Abstract

Eighteen active substances, including 17 organosulfur compounds found in garlic essential oil (T), were identified by GC–MS analysis. For the first time, using the molecular docking technique, we report the inhibitory effect of the considered compounds on the host receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) protein in the human body that leads to a crucial foundation about coronavirus resistance of individual compounds on the main protease (PDB6LU7) protein of SARS-CoV-2. The results show that the 17 organosulfur compounds, accounting for 99.4% contents of the garlic essential oil, have strong interactions with the amino acids of the ACE2 protein and the main protease PDB6LU7 of SARS-CoV-2. The strongest anticoronavirus activity is expressed in allyl disulfide and allyl trisulfide, which account for the highest content in the garlic essential oil (51.3%). Interestingly, docking results indicate the synergistic interactions of the 17 substances, which exhibit good inhibition of the ACE2 and PDB6LU7 proteins. The results suggest that the garlic essential oil is a valuable natural antivirus source, which contributes to preventing the invasion of coronavirus into the human body.

1. Introduction

Garlic (Allium sativum L.) (cf. Figure 1) is considered as an important herb thanks to its variety of uses, including either a common spice for family meals or a popular component in folk-medicine prescriptions.1,2 For thousands of years, garlic has been used as a medication for common colds, influenza, and other kinds of infections.3,4 Recent pharmacological studies indicate that essential oil of garlic is an exceptional source of organosulfur compounds, possessing strong antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer, and antimicrobial properties. The oil is also proven to be conducive to hypoglycemia, hypotension, antithrombotic, immunomodulatory, and prebiotic therapy. Besides, allicin is a typical reactive sulfur species found in the essential oil.5

Figure 1.

Picture of garlic (A. sativum L.).

Recently, many people have been infected with a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), and the death toll has reached thousands and been increasing day by day, which is a major problem in the world.6 Therefore, the demand to seek for natural and safe medicines to prevent coronavirus is of great concern for all scientists around the world. With abundant medicinal resources in Vietnam and the specific healing properties of garlic,7 we herein recommend a solution for the prevention and treatment of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) using the garlic essential oil.

The fact is that coronaviruses belong to a large family of viruses that often cause the common cold in humans. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and lately SARS-CoV-2 are the more severe symptoms caused by the coronavirus family.6,8 SARS-CoV-2 is a new strain that has been unprecedentedly found in humans. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is an integral membrane glycoprotein that is known for the highest expression in most tissues such as kidneys, endothelium, lungs, and heart.9,10 The ACE2 protein is the same functional host-cell receptor shared by SARS-CoV-2 and SARS.8,11,12 The structural database of ACE2 can be referenced from UniProtKB.13 Therefore, besides inhibiting SARS-CoV-2, the inhibition of the ACE2 protein is absolutely necessary to reduce the operability of the host receptor of SARS-CoV-2. If the ACE2 protein is inhibited, it suggests that coronavirus is prevented and treated.12

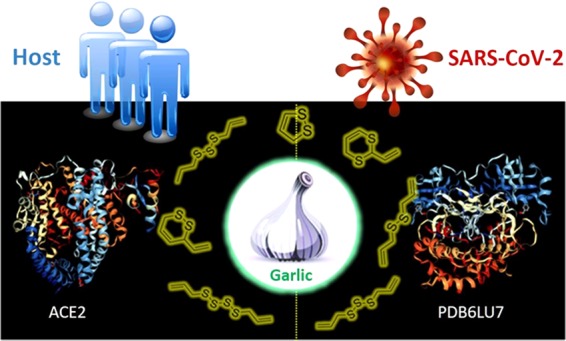

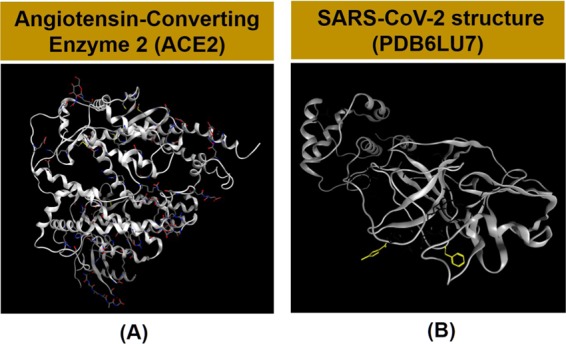

As mentioned above, the high organosulfur compounds in garlic essential oil are expected to have strong interactions with the amino acids of the ACE2 protein. In this study, the idea is to determine the inhibition capacity of ligands in garlic essential oil not only to the ACE2 protein (host receptor for SARS-CoV-2) but also directly to the PDB6LU7 protein (main protease of SARS-CoV-2).14 The structure of the PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2 has been determined recently by Worldwide Protein Data Bank.14 It shows that the two proteins selected from Uniprot and Worldwide Protein Data Bank have three-dimensional structures, as shown in Scheme 1 with the DOI: 10.2210/pdbACE2/pdb presented for the ACE2 protein and the DOI: 10.2210/pdb6LU7/pdb shown for the PDB6LU7 protein in SARS-CoV-2.11−14

Scheme 1. (A) Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the Human Body and (B) PDB6LU7 Protein in SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease.

