.3) |

| Design | Health insurance | ||

| Case-control | 4 (1.1) | Public | 46 (12.7) |

| Cross sectional | 235 (64.7) | Private | 8 (2.2) |

| Prospective cohort | 56 (15.4) | Combination | 19 (5.2) |

| Retrospective cohort | 68 (18.7) | Not Reported | 290 (79.9) |

| Polypharmacy identified as: | |||

| Primary aim | 238 (65.6) | ||

| Primary outcome | 114 (31.4) | ||

| Main predictor | 124 (34.2) | ||

| Covariate | 99 (27.3) |

Data Synthesis

EPPI-Reviewer 4 software was used for screening, data extraction, mapping, and synthesis [27]. Using this software, we were able to determine the frequency distribution of coded information and qualitative synthesis of text information at the study level [30].

Results

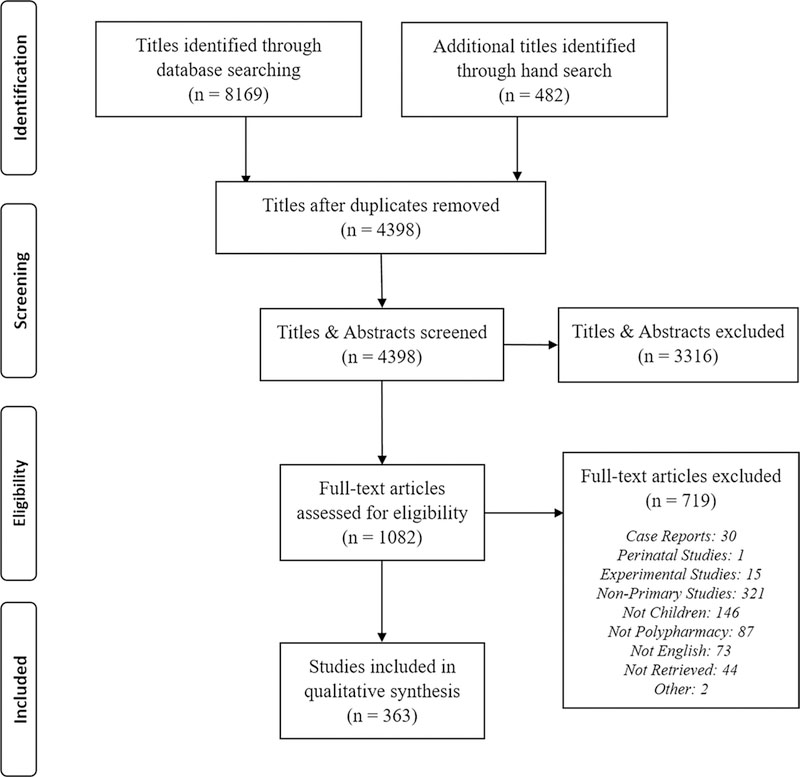

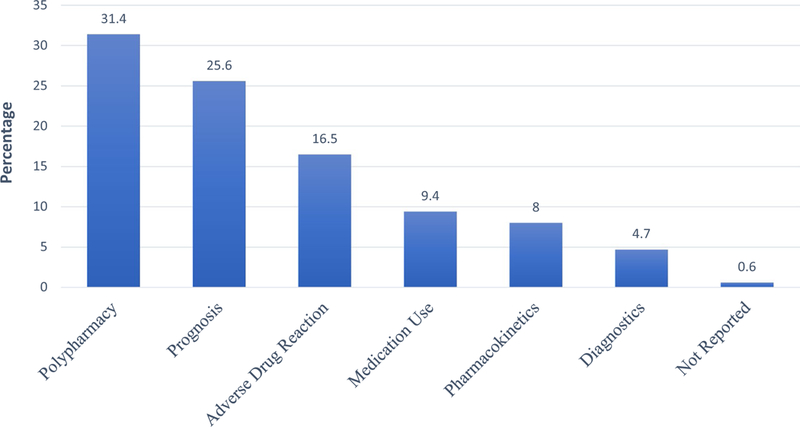

The search strategy identified 8169 titles (Fig. 1). After de-duplicating records, a total of 4398 abstracts and titles remained for the first screening step. During the first screening step, 1082 studies qualified for screening on full text, resulting in a total of 363 studies, which were extracted for the primary data analysis. Most studies originated in the USA (n = 126, 34.7%), India (n = 23, 6.3%), Japan (n = 17, 4.7%) or Italy (n = 15, 4.1%). Polypharmacy was identified as an aim, outcome, main predictor, or covariate in 238 (65.6%), 114 (31.4%), 124 (34.2%), and 99 (27.3%) of the studies, respectively (Table 1). Polypharmacy was identified as the most frequent outcome measure (n = 114, 31.4%), followed by prognosis (n = 93, 25.6%), adverse drug reaction (n = 60, 16.5%), medication use (n = 34, 9.4%), pharmacokinetics (n = 29, 8.0%), and diagnostics (n = 17, 4.7%) [Fig. 2].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies identified, screened, and extracted [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009]

Fig. 2.

Primary outcome measures identified in 363 studies

Some of the included studies reported more than one harm. A total of 265 articles (73.0%) mentioned harms. Adverse drug reaction was mentioned the most (n = 96, 26.4%), followed by side effect (n = 88, 24.2%), drug-drug interaction (n = 76, 20.9%), adverse event (n = 75, 20.7%), metabolic disorder (n = 30, 8.3 %), poor adherence (n = 55, 15.2%), abnormal lab result (n = 28, 7.2%), behavioral toxicity (n = 18, 5.0%), and death (n = 16, 4.4%) [Table 2]. Benefits of pediatric polypharmacy were less frequently reported in the included studies. Out of all pediatric polypharmacy articles, only 83 studies (22.9%) stated any benefit, 40 of which (48.2%) identified combination for efficacy, 20 (5.5%) combination for treatment of complex diseases, 16 (4.4%) combination for augmentation, and 14 (3.9%) combination for rational drug use.

