Abstract

This review provides a practical, simple, and logical approach to the diagnosis and management of patients with acute infectious diarrhea, one of the most common diagnoses in clinical practice. Diarrhea in the immunocompromised host, traveler’s diarrhea, and diarrhea in the hospitalized patient are also discussed. Most episodes of acute diarrhea are self-limited, and investigations should be performed only if the results will influence management and outcome. After an adequate history and physical examination, the clinician should be able to classify the acute diarrheal illness, assess the severity, and determine whether investigations are needed. Most patients do not require specific therapy. Therapy should mainly be directed at preventing dehydration. Various home remedies frequently suffice in mild, self-limited diarrhea. However, in large-volume, dehydrating diarrhea, oral rehydration solutions should be used, as they are formulated to stimulate sodium and water absorption. Antidiarrheal agents can be useful in reducing the number of bowel movements and diminishing the magnitude of fluid loss. The most useful agents are opiate derivatives and bismuth subsalicylate. Antibiotic therapy is not required in most patients with acute diarrheal disorders. Guidelines for their use are presented.

Diarrhea is defined as the production of stools of abnormally loose consistency, usually associated with excessive frequency of defecation and with excessive stool output 1, 2. Normal stool output is approximately 100 to 200 g/day. Although diarrhea is a common symptom, most cases are self-limited or successfully treated by patients with over-the-counter medications.

Acute diarrhea, defined as diarrhea that has been present for <4 weeks (2), is a nonspecific response of the intestine to several different conditions, including infections, adverse reactions to drugs, inflammatory bowel disease, and ischemia. The specific drugs and poorly absorbed sugars that can cause acute diarrhea are discussed by Fine et al (1). Although most cases of diarrhea are a result of infections (Table 1 ), specific organisms can be identified in only a minority of patients. Patients seek medical attention for diarrhea when it is severe, prolonged, or if they develop worrisome symptoms, such as fever, prostration, or rectal bleeding.

Table 1.

Causes of Acute Infectious Diarrhealegend

| Viruses | Bacteria | Protozoa |

|---|---|---|

| Rotavirus | Shigella | Giardia lamblia |

| Norwalk virus | Salmonella | Entamoeba histolytica |

| Norwalk-like agents | Campylobacter | Cryptosporidium |

| Enteric adenovirus | Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli | Cyclospora |

| Calcivirus | Enterohemorrhagic E. coli | |

| Astrovirus | Enteroinvasive E. coli | |

| Small round viruses | Enteropathogenic E. coli | |

| Coronavirus | Yersinia | |

| Herpes simplex virus | Clostridium difficile | |

| Cytomegalovirus | Clostridium perfringens | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| Bacillus cereus | ||

| Vibrio | ||

| Chlamydia | ||

| Treponema pallidum | ||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | ||

| Aeromonas | ||

| Pleslomonas shigelloides |

Modified from (7).

Acute infectious diarrhea is acquired predominantly through the fecal–oral route and by the ingestion of water and food contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms. Once ingested, these microorganisms must overcome host defense mechanisms, including gastric acid (the low pH of the normal stomach is bactericidal for most bacterial enteropathogens); local and systemic immune mechanisms, such as gut-associated lymphoid tissue, elaboration of immunoglobulins, and defensins (cryptdins) that provide cellular and humoral protection against microorganisms; and gastrointestinal motility, which impairs the ability of microorganisms to adhere to the mucosa.

Epidemiology of acute infectious diarrhea

Acute diarrhea is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in pediatric and geriatric patients. In underdeveloped countries, the incidence and mortality of acute diarrhea is greatest in children. In Latin America, for example, the incidence is approximately 2.7 diarrheal episodes per year in the first 2 years of life (3). Factors thought to increase morbidity and mortality in developing countries have been reviewed (4). Acute diarrhea is also a common problem in the United States and Western Europe, with an incidence of approximately one episode per person per year (5). A comparison of common causes of acute infectious diarrhea in the western world and less-developed countries is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical Presentations and Likely Causes of Acute Diarrheal Disease in Outpatientslegend

| Clinical Type | Approximate Percentage of Patients | Likely Cause |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrialized Countries | Less-developed Countries | ||

