Abstract

Introduction

The management of advanced prostate cancer (PCa) continues to evolve with the emergence of new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. As a result, there are multiple areas in this landscape with a lack of high-level evidence to guide practice. Consensus initiatives are an approach to establishing practice guidance in areas where evidence is unclear. We conducted a Canadian-based consensus forum to address key controversial areas in the management of advanced PCa.

Methods

As part of a modified Delphi process, a core scientific group of PCa physicians (n=8) identified controversial areas for discussion and developed an initial set of questions, which were then reviewed and finalized with a larger group of 29 multidisciplinary PCa specialists. The main areas of focus were non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC), metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC), metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), oligometastatic prostate cancer, genetic testing in prostate cancer, and imaging in advanced prostate cancer. The predetermined threshold for consensus was set at 74% (agreement from 20 of 27 participating physicians).

Results

Consensus participants included uro-oncologists (n=13), medical oncologists (n=10), and radiation oncologists (n=4). Of the 64 questions, consensus was reached in 30 questions (n=5 unanimously). Consensus was more common for questions related to biochemical recurrence, sequencing of therapies, and mCRPC.

Conclusions

A Canadian consensus forum in PCa identified areas of agreement in nearly 50% of questions discussed. Areas of variability may represent opportunities for further research, education, and sharing of best practices. These findings reinforce the value of multidisciplinary consensus initiatives to optimize patient care.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the leading causes of cancer-mortality in men.1 Despite recent advances in the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for management of PCa, there are still multiple areas in this landscape deficient of high-level evidence to guide practice. A multidisciplinary consensus approach can provide guidance in areas where evidence is lacking or unclear.2 A Canadian-based consensus forum to address key controversial areas in the management of advanced prostate cancer was conducted.

Methods

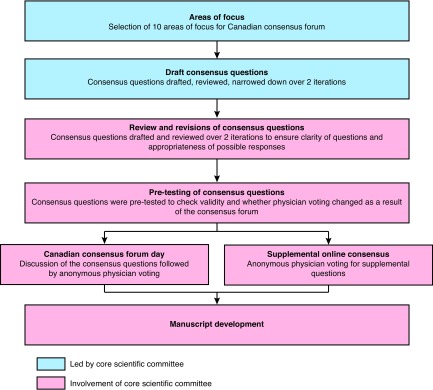

We used a modified Delphi process for the Canadian consensus forum (Fig. 1), modelled after other global consensus initiatives. First, a core scientific group of eight multidisciplinary prostate cancer expert physicians (steering committee) identified the key areas of focus for the consensus forum, and then drafted the initial set of consensus questions. After completing more than two rounds of review, questions were refined, and the number of questions was reduced.

Fig. 1.

The modified Delphi process used for the consensus forum.

Second, a panel of 29 Canadian multidisciplinary PCa specialists, including the members of the steering committee, was invited to review and provide feedback on the draft questions. The panel refined each question and set of responses.

At the completion of the review period, 64 questions were prioritized for the day of the consensus forum and 50 questions delegated to the supplemental online consensus process. The panel was invited to participate in the pre-testing of the consensus questions.

On the day of the consensus forum, the core scientific group led the panel of 27 clinicians in discussion, debate, and clarification of questions before anonymous voting. Two members of the 29-member panel were unable to join the consensus voting forum day. The predetermined threshold for consensus was set at 74% (agreement from 20 of 27 participating physicians), similar to other consensus initiatives.2–4 In deliberating their answers, participants agreed no barriers to treatment access would be assumed. Where appropriate, the panel determined if there was a need to repeat the vote on a question following clarification or refinement of the question.5–7

The supplemental questions underwent consensus voting during the week following the forum day via an online survey.

Results

The main areas of focus selected for the forum were as follows:

Biochemical recurrence following local definitive therapy

Non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC)

Metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC)

Sequencing of systemic treatments

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC)

Oligometastatic prostate cancer

Access and funding of treatments

Genetic testing in prostate cancer

Referrals for care

Imaging in advanced prostate cancer

The consensus forum was comprised of urologists (n=13, 48%), medical oncologists (n=10, 37%), and radiation oncologists (n=4, 15%). Geographic representation spanned British Columbia and Alberta (n=7, 26%), Ontario (n=15, 56%), and Quebec and Atlantic Canada (n=5, 19%) (Supplementary Table 1). Most panel participants had been in practice for more than 10 years (n=17, 64%).

In general, of the 64 questions that underwent anonymous in-person electronic voting at the forum, consensus was reached in 30, with unanimous voting in five questions (Table 1). Group moderated discussions followed the voting for each question. Eight questions underwent revoting after either clarifying discussion or question refinements. Question 7 was eliminated after it was deemed no longer relevant after question revision. One question was added during the consensus forum (Q22b) (Supplementary Appendix; available at cuaj.ca). Consensus was more common for questions related to biochemical recurrence, sequencing of therapies, and mCRPC and less common for oligometastatic prostate cancer, mCSPC, and nmCRPC (Supplementary Table 2). The voting results for each question are available in the separate Supplementary Appendix section (see cuaj.ca).

Table 1.

Areas of consensus (>74%) at PCa consensus forum

| Biochemical recurrence | |

|

| |

| In general, absolute PSA should be used to guide when to initiate ADT after biochemical recurrence following local radical treatment. | 89% |

| Intermittent ADT should generally be used for patients with no documented metastatic disease and PSA-only recurrence following local radical treatment. | 92.6% |

| On average, PSA should be measured every 3–4 months for PSA recurrence after local radical therapy. | 92.6% |

|

| |

| nmCRPC | |

|

| |

| For most patients, a PSADT of <10 months should be used as the threshold to start second-generation AR therapy for patients with nmCRPC. | 78% |

| For most patients, a PSADT of <10 months should be used as the threshold to start second-generation AR therapy for patients with nmCRPC and PSA 10–20 ng/mL. | 88.9% |

| For patients with nmCRPC on conventional imaging and PSADT <10 months, treatment should be initiated with nmCRPC agents, such as apalutamide or enzalutamide. | 96.3% |

| For most patients with nmCRPC on conventional imaging, metastases on PET-based imaging, and PSADT <10 months, treatment with nmCRPC agents, such as apalutamide or enzalutamide, is recommended. | 88.9% |

