Abstract

Purpose

To compare chromosomal aberrations and aneuploidy features in (i) blastocysts following intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and trophectoderm (TE) biopsy using preimplantation genetic screening (PGS) and (ii) early spontaneous abortion chorionic villus biopsies (SA-CVB) using single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array detection.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the data for 1014 TEs from 220 PGS cycles and 1724 SA-CVBs originating from naturally pregnant couples and patients undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) during 2017 to 2018. SNP array was applied in both PGS and SA-CVBs detection. Aberrations were defined, and the frequency and ratio of each chromosome aberration were compared between the two groups.

Results

There were more abnormalities in TEs in the form of complex chromosome aneuploidies and monosomies, while SA-CVBs had more trisomies, sex chromosome abnormalities, and polyploidies. In both groups, chromosomal aneuploidies (including monosomies and trisomies) were confined to chromosomes 14, 15, 16, 18, 21, and 22, but showed varying distributions across the groups. Aneuploidy of chromosome 22 was most frequent in TEs, whereas that of chromosome 16 predominated in SA-CVBs. Among the sex chromosome abnormalities, X monosomies were significantly more prevalent in SA-CVBs.

Conclusions

Chromosomal aberrations and aneuploidy manifested specific characteristics that differed between TEs and SA-CVBs, which indicates that distinct chromosomal abnormalities can affect certain developmental stages of embryos. Further analysis is needed to explore the chromosomal mechanisms affecting embryo development and implantation. Such information will help clinical assessments in prenatal diagnosis and reduce the incidence of genetically abnormal fetuses.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-019-01682-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aneuploidy, Blastocyst, Trophectoderm, Spontaneous abortion, Preimplantation genetic screening (PGS), Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

Introduction

Chromosomal abnormalities, also known as chromosomal dysgenesis, include numerical and structural aberrations of any chromosome. Aneuploidy is one of the most common numerical abnormalities used to define a loss or gain of the genetic material of chromosome(s) [1–3]. Chromosomal abnormalities are key causes of failed embryo development, implantation failure, and spontaneous abortion. The major types of chromosomal aneuploidy include monosomies, trisomies, polyploidies, segmental aneuploidies, and complex chromosome aneuploidies.

During a natural pregnancy, blastocysts are formed on approximately the fourth or fifth day after fertilization in preparation for adhesion to, and implantation into the endometrium. The specialized mechanism of meiosis and rapid division of early embryonic cells can easily result in chromosomal instability and aneuploidy of blastocysts, and various types of chromosomal aneuploidies can lead to discrepant embryonic development outcomes. For instance, higher survival rates have been observed in trisomic embryos than in monosomic ones from early cleavage stages, to the morula and blastocyst stages, among women aged over 36 years [4]. Implantation is a complicated process in which the blastocyst and endometrium recognize and accommodate each other. Implantation may fail for a myriad of reasons, and many of these remain unclear. However, chromosomal aneuploidies are known to be a key reason underlying implantation failure and can cause discrepant implantation outcomes. A classic example is a diploid/heterozygous chimera that defines a mixture of diploid and aneuploid cell lines within the same embryo. Mantzouratou et al. found higher rates of diploid/heterozygous chimeric embryos in women with a history of recurrent implantation failure [5]. And Spinella et al. found mosaic embryos with low aneuploidy percentages (< 50%) had higher chances of implanting and developing to term, compared with embryos that had higher mosaicism levels (> 50%) [6].

Early pregnancy failure refers to the termination of embryonic development and embryo loss. In humans, it most often occurs before 12 weeks of pregnancy. In natural conceptions that reach the stage of clinical recognition, the incidence of chromosomal aneuploidies in spontaneous abortions was about 50% [7]. Of these, abortions caused by trisomies comprised a high percentage, particularly trisomy of chromosomes 13, 16, 18, 21, and 22. Other potential factors of early pregnancy failure include compromised immunity, infections, smoking, and the use of oral contraceptives [8–10].

Most aneuploid embryos will not result in a successful implantation, however, some specific types will develop occasionally to form a clinical gestation but terminate in utero. Some are even compatible with live birth, making aneuploidy the leading cause of congenital birth defects and intellectual disability, such as 21 trisomy and 45,X0 sufferers [3]. Thus, specific types of aneuploidy appear to have different impacts on the developmental capacity of embryos. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate chromosomal abnormalities at different developmental stages.

Many technologies are available for detecting chromosome abnormalities, from classic karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), to chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), including array comparative genome hybridization (CGH), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays, and next-generation sequencing (NGS). SNP array platforms have been successfully applied in various studies to detect chromosomal anomalies in blastocysts after trophectoderm (TE) biopsy, and to test chorionic villi from aborted pregnancies (SA-CVB) [11–13]. Compared with FISH and CGH, SNP array technology allows researchers to not only recognize minor chromosomal abnormalities throughout whole chromosomes but to also detect uniparental disomy (UPD) and polyploidy (Supplemental Fig. 1). Providing a comprehensive analysis of chromosomal aneuploidies.