| Watery diarrhea | 90 | Rotavirus, other viruses | Rotavirus, Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, Enteropathogenic E. coli, Campylobacter jejuni |

| Dysentery | 5 to 10 | Shigella, Enteroinvasive E. coli, Campylobacter jejuni | Shigella, Enteroinvasive E. coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Entamoeba histolytica |

| Protracted diarrhea (>14 days) | 3 to 4 | Enteropathogenic E. coli, Giardia, Yersinia | Enteropathogenic E. coli, Giardia |

| Severe purging with rice-water stool | 1 (higher in cholera-endemic areas) | Salmonella, Enterotoxigenic E. coli | Vibrio cholerae, Enterotoxigenic E. coli |

| Hemorrhagic colitis | <1? | Enterohemorrhagic E. coli | Enterohemorrhagic E. coli |

Modified from (6).

Several special situations, including hospital-acquired diarrhea, traveler’s diarrhea, and diarrhea in the immunocompromised host, are discussed separately.

Evaluation of the patient

Because many conditions cause acute and chronic diarrhea, it is useful to classify the diarrheal illness into one of two clinical syndromes, either a watery, noninflammatory diarrheal syndrome, or an inflammatory diarrheal syndrome (8). This classification can usually be made clinically and with simple, inexpensive diagnostic tests.

In the United States, most patients with watery, noninflammatory diarrhea have an illness that is self-limited and that does not require specific therapy. Evaluation of such patients is generally unrewarding and usually unnecessary. In contrast, in many patients with acute inflammatory diarrhea, a specific pathogen can be diagnosed, and the patient may benefit from antibiotic therapy.

The noninflammatory diarrheal syndrome is characterized by watery stools that may be of large volume (>1 L per day), without blood, pus, severe abdominal pain, or fever. This type of diarrhea is caused by bacteria, such as Vibrio cholerae, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, and staphylococcal and clostridial food poisoning; viruses, such as Rotavirus and Norwalk agent; and protozoa, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Infection with these agents can alter the normal absorptive and secretory processes of the enterocyte, leading to watery diarrhea. Many organisms cause these changes because they elaborate enterotoxins. In this syndrome, the morphology of the mucosa remains normal or is only minimally altered. Thus, stools do not have fecal leukocytes (or only a few) or occult blood.

The inflammatory diarrheal syndrome is characterized by frequent, small-volume, mucoid or bloody stools (or both), and may be accompanied by tenesmus, fever, or severe abdominal pain. The causative organisms induce an acute inflammatory reaction in the small or large intestine, and the stools may have many leukocytes and, frequently, occult or gross blood. Fecal polymorphonuclear leukocytes (or a positive stool lactoferrin test) indicate the existence of an acute inflammatory process in the gastrointestinal tract. The greater the number of leukocytes, the lower in the gastrointestinal tract is the inflammatory focus. When sheets of leukocytes are seen in stool specimens, the disease is in the colon. Infectious causes of this syndrome include Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, enterohemorrhagic E. coli, enteroinvasive E. coli, C. difficile, E. histolytica, and Yersinia. The acute inflammatory diarrheal syndrome can also be of noninfectious etiology, such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, radiation or ischemic colitis, or diverticulitis (9).

An adequate medical history and a complete physical examination are essential in determining the possible diagnoses, degree of severity, and complications, and to suggest further investigations. Table 3 lists specific historic clues to the diagnosis of acute diarrhea.

Table 3.

Specific Historical Clues to the Etiologic Diagnosis of Acute Diarrhealegend

| History | Possible Enteric Pathogens | Additional Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Bloody stools | Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, Clostridium difficile, E. histolytica | Stool specimen for culture, ova and parasites, and C. difficile toxin |

| Recent antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy | C. difficile, Salmonella | Stool specimen for C. difficile toxin |

| Travel (Mexico, Africa, Middle or Far East) | Enterotoxigenic E. coli, and other bacterial pathogens and parasites | Stool for ova and parasites |

| Several family or friends similarly affected | Various food poisoning syndromes: | None usually required |

| Staphylococcus, Clostridium, Bacillus cereus, Salmonella | ||

| Homosexual males | Herpes, Chlamydia, syphilis, E. histolytica, Shigella, Giardia, gonococcus, Cryptosporidium | Sigmoidoscopy; rectal biopsy; stool specimen for ova and parasites; culture for gonococcus, herpes, and chlamydia; serologic test for syphilis |

