Abstract

Limb salvage surgery refers to orthopaedic procedures designed to resect tumors and reconstruct limbs. Improvements in managing malignant bone lesions have led to a dramatic shift in limb salvage procedures. Orthopaedic surgeons now employ four main reconstructive procedures: endoprosthesis, autograft, bulk allograft, and allograft prosthetic composite. While each approach has its advantages, each technique is associated with complications. Furthermore, knowledge of procedure specific imaging findings can lead to earlier complication diagnosis and improved clinical outcomes. The aim of this article is to review leading reconstructive options available for limb salvage surgery and present a case series illustrating the associated complications.

Keywords: Limb salvage, Endoprosthesis, Autograft, Allograft

1. Introduction

Prior to the 1970s, amputation was the mainstay of treatment for primary malignant bone tumors such as osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma and chondrosarcoma.1,2 Due to the aggressive nature of these tumors, amputation provided patients with the best possible clinical and functional outcomes; however, amputation is a morbid procedure and was associated with 5-year survival rates of around 10–20%.2,3 Despite surgical amputation of the limb, 80% of patients would still die from metastatic disease to the lungs.1

Advances in adjuvant therapies, reconstructive surgical techniques, and incorporation of a multidisciplinary approach led to a shift in treatment paradigms that focused on limb salvage procedures.2 Today, 90% of patients with malignant bone tumors involving the extremity are successfully treated with limb salvage procedures as opposed to amputation.4 Five-year survival rates have increased to 66–82%, with notable improvements in function and patient-reported outcomes compared to amputation.3,5

The four main limb salvage procedures include endoprosthesis, autograft, bulk allograft, and allograft prosthetic composite reconstructions. Familiarity with these reconstructive options and the ability to recognize potential complications in the post-operative period is essential for both radiologists and Orthopaedic surgeons. The aim of this article is to highlight leading reconstructive options available for limb salvage surgery and to present a case series illustrating their main associated complications.

2. Choosing a reconstructive technique

Despite advancements in limb salvage surgery, relative contraindications remain, including tumor involvement of major neurovascular structures, pathologic fractures violating compartment boundaries, infection of the surgical field, and extensive muscle and soft-tissue involvement that compromises limb function or precludes wound closure. Consequently, the necessity for patients to be appropriately staged and assessed through a multidisciplinary approach prior to consideration of limb preservation should not be understated.2

Four principles guide the clinical application of limb salvage surgery in the treatment of malignant bone tumors: local disease recurrence risk should not be greater and survival rates should not be worse than amputation, procedure complications should not delay adjuvant chemotherapy, reconstruction increases risk of major complications resulting in secondary procedures and frequent hospitalizations, and limb function exceeds that of amputation.2,6 A summary of the different techniques can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Reconstructive Techniques

| Techniques | Endoprosthesis | Autograft | Bulk Allograft | Allograft Prosthetic Composite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indications |

|

Preferred Method if no contraindications | Large defects not amendable to prosthetic reconstruction | Tendon Reconstruction options including extensor mechanism, rotator cuff, and abductors in the hip |

| Contraindications |

|

|||

| Complications | Hardware associated complications:2

|

|

|

|

| Evaluation |

|

Graft-host fusion is demonstrated by the appearance of a radiodense line on the endosteal border of the autograft-allograft interface9 | Plain radiography shows a periprosthetic zone of radiolucency and periosteal reaction in presence of infection36 | lucent line at the junctional cortex after 9 months, along with cortices that are not entirely united is concerning for non-union27 |

3. Imaging techniques

3.1. Radiographs

The standard imaging method for short and long-term postoperative evaluation in limb salvage surgery is plain radiographs. Radiographs are valuable post-operatively to determine the position of the prosthetic components or allograft reconstruction. Specifically, they provide an evaluation for multiple modes of failure, including prosthetic loosening, allograft resorption, mechanical failure and per-prosthetic/graft fractures.7 They provide characterization of soft tissue and osseous mineralization, illustrating the bone contour and structure which may identify recurrence in patients with bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Hence, radiographs provide a valuable comparison study to provide an initial view of possible complications or recurrence, which can be validated with additional Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) findings.8