| Surrogate endpoints likely correlated with OS, such as MFS, provide sufficient evidence for treatment decision-making in nmCRPC. | 100% |

|

| |

| mCSPC | |

|

| |

| For most men presenting with high-volume mCSPC, ADT treatment in the form of LHRH agonist alone (± short course firstgeneration AR antagonist) is recommended. | 81.5% |

| For most patients with de novo, low-volume mCSPC who are not symptomatic from the primary tumor, treatment of the primary tumor is recommended, in addition to systemic therapy. | 74.1% |

| For most patients with de novo, low-volume mCSPC, radiation therapy is the preferred form of treatment of the primary tumor. | 96.3% |

| In men with de novo, high-volume mCSPC who are not symptomatic from the primary tumor, treatment of the primary tumor, in addition to systemic therapy is not recommended. | 78% |

|

| |

| Sequencing of treatments across the disease spectrum | |

|

| |

| In patients who receive apalutamide for nmCRPC and subsequently progress to mCRPC, docetaxel is recommended for firstline treatment of mCRPC (with or without stereotactic body radiotherapy). | 81.5% |

| In patients who receive enzalutamide for nmCRPC and subsequently progress to mCRPC, docetaxel is recommended for firstline treatment of mCRPC (with or without stereotactic body radiotherapy). | 85.2% |

| For most asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic men who received docetaxel in the castration-sensitive setting, abiraterone acetate + prednisone or enzalutamide is the preferred first-line treatment option for mCRPC. | 100% |

| For most asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic men who received abiraterone acetate + prednisone in the castrationsensitive setting, docetaxel is the preferred first-line treatment option for mCRPC. | 78% |

| For most symptomatic men who received abiraterone acetate + prednisone in the castration-sensitive setting, docetaxel is the preferred first-line treatment option for mCRPC. | 96.2% |

| For most asymptomatic men who were treated with abiraterone acetate + prednisone or enzalutamide for first-line mCRPC and who had an initial response followed by PSA-only progression (secondary acquired resistance), continuation on current therapy is recommended. | 77.8% |

| For most asymptomatic men who were treated with abiraterone acetate + prednisone or enzalutamide for first-line mCRPC and who had initial response followed by radiologic + PSA progression (secondary acquired resistance), docetaxel is the preferred second-line treatment. | 100% |

| For most men who were treated with abiraterone acetate + prednisone or enzalutamide for first-line mCRPC and who had an initial response followed by progression, docetaxel is the preferred second-line treatment. | 96.3% |

| For most men with mCRPC who are progressing on or after docetaxel for mCRPC, abiraterone acetate + prednisone, or enzalutamide is the preferred second-line treatment for men without prior abiraterone acetate + prednisone or enzalutamide treatment. | 100% |

| In asymptomatic men with mCRPC and PSA-only progression on abiraterone acetate + prednisone, a steroid switch to dexamethasone is recommended. | 85.2% |

|

| |

| mCRPC | |

|

| |

| For most asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic men with mCRPC who did not receive docetaxel or abiraterone acetate + prednisone in the castrationsensitive setting, abiraterone acetate + prednisone or enzalutamide is the preferred first-line treatment for mCRPC. | 100% |

| Chemotherapy used after initial ARAT therapy is not felt to restore sensitivity to further ARAT use. | 74.1% |

| In the mCRPC setting, fatigue related to enzalutamide was treated with a dose reduction of enzalutamide. | 88.9% |

|

| |

| Genetic testing | |

|

| |

| In men with DNA repair defects (germline or somatic) who progress early on ADT to mCRPC, first-line mCRPC should be treated with standard options. | 78% |

| In men with newly diagnosed metastatic (M1) PCa, genetic counselling and testing is recommended in a minority of selected patients. | 74.1% |

| In men with newly diagnosed metastatic (M1) PCa, genetic counselling and testing is recommended for men with a positive family history for PCa/breast cancer/ovarian cancer.* | 88.9% |

| In men with newly diagnosed metastatic (M1) PCa, genetic counselling and testing is recommended for men with a positive family history for other cancer syndromes (e.g., hereditary breast cancer and ovarian cancer syndrome and/or pancreatic cancer, or Lynch syndrome).* | 74% |

|

| |

| Imaging | |

|

| |

| For most men with mCSPC, CT and bone scintigraphy is the recommended imaging modality. | 77.8% |

| For men with CSPC who have received local treatment with curative intent (± salvage radiation therapy), PET-CT (PSMA, choline or FACBC [fluciclovine]) imaging is the modality recommended to diagnose an oligometastatic recurrent state. | 74.1% |

Questions belonged to the same question but have been split out in the table for ease of review.

ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy; AR: androgen receptor; ARAT: androgen receptor targeted therapy CRPC: castration-resistant prostate cancer; CSPC: castration-sensitive prostate cancer; CT: computed tomography; LHRH: luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone; m: metastatic; MFS: metastasis-free survival; nm: non-metastatic; PCa: prostate cancer; PET: positron-emission tomography PSA: prostate-specific antigen; PSADT: prostate-specific antigen doubling time; PSMA: prostate-specific membrane antigen.

Of the supplementary questions that occurred via an online survey following Consensus Forum, threshold of consensus (>74%) was reached in 19/50 questions (Supplementary Appendix; available at cuaj.ca).

Reporting areas of consensus, simple majority, and variability

Areas of consensus and related discussion are reported below. Selected areas of simple majority vote (>50% agreement) and areas of variability are reported below and in the Supplementary Data section.

1. Biochemical recurrence following radical therapy

Consensus was reached for the following questions: when to begin androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) for biochemical recurrence following local definitive therapy, what type of ADT to use, and the frequency of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monitoring while on ADT for biochemical recurrence following definitive local therapy.

When to begin ADT

89% of physicians indicated that they primarily look at absolute PSA level (majority use >5 ng/mL post-radical prostatectomy or >10 ng/mL post-radical radiation therapy) to determine when to begin ADT for PSA recurrence following local radical therapy. Other factors that did not reach consensus were PSA doubling time (PSADT) <10 months (63% of physicians) and high-risk pathologic features (i.e., high Gleason score) (33% of physicians).

What method of ADT

93% of physicians recommend initiating intermittent ADT for PSA-only recurrence following local radical therapy rather than continuous ADT.