In this study, garlic essential oil was extracted from commercial garlic and collected in Hue, Vietnam, by steam distillation. The composition of the essential oil was identified by GC–MS. The fact is that the study of HIV-1 resistance to reverse transcriptase inhibitors was reported by Tarasova et al.15 The inhibition abilities of the garlic essential oil toward the ACE2 and PDB6LU7 proteins were determined using the molecular docking technique to investigate the interactions of ligands in the garlic essential oil with the ACE2 and PDB6LU7 proteins. The docking results (i.e., docking score energy (DS), root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), distances, and types of interactions) indicate the inhibitory effects of the compounds in the garlic essential oil on the two proteins. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the inhibitory effects of the considered garlic compounds on the ACE2 protein, which is a crucial foundation about SARS-CoV-2 resistance of those compounds on the main protease (PDB6LU7) protein of SARS-CoV-2 using docking simulations. The results of this study show that natural garlic essential oil is considered as a valuable resource recommended for preventing SARS-CoV-2 invasion into the human body.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Composition of Garlic Essential Oil

The density and refractive index of the garlic essential oil (A. sativum L.) are 1.019 g·mL–1 and 1.467, respectively. The results of the analysis of physicochemical properties in this study agree well with the results (1.025–1.029 g·mL–1; 1.464–1.469) reported by Boukeria et al.16

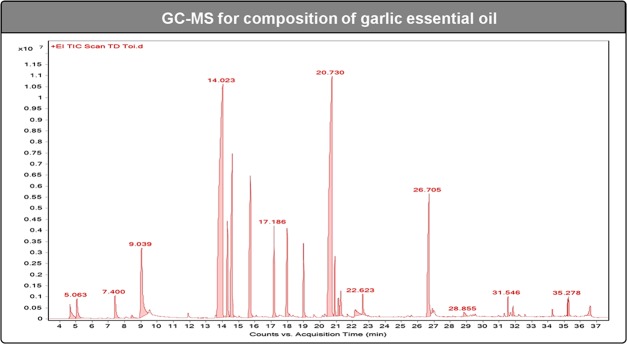

The qualitative and quantitative composition of the garlic essential oil was determined by GC–MS analysis, and the data are recorded in Figure 2 and Table 1, where the compounds are listed in order of their elution. A total of 18 compounds were identified in the garlic essential oil, covering more than 96.6% of the GC–MS profiles. The main constituents in the garlic essential oil were allyl disulfide (28.4%), allyl trisulfide (22.8%), allyl (E)-1-propenyl disulfide (8.2%), allyl methyl trisulfide (6.7%), and diallyl tetrasulfide (6.5%). These results had differences in concentrations of chemical composition compared to those in the previous studies.3,17−19 Li et al. indicated that major essential oil components of garlic from Suzhou City in China were 3-vinyl-4H-1,2-dithiin (31.9%), diallyl trisulfide (13.3%), diallyl sulfide (2.2%), diallyl disulfide (6.9%), propyl allyl disulfide (13.9%), and dimethyl disulfide (7.1%).17 On the contrary, diallyl trisulfide (37.3–45.9%), diallyl disulfide (17.5–35.6%), and methyl allyl trisulfide (7.7–10.4%) were the major components of the garlic essential oil from the state of Ariana (Tunisia).19 The main essential oil components obtained from the east of Algeria were diallyl disulfide (33.4–38.4%) and diallyl trisulfide (23.35–30.0%).20 It has been known that the difference in the chemical composition of essential oils can be attributed to the importance of geo-ecological factors in the production of metabolites of plants.3,17−19

Figure 2.

GC–MS chromatogram of garlic essential oil.

Table 1. Identification of the Bioactive Compounds in Garlic Essential Oil.

Although the bioactivities of garlic essential oil have not been investigated in this study, they were documented in previous studies.21,22 According to Rattanachaikunsopon Pongsak and Parichat Phumkhachorn, allyl disulfide (T1) was also able to inhibit Escherichia coli O157:H7 in a food model.25 Moreover, Wodek et al. indicated that allyl disulfide can constitute a source of sulfane sulfur for liver; therefore, it can be used for cyanide detoxification in mouse tissues.22 Methyl allyl disulfide and diallyl trisulfide were inhibitory agents against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky and Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) for contact toxicity, fumigant toxicity, and antifeedant activity.23 Besides, according to Seki et al., the anticancer effect of diallyl trisulfide on cancer cells HCT-15 and DLD-1 was reported.24 The biological activities of the essential oil depend on the number of sulfur atoms, and the higher the number of sulfur atoms, the stronger the biological activities.19 In this study, the high amount of sulfur (95.63%) in the garlic essential oil suggests a further application of this essential oil in the medicine and pharmaceutical industry.

2.2. Docking Simulation

To the best of our knowledge, there are no results related to SARS-CoV-2 resistance through theoretical and experimental studies of compounds in essential oils.

2.2.1. Docking Simulation Results of Compounds in Garlic Essential Oil into ACE2 Protein

This is our first successful demonstration of the model describing the docking molecules of 17 out of 18 compounds in the garlic essential oil into the complex structures of the ACE2 protein. Docking simulations of the interactions between compounds T1–T17 and the ACE2 protein in the human body are presented as T1-ACE2 to T17-ACE2 in the Supporting Information. We found that T18-ACE2 has the lowest content in the essential oil, and due to its bulky structure, the interaction with the ACE2 protein is not easy; hence, we do not demonstrate its simulation in this study. The results of DS energy and RMSD between compounds in garlic essential oil and proteins with various interactions such as hydrogen bonds, cation−π bonds, π–π bonds, and ionic interactions, as well as the interaction distance between amino acids and the active sites of compounds are presented in Table 2, Figures 3, and S1 (Supporting Information). There are also van der Waals interactions between compounds with other amino acids of the ACE2 protein, but since they are weak interactions, they are not identified in this study.