TEs and SA-CVBs are fairly easy to collect and analyze in the clinic. Analysis of these different fetal tissue types allows a comparison of chromosome aberrations identified before (TEs of blastocysts) and after (SA-CVBs) implantation. The aim of this study was to apply a consistent SNP array platform to TEs and SA-CVBs to identify the incidence rate of chromosomal aneuploidies before and after implantation, and to explore the mechanisms that might affect failed embryonic development and implantation.

Materials and methods

Couples underwent fertility assessment before the final embryo transfer based on the clinicians’ instruction. All couples signed a consent form and were provided with technical information that outlined the potential risks of treatment. The study was a retrospective study and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Hospital of Peking University.

PGS and blastocyst biopsy

This study involved 220 PGS cycles carried out in our center from 2017 to 2018. The indications for PGS were mainly recurrent miscarriage, abnormal childbearing history, and advanced age. The ages of the female patients ranged from 22 to 44 years (mean 33.0 ± 4.6). After ovarian stimulation cycles, embryos were fertilized via ICSI, then these embryos were cultured to the blastocyst stage on days 5 or 6 for biopsy [14]. Biopsied blastocyst cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and transferred to 0.5-mL polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tubes containing PBS for further PGS testing [14]. In total, 1014 biopsied TEs were collected for PGS. In each test, 3–5 trophectoderm blastomeres were subjected to whole genome amplification using a REPLI-g Mini Kit system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Early abortion villus collection

Early abortion chorionic villus data from 1724 samples was collected and analyzed during 2017 and 2018. The cases included both natural pregnancies and ART cycles (including plain IVF, ICSI and preimplantation genetic testing cycles). The diagnoses of early pregnancy failure was predominantly performed via ultrasound with the following diagnostic criteria applied: (1) Crown–rump length of ≥ 7 mm and no heartbeat, (2) mean sac diameter of ≥ 25 mm and no embryo, (3) absence of embryo with heartbeat ≥ 2 weeks after a scan that showed a gestational sac without a yolk sac, and (4) absence of embryo with heartbeat ≥ 11 days after a scan that showed a gestational sac with a yolk sac [15]. The ages of the female patients ranged from 20 to 46 years (mean 33.0 ± 4.5). Fresh villus tissues were suspended in PCR tubes and TIANamp Genomic DNA kits (TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, P. R. China) were used to extract DNA. All operations were performed according to instructions. The DNA concentration was estimated using a NanoQ™ spectrophotometer (CapitalBio Corp., Beijing, P. R. China).

SNP array and chromosomal aneuploidy analysis

All villus and TEs samples were subjected to aneuploid screening by SNP array on Human CytoSNP-12V2.1 chips (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Array scanning was done on HiScanSQ kits (Illumina). Data analysis was performed using GenomeStudio (standard settings) (Illumina) [16].

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (v. 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). R#3#5: Categorical data are expressed as rate (%) and χ2 tests were adopted with a test standard α = 0.05; with P < 0.05 assumed to be statistically significant.

Results

Chromosomal aberrations and aneuploidies in TEs and SA-CVBs

Mosaicisms were excluded. Among all the samples analyzed, normal embryos accounted for 60.8% and 43.3% in blastocysts and SA-CVBs, respectively. The most frequent chromosomal aberrations were mainly as follows: (1) autosomal monosomies; (2) autosomal trisomies; (3) sex chromosome abnormalities, including chromosome X monosomy (45,X0, Turner syndrome) and XXX/XYY/XXY; (4) polyploidy, comprising triploidy and tetraploidy; (5) segmental aneuploidies (SEGA); (6) UPD; and (7) complex chromosome aneuploidy (CCA), referring to more than two chromosomal aberrations or more than two types of aberration.

Comparison of abnormality types and frequencies between the two groups

In the blastocyst analysis, 1220 PGS cycles with 1014 TEs were tested, of which 617 (60.8%) were normal, and the other 397 (39.2%) were abnormal. Among the abnormal TEs, the most frequent aberrations were complex chromosome aneuploidies, trisomies, monosomies, and segmental aneuploidies, accounting for 27.9%, 27.7%, 22.2%, and 16.9%, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 1 and the comparison of the specific events among total TEs as well as SA-CVBs were shown in Supplemental Fig. 2).

Table 1.

The chromosomal aberrations frequency and ratio between TEs and early spontaneous abortion chorionic villus biopsies

| < 35 years | > = 35 years | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEs | SA-CVBs | TEs | SA-CVBs | TEs | SA-CVBs | P values | |||||||

| Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | ||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | ||

| Euploidy | 408 | 526 | 209 | 220 | 617 | 746 | |||||||

| CCAa | 51 | 22.3 | 59 | 11.1 | 60 | 35.7 | 54 | 12.1 | 111 | 27.9 | 113 | 11.5 | P < 0.001 |

| SEGAb | 50 | 21.8 | 35 | 6.6 | 17 | 10.1 | 16 | 3.6 | 67 | 16.9 | 51 | 5.2 | P < 0.001 |

| Monosomy | 47 | 20.5 | 2 | 0.4 | 41 | 24.4 | 5 | 1.1 | 88 | 22.2 | 7 | 0.7 | P < 0.001 |

| Trisomy | 63 | 27.5 | 329 | 61.8 | 47 | 28.0 | 321 | 72.0 | 110 | 27.7 | 650 | 66.5 | P < 0.001 |

| SAc | 10 | 4.4 | 54 | 10.2 | 2 | 1.2 | 24 | 5.4 | 12 | 3.0 | 78 | 8.0 | P = 0.001 |

| Polyploidy | 3 | 1.3 | 50 | 9.4 | 1 | 0.6 | 24 | 5.4 | 4 | 1.0 | 74 | 7.6 | P < 0.001 |

| UPD | 5 | 2.2 | 3 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 | 5 | 1.3 | 5 | 0.5 | P = 0.139 |

| Total | 637 | 100.0 | 1058 | 100.0 | 377 | 100.0 | 666 | 100.0 | 1014 | 100.0 | 1724 | 100.0 | |

