Presentation

Despite an ever-expanding spectrum of available tests, fever of unknown origin remains a diagnostic dilemma. A 40-year-old Nepalese man living in Rhode Island presented with a 1-week history of nausea, vomiting, fevers, and frontal headache. He denied neck stiffness, abdominal pain, diarrhea, rash, or urinary symptoms. In the emergency department, he had a temperature of 100.4° F (38.0° C) and was tachycardic to 108 beats per minute. His physical examination was otherwise normal.

Lumbar puncture demonstrated no pleocytosis. Polymerase chain reaction testing of cerebrospinal fluid was negative for herpes simplex virus and enterovirus; a western blot was negative for Lyme IgM and IgG. Whole-body computed tomography was unrevealing. The patient was discharged but returned 4 days later with persistent headaches and fever, so he was admitted for further workup.

His past medical history was notable for hypertension, for which he took chlorthalidone, and anxiety, for which he was prescribed paroxetine. Three years earlier, he had completed a 9-month course of isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. He lived with his wife and denied new sexual contacts, as well as use of any alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs.

The patient had not travelled outside of New England following his emigration from Nepal 3 years before. He lived in an urban area and worked as a maintenance worker at a suburban warehouse where he had rodent contact and cut the grass but he denied tick bites. He had visited a farm in Tiverton, RI 4 weeks prior to admission. On that occasion, he handled raw chicken and pork, but he denied ingesting undercooked meat or unpasteurized milk.

Assessment

On admission, the patient's temperature was 106.2° F (41.2° C), and his heart rate was 121 beats per minute. His blood pressure and breathing were normal. He was alert and fully oriented. A head and neck examination was notable for mild scleral icterus, but no neck stiffness or lymphadenopathy was noted. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, abdominal, and neurologic examinations were normal.

Admission biochemistries revealed slight acute kidney injury (creatinine, 1.33 mg/dL). His white blood cell count, hemoglobin, and platelet count were normal. A liver panel demonstrated aspartate transaminase, 72 IU/L; alanine transaminase, 79 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 65 IU/L; and total bilirubin, 1.5 mg/dL, Both the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated at 52 mm/h and 216.65 mg/L, respectively. Urinalysis was unremarkable. Thin and thick smears were negative for parasites. Stool studies for ova and parasites, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter were negative. Seven sets of aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures also remained negative.

Empiric IV vancomycin and ceftriaxone were initiated for possible bacterial meningitis. The following day, the infectious disease service recommended discontinuing those antibiotics in favor of empiric IV doxycycline for possible tick-borne infection. Doxycycline was discontinued when titers for Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Ehrlichia species were negative. Yet, throughout the first week of the patient's hospitalization, his fever continued and his transaminases remained high, with his aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase peaking at 268 IU/L and 227 IU/L, respectively.

An extensive diagnostic workup was conducted to determine the etiology of the patient's fever of unknown origin. It included the following: a viral hepatitis panel (A, B, C, and E); rapid plasma reagin for syphilis; PCR testing of blood samples for human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus; and PCR testing of nasopharyngeal samples for respiratory syncytial virus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, 3, and 4, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, enterovirus, and coronavirus. Tests for urine legionella antigen, Histoplasma capsulatum serum and urinary antigens, and serologies for leptospirosis, leishmaniasis, and Lyme disease were all negative. IgG titers were elevated for dengue fever, Salmonella typhi, varicella, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and Rickettsia typhi, with normal IgM titers for all, a finding consistent with prior exposure. Results of diagnostic testing for noninfectious causes of fever, including antinuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA, and thyroid stimulating hormone, were also unremarkable.