3.2. Computed Tomography

CT provides further characterization of suspected postoperative complications. While metallic hardware can cause severe streak artifacts due to photon starvation and beam hardening artifact, recent advances in metal-reduction imaging techniques significantly improve visualization of native and allograft bone, bone-metal interfaces, and adjacent soft tissues.9 Consequently, metal reduction CT allows for accurate assessment of metal hardware and detection of complications, including non-union, hardware failure, infection, aseptic loosening and periprosthetic fractures. This may be achieved by adjusting several parameters to reduce the degree of metallic-hardware related artifact, such as a higher peak voltage and tube charge, narrow collimation, thick section and soft tissue/smooth kernel reconstruction and extended CT scale.8 Multiplanar reformation and 3D imaging can also be used to provide a comprehensive view of the hardware in relation to the host bone or graft reconstruction, allowing for analysis of complex cases that can further guide surgical management if there is need for revision.9

Add reference for 3D [Ritacco, Lucas & Mosquera, Candelaria & Albergo, Ignacio & Muscolo, Domingo & Farfalli, German & Ayerza, Miguel & Aponte-Tinao, Luis & Mancino, Axel. (2018). Three-Dimensional Printing and Navigation in Bone Tumor Resection. 10.5772/intechopen.79249.]

3.3. Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography

Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (PET/CT) is a nuclear medicine imaging modality effective in the evaluation of regional tumor recurrence, distant metastasis and treatment response. The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria emphasizes its utility in cases in which MRI and CT are equivocal.10 For instance, it may not be possible to discriminate between post-therapeutic changes and tumor recurrence with CT and MRI, since artifacts may impair effective visualization. In these circumstances, PET/CT has a higher diagnostic accuracy than CT alone and can be complementary to MRI.10 Nevertheless, limitations include the lack of IV contrast to improve soft tissue mass or fluid collection conspicuity, and the non-specificity of radiotracer uptake in both neoplastic and inflammatory lesions. Furthermore, artifact reduction methods may falsely elevate radiotracer uptake, confounding detection of local tumor recurrence.9,10

3.4. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Due to its superior soft tissue contrast resolution, conventional MRI offers complementary information to plain radiographs.11 In cases involving neurovascular and marrow involvement, MRI is particularly invaluable in surgical planning, with reliable accuracy when assessing for neurovascular encasement by the tumor.12 During the post-operative period, differentiation must be made between post-surgical soft tissue changes and tumor recurrence, which is particularly difficult in cases involving adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation. Additionally, metallic artifacts in MRI remain a significant problem, specifically in-plane distortion, poor fat suppression, geometric distortion and through-section distortion.13 Methods to reduce metallic artifacts include fast spin-echo sequences, short time inversion recovery (STIR) sequences for fat suppression, a high bandwidth, thin section selection and increased matrix.13, 14, 15

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is an MRI technique capable of measuring microscopic movements of water molecules within tissues, allowing for differentiation from extracellular space. In particular tumor entities, including osteosarcomas, treatment success is not always correlated with radiographic decrease in tumor diameter, as neoadjuvant therapy may promote matrix mineralization and, paradoxically, enhance tumor conspicuity; moreover, treatment may result in intratumoral hemorrhage, leading to decreased tumor enhancement but little change in tumor dimension.16 DWI constitutes a noninvasive biomarker for treatment response by illustrating necrotic regions within a tumor.16 Hence, DWI is a useful modality to monitor tumor response to chemotherapy and radiation treatment.11 In the post-operative setting, functional MRI sequences including DWI and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI have been shown to improve specificity in discrimination of tumor recurrence from inflammatory change in the surgical bed.17

4. Reconstructive options

4.1. Endoprosthesis

Endoprosthetic implants are one option available for limb reconstruction following large tumor resections. In particular, they are utilized in reconstruction of periarticular and metaphyseal defects following resection of primary/secondary tumors and in cases of failed allografts. Endoprostheses are made from metallic alloys and are readily available in a varied range of sizes and modular pieces, which allows the implant to match the defect in the bone and adjacent joint, as demonstrated in Fig. 1. In cemented models, immediate weight bearing is allowed, providing improved functionality and patient satisfaction.18 On the contrary, in some cases of press-fit or uncemented prostheses, restrictions in weight-bearing may be implemented to allow for reliable healing and to minimize cases of aseptic loosening.18 This is due to uncemented models' reliance on biologic fixation via the implant's porous coating in order to obtain bone ingrowth.

