Abstract

Objective

We investigated the prevalence of childhood adversity among healthcare workers and if such experiences affect responses to adult life stress.

Methods

A secondary analysis was conducted of a 2003 study of 176 hospital-based healthcare workers, which surveyed lifetime traumatic events, recent life events, psychological distress, coping, social support, and days off work due to stress or illness.

Results

Sixty eight percent (95% CI 61.1–74.9) of healthcare workers had one or more experience of violence, abuse or neglect, 33% (95% CI 26.1–40.0) before the age of 13. Compared to healthcare workers who did not experience childhood adversity, those who did reported more recent life events (median 11 vs. 5 over the previous 6 months, p < .001) and greater psychological distress (median score 17 vs. 13, p < .001). The relationship between life events and psychological distress was not linear. Most healthcare workers without childhood adversity (73%) reported a low number of life events which were not associated with psychological distress. Most healthcare workers with childhood adversity (81%) reported a higher number of life events, for which the correlation between events and distress was moderately strong (Spearman's rho = .50, p < .001). Childhood adversity was also associated with more missed work days. Each of these outcomes was higher in 22 healthcare workers (13%) who had experienced more than one type of childhood adversity.

Conclusions

Childhood adversity is common among healthcare workers and is associated with a greater number of life events, more psychological distress and impairment.

Keywords: Stress, Abuse, Neglect, Healthcare workers

Introduction

Healthcare workers face many stressors that are specific to their profession, such as a perceived imbalance between effort and reward (Kluska et al., 2004, McGillis-Hall and Kiesners, 2005, Weyers et al., 2006) exposure to workplace violence (Duncan et al., 2001, Fernandes et al., 1999), the burden of patients’ emotional needs and suffering, and the personal impact of the constraints that the healthcare system imposes on care (McGillis-Hall and Kiesners, 2005, Spence-Laschinger et al., 2001). The high prevalence of professional burnout (Aiken et al., 2002a, Embriaco et al., 2007) indicates that long-term stress takes a toll. In addition to the cost to individuals, the conditions that contribute to stress may also make recruitment and retention of professionals more difficult and may affect patient outcomes (Aiken et al., 2002a, Aiken et al., 2002b, Gunnarsdottir et al., 2009). Although workplace characteristics that influence stress have been identified (Aiken et al., 2002b, Kivimaki et al., 2004, Spence-Laschinger et al., 2001) less is known about individual differences between healthcare workers which contribute to the impact of stress. Identifying the determinants of healthcare workers’ resilience or vulnerability to life stress may lead to better individual health, and in turn enhance patient-provider interaction and quality of care.

The purpose of this study is to investigate individual group differences in stress response and psychological distress among hospital workers. In particular, the purpose is to determine (i) the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in hospital workers, and (ii) if the experience of childhood adversity affects how healthcare workers respond to contemporary stressors. We expected that childhood exposure to trauma or adversity would result in vulnerability to stressful events later in life. Thus, based on a diathesis-stress model, it was hypothesized that healthcare workers who had experienced trauma or adversity as children would experience two adult outcomes that demonstrate vulnerability to stress: (i) a steeper slope of the correlation between adult life events and subsequent psychological distress; and (ii) more days off work due to stress or illness. Because it has been reported that exposure to multiple types of childhood trauma is highly predictive of symptom outcomes (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007) we also investigated the impact of experiencing more than one type of trauma.

In order to measure the prevalence of childhood trauma in healthcare workers and to test its impact on stress response, we performed a secondary analysis on data that were originally collected to determine the psychological impact of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak on hospital workers (Lancee et al., 2008, Maunder et al., 2006). The Impact of SARS Study took place in Canadian hospitals 13 to 23 months after the 2003 outbreak of SARS. It included several variables that are relevant to the purpose of the current study, including measures of lifetime experience with trauma, life events over the 6-month period before the study and measures of subjective distress and occupational impairment. The study also measured ways of coping, social support and subjective response to stressful events, which are possible mediators or moderators of stress response that could also be affected by childhood adversity.

It is important to emphasize the special characteristics of the people who participated in this study. Much research on the effects of childhood adversity has been conducted on clinical populations or in the community. The healthcare workers in this study, on the other hand, are neither selected for having health problems, nor are they necessarily representative of community norms. On the contrary, it is possible that these individuals are self-selected for resilience to stress, since they are all working, have persisted in healthcare work for many years (a median 20 years of healthcare experience) and have continued to work in their field 1–2 years after their SARS experience.

There have been few studies of the prevalence of childhood abuse and adversity in healthcare workers (deLahunta and Tulsky, 1996, Diaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2001, Gallop et al., 1995). In considering whether healthcare workers are representative of their communities with respect to their exposure to childhood adversity, at least two career-selection biases should be considered. First, it is possible that there is a force of selection in healthcare careers. Healthcare professionals have successfully navigated “filters” of personal vulnerability in order to complete post-secondary education and maintain a career in a stressful workplace. Since severe childhood adversity is associated with a number of consequences that could disadvantage a person in these challenges (Horwitz et al., 2001, Spataro et al., 2004) there may be a selective pressure that, if acting independently, would result in a lower prevalence of childhood adversity among healthcare workers than is found in the community. The second possibility is that the experience of early life adversity influences an individual to wish to work in the healing professions (Jackson, 2001). It is consistent with this idea that while childhood maltreatment generally increases risk for mental health problems, a substantial minority of maltreated individuals have no such problems as adults (Collishaw et al., 2007). Ten percent of nurses with a personal history of childhood sexual abuse have indicated that their abuse had at least a moderate impact on their decision to become a nurse (Gallop et al., 1995). The latter force, acting on its own, would result in an elevated prevalence of childhood adversity in healthcare workers relative to the community. These are not mutually exclusive possibilities; it could occur that both selective forces and an influence toward a career in healthcare both influence the career of a given individual, and that individuals might differ from one another with respect to the influence of childhood adversity on career choice. Finally, for some individuals, the experience of childhood adversity may be irrelevant to career choice.