CCAa complex chromosome aneuploidy, SEGAb segmental aneuploidy, SAc: sex chromosome abnormality

Fig. 1.

Chromosomal aberrations and aneuploidy constitutions in trophectoderm biopsies from blastocysts (TEs) and early spontaneous abortion chorionic villi (SA-CVBs). Blue bars represent data for TEs and red bars represented data for SA-CVBs. P* represents statistically significant. The distributions of complex chromosome aneuploidy (CCA), segmental aneuploidy (SEGA), monosomy (MO), trisomy (TR), sex chromosome abnormality (SA) as well as polyploidy (PO) showed significant differences between these groups, while the rates of uniparental disomy (UPD) showed no differences

In all, 1724 cases of SA-CVBs were analyzed and 746 were euploid (43.3%). The remaining 978 were identified as having chromosomal abnormalities (56.7%). Typically, trisomies accounted for two-thirds of the abnormal cases (66.5%), followed by CCA (11.5%), sex chromosome aneuploidy (8.0%) and polyploidy (7.6%). Specifically, the CCAs involved double trisomies (n = 47, 4.8%), pseudodiploids (n = 8, 0.8%), triple trisomies (n = 6, 0.6%) and others unable to be classified (n = 52, 5.3%). Polyploidies in the SA-CVBs consisted of triploidies (n = 65, 6.6%) and tetraploidies (n = 9, 0.9%).

According to χ2 testing, normal chromosome rates were significantly different between TEs and SA-CVBs: 60.8% and 43.3%, respectively (P < 0.001). Six out of the seven abnormal types displayed significant distributions across the two groups (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Specifically, CCAs were differently proportioned between blastocysts and SA-CVBs (27.9% vs 11.5%; P < 0.001), segmental aneuploidies (16.9% vs 5.2%; P < 0.001) and monosomies (22.2% vs 0.7%; P < 0.001). Converse proportions were also seen for trisomies (27.7% vs 66.5%; P < 0.001), sex chromosome abnormalities (3.0% vs 8.0%; P = 0.001) and polyploidies (1.0% vs 7.6%; P < 0.001). Whereas, the constituent ratio of UPDs showed no significant difference between the two groups (1.3% vs 0.5%). Noticeably, CCAs, monosomies and segmental aneuploidies (in declining order) were lower in the SA-CVBs than in the TEs groups. Conversely, trisomies, sex chromosome abnormalities and polyploidies (in declining order) were more frequent in the SA-CVBs group. Most notably, trisomies accounted for 66.5%, and the proportion of trisomies rose to 72.0%, with a maternal age over 35 years (Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 3).

Analysis of individual chromosomal aneuploidy rates between the two groups

Besides the specific aneuploid types, we focused on individual chromosomes, and analyzed specific aberrations. Numerical abnormalities in chromosomes, mainly monosomies and trisomies were further assessed.

In terms of autosomes, the frequencies and ratios of monosomies and trisomies per autosome are listed in Table 2. For TEs, there were 44.4% monosomies and 55.6% trisomies, and the most frequent aneuploid chromosomes involved numbers 22, 16, 21, 18, and 14 (in declining order). For SA-CVBs, there were 1.1% monosomies and 98.9% trisomy, and the most frequent aneuploid chromosomes were numbers 16, 22, 21, 15, and 14. Clearly, these orders differed when comparing TEs with SA-CVBs (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Table 2.

Individual chromosomal aneuploidy of TEs and early spontaneous abortion chorionic villus biopsies

| TEs | SA-CVBs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | Monosomy | Trisomy | Combined | Monosomy | Trisomy | Combined | ||||||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 1 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.7 | 3 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 2.3 | 15 | 2.1 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.7 | 11 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 5 | 5.4 | 1 | 0.9 | 6 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 2.5 | 16 | 2.2 |

| 5 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.8 |

| 6 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.8 |

| 7 | 2 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 3.5 | 23 | 3.2 |

| 8 | 2 | 2.2 | 2 | 1.7 | 4 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 3.7 | 24 | 3.3 |

| 9 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 3.4 | 4 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 3.7 | 24 | 3.3 |

| 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 1.8 | 12 | 1.7 |

| 11 | 1 | 1.1 | 3 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.7 |

| 12 | 1 | 1.1 | 3 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.8 |

| 13 | 3 | 3.3 | 4 | 3.4 | 7 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 3.7 | 24 | 3.3 |

| 14 | 6 | 6.5 | 7 | 6.0 | 13 | 6.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 3.1 | 20 | 2.7 |