| Rectal pain, severe tenesmus | Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, | As above for homosexual males |

| Gonococcus, Herpes, Chlamydia, E. histolytica | ||

| Severe or persistent abdominal pain | Campylobacter, Yersinia, Clostridium | Notify laboratory for special culture |

| perfringens, Aeromonas | ||

| Hospital-acquired | C. difficile, elixirs, drugs | Stool specimen for C. difficile toxin |

| Day-care centers, mental institutions | Giardia, C. difficile, Salmonella, Shigella, rotavirus | Stool for ova and parasites, culture, C. difficile toxin |

Modified from (7).

Special situations

Diarrhea in the immunocompromised patient

The state of the host immune system should be considered in a patient with infectious diarrhea. Common causes of an impaired host immune system include IgA deficiency, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), immunosuppressive therapy after organ transplantation, and use of corticosteroids. These patients are more susceptible to conventional microorganisms, as well as to unusual organisms, such as Cryptosporidium, Microsporidium, Isospora belli, Cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (10). Infection in immunocompromised patients may also be more severe, more likely to have complications, and more recalcitrant to treatment (10).

Traveler’s diarrhea

Traveler’s diarrhea affects 10 million people each year. The areas of most frequent occurrence are Mexico, Central and South America, the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. The likelihood of acquiring traveler’s diarrhea in these areas is 30% to 50%. Traveler’s diarrhea can be caused by several pathogens, the most common of which is enterotoxigenic E. coli. However, several other organisms, including Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Giardia, Entamoeba histolytica, and rotavirus, also cause this syndrome 11, 12. Diarrhea usually occurs within days of arriving at the destination, although it may not begin until after returning home. The basic principles of diagnosis are the same as those described previously.

Although there are effective antibiotic regimens for the prophylaxis of traveler’s diarrhea, they are not recommended for most travelers, because most cases are self-limited. Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) is a safe and efficacious treatment for mild traveler’s diarrhea 12, 13. More severe or prolonged cases respond to therapy with a quinolone antibiotic. Occasionally, however, the diarrhea can persist, leading to a chronic diarrheal syndrome characterized by temporary malabsorption that ultimately resolves, a chronic malabsorptive syndrome that is similar to tropical sprue, or an illness that mimics irritable bowel syndrome (14).

Hospital-acquired diarrhea

Acute diarrhea in a hospitalized patient may be a result of infection with Clostridium difficile, the ingestion of elixirs containing sorbitol or mannitol (such as acetaminophen or theophylline), a medication side effect, or as a consequence of tube feedings. Thus, routine stool examination for enteric pathogens and for ova and parasites is usually unrewarding and not cost-effective.

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea as a result of C. difficile infection is the most common cause of acute diarrhea in hospitalized patients 15, 16. Diarrhea can range from mild illness to life-threatening disease associated with pseudomembranous colitis. It can follow treatment with almost any enteral or parenteral antibiotic. Thus any hospitalized patient who develops diarrhea, especially if the patient had been treated with a cephalosporin or clindamycin, should be evaluated for the presence of C. difficile toxin. Tissue culture cytotoxicity has a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 98%, and the results are available in 1 to 2 days. Rapid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests for toxins A and B have a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 100%. The results are available in <1 hour (17). Patients usually respond promptly to treatment with oral metronidazole or oral vancomycin, although approximately 10% to 20% of treated patients have a relapse of symptoms, usually within 5 weeks after completion of therapy. These patients may be treated with a second course of metronidazole or vancomycin, or therapy may be changed to another antibiotic, such as oral bacitracin or rifampin.

