Abstract

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and elderly individuals are prone to the development of significant lower respiratory tract symptoms from colds caused by viral respiratory pathogens. Longitudinal surveillance studies conducted to assess the impact of viral respiratory tract pathogens on morbidity and mortality in each of these at-risk populations demonstrate that there is a substantial burden of disease from viral respiratory infection (VRI), including rhinovirus infections, with respect to utilization of health-care resources. Despite a similar rate of occurrence of VRI among subjects with COPD and the control group, a cohort with moderate to severe COPD had a 2-fold increase in medical resource utilization, including clinician visits, emergency center visits, and hospitalizations. In surveillance studies of respiratory viruses in the elderly, regular seasonal infections with rhinoviruses cause substantial morbidity, which has been largely underappreciated and underreported.

The population in the United States is aging, and it is predicted that by the year 2030, an estimated 68 million to 70 million US citizens will be 65 years of age or older. As individuals age, there is an increase in morbidity and mortality associated with many medical conditions, which often results in increased utilization of medical resources.1

The contributions of viral respiratory infections (VRIs) to morbidity in elderly people and those with underlying pulmonary disease have not been widely described or appreciated. With respect to utilization of medical services, the burden of disease from VRIs is substantial in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and in the elderly. In a longitudinal study of people aged 60 and older with rhinovirus infections, nearly 67% developed lower respiratory tract illness.2 Similar rates have been documented in patients with chronic lung disease.3

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

COPD is a pathologic medical condition that affects an estimated 16 million people and is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States.4 The prevalence of COPD is expected to increase as the population ages. COPD is characterized by nonreversible, progressive airflow limitation, including obstructive bronchitis, emphysema, mucus plugging, loss of lung elasticity, and closure of small airways.5

Patients with COPD use medical resources that total more than $24 billion per year.6 Acute exacerbations of COPD are a frequent cause of hospital admission, and subsequent illnesses from exacerbations of COPD are often prolonged and have a profound impact on quality of life and morbidity.3, 5 Deaths per 100,000 from COPD have quadrupled in the past 50 years in the United States, whereas age-adjusted death rates from all causes have decreased.7

Although the viruses that cause acute respiratory illness in patients with COPD are similar to those recovered from otherwise healthy adults, studies suggest that patients with COPD have increased illness rates and/or may be more susceptible to illness caused by specific viruses.6 Deterioration in pulmonary function from exacerbations of COPD may be due to 1 or more viral, bacterial, or mixed viral-bacterial pathogens in the respiratory tract. Patients with COPD recover more slowly than those without COPD. The reasons for this are not entirely clear. Some have speculated that recovery may be slowed because of unexplained pathophysiologic mechanisms that include mucosal damage from the disease, deterioration in lung function, or release of histamine or other inflammatory mediators.3 A recent study by Seemungal et al8 has reported higher IL-6 levels in patients with COPD with exacerbations and a slower clinical recovery in virus-proven infections.

VRI in adults with COPD

The role of VRI in elderly adults with and without COPD was evaluated in a longitudinal cohort study conducted from September 1991 to April 1994 that defined cause, frequency, severity of illness, and utilization of medical care services.6

For this study, 117 patients were enrolled and fully evaluable.6 Pulmonary function in all subjects was assessed at baseline by spirometry and used to stratify subjects into control (subjects who had no history of COPD) and COPD groups: 30 subjects with mild COPD and 32 with moderate to severe COPD. All patients were recruited through local private physicians and hospital pulmonary clinics and a hospital registry of older persons. Control subjects had baseline forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) greater than 80% of predicted. The group with mild COPD had baseline FEV1 50% or greater and less than 80% of predicted. The group with moderate to severe COPD had baseline FEV1 less than 50% of predicted. Approximately 90% of the study subjects received vaccinations for influenza (range, 89.2% to 93.9%). Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. 6

Table 1.

Demographics and Enrollment Pulmonary Function Test Results for Control and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Groups

| Characteristic | Control Subjects∗ | COPD Subjects |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mild Obstruction† | Moderate/Severe Obstruction† | ||

| n | 55 | 62 | 30 | 32 |

| Baseline FEV1 (mean ± SD) | 2.49 ± 0.59 | 1.28 ± 0.57 | 1.70 ± 0.45 | 0.89 ± 0.34 |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 67.5 ± 5.3 | 65.4 ± 7.4 | 67.1 ± 6.0 | 63.8 ± 8.3 |

| Sex (M/F) | 24/31 | 26/36 | 13/17 | 13/19 |

| Months of follow-up (mean ± SD) | 35.1 ± 10.9‡ | 26.3 ± 14.2‡ | 28.1 ± 11.7 | 24.6 ± 13.2 |

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Adapted from Am J Respir Crit Care Med.6

FEV1 at baseline >80% of predicted.