Diagnosis

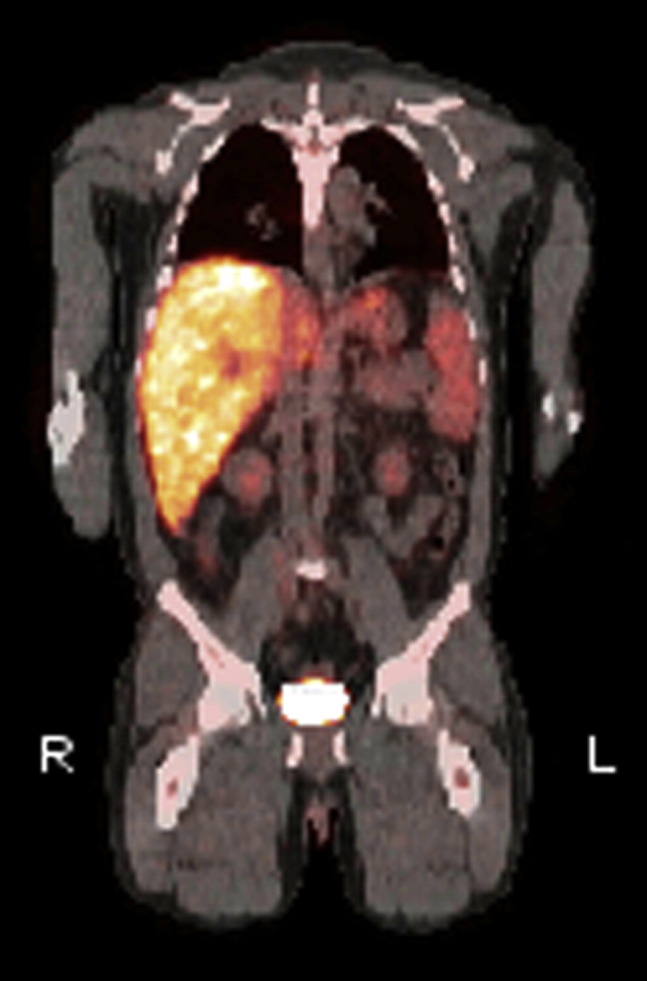

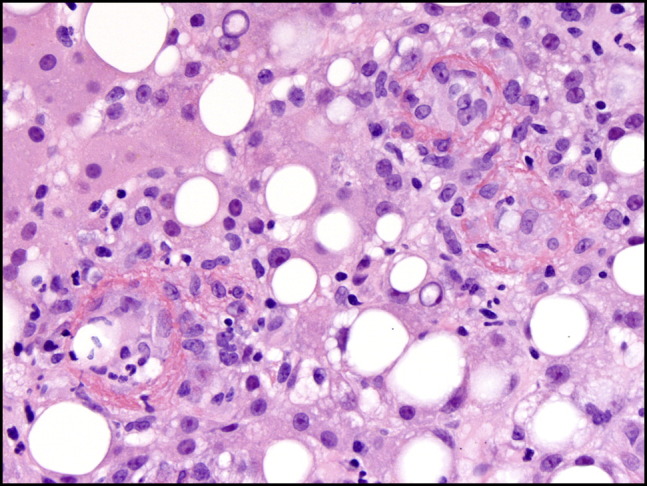

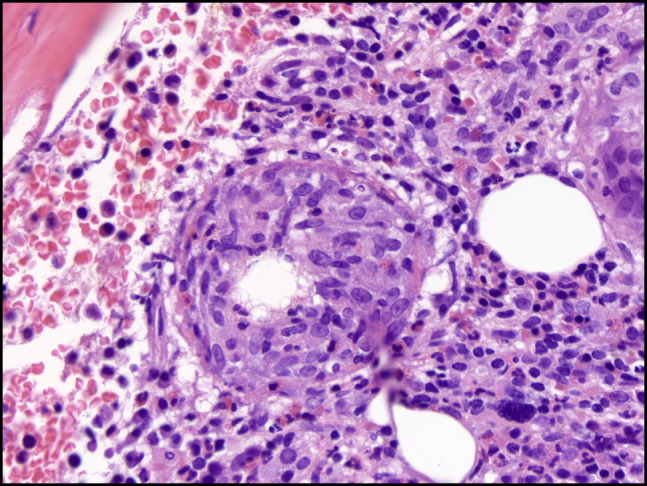

Ongoing nausea, vomiting, and fevers to 107.1° F (41.7° C) prompted a positron emission tomography (PET) scan. Intense diffuse 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was noted in the liver (Figure 1 ). Subsequent liver and bone marrow biopsies demonstrated numerous fibrin ring granulomas (Figures 2 and 3 ), raising suspicion for Coxiella burnetii infection. Serologies confirmed the diagnosis of acute Q fever with phase I and phase II IgM and IgG titers > 256 on indirect immunofluorescence assay (Focus Diagnostics, Inc., Cypress, CA).

Figure 1.

Positron emission tomography demonstrated diffuse 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the liver, an observation consistent with hepatic inflammation.

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a liver biopsy sample showed 3 characteristic fibrin ring granulomas. Inflammatory cells surrounded a central lipid vacuole; a fibrin ring provided the outermost edge.

Figure 3.

Bone marrow biopsy hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrating a fibrin ring granuloma with a central vacuole.

Q fever, originally called query fever, is a zoonotic disease caused by the gram-negative pleomorphic rod C. burnetii. It manifests as self-limited fever, granulomatous hepatitis, and pneumonia in the acute form.1 Infection usually results from inhalation of dust or soil contaminated with livestock waste.1 Many animals, including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, cats, and dogs, are reservoirs for C. burnetii and shed the bacteria in milk, saliva, feces, and urine.2, 3 Infected animals are generally asymptomatic; reproductive abnormalities, such as multiple abortions among members of a herd, can serve as the only evidence of disease. Bacterial concentrations are particularly high in animal products of conception.4 Human-to-human transmission is very rare, but infection via placental and sexual contact has been documented.5, 6 Symptomatic Q fever from ingestion of raw or unpasteurized milk has also been described.7