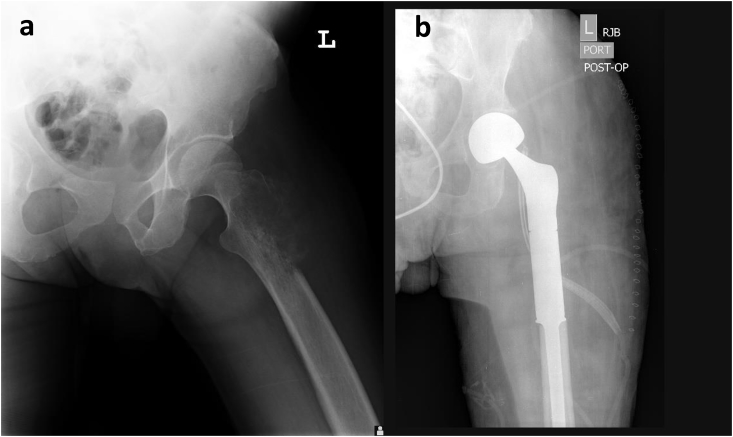

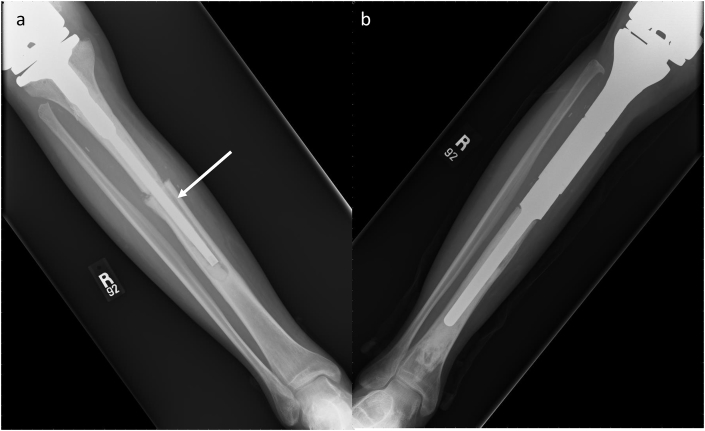

Fig. 1.

(a and b) Proximal Femoral Endoprosthesis. A patient with pathology-confirmed osteosarcoma. (a) Frontal radiographic view of the left pelvis demonstrates lytic lesion (white arrow) involving lateral aspect of the proximal left femur with associated aggressive periosteal reaction. (b) Post-operative radiograph reveals intact femoral endoprosthesis in proper alignment with preservation of native acetabulum.

Though the flexibility and availability of prosthetic implants make them an attractive reconstructive option, complication rates are high and overall failure rates approach 25%.7 The five primary modes of complication were classified by Henderson et al. as soft-tissue failures (Type 1), aseptic loosening (Type 2), structural failures (Type 3), infection (Type 4) and tumor progression (Type 5).7 Review of prosthetic reconstruction images should be performed with the understanding that the survival of endoprosthesis is highly dependent on its anatomic location. For instance, total femur replacements have the lowest 5-year survival rate at 48%, followed by proximal tibial reconstructions at 54%, distal femur at 59% and proximal femur at 88%.2,19 Furthermore, while endoprosthesis provides a shorter operation time, hospital stay and rapid weight-bearing status for patients, biological options including allograft and autograft offer improved integration with decreased risk of hardware-associated complications.20

Imaging findings suggestive of failure that the radiologist must evaluate for include widened interfaces between prosthesis and bone (can appear similar to infection), periprosthetic fracture, and serial change in position over time on radiographs.2

4.2. Autograft

Autograft, defined as tissue grafted into a new position in the body of the same individual, provides optimal material for reconstruction of the musculoskeletal system.9 In particular, segments of bone from the patient's iliac crest, tibia, rib or fibula may provide a template for limb reconstruction and salvage. In cases in which limitations of size and shape of the autograft are present, endoprosthesis and allograft are options.9 Additionally, autografts are contraindicated in certain patient populations, particularly in the setting of required postoperative radiation due to its effect on tissue healing.21

Nevertheless, autograft remains a viable surgical option primarily due to its biological origin, which promotes hypertrophy in response to increased load of the limb and promotion of vascularity of tissues.9,22 Since autografts harbor osteogenic cells that permit new bone formation, the use of autograft provides a method of reconstruction using living bone tissue that is capable of remodeling, which improves healing potential and rates of union.23 Free vascularized fibular grafts (FVFG) are particularly effective given their abundant bone source and acceptable donor site morbidity.24 FVFG are employed for intercalary restoration of diaphyseal segmental defect lesions caused by primary or metastatic disease and are a viable alternative to amputation.22

Upon consideration of autograft, a preoperative MRI should be obtained to determine ideal resection margins. Additionally, CT angiography is valuable to determine the availability of transplant vessels and illustrate anatomic variations of extremity vasculature.24 Postoperatively, successful incorporation of the autograft must be monitored via CT imaging. Evidence of graft-host fusion is demonstrated by the appearance of a radiodense line on the endosteal border of the autograft-allograft interface.9 Survival of the vascularized fibula and osteogenesis of the autograft for treatment of a humeral shaft Osteosarcoma is demonstrated in Fig. 2.

