Abstract

Rationale

Alcohol and nicotine addiction are prevalent conditions that co-occur. Despite the prevalence of co-use, factors that influence the suppression and enhancement of concurrent alcohol and nicotine intake are largely unknown.

Objectives

Our goals were to assess how nicotine abstinence and availability influenced concurrent alcohol consumption, and to determine the impact of quinine adulteration of alcohol on aversion resistant alcohol consumption and concurrent nicotine consumption.

Methods

Male and female C57BL/6J mice voluntarily consumed unsweetened alcohol, nicotine and water in a chronic 3-bottle choice procedure. In Experiment 1, nicotine access was removed for 1 week and re-introduced the following week, while the alcohol and water bottles remained available at all times. In Experiment 2, quinine (100–1000 μM) was added to the 20% alcohol bottle, while the nicotine and water bottles remained unaltered.

Results

In Experiment 1, we found that alcohol consumption and preference were unaffected by the presence or absence of nicotine access in both male and female mice. In Experiment 2a, we found that quinine temporarily suppressed alcohol intake and enhanced concurrent nicotine, but not water, preference in both male and female mice. In Experiment 2b, chronic quinine suppression of alcohol intake increased nicotine consumption and preference in female mice without affecting water preference, whereas it increased water and nicotine preference in male mice.

Conclusions

Quinine suppression of alcohol consumption enhanced the preference for concurrent nicotine preference in male and female mice, suggesting that mice compensate for the quinine adulteration of alcohol by increasing their nicotine preference.

Keywords: Alcohol, nicotine, quinine, addiction, aversion, mice, consumption

Introduction

Alcohol and nicotine are the two most commonly abused addictive drugs and the majority of alcohol dependent individuals are also dependent on nicotine (Batel et al., 1995; Falk et al., 2006; Miller and Gold, 1998). Persons co-dependent on alcohol and nicotine have more severe drug dependence symptoms such as greater craving and withdrawal signs, higher drug consumption, increased difficulty maintaining abstinence, and have higher mortality compared with persons dependent on alcohol or nicotine alone (Heffner et al., 2011; Hurt et al., 1996; King et al., 2009; Leeman et al., 2008; Marks et al., 1997). Despite the high prevalence and increased health consequences of alcohol and nicotine co-dependence, there are currently no FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of alcohol and nicotine co-dependence. In human studies, it is difficult to dissect the effects of alcohol and nicotine from the genetic and environmental influences that also contribute to overall drug taking. Several reviews have highlighted key knowledge gaps that have limited the development of new drugs, such as the need to better understand the neurobiology of co-dependence and the need for identification of drug targets that mediate both alcohol and nicotine dependence (Tarren and Bartlett, 2017; Van Skike et al., 2016). To achieve this, the development of a greater variety of animal models that reflect alcohol and nicotine co-use is necessary, as this will enable the identification how alcohol and nicotine influence co-consumption while controlling for genetics and environment.

Many animal models of alcohol and nicotine co-dependence utilize investigator administered drugs (Blomqvist et al., 1996; Hendrickson et al., 2009; Lê et al., 2000, 2003; Smith et al., 2002), and although these models allow for control of dose and timing, they do not permit the animal to voluntarily consume both drugs. A limited number of studies in rats have examined voluntary alcohol and nicotine intake using several routes of administration, such as intravenous self-administration (IVSA) of nicotine with operant oral consumption of alcohol (Lê et al., 2010, 2014), IVSA nicotine with oral alcohol consumption in a 2-bottle choice procedure (Maggio et al., 2018), operant intra-cranial self-administration of nicotine with operant alcohol consumption (Deehan et al., 2015), or operant intra-cranial self-administration of a mixture of alcohol and nicotine (Truitt et al., 2015). These studies provide valuable information, yet the procedures involve significant training as well as technical and surgical requirements. In contrast, 2-bottle choice studies are frequently used in rats and mice to assess alcohol or nicotine consumption (Lee and Messing, 2011; Lee et al., 2014; Locklear et al., 2012; Meliska et al., 1995; Powers et al., 2013; Simms et al., 2008). In these studies, the animals are individually housed with two fluid bottles, one containing drug and one water, and the animals are free to consume from both bottles. These bottle choice studies are less technically challenging and are more high-throughput compared with operant administration studies.

We have previously developed a novel 3-bottle choice co-consumption model where mice voluntarily consume unsweetened alcohol, unsweetened nicotine, and water from 3 separate drinking bottles (O’Rourke et al., 2016; Touchette et al., 2018; DeBaker et al., 2019). Using this model, we investigated the effects of forced alcohol abstinence and intermittent drug access, and the impact of preclinical drug treatment on concurrent alcohol and nicotine consumption in male and female C57BL/6J mice (O’Rourke et al., 2016; Touchette et al., 2018). We reported that after 3 weeks of chronically co-consuming alcohol and nicotine, forced alcohol abstinence resulted in an increase in concurrent nicotine consumption and preference in male and female C57BL/6J mice, suggesting that the mice compensated for the absence of alcohol by increasing their consumption of nicotine (O’Rourke et al., 2016). It is unclear if the reciprocal relationship between alcohol and nicotine is true, and in the current study one of our goals was to determine whether forced nicotine abstinence enhanced concurrent alcohol consumption in this model.

A prominent feature of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) in humans is consumption of alcohol despite adverse legal, health, economic, and societal consequences. The continued consumption of alcohol despite the addition of the bitter tastant quinine has been frequently used as a model of compulsive alcohol intake or aversion-resistant alcohol consumption in both rats and mice (Hopf et al., 2010; Hopf and Lesscher, 2014; Lei et al., 2016; Sneddon et al., 2019; Spanagel et al., 1996). Our second goal was to determine whether the alcohol-abstinence induced elevation of nicotine consumption that we previously reported in O’Rourke et al, 2016 could be produced by suppressing alcohol consumption instead of removing alcohol access. Moreover, quinine suppression of alcohol consumption has not yet been evaluated in a voluntary alcohol and nicotine co-consumption model.