Table 2.

Benefits and harms mentioned in any section of 363 included studies

| Harms and benefits | No. of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Harms | |

| Mentioned any harm | 265 (73.0) |

| Adverse drug reactions (injury happens by taking medication at the normal doses; could be predictable or unpredictable [74]) | 96 (26.4) |

| Side effects (an undesired effect that occurs when the medication is administered regardless of the dose [29]) | 88 (24.2) |

| Drug-drug interaction | 76 (20.9) |

| Adverse event (an undesired occurrence that results from taking medication correctly that includes adverse drug reaction, medication error, dose reduction and discontinuation of therapy [74]) | 75 (20.7) |

| Poor adherence (limited patient compliance with agreed recommendation from a health care provider [75]) | 55 (15.2) |

| Metabolic disorder | 30 (8.3) |

| Abnormal laboratory results | 28 (7.7) |

| Behavioral toxicity (common among medicinal drug users. Drugs frequently produce adverse effects and cause the users to not be adherent to the accurate therapy regimen [76]) | 18 (5.0) |

| Death | 16 (4.4) |

| Benefits | |

| Mentioned any benefit | 83 (22.9) |

| Combinations for efficacy (any disease treatment with two or more drugs aiming to reach efficacy with lower doses or lower toxicity drugs; gain additive or synergistic effects; or combat expected acquired resistance or minimize the possibility for development of drug resistance [77]) | 40 (11.0) |

| Treat complex diseases (when disease is chronic or refractory and the monotherapy is not effective. In this situation, add-on therapy is frequently practiced) | 20 (5.5) |

| Augmentation (the addition of a second agent to an existing medication regimen with the aim of achieving improved clinical response [78]) | 16 (4.4) |

| Rational drug use (when a patient receives appropriate medications based on their clinical needs, with individually adjusted dosage, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them, the health system and the community [79]) | 14 (3.9) |