| 15 | 2 | 2.2 | 7 | 6.0 | 9 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 53 | 8.1 | 53 | 7.3 |

| 16 | 11 | 12.0 | 18 | 15.4 | 29 | 13.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 186 | 28.5 | 186 | 25.5 |

| 17 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.6 | 3 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.2 | 8 | 1.1 |

| 18 | 8 | 8.7 | 5 | 4.3 | 13 | 6.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 17 | 2.6 | 17 | 2.3 |

| 19 | 3 | 3.3 | 7 | 6.0 | 10 | 4.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.3 |

| 20 | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 3.4 | 5 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.5 | 10 | 1.4 |

| 21 | 11 | 12.0 | 14 | 12.0 | 25 | 12.0 | 7 | 9.1 | 47 | 7.2 | 54 | 7.4 |

| 22 | 29 | 31.5 | 23 | 19.7 | 52 | 24.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 135 | 20.7 | 135 | 18.5 |

| X/Y | 4 | 4.4 | 7 | 6.0 | 11 | 5.3 | 70 | 90.9 | 2 | 0.3 | 72 | 9.9 |

| Total | 92 | 117 | 209 | 77 | 652 | 729 | ||||||

Fig. 2.

Trisomy and monosomy features in trophectoderm biopsies from blastocysts (TEs) and early spontaneous abortion chorionic villi (SA-CVBs). Blue bars in A–C represent data for TEs, while red bars represent data for SA-CVBs. A shows the constitution of chromosomal trisomies (%), B shows monosomies (%), while C shows the distributions of individual chromosomes (%)

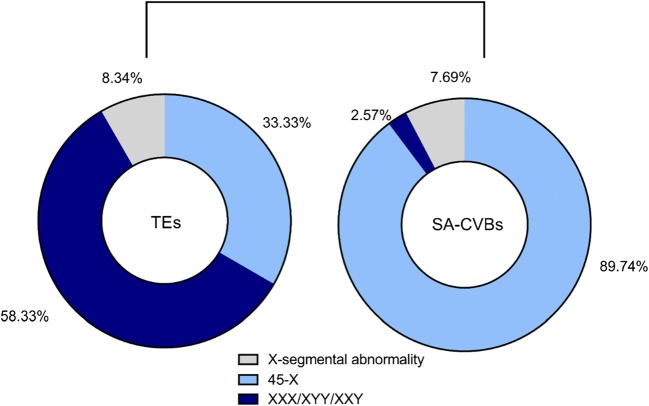

In terms of sex chromosomes, the constituent abnormalities showed different characteristics in the TEs and SA-CVBs groups. Sex chromosome abnormalities were discovered in both groups, including 45,X0, 47,XXX/XYY, and X-segmental abnormalities. However, in TEs, trisomy was the primary aberration, while in SA-CVBs, X monosomy (45,X0) accounted for nearly 90% of the abnormalities (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Sex chromosome abnormalities in trophectoderm biopsies from blastocysts (TEs) and early spontaneous abortion chorionic villi (SA-CVBs)

Segmental aberrations of chromosomes in TEs and SA-CVBs

In the analysis of blastocysts, segment occurred mainly in chromosomes 8, 5, 7, and 4, which together totaled 45.3%. Additionally, in SA-CVBs, segmental aberrations were predominantly found in chromosomes 18 and 16 (27.5% in total), followed by chromosomes 8, 5, 7, and 4 in a similar trend to that seen in TEs (Fig. 4A). We also separated segmental aneuploidies based on whether duplications or deletions of chromosomal materials occurred. TEs showed more losses than gains (deletions 48, 71.6%; duplications 19, 28.4%; deletion/duplication ratio 2.50; Fig. 4B). Conversely, duplications were more frequent than deletions in SA-CVBs (deletions 25, 49.0%; duplications: 26, 51%; deletion/duplication ratio: 0.96; Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Segmental aberrations of chromosomes in trophectoderm biopsies from blastocysts (TEs) and SA-CVBs. A shows the sum constituent of segmental aberrations of each chromosome, with blue bars representing data for TEs and red bars for SA-CVBs. B and C show deletion and duplication ratios of segmental aberrations in TEs and SA-CVBs, respectively

Types of CCAs in TEs and SA-CVBs

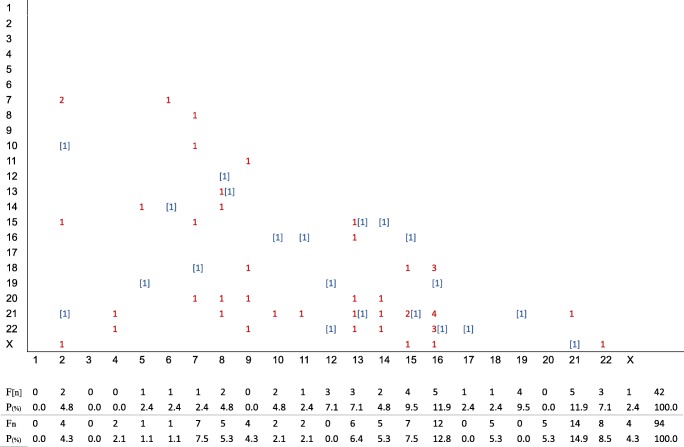

Among TEs, CCAs constituted double trisomies (n = 21, 5.3%), triple trisomies (n = 6, 1.5%), pseudodiploids (n = 23, 5.8%), double monosomies (n = 10, 2.5%), triple monosomies (n = 2, 0.5%), and others unable to be classified (n = 49, 12.3%). Among these subgroups, double trisomies were analyzed in more detail, accounting for 5.3% (21/397) and 4.8% (47/978) in TEs and SA-CVBs respectively. In the TEs, double trisomies did not display any particular distribution, with trisomy 16 being slightly more frequent than in the other chromosomes. In the SA-CVBs, higher double trisomy rates were seen in chromosomes 16 and 21 (Fig. 5). Compared with single trisomies, we found similar trends for chromosomes 16 and 21, while we failed to find any peak of double trisomies in chromosome 22.