Table 2. Docking Simulation Results with Docking Score Energy (DS) and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) between Compounds in Garlic Essential Oil and the ACE2 Protein.

| T5 =

T11 > T1 = T2 > T4 > T8 > T9 > T12 > T13 > T14

> T15 > T3 > T7 > T10

> T16 > T17 > T6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | symbol (compound-protein) | DS (kcal·mol–1) | RMSD (Å) | interaction with amino acid |

| allyl disulfide | T1-ACE2 | –12.84 | 1.46 | Pro 565 (2.85 Å), Trp 566 (2.87 Å), Ala 396 (3.14 Å) |

| allyl trisulfide | T2-ACE2 | –12.76 | 1.47 | Gln 102 (2.89 Å; 3.11 Å), Asn 103 (3.45 Å) |

| allyl (E)-1-propenyl disulfide | T3-ACE2 | –9.07 | 0.66 | Glu 208 (3.06 Å), Gly 205 (3.70 Å) |

| allyl methyl trisulfide | T4-ACE2 | –12.50 | 1.56 | Asn 210 (3.13 Å; 3.05 Å), Lys 94 (3.22 Å) |

| diallyl tetrasulfide | T5-ACE2 | –14.06 | 1.23 | Gly 205 (3.43 Å), Asp 206 (2.95 Å), Lys 562 (2.92 Å), Ala 396 (3.82 Å) |

| 1,2-dithiole | T6-ACE2 | –7.89 | 3.09 | Asn 210 (3.29 Å) |

| allyl (Z)-1-propenyl disulfide | T7-ACE2 | –9.04 | 1.58 | Gln 98 (4.14 Å), Glu 208 (3.24 Å) |

| 2-vinyl-4H-1,3-dithiine | T8-ACE2 | –11.83 | 0.62 | Gln 98 (3.10 Å), Val 209 (3.56 Å), Asn 210 (3.93 Å) |

| 3-vinyl-1,2-dithiacyclohex-4-ene | T9-ACE2 | –10.57 | 1.19 | Trp 566 (2.78 Å), Pro 565 (3.95 Å), Glu 208 (3.12 Å) |

| carvone | T10-ACE2 | –8.58 | 1.53 | Lys 94 (2.13 Å), Gln 98 (1.72 Å) |

| trisulfide, 2-propenyl propyl | T11-ACE2 | –14.01 | 1.85 | Trp 566 (3.51 Å), Glu 208 (3.66 Å), (3.05 Å), Val 209 (3.25 Å), Gln 98 (3.52 Å) |

| methyl allyl disulfide | T12-ACE2 | –10.32 | 1.16 | Val 209 (2.31 Å), Gln 98 (3.45 Å), Lys 94 (3.15 Å) |

| diacetonalcohol | T13-ACE2 | –9.71 | 0.85 | Gln 101 (2.13 Å), Asn 210 (1.97 Å; 2.05 Å) |

| trisulfide, (1E)-1-propenyl 2-propenyl | T14-ACE2 | –9.57 | 0.68 | Asn 210 (3.20 Å; 1.72 Å), Ser 563 (3.73 Å) |

| allyl sulfide | T15-ACE2 | –9.38 | 1.48 | Asn 210 (2.31 Å), Lys 94 (3.15 Å), Gln 98 (3.45 Å) |

| 1-propenyl methyl disulfide | T16-ACE2 | –8.06 | 0.88 | Asp 206 (2.81 Å), Trp 566 (3.46 Å) |

| trisulfide, (1Z)-1-propenyl 2-propenyl | T17-ACE2 | –8.06 | 2.35 | Glu 208 (3.29 Å), Gln 98 (3.64 Å) |

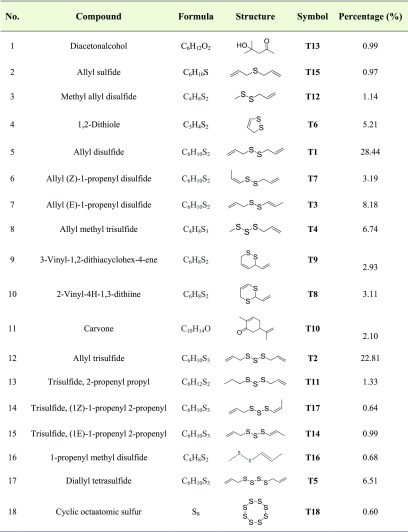

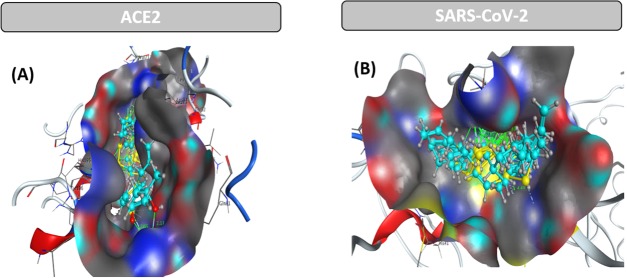

Figure 3.

(A) Native human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) crystal structure. Docking simulation of the interaction between compounds T5, T11, T1, T2, T4, and the ACE2 protein in the human body: (B) T5-ACE2, (C) T11-ACE2, (D) T1-ACE2, (E) T2-ACE2, and (F) T4-ACE2. The inhibitory effects of the compounds on the ACE2 protein are of the order: T5 ≈ T11 > T1 ≈ T2 > T4.