Diarrheagenic escherichia coli

This term refers to five types of E. coli that have specific clinical and epidemiologic features: enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteroadherent E. coli (EAEC), and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). Enterotoxigenic E. coli produce disease by adherence to the mucosa and the production of toxins, which may be heat labile or heat stable. Their distribution is worldwide and accounts for most cases of traveler’s diarrhea. Enteropathogenic E. coli have been associated primarily with diarrhea in children <2 years old, although they can cause traveler’s diarrhea. Enteroinvasive E. coli can invade mucosa and can produce a dysentery-like syndrome similar to Shigella. Enteroadherent E. coli are the most poorly understood; they may cause persistent diarrhea in children. These four types of diarrheagenic E. coli are rarely diagnosed, because the necessary laboratory tests are not routinely available. Infection with enterohemorrhagic E. coli is characterized by colitis with bloody diarrhea (hemorrhagic colitis), which may be complicated by the hemolytic-uremic syndrome or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Although it can be caused by different serotypes of E. coli that elaborate Shiga-like toxins, serotype 0157:H7 is the most common type. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli infection is both endemic and epidemic in the United States. It is transmitted by food, most commonly ground meat, and it can be isolated easily by hospital laboratories, through the use of Sorbitol-MacConkey agar and specific typing serum. An ELISA for detection of Shiga-like toxin(s) in stool is available but not yet in routine use.

Diagnostic testing

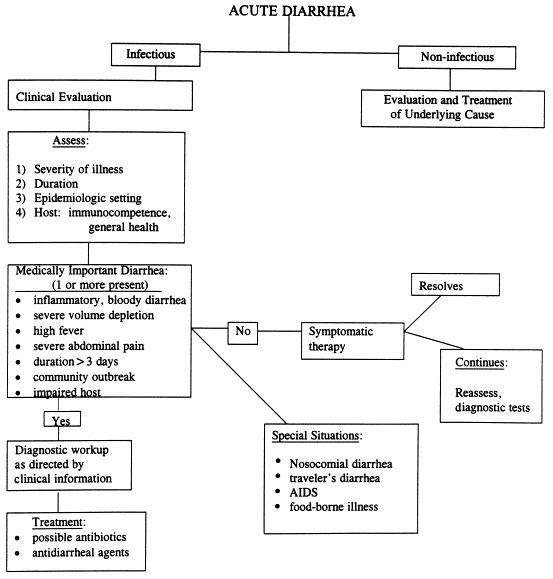

After an adequate medical history and physical examination, the clinician should be able to classify the acute diarrheal illness and determine its severity and possible complications 18, 19. The clinician should also be able to determine whether any diagnostic tests are needed 18, 20. Because most episodes of acute diarrheal illness in the United States are self-limited, diagnostic testing should be kept to a minimum. Treatment should be aimed at preventing dehydration. Investigations should be focused toward the diagnosis of specific pathogens as suggested by the history. It is not appropriate to send the entire array of stool cultures and stool examination for every patient. They should be performed only if their results will influence management and outcome. Diagnostic testing should be reserved for patients with severe illness (large volume dehydrating diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, or more than a 3-day course); patients with inflammatory diarrhea who have bloody stools or systemic symptoms, such as fever >38.3°C or prostration; patients with recent travel to high-risk areas; and immunocompromised patients (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Approach to the patient with acute diarrhea. The goal of the initial evaluation is to distinguish medically important diarrhea from benign self-limited diarrhea. By focusing on four categories of information—the severity of illness, the duration of diarrhea, the setting in which diarrhea was obtained, and the state of host defenses and immunity—the clinician can decide which patients require additional investigation and treatment. Modified from (17).

Diagnostic tests for acute infectious diarrhea in the normal host include stool cultures for bacterial pathogens, stool examination for ova and parasites, and stool testing for Clostridium difficile toxin and for E. coli 0157:H7. In most microbiology laboratories, stool sent for culture of enteric pathogens will be processed for Shigella, Salmonella, andCampylobacter. Other enteric pathogens such as Yersinia, Vibrio, and E. coli 0157:H7 are not routinely sought. Therefore, if the clinical suspicion for these organisms is high, the microbiology department needs to be notified. If the medical history suggests risk factors for C. difficile, such as recent antibiotic exposure, recent hospitalization, day-care exposure, or recent chemotherapy, stool should be tested for C. difficile toxin. More invasive investigations, including flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with duodenal aspirate and biopsies, are reserved for special situations, such as an immunocompromised patient in whom stool examination has not yielded a diagnosis (Table 3).

