Abstract

Introduction

Increasing female matriculation into medical school has shown an increase in women training in academic urology, but gender disparity still exists within this male-dominated field. This study aims to evaluate publication productivity and rank differences of Canadian female and male academic urologists.

Methods

The Canadian Residency Matching Service (CaRMS) was used to compile a list of 12 Canadian accredited urology programs. Using each institution’s website, faculty members’ names, genders, academic positions, and leadership ranks were noted. SCOPUS© was consulted to tabulate the number of documents published, citations, and h-index of each faculty member. To account for temporal bias associated with the h-index, the m-quotient was also computed.

Results

There was a significantly higher number of men (164, 88.17%) among academic faculty than women (22, 11.83%). As academic rank increased, the proportion of female urologists decreased. Overall, male urologists had higher academic ranks, h-index values, number of publications, and citations (p=0.038, p=0.0038, p=0.0011, and p=0.014, respectively). There was an insignificant difference between men and women with respect to their m-quotient medians (p=0.25).

Conclusions

There is an increasing number of women completing residency in urology, although there are disproportionally fewer female urologists at senior academic positions. Significant differences were found in the h-index, publication count, and citation number between male and female urologists. When using the m-quotient to adjust for temporal bias, no significant differences were found between the gender in terms of academic output.

Introduction

The proportion of female students admitted to medical schools has significantly risen over the years. As such, entering medical school classes are at least 50% female.1 Along with this rise in female medical students, there has been a corresponding increase in women choosing the field of urology. However, despite of the dramatic increase in women pursuing urology, they only represent 33% of students matching into this specialty.2 According to data gathered by the American Urological Association, females represent 8.5% of total practicing urologists, although this number is expected to rise to 28% by 2050.3 While there is movement towards equality in urology, there are still shortcomings in the gender equalization of staff positions and academic rank. Despite female urologists working more and publishing at a greater rate than their male counterparts, there are fewer women obtaining senior leadership positions among academic physicians.4–6 A U.S. study by Meyer et al found that only 1.3% of female urologists occupy chair positions compared to 7.5% of males. Similarly, 11% of female urologists compared to 26% of male urologists held professorship positions at academic centers.7,8

This paper investigates the gender differences in the relationship between academic productivity and career advancement for Canadian male and female urologists.

Methods

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional study discerning gender and academic rank among university-affiliated urologists in Canada. Informed consent or institutional review board approval was not requested, as all data are publicly available. The data collected was assembled from January 2017 to June 2019 via a method already validated through several recent publications.9–19 A database was generated by consulting the Canadian Residency Matching Service (CaRMS), through which a total of 13 accredited urology programs were eligible for investigation. Of the 13 aforementioned programs, 12 institutions had the required faculty listings on their website or provided a list of their faculty members through email (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gender breakdown among urologists across Canadian institutions

| Institution | Total faculty | Male faculty | Female faculty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dalhousie University | 12 | 9 | 3 |

| University of Ottawa | 15 | 15 | 0 |

| Queen’s University | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| University of Toronto | 28 | 27 | 1 |

| McMaster University | 14 | 14 | 0 |

| Western University | 12 | 12 | 0 |

| University of Manitoba | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| University of Alberta | 8 | 7 | 1 |

| University of British Columbia | 27 | 24 | 3 |

| McGill University | 18 | 17 | 1 |

| Université de Sherbrooke | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Université Laval | 28 | 18 | 10 |

| Total | 186 | 164 | 22 |

Faculty members from the 12 programs were subsequently entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Only physicians holding an MD and/or MD/PhD degree with an appointment within the division of urology, having completed a urology residency program in an accredited institution were included. Along with the faculty’s name and gender, several other academic positions and leadership ranks were also noted. Gender identification was limited by name, faculty photo, or provincial college registration. SCOPUS© was consulted to gather information pertaining to the research productivity of each of the faculty members. Parameters recorded included number of documents published, citations, year of first publication, year of most recent publication, years since first publication, years since most recent publication, and Hirsch (h)-index. The h-index is a frequently used biometric that measures research productivity. Its computation uses both an author’s quantity of publications, as well as the number of citations. As such, it is both a qualitative and quantitative measure of an individual’s research performance and has been correlated with academic rank.20 A limitation of this index is its inherent advantage for more senior researchers. Individuals conducting investigations for a longer duration would have had more opportunity to publish and, thus, more opportunity to be cited. To account for the temporal bias associated with the h-index, the m-quotient was computed for each faculty member. This biometric tool takes into consideration the duration of the researcher’s publication career and is, therefore, a more accurate depiction of a faculty member’s research performance.21