Thirty-eight studies reported adverse drug reactions as an outcome, where polypharmacy was a predictor [31–68]. As summarized in Table 3, these studies were designed variably, including retrospective (n = 8) [33, 36, 37, 50, 54, 58, 62, 65], prospective (n = 8) [34, 35, 41, 45, 51, 56, 60, 67] and cross-sectional designs (n = 22) [31, 32, 38–40, 42–44, 46–49, 52, 53, 55, 57, 59, 61, 63, 64, 66, 68]. Most of the studies that reported adverse outcome variables (n = 28) were conducted in the USA, in an outpatient setting (n = 23), in neurological disorders (n = 36), and on central nervous system (CNS) medication(s) [n = 36]. Only four studies examined outcomes in cohorts of more than 1000 patients. As cited in Table 3, Bali et al. studied the cardiovascular safety of concomitant use of atypical antipsychotics and long-acting stimulants using a large cohort through claims data on children aged 6–16 years [36]. They showed polypharmacy was associated with increased risk of adverse drug reactions by 19%, but it was neither clinically nor statistically significant. McIntyre and Jerrell utilized South Carolina Medicaid claims data of children and examined the association between multiple antipsychotic treatment and cardiovascular and metabolic adverse events and showed an increased risk in multiple therapy compared with monotherapy [54]. Hilt et al. also reported a higher risk of adverse effects with multiple therapies, in a large cohort of children aged 3–17 years [48]. Patel et al., in their large retrospective cohort study, utilized an electronic medical record database and compared treated children and adolescents with bipolar disease with untreated pediatric patients. They concluded that antipsychotics and mood stabilizers are significantly associated with increased body mass index, especially when used in combination with other medication(s) [58].

Table 3.

Included studies that reported adverse drug reactions as an outcome variable

| Study (y of publication) | Country | No. of par- ticipants (age < 21 y) |

Aim | Study design | Care setting | Global pharmaco- logical category |

Diagnostic group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Qudah et al. (1991) [31] | Canada | 88 | To study further the role of carbamazepine-10–11-epoxide in producing neurotoxicity | Cross-sectional | NR | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Allarakhia et al. (1996) [32] | USA | 259 | [To] retrospectively review [clinical] experience with VPA and thrombocytopenia in 167 children evaluated at [an] institution over a 3-y period | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Amitai et al. (2015) [33] | Israel | 104 | To investigate the long-term effects of VPA treatment on thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, white blood cell and platelet count, liver function tests, and metabolic parameters in adolescents | Retrospective cohort |

Inpatient | CNS agents | Combination |

| Anderson et al. (2015) [34] | UK | 180 | To prospectively determine the nature and rate of ADRs in children on AEDs | Prospective cohort | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Anghelescu et al. (2008) [35] | USA | 117 | To examine the safety of concurrent use of epidural and intravenous opioids in a consecutive series of 117 epidural infusions in pediatric pts and compare findings to those reported by other investigators | Prospective cohort | Inpatient | Analgesic antiinflammatory | Somatic |

| Bali et al. (2019) [36] | USA | 37,903 | To examine cardiovascular safety of concomitant use of long acting stimulant and atypical antipsychotic in children and adolescents with ADHD | Retrospective cohort | Outpatient | Psychotropic agents | Psychiatric |

| Becker et al. (2005) [37] | USA | 228 | [To study] the effects of psychotropic medications on the weight of adolescent pts | Retrospective cohort | Inpatient | Psychotropic agents | Psychiatric |

| Burch (2011) [38] | USA | 59 | To discover whether children in a pediatric rehabilitation setting are at higher risk for AEs because of polypharmacy, or at a lower risk because of relative overall clinical stability | Cross-sectional | Inpatient | Combination | Not specific |

| Cramer et al. (2011) [39] | Multiple | 255 | To compare AEs in patients with epilepsy taking different AEDs using standardized physician-completed questionnaires | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| De Las Salas et al. (2016) [40] | Colombia | 772 | To describe the ADRs in inpatient children aged < 6 y in two general pediatrics wards located in Barranquilla, Colombia | Cross-sectional | Inpatient | Combination | Somatic |

| Dos Santos and Coelho (2006) [41] | Brazil | 272 | To investigate the occurrence of ADRs and associated risk factors in a pediatric hospital in northeast Brazil, from August to December 2001 | Prospective cohort | Inpatient | CNS + psychotropic agents + others | Combination |

