To the Editor:

A 44-year-old man with known compensated chronic hepatitis B was admitted on March 5, 2003, with a 1-week history of malaise, anorexia, and tea-colored urine. On examination, he had jaundice but no other signs of chronic liver disease. He was afebrile and his vital signs were normal. He had thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 124 × 109/L) and a deranged coagulation profile (international normalized ratio: 1.82). Liver function was grossly abnormal (total bilirubin, 6.7 mg/dL; albumin, 3.2 g/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 132 U/L; alanine transaminase, 2090 U/L). Serological tests confirmed hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity. He was hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) negative and anti-HBeAg positive. Both anti-hepatitis C virus and immunoglobulin M anti-hepatitis A virus antibodies were negative. His serum HBV-DNA was 5.1 MEq/mL.

The diagnosis was acute reactivation of chronic hepatitis B. Treatment with lamivudine (100 mg daily) was started. He remained clinically stable with biochemical improvement until day 4, when he developed a fever of 39°C. No focal source of infection was found and his chest radiograph was normal. Despite empirical intravenous cefotaxime and levofloxacin, his fever persisted. A chest radiograph on day 7 showed bilateral air space consolidation. His condition deteriorated the next day, involving respiratory failure and shock, and he was admitted to the intensive care unit. By this time it was apparent that he had contracted severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) during the hospital outbreak of the disease 1, 2. This was subsequently confirmed when SARS-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) was isolated from his nasopharyngeal aspirate. Despite mechanical ventilation and therapeutic intervention that included broad-spectrum antibiotics, ribavirin, and pulse methylprednisolone, his condition worsened and led to multiple system organ dysfunction. The patient died on day 16.

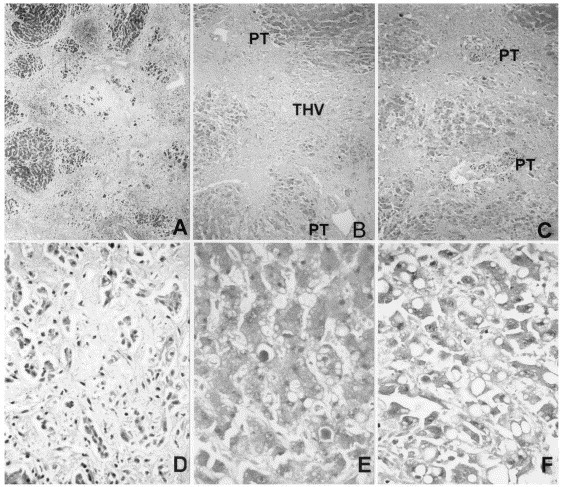

Postmortem examination revealed extensive consolidation in the lungs with diffuse alveolar damage and hyaline membrane, features commonly found in patients who had died of SARS. His liver was cirrhotic and showed severe hepatocyte dropout with small islands of hepatocytes left in the parenchyma (Figure, A). Most of the portal tracts had minimal-to-mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltration with some portal tracts showing lymphocyte depletion (Figure, B and C). There was moderate periportal cholangiolar transformation (Figure, D). Furthermore, severe cholestasis was demonstrated with large bile plugs observed within the bile canaliculi (Figure, E). There was also mild macrovesicular steatosis without accompanying hyaline change (Figure, F). SARS-CoV could not be isolated from the liver tissue.

Figure.

Photomicrographs of the liver necropsy specimen (A: Masson trichrome, ×15; B to F: hematoxylin-eosin, B: ×15, C: ×60, D: ×120, E and F: ×240). PT = portal tract; THV = terminal hepatic vein.

Peiris et al (3) found a higher percentage of patients with HBsAg positivity among SARS patients who developed acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, whether the worse pulmonary outcome was directly related to chronic hepatitis B is not known. In this patient, reactivation of chronic hepatitis B was probably not the major cause of death. The patient was improving until he developed symptoms of SARS. With lamivudine treatment and without SARS, he most likely would have recovered (4). Conversely, his impaired hepatic function might have aggravated the course of SARS and contributed to his death. The interval between the onset of fever and death was much shorter (16 days) than the mean admission-to-death time of 36 days in other SARS patients who had died (2).

The postmortem finding sheds light on the effect of SARS on the patient's hepatitis. Lymphocyte depletion in the portal tracts was unusual because submassive necrosis of liver due to exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B is often associated with prominent lymphocytic infiltration 5, 6. Peripheral lymphopenia is an important feature in SARS and appeared to have affected the liver even in the face of hepatitis. Interestingly, lymphocyte depletion in this patient is reminiscent of hepatic histology in patients with full blown AIDS (7). This may reflect the overwhelming effect of SARS on the immune system. As no SARS-CoV could be isolated from the liver tissue, a direct cytopathic effect of SARS-CoV on the liver was unlikely.

Cytokine dysregulation probably is important in the pathogenesis of SARS, and hence steroid or other immunosuppressive agents have been used as first-line therapy 1, 8. Because immunosuppression may predispose to flare up of chronic hepatitis B, we propose the use of prophylactic antiviral therapy, such as lamivudine, before beginning immunosuppressive treatment in SARS patients with chronic hepatitis B (9). By decreasing the viral load, the likelihood of reactivation of hepatitis B may be reduced. Meanwhile, further studies are warranted to investigate whether chronic hepatitis B has any effect on the prognosis of SARS.

References

- 1.Lee N., Hui D., Wu A. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnelly C.A., Ghani A.C., Leung G.M. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361:1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peiris J.S.M., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C.C. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan H.L., Tsang S.W., Hui Y. The role of lamivudine and predictors of mortality in severe flare-up of chronic hepatitis B with jaundice. J Viral Hepatol. 2002;9:424–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J.W., Lee H.S., Woo G.H. Fatal submassive hepatic necrosis associatedwith tyrosine-methionine-aspartate-aspartate-motif mutation of hepatitis B virus after long-term lamivudine therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:403–405. doi: 10.1086/321879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maguire C.M., Crawford D.H., Hourigan L.F. Case report: lamivudine therapy for submassive hepatic necrosis due to reactivation of hepatitis B following chemotherapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:801–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakanuma Y., Liew C.T., Peters R.L., Govindarajan S. Pathologic features of the liver in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Liver. 1986;6:158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1986.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholls J.M., Poon E.L.M., Lee K.C. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo W., Steinberg J.L., Tam J.S. Lamivudine in the treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Med Virol. 1999;59:263–269. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199911)59:3<263::aid-jmv1>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]