Results

A total of 207 urologists, 179 men and 28 women, from 12 academic institutions across Canada were identified using faculty websites. Among these, academic rank and other variables were found and included for 186 staff members, 22 (11.83%) women and 164 (88.17%) men, which were included in the study (Table 2). For each of the academic ranks, the majority were males — 82.05% of assistant professors, 91.84% of associate professors, and 93.22% of full professors. In fact, as the academic ranking increased, there was a decrease in the number of female faculty. Assistant professors included 14 women while associate and full professor positions were held by four women each (Table 2). There was a significant difference in academic rank between the two genders (p=0.038).

Table 2.

Academic research activity and career duration for urology faculty by gender across Canada

| Position & gender | n (%) | Publications, median (range) | h-index, median (range) | Citations, median (range) | m-quotient, median (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full professor | 59 | ||||

| Male | 55 (93.22%) | 140 (13–578) | 31 (5–91) | 3148 (87–26671) | 1.05 (0.14–2.84) |

| Female | 4 (6.78%) | 69 (14–279) | 19 (8–57) | 1267.5 (384–10681) | 0.77 (0.32–1.90) |

| Associate professor | 49 | ||||

| Male | 45 (91.84%) | 59 (2–287) | 17 (1–45) | 890 (3–6355) | 0.86 (0.051–2.05) |

| Female | 4 (8.16%) | 25.5 (16–55) | 10.5 (8–23) | 450 (233–656) | 0.72 (0.35–0.96) |

| Assistant professor | 78 | ||||

| Male | 64 (82.05%) | 22.5 (1–183) | 8.5 (1–45) | 300.5 (1–6267) | 0.61 (0.053–3.75) |

| Female | 14 (17.95%) | 9.5 (2–54) | 4.5 (1–15) | 68.5 (3545) | 0.62 (0.26–150) |

| Total | 186 | ||||

| Male | 164 (88.17%) | 54.5 (1–578) | 16 (1–91) | 796 (1–26671) | 0.82 (0.05–13.75) |

| Female | 22 (11.83%) | 15 (2–279) | 8 (1–57) | 188.5 (3–10681) | 0.72 (0.26–1.90) |

The median publication count and range of publications was also assessed for the cohort of 186 urologists. For both males and females, the highest publication counts were observed in those with full professorship positions, wherein males had 140 (range 13–578) and females had a median of 69 (range 14–279) publications. The lowest median of publications was seen in the assistant professor category, in which men had a median of 22.5 (range 1–183) and women had a median of 9.5 (range 2–54) publications (Table 2). There was a significant difference (p=0.0011) between men and women for median and range of publications. In the associate professor category, men had a median publication count of 59 (range 2–287) whereas women had a median publication count of 25.5 (range 16–55). As such, men had higher numbers of publications in all professorship categories.

Citations followed a similar pattern to publication production. Citations were highest among full professors, with men having a median of 3148 (range 87–26671) and women having 1267.5 (range 384–10681) citations. The lowest citation values were seen among assistant professors, with men having a median of 300.5 (range 1–6267) and women having a median of 68.5 (range 3–545) citations (Table 2). There was a significant difference (p=0.014) between men and women with respect to citation median. Both publications and citations correlated with academic rank, a relationship that was observed for male and female urologists, although men had a higher median of citations in every professor rank (Table 2).