Frequency of PSA monitoring while on ADT for biochemical recurrence

93% of physicians indicated monitoring PSA every 3–4 months during ADT treatment for PSA recurrence. The panel commented that this frequency of testing reflects a need for timely assessment of PSADT in patients developing castration resistance.

2. nmCRPC

Consensus was reached for the PSADT threshold on which to begin treatment for nmCRPC, interpretation of PSADT in the context of imaging results, and use of a metastasis-free survival (MFS) endpoint to determine start of second-generation androgen receptor (AR) targeted therapy (ARAT).

PSADT threshold to begin treatment in nmCRPC

78% of physicians indicated using a PSADT threshold of <10 months to begin second-generation ARAT in nmCRPC. During the discussion, some participants discussed that the PSADT in the SPARTAN8 and PROSPER9 study populations was <6 months for the majority of study patients. However, participants also discussed that all patients with PSADT <10 months (both <6 months and >6 months) were observed to benefit from therapy.

Role of absolute PSA levels

Although there is evidence for elevated absolute PSA levels as a predictive marker of time to metastases and overall survival (OS),10,11 when the panel was asked to consider a patient with elevated PSA from 10–20 ng/mL and PSADT >10 months, the consensus (89%) was that they would still use PSADT <10 months as a trigger to begin treatment. In patients with absolute PSA of 20–40 ng/mL, 30% (n=8) of physicians considered initiating second-generation AR therapy, despite PSADT of >10 months.

PSADT in the context of imaging results

When PSADT <10 months and conventional imaging is negative for metastases, 96% of physicians indicated they would treat with agents approved for nmCRPC, such as apalutamide or enzalutamide. Since the consensus forum occurred prior to the availability of evidence for darolutamide, darolutamide could not be included in the consensus questions; however, the phase 3 data has since been published and a similar indication is anticipated from Health Canada. When PSADT <10 months, conventional imaging is negative for metastases, and positron-emission tomography (PET)-based imaging is positive for metastases, 89% of physicians indicated they would treat these patients with nmCRPC agents, such as apalutamide or enzalutamide. Regarding this latter scenario, the panel acknowledged that classifying patients as simply “non-metastatic” or “metastatic” is complicated in the context of advanced imaging modalities, and beyond the scope of the questions posed at the consensus forum. However, the panel concluded that, regardless of the classification, patients with no metastases on conventional imaging and a PSADT <10 months are indeed the patients studied in the SPARTAN8 and PROSPER9 studies and, thus, are the patients expected to derive the benefits reported in these studies. On balance, the panel concluded that the available evidence supports treatment of these patients with apalutamide or enzalutamide regardless of PET imaging.

MFS endpoint for treatment decision-making in nmCRPC

The use of the MFS endpoint was found to be sufficient for treatment decision-making in nmCRPC. Physicians were in full agreement (100% consensus) that surrogate endpoints likely correlated with OS, such as MFS, provide sufficient evidence for treatment decision-making in nmCRPC. During the discussion, it was highlighted that the positive voting results of this question reflected the large magnitude of MFS benefit reported by the SPARTAN8 and PROSPER9 studies.

3. mCSPC

Consensus was reached in the type of ADT used for high-volume mCSPC and the treatment of the primary in low-volume/low-risk patients and high-volume/high-risk patients.

Type of ADT used for high-volume mCSPC

81% of physicians use continuous luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist ± short-course first-generation anti-androgen in the majority of their patients; 11 % use LHRH antagonists and 7.4% use continuous complete androgen blockage (LHRH analog ± first-generation AR antagonists).

Treatment of primary

In de novo, low-volume, asymptomatic mCSPC, 74% of physicians indicated they would treat the primary in addition to systemic therapy, while 19% of physicians indicated they would consider treatment to the primary in select patients. In terms of the preferred type of treatment, 96% of physicians indicated that radiation therapy was preferred based on recent evidence from the STAMPEDE trial.12 In de novo, high-volume, asymptomatic mCSPC, 78% of physicians indicated they would not recommend treatment of primary in addition to systemic therapy, but during the discussion, the panel acknowledged that radiation is sometimes still given to patients in whom there are concerns about local symptoms and local progression, and may be on the borderline of the low-volume definition.

4. Sequencing of treatments

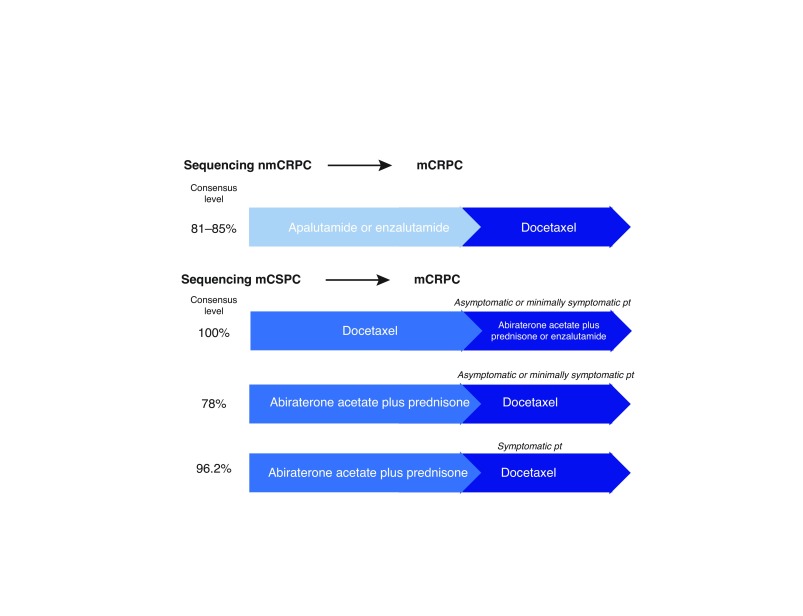

Consensus was reached across all treatment sequencing scenarios, including nmCRPC to mCRPC, mCSPC to mCRPC, and mCRPC first-line to second-line therapy.

nmCRPC to mCRPC

If apalatumide or enzalutamide was used for nmCRPC, >80% of physicians indicated they would sequence to docetatel.

