Presentation

A 44-year-old white woman presented to the hospital with acute shortness of breath while on a flight back to England from a holiday in Turkey. She denied having a productive cough, hemoptysis, or chest or calf pain. She was asthmatic, and her symptoms were improved by repeated administration of her salbutamol inhaler during the flight.

She had a past medical history of nasal polyps that had required surgical intervention 2 years previously.

One month previously she had been treated with a course of amoxicillin for “chronic” otitis media and was awaiting an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialty appointment. She had also developed swollen, tender metacarpophalangeal and ankle joints and was found to have a positive rheumatoid factor. Her symptoms subsequently improved on a short course of prednisolone and she felt well enough to go on holiday.

She worked as a secretary for a law firm, never smoked, and had a long-term partner. She drank a bottle of wine a week. She had no children and had never been pregnant.

Assessment

On presentation she had a temperature of 37.4°C (99.3°F) and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. Her heart rate was 80 beats per minute and blood pressure was 125/67 mmHg. She required oxygen supplied at 10 L/min to maintain her oxygen saturations above 95%. Auscultation of her chest revealed bilateral crackles, and urine dipstick test revealed 3+ blood, 2+ protein, and was negative for pregnancy. The remainder of her physical examination was unremarkable.

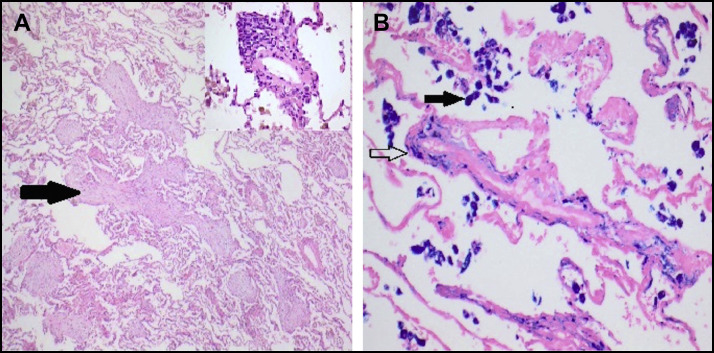

Initial investigation results are shown in Table 1 . Thorax computed tomography (Figure 1 ) demonstrated extensive bilateral patchy air space infiltrates and ground-glass changes but no evidence of embolic disease.

Table 1.

Patient's Initial Investigations on Admission

| Test | Results | Units | Ref. Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 87 | g/L | 120-160 |

| White blood cells | 8.9 | 109/L | 4.0-11.0 |

| Platelets | 678 | 109/L | 150-450 |

| MCV | 85 | Fl | 78-97 |

| Neutrophils | 6.8 | 109/L | 1.7-8.0 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.6 | 109/L | 1.0-4.0 |

| Monocytes | 0.3 | 109/L | 0.24-1.1 |

| Eosinophils | 0.1 | 109/L | 0.1-0.8 |

| INR | 1.4 | Ratio | 0.8-1.1 |

| D-dimer | 1071 | ng/mL | 21-300 |

| Sodium | 136 | mmol/L | 133-146 |

| Potassium | 4.5 | mmol/L | 3.5-5.3 |

| Chloride | 100 | mmol/L | 95-108 |

| Bicarbonate | 24 | mmol/L | 22-29 |

| Urea | 9.4 | mmol/L | 2.5-7.8 |

| Creatinine | 85 | μmol/L | 60-110 |

| eGFR | >60 | mL/min/1.73 m2 | |

| Bilirubin | 12 | μmol/L | 0-21 |

| Alanine transaminase | 33 | U/L | 0-40 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 145 | U/L | 30-130 |

| Albumin | 28 | g/L | 35-50 |

| Gamma glutamyltransferase | 180 | U/L | 0-38 |

| C-reactive protein | 294.1 | mg/L | 0.0-10.0 |

| Arterial pH | 7.4 | 7.35-7.45 | |

| Arterial PO2 on air | 10.0 | kPa | 10.5-13.5 |

| Arterial PCO2 on air | 3.78 | kPa | 4.7-6 |

| Arterial lactate | 2.0 | mmol/L | <1.6 |

| Arterial bicarbonate | 25.0 | mEq/L | 22-26 |

| Urine casts | Negative | – | – |

| Urine PCR | 51 | mg/mmol | <15 |

| Urine white blood cells | 15 | /UL | |

| Urine red blood cells | 2 | /UL | |

| Epithelial cells | 2 | /UL | |

| Urine culture | No growth | – | |

| Chest x-ray study | Patchy air space opacification in the left middle and lower zone and the right mid zone | ||

eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; MCV = mean corpuscular volume; PCR = protein:creatinine ratio.

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography showing extensive bilateral patchy air space infiltrates and ground-glass changes.

Given the history, elevated C-reactive protein, anemia, and diffuse alveolar infiltration, a diagnosis of pulmonary hemorrhage, secondary to an autoimmune or vasculitic process, and a superimposed chest infection was made.