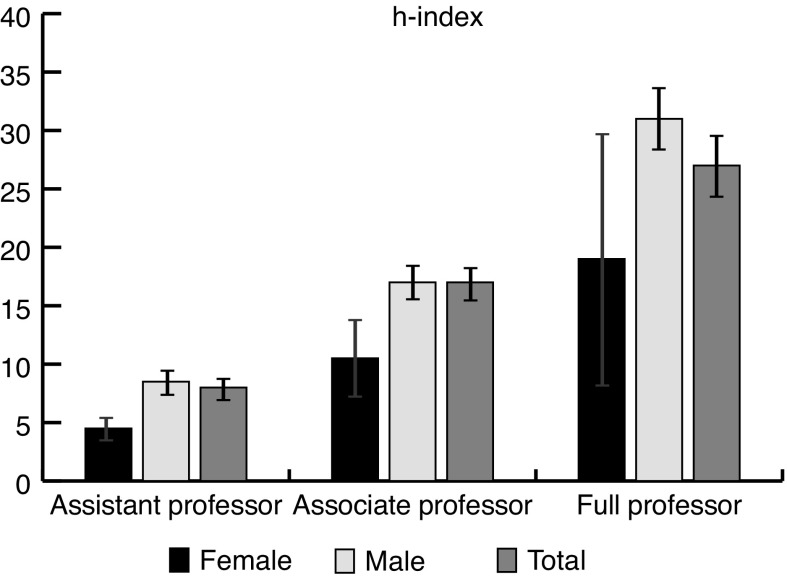

The h-index, incorporating both publications and citations, was used as a metric to assess the qualitative and quantitative research productivity of faculty members. The highest indices were seen among full professors, with men having a median of 31 (range 5–91) and women 19 (range 8–57). The lowest indices were observed among the assistant professors, with men having a median of 8.5 (range 1–45) and females 4.5 (range 1–15) (Table 2). There was a significant difference in the h-index between the two genders (p=0.0038). As seen in Fig. 1, both men and women follow a similar trajectory in terms of their h-indices — as academic rank increases, so does that h-index. Similarly, men had statistically higher h-indices in the assistant and associate professor rankings, but not in the full professor ranking due to the large error bars for women (Fig. 1). Comparable to publications and citations, the associate professor rank saw males with a higher h-index than their female counterparts. In this category, men had a median of 17 (range 1–45) compared to 10.5 (range 8–23) for women (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

h-indices for male and female urologists. For both genders, as academic rank increases, so does the h-index.

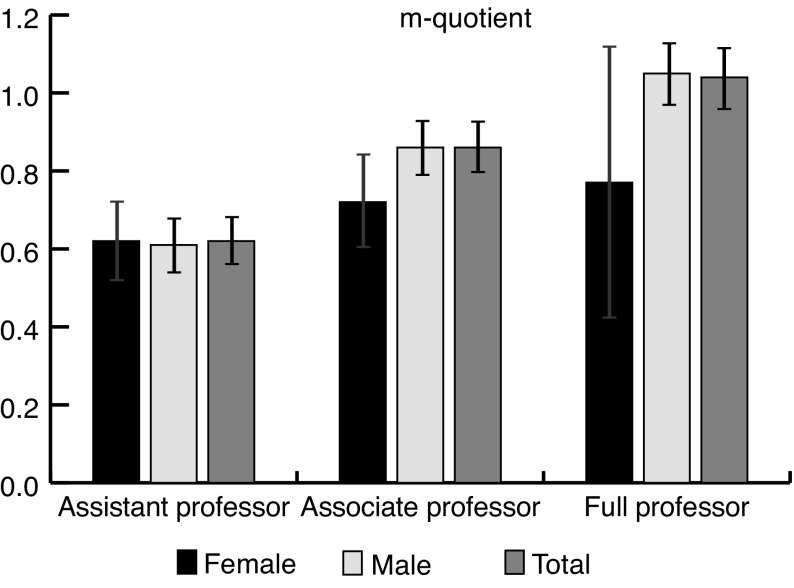

The m-quotient reflects the h-index while accounting for an individual’s academic career length. Although the h-index is a universal marker of research productivity, it is associated with temporal bias, as physicians with longer careers are more likely to have an increased number of publications and, consequently, citations. By including a physician’s career duration as part of the computation of the index, the m-quotient normalizes the variability in career durations and standardizes research productivity. For both men and women, the m-quotient increased with academic rank (Fig. 2). The large errors bars observed for women at full professor positions is due to the small sample (n=4) of women in this category and the large variability of values. Men employed as full professors had an m-quotient median of 1.05 (range 0.14–2.84) and women employed as full professors had an m-quotient median of 0.77 (range 0.32–1.90) (Table 2). In the associate professor rank, men had an m-quotient median value of 0.86 (range 0.051–2.05) and women had a median value of 0.72 (range 0.35–0.96). Interestingly, in the assistant professor category with the largest number of women, men had a median m-quotient of 0.61 (range 0.053–3.75) and women had a slightly higher median m-quotient of 0.62 (0.26–1.50) There was an insignificant difference between men and women with respect to their m-quotient medians (p=0.25).