| El-Khayat et al. (2003) [42] | Egypt | 130 | To investigate the effect of epilepsy and AEDs on both the physical and hormonal aspects of the sexual development of male pts with epilepsy | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| El-Rashidy et al. (2015) [43] | Egypt | 60 | To evaluate cardiac autonomic status in children with epilepsy on AEDs | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Farhat et al. (2002) [44] | Lebanon | 29 | [To study] the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency and bone mineral density in ambulatory pts on AEDs, [and to further explore] the impact of chronicity of intake of AEDs on bone density | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Galas-Zgorzalewicz et al. (1996H45] | Poland | 63 | To investigate the periodontal condition of children and adolescents using various AEDs such as carbamazepine, VPA or a combination of these drugs | Prospective cohort | NR | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Ghose and Taylor (1983) [46] | UK | 84 | To assess the serum copper and zinc levels in epileptics receiving long term medication | Cross-sectional | Schools | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Hallioglu et al. (2008) [47] | Turkey | 92 | To investigate the effects of epilepsy and various AEDs on heart rate variability | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Hilt et al. (2014) [48] | USA | 1347 | To investigate the side effect risks from using one or more psychiatric medications (including antipsychotics, antidepressants, α2-agonists, benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and stimulants) among a national cohort of children and adolescents | Cross-sectional | Parents | CNS + psychotropic agents | Psychiatric |

| Junger et al. (2015) [49] | USA | NR | To establish the MCIDs for the PESQ (Pediatric Epilepsy Side Effects Questionnaire) using a distribution-based method | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Kaplan et al. (2016) [50] | USA | 108 | To determine which anticonvulsants provided optimal seizure control and which resulted in the fewest side effects | Retrospective cohort | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Kim et al. (2010) [51] | South Korea | 151 | To verify the actual incidence and define the characteristics of topiramate-induced hypohidrosis | Prospective cohort | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Ko et al. (2001) [52] | Hong Kong |

144 | To investigate the relationship of thrombocytopenia, defined as a platelet count of <150 × 109 /L (normal range, 150–450 × 109 /L), with VPA therapy, age, duration of VPA therapy, and polytherapy | Cross-sectional | Outpatient, Inpatient |

CNS agents | Neurology |

| Kwon et al. (2004) [53] | South Korea |

152 | [Evaluate] for drug-induced QT prolongation to see if the use of AEDs contributes to or controls sudden unexpected death in epileptic pts | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| McIntyre and Jerrell (2008) [54] | USA | 4140 | To compare the incidence/prevalence of metabolic, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular events in an antipsychotic - treated cohort | Retrospective cohort |

Outpatient | Psychotropic agents |

Psychiatric |

| Mikati et al. (2007) [55] | USA | 143 | To identify risk factors for subclinical hypothyroidism (thyroid-stimulating hormone levels >5 mlU/mL) in pts receiving VPA therapy | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Ohtahara and Yamatogi (2004) [56] | Japan | 928 | To examine the safety of zonisamide, including AEs and teratogenicity in a post marketing prospective follow-up survey of Japanese pts treated for 1–3 ys with zonisamide, either as monotherapy or as a component of polytherapy | Prospective cohort |

Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Otsuka et al. (1994) [57] | Japan | 79 | To evaluate the significance of measuring urinary W-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase and guanidinoacetic acid in the chronic treatment of childhood epilepsies | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Patel et al. (2017) [58] | USA | 2299 | To assess the long-term effect of all treatment options for pediatric bipolar disorders on body mass index | Retrospective cohort | parents | Psychotropic agents | Psychiatric |

| Rashed et al. (2012) [59] | China | 329 | To determine the epidemiology of and identify risk factors for drug-related problems in hospitalized children in Hong Kong | Cross-sectional | Inpatient | Combination | Not specific |

| Rufo-Campos et al. (2006) [60] | Spain | 62 | To document the usefulness, safety, ease of dosing, and acceptance of oxcarbazepine oral suspension in monotherapy or polytherapy in a large pediatric population of pts | Prospective cohort | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Sarajlija et al. (2013) [61] | Serbia | 35 | To investigate the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in females with Rett syndrome | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Shores (2005) [62] | USA | 16 | To monitor metabolic changes, including hyperprolactinemia, in adolescents medicated with atypical antipsychotics, especially when polypharmacy is involved | Retrospective cohort |

