Policies and public health efforts have not addressed the gendered impacts of disease outbreaks.1 The response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears no different. We are not aware of any gender analysis of the outbreak by global health institutions or governments in affected countries or in preparedness phases. Recognising the extent to which disease outbreaks affect women and men differently is a fundamental step to understanding the primary and secondary effects of a health emergency on different individuals and communities, and for creating effective, equitable policies and interventions.

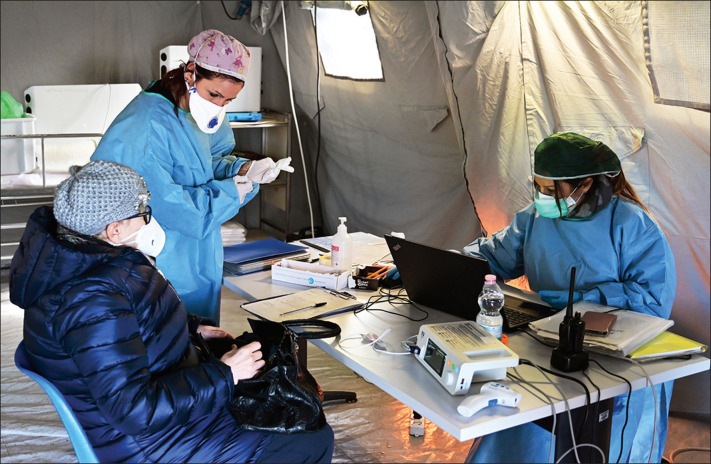

Although sex-disaggregated data for COVID-19 show equal numbers of cases between men and women so far, there seem to be sex differences in mortality and vulnerability to the disease.2 Emerging evidence suggests that more men than women are dying, potentially due to sex-based immunological3 or gendered differences, such as patterns and prevalence of smoking.4 However, current sex-disaggregated data are incomplete, cautioning against early assumptions. Simultaneously, data from the State Council Information Office in China suggest that more than 90% of health-care workers in Hubei province are women, emphasising the gendered nature of the health workforce and the risk that predominantly female health workers incur.5

The closure of schools to control COVID-19 transmission in China, Hong Kong, Italy, South Korea, and beyond might have a differential effect on women, who provide most of the informal care within families, with the consequence of limiting their work and economic opportunities. Travel restrictions cause financial challenges and uncertainty for mostly female foreign domestic workers, many of whom travel in southeast Asia between the Philippines, Indonesia, Hong Kong, and Singapore.6 Consideration is further needed of the gendered implications of quarantine, such as whether women and men's different physical, cultural, security, and sanitary needs are recognised.

Experience from past outbreaks shows the importance of incorporating a gender analysis into preparedness and response efforts to improve the effectiveness of health interventions and promote gender and health equity goals. During the 2014–16 west African outbreak of Ebola virus disease, gendered norms meant that women were more likely to be infected by the virus, given their predominant roles as caregivers within families and as front-line health-care workers.7 Women were less likely than men to have power in decision making around the outbreak, and their needs were largely unmet.8 For example, resources for reproductive and sexual health were diverted to the emergency response, contributing to a rise in maternal mortality in a region with one of the highest rates in the world.9 During the Zika virus outbreak, differences in power between men and women meant that women did not have autonomy over their sexual and reproductive lives,10 which was compounded by their inadequate access to health care and insufficient financial resources to travel to hospitals for check-ups for their children, despite women doing most of the community vector control activities.11

Given their front-line interaction with communities, it is concerning that women have not been fully incorporated into global health security surveillance, detection, and prevention mechanisms. Women's socially prescribed care roles typically place them in a prime position to identify trends at the local level that might signal the start of an outbreak and thus improve global health security. Although women should not be further burdened, particularly considering much of their labour during health crises goes underpaid or unpaid, incorporating women's voices and knowledge could be empowering and improve outbreak preparedness and response. Despite the WHO Executive Board recognising the need to include women in decision making for outbreak preparedness and response,12 there is inadequate women's representation in national and global COVID-19 policy spaces, such as in the White House Coronavirus Task Force.13

© 2020 Miguel Medina/Contributor/Getty Images

If the response to disease outbreaks such as COVID-19 is to be effective and not reproduce or perpetuate gender and health inequities, it is important that gender norms, roles, and relations that influence women's and men's differential vulnerability to infection, exposure to pathogens, and treatment received, as well as how these may differ among different groups of women and men, are considered and addressed. We call on governments and global health institutions to consider the sex and gender effects of the COVID-19 outbreak, both direct and indirect, and conduct an analysis of the gendered impacts of the multiple outbreaks, incorporating the voices of women on the front line of the response to COVID-19 and of those most affected by the disease within preparedness and response policies or practices going forward.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Smith J. Overcoming the “tyranny of the urgent”: integrating gender into disease outbreak preparedness and response. Gender Develop. 2019;27:355–369. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVD-19) China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Zhang M, Yang L, et al. Prevalence and patterns of tobacco smoking among Chinese adult men and women: findings of the 2010 national smoking survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71:154–161. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-207805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boniol M, McIsaac M, Xu L, Wuliji T, Diallo K, Campbell J. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2019. Gender equity in the health workforce: analysis of 104 countries: Working Paper 1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho R, Cheung E, Siu P. Coronavirus: Hong Kong families await return of thousands of stranded domestic helpers as the Philippines lifts travel ban. South China Morning Post. Feb 18, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies SE, Bennett B. A gendered human rights analysis of Ebola and Zika: locating gender in global health emergencies. Int Aff. 2016;92:1041–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harman S. Ebola, gender and conspicuously invisible women in global health governance. Third World Quart. 2016;37:524–541. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sochas L, Channon AA, Nam S. Counting indirect crisis-related deaths in the context of a low-resilience health system: the case of maternal and neonatal health during the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(suppl 3):iii32–iii39. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wenham C, Arevalo A, Coast E, et al. Zika, abortion and health emergencies: a review of contemporary debates. Global Health. 2019;15:49. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0489-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenham C, Nunes J, Correa Matta G, de Oliveira Nogueira C, Aparecida Valente P, Pimenta DN. Gender mainstreaming as a pathway for sustainable arbovirus control in Latin America. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Executive Board EB146/Conf/17: strengthening preparedness for health emergencies; implementation of International Health Regulations, IHR (2005) [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Economic Times Indian-American Seema Verma appointed as key member of US COVID-19 Task Force. The Economic Times. March 3, 2020 [Google Scholar]