Here, we report an unequal interaction between alcohol and nicotine, where alcohol consumption is unaffected by the presence or absence of nicotine access. In contrast, the addition of quinine temporarily suppressed alcohol preference and enhanced concurrent nicotine preference in both sexes. Chronic suppression of alcohol consumption with quinine produced a long-term enhancement of concurrent nicotine, but not water, preference in female mice, and enhanced both nicotine and water preference in male mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Reagents

12 male and 12 female C57BL/6J mice from The Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA) acclimated to our facility for at least six days before beginning behavioral experiments at 55 days old. All mice underwent both experimental procedures. Mice were group housed in standard cages under a 12-h light/dark cycle until the start of behavioral experiments, after which they were individually housed. Food and water were freely available at all times. All animal procedures were in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota, and conformed to NIH guidelines.

Alcohol (ethanol) (Decon Labs, King of Prussia, PA), and nicotine tartrate salt (Acros Organics, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Chicago, IL) were mixed with tap water to the concentrations reported for each experiment. The concentrations of nicotine are reported as free base, and nicotine solutions were not filtered or pH adjusted. The alcohol, nicotine and water bottles were unsweetened at all times. Quinine hydrochloride (Spectrum Chemical Manufacturing Corp, Gardena, CA) was added to the 20% alcohol bottle at concentrations of 100, 200, 500 and 1000 μM in Experiment 2.

Experiment 1: Effects of nicotine abstinence on concurrent alcohol consumption

Mice were singly housed in custom cages that accommodated three drinking bottles (Ancare, Bellmore, NY) containing water, nicotine or alcohol at different concentrations. The concentrations for the first week consisted of 3% alcohol (v/v) in one bottle, 5 μg/mL nicotine in the second bottle and water in the third bottle. The concentrations for the second week were 10% alcohol and 15 μg/mL nicotine, and were 20% alcohol and 30 μg/mL nicotine for the third week. During the fourth week, the nicotine bottle was removed and the 20% alcohol and water bottles remained available. During the fifth week, all three bottles were again presented at the 20% alcohol and 30 μg/mL nicotine concentrations. Food was freely available and the mice were not fluid restricted at any time. The bottles were weighed every other day and the solutions refreshed every 3–4 days. The positions of the bottles were alternated after each weighing to account for side preferences. Mice were weighed once a week. Fluid evaporation and potential dripping were accounted for by the presence of a set of alcohol, nicotine and water bottles on an empty control cage. The weight of fluid loss from these bottles was subtracted from all bottle weights throughout the study.

Experiment 2: The impact of quinine adulteration on concurrent alcohol and nicotine consumption

Immediately after completion of Experiment 1, the mice proceeded to Experiment 2 without a break in alcohol or nicotine consumption. In Experiment 2a, quinine (100 μM) was added to the 20% alcohol bottle for 3 days (acute phase), while the water and 30 μg/mL nicotine bottles remained unaltered. In Experiment 2b, the quinine concentration in the 20% alcohol bottle was increased to 200, 500 and 1000 μM, with each concentration presented for 6 days (chronic phase). The 0 quinine concentrations reported were the average consumption and preference of 20% alcohol and 30 μg/mL nicotine during the prior week (Week 5 of Experiment 1). The bottles were weighed and rotated every day and the mice were weighed once a week. Fluid evaporation and bottle dripping were controlled for by the presence of a set of bottles on an empty control cage. The weight of fluid loss from these bottles was subtracted from all bottles throughout the study.

Statistical Analysis

The average daily alcohol (g/kg) and nicotine consumption (mg/kg) for each drug concentration was calculated based on the weight of the fluid consumed from the bottles, the density of the solution (for alcohol only), and the weight of the individual mouse. The percent preference for alcohol, nicotine, and water bottles was calculated as the weight of the fluid consumed from the bottle of interest, divided by the summed weight of fluid consumed from all three bottles, multiplied by 100. All analyses were calculated using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Data were tested for normality and variance.

For all experiments, data were analyzed by repeated measures (RM) 2-way ANOVA, followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests to examine the effect of sex and time. For all experiments, sex differences in the average consumption of alcohol (g/kg) and nicotine (mg/kg), and in the average preference for the alcohol, nicotine and water bottles are described first, followed by the time effects of forced nicotine abstinence (Experiment 1) or of quinine adulteration of alcohol (Experiment 2).

Results

Experiment 1: Effect of forced nicotine abstinence on concurrent alcohol consumption

A schematic outline of our experiments is shown in Figure 1. In Experiment 1, we evaluated the effect of forced nicotine abstinence on concurrent alcohol consumption and preference. Male and female C57BL/6J mice had continuous access to alcohol (v/v), nicotine (μg/mL) and water for 3 weeks in a 3-bottle choice procedure, with drug concentrations of 3% alcohol and 5 μg/mL nicotine presented during Week 1, 10% alcohol and 15 μg/mL nicotine during Week 2 and 20% alcohol and 30 μg/mL nicotine presented during Week 3. During Week 4, the nicotine bottle was removed and mice had access to the 20% alcohol and water bottles. The nicotine bottle was re-introduced in Week 5. Drug consumption and preference data for the entire experiment (Weeks 1–5) was analyzed using RM 2-way ANOVA comparisons followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests.

Fig. 1. Schematic of experimental procedures.

Unsweetened alcohol % (A, v/v), nicotine (N, μg/mL) and water were presented in a 3-bottle choice consumption procedure. Quinine (Q, μM) was added to the 20% alcohol bottle in Experiment 2