Fig. 5.

Frequency and distribution of double trisomy in trophectoderm biopsies from blastocysts (TEs) and SA-CVBs. *[n]: double trisomy in TEs, n: double trisomy in SA-CVBs. Both abscissa and ordinate represent chromosomes. F[n] and Fn independently represent frequencies of double trisomy in TEs and SA-CVBs, while P(%) shows the proportions of double trisomy in these two groups

Discussion

Although it is widely accepted that chromosomal aneuploidies are the most significant causes of implantation failure and spontaneous abortion in human reproduction, little is known about the characteristics of aneuploidies during the time from the blastocyst stage to early implantation, and the ultimate fate of such abnormal embryos [17, 18]. We investigated the spectrum of chromosomal abnormalities in blastocysts (after TE biopsy and PGS) and SA-CVBs to better understand the correlation of aneuploidy variations before and after implantation. Our results show specific chromosomal spectra, in terms of aberrant types and individual chromosome features, occur in blastocyst biopsies and SA-CVBs.

Aberrations and aneuploidy

Trisomies and Monosomies

The most notable characteristic change occurring from TEs to SA-CVBs was an increased rate of trisomy and a reduced rate of monosomy. For autosomes, the incidence of monosomies in the SA-CVBs group decreased by 30-fold compared with that in TEs (0.7% vs 22.2%). To better present this trend, and avoid influences from sample variations, we compared the ratio of gain to loss chromosomally. The ratio was 1.25 (27.7/22.1%) in TEs, similar to the 1.13 ratio reported previously [19]. However, this index increased dramatically to 92.3 (66.5/0.7%) in SA-CVBs. This result shows the detrimental nature of monosomies for successful implantation. In the TEs group, autosomal monosomies were most frequently found in chromosomes 22, 21, 16, 18, and 14. Remarkably, these were overwhelmingly concentrated on chromosome 21 in the SA-CVBs group. This finding is consistent with previous studies on early pregnancy loss [19, 20]. Presumably, each autosomal chromosome—possessing a large number of functional genes—plays a vital role in early embryo survival and growth. Any missing genetic material could have a global effect on developmental pathways involving genes that reside on both monosomic and non-monosomic chromosomes and contribute to massive methylation, transcriptomal and proteomic changes, which finally leads to blastocyst death [21]. Additional indirect evidence of monosomic lethality is that, unlike those born with 21 trisomy, neonates with chromosome 21 monosomies are rare, with most exhibiting mosaicism. Moreover, these neonates are extremely vulnerable and will die before adolescence [22]. In contrast, autosomal trisomies predominated among aneuploidies when comparing TEs and SA-CVBs (27.7% vs 66.5%). We surmise that gaining a chromosome has comparatively less impact on implantation than losing a chromosome and the duplication of some genes might benefit implantation to some extent [23]. For instance, Chou et al. used in vitro and mouse transplantation assays to study hematopoiesis in trisomy 21 fetal livers. Remarkably, trisomy 21 progenitors exhibited enhanced production of erythroid and megakaryocytic cells [24]. Thus, this particular trisomy is not fatal at the blastocyst stage and the embryo/fetus can continue to grow.

Interestingly, autosomal trisomies in the TEs group were most frequently found in chromosomes 22, 16, 21, and 15 (in declining order). This result is consistent with some previous studies [4, 25] while others ranked TEs trisomy rates in the order of 22, 16, 15, and 21 [19, 26]. However, it seems that chromosome 22 is the most liable to trisomy at the blastocyst stage. Similarly, autosomal trisomies in spontaneous abortions have been investigated intensively for many years, and many reports have suggested that trisomy 16 was the most common aneuploidy to be found [19, 20, 27, 28]. This was supported by our results in the SA-CVB group, autosomal trisomies were found most frequently in chromosomes 16, 22, 15, and 21 (in declining order). As an indicator of chromosome stabilization, the results for individual chromosomal abnormalities (a combination of monosomy and trisomy) also demonstrated a reducing rate from chromosomes 22 to 16. It appeared that blastocysts carrying a trisomy 22 karyotype may be capable of passing through early development to implantation. Moreover, from the cleavage stage to the blastocyst stage, it was reported that embryos with trisomy 22 had higher developmental rates than those with trisomy 16 (57.6% vs 54.0%) [4] and, in the SA-CVB samples, more trisomy 16 were detected in spontaneous abortions [29, 30]. And it was estimated that the stillbirth rate of embryos carrying trisomy 22 was approximately 0.2% [31]. Therefore, although chromosome 22 is the shortest autosome in length, the aneuploidy of it deserves further attention since trisomy 22 blastocysts were predominated and more likely to be successfully implanted, even bringing about stillbirth.