The Impact of SARS Study database allows a more detailed examination of the link between childhood abuse or adversity and current distress in healthcare workers than has previously been reported. Although the Impact of SARS Study was designed to determine the psychological impact of an infectious outbreak, not to determine the prevalence and impact of childhood adversity on healthcare workers, in the absence of more definitive studies this data provides a useful window on this question, and allows for provisional hypothesis testing.

Methods

The Impact of SARS Study took place in Ontario, Canada between October 23, 2004 and September 30, 2005 in nine academic and community hospitals in Toronto and four in Hamilton. The Impact of SARS Study was designed to determine the psychological impact of an infectious outbreak on exposed hospital workers. Therefore, the population sampled included nurses in medical or surgical inpatient units and all staff of intensive care units, emergency departments and SARS isolation units. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Boards of each hospital.

All participants (n = 769) completed several self-administered instruments. Of these 769 participants, 179 (23.3%) were willing to complete a second survey, which included a self-administered survey of traumatic experiences. The second survey was completed a median of 9 weeks after the first survey (interquartile range 7–14 weeks). Because all 769 participants completed a survey that included demographic data and measures of distress, burnout, posttraumatic symptoms and behavioral impact of SARS, there is extensive evidence that demonstrates that the subsample (n = 179) does not differ from the full sample (n = 769) on psychological measures (Lancee et al., 2008). Furthermore, we have previously reported on a comparison of the participants in the full sample to non-participant healthcare workers, which demonstrated that they do not differ with respect to in age, job type, years of healthcare experience, or overall subjective impact of SARS on their lives (Maunder et al., 2006).

Three subjects did not complete the trauma questionnaire and were excluded from the current analysis. Of 176 participants, 159 (90%) were women. Twenty-four (14%) were single, 132 (75%) married, and 20 (11%) separated or widowed. Most were nurses (n = 142, 81%) with the remaining divided between a number of clinical (n = 18, 10%) and non-clinical (n = 16, 9%) jobs. The mean age of participants was 45 years (SD 9.4) and the mean duration of work in healthcare was 20 years (SD 10.3).

Lifetime experience with adverse events and trauma was surveyed with the TSI Life Event Questionnaire (Miller, Veltkamp, Heister, & Shirley, 1998) a 19-item questionnaire that surveys exposure to a broad range of potentially traumatic events and the earliest age at which each exposure occurred. Recent life events were counted as the sum of events reported over the previous 6-month period using the Responses to Life Events Scale (Marziali & Pilkonis, 1986) modified to provide a checklist of 120 common life events in the areas of job, school, finances, personal relationships, family, health, losses, injury, violence, children and pregnancy, and other experiences. In this sample, the number of life events in the previous 6 months was non-parametrically distributed and skewed toward zero.

Current psychological distress was measured with the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. The 10-item scale (K10) has been found to discriminate between cases and non-cases of SCID-diagnosed DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses and to show consistent psychometric properties across sociodemographic subgroups (Kessler et al., 2002). In this sample, the K10 was non-parametrically distributed and skewed toward the minimum score of 10. The reliability of the K10 (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.92.

Perceived social support was measured with the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, which was developed based on the responses of 2987 patients to the Medical Outcomes Study. Nineteen items measure the perceived availability of others to provide functional support if needed. The sum of these items correlates with measures of loneliness and family dysfunction and is distinct from measures of mental and physical health (Stewart et al., 1989). The survey also asks for the number of close friends and close relatives “you feel at ease with and can talk to about what is on your mind.” In the current study, perceived availability of support was non-parametrically distributed and skewed toward the maximum value. The reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of perceived availability of support was 0.97.

Coping responses were measured with reference to coping with the SARS experience using the Ways of Coping Inventory (Folkman and Lazarus, 1980, Folkman and Lazarus, 1988) a widely used instrument which yields eight subscales of coping strategies. The eight factor model has been supported in clinical and non-clinical samples (Lundqvist & Ahlstrom, 2006) and the reliability of the subscales across many studies has been adequate (typically 0.60 to 0.75) (Rexrode, Petersen, & O’Toole, 2008). Relative coping subscales (raw subscale score divided by total Ways of Coping score) were calculated for each of eight subscales. Relative scores remove the confounding influence of the intensity of distress experienced following SARS from the analysis of the types of coping which were used. In the current study, internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha) for coping subscales was problem-solving 0.73, seeking support 0.73, positive-reappraisal 0.77, distancing 0.68, confrontive coping 0.68, escape-avoidance 0.74, self-control 0.66, and taking responsibility 0.65. Coping through problem-solving, seeking support, positive reappraisal, confrontive coping, and self-control were normally distributed. Coping through escape-avoidance, accepting responsibility (self-blame), and distancing were non-parametrically distributed and skewed toward zero.

The number of work shifts missed due to stress or illness over 4 months, according to the participant's self-report, was used as a proxy of functional occupational impairment.