mCSPC (docetaxel) to mCRPC

If docetaxel was used for mCSPC followed by asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic progression, 100% of physicians indicated they would sequence to abiraterone plus prednisone, or enzalutamide for mCRPC. If the patient was symptomatic, 70% of physicians indicated they would sequence to abiraterone plus prednisone or enzalutamide, 15% of physicians indicated they would use docetaxel for mCRPC, followed by approximately 7.5% who would use cabazitaxel and approximately 7.5% who would use radium-223. This scenario assumed that the patient had received and responded to six cycles of docetaxel and were now progressing symptomatically with no visceral metastases. A few panel members commented that the evidence for docetaxel re-challenge was limited and if the disease-free interval was short between completion of docetaxel and progression of symptoms, the patient would be unlikely to respond to docetaxel re-challenge.

mCSPC (abiraterone plus prednisone) to mCRPC

If abiraterone plus prednisone was used for mCSPC and the patient was asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, 78% of physicians indicated they would sequence to docetaxel, and 15% of physicians indicated they would sequence to enzalutamide for mCRPC. During the discussion, some physicians explained their preference for use of enzalutamide after abiraterone plus prednisone in this setting by citing the Chi crossover study13 and the opportunity to avoid or delay chemotherapy in the mCRPC population. If abiraterone plus prednisone was used for mCSPC and the patient was symptomatic, 96% of physicians indicated they would sequence to docetaxel for mCRPC.

mCRPC first-line (ARAT) to second-line

If the first-line treatment was abiraterone plus prednisone or enzalutamide and the patient was experiencing asymptomatic PSA progression, 78% of physicians indicated they would continue the current treatment course. However, if the patient was exhibiting asymptomatic radiographic + PSA progression, 100% of physicians indicated they would switch to docetaxel. If progression was symptomatic progression, 96% of physicians indicated they would switch to docetaxel for second-line treatment. Given the limited data for radium-223, the consensus forum did not consider scenarios where radium-223 was initiated for first-line mCRPC.

mCRPC first-line (docetaxel) to second-line

If the first-line treatment was docetaxel and there was no prior use of abiraterone plus prednisone or enzalutamide, 100% of physicians indicated they would use abiraterone plus prednisone or enzalutamide as second-line treatment.

Chemotherapy sandwiched between ARAT sequencing

The panel did not feel that chemotherapy used after initial ARAT therapy restores sensitivity to further ARAT use (74% of physicians). During the discussion, the panel noted that while some data exist that suggest a better response when chemotherapy is used between AR therapy, it is more likely that this is related to a break from AR therapy, which allows for re-proliferation of hormone-sensitive clones before re-exposure.13–16

Sequencing combinations for nmCRPC to mCRPC and mCSPC to mCRPC are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Various sequencing combinations. CRPC: castration-resistance prostate cancer; CSPC: castration-sensitive prostate cancer; m: metastatic; nm: nonmetastatic; pt: patient.

5. mCRPC

Consensus was reached for the selection of first-line treatment and steroid-switching for rising PSA among patients taking abiraterone plus prednisone.

First-line treatment CRPC

For men who were not previously treated with docetaxel or abiraterone plus prednisone in the mCSPC setting, the vote was unanimous — 100 % of physicians indicated they would use abiraterone plus prednisone or enzalutamide.

Steroid switch

85% of physicians indicated they would switch from prednisone to dexamethasone in patients treated with abiraterone plus prednisone for mCRPC who exhibited PSA progression alone. During the discussion, the panel also elaborated that referral to medical oncologist should be considered at the time of steroid switch and restaging should be ordered.

6. Oligometastatic prostate cancer

No questions reached the threshold level of consensus in this section. Greater than 50% of physicians agreed on a response for several questions but not at the level of consensus (Supplementary Appendix; available at cuaj.ca).

7. Access to treatments

No questions reached the threshold level of consensus.

8. Genetic testing in prostate cancer

In patients with DNA repair defects (germline or somatic) who progress early on ADT, 78% of physicians (consensus) indicated they would treat with standard first-line treatment for mCRPC.

Newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer

Panel consensus (74%) was reached that genetic counselling and testing should be conducted in select patients with newly diagnosed metastatic PCa. Further discussion of which select patients were most appropriate for genetic counselling and testing revealed that 89% of physicians would recommend testing for men with positive family history for prostate, breast, and ovarian cancer. Other circumstances for testing were patients with positive family history of other cancers (75%), men <60 years of age at diagnosis (67%), patients with visceral metastases (48%), and those with intraductal or cribriform pathology (44%).

Approximately one-quarter of physicians (26%) indicated they would recommend genetic counselling and testing in most patients.

9. Referrals

Consensus agreement was not reached on the referral-based questions.

10. Imaging

PET-computed tomography (CT) imaging to diagnose oligometastatic recurrence

Consensus was reached in the role of PET-CT imaging to diagnose oligometastatic-recurrent state in men with CSPC after local treatment with curative intent (± salvage radiation therapy), where 74% of physicians recommend PET-CT in this scenario and 26% recommend standard CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and bone scintigraphy.

CT and bone scintigraphy for mCSPC

Consensus was also reached in the use of CT and bone scintigraphy for most men with mCSPC, where 78% would use standard CT and bone scintigraphy and 22% would use next-generation imaging.

Discussion

Physicians treating advanced PCa face challenges in making treatment decisions in the face of a paucity of high-level evidence to guide practice. Consensus development methods may be useful in these types of situations by providing another mechanism to synthesize available evidence together with expert opinion and contextual patient factors to develop recommendations.

We applied a modified Delphi process to engage a multidisciplinary panel in several rounds of review and feedback to develop and refine a comprehensive survey of practice questions. This was followed by a consensus development day that enabled the panel to meet in-person to discuss and vote on each practice question and, ultimately, identify areas of consensus using a predefined threshold of 74% agreement. The panel identified 30 consensus areas in advanced PCa management.

Consensus aligned with existing high-quality evidence when available and reflected rapid uptake and synthesis of new evidence in emerging areas such as nmCRPC and mCSPC. In nmCRPC, physicians were in consensus agreement to treat their castration-resistant patients who were negative for metastases on conventional imaging with apalatumide or enzalutmide and ongoing ADT when PSADT dropped to <10 months, aligning to the recent data from the SPARTAN8 and PROSPER9 studies. In mCSPC, there was consensus agreement for treating the primary tumor with radiation therapy in patients with low-volume prostate cancer, which aligns with recent data from the STAMPEDE radiotherapy analysis.12

Consensus was also observed in situations where level 1 evidence does not exist. In particular, a high degree of consensus was seen in treatment-sequencing practices despite the limited data available to guide these types of treatment decisions.