Baseline pulmonary function tests included spirometry; mild obstruction was defined as an enrollment FEV1 ≥50% and <80% predicted, and moderate/severe obstruction was defined as an enrollment FEV1 <50% predicted.

P <0.001.

More subjects in the COPD group discontinued the study prematurely (29 of 62), compared with the controls (10 of 55; P <0.002). Significantly more subjects in the control group (89%) than in the COPD group (64%) were followed for 2 or more winter seasons (P <0.002). Three subjects in the COPD group were followed for less than 1 complete fall/winter season. Early study termination was similar in the 2 groups. Subject request was the most common reason for discontinuation, followed by death of the subject, a residential move out of the state, or a loss to follow-up.6

Picornaviruses were the most common viral pathogens identified in the study, followed by parainfluenza viruses and coronaviruses. Seventy-five percent of the picornaviruses were identified as rhinoviruses. Rhinoviruses and coronaviruses were the cause of 35% of the virus infections experienced by the control group, and they accounted for 43% of the virus infections in the group with COPD. There were no statistically significant differences in frequency of virus isolation between the COPD and control subjects (Table 2). 6

Table 2.

Etiology of Documented Viral Respiratory Infections

| Respiratory Virus | Control Subjects | COPD Subjects |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mild Obstruction | Moderate/Severe Obstruction | ||

| Picornavirus | 28 | 16 | 8 | 8 |

| Parainfluenza virus | 23 | 20 | 9 | 11 |

| Coronavirus OC43/229E | 12 | 16 | 6 | 10 |

| Influenza virus A/B | 15 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 9 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| Adenovirus | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 91 | 70 | 31 | 39 |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Reprinted with permission from Am J Respir Crit Care Med.6

Acute respiratory illness occurred more frequently among subjects with moderate to severe COPD (3.0 acute respiratory illnesses per year), compared with those who had mild COPD (1.8 acute respiratory illnesses per year) or with controls (1.3 acute respiratory illnesses per year; P <0.001). The annual rate of virus-proven respiratory illnesses was not significantly different between the control subjects (0.54 illnesses per year) and the subjects with COPD (0.45 illnesses per year). Identification and frequency of viruses by symptoms and clinical syndrome were assessed for upper and lower respiratory tract illness. The cause of documented virus infection was more common for upper respiratory tract illnesses (URTIs) than lower respiratory tract illnesses (LRTIs). URTIs included rhinitis, laryngitis, or pharyngitis. LRTI was defined as increased cough, shortness of breath, and changes in sputum production or color.6

Among control subjects with picornavirus, 92% had rhinitis, 75% had pharyngitis, and 38% had laryngitis. Clinical syndromes in subjects with COPD with confirmed picornavirus included the following URTIs: 77% rhinitis, 77% pharyngitis, and 38% laryngitis. Overall, control subjects presented with higher percentages of URTI than did the subjects with COPD (Table 3).6 Virus identification rates were similar for control subjects and subjects with COPD with signs and symptoms of URTI (35% for control subjects and 37.5% for subjects with COPD).

Table 3.

Virus-Associated Illness With Upper Respiratory Tract Infection Symptomatology in Control and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Groups

| Control Subjects | COPD Subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical syndrome | ||

| Rhinitis | 75/185 (40%) | 43/181 (24%) |

| Pharyngitis | 62/159 (39%) | 35/113 (31%) |

| Laryngitis | 35/69 (51%) | 15/47 (32%) |

| Clinical syndrome with picornavirus infection | ||

| Rhinitis | 22/24 (92%) | 10/13 (77%) |

| Pharyngitis | 18/24 (75%) | 10/13 (77%) |

| Laryngitis | 9/24 (38%) | 5/13 (38%) |

Data from Greenberg et al, unpublished results.