Inpatient | Psychotropic agents |

Psychiatric |

| Sobaniec et al. (2006) [63] | Poland | 90 | To estimate, first, the activity of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase and, second, the malondialdehyde concentration in the erythrocytes in children and adolescents newly diagnosed with epilepsy and receiving either carbamazepine or VPA monotherapy or polytherapy with various AEDs | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Tekgul et al. (2005) [64] | Turkey | 56 | To investigate bone mass density values of ambulatory pediatric pts receiving long term AED treatment + a standard vitamin D3 supplement (400 U/day) | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Thomé-Souza et al. (2003) [65] | Brazil | 28 | To assess the risks and benefits of the co-administration of lamotrigine and VPA in a pediatric population with refractory epilepsy | Retrospective cohort |

Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Unay et al. (2006) [66] | Turkey | 114 | To assess the effects of AEDs on renal tubular function | Cross-sectional | Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Verrotti et al. (1999) [67] | Italy | 84 | To evaluate plasma ammonia levels association with clinical signs and symptoms, plasma carnitine concentrations, and the eventual normalization after VPA withdrawal in a group of children taking VPA | Prospective cohort |

Outpatient | CNS agents | Neurology |

| Wonodi et al. (2007) [68] | USA | 118 | To examine motor side effects associated with the use of antipsychotic drugs in children | Cross-sectional | Outpatient, Inpatient |

Psychotropic agents |

Psychiatric |

ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADR adverse drug reaction, AE adverse event, AED antiepileptic drug, CNS central nervous system, MCID minimally clinically important difference, NR not reported, pts patients, VPA valproic acid/valporate, y year

Discussion

This is the first scoping review which identified outcome measures in pediatric polypharmacy research over the last 27 years. Out of the 363 studies included in this scoping review, 31.4% identified pediatric polypharmacy as an out-come, 73% reported harms, and 22.9% reported benefits. In articles where adverse effects were the outcome measures and polypharmacy the predictor variable, anticonvulsants [31–34, 39, 41–53, 55–57, 60, 61, 63–67] and antipsychotics [36, 37, 41, 48, 54, 58, 62, 68] were among the most common studied groups of CNS medications.

As the number of new medications released into the market continues to increase and the number of published pediatric polypharmacy studies dwindles, there becomes a growing risk for evidence-based practice diversions despite the recognized importance in identifying undesirable outcomes in pediatric polypharmacy [31–68]. Furthermore, because different phrases are often used to define harms throughout the pediatric polypharmacy literature, this may lead to misinterpretation of therapeutic outcomes. The terms ‘adverse event’, ‘adverse drug reaction’, and ‘side effect’ appeared interchangeably in various studies of this scoping review, even though they are not identical terms and may affect the accuracy of clinical judgments [29].

This review revealed that most studies identified polypharmacy as the primary outcome. Typically, these studies evaluated prevalence of pediatric polypharmacy. Although most studies reported on harms associated with polypharmacy, it is important to know that polypharmacy is sometimes necessary and beneficial in treating specific patient cohorts to increase the efficacy of drug therapy or decrease the chance of refractory diseases [69]. As indicated in Table 3, most adverse outcome-related reports examined the effect of polypharmacy in treating neurological diseases such as epilepsy and mood disorder [31–34, 37–39, 41–58, 60–68]. Anticonvulsants, psychotropics, and other CNS medications were among the most common drug categories found in scoping pediatric polypharmacy literature evaluating adverse outcomes. However, only a few reports are currently available that evaluate the effects of combination drug therapy when treating other common conditions such as cardiovascular disease, allergies, infectious diseases, and respiratory disorders in children [70–73].

This scoping review showed that there have not been many publications examining the association between polypharmacy and adverse outcomes, especially outside of psychiatric research. Further, identifying polypharmacy adverse out-comes is important for the determination of pharmacotherapy options, but these outcomes have not been studied extensively in the pediatric polypharmacy literature. Future large longitudinal cohort studies should determine the specific harms and benefits associated with pediatric polypharmacy, especially in vulnerable groups (e.g. patients with newly initiated medications and patients with multiple conditions), and aim to examine which patients benefit from polypharmacy in terms of quality of life, morbidity, and mortality.