Analysis

Because we were interested in the impact of experiencing childhood violence, abuse and neglect on healthcare workers, we grouped the items of the TSI Life Event Questionnaire into those related to experiencing or observing violence, abuse and neglect (11 items) and those related to other types of exposure (7 items: experienced war, disaster, loss of a significant other, exposed to or experienced a life-threatening illness, felt responsible for another's death, heard about someone else's abuse). Multivariate ANOVA confirmed that the violence, abuse and neglect items were significantly associated with current psychological distress (F = 3.55, df = 11, p < .001) and that the items not related to the experience of violence, abuse and neglect were not associated with current psychological distress (F = .64, df = 7, p = .72). The latter were not included in subsequent analyses. The nonspecific item “other” was also excluded.

The prevalence (mean and 95% confidence interval) of each category of traumatic experience was calculated for each item during two periods: lifetime and at age 12 or younger. Items which could occur at any age (e.g., “experienced emotional abuse”) were assumed to occur at age 13 or older if the earliest age of occurrence was not reported. The item “experienced domestic violence, physical abuse, or neglect as a child” was grouped with events occurring at age 12 or younger if no age was provided.

Polyvictimization has been defined as the experience of 4 or more categories of childhood adversity (Finkelhor et al., 2007). In our sample, the occurrence of 4 or more categories of adversity before age 13 occurred in only 6 subjects (3.4%) and so to explore the impact of experiencing multiple types of adversity we categorized into subjects into 3 groups: no childhood violence abuse or neglect, 1 such event, more than 1 such event. The impact of multiple types of childhood trauma exposure on distress and on life events was tested by Kruskal-Wallis test.

Differences between participants with or without childhood adversity with respect to current distress, coping, social support, subjective response to stress and recent life events were tested by Student's t-test or by Mann-Whitney U-test. Univariate relationships between current distress and potential covariates of its association with childhood abuse (age, gender, ways of coping, and social support) were tested with parametric and nonparametric tests as appropriate.

We planned to test the hypothesis that the slope of the correlation between recent life events and psychological distress is steeper in healthcare workers with childhood adversity using regression analyses (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). However, the curve of the relationship between life events and psychological distress was nonlinear, with a slope significantly >0 present only at higher number of life events. The univariate relationship between life events and psychological distress did not differ between groups along this steeper portion of the curve (comparing the between-groups difference in Spearman's rank-order correlations using Fisher's z-transformation), which precluded further testing by regression analysis.

We tested the hypothesis that childhood history of adversity would be associated with functional impairment by comparing the days of work over the previous 4 months due to stress or illness (as reported by participants) in the healthcare workers with or without childhood adversity using a Chi-square test.

Central tendencies of parametrically distributed variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation and of non-parametrically distributed variables as median and inter-quartile range. Statistical significance was set at p < .05 (two-tailed). Statistical tests were performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago).

Results

Prevalence of violence, abuse or neglect

Over their lifetime, 120 healthcare workers (68%, 95% CI 61.1–74.9) had one or more experience of violence, abuse or neglect. The first experience of violence, abuse or neglect occurred before age 13 in 58 healthcare workers (33%, 26.1–40.0) (Table 1 ). Observing or experiencing sexual violence, sexual abuse or rape was reported by 28% (22.3–35.5) of healthcare workers, with 9% (5.7–14.3) reporting that these experiences occurred before age 13. Sexual contact before age 18 with someone who was at least 5 years older (whether a family member or not) was reported by 22% (16.2–28.3) of all participants and 21% (15.7–28.4) of female participants.

Table 1.

Prevalence of experiences of violence, abuse or neglect in healthcare workers.

| Lifetime |

Age 12 or younger |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | (95% CI) | n | % | (95% CI) | |

| Observed domestic violence, neglect, abuse | 58 | 33.0 | (26.5–40.2) | 22 | 12.5 | (8.0–18.0) |

| Observed emotional abuse of significant other | 57 | 32.4 | (25.6–39.2) | 17 | 9.7 | (5.6–14.4) |

| Experienced domestic violence, physical abuse or neglect as a child | 38 | 21.6 | (16.2–30.5) | 38 | 21.6 | (16.2–30.5) |

| Experienced domestic violence, physical abuse or neglect as an adult | 32 | 18.2 | (13.2–24.6) | |||

| Experienced emotional abuse | 78 | 44.3 | (37.2–51.7) | 11 | 6.2 | (2.5–9.5) |

| Observed sexual abuse or rape | 17 | 9.7 | (6.2–15.0) | 4 | 2.3 | (0.0–4.1) |

| Sexual contact with a family member at least 5 years older before the age of 18 | 18 | 10.2 | (6.5–15.6) | 10 | 5.7 | (2.5–9.5) |

| Sexual contact with a non-family member at least 5 years older before the age of 18 | 31 | 17.6 | (12.7–23.9) | 6 | 3.4 | (0.7–6.1) |

| Observed criminal violence, not rape | 20 | 11.4 | (7.5–16.9) | 4 | 2.3 | (0.0–4.1) |

| Experienced criminal violence, not rape | 26 | 14.8 | (10.3–20.8) | 4 | 2.3 | (0.0–4.1) |

| Experienced rape or sexual assault after age 18 | 18 | 10.2 | (6.5–15.6) | |||

| At least one of these | 120 | 68.2 | (61.1–74.9) | 58 | 33.0 | (26.1–40.0) |

The relationship of childhood adversity to coping, social support and subjective response to stress

None of the eight subscales of the Ways of Coping inventory (with the stressful event designated as SARS) differed between healthcare workers who had or had not experienced childhood adversity (all p > .10, values not shown). The perceived availability of support was lower in those who had experienced childhood adversity (median = 77, inter-quartile range = 63–90) than in those who had not experienced childhood adversity (median = 83, inter-quartile range = 73–92, p = .02). The total number of people available to provide support did not differ between healthcare workers who had experienced childhood adversity (median = 6, inter-quartile range = 4–10) compared to those without this experience (median = 7, inter-quartile range = 5–10, p = .29).