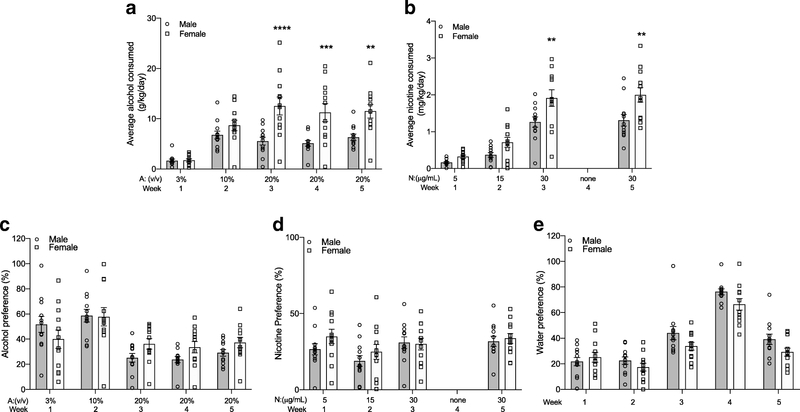

We first examined the data for sex differences between male and female mice. For alcohol consumption, we found a significant sex by time interaction, a main effect of time and a main effect of sex (FsexXtime(4,88)=6.6061, P=0.0002; Fsex(1,22)=14.49, P=0.001; Ftime(4,88)=26.39, P<0.0001). Multiple comparisons tests showed that female mice consumed more average alcohol (g/kg/day) compared with male mice during Weeks 3–5 (Figure 2A). Female mice also consumed more nicotine (mg/kg/day) compared with male mice during Weeks 3 and 5 (FsexXtime(3,66)=3.070, P=0.03; Fsex(1,22)=8.776, P=0.007; Ftime(3,66)=98.28, P<0.0001, Figure 2B). For alcohol preference, we found a significant sex by time interaction, no main effect of sex and a main effect of time (FsexXtime(4,88)=2.928, P=0.03; Fsex(1,22)=0.4167, P=0.52; Ftime(4,88)=19.84, P<0.0001); however, multiple comparisons tests did not identify a difference between male and female alcohol preference at any week (Figure 2C). For nicotine preference, we found a main effect of time and no main effect of sex or a sex by time interaction (FsexXtime(3,66)=1.408, P=0.25; Fsex(1,22)=0.689, P=0.42; Ftime(3,66)=7.631, P<0.001, Figure 2D). Finally, for water preference we found main effects of sex and time without an interaction between sex and time (FsexXtime(4,88)=1.597, P=0.18; Fsex(1,22)=4.365, P=0.049; Ftime(4,88)=78.26, P<0.0001, Figure 2E).

Fig. 2. Female mice consume more alcohol and nicotine compared with male mice in Experiment 1 - effects of nicotine abstinence on concurrent alcohol consumption.

(A) Alcohol and (B) nicotine consumption by weight in male and female mice. (C) Alcohol, (D) nicotine and (E) water preference over time in male and female mice. Sidak’s post-hoc test between male and female mice for the same week **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. n=12 per sex, mean ± SEM

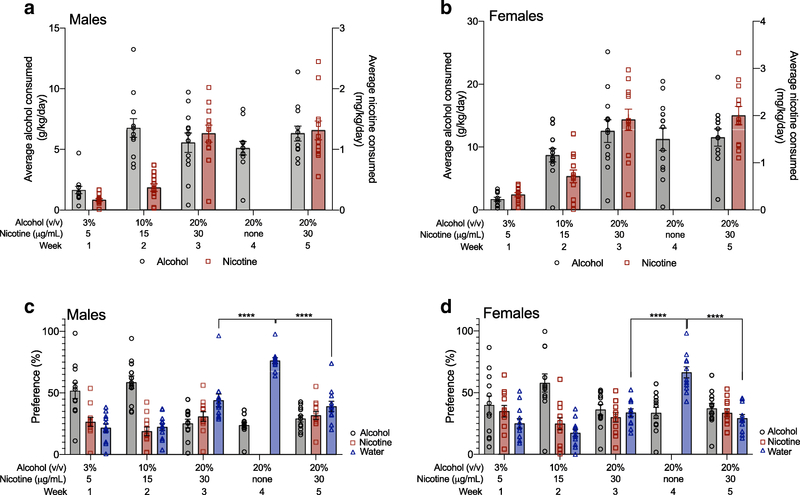

We then examined the effect of forced nicotine abstinence during Week 4 on the consumption of 20% alcohol and 30 μg/mL nicotine, and the preference for each of the three bottles using Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests, since we found main effects of time or interactions between sex and time. For alcohol consumption, we found that male mice had no significant differences in 20% alcohol consumption across Weeks 3–5, indicating that removal of the nicotine bottle had no effect on alcohol consumption (Figure 3A). Forced nicotine abstinence during Week 4 also did not affect 30 μg/mL nicotine consumption in male mice as the level of nicotine consumption for Weeks 3 and 5 were not significantly different, indicating that no compensatory increase in nicotine consumption occurred after forced abstinence (Figure 3A). We found similar results in female mice, with no significant differences in 20% alcohol consumption across Weeks 3–5, and no significant differences in 30 μg/mL nicotine consumption across Weeks 3 and 5 (Figure 3B). For alcohol preference, we found no significant changes in alcohol preference across Weeks 3–5 in male mice (Figure 3C), or in female mice (Figure 3D). The preference for the 30 μg/mL nicotine bottle not significantly different across Weeks 3 and 5 for male (Figure 3C) or female mice (Figure 3D). Examining the water preference showed that the preference for the water bottle during Week 4 was significantly higher than during Weeks 3 or 5 in both males and females, suggesting that removal of the nicotine bottle elevated only water preference in both sexes (Figure 3C–D). Overall, Experiment 1 showed that female mice consumed more alcohol and nicotine than male mice, and forced nicotine abstinence during Week 4 had no effect on 20% alcohol or 30 μg/mL nicotine consumption or preference, but increased only the preference for the water bottle during Week 4 in both male and female mice.

Fig. 3. Nicotine forced abstinence increases concurrent water preference, and not alcohol preference, in male and female mice.

Average alcohol (g/kg) and nicotine (mg/kg) consumption in (A) male and (B) female mice. Preference for the alcohol, nicotine and water bottles for (C) male and (D) female mice. Removal of the nicotine bottle during Week 4 increased the preference for the water bottle but not the alcohol bottle in (C) male and (D) female mice. Sidak’s post-hoc test ****P<0.0001 between Weeks 3 and 4, and between Weeks 4 and 5. n=12 per sex, mean ± SEM

Experiment 2a: The impact of quinine adulteration on concurrent alcohol and nicotine consumption