Therapy

Supportive therapy and oral hydration

Most cases of acute diarrhea are self-limited, and specific therapy is not necessary. Therapy should be directed at preventing dehydration and restoring fluid losses. Although this is often done intravenously, it can also be accomplished with oral fluid–electrolyte therapy. Oral intake should be encouraged to minimize the risk of dehydration. The misconception that the bowel needs to be at rest or that oral intake will worsen the diarrheal illness should be abandoned. It is important, however, to avoid milk and other lactose-containing products, because viral or bacterial enteropathogens often result in transient lactase deficiency, leading to lactose malabsorption. Caffeine-containing products should be avoided, because caffeine increases cyclic AMP levels, thus promoting secretion of fluid and worsening diarrhea.

Various home remedies include cola beverages, Gatorade, fruit juices, and soft drinks. These are commonly used and frequently suffice in patients with mild, self-limited diarrhea. However, in patients with dehydration or large-volume diarrhea, these remedies should be avoided, because the fluids are hyperosmolar and deficient in electrolytes and thus are poor replacements for diarrheal losses. Rather, glucose-containing electrolyte solutions should be used. Glucose in the intestinal lumen facilitates the absorption of sodium and, thereby, of water (7). This co-transport mechanism is usually unaffected by infectious microorganisms or their toxins. Several oral rehydration solutions have been developed to take advantage of the glucose-sodium–coupled transport mechanism (Table 4 ). Several are commercially available and are strongly recommended for use in adults as well as children.

Table 4.

Composition of Oral Replacement Solutions for the Treatment of Diarrhealegend

| Solution | Sodium mmol/L | Potassium mmol/L | Chloride mmol/L | Citrate mmol/L | Glucose∗ mmol/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO solution | 90 | 20 | 80 | 30 | 111 (20) |

| Rehydralyte | 75 | 20 | 65 | 30 | 139 (25) |

| Pedialyte | 45 | 20 | 35 | 30 | 139 (25) |

| Resol | 50 | 20 | 50 | 34 | 111 (20) |

| Ricelyte | 50 | 25 | 45 | 34 | (30) |

| Gatorade | 23.5 | <1 | 17 | (40) | |

| Coca-Cola | 1.6 | <1 | 13.4† | (100) | |

| Apple juice | <1 | 25 | (120) | ||

| Orange juice | <1 | 50 | 50 | (120) | |

| Chicken broth | 250 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

Figures in parentheses represent grams of carbohydrate.

Rice syrup solid rather than glucose.

Modified from (2).

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy with antidiarrheal agents for acute infectious diarrhea can reduce the number of bowel movements and diminish the magnitude of fluid and electrolyte loss. The most commonly used agents include opiates and opiate derivatives (loperamide and diphenoxylate), bismuth subsalicylate, and kaolin-containing agents. The major effect of opiate derivatives is to slow the intestinal transit time, although they also possess a pro-absorptive or antisecretory effect in the intestine (21). Anticholinergic agents are not effective for controlling symptoms and may cause significant adverse side effects. They are therefore not recommended. Adsorbent agents such as Kaopectate (Attapulgite) and stool texture modifiers are used frequently in over-the-counter medications, but their efficacy is uncertain.

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) is safe and efficacious in the treatment of infectious bacterial diarrhea. It stimulates intestinal sodium and water reabsorption, binds enterotoxins, and has a direct antibacterial effect (13). The concern that agents that decrease intestinal transit time are contraindicated in invasive infectious diarrhea has been greatly overstated. The use of these compounds in such patients is generally safe. If patient discomfort is substantial, the physician should not hesitate to recommend a short course of these agents.

Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy is not required in most acute diarrheal disorders 22, 23. Patients with mild disease who have no complications and who are clinically improving do not need antibiotic therapy. Infectious diarrheal illness as a result of viruses or cryptosporidiosis has no effective therapy. However, treatment is recommended for Shigellosis, traveler’s diarrhea, pseudomembranous enterocolitis, Cholera, sexually transmitted diseases, and parasites. The usefulness of antibiotic therapy for other organisms, such as Yersinia, Campylobacter, and outbreaks of enteropathogenic E. coli, is less clear but is generally recommended (Table 5 ). Specific antibiotics and dosages are discussed in a recent review (23). However, because of the widespread use of antibiotics, many isolates of C. jejuni, Shigella, and Salmonella are resistant to many antibiotics. Thus, the choice of antibiotics should, whenever possible, be based on the antibiotic sensitivity patterns in the patient’s community.