Fig. 2.

m-quotients for male and female urologists. Again, for both genders, the m-quotient increases with academic rank.

Discussion

Women have been historically underrepresented in academic medicine. This was due to the lack of female matriculation into medical school, a tendency that has been improved over the years. Starting in 1969, the proportion of women enrolling in medical school began to significantly increase.21 This increase in matriculation saw a female medical school enrolment rate of 31% in 1981 augment to 47% in 2010.22 Surgical specialties began to see a similar increase in the proportion of females applying for residency positions. Among these, urology, a specialty dominated by men, has seen a substantially increasing pool of female applicants for residency positions, although women still remain a significant minority of the workforce.23 The proportion of female urologists in the U.S. has risen from 1.2% in 1995 to 8% in 2011, and is predicted to rise to 28% by 2050.7,24,25

The statistics in Canada follow a similar trend. Urology in Canada has become much more gender-neutral over the years. Starting from the 1970s, which saw the graduation of the first woman from a Canadian urology residency, there has been a steady increase in the enrolment of women in medical schools.26,27 With the increased admittance of female students, CaRMS has seen a greater proportion of female applicants for urology as a first-choice specialty. In 1998–1999, the proportion of females applying to urology was 19%; this increased to 27% in 2012–2015, which lead women making up one-quarter of the Canadian urology resident population. There was a similar trend in the proportion of female applicants to other surgical programs; 1998–1999 had a surgical cohort compromising of 25% women, whereas the proportion of women in surgical programs rose to 40% by 2012–2015.28

Career advancement is one metric that can be used to assess success in an academic center. Our study demonstrated that the absolute number of women decreases with advancing academic rank. Female urologists comprised 17.95% of assistant professors and only 8.16% and 6.78% of associate and full professors, respectively. Statistical analysis showed that academic rank differences between male and female urologists were significant (p=0.038). These data are similar to those found in the U.S., where men are more likely to occupy more senior positions and only 12% of female urologists see advancement past associate professorship compared to 33% of male urologists.7

Academic output of the urologists was measured by the median number of publications and was found to have been significantly different between men and women (p=0.0011), with male urologists having a median of 54.5 publications compared to 15 for female urologists. A study conducted by Yang et al in the U.S. found that women in urology have fewer publications than men in urology, although they are equally as likely to pursue fellowship training and choose an academic career.29 Given the results our study, it seems that Canadian female urologists follow a similar trend in reduced academic output.

To further evaluate research productivity, the h-index was computed for both genders in each cohort of professors. There was a significant difference between men and women (p=0.0038), similar to a finding in the U.S., where the median h-index of all male urologists was 11.67 compared to 6.33 for female urologists.7

In order to reduce the temporal bias associated with the h-index, the m-quotient was computed. Since a longer career duration was anticipated for males, thus resulting in a larger research output, the m-quotient’s ability to negate temporal bias was crucial. Interestingly, the m-quotient demonstrated an insignificant difference (p=0.25) between male (0.82) and female (0.72) urologists. This may indicate that the perceived superior academic output of male urologists, as demonstrated by their publication count and h-index, may simply be the result of a temporal bias due to longer careers. Because women have only started entering urology in larger quantities more recently, their academic output may be reduced. However, when adjusting for their relatively fewer years in practice, the m-quotient indicates that they are just as academically productive as their male counterparts.

There are several notions that may explain why females are often underrepresented in the upper echelons of academic medicine, most of which deal with a relative lack of research productivity, which can begin as early as residency training. Men have been shown to publish more during residency, which thereby increases their research career duration, allowing them to begin developing their h-index sooner.29 Not only do women tend to publish less during residency, but they also may prioritize family responsibilities over academic goals.20 Taking time for maternity leave, as well as child-rearing duties substantially diminish the time attributed to academic pursuits, such as publications and career advancement.20,30