Complex chromosome abnormalities

Here, we defined CCAs as being the presence of two or more chromosomal aberrations or two or more types of chromosomal aberrations. For further analysis, CCAs were categorized into double monosomies, double trisomies, triple monosomies, triple trisomies, pseudodiploidies, and others that could not be classified. These cytogenetic abnormalities will not show up in normal human cells but they can be detected in cancer cells, for example in cases of acute leukemia. Double monosomies (such as 44,XN,-8,-21) and triple monosomies (such as 43,XN,-18,-21,-22) can be lethal, precluding the establishment of a viable pregnancy. No clinical case of a double monosomy or triple monosomy growing to post-conceptual age has been reported. Additionally, no studies have yet addressed the incidence of double or triple monosomies in blastocysts. Here we report overall incidences of 1% (10/1014) and 0.2% (2/1014), respectively. In our study, double trisomies (such as 48,XN,+13,+21) were categorized as CCAs. Given that the overall rate of double trisomies had no statistical difference between the two groups (5.3% vs 4.8%), we suspect that this form of CCA had a greater effect on spontaneous abortion than implantation. Previously, no involvement of either chromosomes 1 or 19 in a double trisomy event could be found [32]. In our SA-CVBs data, we also did not detect chromosomes 1 or 19 in a double trisomy. Nevertheless, we discovered four double trisomy events affecting chromosome 19 in the blastocyst group, karyotyping as 48,XN,+5,+19; 48,XN,+19,+21; 48,XN,+12,+19; and 48,XN,+16,+19. It is known that chromosome 19 is the most gene-dense region in the human genome and that chromosome 1 carries the greatest number of genes. Thus, a double trisomy of chromosome 19 and 1 appears to be fatal for embryonic development.

Segmental aneuploidies

The proportion of segmental aneuploidy was higher in TEs than in SA-CVBs samples (16.9% vs 5.2%). It is difficult to define such abnormalities in terms of fatal or non-fatal outcomes because they include gains or losses of parts of chromosomes involving no particular segment or size. Figure 4 illustrates that chromosomal segmental abnormalities in TEs were mainly concentrated on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8, which is consistent with a previous study [26]. Meanwhile, segmental abnormalities in SA-CVBs were concentrated on chromosomes 16 and 18. Chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8 are longer and carry more genes, or gene fragments, than chromosomes 16 and 18. It is possible that larger chromosomes are more susceptible to partial losses/gains, which leads to blastocyst death when key genes for embryonic development are located in the affected segment [33]. Additionally, the ratio of deletions to duplications was significantly higher in TEs than in SA-CVBs, at 2.50 vs 0.96 respectively. This result also confirmed our initial assumption that gene losses would be fatal for normal development. Furthermore, it was observed that deletions were predominant with a maternal age under 35 years in TEs group (P = 0.043), but the result was considered to be related to the small sample size (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Polyploidy

The polyploidy rates displayed increased trends similar to sex chromosome errors between the two groups we studied. Overall, polyploidies are rarely observed in humans. Triploidy has been identified in 1%–3% of human pregnancies and in 15% of spontaneous abortions [34]; tetraploidy, however, has only been observed in 1%–2% of early spontaneous abortions [35]. In our study, only four triploidy events were detected out of 1014 TEs (0.4%). We surmise that this low incidence arose from the application of intracytoplasmic sperm injection technology and sperm and oocyte selection. In preparing spermatozoa for ICSI, embryologists select high-quality gametes using a “swim-up” method, density gradient centrifugation, migration–sedimentation or glass wool filtration. While such rigorous artificial selection of spermatozoa for good morphology and vitality cannot eliminate the use of genetically abnormal spermatozoa completely, the technology makes it less likely. Meanwhile, the ICSI procedure also involves the selection of good morphology oocytes to a certain extent. This process could be effective in ruling out dispermy, which is one cause of polyploidy during natural fertilization.

Sex chromosome abnormalities

For the sex chromosomes, the error rate was significantly lower in TEs according to χ2 tests, and tended upwards after implantation. In cases of X/Y abnormalities, cytogenetic X0 occurred the most frequently. Turner syndrome was the most common monosomy disease. Affected individuals are able to survive for years, and the incidence of this anomaly, diagnosed following clinical ascertainment, has been estimated to be at least 22.2 per 100,000, with more than 50% having an apparent 45,X0 karyotype [36]. Because Turner syndrome is not fatal, in theory, the detection rate should have been higher or similar in TEs than in SA-CVBs but this was not found in our study. We suspect that this outcome was also associated with the application of ICSI whereby artificial selection methods were able to partially reduce the use of abnormal gametes. However, the specific mechanism is not clear and might be related to the different sources that SA-CVBs samples were recruited from, both natural pregnancies and ART cycles, while all blastocysts were collected from PGS cycles.

