To the Editor:

Dr. Augustine's1 admonishment in the January 2004 issue of Annals on the potential shortcomings of the current emergency care system in dealing with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pointed out the need for increased emergency department (ED) vigilance. Having reported the first SARS case in Taiwan and fought the consecutive cluster outbreaks in the nearby hospitals, our hospital encountered what Dr. Augustine describes. Therefore, we would like to share the 3 main problems we encountered during the outbreak of SARS; namely, ED staff management, ED overload from patients with airway symptoms but who were unaffected by SARS, and the prolonged stay of highly contagious patients in the ED waiting to be admitted.

First, the recent trend of hospital retrenchment has taken its toll in the face of health catastrophes.1 The situation was worsened by the highly contagious nature of SARS, which took many health care providers off their services for quarantine purposes. After the endemic outbreak of SARS, manpower shortages rapidly became worse. Fourteen of our fellow staff members (4 physicians and 10 nursing staff) were kept in quarantine because they had interacted with SARS patients without proper protection.

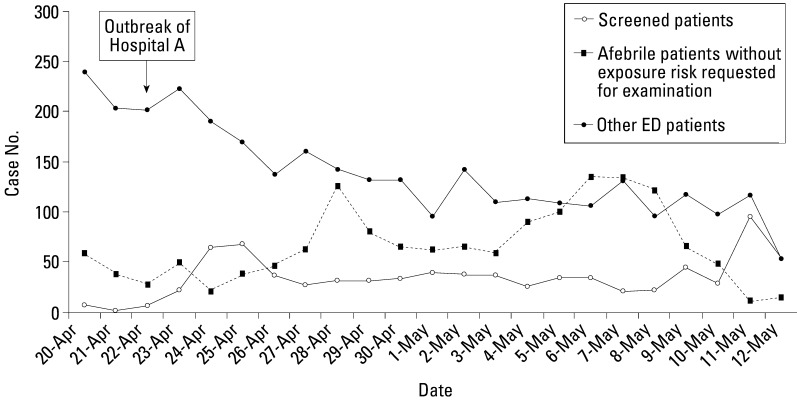

Second, the surge of patients became challenging. A large number of individuals who had no documented fever or exposure history presented to the ED with minimal airway symptoms. These “worried-well” patients with multiple unexplained physical symptoms outnumbered the patients with actual exposure risk (from April 22 to May 12, 2003, 1,421:789) (Figure 1 ). The conditions became more complicated with the presence of SARS patients who had no traceable contact history. Providers of emergency medical services were forced to treat every patient with an equal level of vigilance and an equal amount of time. The necessity of clarifying the chronological symptomatology of SARS and of developing a set of prediction rules for triaging SARS among febrile patients became imperative.2., 3., 4.

Figure 1 (Chen).

ED patient category.

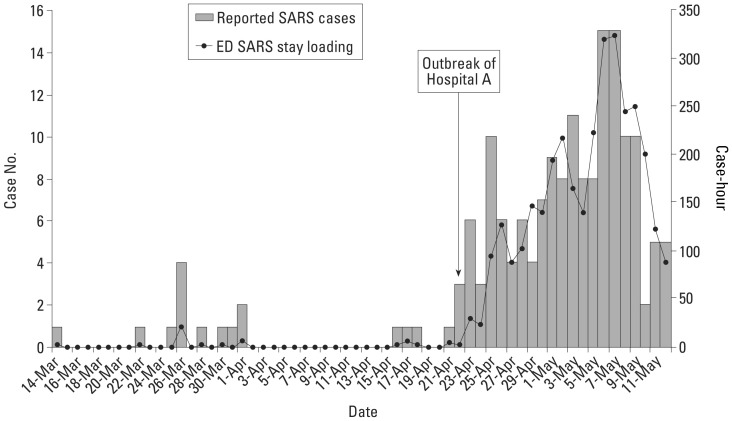

Finally, EDs and hospitals alike were endangered when crowded with highly contagious patients waiting to be admitted. In March 2004, the Taiwan Center for Disease Control policy required that all suspected SARS patients be admitted to respiratory isolation rooms to eliminate any possibility of nosocomial transmission. After the endemic outbreak and the pouring of patients into our ED, adhering to this policy created a huge burden on the ED staff because the average length of stay in the ED waiting for the opening of isolation rooms increased from an average of 3.1 to 23.1 hours (Figure 2 ). For ED staff, prolonged stay and crowding of SARS patients increased the risks of exposure to the virus from the patients and the environment. Tests for SARS-coronavirus polymerase chain reaction were positive in 7.6% (9/119) of our ED environmental samples. To lessen the risk of facility contamination, outdoor screening stations were later set up to alleviate the environmental viral burden when a large number of febrile patients from the community had to be screened.5

Figure 2 (Chen).

ED SARS loading.

Dr. Augustine1 has the foresight to point out the current deficiency of emergency medical services in dealing with the SARS epidemic. Our experience echoed his argument. The emergency medical services community should learn from the experience of their colleagues in combating SARS and prepare themselves for the next public health catastrophe.

References

- 1.Augustine J.J., Kellermann A.L., Koplan J.P. America's emergency care system and severe acute respiratory syndrome: are we ready? Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S.-Y., Su C.-P., Ma M.H.-M. Predictive model of diagnosing probable cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in febrile patients with exposure risk. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(03)00817-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su C.-P., Chiang W.-C., Ma M.H.-M. Validation of a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome scoring system. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S.-Y., Su C.-P., Ma M.H.-M. Sequential symptomatic analysis in probable severe acute respiratory syndrome cases. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tham K.-Y. An emergency department response to severe acute respiratory syndrome: a prototype response to bioterrorism. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]