Participants were asked to provide a more detailed description of the one stressful event that they considered the most important in the last 6 months. Healthcare workers who had experienced childhood violence, abuse or neglect were significantly more likely to report that they responded to the recent event with feelings of anxiety or fear, discouragement or hopelessness, and by feeling overwhelmed or helpless (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Subjective response to the most stressful event of the previous six months, in healthcare workers with or without a history of childhood adversity.

| Violence, abuse or neglect before age 13 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 58) % |

No (n = 118) % |

Significance* | |

| Qualities of the stressful event | |||

| I had no control over the events that caused it | 43.1 | 47.5 | 0.57 |

| I was at least partially responsible | 27.6 | 16.9 | 0.10 |

| Someone else was at least partially responsible | 24.1 | 16.9 | 0.27 |

| Response to the stressful event | |||

| It made me feel sad | 50.0 | 40.7 | 0.24 |

| It made me feel frustrated or angry | 51.7 | 43.2 | 0.29 |

| It made me feel anxious, nervous or afraid | 43.1 | 27.1 | 0.03 |

| It made me feel discouraged or hopeless | 34.5 | 16.1 | 0.006 |

| It made me feel overwhelmed or helpless | 44.8 | 24.6 | 0.006 |

Significance of Chi-square, df = 1.

The relationship of childhood adversity to adult life events and psychological distress

The number of recent life events was higher in healthcare workers who had experienced childhood adversity (median 11, inter-quartile range 7–16) than in healthcare workers who had not (median 5, inter-quartile range 4–10, p < .001). Healthcare workers who experienced childhood adversity also reported higher levels of psychological distress (median 17, inter-quartile range 13–24) than those without childhood adversity (median 13, inter-quartile range 11–17, Mann-Whitney U = 2225, p < .001).

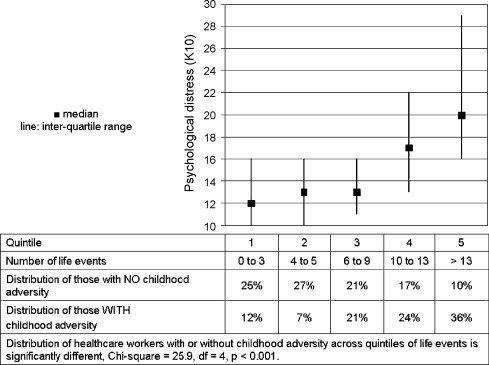

Figure 1 illustrates that the relationship between life events and distress is nonlinear. The relatively flat curve in the lower three quintiles of life events has a slope indistinguishable from zero (rho for quintiles 1 to 3 = .12, p = .21). The curve is steeper over the higher 3 quintiles (Spearman's rho = .44, p < .001). The slopes of these two portions of the curve are significantly different (z for Fisher's transformation = 2.53, p < .05). Furthermore, there are disproportionately more healthcare workers with a history of childhood adversity on the steep portion of the curve (Chi-square = 25.9, df = 4, p < .001). As is illustrated in Figure 1, 73% of healthcare workers without childhood adversity report recent life events in the bottom three quintiles, where the slope of the relationship between life events and distress is not significantly different from zero. On the other hand, 81% of healthcare workers who experienced childhood adversity report a number of life events that is on the steep portion of the curve, in the top three quintiles.

Figure 1.

The relationship between number of life events in previous 6 months and current psychological distress in healthcare workers with and without exposure to childhood adversity.

We tested if there was a difference in the slope of the correlation between life events and distress in the upper 3 quintiles of life events, where the relationship between life events and psychological distress is not flat. In this region of the curve, Spearman's rho in healthcare workers who have experienced childhood adversity is 0.50 (n = 47, p < .001) and in those without childhood adversity is 0.32 (n = 57, p = .02). These two correlations are not statistically different (z = 1.07, p > .05).

The relationship of childhood adversity to occupational impairment

Eighty-five healthcare workers (48%) reported that they had taken at least 1 day off work due to stress or sickness in the previous 4 months. Table 3 demonstrates that missed shifts were more common among healthcare workers with a history of childhood violence, abuse or neglect. Forty-one percent of healthcare workers exposed to childhood adversity reporting having missed 4 or more shifts in 4 months compared with 14% of workers with no such exposure.

Table 3.

Missed work shifts due to stress or illness in healthcare workers with or without exposure to childhood adversity.

| Shifts missed due to stress or illness in previous 4 months |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| None n (%) |

1 to 3 n (%) |

4 or more n (%) |

|

| Childhood adversity (n = 58) | 18 (31%) | 16 (28%) | 24 (41%) |

| No childhood adversity (n = 118) | 73 (62%) | 29 (25%) | 16 (14%) |

Significance of difference in distribution Chi-square = 20.5, df = 2, p < .001.