The model describing the docking molecules indicated that all of the 17 compounds in the garlic essential oil from T1-ACE2 to T17-ACE2 have the binding ability toward the areas affected by the ACE2 protein. The five presented representatives T5-ACE2, T11-ACE2, T1-ACE2, T2-ACE2, and T4-ACE2 have good DS energies of −14.06, −14.01, −12.84, −12.76, and −12.5 kcal·mol–1, respectively (cf. Table 2 and Figure 3). It can be seen that T5-ACE2 interacts best with regions of the ACE2 protein, and the same trend is found for T11-ACE2. The priority order of the interactions of compounds in the garlic essential oil was as follows: T5 = T11 > T1 = T2 > T4 > T8 > T9 > T12 > T13 > T14 > T15 > T3 > T7 > T10 > T16 > T17 > T6.

We found that the sulfur compounds had strong interactions with amino acids in the ACE2 protein. It is revealed from the results of the model describing the docking molecules that the relation in terms of structure and inhibition ability of the 17 substances in the garlic essential oil toward the ACE2 protein was as follows: the compounds had very strong interactions with the amino acids Pro 565, Trp 566, Ala 396, Gln 102, Gln 101, Glu 208, Gly 205, Gln 98, Asn 210, Lys 94, Lys 562, Val 209, and Ser 563. The interactions mainly took place with the molecule groups containing sulfur in their compounds. Interestingly, T10-ACE2 and T13-ACE2 mainly interacted with oxygen in the compounds. The total content of the 17 compounds in the garlic essential oil resistant to the ACE2 protein was 99.4%. This proves that the entire essential oil is appropriate for the prevention and treatment of pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2. Thus, finding active sites of compounds in the essential oil to inhibit the ACE2 protein is of great significance to the orientation of using the garlic essential oil in the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 in specific and other viruses causing flu or pneumonia in general.

2.2.2. Docking Results of Compounds in Garlic Essential Oil into the PDB6LU7 Protein of SARS-CoV-2

The model describing the docking molecules of 18 substances in the garlic essential oil into the complex structure of the PDB6LU7 protein was constructed using MOE 2015.10 software. The docking was successful in 17 compounds of T1-SARS-CoV-2 to T17-SARS-CoV-2. The DS energy and RMSD values between ligands and proteins shown through hydrogen bonds, cation−π bonds, π–π bonds, and ionic interactions, as well as the interaction distance between amino acids and the active sites in the title molecules are presented in Table 3 and Figures 4 and S2 (Supporting Information).

Table 3. Docking Simulation Results with Docking Score Energy (DS) and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) between the Title Compounds and PDB6LU7 Protein of SARS-CoV-2.

| T2 =

T1 > T5 > T4 > T11 > T15 > T8 > T16 > T9 >

T12 > T13 > T3 > T6 > T7

> T10 > T14 > T17 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | symbol (compound-protein) | DS (kcal·mol–1) | RMSD (Å) | interaction with amino acid |

| allyl disulfide | T1-SARS-CoV-2 | –15.32 | 1.35 | Gly 143 (2.59 Å), Asn 142 (2.92 Å), Leu 141 (2.94 Å), Cys 145 (2.98 Å), Ser 144 (3.15 Å), His 163 (2.95 Å) |

| allyl trisulfide | T2-SARS-CoV-2 | –15.02 | 0.66 | Gly 143 (3.93 Å; 2.79 Å), Asn 142 (2.87 Å; 2.67 Å), Cys 145 (3.25 Å; 3.63 Å), Ser 144 (3.06 Å) |

| allyl (E)-1-propenyl disulfide | T3-SARS-CoV-2 | –13.25 | 1.49 | Leu 141 (2.98 Å), Ser 144 (3.07 Å) |

| allyl methyl trisulfide | T4-SARS-CoV-2 | –14.36 | 1.37 | Gly 143 (3.69 Å), Asn 142 (2.81 Å), Cys 145 (3.61 Å; 3.12 Å), Ser 144 (2.96 Å) |

| diallyl tetrasulfide | T5-SARS-CoV-2 | –14.47 | 0.94 | Gly 143 (2.88 Å; 2.98 Å), Asn 142 (2.10 Å), Cys 145 (3.94 Å; 3.56 Å), Ser 144 (3.14 Å) |

| 1,2-dithiole | T6-SARS-CoV-2 | –13.21 | 2.30 | Asn 142 (3.75 Å), Cys 145 (3.75 Å) |

| allyl (Z)-1-propenyl disulfide | T7-SARS-CoV-2 | –12.60 | 1.72 | Gly 143 (3.32 Å), Leu 141 (3.62 Å) |

| 2-vinyl-4H-1,3-dithiine | T8-SARS-CoV-2 | –14.04 | 4.35 | Gly 143 (2.73 Å), Asn 142 (3.82 Å), Cys 145 (3.11 Å), Ser 144 (3.02 Å) |

| 3-vinyl-1,2-dithiacyclohex-4-ene | T9-SARS-CoV-2 | –13.83 | 1.05 | Glu 166 (2.86 Å), Met 165 (2.88 Å), Cis 145 (2.13 Å) |