Aneuploidy and final fate

As discussed above, various chromosomal error types showed distinct outcomes, and CCAs and segmental aneuploidies were fatal in blastocysts, arresting embryo growth. Individual chromosomal abnormalities in chromosome 1 and 19 also have great impacts on blastocyst development (Supplemental Fig. 5). After implantation (that is, in the SA-CVB samples) most abnormalities were trisomies. Besides, sex chromosomal abnormalities will mainly present in early stages after implantation. Therefore, we surmise that polyploid blastocysts might be able to grow and implant, but arrest thereafter.

Limitations

Generally, the ideal specimen for exploring aneuploidy fatal differences should be naturally fertilized human embryos whose development process is not disturbed in the normal population. However, due to the unavailability of this normal cohort in early embryo development stage, the vast amount of data we can actually obtain can only be derived from PGS, which cannot reveal the absolutely true aneuploid percentage. Thus, we performed a comparative distribution analysis in aberration types, and specific chromosomes to reflect the relative lethality effect.

Besides, ICSI process could affect the aneuploidy composition. PGS samples were obtained from infertile patients after the use of ICSI. The ICSI procedure itself could decrease the occurrence of polyploidy and sex chromosome abnormalities. Also, only about 3–5 blastomeres were separated from the TE of blastocysts, instead of endotrophic cells, which are the blastocyst components that develop into the embryo proper. In addition, the small number of cells collected could have limited our ability to detect mosaicism in these embryos. Therefore, our data can partly explain the embryos’ chromosomal status but cannot be considered equally as the embryos develop at day 5 or 6.

The aborted materials we sampled were from patients undergoing natural or ART-generated pregnancies (including plain IVF, ICSI and PGT cycles). In practice, the samples were trophoblastic villus cells, not endotrophic cells, implying an indirect assessment of embryo development after implantation. Clinically, only aborted samples were collected, and it is impossible to detect embryonic chromosomes in natural pregnancies. This could have affected our estimation of the proportions of abnormal and normal embryos.

In conclusion, this large and comprehensive study compared chromosomal aberrations and types of aneuploidy in biopsies from presumably normal blastocysts subjected to PGS and chorionic villi from early spontaneous abortions and further analyzed the possible influence of embryonic chromosomal constitutions on embryonic development stages. We have summarized chromosomal abnormalities and individual chromosomes that were lethal to embryonic development in the SA-CVB samples. Some of these can be eliminated naturally through embryonic arrest at early stages (such as double monosomies), but some can progress to early pregnancy stages (such as trisomies). In view of these findings, we recommend that blastocyst PGS should be offered to women undergoing ART with a high risk of chromosomal abnormalities, to select viable embryos with higher implantation ability, decreased likelihood of spontaneous abortion, and a lower risk of genetic abnormalities in offspring.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 1573 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)