Exposure to multiple types of childhood adversity

Twenty-two healthcare workers (13%) reported 2 or more types of violence, abuse or neglect before the age of 13. Psychological distress rises along a gradient from healthcare workers with no such events (n = 114, median 13, inter-quartile range 11–17), to those with 1 type of adverse exposure (n = 36, median 17, inter-quartile range 12–21) or more than 1 type of childhood adversity (n = 22, median 19, inter-quartile range 14–28, Kruskal-Wallis H = 15.0, df = 2, p = .001).

The number of types of childhood trauma exposure is also significantly related to the number of recent life events reported (Kruskal-Wallis H = 22.8, df = 2, p < .001), with the median number of events reported being: no childhood adversity—5 events (inter-quartile range 4–10); 1 type of adversity—10 events (inter-quartile range 6–14); 2 or more types of adversity—15 events (inter-quartile range 8–23). The slope of the correlation between life events and psychological distress in healthcare workers with 2 or more types of childhood adversity was 0.64 (p < .001).

Multiple types of exposure were associated with greater occupational impairment measured by sick days (Kruskal-Wallis H = 21.8, df = 2, p < .001). The proportion of healthcare workers reporting 4 or more sick days in 4 months was 14% in those with no childhood violence, abuse or neglect, 33% in those with one type of adverse childhood exposure and 55% in those with two or more types of adverse childhood exposure.

Discussion

Among healthcare workers who participated in the Impact of SARS Study, the lifetime prevalence of trauma and adversity was 68%, with 33% reporting violence, abuse or neglect that first occurred at age 12 or younger. Although these numbers appear to be high, one must consider how this prevalence compares to rates of abuse and neglect in the community and in other groups of healthcare workers. After a discussion of the prevalence of childhood trauma, we will discuss how this exposure is related to the current state of these healthcare workers.

Most studies report the prevalence of particular types of adversity rather than taking a more global perspective (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005). As a result, comparing the current results to previous studies requires assessing different aspects of adversity separately and parsing the data to match the aspects of adversity measured in other studies as nearly as possible. We compare the prevalence of adversity in female healthcare workers to female community samples, because the confidence intervals on prevalence in male healthcare workers are large, due to small sample size.

With respect to childhood sexual abuse, in our study sexual contact before age 18 with someone who was at least 5 years older occurred in 21% of female participants (95% CI 16.0–28.0). For comparison, the Ontario Health Supplement (OHS) survey was an epidemiologic study of childhood sexual and physical abuse among 9953 stratified and randomly selected members of randomly selected households in the same Canadian province as the current study (MacMillan et al., 1997). As in our study, the OHS used a retrospective self-report questionnaire. Participants reported the occurrence of an adult exposing themselves, threatening to have sex, touching the sex parts of your body, or trying to have sex with you or sexually attacking you while you were growing up (with no age range specified). The 95% confidence intervals on the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse were 12.6–18.0% for women 25–44 years old at the time of the survey, and 10.0–17.6% for women 45–64 years old. Although the use of different questions precludes a precise comparison, the 2 studies have overlapping confidence intervals. The confidence intervals on the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in females in the current study also overlap with those in a major American epidemiologic study using a different question (Vogeltanz et al., 1999). Since the confidence intervals of the Impact of SARS Study overlap with those of both community samples, there is no evidence that prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in the Impact of SARS study is higher than the community.

With respect to childhood physical abuse, the OHS defined physical abuse with a list of specific events including being pushed or grabbed, having things thrown at you, being hit, kicked, burned, choked or physically attacked while you were growing up. The prevalence of physical abuse in females in the Ontario community was 21.1% (95% CI 19.3–22.9), very similar to the 19% (95% CI 13.6–25.7) of females in the Impact of SARS study who endorsed experiencing domestic violence, neglect or physical abuse as a child.

Emotional abuse was the most common form of adversity in the current study, at 44% (95% CI 37.2–51.7). The study of emotional abuse has been limited by difficulties with its definition. The Public Health Agency of Canada identifies several varieties of emotional abuse which occur in relationships of power and control (e.g., behavior that is rejecting, degrading, terrorizing, isolating, exploiting and unresponsive). They cite the findings of the 1995 Women's Health Test that 43% of women experienced emotional abuse while growing up, and 39% reported emotional abuse which occurred within the last 5 years (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2007). Emotional abuse is undefined in the TSI Life Event Questionnaire but occurred with a similar prevalence. Thus, although the cumulative prevalence of violence, abuse and neglect in the Impact of SARS Study appears high, it is possible that this reflects community norms.

There are few other studies of childhood adversity in healthcare workers for comparison. In the following studies, when confidence intervals were not reported they are estimated from the study's sample size. Regarding childhood sexual abuse, 18% of 323 registered nurses in Toronto (95% CI 14.2–22.6) had “a sexual experience for which you were either too young to give real consent or was forced on you” under the age of 16 (Gallop et al., 1995). Among 787 medical students and faculty in Rochester, 15% (95% CI 12.7–17.7) of reported physical and/or sexual abuse in childhood (deLahunta & Tulsky, 1996) and 10.8% (95% CI 7.7–14.8) reported childhood sexual abuse. Among 1,150 nurses and nurses aides in Mexico, 14% (95% CI 12–16) reported physical or sexual abuse in childhood (Diaz-Olavarrieta et al., 2001). While the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in the Impact of SARS study was higher, its confidence interval overlaps with each of these studies.