Our search strategy consisted of a comprehensive literature search of eight bibliographic databases from their inception. Our transdisciplinary team followed a strict process to decrease inconsistency in data screening and extraction. A few limitations should also be noted. Health insurance status was not reported in the majority of included studies, which may influence the generalizability of these results for all children. Moreover, the lack of standardized medical subject headings, terms, and definitions for polypharmacy is a limiting factor. In accordance with scoping review methodological frameworks, no assessment of quality was performed for included studies, which inherently limits our knowledge about credibility. Of note, many disease states not listed in our findings may use polypharmacy; thus such use was not reported in our research. In addition, we did not synthesize specific information about interventions studied and reviewed within the literature as it is not the intended purpose of a traditional scoping review. Finally, although having a transdisciplinary team from different backgrounds offers various perspectives throughout a scoping review process of this nature and helps to strengthen the approach overall, variability among reviewers is still possible despite a predefined process, tool, and classification plan.

Conclusion

Most studies on pediatric polypharmacy evaluate prevalence, prognosis, or adverse drug reaction-related outcomes, and underscore harms related to polypharmacy. Neurological and psychiatric complex conditions were frequent in those studies reporting adverse drug reactions as an outcome variable. Clinicians should carefully weigh the benefits and harms when deciding to add medications to treatment regimens, especially when these are chronic medications adding to polypharmacy.

Further research is needed to characterize the outcomes related to benefits and harms around polypharmacy for children with comorbidity from various complex chronic conditions both individually and combined. Information gathered from such research will help in the creation of thorough guidelines and pediatric-focused initiatives. Using scoping review methodology allowed us to include a broader range of literature, characterize aims and outcome measures in pediatric polypharmacy studies, and identify existing limitations in research compared with traditional synthesis methodology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledegements

We thank our expert stakeholders whose contribution at different stages of the project improved our research protocol, data quality, interpretation, and reporting: Dr. Joseph Calabrese, Dr. Faye Gary, Dr. Cynthia Fontanella, and Dr. Mai Pham. We are also grateful to Ms. Xuan Ma and Ms. Courtney Baker who conducted a great amount of study screening, data extraction, data cleaning, quality checks, processing, and analysis. This publication was made possible by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative Cleveland, KL2TR000440 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funding body was not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. Dr. Feinstein was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, under award number K23HD091295. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-019-00650-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Dai D, Feinstein JA, Morrison W, et al. Epidemiology of polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions among pediatric patients in ICUs of US children’s hospitals. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(5):218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed B, Nanji K, Mujeeb R, et al. Effects of polypharmacy on adverse drug reactions among geriatric outpatients at a tertiary care hospital in Karachi: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse out-comes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helal SI, Megahed HS, Salem SM, et al. Monotherapy versus polytherapy in epileptic adolescents. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):174–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poudel P, Chitlangia M, Pokharel R. Predictors of poor seizure control in children managed at a tertiary care hospital of Eastern Nepal. Iran J Child Neurol. 2016;10(3):48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasu RS, Iqbal M, Hanifi S, et al. Level, pattern, and determinants of polypharmacy and inappropriate use of medications by village doctors in a rural area of Bangladesh. Clin Outcomes Res. 2014;6:515–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, et al. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug- related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;63(2):187–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinstein J, Dai D, Zhong W, et al. Potential drug-drug interactions in infant, child, and adolescent patients in children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakaki PM, Horace A, Dawson N, et al. Defining pediatric polypharmacy: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0208047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constantine RJ, Boaz T, Tandon R. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of children and adolescents in the fee-for-service component of a large state medicaid program. Clin Ther. 2010;32(5):949–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallego JA, Nielsen J, De Hert M, et al. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11(4):527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lochmann van Bennekom MW, Gijsman HJ, Zitman FG. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in psychotic disorders: a critical review of neurobiology, efficacy, tolerability and cost effectiveness. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(4):327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rashed AN, Wilton L, Lo CCH, et al. Epidemiology and potential risk factors of drug-related problems in Hong Kong paediatric wards: drug-related problems in paediatric patients in Hong Kong. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(5):873–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sammons HM, Choonara I. Learning lessons from adverse drug reactions in children. Children (Basel). 2016. 10.3390/children3010001 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schall CA. A consumer’s guide to monitoring psychotropic medication for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2002;17(4):229–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1001–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saldana SN, Keeshin BR, Wehry AM, et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in children and adolescents at discharge from psychiatric hospitalization. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):836–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golchin N, Isham L, Meropol S, et al. Polypharmacy in the elderly. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4(2):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guthrie B, McCowan C, Davey P, et al. High risk prescribing in primary care patients particularly vulnerable to adverse drug events: cross sectional population database analysis in Scottish general practice. BMJ. 2011;342(7812):1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olashore A, Ayugi J, Opondo P. Prescribing pattern of psychotropic medications in child psychiatric practice in a mental referral hospital in Botswana. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Ferranti S, Ludwig DS. Storm over statins: the controversy surrounding pharmacologic treatment of children. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1309–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hausner E, Fiszman ML, Hanig J, et al. Long-term consequences of drugs on the paediatric cardiovascular system. Drug Saf. 2008;31(12):1083–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, et al. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011;33(1):147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reaction: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000;356(9237):1255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith W Adverse drug reaction: allergy? Side effect? Intolerance? Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(1–2):12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4: software for research synthesis EPPI-Centre Software. London: Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education; 2010. https://eppi. ioe.ac.uk/cms/er4/Features/tabid/3396/Default.aspx Accessed 21 Feb 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Qudah A, Hwang P, Giesbrecht E, et al. Contribution of carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide to neurotoxicity in epileptic children on polytherapy. Jordan Med J. 1991;25(2):171–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allarakhia IN, Garofalo EA, Komarynski MA, et al. Valproic acid and thrombocytopenia in children: a case-controlled retrospective study. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;14(4):303–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amitai M, Sachs E, Zivony A, et al. Effects of long-term valproic acid treatment on hematological and biochemical parameters in adolescent psychiatric inpatients: a retrospective naturalistic study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(5):241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson M, Egunsola O, Cherrill J, et al. A prospective study of adverse drug reactions to antiepileptic drugs in children. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e008298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anghelescu DL, Ross CE, Oakes LL, et al. The safety of concurrent administration of opioids via epidural and intravenous routes for postoperative pain in pediatric oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2008;35(4):412–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bali V, Kamble PS, Aparasu RR. Cardiovascular safety of concomitant use of atypical antipsychotics and long-acting stimulants in children and adolescents with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(2):163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becker EA, Shafer A, Anderson R. Weight changes in teens on psychotropic medication combinations at Austin state hospital. Tex Med. 2005;101(3):62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burch KJ. Using a trigger tool to assess adverse drug events in a children’s rehabilitation hospital. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16(3):204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cramer JA, Steinborn B, Striano P, et al. Non interventional surveillance study of adverse events in patients with epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Las Salas R, Díaz-Agudelo D, Burgos-Flórez FJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions in hospitalized Colombian children. Colomb Med. 2016;47(3):142–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dos Santos DB, Coelho HLL. Adverse drug reactions in hospitalized children in Fortaleza. Brazil. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(9):635–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Khayat H, Shatla H, Ali G, et al. Physical and hormonal profile of male sexual development in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44(3):447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Rashidy OF, Shatla RH, Youssef OI, et al. Cardiac autonomic balance in children with epilepsy: value of antiepileptic drugs. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(4):419–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farhat G, Yamout B, Mikati MA, et al. Effect of antiepileptic drugs on bone density in ambulatory patients. Neurology. 2002;58(9):1348–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galas-Zgorzalewicz B, Borysewicz-Lewicka M, Zgorzalewicz M, et al. The effect of chronic carbamazepine, valproic acid and phenytoin medication on the periodontal condition of epileptic children and adolescents. Funct Neurol. 1996;11(4):187–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghose K, Taylor A. Hypercupraemia induced by antiepileptic drugs. Hum Toxicol. 1983;3:519–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hallioglu O, Okuyaz C, Mert E, et al. Effects of antiepileptic drug therapy on heart rate variability in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2008;79(1):49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hilt RJ, Chaudhari M, Bell JF, et al. Side effects from use of one or more psychiatric medications in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(2):83–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Junger KW, Morita D, Modi AC. The pediatric epilepsy side effects questionnaire: establishing clinically meaningful change. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;45:101–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaplan EH, Kossoff EH, Bachur CD, et al. Anticonvulsant efficacy in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;58:31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim SC, Seol IJ, Kim SJ. Hypohidrosis-related symptoms in pediatric epileptic patients with topiramate. Pediatr Int. 2010;52(1):109–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ko CH, Kong CK, Tse PW. Valproic acid and thrombocytopenia: cross-sectional study. Hong Kong Med J. 2001;7(1):15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwon S, Lee S, Hyun M, et al. The potential for QT prolongation by antiepileptic drugs in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30(2):99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McIntyre RS, Jerrell JM. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse events associated with antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(10):929–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mikati MA, Tarabay H, Khalil A, et al. Risk factors for development of subclinical hypothyroidism during valproic acid therapy. J Pediatr. 2007;151(2):178–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohtahara S, Yamatogi Y. Erratum to “Safety of zonisamide therapy: prospective follow-up survey”. Seizure. 2004;16(1):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Otsuka T, Sunaga Y, Hikima A. Urinary N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase and guanidinoacetic acid levels in epileptic patients treated with anti-epileptic drugs. Brain Dev. 1994;16(6):437–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel A, Chan W, Aparasu RR, et al. Effect of psychopharmacotherapy on body mass index among children and adolescents with bipolar disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rashed AN, Wilton L, Lo CC, et al. Epidemiology and potential risk factors of drug-related problems in Hong Kong paediatric wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(5):873–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rufo-Campos M, Casas-Fernández C, Martínez-Bermejo A. Long-term use of oxcarbazepine oral suspension in childhood epilepsy: open-label study. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(6):480–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sarajlija A, Djuric M, Tepavcevic DK, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Serbian patients with Rett syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):E1972–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shores LE. Normalization of risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia with the addition of aripiprazole. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(3):42–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sobaniec W, Solowiej E, Kulak W, et al. Evaluation of the influence of antiepileptic therapy on antioxidant enzyme activity and lipid peroxidation in erythrocytes of children with epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(7):558–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tekgul H, Dizdarer G, Demir N, et al. Antiepileptic druginduced osteopenia in ambulatory epileptic children receiving a standard vitamin D3 supplement. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18(6):585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomé-Souza S, Freitas A, Fiore LA, et al. Lamotrigine and valproate: efficacy of co-administration in a pediatric population. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28(5):360–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Unay B, Akin R, Sarici SU, et al. Evaluation of renal tubular function in children taking anti-epileptic treatment. Nephrology (Carlton). 2006;11(6):485–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verrotti A, Greco R, Morgese G, et al. Carnitine deficiency and hyperammonemia in children receiving valproic acid with and without other anticonvulsant drugs. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1999;29(1):36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wonodi I, Reeves G, Carmichael D, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in children treated with atypical antipsychotic medications. Mov Disord. 2007;22(12):1777–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmidt D Drug treatment strategies for epilepsy revisited: starting early or late? One drug or several drugs? Epilept Disord. 2016;18(4):356–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jureidini J, Tonkin A, Jureidini E. Combination pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents: prevalence, efficacy, risks and research needs. Pediatr Drugs. 2013;15(5):377–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Papetti L, Nicita F, Granata T, et al. Early add-on immunoglobulin administration in Rasmussen encephalitis: the hypothesis of neuroimmunomodulation. Med Hypotheses. 2011;77(5):917–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gourgari E, Dabelea D, Rother K. Modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease in children with type 1 diabetes: can early intervention prevent future cardiovascular events? Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(12):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li R, Lu L, Lin Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of metronidazole monotherapy versus vancomycin monotherapy or combination therapy in patients with Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0137252 10.1371/journal.pone.0137252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarifying adverse drug events. Documentation and reporting. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jimmy B, Jose J. Patient medication adherence: measures in daily practice. Oman Med J. 2011;26(3):155–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rameekers JG. Behavioural toxicity of medicinal drugs. Practice consequences, incidence and management. Dryg Saf. 1998;18(3):189–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karjalainen EK, Rapasky GA. Molecular changes during acute myeloid leukemia (AML) evolution and identification of novel treatment strategies through molecular stratification. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2016;144:383–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schweitzer I, Tuckwell V, Johnson G. A review of the use of augmentation therapy for the treatment of resistant depression: implications for the clinician. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(3):340–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chaturvedi VP, Mathur AG, Anand AC. Rational drug use: as common as common sense? Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(3):206–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.