Establishing consensus for a sequencing approach for treatments across the disease spectrum was a key output of the expert panel. After use of apalutamide or enzalutamide with ongoing ADT for nmCRPC, the consensus of the panel was to sequence to docetaxel upon progression to mCRPC. In mCSPC, if progression occurred following docetaxel treatment, the consensus was to sequence next to abiraterone acetate + prednisone, or enzalutamide for mCRPC. Similarly, if progression occurred while on abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, then the panel was in consensus to sequence to docetaxel therapy for mCRPC. Lastly, for mCRPC, if patients had not been previously treated with next generation AR therapy or docetaxel, the panel was unanimous that they would use abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or enzalutamide for first-line mCRPC, followed by docetaxel for second-line therapy. If docetaxel had been used in first-line mCRPC, they were in full consensus for using abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, or enzalutamide for second-line treatment.

Over the course of the consensus discussions, the panel identified several areas where additional research is critically needed to guide more informed treatment decisions. Oligometastatic disease, in particular, was felt to require substantially more research, starting with a unified definition of what represents clinically meaningful oligometastatic disease, the role of stereotactic body radiation therapy as metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic castration-resistant and castration-sensitive disease, treatment of newly diagnosed castration-sensitive oligometastatic disease, and oligometastatic-recurrent castration-sensitive disease.

The role of genetic testing was also flagged as an area for further research, especially how the presence of DNA repair defects could influence treatment, such as use of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and treatment decisions in mCRPC, and the role of genetic testing in newly diagnosed metastatic and localized PCa.

There are some limitations associated with this work. First, the evidence in this field is changing rapidly, and while this report provides a strong snapshot of current practice in Canada from a highly specialized, multidisciplinary panel, it is at risk of becoming outdated quickly as more evidence emerges. The consensus voting occurred in December 2018 and was based on the available data at the time. The evidence for newer agents, such as darolutamide, became available after the consensus forum. Second, the consensus panel was primarily composed of academic, hospital-based specialists; some specialty populations, such as radiation oncologists, were under-represented on the consensus panel, and future research is needed to understand the extent to which practice in the community setting is similar or different from the specialist panel. Third, because many of the recommendations are based on expert opinion, it is important to note that the information used to formulate the recommendations is of a lower level of evidence relative to randomized trials and other forms of interventional research.

Despite these limitations, we feel that the consensus recommendations arising from the consensus forum address several important gaps in the management of advanced PCa and will be of value to Canadian PCa physicians. The consensus development process was able to capture how leading Canadian PCa physicians have synthesized the best available data and incorporated other key knowledge of patient risk factors, treatment history, and drug characteristics in order to guide treatment decision-making in the absence of level 1 evidence. The consensus recommendations are also the product of a diverse scientific panel of multidisciplinary experts and represent important areas of Canadian consensus, and in some cases, lack of consensus across the country.

Conclusions

A Canadian consensus forum of PCa specialists identified areas of consensus in nearly 50% of questions discussed. The remaining questions showed a range of simple majority agreement or considerable variability in practice. These results reflect real-world practice. Areas of variability may represent opportunities for further research, education, and sharing of best practices. These findings reinforce the value of multidisciplinary consensus initiatives to optimize patient care.

Supplementary data from Canadian consensus forum on advanced prostate cancer management

Non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC)

Selected areas of > 50% panel agreement

When to switch therapy

37% of physicians indicated they would wait for radiographic progression before switching therapy to subsequent therapy following apalutamide or enzalutamide. No physicians felt prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-only progression was sufficient to switch therapy. Fifty-nine percent of physicians indicated they would wait for another type of progression in addition to radiographic progression.

Asymptomatic oligometastatic progression

70% of physicians indicated they would continue treatment and treat metastatic sites (i.e., stereotactic body radiotherapy) in patients who develop asymptomatic oligmetastatic disease while on apalutamide or enzalutamide, while 19% would switch treatment to another androgen receptor (AR) therapy, citing the switch to abiraterone plus prednisone in the SPARTAN study. During the discussion, the panel clarified that they interpreted progression in this question as the appearance of the first (SINGLE) oligometastatic site. While there was a reasonably high level of agreement on the preferred treatment approach in this question, this was highlighted as an area where further research is needed. Chemotherapy, while not the leading approach here, was noted to still play a role in select patients.

Role of PFS2 data

In terms of the interpretation of PFS2 data, 52% of physicians indicated that the PFS2 evidence is promising and would like to see overall survival (OS) results following final analysis of SPARTAN; 44% indicated that the data supports early treatment. Collectively, 96% of physicians felt that the PFS2 evidence is promising or supports that the magnitude of benefit seen with initiating treatment earlier in the nmCRPC state is greater than delaying treatment initiation to early metastatic (m)CRPC.

Treatment selection in the absence of contraindications

70% of physicians indicated having no preferred choice between apalutamide or enzalutamide in the absence of contraindications and assuming equivalent access to both therapies, while 26% preferred apalutamide and 4% preferred enzalutamide. During the discussion, one reason cited for preference for apalutamide was PSF2 results from SPARTAN and anecdotal experience of having to reduce the dose of enzalutamide for fatigue in an otherwise asymptomatic patient population. Reasons cited for preference of enzalutamide over apalutamide was familiarity with the agent and experience with its use.

Treatment selection in patients with comorbidities

The presence of patient comorbidities was not observed to definitively influence treatment selection between agents for nmCRPC (Supplementary Fig. 1). Overall, no clear preference between the agents was observed for patients with pre-existing hypertension, renal insufficiency, pre-existing arrhythmias, pre-existing cardiac ejection fracture <45%, and active liver disease. While not reaching threshold of consensus, greater than half of physicians indicated a preference for apalatumide with ongoing androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with pre-existing cognitive impairment or significant fatigue, and enzalutamide in patients with pre-existing hypothyroidism.