The results of this study suggest that childhood adversity occurs in healthcare workers with a prevalence that is not lower than the prevalence in the community. It appears that the “selection filters” of higher education and persistence in a stressful occupation do not act independently to produce a cohort with a low frequency of childhood adversity. It is plausible that early experience with adversity leads some individuals to seek opportunities to care for others. This choice may be reinforced by many positive consequences, including increased self-esteem and self-efficacy, the satisfaction that accompanies altruism, the vicarious satisfaction of protecting others, and the benefits of being appreciated. At the same time, not every individual who chooses this path will have the resources and resilience to complete their education, train in a profession, and tolerate to stresses of a career in healthcare. Thus, it is possible that healthcare workers who have experienced abuse represent a biased sample which is skewed toward resilient outcomes of early abuse. Further research, incorporating measures of resilience, including constructs such as posttraumatic growth, self-esteem, and sense of coherence and directly comparing healthcare workers to members of the lay community could provide answers.

In North American hospitals, most healthcare workers are nurses, and most are women. Little is known about how a personal history of physical or sexual abuse affects a nurse's ability to practice her profession and how it alters the impact of work stress on her. On the positive side, the personal experience of severe adversity may lead a healthcare worker to be more attentive to the suffering of her patients, more alert to signs of unreported victimization, or more dedicated to helping others. However, personal experiences of abuse may also impair assertiveness and self-esteem (Gallop et al., 1995). Two studies have found the childhood sexual abuse is associated with depression, distress and low self-esteem in nursing students (Rew, 1989) and nurses (Gallop et al., 1995). Nurses who had experienced abuse identified that problems with self-worth, trust, and assertiveness affected their practice and relationships with other team members (Gallop et al., 1995). The current study's finding that childhood violence, abuse and neglect is associated with psychological distress and impairment reinforces these concerns.

We hypothesized that childhood exposure to adversity would be associated with the stressful impact of adult life events. We found a strong relationship between a history of childhood adversity and the number of life events that occur as an adult. Because this is a retrospective study, we cannot rule out the possibility that recent life events are spuriously increased in people with greater psychological distress due to recall or reporting bias. However, we believe that this explanation of the results is unlikely because most of the recent events which were probed require little interpretation or recall effort (e.g., In the last 6 months I purchased a house or car, I broke up with my partner, I had to ask for money from a bank, etc.). Furthermore, our retrospective finding is consistent with previous prospective research (Berkman, Leo-Summers, & Horwitz, 1992) which increases confidence in its validity.

We found a non-linear relationship between adverse life events and psychological distress. Compared with healthcare workers who did not experience childhood violence, abuse or neglect, healthcare workers with childhood adversity were both much more likely to experience a high number of life events and greater psychological distress. We were unable to directly test the hypothesis that the experience of childhood adversity moderates the relationship between adult life events and psychological distress in healthcare workers (i.e., that childhood adversity results in a steeper slope in this relationship) for 2 reasons. First, life events were only significantly associated with distress above a threshold (6 major events/6 months in this sample). Second, the subsample for whom a difference between groups could be tested (healthcare workers with more than 6 major events/6 months) was under-powered for detecting an interaction. Thus, the failure to distinguish between the slopes in healthcare workers with adversity (rho = .50) and those without childhood adversity (rho = .32), among healthcare workers with a high number of life events, may be due to Type II error.

Non-linear (positive curvilinear) relationships between cumulative childhood adversity and adverse adult outcomes have been reported in studies using different methodologies than were used in this study (Hammen et al., 2000, Schilling et al., 2008). The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, in particular, has found graded (and often curvilinear) relationships between the number of childhood adverse experiences and many adverse outcomes later in life including autobiographical memory disturbance, receiving psychotropic medication, adolescent alcohol use, teen pregnancy, adult depression, attempted suicide, and liver disease (Anda et al., 2007, Brown et al., 2007, Chapman et al., 2004, Dong et al., 2003, Dube et al., 2001, Dube et al., 2006, Hillis et al., 2004). The current study, on the other hand, suggests that the experience of any childhood violence, abuse or neglect may be associated with one's position in a positive curvilinear relationship between adult life events and psychological distress.

The second hypothesis, that childhood adversity is associated with occupational impairment, is supported by the finding that childhood adversity is associated with days off work due to stress and illness. This is an important convergent finding; childhood adversity was not only associated with subjective distress but with apparent functional impairment. Future research should incorporate objective measures of function to replicate this finding.

Childhood adversity was inversely associated with perceived availability of social support, which confirms in healthcare workers a trend that has been observed previously in others (Kendall-Tackett, 2002). Childhood adversity was associated with responding to more severe recent stresses with feelings of hopelessness, helplessness and fear, which is also consistent with observations in other populations (Arata et al., 2007, Gibb et al., 2001). Unlike previous studies (Griffing et al., 2006, Rew and Christian, 1993) in this sample childhood adversity was not associated with differential coping responses. The lack of association between childhood adversity and coping may be because we measured coping with an unusual event—an outbreak of infectious disease. Since childhood maltreatment has previously been linked to avoidant types of coping (Griffing et al., 2006) and responses to the SARS outbreak were typified by avoidant and distancing strategies in general (Maunder, 2004, Maunder et al., 2006) the nature of the event may have minimized between-group differences.

It is consistent with the theory of polyvictimization (Finkelhor et al., 2007) that there is a gradient of increasing distress from healthcare workers with no childhood violence abuse or neglect to healthcares workers with one event to healthcare workers who experienced two or more types of childhood adversity. Study designed to address this question should include a broader range of childhood exposures including exposure to bullying.