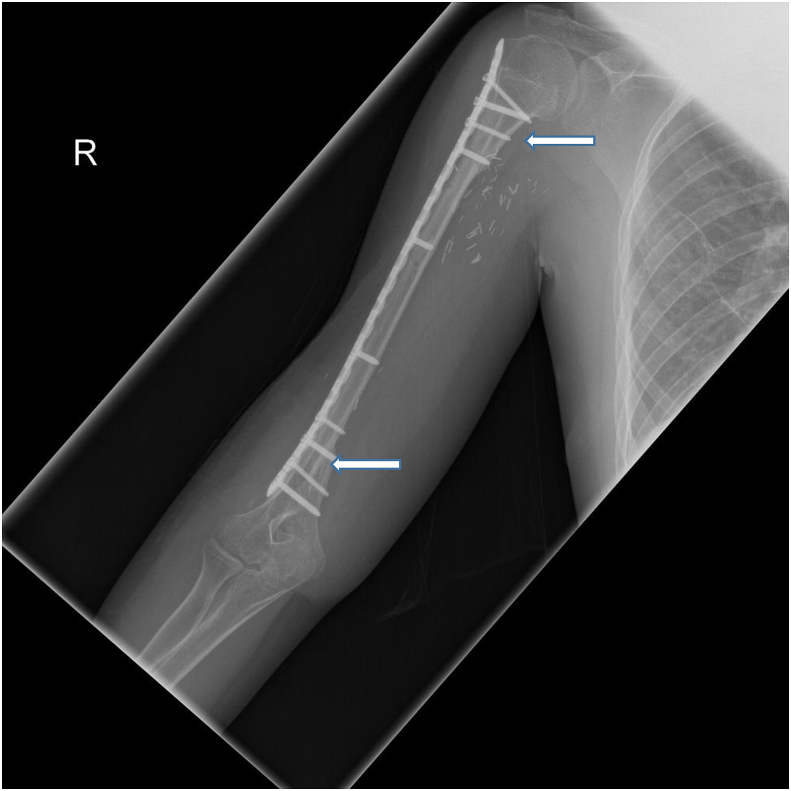

Fig. 2.

Fibular Allograft Intercalary Reconstruction. A 15-year-old male with history of right proximal humerus osteosarcoma. Frontal post-operative radiographic views of the right humerus demonstrate intact intercalary fibular autograft following resection of diaphyseal osteosarcoma. Note complete incorporation of the graft within native bone at the distal and proximal junctional anastomosis (arrows).

4.3. Bulk allograft

Bulk allograft refers to tissue obtained from a different individual, typically from fresh-frozen cadavers, and serves as a reconstructive option for significant osseous and soft tissue defects.25 By restoring bone stock and attaching host ligaments/tendons to the allografts, the surgical technique allows for complex primary reconstructions that are able to support mechanical loads involving the joint.9,26 While allografts pose certain disadvantages, including complications at the host-donor junction from a lack of vascular supply, they remain a viable surgical option primarily due to the allograft's progressive incorporation into host tissue.9,21

Bulk allograft can be further divided into three main types: intercalary, osteoarticular and unicondylar. Each type is optimal for a particular anatomic reconstruction: intercalary for diaphyseal defects, osteoarticular for metaphyseal and epiphyseal defects, and unicondylar for partial articular surfaces. Soft tissue swelling should be of focus upon assessing bulk allograft reconstructions as prolonged swelling after 15–25 weeks postoperatively is the earliest prediction of complications, which include nonunion, graft fractures, cartilage degeneration and progressive arthritis.9 Nevertheless, bulk allograft remains a highly useful reconstructive tool for tumors that are not amenable to prosthetic reconstruction, such as in young patients with primary bone sarcomas as demonstrated in Fig. 3, Fig. 4. The radiologist should be cognizant of the possible complications accompanied with higher rates of fracture, delayed function/weight bearing, and higher rates of infection.21

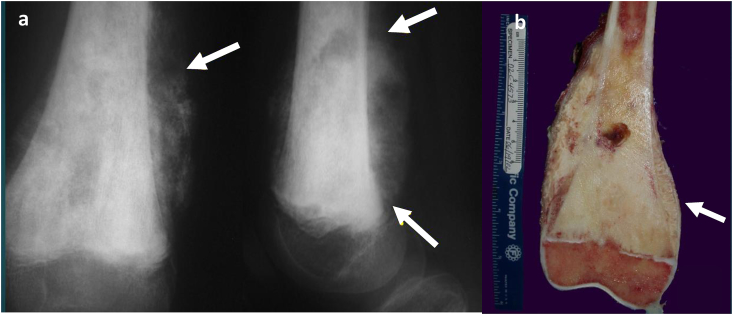

Fig. 3.