Managing side effects

There were variable comfort levels in managing side effects related to AR therapy, and differences in referral practices for management of adverse events (AEs) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Prostate cancer specialists appear to be comfortable managing osteoporosis or osteopenia, rash, and fatigue, but would prefer to refer to specialists for other AEs.

Metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC)

Selected areas of > 50% panel agreement

High volume/high-risk mCSPC

67% of physicians indicated they would add abiraterone acetate plus prednisone to ADT in this subgroup of mCSPC patients, while 33% of physicians indicated they would add docetaxel.

Low-volume/low-risk mCSPC

63% of physicians indicated they would add abiraterone actate plus prednisone to ADT, while 33% of physicians indicated they would just continue ADT alone. No physicians recommended the use of docetaxel in this patient population. During the discussion, the panel discussed the absolute magnitude of OS benefit (4.4%) reported from STAMPEDE for use of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in the low-volume mCSPC subset, noting that the magnitude of benefit was small but even small benefits of OS may be worth considering as a potential treatment option.17 The panel also debated the appropriate interpretation of the data, given that this subset analysis was a retrospective, post-hoc analysis of the STAMPEDE data.

Treatment selection

The presence of certain prognostic or patient features were observed to guide treatment selection to varying degrees. A preference for the use of abiraterone-prednisone was observed for young, healthy patients with low-volume disease (89% of physicians), Gleason >8 (78%), extensive bulky lymph nodes only (89%), and high-volume metastatic disease with poor performance (85%). A preference for the use of docetaxel was observed for young, healthy patients with high-volume disease (74% of physicians) and high-volume metastases with low PSA (78%) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC)

Selected areas of > 50% panel agreement

Dose reductions for treatment side effects

When using abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, 55% of physicians indicated they would attempt dose reduction of abiraterone acetate in most of their patients for side effects other than elevated liver function enzymes. For enzalutamide, 70% of physicians indicated they would attempt a dose reduction of enzalutamide in most of their patients. If the side effect was fatigue, 89% of physicians indicated they would attempt a dose reduction of enzalutamide. During the discussion, the panel felt it was important to further elaborate that in their anecdotal experience, the proportion of patients experiencing a significant AE that would require dose reduction or a change in management is generally lower with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone than with enzalutamide.

Treatment selection

Certain comorbidities were observed to influence treatment selection to varying degrees. A preference for abiraterone plus prednisone was observed among patients with a history of falls (74% of physicians), baseline fatigue (96%), and baseline neurocognitive impairment (83%). A preference for enzalutamide was observed among patients with diabetes (82%) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Oligometastatic prostate cancer

Selected areas of > 50% panel agreement

Definition of oligometastatic prostate cancer

70% of physicians defined this as a limited number of bone and/or lymph node metastases that can be treated with local therapy, and 26% of physicians defined it as a limited number of any metastases (including visceral). During the discussion, the panel noted this as an area where further study is needed.

Cutoff number of metastases for oligometastatic prostate cancer

59% of physicians felt the appropriate cutoff was <5 metastases, while 33% of physicians felt the appropriate cutoff was <3 metastases.

Selected areas of variability in patient management

Variability in physician voting was seen in the treatment approach for patients with oligometastatic CSPC and in the role of metastasis-directed therapy.

Variability in physician voting was seen in the treatment of newly diagnosed oligometastatic CSPC with an untreated primary tumor, where 48% of physicians would treat with ADT ± docetaxel or abiraterone acetate plus prednisone; 26% would give radical therapy to all lesions, including primary lesion, + ADT 24–36 months ±docetaxel (if high-volume) or abiraterone plus prednisone; and 26% would do the above, but give lifelong ADT. During the discussion, the panel expressed the need for clinical trials to study this scenario.

Variability in physician voting was also seen in the treatment of men with recurrent castration-sensitive oligometastatic prostate cancer after receiving local treatment with curative intent (± salvage radiation therapy), where 48% would treat with lifelong ADT ± docetaxel ± abiraterone acetate plus prednisone; 26% would add radical metastasis-directed therapy (surgery or radiation therapy) to the above; 15% would treat with metastasis-directed therapy with ADT 24–36 months; and 7% would treat with metastasis-directed therapy only.

If considering metastasis-directed therapy for men with recurrent castration-sensitive oligometastatic prostate cancer limited to pelvic lymph node metastases (detected by conventional imaging) in pelvis after local treatment with curative intent (± salvage radiation therapy), 30% of physicians would treat with ADT only; 26% would treat with whole pelvis radiotherapy ± boost to the suspicious nodes; 22% would give stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT); and 19% would do a salvage lymph node dissection.

Access to treatments

Public reimbursement for coverage of using a second AR agent in mCRPC

When physicians voted on whether provincial funding should be available for use of a second-generation AR agents in patients with mCRPC, 48% of physicians indicated that public provincial reimbursement should be provided for a second AR agent post-docetaxel (sandwich use), and 33% indicated yes, with no limitations irrespective of sandwich use. Collectively, this suggests that 81% of physicians see value in access to a second AR agent. During the discussion, the panel elaborated on the value of making funding available so that physicians can have the flexibility to apply their expertise to choose the best treatment course for the patient at this stage.

Public reimbursement for coverage of a second AR agent after use in mCSPC or nmCRPC

Fifty-two percent indicated yes, with no limitations, and 41% indicated yes, to be used with chemotherapy in between. Collectively, this suggests that 93% of physicians see value in access to a second AR agent.

Referrals

Selected areas of >50% panel agreement

Referral of patients with nmCRPC

67% of the panel felt that referral to the local physician (any specialty) who is most familiar with the management of these patients was appropriate; 26% felt that referral should be made to a regional cancer center for opinion/management by a multidisciplinary group.

Referral of patients with mCSPC

52% of the panel felt patients should be referred to a regional cancer center for opinion/management by a multidisciplinary group; 33% felt patients should be referred to a local physician (any specialty) who is most familiar with management of these patients. During the discussion, it was highlighted that the management of mCSPC is more complex than nmCRPC.

Referral of patients with mCRPC

41% of the panel felt patients should be referred to a regional cancer center for opinion/management by a multidisciplinary group, and 41% felt patients should be referred to a local physician (any specialty) who is most familiar with management of these patients.

Overall, these results demonstrate that >80% of the panel recommend referral of these patients to experienced clinicians or centers specialized in treating advanced prostate cancer.