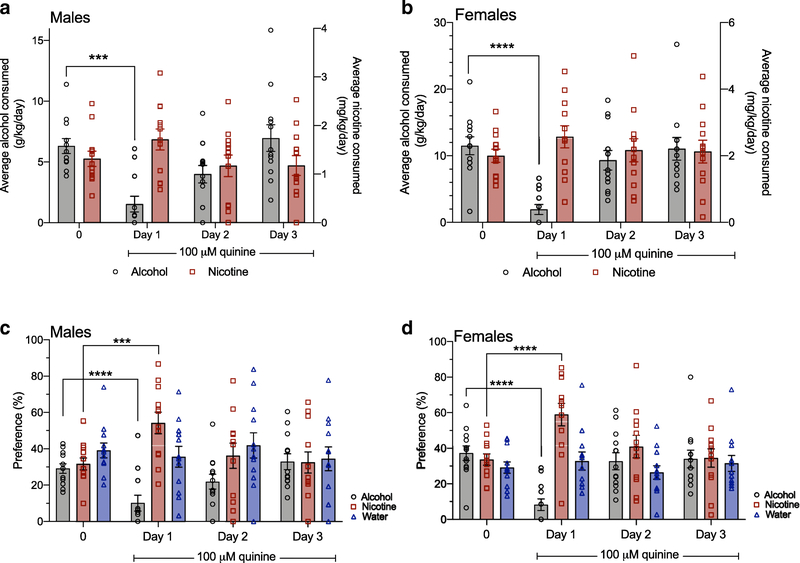

We tested the effect of quinine adulteration of 20% alcohol on concurrent alcohol and nicotine consumption in male and female C57BL/6J mice. Quinine (100 μM) was added to the 20% alcohol bottle for 3 days, and the average daily consumption of alcohol and nicotine during quinine adulteration was compared with the average daily consumption during the prior week when no quinine was present (Week 5 of Experiment 1). We first examined consumption and preference across sex as in Experiment 1. For alcohol consumption, we found a significant sex by time interaction, a main effect of sex and a main effect of time (FsexXtime(3,66)=4.142, P=0.009; Fsex(1,22)=9.280, P=0.006; Ftime(3,66)=36.37, P<0.0001). Multiple comparisons testing showed that female mice consumed more alcohol compared with male mice for all time points except for Day 1 (Figure 4A). For nicotine consumption, there were main effects of sex and time without a significant interaction, with females consuming more nicotine compared with males (FsexXtime(3,66)=0.2655, P=0.85; Ftime(3,66)=3.367, P=0.02; Fsex(1,22)=8.908, P=0.007, Figure 4B). For both alcohol and nicotine preference, there were main effects of time with no main effects of sex, or sex by time interactions (alcohol preference: FsexXtime(3,66)=2.415, P=0.07; Ftime(3,66)=35.99, P<0.0001; Fsex(1,22)=0.87, P=0.36; nicotine preference: FsexXtime(3,66)=0.088, P=0.97; Ftime(3,66)=17.03, P<0.0001; Fsex(1,22)=0.2834, P=0.60). For water preference, we found no main effect of sex or time, and no interaction between sex and time (FsexXtime(3,66)=1.450, P=0.24; Ftime(3,66)=0.05, P=0.98; Fsex(1,22)=1.846, P=0.19, preference data for all three bottles are shown separately by sex on Figure 5C and 5D).

Fig. 4. Female mice consume more alcohol and nicotine compared with male mice in Experiment 2a – effects of acute quinine adulteration of alcohol.

(A) Alcohol consumption by weight in male and female mice. Sidak’s post-hoc test between male and female mice for the same time point *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (B) Nicotine consumption by weight in male and female mice. There was a main effect of sex on nicotine consumption. n=12 per sex, mean ± SEM

Fig. 5. Temporary quinine-induced suppression of alcohol intake produces an increase in concurrent nicotine preference.

Addition of 100 μM quinine to the 20% alcohol bottle occurred on Days 1–3. Quinine suppressed alcohol consumption on Day 1 in (A) male mice and (B) female mice compared to the average alcohol consumption at the 0 quinine concentration. Sidak’s multiple comparisons test ***P<0.0001, ****P<0.0001 for Day 1 compared with 0. Quinine suppressed alcohol preference and increased nicotine preference on Day 1 in (C) male mice and (D) female mice. Sidak’s multiple comparisons test ***P<0.0001, ****P<0.0001 for Day 1 compared with the 0 quinine concentration for alcohol and nicotine preference. n=12 per sex, mean ± SEM

We then examined alcohol and nicotine consumption, and preference for each bottle over time, since we observed main effects of time or interactions between sex and time. We found that 100 μM quinine temporarily suppressed alcohol consumption and alcohol preference in male mice (Figure 5A and 5C) and in female mice (Figure 5B and 5D) on Day 1. As female mice consumed more alcohol compared with male mice, we compared the magnitude of the quinine-adulterated alcohol suppression on Day 1 as a percent decrease from 0 levels, and found no significant difference between sexes (male: 74.5 ± 11.1% decrease; female: 76.7 ± 12.0% decrease, t=0.130, P=0.90). Quinine suppression of alcohol consumption and preference was temporary in both sexes, as both male and female mice overcame the 100 μM quinine suppression on Day 2. For concurrent nicotine preference, we found that the addition of 100 μM quinine to the 20% alcohol bottle produced a temporary increase in nicotine preference on Day 1 in male and female mice (Figure 5C and 5D). There was no significant increase in nicotine consumption on Day 1 in either sex. As there were no main effects of sex or time on water preference, as described above, the overall effect of 100 μM quinine adulteration of 20% alcohol was to reduce alcohol consumption and preference, and increase nicotine but not water preference in male and female mice.