(a and b) Distal Femur Bulk Allograft. A patient with osteoblastic osteosarcoma. (a) Frontal and lateral radiographs of the knee demonstrate large mixed sclerotic and lytic lesion with aggressive periosteal reaction (white arrows) with involvement of the distal femoral physis. (b) Gross depiction of the distal femur reveals extensive subperiosteal and physeal involvement (white arrow), necessitating osteoarticular allograft.

Fig. 4.

(a and b) Tibial Diaphyseal Intercalated Allograft Reconstruction. A patient with Ewing sarcoma in the left tibial diaphysis. (a) Coronal and sagittal CT images demonstrate mildly expansile, mixed lytic and sclerotic, marrow-replacing lesion with associated circumferential periosteal and cortical thickening, as well as associated anterior soft tissue component. (b) Coronal and sagittal CT images demonstrate left tibial diaphyseal resection, intercalary graft reconstruction, and myocutaneous flap.

4.4. Allograft prosthetic composite

An additional reconstructive limb salvage alternative is allograft prosthetic composite (APC), which can provide better functional outcomes compared to allograft alone.9,27 The allograft component can provide reconstruction of the extensor mechanism of the knee as in Fig. 5, rotator cuff of the shoulder and abductor muscle in the hip through soft tissue reattachments.9 Furthermore, since APC is resurfaced with prosthetic material, these implants are less likely to undergo the subchondral fragmentation and degeneration that poses problems in bulk allografts.27

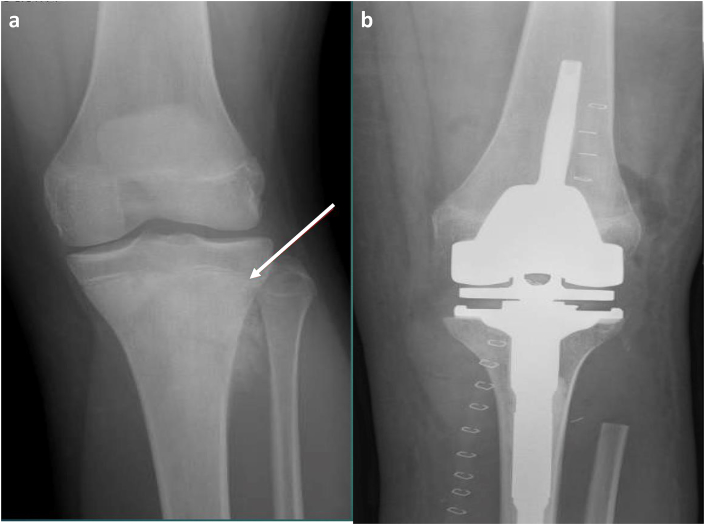

Fig. 5.

(a and b) Tibial Metaphysis Allograft Prosthetic Composite. A patient with osteosarcoma. (a) Pre-operative frontal view demonstrates an aggressive sclerotic lesion in the proximal tibial metaphysis with extension into the physis (white arrow). There is periosteal reaction with fibular extension. (b) Post-operative frontal view shows proximal tibia and fibular head resection with allograft prosthetic composite reconstruction.