The precedent for contemplating a perceived gender gap in academic productivity may be alternatively related to recruitment, career length, and practice settings. The lag effect of under-recruitment of women into urology is one major contributor to the issue. Before the increase of female matriculations in medical school, medicine, and by extension urology, was a male-dominated career. As female urologists began to enter the workforce, the faculties that recruited them had already had many other male urologists with long career durations. With longer career duration resulting in better measures of academic productivity, male urologists were more likely to see career advancement compared to the female urologists with relatively shorter career lengths.16 Women are also more likely to enrol in the clinician-educator rather than tenure track, and are hence more likely to prioritize teaching over academic research. This further reinforces lag effect in academic promotion of female urologists.25

Another issue faced by many female urologists is finding a mentor, a major setback compared to men. Mentors are crucial in exposing a student to a particular career and in providing them with research opportunities. Many urology residents cite excellent mentorship as one of the top reasons to pursue urology.31 It has been noted that female medical students report facing difficulties in finding a mentor in surgical fields, whether of the same gender or not. This is often compounded by the male-dominant nature of urology, and thus disadvantages women interested in pursuing urology relative to their male counterparts, who are able to find a mentor more readily. Without a mentor or a mentor in leadership positions, women would not be exposed to senior-level leadership and would not be as prepared for senior positions as male urologists.31–35 This may also explain why women in medicine are often less inclined to view leadership roles as desirable, and even when these leadership roles are attained, women feel less self-efficacious than men.36

There are several limitations in this study. There was an inherent degree of potential inaccuracy in obtaining faculty listing from institutional websites, as these may not be updated in real time. Moreover, the absence of a urologist on SCOPUS© was often associated with a lack of research production from said urologist. However, this may not necessarily be true. Moreover, name changes after divorce, marriage, or a change in institution can result in the unintentional incredibility of work. Furthermore, the faculty listing from l’Université de Montréal could not be obtained. Although the institution was contacted in an attempt to extract faculty data, the university refused to provide their urology staff listing. Lastly, there is some innate bias in the h-index that highlights its limitations. The h-index does not offer any differentiation between the publication of numerous papers of poor quality vs. a few papers of superior quality, and it does not discriminate between self-citations.37

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that gender disparity can be found within urology faculties across Canada. There is a significant difference between men and women in academic rank (p=0.038), with the proportion of women decreasing as academic rank increases. This may be the result of a plethora of factors, namely men having longer research-oriented careers, the lag effect of under-recruitment of women in urology, and the difficulty female urologists have in finding a mentor. Similarly, the results demonstrate a significant difference in the median of publications and citations (p=0.0011 and p=0.014, respectively), with men having considerably larger values in these categories. The h-index, a representation of research productivity, was significantly higher in men (p=0.0038), while the m-quotient, an indicator of research output accounting for temporal bias, did not show a significant difference between male and female urologists (p=0.25). With the continued increase of women pursuing urology, understanding and analyzing gender differences within the specialty is imperative. Namely, identifying and reducing the barriers that women face in achieving academic success is an instrumental consideration in order to achieve an optimally functioning work environment.

Footnotes

See related editorial on page 79

Competing interests: Dr. Khosa is the recipient of the Canadian Association of Radiologists – Young Investigator Award (2019) and the Vancouver Coastal Health – Healthcare Hero Award (2018). The remaining authors report no competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

This paper has been peer-reviewed

References

- 1.Leslie K, Harriet WH, Patricia H, et al. Women, minorities, and leadership in anesthesiology: Take the pledge. Anesth Analges. 2017;124:1394–6. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spencer ES, Allison MD, Nicholas RP, et al. Gender differences in compensation, job satisfaction, and other practice patterns in urology. J Urol. 2016;195:450–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SJ, Hyun G. Women in urology: Time to lean in. J Urol. 2014;191:e145. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed DA, Enders F, Lindor R, et al. Gender differences in academic productivity and leadership appointments of physicians throughout academic careers. Acad Med. 2011;86:43–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff9ff2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nonnemaker L. Women physicians in academic medicine-new insights from cohort studies. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:399–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss DA, Kovshilovskaya B, Breyer BN. Gender trends of urology manuscript authors in the United States: A 35-year progression. J Urol. 2012;187:253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer EN, Sara ML, Heidi AH, et al. Gender differences in publication productivity among academic urologists in the United States. Urology. 2017;103:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of American Medical Colleges. Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2015. 2015. [Accessed Sept. 30, 2018]. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/458712/1-3-chart.html.

