Presentation

A patient's symptoms and travel history suggested that he might have Middle East respiratory syndrome, a frightening and often fatal viral infection. The man, who was aged 44 years and Caucasian, presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever and dry cough. He also had a sore throat, headache, and mild epigastric discomfort. In addition, he had noticed a skin rash on the day of admission. He returned from a business trip to the United Arab Emirates 10 days earlier, but he recalled no contact with animals or sick people. Until this illness, he had enjoyed good health.

Assessment

On admission, the patient had a fever of 100°F (37.8°C). Physical examination revealed a generalized, blanchable, macular rash over his trunk, with sparing of the limbs, head, and neck (Figure 1 ). Chest auscultation disclosed inspiratory crackles over the right lower zone. Results of a complete blood count showed a total leukocyte count of 6.19 × 103 cells/mm3, hemoglobin of 15.2 g/dL, and a platelet count of 175 × 103 platelets/μL. The patient's neutrophil count was normal at 5.01 × 103 cells/mm3, but mild lymphopenia (0.91 × 103 cells/mm3) was noted. Liver function was mildly deranged, as demonstrated by elevations in serum alanine aminotransferase (60 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (62 U/L). Serum bilirubin was normal at 0.76 mg/dL (13 μmol/L), as was alkaline phosphatase at 73 U/L.

Figure 1.

The patient had a generalized, blanchable, macular rash over his trunk.

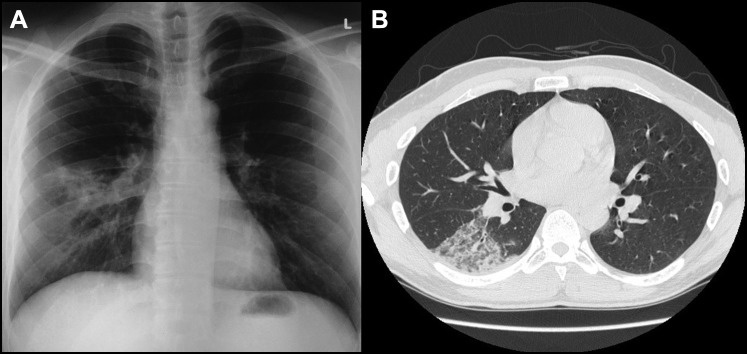

The patient's erythrocyte sedimentation rate (20 mm/h) and serum C-reactive protein level (3.8 mg/dL) were mildly elevated. A chest radiograph showed right middle zone haziness (Figure 2 ). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the thorax displayed ground-glass changes in the lower lobe of the right lung (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Chest radiograph shows right middle zone haziness. (B) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the thorax demonstrates a ground-glass appearance in the right lower lobe of the lung.

A diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia was made. Because the patient had traveled to the Arabian Peninsula 10 days before symptom onset, he was admitted under airborne infection isolation precautions for suspected Middle East respiratory syndrome. However, a nasopharyngeal aspirate tested negative by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction or indirect immunofluorescence for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, other coronaviruses, influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, and adenovirus. All were eliminated from the differential diagnosis.

Polymerase chain reaction testing of the nasopharyngeal aspirate for pathogens of atypical pneumonia, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila, also provided negative results. Sputum and blood cultures were negative, as were a urine sample tested for L. pneumophila serogroup 1 antigen, the serum Monospot test for infectious mononucleosis, and a human immunodeficiency virus antibody test.

On further exploration of contact history, the patient reported an episode of roseola infantum, commonly referred to as roseola, in his 15-month-old daughter 5 weeks earlier. Another nasopharyngeal aspirate sample was retrieved, and this tested positive for human herpesvirus 6 DNA with polymerase chain reaction primers targeting the U67 gene. Sequencing confirmed the virus to be human herpesvirus 6B. Serum obtained on day 4 after symptom onset was negative for human herpesvirus 6B DNA.

Diagnosis

The patient's diagnosis, atypical pneumonia caused by human herpesvirus 6B, was based on several lines of evidence, including recent contact with his child, who had suspected roseola, also known as “exanthema subitum” or “sixth disease.” This common and often self-limiting pediatric ailment is caused by human herpesvirus 6. Other considerations were the development of a characteristic roseola-like macular skin rash after 2 days of fever, the lack of evidence of other bacterial or viral causes of pneumonia, and the detection of human herpesvirus 6B DNA in a nasopharyngeal aspirate during the symptomatic phase. His illness demonstrates that human herpesvirus 6B can cause pneumonia mimicking other forms of viral pneumonia in immunocompetent individuals.

Descriptions of human herpesvirus 6B pneumonia are rare among immunocompetent patients. One report of an immunocompetent adult with severe legionellosis details the concurrent isolation of human herpesvirus 6B antigens from blood and from inflammatory cells in lung biopsy tissue.1 In another account, human herpesvirus 6B, implicated through polymerase chain reaction testing of tracheal secretions and lung biopsy specimens, was the source of fatal viral pneumonitis in an immunocompetent patient.2 Although human herpesvirus 6B pneumonia is believed to be highly unusual in immunocompetent hosts, its incidence may be underestimated, because clinicians do not routinely include the virus in the investigation panel for viral pneumonitis.