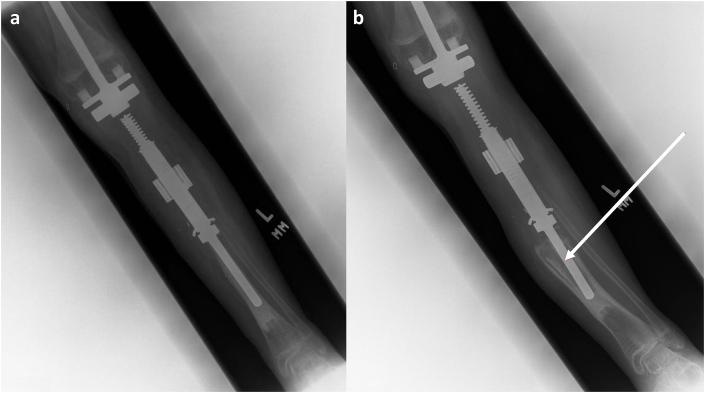

Although APC was introduced in an aim to reduce complications associated with endoprosthesis alone, specifically aseptic loosening, it is not devoid of its own complications. Complications include periprosthetic bone resorption, infection and non-union at the graft-host bone junction as shown in Fig. 6.28,29 Similar to bulk allografts, particular attention to the radiographic presence of a bridging callus directly bonded to both allograft and native bone is paramount in assessing union. The presence of a lucent line at the junctional cortex after 9 months, along with cortices that are not entirely united is concerning for non-union.27

Fig. 6.

(a and b) Non-Union of the Graft-Host Junction. A 28-year-old male with history of Ewing sarcoma of the proximal tibia. (a) Frontal radiographic views of the right tibia following APC reconstruction demonstrate non-union of the graft-host junction with lucency around the hardware (white arrow) reflecting osteolysis and hardware loosening. (b) Frontal radiographic view of the right tibia after revision with proximal tibia endoprosthesis.

5. Complications

5.1. Aseptic loosening

Aseptic loosening is often implicated in limb salvage surgery. It comprises 35% of all complications due to prostheses, most frequently affecting the proximal tibia and distal femoral implants.29 While the incidence of aseptic loosening varies significantly, the rates are higher in younger patients and in patients in which a large portion of bone is resected.29 Several factors contribute to the loosening of the implant: wide excision of adjacent muscle and bone along with patient deconditioning predispose to instability, large lengths of endoprostheses lead to high bending stress at the prosthesis-bone interface and constrained joint designs (fixed-hinged knee) impart substantial stress between the endoprosthesis and bone.7 Although improvements in endoprosthetic designs and cementing techniques have led to decreased rates of aseptic loosening, this complication remains a significant issue in limb salvage surgery, leading to the need for revision surgeries.30

Analysis should be performed based on the well-accepted Charnley and Gruen zones when applicable, in which the prosthetic component is divided into distinct zones on the antero-posterior and lateral radiographs to assess loosening in total hip arthroplasty.30 In cases suspicious of aseptic loosening, the post-operative radiographs should be compared to the most recent prior radiographs. Each zone should be assessed for osteolysis and radiolucency >1 mm. Aseptic loosening can be characterized in the following manner: “possibly loose” if the radiolucent zone at the prosthesis-bone interface is between 50 and 100%, “probably loose” if there is a continuous lucent line around the prosthesis with no evidence of migration and “definitely loose” if there is migration of the cement or implant as shown in Fig. 7.30 In such cases, surgical revision and exchange of the necessary components is warranted.

Fig. 7.

(a and b) Tibial Shaft Aseptic Loosening. A patient with proximal tibia osteosarcoma. (a) Post-operative frontal radiograph demonstrates expandable femorotibial endoprosthesis, allowing limb-lengthening with growth. Follow-up (b) frontal radiograph reveals significant lucency at the bone-cement and metal-cement interfaces with marked posterior and varus angulation of the prosthesis and reactive cortical thickening indicative of aseptic loosening (white arrow).

5.2. Periprosthetic infection

Periprosthetic infection typically occurs within the first year following limb salvage surgery and comprises 22% of all post-operative complications, irrespective of the surgical technique.31 Several risk factors for infection have been documented and include post-operative radiation therapy, operations requiring revision procedures and the use of an expandable prostheses in young patients. The proximal tibia is the most common site for infection, occurring in 21–23% of cases, followed by total femoral replacements in 11–16% and then distal femur in 10–13%.32,33

Patients should be monitored clinically for signs of infection, including local warmth, erythema and pain at the site of surgery, along with elevated inflammatory markers such as ESR, CRP, alpha defensin and IL-6.34 In cases of late infection, which may occur several years after surgery, inflammatory signs may not be as discrete, highlighting the important role of imaging studies in diagnosing periprosthetic infection.32