| carvone | T10-SARS-CoV-2 | –12.36 | 1.62 | His 163 (2.15 Å) |

| trisulfide, 2-propenyl propyl | T11-SARS-CoV-2 | –14.36 | 1.37 | Gly 143 (2.62 Å; 2.81 Å), Asn 142 (2.85 Å), Cys 145 (3.15 Å; 3.50 Å), Ser 144 (2.87 Å), His 163 (2.97 Å) |

| methyl allyl disulfide | T12-SARS-CoV-2 | –13.56 | 1.51 | Cys 145 (2.43 Å), Ser 144 (2.82 Å), His 163 (2.65 Å) |

| diacetonalcohol | T13-SARS-CoV-2 | –13.26 | 1.41 | Cys 145 (2.93 Å), Ser 144 (2.26 Å) |

| trisulfide, (1E)-1-propenyl 2-propenyl | T14-SARS-CoV-2 | –12.00 | 2.12 | Leu 141 (3.32 Å), Ser 144 (2.39 Å) |

| allyl sulfide | T15-SARS-CoV-2 | –14.24 | 1.20 | Gly 143 (2.75 Å), Asn 142 (2.75 Å), Leu 141 (3.56 Å), Cys 145 (3.47 Å), Ser 144 (3.32 Å) |

| 1-propenyl methyl disulfide | T16-SARS-CoV-2 | –13.84 | 0.91 | Gly 143 (2.89 Å), Asn 142 (3.88 Å), Cys 145 (2.83 Å), Ser 144 (2.80 Å) |

| trisulfide, (1Z)-1-propenyl 2-propenyl | T17-SARS-CoV-2 | –11.68 | 3.60 | Leu 141 (3.38 Å) |

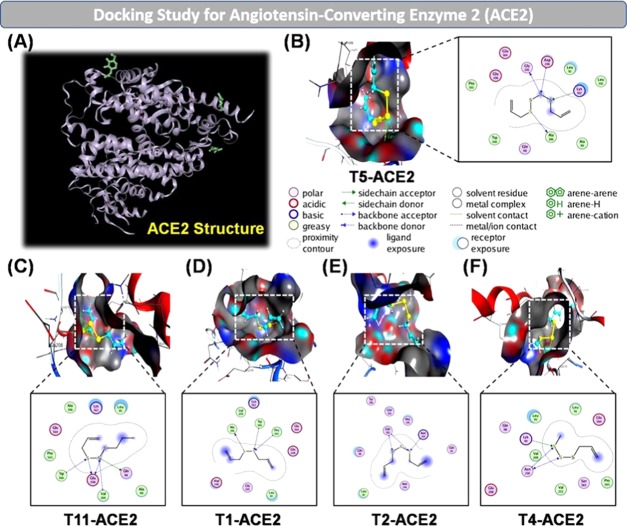

Figure 4.

(A) Crystal structure of the virus main protease in the complex (PDB6LU7). Docking simulation of the interaction between compounds T1, T2, T4, T5, and T11, and the PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2: (B) T1-SARS-CoV-2, (C) T2-SARS-CoV-2, (D) T4-SARS-CoV-2, (E) T5-SARS-CoV-2, and (F) T11-SARS-CoV-2. The inhibitory effects of the compounds on the PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2 were of the order: T1 ≈ T2 > T5 > T4 > T11.

The anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of the garlic essential oil composition into the PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2 was found in the following order: T2 = T1 > T5 > T4 > T11 > T15 > T8 > T16 > T9 > T12 > T13 > T3 > T6 > T7 > T10 > T14 > T17. The compounds T1 and T2 indicated the highest content in the garlic essential oil (51.3%) and gave the best anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity, followed by the three compounds T5, T4, and T11. These five substances account for 65.83% composition of the garlic essential oil (Figure 4). The results demonstrated that these 17 compounds have a stronger inhibition on PDB6LU7 of SARS-CoV-2 than that on the ACE2 protein in the human body. The DS energy was negative, in the range of −15.32 to −11.68 kcal·mol–1. Interactions with amino acid included Pro 565, Gln 102, Glu 208, Asn 210, Gly 205, Gln 98, Trp 566, Lys 94, Val 209, Gln 101, Asp 206, Asn 103, Ser 563, Ala 396, and Lys 562. The total content of 17 out of 18 compounds in the garlic essential oil exhibiting inhibition ability toward the PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2 is 99.4%. The docking simulation results are excellent evidence of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of the garlic essential oil.