Our patient's contact history and skin rash were clinically more compatible with primary infection than endogenous reactivation. Furthermore, the absence of detectable human herpesvirus 6B DNA in his serum reflected the transient viremic phase typical of primary acute infection.3 Endogenous reactivation, on the other hand, is characterized by persistent viremia, because latent human herpesvirus 6B is predominantly incorporated within circulating CD4+ lymphocytes. Finally, the positive nasopharyngeal aspirate and the negative serum specimen definitively excluded chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6B, an inherited condition that is generally associated with very high viral loads in the circulation.4

Polymerase chain reaction's utility in analyzing nasopharyngeal aspirates of patients with suspected human herpesvirus 6B pneumonia is underscored by our experience. Asymptomatic shedding of the virus in saliva, a well-documented occurrence, limits the value of polymerase chain reaction testing of expectorated sputum specimens and even bronchoscopic lavage samples, which might contain oral secretions.5 Although shedding of human herpesvirus 6 in nasopharyngeal aspirate has not been rigorously studied in healthy individuals, we simultaneously performed polymerase chain reaction testing on 100 nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens from adults, and all were negative for human herpesvirus 6 DNA (data not shown), suggesting that asymptomatic shedding is not a common phenomenon.

On rare occasions, primary human herpesvirus 6 infection in adults can cause complications and possibly fatal outcomes.6 Moreover, it is an emerging pathogen in immunocompromised patients; viral reactivation has been associated with interstitial pneumonitis, encephalitis, acute graft-versus-host disease, and mortality.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Although childhood infection can be ubiquitous in many areas, adult seroprevalence rates vary widely among different populations (range, 20%-100%).10 Therefore, a variable proportion of adults are susceptible to infection in later life.

Management

Our patient was empirically treated with intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanate and oral azithromycin for 3 days. Antibiotics were then discontinued because a viral cause for his pneumonia was considered more likely. His fever subsided, and the rash and cough gradually improved. He was discharged after 4 days and was well at a 1-month follow-up visit.

Conclusions

Drugs proven to be clinically effective against human herpesvirus 6 are still lacking. The relatively toxic antivirals, ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir, have been used to treat human herpesvirus 6 disease or reactivation. However, drug toxicity and reduced drug susceptibility are a problem and pose management difficulties, especially in immunocompromised patients. The antimalarial agent artesunate was reported to have in vitro efficacy against human herpesvirus 6 and the closely related cytomegalovirus, and it was successfully used to treat a patient with human herpesvirus 6B myocarditis.12, 13 When constructing a differential diagnosis, physicians should be aware that human herpesvirus 6B is a potential culprit in atypical pneumonia in adults. The virus may be overlooked in populations with low seroprevalence.

Thomas J. Marrie, MD, Section Editor

Footnotes

Funding: This work is partly supported by the consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Disease for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Department of Health.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Authorship: All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing this manuscript.

The study was approved by the Institute Review Board, The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (reference UW-04-278 T/600).

References

- 1.Russler S.K., Tapper M.A., Knox K.K., Liepins A., Carrigan D.R. Pneumonitis associated with coinfection by human herpesvirus 6 and Legionella in an immunocompetent adult. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1405–1411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merk J., Schmid F.X., Fleck M. Fatal pulmonary failure attributable to viral pneumonia with human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) in a young immunocompetent woman. J Intensive Care Med. 2005;20:302–306. doi: 10.1177/0885066605279068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward K.N. The natural history and laboratory diagnosis of human herpesviruses-6 and -7 infections in the immunocompetent. J Clin Virol. 2005;32:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward K.N., Leong H.N., Nacheva E.P. Human herpesvirus 6 chromosomal integration in immunocompetent patients results in high levels of viral DNA in blood, sera, and hair follicles. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1571–1574. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1571-1574.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy J.A., Ferro F., Greenspan D., Lennette E.T. Frequent isolation of HHV-6 from saliva and high seroprevalence of the virus in the population. Lancet. 1990;335:1047–1050. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92628-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akashi K., Eizuru Y., Sumiyoshi Y. Brief report: severe infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome and primary human herpesvirus 6 infection in an adult. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:168–171. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307153290304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamoto S., Hatanaka K., Imakita M., Tamaki T. Central diabetes insipidus in an HHV6 encephalitis patient with a posterior pituitary lesion that developed after tandem cord blood transplantation. Intern Med. 2013;52:1107–1110. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.9432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mariotte E., Schnell D., Scieux C. Significance of herpesvirus 6 in BAL fluid of hematology patients with acute respiratory failure. Infection. 2011;39:225–230. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Pagter P.J., Schuurman R., Keukens L. Human herpes virus 6 reactivation: important predictor for poor outcome after myeloablative, but not nonmyeloablative allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:1460–1464. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun D.K., Dominguez G., Pellett P.E. Human herpesvirus 6. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:521–567. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agut H. Deciphering the clinical impact of acute human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infections. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakacova N., Klingel K., Kandolf R., Engdahl E., Fogdell-Hahn A., Higgins T. First therapeutic use of Artesunate in treatment of human herpesvirus 6B myocarditis in a child. J Clin Virol. 2013;57:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milbradt J., Auerochs S., Korn K., Marschall M. Sensitivity of human herpesvirus 6 and other human herpesviruses to the broad-spectrum antiinfective drug artesunate. J Clin Virol. 2009;46:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]