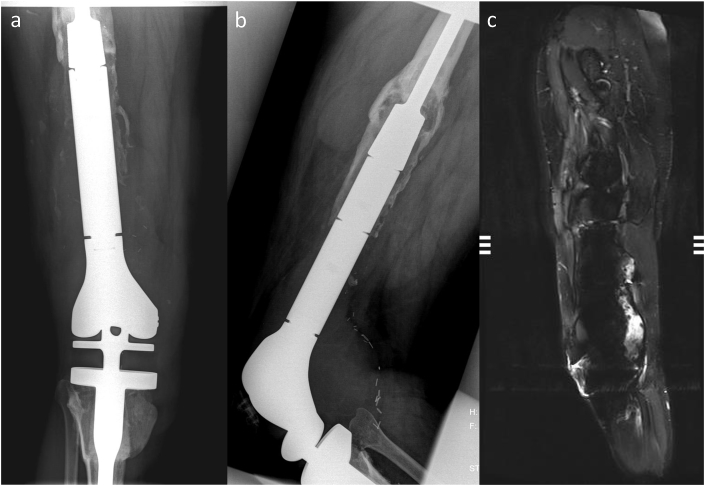

Although low in sensitivity and specificity, radiography is the initial imaging choice by the ACR Appropriateness Criteria to diagnose infection.35 A common radiographic finding in the setting of infection is osteolysis, illustrated as a lucency at the bone-cement or bone-hardware interface greater than 2 mm. While this can be indicative of aseptic loosening, a rapid progression of lucency, cement fractures and periosteal reaction highly support the diagnosis of a periprosthetic infection, as shown in Fig. 8.35 MRI serves a complementary role in addition to plain radiography based on its superior soft-tissue contrast. Via metal artifact reduction, periostitis may be visualized in the setting of infection, correlating to a 99% specificity.35

Fig. 8.

(a, b and c) Femur Periprosthetic Infection. (a) Frontal and (b) lateral radiographs of the right distal femur and proximal tibia with osteolysis surrounding the femoral endoprosthesis and a large, complex effusion at the knee (white arrows). (c) Sagittal STIR MR image demonstrates osteolysis around femoral endoprosthesis with hardware loosening and periprosthetic large enhancing complex collection that extends intra-articularly into the right knee joint pseudocapsule.

CT can also play a role in diagnosis, particularly through contrast-enhancement, which depicts fluid collections, joint effusions and areas of soft-tissue inflammation; however, in most chronic cases these findings are less likely to be seen.36 Although nuclear medicine techniques are not routinely recommended due to the advent of widespread MRI, nuclear medicine can play a role in equivocal cases.35 Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET/CT scans are useful in chronic infections, as FDG accumulates in macrophages around the prosthesis and leads to a relatively high specificity of 88–92% in these cases.36

5.3. Non-Union

Non-union is defined by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as no evidence of healing between graft and native bone within 9 months post-operatively.37,38 Surgical resection of bone tumors often compromise the vascular supply necessary to initiate the reparative process, predisposing to non-union.39 Patients requiring adjuvant therapies, including radiation and chemotherapy, have the highest incidence of non-union as these agents indiscriminately kill both actively dividing tumor cells and the proliferative mesenchymal cells necessary for junctional integration of donor and host bone.39

Non-union should be considered when patients present with persistent pain at the surgical site, particularly when the pain worsens with motion and weight bearing.38 Nonunion is defined radiographically as an absence of bony trabeculae crossing the junction, sclerotic fracture edges, persistent lucent lines and lack of progressive change towards union on serial radiographs.38 In cases in which sclerotic bone and hardware obscure the junction site, CT scans may be a useful adjunct. Non-unions show bone bridging of less than 5% of the cross-sectional area at the junction site while healing non-unions will show bridging greater than 25% of the cross-sectional area.39

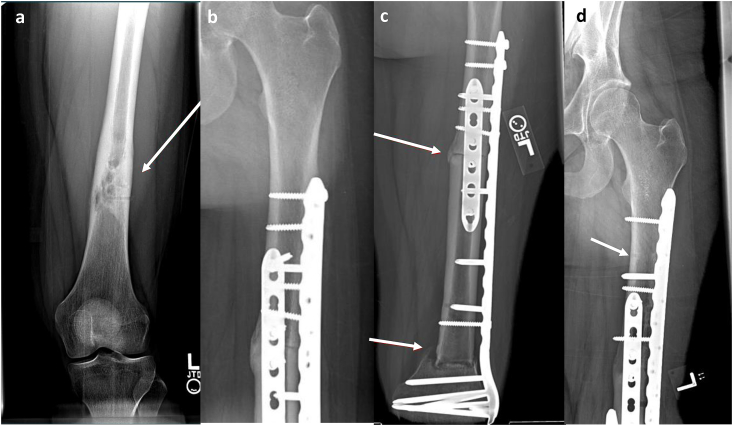

Recently, the use of carbon-fiber-reinforced implants has gained traction in an expanding list of uses in Orthopaedic surgery. Due to the radiolucent characteristic of the implant, it provides artifact-free CT and MR images to allow for radiologists to further evaluate fracture healing at the junction sites.40 While further studies are warranted to investigate the real-world durability of carbon-fiber-reinforced implants, studies have shown carbon-fiber-reinforced implants have comparable biomechanical properties to standard titanium implants.41 Since approximately 70% of patients benefit from revision surgery in cases of non-union, it is imperative for radiologists and clinicians to identify this complication as early as possible, as shown in Fig. 9.39