Experiment 2b: The impact of chronic quinine adulteration on concurrent alcohol and nicotine consumption

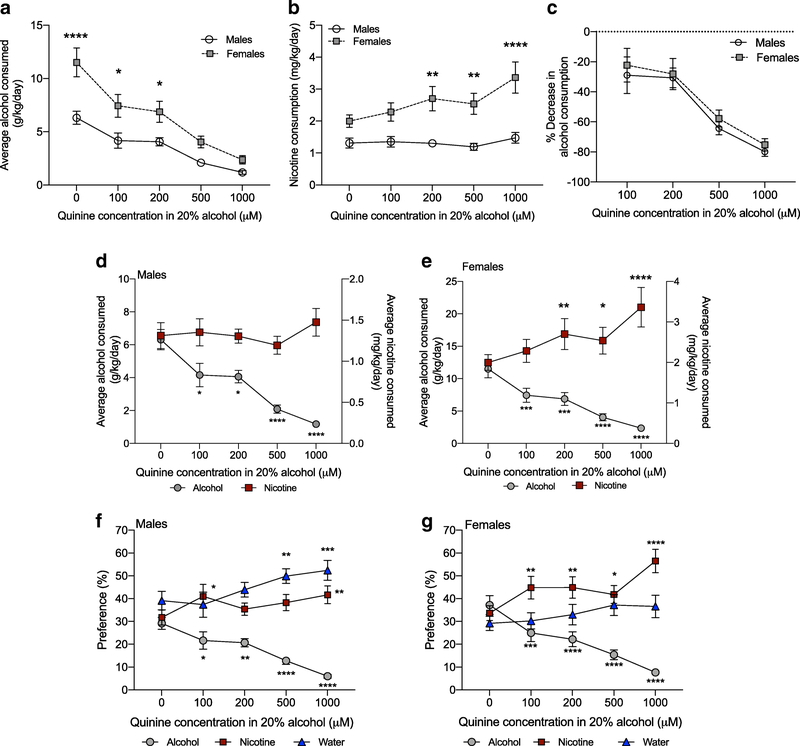

To determine the effect of chronic quinine adulteration of alcohol consumption on concurrent alcohol and nicotine intake, the quinine concentration in the 20% alcohol bottle was increased to 200, 500 and 1000 μM, with each concentration presented for 6 days. We first examined average daily drug consumption and preference across sex as in Experiment 1. For alcohol consumption, we found a significant interaction between sex and concentration, a main effect of sex and a main effect of concentration (FsexXconcentration(4,88)=3.602, P=0.009; Fsex(1,22)=14.01, P=0.001; Fconcentration(4,88)=47.13, P<0.0001). Multiple comparisons tests showed that female mice consumed more alcohol compared with male mice at the 0, 100 and 200 μM quinine concentrations (Figure 6A). For 30 μg/mL nicotine consumption, we found a significant interaction between sex and concentration, a main effect of sex and a main effect of concentration (FsexXconcentration(4,88)=5.156, P=0.0009; Fsex(1,22)=14.37, P=0.001; Fconcentration(4,88)=8.044, P<0.0001). Multiple comparisons tests showed that female mice consumed more nicotine compared with male mice at the 200, 500 and 1000 μM quinine concentrations (Figure 6B). For alcohol preference, we found a main effect of concentration with no main effect of sex, or a sex by concentration interaction (FsexXconcentration(4,88)=0.958, P=0.43; Fconcentration(4,88)=52.54, P<0.0001; Fsex(1,22)=1.318, P=0.26, alcohol preference for each sex is shown separately in Figure 6F and 6G). For nicotine preference, we found a significant interaction between sex and concentration, a main effect of concentration and no main effect of sex (FsexXconcentration(4,88)=2.835, P=0.03; Fsex(1,22)=1.704, P=0.21; Fconcentration(4,88)=13.76, P<0.0001); however, multiple comparisons tests did not reveal a significant difference in nicotine preference between sex at any concentration (Figure 6F and 6G). We also found main effects of sex and concentration with no interaction between sex and concentration for water preference, with male mice having an overall greater preference for water compared with female mice (FsexXconcentration(4,88)=0.893, P=0.47; Fconcentration(4,88)=8.695, P<0.0001; Fsex(1,22)=5.033, P=0.04; Figure 6F and 6G).

Fig. 6. Chronic suppression of alcohol intake by quinine increases nicotine consumption and preference.

(A) Female mice consume more alcohol and (B) more nicotine compared with male mice. Sidak’s post-hoc test between male and female mice at the same concentration *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. (C) Male and female mice have the same percent decrease in alcohol consumption over increasing quinine concentrations. (D) In male mice, increasing concentrations of quinine suppressed alcohol consumption without increasing nicotine consumption, whereas (E) in female mice, increasing concentrations of quinine suppressed alcohol consumption and increased concurrent nicotine consumption. Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 compared with the 0 quinine level within drug. (F) In male mice, increasing concentrations of quinine reduced alcohol preference, and increased nicotine and water preference, whereas (G) in female mice, increasing concentrations of quinine reduced alcohol preference and increased nicotine, but not water, preference. Sidak’s post-hoc test *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 compared with the 0 quinine level within each bottle. n=12 per sex, mean ± SEM

We then examined alcohol and nicotine consumption, and preference for each bottle over the increasing quinine concentrations, since we observed main effects of quinine concentration or interactions between sex and quinine concentration. We found that the average daily consumption and preference of 20% alcohol was significantly suppressed at all quinine concentrations in both male (Figure 6D and 6F) and female mice (Figure 6E and 6G). As female mice consumed more alcohol compared with male mice, we calculated the quinine-induced alcohol suppression as a percent of baseline alcohol consumption at the 0 quinine level. We found no significant difference in the magnitude of quinine-induced suppression between sexes over the increasing quinine concentrations, suggesting that quinine suppressed alcohol consumption to the same proportion in males and females, even though female mice consume more g/kg alcohol (FsexXconcentration(3,66)=0.05, P=0.99; Fsex(1,22)=0.397, P=0.53, Ftime(3,66)=31.99, P<0.0001, Figure 6C).

Chronic quinine adulteration of alcohol did not alter nicotine consumption at any time point in male mice (Figure 6D), whereas female mice increased their nicotine consumption at the 200, 500 and 1000 μM quinine concentrations compared with the 0 quinine concentration (Figure 6E). In male mice, we found that nicotine preference significantly increased when 100 and 1000 μM quinine was added to the 20% alcohol bottle, and water preference was significantly increased when 500 and 1000 μM quinine was added to the 20% alcohol bottle (Figure 6F). In female mice, the preference for the nicotine bottle was increased at all quinine concentrations, whereas water preference was not significantly changed at any quinine concentration (Figure 6G). Overall, these data showed that quinine suppressed alcohol consumption and preference equally in male and female mice, but female mice responded to chronic quinine adulteration of alcohol by increasing the consumption and preference of nicotine without changing water preference, whereas male mice increased both nicotine and water preference.