Human infection, when symptomatic, tends to present as an influenza-like syndrome with general malaise, myalgias, nausea, fevers, and headaches—but up to 60% of acute infections are asymptomatic.2 Moreover, the initial symptoms can differ by geographic location. In certain locales, granulomatous hepatitis is present in 9-67% of cases.8, 9 The characteristic granulomas of Q fever hepatitis have a central lipid vacuole surrounded by histiocytes and lymphocytes; a fibrin ring that is periodic acid-Schiff-positive serves as the outer rim (Figure 2).9, 10 Although classically described in association with Q fever, these lesions are nonspecific and have been identified in numerous diseases, such as leishmaniasis, boutonneuse fever, salmonella, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus infection, Epstein-Barr virus infection, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection, Hodgkin disease, and allopurinol reaction.10

The immunofluorescence assay is the most widely used serologic test for Q fever.2 It identifies phase I and phase II IgM and IgG antibodies to C. burnetii. Phase II IgG antibody titers of ≥ 200 and IgM antibody titers of ≥ 50 indicate acute infection, whereas anti-phase I IgG titers ≥ 800 indicate chronic infection.2

Management

After the pathology results returned, the patient was restarted on doxycycline, 100 mg, twice daily. He demonstrated delayed defervescence, remaining febrile 10 days after restarting the drug, which is not uncommon in Q fever hepatitis.11 Steroid therapy is an option for patients with prolonged pyrexia, as the elevated temperatures may be immunologic.11, 12 Although the pathophysiology of delayed defervescence in Q fever hepatitis is unclear, patients with liver involvement have higher levels of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-10 in comparison to those with fever alone.13 Ultimately, this patient's fevers and elevated transaminases improved, and he was discharged home on doxycycline. When seen 10 days later, he was finishing a 3-week course of the antibiotic, and his symptoms had entirely resolved.

Q fever is rarely diagnosed in the United States, with only 134 cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2011.14 However, seroprevalence of the disease in the United States is approximately 3.1%, suggesting that it is widely under-recognized.15 Because C. burnetii remains a clinically important contributor to fevers of unknown origin worldwide, clinicians should reserve a high index of suspicion for this uncommon disease. Careful histories of exposure could aid in timely diagnosis.

Aimee K. Zaas, MD, Section Editor

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Authorship: All of the authors of this manuscript were directly involved in the care of this patient. CD wrote the first draft with significant revisions performed by BC, EY, EK, and BK. EY provided the photos and pathologic analysis of the case. CD, BC, EK, and BK conducted a literature review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Maurin M., Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:518–553. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter S.R., Czaplicki G., Mainil J. Q Fever: current state of knowledge and perspectives of research of a neglected zoonosis. Int J Microbiol. 2011;2011:248418. doi: 10.1155/2011/248418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/248418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guatteo R., Beaudeau F., Berri M., Rodolakis A., Joly A., Seegers H. Shedding routes of Coxiella burnetii in dairy cows: implications for detection and control. Vet Res. 2006;37:827–833. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roest H.J., van Gelderen B., Dinkla A. Q fever in pregnant goats: pathogenesis and excretion of Coxiella burnetii. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048949. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Racult D., Stein A. Q fever during pregnancy–a risk for women, fetuses, and obstetricians. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:371. doi: 10.1056/nejm199402033300518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milazzo A., Hall R., Storm P.A., Harris R.J., Winslow W., Marmion B.P. Sexually transmitted Q fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(3):399–402. doi: 10.1086/321878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishbein D.B., Raoult D. A cluster of Coxiella burnetii infections associated with exposure to vaccinated goats and their unpasteurized dairy products. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:35–40. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai C.H., Chin C., Chung H.C. Acute Q fever hepatitis in patients with and without underlying hepatitis B or C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:e52–59. doi: 10.1086/520680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee M., Jang J.J., Kim Y.S. Clinicopathologic features of Q fever patients with acute hepatitis. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:10–14. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguilar-Olivos N., del Carmen Manzano-Robleda M., Gutiérrez-Grobe Y., Chablé-Montero F., Albores-Saavedra J., López-Méndez E. Granulomatous hepatitis caused by Q fever: a differential diagnosis of fever of unknown origin. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Alfranca F., Clemente-Rodriguez C., Pigrau-Serrallach C., Fonollosa-Pla V., Vilardell-Tarres M. Q fever associated with persistent fever: an immunologic disorder? Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:122–123. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crespo M., Sopeña B., Bordón J., de la Fuente J., Rubianes M., Martinez-Vázquez C. Steroids treatment of granulomatous hepatitis complicating Coxiella burnetii acute infection. Infection. 1999;27:132–133. doi: 10.1007/BF02560514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honstettre A., Imbert G., Ghigo E. Dysregulation of cytokines in acute Q fever: role of interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor in chronic evolution of Q fever. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:956–962. doi: 10.1086/368129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams D.A., Gallagher K.M., Jajosky R.A., Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC Summary of Notifiable Diseases–United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;60:1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson A.D., Kruszon-Moran D., Loftis A.D. Seroprevalence of Q fever in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:691–694. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]