- 9.Sheikh MH, Chaudhary AM, Khan AS, et al. Influences for gender disparity in academic psychiatry in the United States. Cureus. 2018;10:e2514. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamidizadeh R, Jalal S, Pindiprolu B, et al. Influences for gender disparity in the radiology societies in North America. Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211:831–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.19741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaikh AT, Farhan SA, Siddiqi R, et al. Disparity in leadership in neurosurgical societies: A global breakdown. World Neurosurg. 2018:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan MS, Usman MS, Siddiqi TJ, et al. Women in leadership positions in academic cardiology: A study of program directors and division chiefs. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28:225–32. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang HY, Rhee G, Xuan L, et al. Analysis of H-index in assessing gender differences in academic rank and leadership in physical medicine and rehabilitation in the United States and Canada. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98:479–83. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moghimi S, Khurshid K, Jalal S, et al. Gender differences in leadership positions among academic nuclear medicine specialists in Canada and the United States. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212:146–50. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Battaglia F, Shah S, Jalal S, et al. Gender disparity in academic emergency radiology. Emerg Radiol. 2019;26:21–8. doi: 10.1007/s10140-018-1642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah A, Jalal S, Khosa F. Influences for gender disparity in dermatology in North America. Int J Derm. 2018;57:171–6. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battaglia F, Jalal S, Khosa F. Academic general surgery: Influences for gender disparity in North America. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:e126. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.08.340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi M, Khurshid K, Sanelli PC, et al. Influences for gender disparity in academic neuroradiology. Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:18–23. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khurshid K, Shah S, Ahmadi M, et al. Gender differences in the publication rate among breast imaging radiologists in the United States and Canada. Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210:2–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svider PF, Pashkova AA, Choudhry Z, et al. Comparison of scholarly impact among surgical specialties: An examination of 2429 academic surgeons. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:884–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.23951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bornmann L, Daniel HD. The state of H-index research: Is the H-index the ideal way to measure research performance? EMBO Rep. 2009;10:2–6. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association of American Medical Colleges. US medical school applicants and students 1982–1983 to 2011–2012. [Accessed October 28, 2019]. Available at: https://www.exercise-science-guide.com/wp-content/uploads/U.S.-Medical-School-Applicants-and-Students-1982-83-to-2011-2012.pdf.

- 23.Halpern JA, Lee UJ, Wolff EM, et al. Women in urology residency, 1978–2013: A critical look at gender representation in our specialty. Urology. 2016;92:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.12.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradbury CL, King DK, Middleton RG. Female urologists: a growing population. J Urol. 1997;157:1854–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64884-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer AP, Blair JE, Ko MG, et al. Gender distribution of US medical school faculty by academic track type. Acad Med. 2014;89:312–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill C. On becoming the first woman urologist in Canada. CMAJ. 1980;122:356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian Resident Matching Service. CaRMS: R-1 match reports. [Accessed Jan. 7, 2019]. [updated 2015]. Available at: http://www.carms.ca/en/data-and-reports/r-1/

- 28.Anderson K, Tennankore K, Cox A. Trends in the training of female urology residents in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J. 2018;12:E105–11. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang G, Villalta JD, Weiss DA, et al. Gender differences in academic productivity and academic career choice among urology residents. J Urol. 2012;188:1286–90. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pagel PS, Hudetz JA. H-index is a sensitive indicator of academic activity in highly productive anaesthesiologists: Results of a bibliometric analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:1085–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerfoot BP, Nabha KS, Masser BA, et al. What makes a medical student avoid or enter a career in urology? Results of an international survey. J Urol. 2005;174:1953–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000177462.61257.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutikov A, Bonslaver J, Casey JT, et al. The gatekeeper disparity-why do some medical schools send more medical students into urology? J Urol. 2011;185:647–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGinty KL, Martin CA, DeMoss KL, et al. Future career choices of women psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 1997;18:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF03341527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bright CM, Duefield CA, Stone VE. Perceived barriers and biases in the medical education experience by gender and race. J Natl Med Assoc. 1998;90:681–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abu-Zaid A, Altinawi B. Perceived barriers to physician-scientist careers among female undergraduate medical students at the College of Medicine-Alfaisal University: A Saudi Arabian perspective. Med Teach. 2014;36:S3–7. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.886006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pololi LH, Civian JT, Brennan RT, et al. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: Gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:201–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreiner G. The slavery of the H-index — measuring the unmeasurable. Frontiers Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:556. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]