Genetic testing and counselling

Selected areas of variability in patient management

Variability in practice was seen in the panel’s perspectives on the role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for the mCRPC treatment plan for low-risk, clinically localized prostate cancer in the presence of germline mutations, and newly diagnosed metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in the presence of DNA repair defects.

PARP inhibitor for mCRPC in the presence of DNA repair defects (germline or somatic)

44% of physicians would use a PARP inhibitor in most of their patients if available, and 30% were not sure. During the discussion, the panel highlighted that this is still an experimental treatment option in Canada and requires more research.

Low-risk clinically localized prostate cancer and germline BRCA1, BRCA2, or ATM mutation

63% of physicians indicated that the presence of germline BRCA1, BRCA2, or ATM mutation would make them less likely to offer surveillance, while 33% would not recommend active surveillance.

Newly diagnosed metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in the presence of DNA repair defects (germline or somatic)

59% of physicians indicated they would continue with standard treatment, while 37% would be more likely to recommend addition of docetaxel to ADT.

Imaging

Selected areas of >50% panel agreement

Frequency of imaging in mCPSC

65% of the panel indicated they would image at baseline and then at PSA nadir and progression (confirmed PSA rise or clinical progression).

Frequency of imaging in mCRPC

56% would image at baseline and then at PSA nadir and progression (confirmed PSA rise or clinical progression), and 30% would image at baseline then regular imaging every 3–6 months.

The voting results generally reflected that whether patients were mCSPC or mCRPC, most of the panel would image at baseline, nadir, then at progression, while a small proportion would image regularly every 3–6 months.

Treatment selection preferences in patients with comorbidities. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy.

Approach to management of treatment adverse effects.

Treatment selection in metastatic castrate-sensitive prostate cancer across clinical scenarios. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

Treatment selection preferences in patients with comorbidities.

Supplementary Table 1.

Canadian consensus forum members by specialty and region

| First name | Last name | Region | Specialty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fred | Saad | QC | Urologist |

| Kim | Chi | BC | Medical oncologist |

| Tony | Finelli | ON | Urologist |

| Sebastien | Hotte | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Christina | Canil | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Alan | So | BC | Urologist |

| Shawn | Malone | ON | Radiation oncologist |

| Bobby | Shayegan | ON | Urologist |

| Lorne | Aaron | QC | Urologist |

| Naveen | Basappa | AB | Medical oncologist |

| Henry | Conter | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Brita | Danielson | AB | Radiation oncologist |

| Geoffrey | Gotto | AB | Urologist |

| Robert | Hamilton | ON | Urologist |

| Jason | Izard | ON | Urologist |

| Anil | Kapoor | ON | Urologist |

| Michael | Kolinsky | AB | Medical oncologist |

| Aly-Khan | Lalani | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Jean-Baptiste | Lattouf | QC | Urologist |

| Chris | Morash | ON | Urologist |

| Scott | Morgan | ON | Radiation oncologist |

| Tamim | Niazi | QC | Radiation oncologist |

| Krista | Noonan | BC | Medical oncologist |

| Michael | Ong | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Ricardo | Rendon | NS | Urologist |

| Sandeep | Sehdev | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Jeffrey | Spodek | ON | Urologist |

Supplementary Table 2.

Consensus a cross the topic areas

| Topics | Questions | Consensus | No consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Biochemical recurrence following radical local definitive therapy | 4, 5, 6, (7 eliminated) | 3 | 0 |

| 2. Non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) | 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21 | 5 | 7 |

| 3. Metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) | 22, 22b, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 | 4 | 7 |

| 4. Sequencing of Systemic Treatment | 17, 18, 32, 34, 35, 36, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 | 10 | 1 |

| 5. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) | 33, 37, 43, 44, 45 | 3 | 2 |

| 6. Oligometastatic prostate cancer | 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 | 0 | 5 |

| 7. Funding of treatments | 51, 52 | 0 | 2 |

| 8. Referral for care | 60, 61, 62 | 0 | 3 |

| 9. Genetic testing in prostate cancer | 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Imaging in advanced prostate cancer | 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 | 2 | 3 |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Neil Fleshner, Dr. Frederic Pouliot, and Dr. Jeffrey Spodek for their contributions to the development of the consensus questions. They would also like to thank Delna Sorabji for her contributions to the design and execution of the project, as well as Timothy Doyle for his work providing editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Saad has served as a consultant for, and received funding from, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Janssen, and Sanofi. Dr. Canil has been an advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Eisai, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer; has received travel grants from Amgen and Sanofi; has received consulting honoraria from Janssen; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Janssen, and Roche. Dr. Finelli has been an advisory board member for Abbvie, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, Ipsen, Sanofi, and TerSera; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, Bayer, and Janssen. Dr. Hotte has received institutional research funding or consulting honoraria from Astellas, Bayer, and Janssen. Dr. Malone has served on advisory boards and/or received honoraria from Abbvie, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, Sanofi, and TerSera; and has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Shayegan has received grants or honoraria from Abbvie, Astellas, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Astellas and Janssen. Dr. So has received honoraria from and served on advisory boards for Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, Ferring, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Astellas and Janssen. Dr. Aaron has attended advisory boards for Abbvie and Janssen; has been a speaker for Ferring and Janssen; holds investments in Johnson & Johnson; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, Ferring, and Janssen. Dr. Basappa has served on advisory boards for and received honoraria and/or grants from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, and Roche. Dr. Conter has received grants and/or honoraria from Astellas, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Novartis; and has participated in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and Takeda. Dr. Danielson has received advisory board honoraria and speaker fees from Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, and Janssen. Dr. Gotto has received honoraria and served on advisory boards for Amgen, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Merck, Roche, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Amgen, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Janssen, and Myovant. Dr. Hamilton has served on advisory boards for and/or received honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, and TerSera; and has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Izard has been an advisory board member or consultant for Abbvie, Astellas, Ferring, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, AstraZeneca, and Merck. Dr. Kapoor has attended advisory boards for and participated in clinical trials supported by Amgen, Astellas, Janssen, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Dr. Kolinsky has been a consultant for Janssen; has received honoraria and travel reimbursement from Astellas, AstraZeneca, BMS, Ipsen, Janssen, Merck, and Novartis; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, AstraZeneca, BMS, GSK, Ipsen, Janssen, Merck, and Roche. Dr. Lalani has received honoraria for ad hoc consultation or advisory board meetings from BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and TerSera; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Merck. Dr. Lattouf has attended advisory boards Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, Novartis, and Pfizer; and has received an educational grant from Janssen. Dr. Morash has attended advisory boards for Abbvie, Astellas, Ferring, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Abbvie (CRONOS II). Dr. Morgan has attended advisory boards for and received honoraria from Astellas, Bayer, and Janssen; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Janssen. Dr. Niazi has received research grants and honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas, Ferring, Janssen, and Sanofi. Dr. Noonan has been an advisory board member for Astellas, BMS, Janssen, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas. Dr. Ong has received honoraria from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, EMD Serono, Janssen, and Merck; and received a research grant from AstraZeneca and a GUMOC grant from Astellas. Dr. Rendon has attended advisory boards and has been a speaker for Amgen, Astellas, Ferring, and Janssen. Dr. Shayegan has received grants/honoraria from Abbvie, Astellas, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Astellas and Janssen. Dr. Sehdev has participated in advisory boards for Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Janssen. Mr. Hew and Ms. Park-Wyllie are employed by Janssen Canada. Dr. Chi has served on advisory boards and received honoraria and/or grant funding from Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, Roche, and Sanofi.