She was transfused with 2 units of blood and treated with intravenous co-amoxiclav and oral doxycycline; 500 mg intravenous methylprednisolone was given over 3 days, then converted to oral prednisolone at 60 mg per day.

Results of viral serology and immunological testing were available on day 3 of admission (Table 2 ). Repeated samples remained serologically negative for any specific autoimmune process.

Table 2.

Viral and Immunological Serology

| Test | Results | Units | Ref. Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A, Influenza B, Parainfluenza, Rhinovirus, | Negative | ||

| Coronavirus, RSV, Metapneumovirus, Adenovirus, | Negative | ||

| Bocavirus, Enterovirus, Parechovirus and | Negative | ||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Negative | ||

| Total protein | 59 | g/L | 60-80 |

| Immunoglobulin G | 10.2 | g/L | 6.0-16.1 |

| Immunoglobulin A | 3.1 | g/L | 0.8-2.8 |

| Immunoglobulin M | 1.0 | g/L | 0.5-1.9 |

| Complement C3 | 1.4 | g/L | 0.75-1.65 |

| Complement C4 | 0.18 | g/L | 0.14-0.54 |

| IgG anti-citrullinated peptide | <1 | U/mL | 0-7 |

| IgG anti-glomerular basement membrane | <3 | U/mL | 0-10 |

| Antinuclear antibody | Negative | ||

| ANCA staining pattern | c-ANCA pattern | ||

| IgG anti-proteinase 3 | <2 | U/mL | Positive >3.0 |

| IgG anti-myeloperoxidase | <2 | U/mL | Positive >5.0 |

| Rheumatoid Factor | 586 | IU/mL | 0-20 |

| IgG anti-SS-A | Negative | ||

| IgG anti-SS-B | Negative | ||

| IgG anti-Smooth Muscle | Negative | ||

| IgG anti-RNP | Negative | ||

| IgG anti-dsDNA | <10 | IU/mL | 0-30 |

| IgG anti-cardiolipin | Negative | ||

| IgG anti-beta-2 glycoprotein 1 | <4 | IU/mL | 0-15 |

c-ANCA = cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; dsDNA = double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid; IgG = immunoglobulin G; RNP = ribonucleoprotein; RSV = respiratory syncytial virus; SS = Sjögren syndrome.

Lung spirometry on day 4 demonstrated a DLCOc (corrected transfer factor) and KCO (transfer coefficient) at 104% and 88% of predicted, respectively.

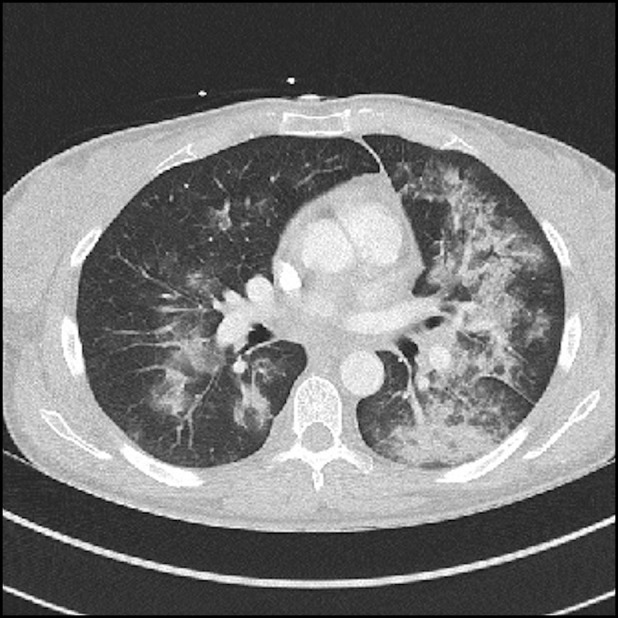

Given the complexity of the case, a lung biopsy was undertaken on day 12 (Figure 2 ). This demonstrated foci of organizing pneumonia with evidence of pulmonary hemorrhage but no active vasculitis.

Figure 2.

Video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy (A) low-power (40×) view of lung demonstrating focal organizing pneumonia (arrow) and subtle perivascular inflammation (insert 200×) (hematoxylin & eosin stain). (B) High-power (200×) view showing coarse haemosiderin deposition within alveolar macrophages (solid arrow) and fine deposition within alveolar septa and the wall of a small blood vessel (open arrow – pulmonary hemosiderosis) (Perls stain).

Our patient improved over the course of 2 weeks and was discharged with a plan to taper her dose of prednisolone. She was seen in the rheumatology clinic 3 weeks post discharge and was found to have haematoproteinuria, with a creatinine of 167 μmol/L (on discharge, this was 80 μmol/L).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) was again negative.

However, during this period our immunology laboratory had noted a discrepancy on ANCA results of a different patient. This second patient had been transferred from another hospital to our renal unit with positive ANCA and positive IgG anti-proteinase 3 antibodies. However, measurement of IgG anti-proteinase 3 antibodies was negative by our local method.