In symptomatic subjects with mixed URTIs and LRTIs, viruses were identified in 39% of the control subjects and in 19% of the COPD cohort (P <0.001). In a recent similar study using PCR techniques, respiratory viruses were identified in 44% of a group of patients with chronic bronchitis followed longitudinally for acute respiratory illness (Atmar RL, Bandi V, and Greenberg SB, unpublished observations). Picornaviruses accounted for 39% of all viral-proven illnesses.

A similar study in patients with COPD in London detected respiratory viruses in 39.2% of exacerbations.8 VRIs were detected in each month of the year, although the total number of respiratory illnesses in control subjects peaked during the winter months of December, January, and February. Illnesses in the COPD group occurred over a longer duration.

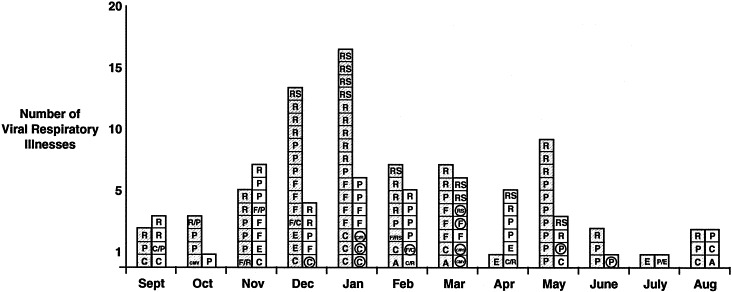

In the study by Greenberg et al6 comparing VRIs in adults with and without COPD, an increase started in September and remained elevated through May (Figure 1). The median duration of illness was 15 days for patients with COPD.6 Importantly, even though influenza virus circulated in the community during the evaluation period, the majority of virus-associated illnesses in both the heavily vaccinated control and COPD groups were not the result of influenza virus.

Figure 1.

Seasonal variation of viral respiratory infections by month. Hatched squares = controls; open squares = COPD; A = adenovirus; C = coronavirus; CMV = cytomegalovirus; E = enterovirus; F = influenza virus A or B; P = parainfluenza virus type 1, 2, or 3; R = rhinovirus; RS = respiratory syncytial virus. Dual viral infections are designated with backslash (/). Circles signify hospitalizations. (Reprinted with permission from Am J Respir Crit Care Med.6)

Although influenza immunization did not completely prevent infection and illness, others have demonstrated a decrease in severe complications and hospitalizations in immunized adults. Coronavirus infection was most frequently identified in hospitalized patients. Only 20% (2 of 10) of hospitalizations among the study groups were the result of influenza.6

Subjects with moderate to severe COPD accessed medical care more frequently than controls or subjects with mild COPD. Fifty-eight percent of the total COPD cohort and 31% of control subjects had at least 1 office visit for their VRI (P <0.001). Six percent of the total COPD cohort were seen in emergency centers (12% of subjects with moderate to severe COPD), and 19% were hospitalized (35% of subjects with moderate to severe COPD). No control subjects required emergency care or hospitalization.6

Despite a similar rate of occurrence of VRI among subjects with COPD and the control group, the cohort with moderate to severe COPD had a 2-fold increase in medical resource utilization, including clinician visits, emergency center visits, and hospitalizations.6

VRI in the elderly

A large 2-year community-based surveillance study was performed by Nicholson et al to assess the role of rhinoviruses in a cohort of 533 ambulatory subjects aged 60 and older, and another study assessed the medical burden of disease.9 Viral sources of infection were identified in 43% (231 pathogens identified for 211 of 497 episodes) of the documented respiratory illnesses. Of the 231 pathogens identified in upper respiratory episodes, rhinovirus was the most prevalent pathogen (121 isolates; 53%). Fifty-nine coronaviruses were identified (26%), followed by 22 influenza viruses (9.5%), and 17 isolates of respiratory syncytial virus (7.4%; Table 4).9 Dual virus infections were observed in 10% to 15% of the isolates.9 Rhinoviruses were the most common type of virus found in isolates with dual infections. The median duration of illness was 16 days. Duration of illness was longer for elderly persons with lower respiratory tract symptoms (16 days vs 12 days).9

Table 4.