The consensus forum was supported by Janssen Canada.

References

- 1.Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2018;124:2785–800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillessen S, Attard G, Beer TM, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: The report of the advanced prostate cancer consensus conference APCCC 2017. Eur Urol. 2018;73:178–211. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgans AK, van Bommel AC, Stowell C, et al. Development of a standardized set of patient-centered outcomes for advanced prostate cancer: An international effort for a unified approach. Eur Urol. 2015;68:891–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:401–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Donovan A, Mohile SG, Leech M. Expert consensus panel guidelines on geriatric assessment in oncology. Eur J Cancer Care. 2015;24:574–89. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kea B, Sun BC. Consensus development for healthcare professionals. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10:373–83. doi: 10.1007/s11739-014-1156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. New Engl J Med. 2018;378:1408–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussain M, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Enzalutamide in men with nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. New Engl J Med. 2018;378:2465–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MR, Cook R, Lee KA, et al. Disease and host characteristics as predictors of time to first bone metastasis and death in men with progressive castration-resistant non-metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:2077–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreira DM, Howard LE, Sourbeer KN, et al. Predictors of time to metastasis in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urology. 2016;96:171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, et al. Radiotherapy to the primary tumor for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): A randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2353–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32486-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalef D, Annala M, Finch DL, et al. Phase 2 randomized cross-over trial of abiraterone + prednisone (ABI+P) vs. enzalutamide (ENZ) for patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCPRC): Results for 2nd-line therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(Suppl15):S5015. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.5015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyake H, Hara T, Ozono S, et al. Impact of prior use of an androgen receptor-axis-targeted (ARAT) agent with or without subsequent taxane therapy on the efficacy of another ARAT agent in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Canc. 2017;15:e217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maughan BL, Boudadi K, Nadal RM, et al. Intercalating docetaxel between novel hormone therapies (NHT) abiraterone and enzalutamide in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Does it resensitize patients to the second NHT agent? J Clin Oncol. 2017;34(Suppl15):e16550. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.e16550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MR, Saad F, Rathkopf DE, et al. Clinical outcomes from androgen signaling-directed therapy after treatment with abiraterone acetate and prednisone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Post-hoc analysis of COU-AA-302. Eur Urol. 2017;72:10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyle AP, Ali SA, James ND, et al. LBA4 effects of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone/prednisolone in high- and low-risk metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl8):722. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy424.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Treatment selection preferences in patients with comorbidities. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy.

Approach to management of treatment adverse effects.

Treatment selection in metastatic castrate-sensitive prostate cancer across clinical scenarios. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

Treatment selection preferences in patients with comorbidities.

Supplementary Table 1.

Canadian consensus forum members by specialty and region

| First name | Last name | Region | Specialty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fred | Saad | QC | Urologist |

| Kim | Chi | BC | Medical oncologist |

| Tony | Finelli | ON | Urologist |

| Sebastien | Hotte | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Christina | Canil | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Alan | So | BC | Urologist |

| Shawn | Malone | ON | Radiation oncologist |

| Bobby | Shayegan | ON | Urologist |

| Lorne | Aaron | QC | Urologist |

| Naveen | Basappa | AB | Medical oncologist |

| Henry | Conter | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Brita | Danielson | AB | Radiation oncologist |

| Geoffrey | Gotto | AB | Urologist |

| Robert | Hamilton | ON | Urologist |

| Jason | Izard | ON | Urologist |

| Anil | Kapoor | ON | Urologist |

| Michael | Kolinsky | AB | Medical oncologist |

| Aly-Khan | Lalani | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Jean-Baptiste | Lattouf | QC | Urologist |

| Chris | Morash | ON | Urologist |

| Scott | Morgan | ON | Radiation oncologist |

| Tamim | Niazi | QC | Radiation oncologist |

| Krista | Noonan | BC | Medical oncologist |

| Michael | Ong | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Ricardo | Rendon | NS | Urologist |

| Sandeep | Sehdev | ON | Medical oncologist |

| Jeffrey | Spodek | ON | Urologist |

Supplementary Table 2.

Consensus a cross the topic areas

| Topics | Questions | Consensus | No consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Biochemical recurrence following radical local definitive therapy | 4, 5, 6, (7 eliminated) | 3 | 0 |

| 2. Non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) | 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21 | 5 | 7 |

| 3. Metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) | 22, 22b, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 | 4 | 7 |

| 4. Sequencing of Systemic Treatment | 17, 18, 32, 34, 35, 36, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 | 10 | 1 |

| 5. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) | 33, 37, 43, 44, 45 | 3 | 2 |

| 6. Oligometastatic prostate cancer | 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 | 0 | 5 |

| 7. Funding of treatments | 51, 52 | 0 | 2 |

| 8. Referral for care | 60, 61, 62 | 0 | 3 |

| 9. Genetic testing in prostate cancer | 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Imaging in advanced prostate cancer | 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 | 2 | 3 |