Funding information

This study was supported by 2018YFC1003104 “National Key R&D Program of China” and BYSY2018015 “Clinical Key Program of Peking University Third Hospital”.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lejeune J, Gautier M, Turpin R. Study of somatic chromosomes from 9 mongoloid children. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1959;248(11):1721–1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs PA, Baikie AG, Court BW, Strong JA. The somatic chromosomes in mongolism. Lancet. 1959;1(7075):710. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(59)91892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez PJ, Lee J, Whitehouse M, Moschini RM, Knopman J, Duke M, et al. Embryo selection versus natural selection: how do outcomes of comprehensive chromosome screening of blastocysts compare with the analysis of products of conception from early pregnancy loss (dilation and curettage) among an assisted reproductive technology population? Fertil Steril. 2015;104(6):1460–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubio C, Rodrigo L, Mercader A, Mateu E, Buendia P, Pehlivan T, et al. Impact of chromosomal abnormalities on preimplantation embryo development. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27(8):748–756. doi: 10.1002/pd.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantzouratou A, Mania A, Fragouli E, Xanthopoulou L, Tashkandi S, Fordham K, et al. Variable aneuploidy mechanisms in embryos from couples with poor reproductive histories undergoing preimplantation genetic screening. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(7):1844–1853. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinella F, Fiorentino F, Biricik A, Bono S, Ruberti A, Cotronea E, et al. Extent of chromosomal mosaicism influences the clinical outcome of in vitro fertilization treatments. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capalbo A, Hoffmann ER, Cimadomo D, Ubaldi FM, Rienzi L. Human female meiosis revised: new insights into the mechanisms of chromosome segregation and aneuploidies from advanced genomics and time-lapse imaging. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(6):706–722. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo LY, Zhai M, Wang SS, Zhang Y. Meta-analysis of risk factors related to the induction of embryo damage. CJCHC FEB. 2016;24(2):166–169. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christianson RE, Sherman SL, Torfs CP. Maternal meiosis II nondisjunction in trisomy 21 is associated with maternal low socioeconomic status. Genet Med. 2004;6(6):487–494. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000144017.39690.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter JE, Allen EG, Shin M, Bean LJ, Correa A, Druschel C, et al. The association of low socioeconomic status and the risk of having a child with down syndrome: a report from the National Down Syndrome Project. Genet Med. 2013;15(9):698–705. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chris MJ, Servi JC, Joseph CD, Marion D, Hubert JS, Bertien HC, Christine EM, et al. SNP array-based copy number and genotype analyses for preimplantation genetic diagnosis of human unbalanced translocations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(9):938–944. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elias MD, Jacques B, François A, Douglas W, Jo-Ann B, Carla C, et al. Technical update: preimplantation genetic diagnosis and screening. J Obstet Gynaecol Can2015;37(5):451–463. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Wang Y, Cheng Q, Meng L, Luo C, Hu H, Zhang J, Cheng J, Xu T, Jiang T, Liang D, Hu P, Xu Z. Clinical application of SNP array analysis in first-trimester pregnancy loss: a prospective study. Clin Genet. 2017;91(6):849–858. doi: 10.1111/cge.12926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Li R, Lian Y, Chen L, Shi X, Qiao J, Liu P. Vitrified/warmed single blastocyst transfer in preimplantation genetic diagnosis/preimplantation genetic screening cycles. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(11):21605–21610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, Blaivas M. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1443–1451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1302417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J, Zhao N, Wang X, Qiao J, Liu P. Chromosomal characteristics at cleavage and blastocyst stages from the same embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32(5):781–787. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0450-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taranissi M, El-Toukhy T, Gorgy A. Influence of maternal age on the outcome of PGD for aneuploidy screening in patients with recurrent implantation failure. Reprod BioMed Online. 2005;10(5):628–632. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Findikli N, Kahraman S, Saglam Y, Beyazyurek C, Sertyel S, Karlikaya G, Karagozoglu H, Aygun B. Embryo aneuploidy screening for repeated implantation failure and unexplained recurrent miscarriage. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;13(1):38–46. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fragouli E, Alfarawati S, Spath K, Jaroudi S, Sarasa J, Enciso M, Wells D. The origin and impact of embryonic aneuploidy. Hum Genet. 2013;132(9):1001–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai XY, Zhou L, Xie JS. Chromosome abnormality analysis of 7036 chorionic villi in spontaneous miscarriage cases by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Chin J Lab Med. 2017;40(8):598–601. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCallie BR, Parks JC, Patton AL, Griffin DK, Schoolcraft WB, Katz-Jaffe MG, et al. Hypomethylation and genetic instability in monosomy blastocysts may contribute to decreased implantation potential. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e159507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halloran KH, Breg WR. Mahoney MJ.21 monosomy in a retarded female infant. J Med Genet. 1974;11(4):386–389. doi: 10.1136/jmg.11.4.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Licciardi F, Lhakhang T, Kramer YG, Zhang Y, Heguy A, Tsirigos A. Human blastocysts of normal and abnormal karyotypes display distinct transcriptome profiles. Nature. 2018;8(1):14906. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33279-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou ST, Opalinska JB, Yao Y, Fernandes MA, Kalota A, Brooks JS, Choi JK, Gewirtz AM, Danet-Desnoyers GA, Nemiroff RL, Weiss MJ. Trisomy 21 enhances human fetal erythro-megakaryocytic development. BLOOD. 2008;112(12):4503–4506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munne S, Bahce M, Sandalinas M, Escudero T, Marquez C, Velilla E, et al. Differences in chromosome susceptibility to aneuploidy and survival to first trimester. Reprod BioMed Online. 2004;8(1):81–90. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fragouli E, Wells D. Aneuploidy in the human blastocyst. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;133(2–4):149–159. doi: 10.1159/000323500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassold T, Chen N, Funkhouser J, Jooss T, Manuel B, Matsuura J, Matsuyama A, Wilson C, Yamane JA, Jacobs PA. A cytogenetic study of 1000 spontaneous abortions. Ann Hum Genet. 1980;44(2):151–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1980.tb00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du Y, Chen L, Lin J, Zhu J, Zhang N, Qiu X, et al. Chromosomal karyotype in chorionic villi of recurrent spontaneous abortion patients. Biosci Trends. 2018;12(1):32–39. doi: 10.5582/bst.2017.01296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emanuel BS, Zackai EH, Aronson MM, Mellman WJ, Moorhead PS. Abnormal chromosome 22 and recurrence of trisomy-22 syndrome. J Med Genet. 1976;13(6):501–506. doi: 10.1136/jmg.13.6.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall HE, Surti U, Hoffner L, Shirley S, Feingold E, Hassold T. The origin of trisomy 22: evidence for acrocentric chromosome-specific patterns of nondisjunction. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2249–2255. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassold TJ, Jacobs PA. Trisomy in man. Annu Rev Genet. 1984;18:69–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.18.120184.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micale M, Insko J, Ebrahim SA, Adeyinka A, Runke C, Van Dyke DL. Double trisomy revisited--a multicenter experience. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30(2):173–176. doi: 10.1002/pd.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babariya D, Fragouli E, Alfarawati S, Spath K, Wells D. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(12):2549–2560. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McWeeney DT, Munne S, Miller RC, Cekleniak NA, Contag SA, Wax JR, et al. Pregnancy complicated by triploidy: a comparison of the three karyotypes. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(9):641–645. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundvall L, Lund H, Niemann I, Jensen UB, Bolund L, Sunde L. Tetraploidy in hydatidiform moles. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):2010–2020. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathur A, Stekol L, Schatz D, NK ML, Scott ML, Lippe B. The parental origin of the single X chromosome in Turner syndrome: lack of correlation with parental age or clinical phenotype. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48(4):682–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 1573 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)