Pathogens Identified During 211 of the 497 Upper Respiratory Episodes for Which Laboratory Specimens Were Available

| Pathogen | Single Infections | Coinfections | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhinovirus | 107 | 14 | 121 |

| Coronavirus | 45 | 14 | 59 |

| Influenza A and B | 19 | 3 | 22 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 11 | 6 | 17 |

| Parainfluenza | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Chlamydia spp. | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Adenovirus | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 193 | 38 | 231 |

Adapted from BMJ.9

Ninety-eight percent of the subjects described upper respiratory tract symptoms, 65% had lower respiratory tract symptoms, and 58% had systemic symptoms. There were no distinguishing symptoms or characteristics that differentiated one type of viral infection from another. Age, sex, and smoking status of the infected subjects were comparable, regardless of which virus was identified.9

Activities were restricted in 20% of those with rhinovirus infection. Hospitalization was uncommon, and medical care was sought by subjects only approximately 48 hours after initiation of symptoms; 41 (43%) of the rhinovirus-infected subjects sought medical care. Antimicrobials were prescribed empirically in 31 of the 41 medical consultations (76%), primarily for suspected LRTIs.

Nicholson et al2 used regression analysis to identify those at increased risk of lower respiratory tract disease, because so little is known about the risk factors and immunopathologic or pathophysiologic mechanisms that trigger lower respiratory episodes. Rhinoviruses were associated with lower respiratory tract illnesses more often in elderly subjects who were current smokers, had chronic lung disease, or had other underlying medical conditions.2

In these elderly subjects, rhinoviruses were responsible for a greater disease burden than that of influenza, with disease burden defined as restriction of activities and greater frequency and duration of illness.9 The burden-of-disease measurement used for comparison was a method developed by the US Institute of Medicine’s committee on issues and priorities in new vaccine development for diseases of importance in the United States. These investigators concluded that morbidity and mortality from seasonal infections of rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus have been underestimated and are overshadowed by more readily recognizable epidemics of influenza.

VRIs among the elderly have also been well documented in the institutional setting. Wald et al10 described a passive surveillance study of a large rhinovirus outbreak among institutionalized elderly residents in a long-term-care facility. Overall, illness varied in severity, but serious lower respiratory tract involvement was apparent in several persons with COPD. New onset of lower respiratory tract symptoms was documented in 50% of the infected persons and was attributed to rhinovirus infection.

Conclusions

Picornaviruses, and more specifically the rhinoviruses, are important viral respiratory tract pathogens that cause increased exacerbations and morbidity in patients with COPD and in the elderly. Rhinoviruses have been implicated in VRIs in the ambulatory elderly as well as those in long-term-care facilities. Rhinoviruses are associated with a higher incidence of lower respiratory illness in the elderly, which accounts for higher numbers of clinician visits, activity restrictions, and a significant number of antibiotic prescriptions for this patient population. Hospitalizations for VRIs resulting from rhinovirus may be increased among subjects with moderate to severe COPD. With the increased prevalence of vulnerable, high-risk patients with COPD and the growing population of elderly in society, newer antiviral agents are needed for prophylaxis against common viral respiratory tract infections.

References

- 1.Weinstein R.A. Practice guidelines make perfect, part IV: recognizing infections and fever in the institutionalized elderly. Conference summary from the 38th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Disease Society of America.; 2001. Accessed May 3, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson K.G, Kent J, Hammersley V, Cancio E. Risk factors for lower respiratory complications of rhinovirus infections in elderly people living in the community: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1996;313:1119–1123. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7065.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiselka M.J, Kent J, Cookson J.B, Nicholson K.G. Impact of respiratory virus infection in patients with chronic chest disease. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:337–346. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.April 4, 2001. International guidelines released on chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD): fourth leading cause of death in US and worldwide.www.nhlbi.nih.gov/new/press/01-04-04.htm NIH news release. Accessed July 4, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes P.J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:269–280. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg S.B, Allen M, Wilson J, Atmar R.L. Respiratory viral infections in adults with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:167–173. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9911019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health Morbidity & Mortality Chartbook. Cardiovascular, Lung & Blood Diseases. 2000 http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htm Accessed October 2, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seemungal T, Harper-Owen R, Bhowemik A. Respiratory viruses, symptoms and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1618–1623. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2105011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicholson K.G, Kent J, Hammersley V, Cancio E. Acute viral infections of upper respiratory tract in elderly people living in the community: comparative, prospective population based study of disease burden. BMJ. 1997;315:1060–1064. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wald T.G, Shult P, Krause P, Miller B.A, Drinka P, Gravenstein S. A rhinovirus outbreak among residents of a long-term care facility. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:588–593. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-8-199510150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]