Discussion

In this study, we used a 3-bottle choice procedure that allows for voluntary, chronic co-consumption of alcohol and nicotine to investigate the suppression and enhancement of concurrent drug intake in male and female C57BL/6J mice. We and others have published data showing that female mice consume significantly more drug compared with male mice (Hwa et al., 2011; Kamens et al., 2010, 2012; O’Rourke et al., 2016; Touchette et al., 2018), and here we also report significant sex differences in alcohol and nicotine consumption in all our experiments. When we examined the impact of forced nicotine abstinence in Experiment 1, we found that alcohol consumption and preference is unaffected by forced nicotine abstinence or the re-introduction of nicotine access in both male and female C57BL/6J mice. In Experiment 2a, we found that addition of 100 μM quinine to the 20% alcohol bottle temporarily suppressed alcohol consumption and preference, while increasing concurrent nicotine preference in both male and female mice. In Experiment 2b, we found that chronic suppression of alcohol consumption with increasing concentrations of quinine increased both nicotine and water preference in male mice, and increased nicotine preference without affecting water preference in female mice. Our previous study showed that forced alcohol abstinence produced an enhancement in concurrent nicotine consumption and preference in male and female C57BL/6J mice (O’Rourke et al., 2016). Together with this study, our work showed that alcohol intake is unresponsive to the presence or absence of the nicotine bottle, but nicotine intake is influenced by the absence of alcohol consumption or by the adulteration of the alcohol bottle with quinine. In both studies, we used a 1-week forced abstinence period and it is possible that changes in concurrent alcohol consumption may require a longer abstinence duration.

One characteristic of AUD is the continued consumption of alcohol despite adverse consequences. Quinine adulteration of alcohol consumption in rodents has been frequently used to model aversion-resistant alcohol intake using quinine concentrations ranging from 25–500 μM (Hopf et al., 2010; Hopf and Lesscher, 2014; Lei et al., 2016; Lesscher et al., 2010; Sneddon et al., 2019; Spanagel et al., 1996). Quinine adulteration of alcohol consumption had not been previously examined in conjunction with concurrent nicotine consumption. In this study, we found that addition of 100 μM quinine to the alcohol bottle temporarily suppressed alcohol consumption and preference in both male and female mice. Interestingly, the suppression of alcohol intake was associated with increased preference for the nicotine bottle and not the water bottle. These data suggest that the mice compensate for the reduction in quinine-adulterated alcohol intake by selectively increasing preference for the unsweetened nicotine bottle, even though the water bottle is readily available. These results support our previous findings that nicotine consumption and preference is enhanced during forced alcohol abstinence (O’Rourke et al., 2016), and show that suppression of alcohol consumption, either by removing access to the alcohol bottle or reducing the palatability of alcohol, produces an enhancement of concurrent nicotine consumption.

The suppression of alcohol intake with 100 μM quinine was transient, as male and female mice overcame the aversion within one day. Our mice had been co-consuming alcohol and nicotine for 5 weeks prior to the introduction of quinine. A prior study in male C57BL/6J mice required 8 weeks of intermittent access consumption of 15% alcohol before resistance to 100 and 250 μM quinine develops (Lesscher et al., 2010). In addition, prior studies in rats have required a minimum of 3 months of intermittent alcohol consumption before the development of aversion resistant alcohol consumption to 0.1 g/L quinine (277 μM) in 5–20% alcohol concentrations (Hopf et al., 2010; Spanagel et al., 1996). However, a recent study by Lei and colleagues (2016) shows that a single session of unadulterated alcohol consumption is sufficient to produce aversion-resistant alcohol consumption to 100 μM quinine in 15% alcohol in male C57BL/6J mice (Lei et al., 2016), suggesting the duration of alcohol consumption required to achieve quinine resistance may be days, rather than weeks.

We increased the concentration of quinine in the alcohol bottle to determine the effect of long-term suppression of alcohol consumption on concurrent nicotine intake. We found that alcohol consumption was suppressed in a concentration-dependent manner in both male and female mice. Male mice showed increased preference for the nicotine and water bottles as the quinine concentration increased, suggesting that male mice compensated for the long-term suppression of alcohol intake by increasing their nicotine and water preference. In contrast, female mice showed increased nicotine consumption and preference as the quinine concentration increased, and did not show any increase in water preference. Thus, our data suggest that female mice compensated for the long-term suppression of alcohol intake by increasing their nicotine intake. These data illustrate an important sex difference in compensatory drug consumption and highlight the need to continue investigating both sexes to identify important differences that can influence addiction-related behaviors and potential treatment strategies. Nearly all of the prior research on aversion-resistant drinking has focused on male animals. One recent study by Sneddon and colleagues (2019) shows no sex difference in the proportion of 100 or 250 μM quinine-suppression of alcohol drinking in male and female C57BL/6J mice, even though female mice consume more 15% alcohol than males (Sneddon et al., 2019). Our data supports this finding, as male and female mice showed similar percent suppression of alcohol consumption as a result of increasing concentrations of quinine.

One limitation of our study is the lack of blood alcohol and nicotine levels. Since the mice are receiving access to the alcohol and nicotine bottles 24 hours a day, the consumption of alcohol and nicotine is spread out over time. Measuring blood alcohol and nicotine concentrations at an arbitrary time point is difficult due to the unsynchronized drug consumption and the fast metabolism of alcohol and nicotine in mice.

Alcohol and nicotine addiction are heritable disorders that share common genetic factors (Swan et al., 1996, 1997; True et al., 1999). The majority of tobacco smokers also use alcohol, yet smoking cessation trials frequently incorporate alcohol-related exclusion criteria and do not track co-use of alcohol in their subjects (Leeman et al., 2007), thus data on the treatment of co-users are lacking. Nearly one quarter of smokers report hazardous alcohol consumption patterns as defined by the NIAAA (Toll et al., 2012). These individuals have lower smoking cessation rates compared with moderate alcohol drinkers, highlighting that some co-users are less likely to successfully quit alcohol and nicotine use compared with other co-users (Toll et al., 2012). Varenicline (an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) partial agonist) is approved for smoking cessation (Rollema et al., 2010), and naltrexone (an opioid receptor antagonist) and acamprosate (an NMDA receptor antagonist) are approved for alcohol use disorder in the United States (Franck and Jayaram-Lindström, 2013). Studies in alcohol-preferring female rats shows that varenicline reduces nicotine self-administration but has no effect on concurrent alcohol intake, and naltrexone reduces alcohol intake but has no effect on concurrent nicotine self-administration (Maggio et al., 2018; Waeiss et al., 2019), suggesting that monotherapy may be ineffective for combination alcohol and nicotine use disorder. Indeed, varenicline has shown mixed results in reducing alcohol consumption in human studies (de Bejczy et al., 2015; Litten et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2012; O’Malley et al., 2018; Plebani et al., 2013), and naltrexone and acamprosate fail to reduce cigarette smoking (Kahler et al., 2017; Fucito et al., 2012). Dual pharmacological treatment, such as combining naltrexone with nicotine replacement therapy, has been incorporated in trials to enhance the likelihood of successful alcohol and smoking abstinence (Kahler et al., 2017; Toll et al., 2010).