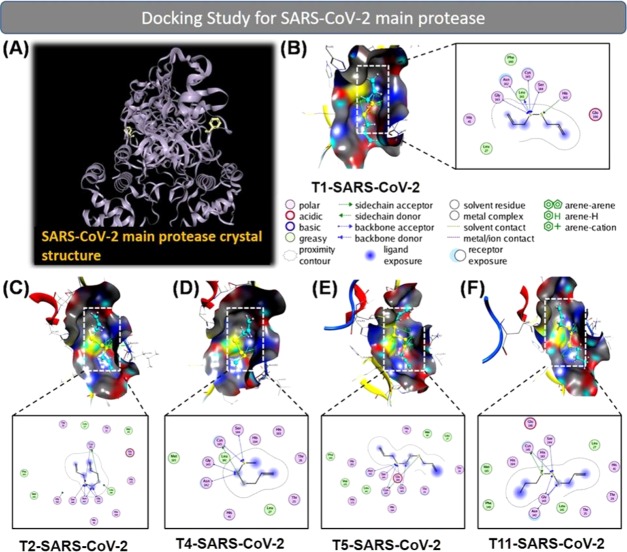

The simultaneous interaction of 17 out of 18 compounds in the garlic essential oil with the ACE2 protein and the PDB6LU7 protein is described in Figure 5. Hydrogen bonds, cation−π bonds, π–π bonds, and ionic interactions of 17 compounds with the amino acids of the ACE2 protein included Trp 566, Asn 103, Gly 205, Lys 94, Asp 206, Glu 208, Val 209, Pro 565, Asn 210, Ser 563, Gln 98, Gln 102, Gln 101, Ala 396, Lys 562, and Ala 396, and those with the amino acids of the PDB6LU7 protein included Gly 143, Glu 166, Asn 142, Leu 141, Cys 145, Ser 144, His 163, and Met 165. Based on the percentage of each compound in the garlic essential oil (shown by GC–MS) and docking score (DS) energy of each compound, the average DS energies of these 17 compounds with the ACE2 protein and the PDB6LU7 protein were calculated as −11 311 and −13 871 kcal·mol–1, respectively. This shows an excellent result to confirm the effects of the garlic essential oil on the virus host receptor (ACE2) inhibition and SARS-CoV-2 resistance. Therefore, it is possible to use each compound in garlic essential oil or the whole essential oil system to act simultaneously on the ACE2 protein and the PDB6LU7 protein. This result opens the direction of research and application of the essential oils in general, garlic essential oil in particular, in the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 5.

3D-docking results with simultaneous interaction of all 17 substances (17T = T1–T17) in the garlic essential oil with (A) ACE2 protein and (B) PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2.

3. Conclusions

This study proposes a potential approach to the use of natural essential oils, in general, and garlic essential oil, in particular, to tackle the current pandemic SARS-CoV-2. The compounds in the garlic essential oil inhibit the ACE2 protein, leading the virus to lose the host receptor and attacking the PDB6LU7 protein—the main protease of SARS-CoV-2—at the same time. This prevents protein maturation of the virus and the spread of infection. Docking simulation suggests the active binding site of most active compounds in garlic essential oil with the ACE2 protein and the PDB6LU7 protein. From the analysis of the docking data, it is revealed that 17 (T1–T17) out of 18 compounds of the garlic essential oil are capable of inhibiting ACE2 and resisting SARS-CoV-2 and that the total content of these 17 compounds accounts for 99.4% composition of the garlic essential oil. The docking score (DS) energy of compounds for the ACE2 protein ranges from −14.06 to −7.89 kcal·mol–1, and the DS energy of compounds for the PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2 ranges from −15.32 to −11.68 kcal·mol–1. The order of active compounds inhibiting the ACE2 protein is as follows: T5 = T11 > T1 = T2 > T4 > T8 > T9 > T12 > T13 > T14 > T15 > T3 > T7 > T10 > T16 > T17 > T6. Meanwhile, the order of active compounds resisting SARS-CoV-2 is T2 = T1 > T5 > T4 > T11 > T15 > T8 > T16 > T9 > T12 > T13 > T3 > T6 > T7 > T10 > T14 > T17. The synergistic interactions of 17 substances of the garlic essential oil exhibited good inhibition on the ACE2 protein (host receptor of the virus) and the PDB6LU7 protein of the virus. This study opens the door toward the use of the garlic essential oil in discovering and treating SARS-CoV-2 to prevent the current pandemic.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experiment

4.1.1. Sample Collection

Garlic (A. sativum L.) was purchased from a local market (Thua Thien Hue province in Central Vietnam). Then, it was botanically identified, and a voucher specimen was deposited at the Department of Biology, University of Sciences, Hue University. During the experiment, all of the samples were maintained in our lab at appropriate conditions (e.g., 25 °C in the dark).

4.1.2. Chemicals and Equipment

All analytical-grade chemicals obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. were used without any further purification. The major equipment includes a hydrodistillation apparatus (Merck Specialities Pvt. Ltd., India), a polarimeter (Reichert Cat #14003000), a Jasco V-630 spectrophotometer (Japan), and a gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) device (Aligent GC 7890B-MS 5975C).

4.1.3. Isolation of Essential Oil

A hydrodistillation Clevenger apparatus was used to extract the garlic essential oil. Peeled garlic (250 g) was minced and then put into a 1 L flask, in which 400 mL of distilled water was added. The essential oil was obtained by water distillation at 100 °C for 90 min, according to the Vietnamese Pharmacopoeia.25 A sterilized glass vial was used to collect the essential oil. The essential oil was dried by anhydrous Na2SO4 before being stored at 4 °C for further analysis. The extraction process was repeated three times to check the repeatability of the analytical procedure.25

4.1.4. Refractive Index and Density of the Essential Oil

Refractive index and density are two common physical parameters for checking essential oil composition and purity. The refractive index of essential oils was determined using a polarimeter, and the density of the essential oil was determined using a pycnometer flask according to the Vietnamese Pharmacopoeia25 and Boukeria et al.16

4.1.5. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) Analysis

An Agilent GC 7890B-MS 5975C instrument combined with an HP-5MS column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) was used to identify the chemical composition of the garlic essential oil. The utilized carrier gas was helium at constant pressure (13 psi). The essential oil (1 μL) was injected into the GC with a split ratio of 20:1. The injection temperature was 250 °C. The column temperature program was applied as follows: start at 70 °C and then increased at the rate of 10 °C every minute until it reached 280 °C. After the analytes were separated on a capillary column, they passed through the ionization zone in the MS source (ionization energy: 70 eV; interface temperature: 280 °C; MS temperature: 230 °C; quadrupole temperature: 150 °C), and the neutral molecules were ionized yielding specific mass/charge (m/z) ratios. C8–C30 Alkanes Calibration Standard (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to identify unknown compounds through their retention indices by comparing their mass spectra to those contained in the NIST02 database. The concentration of each analyte will be calculated based on its peak area in the chromatogram.