Stored blood samples from our patient were analyzed by alternative methods. The indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) screening by both methods showed a cytoplasmic ANCA staining pattern. However the IgG anti-proteinase 3 levels were <2 U/mL (reference range 0-2 U/mL) by our local method but were 44 U/mL by the alternative method.

Given her renal impairment and active urinary sediment, our patient underwent a renal biopsy (Figure 3 ) that showed pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis consistent with vasculitis.

Figure 3.

Renal biopsy showing evidence of acute necrotizing crescentic glomerulopathy (arrow) with a relatively well-preserved background interstitium (hematoxylin & eosin stain, 200×).

Diagnosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as “Wegener's granulomatosis,” is one of the ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV) typically presenting with upper and lower respiratory tract granulomas and pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. The incidence and prevalence of granulomatosis with polyangiitis in the UK is estimated at 10.2 and 250 cases per million per year, respectively,1 presents most commonly from 35-55 years of age, and has a male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1.2

Since the 1980s, ANCAs have been used as serological markers to aid diagnosis of AAV.3 Most laboratories worldwide use IIF to screen for ANCA. This technique mixes patients' serum with neutrophils. The presence and pattern of any binding by ANCA can then be revealed by subsequent fluorescent staining. A cytoplasmic ANCA staining pattern is typically associated with IgG antibodies to proteinase 3 (PR3) and a perinuclear (p-) pattern to myeloperoxidase (MPO).

The specificity of IIF is high (95%-100%); however, the positive predictive value is only 73%. Significant variability in results occurs due to differences in slide preparation and operator experience, and co-existing inflammatory conditions also cause a high frequency of false positive results.3

In 2003, it was recommended that initial IIF screening for ANCA should be confirmed with a solid phase assay4 such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). However, the clinically significant epitopes of the target antigens PR3 or MPO can be poorly exposed in the ELISA microtiter well,5 leading to falsely low concentrations being reported. Newer assays now use an antibody that binds to a distinct “nonfunctional” epitope of the antigen to “anchor” or “capture” the molecule in the support medium. This allows for increased assay specificity and sensitivity. However, variation in antigen preparation, techniques, and a lack of international reference materials means that there is still significant variation in ANCA results.

Every patient will also make a slightly different IgG antibody to a particular antigen, and the epitopes of the antigen to which a patient responds may also change during the course of a disease or treatment.

A study comparing the different ELISA techniques in healthy controls and patients with known granulomatosis with polyangiitis showed high specificity (>98%) for all methods, but sensitivity varied from 72% with capture ELISA to 96% with anchor ELISA.4

International reference preparations for IgG anti-MPO are prepared and for IgG anti-PR3 are currently in final evaluation, but the full impact of their introduction will take some years. Other components of the ELISA-based techniques will also need to be harmonized (such as the detailed definition of the antigen or epitope being used).

Nevertheless, the discrepancies seen in these assays poses a problem for aiding the diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, particularly in patients with complex or atypical presentations.

Management

Our patient was categorized as having generalized systemic vasculitis and was commenced on a course of remission induction with rituximab infusions and prednisolone, according to the European Vasculitis Society (EUVAS) vasculitis protocol.5

Twelve months after her initial presentation, our patient has had no further episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage, and her creatinine is 127 μmol/L (estimated glomerular filtration rate of 40 mL/min/body surface area). Her prednisolone dose has been subsequently tapered with the introduction of mycophenolate mofetil (2 g per day) to maintain remission.5

This case highlights the potential pitfalls of ANCA testing in the diagnosis of a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Despite improvements in ELISA assay sensitivity and specificity, high inter-method variation exists.

It is important that clinicians appreciate the limitations of these tests and that no single assay will show 100% clinical specificity or sensitivity.

This case highlights the need for good communication with the laboratory when results are surprising or inconsistent with the clinical picture, and that the diagnosis of AAV is a clinical and not a laboratory one. This latter point is reflected by the American College of Rheumatology criteria used to identify granulomatosis with polyangiitis patients for clinical trials, which does not include ANCA results at all.6

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank our patient for allowing for her case to be presented.

Thomas J. Marrie, MD, Section Editor

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Authorship: All authors had full access to data and contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Watts R.A., Scott D.G., Jayne D.R. Renal vasculitis in Japan and the UK – are there differences in epidemiology and clinical phenotype? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(12):3928–3931. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts R.A., Al-Taiar A., Scott D.G. Prevalence and incidence of Wegener's granulomatosis in the UK general practice research database. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(10):1412–1416. doi: 10.1002/art.24544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csernok E., Moosig F. Current and emerging techniques for ANCA detection in vasculitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(8):494–501. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellmich B., Csernok E., Fredenhagen G., Gross W.L. A novel high sensitivity ELISA for detection of antineutrophil cytoplasm antibodies against proteinase-3. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(1):S1–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yates M., Watts R.A., Bajema I.M. EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1583–1594. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leavitt R.Y., Fauci A.S., Bloch D.A. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Wegener's granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:11017. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]