Pre-clinical research on combination alcohol and nicotine consumption will be necessary to understand the complex relationship between alcohol and nicotine co-use to help identify novel drug targets and strategies that may be more helpful in treating human co-use. Our mouse model can assist in the investigation of alcohol and nicotine interactions and optimization of treatment strategies, as it enables us identify how alcohol and nicotine influence co-consumption while controlling for environment, experience and genetics. Our previous work using this 3-bottle choice model showed that forced alcohol abstinence increased nicotine consumption, and resumption of alcohol access produced a compensatory increase in alcohol consumption (O’Rourke et al., 2016). In this study, we find that forced nicotine abstinence does not affect alcohol consumption, and there is no compensatory increase in nicotine consumption after nicotine access has resumed. Together, our work demonstrates that in mice, alcohol intake is unresponsive to the presence or absence of the nicotine bottle, but nicotine intake is influenced by the absence of alcohol consumption or by the adulteration of the alcohol bottle with quinine. Our data suggest that if alcohol and nicotine cessation cannot occur simultaneously, then nicotine cessation, rather than alcohol cessation, should occur first so that the increased nicotine consumption due to alcohol unavailability can be avoided. In summary, our data highlight a complex interaction between alcohol and nicotine co-consumption. Further behavioral and molecular dissection of these interactions will provide a better understanding of the neurobiology underlying alcohol and nicotine co-use.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grants T32DA007234 (MCD, JKM), F31AA026782 (JKM), R01DA034696 (KW) and R01AA026598 (AML). The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Batel P, Pessione F, Maitre C, Rueff B (1995) Relationship between alcohol and tobacco dependencies among alcoholics who smoke. Addiction 90:977–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Ericson M, Johnson DH, Engel JA, Soderpalm B (1996) Voluntary ethanol intake in the rat: effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor blockade or subchronic nicotine treatment. Eur J Pharmacol 314:257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bejczy A, Löf E, Walther L, Guterstam J, Hammarberg A, Asanovska G, Franck J, Isaksson A, Söderpalm B (2015) Varenicline for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:2189–2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBaker MC, Robinson JM, Moen JK, Wickman K, Lee AM (2019) Differential patterns of alcohol and nicotine intake: Combined alcohol and nicotine binge consumption behaviors in mice. Alcohol, doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deehan GA, Hauser SR, Waeiss RA, Knight CP, Toalston JE, Truitt WA, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA (2015) Co-administration of ethanol and nicotine: the enduring alterations in the rewarding properties of nicotine and glutamate activity within the mesocorticolimbic system of female alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:4293–4302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhofel S (2006) An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health 29:162–171 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck J, Jayaram-Lindström N (2013) Pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence: status of current treatments. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23:692–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Park A, Gulliver SB, Mattson ME, Gueorguieva RV, O’Malley SS (2012) Cigarette smoking predicts differential benefit from naltrexone for alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry 72:832–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner JL, Mingione C, Blom TJ, Anthenelli RM (2011) Smoking history, nicotine dependence, and changes in craving and mood during short-term smoking abstinence in alcohol dependent vs. control smokers. Addict Behav 36:244–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Tapper AR (2009) Modulation of ethanol drinking-in-the-dark by mecamylamine and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 204:563–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf FW, Chang SJ, Sparta DR, Bowers MS, Bonci A (2010) Motivation for alcohol becomes resistant to quinine adulteration after 3 to 4 months of intermittent alcohol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34:1565–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf FW, Lesscher HM (2014) Rodent models for compulsive alcohol intake. Alcohol 48:253–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM, Melton LJ (1996) Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. Role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA 275:1097–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa LS, Chu A, Levinson SA, Kayyali TM, DeBold JF, Miczek KA (2011) Persistent escalation of alcohol drinking in C57BL/6J mice with intermittent access to 20% ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35:1938–1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Cioe PA, Tzilos GK, Spillane NS, Leggio L, Ramsey SE, Brown RA, O’Malley SS (2017) A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Oral Naltrexone for Heavy-Drinking Smokers Seeking Smoking Cessation Treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:1201–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR (2010) Modulation of ethanol consumption by genetic and pharmacological manipulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 4:253–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Hoft NR, Cox RJ, Miyamoto JH, Ehringer MA (2012) The alpha6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit influences ethanol-induced sedation. Alcohol 46:463–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, McNamara P, Conrad M, Cao D (2009) Alcohol-induced increases in smoking behavior for nicotinized and denicotinized cigarettes in men and women. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 207:107–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Corrigall WA, Harding JW, Juzytsch W, Li TK (2000) Involvement of nicotinic receptors in alcohol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Funk D, Lo S, Coen K (2014) Operant self-administration of alcohol and nicotine in a preclinical model of co-abuse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231:4019–4029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Lo S, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Marinelli PW, Funk D (2010) Coadministration of intravenous nicotine and oral alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 208:475–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Wang A, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y (2003) Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 168:216–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Messing RO (2011) Protein kinase C epsilon modulates nicotine consumption and dopamine reward signals in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:16080–16085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Zou ME, Lim JP, Stecher J, McMahon T, Messing RO (2014) Deletion of Prkcz Increases Intermittent Ethanol Consumption in Mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:170–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Huffman CJ, O’Malley SS (2007) Alcohol history and smoking cessation in nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion sustained release and varenicline trials: a review. Alcohol Alcohol 42:196–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, McKee SA, Toll BA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cooney JL, Makuch RW, O’Malley SS (2008) Risk factors for treatment failure in smokers: relationship to alcohol use and to lifetime history of an alcohol use disorder. Nicotine Tob Res 10:1793–1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei K, Wegner SA, Yu JH, Simms JA, Hopf FW (2016) A single alcohol drinking session is sufficient to enable subsequent aversion-resistant consumption in mice. Alcohol 55:9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesscher HM, van Kerkhof LW, Vanderschuren LJ (2010) Inflexible and indifferent alcohol drinking in male mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34:1219–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, Falk DE, Johnson B, Dunn KE, Green AI, Pettinati HM, Ciraulo DA, Sarid-Segal O, Kampman K, Brunette MF, Strain EC, Tiouririne NA, Ransom J, Scott C, Stout R (2013) A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Varenicline Tartrate for Alcohol Dependence. J Addict Med 7:277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locklear LL, McDonald CG, Smith RF, Fryxell KJ (2012) Adult mice voluntarily progress to nicotine dependence in an oral self-selection assay. Neuropharmacology 63:582–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio SE, Saunders MA, Baxter TA, Nixon K, Prendergast MA, Zheng G, Crooks P, Dwoskin LP, Slack RD, Newman AH, Bell RL, Bardo MT (2018) Effects of the nicotinic agonist varenicline, nicotinic antagonist r-bPiDI, and DAT inhibitor (R)-modafinil on co-use of ethanol and nicotine in female P rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 235:1439–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks JL, Hill EM, Pomerleau CS, Mudd SA, Blow FC (1997) Nicotine dependence and withdrawal in alcoholic and nonalcoholic ever-smokers. J Subst Abuse Treat 14:521–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meliska CJ, Bartke A, McGlacken G, Jensen RA (1995) Ethanol, nicotine, amphetamine, and aspartame consumption and preferences in C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 50:619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NS, Gold MS (1998) Comorbid cigarette and alcohol addiction: epidemiology and treatment. J Addict Dis 17:55–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Teague CH, Kayser AS, Bartlett SE, Fields HL (2012) Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy-drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 223:299–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Zweben A, Fucito LM, Wu R, Piepmeier ME, Ockert DM, Bold KW, Petrakis I, Muvvala S, Jatlow P, Gueorguieva R (2018) Effect of Varenicline Combined With Medical Management on Alcohol Use Disorder With Comorbid Cigarette Smoking: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 75:129–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke KY, Touchette JC, Hartell EC, Bade EJ, Lee AM (2016) Voluntary co-consumption of alcohol and nicotine: Effects of abstinence, intermittency, and withdrawal in mice. Neuropharmacology 109:236–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plebani JG, Lynch KG, Rennert L, Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Kampman KM (2013) Results from a pilot clinical trial of varenicline for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 133:754–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MS, Broderick HJ, Drenan RM, Chester JA (2013) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing alpha6 subunits contribute to alcohol reward-related behaviours. Genes Brain Behav 12:543–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Shrikhande A, Ward KM, Tingley FD, Coe JW, O’Neill BT, Tseng E, Wang EQ, Mather RJ, Hurst RS, Williams KE, de Vries M, Cremers T, Bertrand S, Bertrand D (2010) Pre-clinical properties of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonists varenicline, cytisine and dianicline translate to clinical efficacy for nicotine dependence. Br J Pharmacol 160:334–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms JA, Steensland P, Medina B, Abernathy KE, Chandler LJ, Wise R, Bartlett SE (2008) Intermittent access to 20% ethanol induces high ethanol consumption in Long-Evans and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32:1816–1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AM, Kelly RB, Chen WJ (2002) Chronic continuous nicotine exposure during periadolescence does not increase ethanol intake during adulthood in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:976–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon EA, White RD, Radke AK (2019) Sex Differences in Binge-Like and Aversion-Resistant Alcohol Drinking in C57BL/6J Mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43:243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Hölter SM, Allingham K, Landgraf R, Zieglgänsberger W (1996) Acamprosate and alcohol: I. Effects on alcohol intake following alcohol deprivation in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 305:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Carmelli D, Cardon LR (1996) The consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and coffee in Caucasian male twins: a multivariate genetic analysis. J Subst Abuse 8:19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Carmelli D, Cardon LR (1997) Heavy consumption of cigarettes, alcohol and coffee in male twins. J Stud Alcohol 58:182–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarren JR, Bartlett SE (2017) Alcohol and nicotine interactions: pre-clinical models of dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 43:146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Cummings KM, O’Malley SS, Carlin-Menter S, McKee SA, Hyland A, Wu R, Hopkins J, Celestino P (2012) Tobacco quitlines need to assess and intervene with callers’ hazardous drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36:1653–1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, White M, Wu R, Meandzija B, Jatlow P, Makuch R, O’Malley SS (2010) Low-dose naltrexone augmentation of nicotine replacement for smoking cessation with reduced weight gain: a randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 111:200–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchette JC, Maertens JJ, Mason MM, O’Rourke KY, Lee AM (2018) The nicotinic receptor drug sazetidine-A reduces alcohol consumption in mice without affecting concurrent nicotine consumption. Neuropharmacology 133:63–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True WR, Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Eisen SA, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Tsuang M (1999) Common genetic vulnerability for nicotine and alcohol dependence in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:655–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truitt WA, Hauser SR, Deehan GA, Toalston JE, Wilden JA, Bell RL, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA (2015) Ethanol and nicotine interaction within the posterior ventral tegmental area in male and female alcohol-preferring rats: evidence of synergy and differential gene activation in the nucleus accumbens shell. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:639–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Skike CE, Maggio SE, Reynolds AR, Casey EM, Bardo MT, Dwoskin LP, Prendergast MA, Nixon K (2016) Critical needs in drug discovery for cessation of alcohol and nicotine polysubstance abuse. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 65:269–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waeiss RA, Knight CP, Hauser SR, Pratt LA, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA (2019) Therapeutic challenges for concurrent ethanol and nicotine consumption: naltrexone and varenicline fail to alter simultaneous ethanol and nicotine intake by female alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 236:1887–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]