4.2. Molecular Docking Simulation

The molecular docking technique is used to predict and describe the interaction (including the binding energy and structural parameters) of compounds resistant to the ACE2 protein in the human body and the PDB6LU7 protein in SARS-CoV-2. The docking results reveal that there are potential compounds in the essential oil to prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2. The molecular docking modeling consists of five essential steps15,26−28 as follows:

Step 1: Selection of proteins

Selection of proteins in PDB: The biological targets are the ACE2 protein and the PDB6LU7 protein presented at Uniprot13 and Worldwide Protein Data Bank.14

Determination of bonding position: The protein action areas were determined based on the ligand positions within a radius of 4.5 Å and the presence of important amino acids. Water molecules were removed, and the structures of amino acids were checked before reestablishing the enzyme action areas.

Step 2: Preparation of proteins

Creating 3D structures: The 2D chemical structure (flat structure) of the compounds was automatically converted to the 3D chemical structure (three-dimensional structure) by ChemBioOffice 2018 software.

Lowest-energy state: The 3D molecular structures of the compounds were then optimized using SYBYL-X 1.1 software with the purpose to correct the mismatch values of bond lengths, bond angles, bending angles, and unusual nonbonding interactions due to the atoms in different parts of the compounds occupying the same space. The energy minimization program used the Conj Grad method (conjugate gradient) to choose the stop point where the energy change is less than the cutoff value of 0.001 kcal·mol–1 with partial charges of Gasteiger–Huckel and the maximum number of iterations needed was 10 000. This method accumulates the information about the energy function from each iteration, which is suitable for small and large molecules. Molecular dynamics conduction was used to obtain the structures with the lowest energy via the principle of simulated annealing in Sybyl-X 1.1 software. The molecular structure was heated at a high temperature (700 K) for a certain time (1000 ps) so that the molecule rearranges its current state and then cooled to 200 K for another 1000 ps to a steady state for computing the final configuration. The program automatically iterated five times to find the various configurations needed, and then the minimized energy was observed again to determine steric energy. In this way, the structural parameters of compounds with different energies were found, which were more durable than the original structures.

Step 3: Redocking

Redocking of protein-compound cocrystal structures: the redocking of protein–ligand complex cocrystal structures aims to assess the suitability of docking parameters. The process was carried out with three structures of compounds as follows:

-

(1)

Separation of compounds from homogenized complexes in proteins.

-

(2)

Separation of compounds from homogeneous complexes and repreparation using Sybyl-X 1.1 software.

-

(3)

Preparation of new compounds (structure drawing, structural optimization parameters on minimal energy, molecular dynamics calculations).

Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values reflect the deviation of compounds’ structures after docking compared to available structures in the crystal structure and comparing the interactions of compounds in the crystal structure after docking. The docking results are considered reliable when the RMSD value is <1.5 Å, and the interactions between compounds and the initial enzyme are not significantly different.

Step 4: Molecules docking into protein: docking investigations

Docking of compounds into prepared proteins and compounds via conducting the docking process with MOE 2015.10 software with the following options: the method of placing compound fragments into the triangle matching; the maximum number of results for each iteration is 1000; the maximum number of results for each compound fragmentation is 200; retain the five best configurations of each compound in the bonding complex for further analysis. The best configuration is the one with the lowest docking score (DS) energy (kcal·mol–1). This score is the total energy consumed for the formation of bonding interactions between the compounds and the two proteins selected.

Step 5: Docking results analysis

Evaluation of docking score (DS): Analysis of the interactions between the compounds and targeted proteins, and performance of interaction on 2D and 3D planes using MOE 2015.10 software. Various interactions, such as van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, cation−π bonds, π–π bonds, and ionic interactions, and the interaction distance between amino acids and the active sites of compounds are plotted. Van der Waals interactions are detected by contact with hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces between the compounds and the bonding point.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED). The authors would like to thank Prof. Jong Seung Kim (Korea University) for his valuable comments and discussion. Also, they highly appreciate Dr Mingle Li (Korea University) and Khue Lai (IU) for helping with figure preparation.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00772.