The data support the resilience of the healthcare workers who participated. While there is good evidence from prospective studies that child abuse is a risk factor for mental illness, addictions, and other health problems (Horwitz et al., 2001, Roberts et al., 2004, Spataro et al., 2004) these problems were not common among participants in the Impact of SARS Study (Lancee et al., 2008). For example, a lifetime prevalence of major depression of 11.9% in this largely female, middle aged cohort is similar or lower than is found in the general Canadian population (Patten, 2000) and was not more common among workers with a history of violence, abuse or neglect. Resilience to childhood adversity is recognized as a common outcome but the sources of resilience are not fully understood (Collishaw et al., 2007). Since resilience has sometimes been defined as the absence of psychiatric diagnoses or other indicators of psychopathology, it is noteworthy that the strong relationship between life stress and distress found in this study may represent one of the best-case-scenario outcomes for serious childhood adversity.

This study has important methodological limitations. The Impact of SARS study was designed to study the long-term stressful impact of an infectious disease, not to provide an estimate of the prevalence of sexual and physical abuse in healthcare workers. This analysis is thus subject to the limitations that result from performing a secondary analysis on data that were collected for a different purpose. For example, the gender distribution in this study is unbalanced, which limits conclusions about male healthcare workers. Participants were recruited from medical and surgical units based on their willingness to participate, which means that self-selection due to variables that are related to abuse history is possible. We have addressed this concern by performing a second survey (participation rate = 99%) that compared participants in the Impact of SARS Study to their nonparticipating colleagues working in the same unit. There were no differences with respect to age, gender, healthcare experience, profession and the degree to which they found SARS to be a negative experience (Maunder et al., 2006) which suggests that any biases that are due to self-selection are subtle. We had extensive psychological data to compare participants in the full Impact of SARS survey (n = 769) and those in the second wave study reported here (n = 176) and so we can be very confident that the smaller group is not a psychologically biased sample (Lancee et al., 2008). The use of a self-report questionnaire and the use of the word “abuse” within the questionnaire may have resulted in lower rates of abuse than would be found by interview or with questions requiring less interpretation. Retrospective reporting of coping, 1–2 years after the event, is prone to inaccuracy due to biased recall (Ptacek, Smith, Espe, & Raffety, 1994).

A personal history of violence, abuse or neglect is common in healthcare workers. The well-being of healthcare workers is critical to the effectiveness of an over-taxed healthcare system. Although healthcare workers may be resilient as a group, the cumulative impact of stress on abused healthcare workers is substantial. Attitudes of shame and blame have historically led to a silencing of the victims of abuse and have stifled constructive social responses to the problem. An open discussion within the field of healthcare is required which acknowledges the strengths and vulnerabilities that accompany extraordinary personal adversity, and which supports healthcare workers in their efforts to establish and maintain a working environment that is safe, supportive and flexible and facilitates the best possible patient care.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Deborah Sinclair with this project.

Footnotes

This study was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (SAR-67807).