Table 5.

Indications for Antimicrobial Agents in Diarrheal Disease of Established Causelegend

| Clearly indicated | Indicated in Some Situations | Not Indicated |

|---|---|---|

| Shigellosis Cholera | Nontyphoidal salmonellosis in infants <12 weeks of age and immunocompromised hosts) | Rotavirus infection Other viral infections |

| Traveler’s diarrhea∗ | Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (nursery outbreaks) | Nontyphoidal salmonellosis |

| Amebiasis | Enteroinvasive E. coli | Cryptosporidiosis |

| Giardiasis | Campylobacter (early treatment of dysentery) | |

| Cyclospora | Clostridium difficile colitis | |

| Yersinia (protracted infection) | ||

| Noncholera vibrio |

Enterotoxigenic E. coli is the most common cause of acute traveler’s diarrhea, and certain antibiotics, such as quinolones, are highly effective.

Modified from (6).

References

- 1.Fine K.D, Krejs G.J, Fordtran J.S. Diarrhea. In: Sleisenger M.H, Fordtran J.S, editors. Gastrointestinal Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 6th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1998. pp. 1043–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell D.W. Approach to the patient with diarrhea. In: Yamada T, Alpers D.H, Owyang C, Powell D.W, Silverstein F.E, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 2nd ed. JB Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1995. pp. 813–831. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prado V, O’Ryan M.L. Acute gastroenteritis in Latin America. Infect Dis Clin of North Am. 1994;8:77–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuPont H.L. Diarrheal diseases in the developing world. Infect Dis Clin of North Am. 1995;9:313–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman R, Banatvala N. The frequency of culturing stools from adults with diarrhea in Great Britain. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:41–44. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005144x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiJohn D, Levine M.R. Treatment of diarrhea. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1988;2:719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaunitz J.D, Barrett K.E, McRoberts J.A. Electrolyte secretion and absorption: small intestine and colon. In: Yamada T, Alpers D.H, Owyang C, Powell D.W, Silverstein F.E, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 2nd ed. JB Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1995. pp. 326–361. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannella RA. Gastrointestinal infections. In: Kelley WN, ed. Textbook of Internal Medicine. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1989:554–562.

- 9.Farmer R.G. Infectious causes of diarrhea in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30584-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Gastroenterological Association technical review Malnutrition and cachexia, chronic diarrhea and hepatobiliary disease in patients with human immunodeficiency viral infection. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1724–1752. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor D.N, Echeverria P. Etiology and epidemiology of traveler’s diarrhea in Asia. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8(suppl 2):136–141. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.supplement_2.s136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DuPont H.L, Ericcson C.D. Prevention and treatment of traveler’s diarrhea. NEJM. 1993;328:1821–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306243282507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steffen R. Worldwide efficacy of bismuth subsalicylate in the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(suppl 1):80–86. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_1.s80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannella R.A. Chronic diarrhea in travelers: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8(suppl 2):223–226. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.supplement_2.s223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarland L.V, Mulligan M.E, Kwok R.Y.Y, Stamm W.E. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. NEJM. 1989;320:204–210. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901263200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel D, Edelstein P.H, Nachamkin I. Inappropriate testing for diarrheal diseases in the hospital. JAMA. 1990;263:979–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyerly D.M, Neville L.M, Evans D.T. Multicenter evaluation of the Clostridium difficile TOX A/B test. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:184–190. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.184-190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S.I, Giannella R.A. Approach to the adult patient with acute diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clinics North Am. 1993;22:483–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuPont H.L. Guidelines on acute infectious diarrhea in adults. The practice parameters committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1962–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talal A.H, Murray J.A. Acute and chronic diarrhea. How to keep laboratory testing to a minimum. Postgrad Med. 1994;96:30–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiller L.R. Review article: anti-diarrhoeal pharmacology and therapeutics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:87–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuPont H.L. Review article: infectious diarrhea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:3–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf D.C, Giannella R.A. Antibiotic therapy for bacterial enterocolitis: a comprehensive review. Am J Gastroent. 1993;88:1667–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]