Docking simulation of the interaction between compounds and the ACE2 protein in human body; inhibitory effects of compounds on the ACE2 protein: T8 > T9 > T12 > T13 > T14 > T15 > T3 > T7 > T10 > T16 > T17 > T6; docking simulation of the interaction between compounds and the PDB6LU7 protein of SARS-CoV-2; and inhibitory effects of compounds on the PDB6LU7 protein: T15 > T8 > T16 > T9 > T12 > T13 > T3 > T6 > T7 > T10 > T14 > T17 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Satyal P.; Craft J. D.; Dosoky N. S.; Setzer W. N. The chemical compositions of the volatile oils of garlic (Allium sativum) and wild garlic (Allium vineale). Foods 2017, 6, 63. 10.3390/foods6080063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung L. Y. The antioxidant properties of garlic compounds: allyl cysteine, alliin, allicin, and allyl disulfide. J. Med. Food 2006, 9, 205–213. 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najjaa H.; Neffati M.; Zouari S.; Ammar E. Essential oil composition and antibacterial activity of different extracts of Allium roseum L., a North African endemic species. C. R. Chim. 2007, 10, 820–826. 10.1016/j.crci.2007.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romeilah R. M.; Fayed S. A.; Mahmoud G. I. Chemical compositions, antiviral and antioxidant activities of seven essential oils. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2010, 6, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chekki R. Z.; Snoussi A.; Hamrouni I.; Bouzouita N. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Tunisian garlic (Allium sativum) essential oil and ethanol extract. Mediterr. J. Chem. 2014, 3, 947–956. 10.13171/mjc.3.4.2014.09.07.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of 2019-nCoV—a quick overview and comparison with other emerging viruses. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 69–71. 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. C.; Chu T. A. P.; Van Nguyen H. In vitro evaluation of antibacterial activity of garlic Allium sativum against poultry pathogens and effect of garlic supplementation on ducking growth performance. Vietnam J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 57, 9. 10.15625/2525-2518/57/3B/14045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tipnis S. R.; Hooper N. M.; Hyde R.; Karran E.; Christie G.; Turner A. J. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 33238–33243. 10.1074/jbc.M002615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikellis C.; Thomas M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a key modulator of the renin angiotensin system in health and disease. Int. J. Pept. 2012, 2012, 256294 10.1155/2012/256294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A.; Deming D.; Paddock C. D.; Cheng A.; Yount B.; Vogel L.; Herman B. D.; Sheahan T.; Heise M.; Genrich G. L.; et al. A mouse-adapted SARS-coronavirus causes disease and mortality in BALB/c mice. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e5 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralinski L. E.; Menachery V. D. Return of the Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV. Viruses 2020, 12, 135. 10.3390/v12020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevis D.; Kostaki E. G.; Magiorkinis G.; Panayiotakopoulos G.; Sourvinos G.; Tsiodras S. Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel corona virus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event. Infect., Genet. Evol. 2020, 79, 104212 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homo Sapiens (Human). https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9BYF1.

- The crystal structure of COVID-19 main protease in complex with an inhibitor N3. https://www.wwpdb.org/pdb?id=pdb_00006lu7. Initial deposition on 26 January 2020.

- Tarasova O.; Poroikov V.; Veselovsky A. Molecular docking studies of HIV-1 resistance to reverse transcriptase inhibitors: Mini-review. Molecules 2018, 23, 1233. 10.3390/molecules23051233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukeria S.; Kadi K.; Kalleb R.; Benbott A.; Bendjedou D.; Yahia A. Phytochemical and physicochemical characterization of Allium sativum L. and Allium cepa L. Essential oils. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016, 7, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Chen W. C.; Wang W. P.; Tian W. Y.; Zhang X. G. Extraction of essential oils from garlic (Allium sativum) using ligarine as solvent and its immunity activity in gastric cancer rat. Med. Chem. Res. 2010, 19, 1092–1105. 10.1007/s00044-009-9255-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed H. S.; Chizzola R.; Ramadan A. A.; Edris A. E. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of garlic essential oils evaluated in organic solvent, emulsifying, and self-microemulsifying water based delivery systems. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 196–204. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziri S.; Casabianca H.; Hanchi B.; Hosni K. Composition of garlic essential oil (Allium sativum L.) as influenced by drying method. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2014, 26, 91–96. 10.1080/10412905.2013.868329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boubechiche Z.; Chihib N.-E.; Jama C.; Hellal A. Comparison of Volatile Compounds Profile and Antioxydant Activity of Allium sativum Essential Oils Extracted using Hydrodistillation, Ultrasound-Assisted and Sono-Hydrodistillation Processes. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2017, 51, S281–S285. 10.5530/ijper.51.3s.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rattanachaikunsopon P.; Phumkhachorn P. Diallyl sulfide content and antimicrobial activity against food-borne pathogenic bacteria of chives (Allium schoenoprasum). Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 2008, 72, 2987–2991. 10.1271/bbb.80482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- W3odek L. Allyl disulfide as donor and cyanide as acceptor of sulfane sulfur in the mouse tissues. Pharmacol. Rep. 2005, 57, 212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Chen S. X.; Ho S. H. Bioactivities of methyl allyl disulfide and diallyl trisulfide from essential oil of garlic to two species of stored-product pests, Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2000, 93, 537–543. 10.1603/0022-0493-93.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T.; Hosono T.; Hosono-Fukao T.; Inada K.; Tanaka R.; Ogihara J.; Ariga T. Anticancer effects of diallyl trisulfide derived from garlic. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17, 249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vietnamese Pharmacopoeia; Medical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Babu T. M. C.; Rajesh S. S.; Bhaskar B. V.; Devi S.; Rammohan A.; Sivaraman T.; Rajendra W. Molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, biological evaluation and 2D QSAR analysis of flavonoids from Syzygium alternifolium as potent anti-Helicobacter pylori agents. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 18277–18292. 10.1039/C6RA27872H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo T. D.; Tran T. D.; Le M. T.; Thai K. M. Computational predictive models for P-glycoprotein inhibition of in-house chalcone derivatives and drug-bank compounds. Mol. Diversity 2016, 20, 945–961. 10.1007/s11030-016-9688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai K. M.; Le D. P.; Tran T. D.; Le M. T.; et al. Computational assay of Zanamivir binding affinity with original and mutant influenza neuraminidase 9 using molecular docking. J. Theor. Biol. 2015, 385, 31–39. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.