References

- Aiken L.H., Clarke S.P., Sloane D.M. Hospital staffing, organization, and quality of care: Cross-national findings. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2002;14:5–13. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L.H., Clarke S.P., Sloane D.M., Sochalski J., Silber J.H. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda R.F., Brown D.W., Felitti V.J., Bremner J.D., Dube S.R., Giles W.H. Adverse childhood experiences and prescribed psychotropic medications in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata C.M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling J., Bowers D., O’Brien N. Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:393–415. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L.F., Leo-Summers L., Horwitz R.I. Emotional support and survival after myocardial infarction. A prospective, population-based study of the elderly. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1992;117:1003–1009. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.W., Anda R.F., Edwards V.J., Felitti V.J., Dube S.R., Giles W.H. Adverse childhood experiences and childhood autobiographical memory disturbance. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman D.P., Whitfield C.L., Felitti V.J., Dube S.R., Edwards V.J., Anda R.F. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw S., Pickles A., Messer J., Rutter M., Shearer C., Maughan B. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:211–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deLahunta E.A., Tulsky A.A. Personal exposure of faculty and medical students to family violence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275:1903–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Olavarrieta C., Paz F., Garcia de la Cadena C., Campbell J. Prevalence of intimate partner abuse among nurses and nurses’ aides in Mexico. Archives of Medical Research. 2001;32:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(00)00262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M., Dube S.R., Felitti V.J., Giles W.H., Anda R.F. Adverse childhood experiences and self-reported liver disease: New insights into the causal pathway. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:1949–1956. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.16.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Anda R.F., Felitti V.J., Chapman D.P., Williamson D.F., Giles W.H. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Miller J.W., Brown D.W., Giles W.H., Felitti V.J., Dong M., Anda R.F. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:444–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan S.M., Hyndman K., Estabrooks C.A., Hesketh K., Humphrey C.K., Wong J.S., Acorn S., Giovannetti P. Nurses’ experience of violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2001;32:57–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embriaco N., Papazian L., Kentish-Barnes N., Pochard F., Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2007;13:482–488. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes C.M., Bouthillette F., Raboud J.M., Bullock L., Moore C.F., Christenson J.M., Grafstein E., Rae S., Ouellet L., Gillrie C., Way M. Violence in the emergency department: A survey of health care workers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1999;161:1245–1248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Ormrod R.K., Turner H.A. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Ormrod R.K., Turner H.A., Hamby S.L. The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour. 1980;21:219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. Mind Garden; Palo Alto, CA: 1988. Ways of Coping Questionnaire Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P.A., Tix A.P., Barron K.E. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gallop R., McKeever P., Toner B., Lancee W., Lueck M. The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the psychological well-being and practice of nurses. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1995;9:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(95)80036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb B.E., Alloy L.B., Abramson L.Y., Rose D.T., Whitehouse W.G., Hogan M.E. Childhood maltreatment and college students’ current suicidal ideation: A test of the hopelessness theory. Suicide Life Threatening Behaviour. 2001;31:405–415. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.4.405.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffing S., Lewis C.S., Jospitre T., Chu M., Sage R., Primm B.J., Madry L. The process of coping with domestic violence in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2006;15:23–41. doi: 10.1300/J070v15n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsdottir S., Clarke S.P., Rafferty A.M., Nutbeam D. Front-line management, staffing and nurse-doctor relationships as predictors of nurse and patient outcomes. A survey of Icelandic hospital nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46(7):920–927. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C., Henry R., Daley S.E. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S.D., Anda R.F., Dube S.R., Felitti V.J., Marchbanks P.A., Marks J.S. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113:320–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz A.V., Widom C.S., McLaughlin J., White H.R. The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: A prospective study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:184–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S.W. The wounded healer. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 2001;75:1–36. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2001.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett K. The health effects of childhood abuse: Four pathways by which abuse can influence health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:715–729. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.L., Walters E.E., Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimaki M., Ferrie J.E., Head J., Shipley M.J., Vahtera J., Marmot M.G. Organisational justice and change in justice as predictors of employee health: The Whitehall II study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:931–937. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluska K.M., Laschinger H.K., Kerr M.S. Staff nurse empowerment and effort-reward imbalance. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership. 2004;17:112–128. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2004.16247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancee W.J., Maunder R.G., Goldbloom D.S., Balderson K.E., Bennett J.P., Borgundvaag B., Jr., Evans S., Fernandes C.M.B., Gupta M., McGillis Hall L., Hunter J.J., Nagle L.M., Pain C., Peczeniuk S.S., Raymond G., Read N., Rourke S.B., Steinberg R.J., Stewart T.E., VanDeVelde-Coke S., Veldhorst G.H., Wasylenki D.A. The prevalence of mental disorders in Toronto hospital workers one to two years after SARS. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:91–95. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist L.O., Ahlstrom G. Psychometric evaluation of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire as applied to clinical and nonclinical groups. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan H.L., Fleming J.E., Trocmé N., Boyle M.H., Wong M., Racine Y.A., Beardslee W.R., Offord D.R. Prevalence of child physical and sexual abuse in the community. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marziali E.A., Pilkonis P.A. The measurement of subjective response to stressful life events. Journal of Human Stress Survivorship and Therapy. 1986;2:5–12. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1986.9936760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: Lessons learned. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London – Series B: Biological Sciences. 2004;359:1117–1125. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder R.G., Lancee W.J., Balderson K.E., Bennett J.P., Borgundvaag B., Evans S., Fernandes C., Goldbloom D.S., Gupta M., Hunter J.J., McGillis-Hall L., Nagle L.M., Pain C., Peczeniuk S.S., Raymond G., Read N., Rourke S.B., Steinberg R.J., Stewart T., VanDeVelde-Coke S., Veldhorst G.G., Wasylenki D.A. Longterm psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12:1924–1932. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillis-Hall L., Kiesners D. A narrative approach to understanding the nursing work environment in Canada. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:2482–2491. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T.W., Veltkamp L.J., Heister T.A., Shirley P. Clinical assessment of adult abuse and trauma. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 1998;28:349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Patten S.B. Incidence of major depression in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2000;163:714–715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek J.T., Smith R.E., Espe K., Raffety B. Limited correspondence between daily coping reports and retrospective coping recall. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2007). What is emotional abuse? Retrieved July 12, 2007, from www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ncfv-cnivf/familyviolence/html/fvemotion_e.html.

- Rew L. Childhood sexual exploitation: Long-term effects among a group of nursing students. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1989;10:181–191. doi: 10.3109/01612848909140842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L., Christian B. Self-efficacy, coping, and well-being among nursing students sexually abused in childhood. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1993;8:392–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexrode K.R., Petersen S., O’Toole S. The ways of coping scale—A reliability generalization study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2008;68:262–280. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R., O’Connor T., Dunn J., Golding J. The effects of child sexual abuse in later family life; mental health, parenting and adjustment of offspring. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:525–545. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling E.A., Aseltine R.H., Gore S. The impact of cumulative childhood adversity on young adult mental health: Measures, models, and interpretations. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spataro J., Mullen P.E., Burgess P.M., Wells D.L., Moss S.A. Impact of child sexual abuse on mental health: Prospective study in males and females. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184:416–421. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence-Laschinger H.K., Sabiston J.A., Finegan J., Shamian J. Voices from the trenches: Nurses’ experiences of hospital restructuring in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership. 2001;14:6–13. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2001.16305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A., Greenfield S., Hays R., Wells K., Rogers W.H., Berry S.D., McGlynn E.A., Ware J.E., Jr. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeltanz N.D., Wilsnack S.C., Harris T.R., Wilsnack R.W., Wonderlich S.A., Kristjanson A.F. Prevalence and risk factors for childhood sexual abuse in women: National survey findings. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:579–592. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyers S., Peter R., Boggild H., Jeppesen H.J., Siegrist J. Psychosocial work stress is associated with poor self-rated health in Danish nurses: A test of the effort-reward imbalance model. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2006;20:26–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]