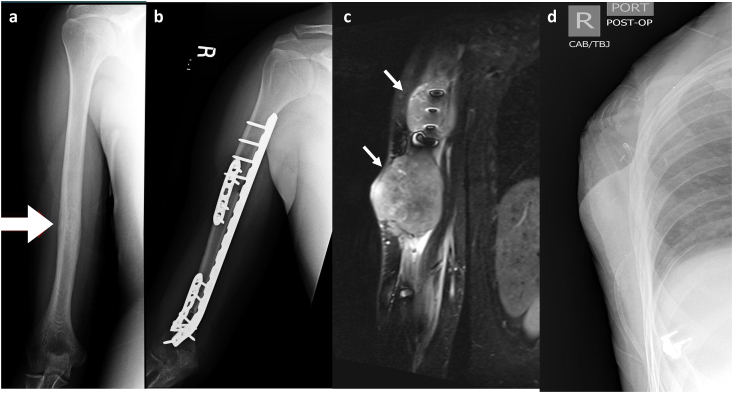

Fig. 9.

(a, b, c and d) Proximal and Distal Femoral Shaft Non-Union. A 20-year-old female with pathology-confirmed osteosarcoma. (a) Frontal radiographs of left femur demonstrate mixed lytic and sclerotic aggressive appearing lesion. The lesion spared the femoral epiphysis, allowing resection into the metaphysis to ensure negative margins and (b) use of allograft reconstruction. Follow-up (c) frontal radiograph demonstrates non-union at the proximal and distal graft-junctions (white arrows). Iliac crest bone graft was applied to accelerate healing of the allograft host junction with subsequent healing on (d) 3-month follow-up frontal film (white arrow).

5.4. Recurrence

One of the most concerning complications involving oncologic musculoskeletal reconstructions is tumor recurrence.7 In primary bone malignancies, recurrence tends to have a poor prognosis, with significantly increased morbidity and decreased overall survival. This is due to greater biologic tumor aggressiveness, and in some cases, systemic spread.42,43 Though specific protocol is variable and dependent on tumor characteristics, surveillance typically involves the use of plain radiographs every 3–6 months for at least 5 years, and then annually thereafter up to 10 years.42,44,45 If there is clinical or radiographic suspicion of recurrence, further cross-sectional imaging is recommended to confirm the diagnosis. MRI is the most appropriate imaging test, following plain radiographs, in order to differentiate recurrent tumor from post-surgical seromas, hematoma, inflammation and scarring.42 Tumor recurrence is illustrated by architectural distortion as shown in Fig. 10, and IV contrast medium may reveal a rounded or ovoid enhancing nodule.10

Fig. 10.

(a, b, c and d) Ewing's Sarcoma Recurrence. A 23-year-old male with Ewing sarcoma. (a) Frontal radiograph demonstrates permeative lytic lesions (white arrows) within humeral shaft with surrounding aggressive periosteal reaction and associated soft tissue mass. (b) Frontal radiographs following tumor resection with intercalary allograft placement and no residual tumor. 2-month follow-up (c) Coronal T2 MRI sequences reveal large T2 hyperintense soft tissue masses (white arrows) at the surgical site, encasing the native bone and allograft, consistent with tumor recurrence. The patient refused treatment at this time and returned to his native country. At 7-month follow-up, limb-sparing surgery was no longer feasible due to axillary extension and metastatic spread. (d) Forequarter amputation of the extremity was subsequently performed.

FDG-PET/CT demonstrates high sensitivity for the detection of distant recurrence, although it is often nonspecific at the operation site as post-surgical inflammatory changes can persist for several years.42,46 However, in a recent meta-analysis, Liu et al. reported excellent accuracy of PET-CT to detect local recurrences after bone sarcoma resections.47

6. Conclusion

Due to advancements made in Orthopaedic surgery over the last several years, multiple reconstructive options are now available for patients with primary bone malignancies. It is important for radiologists to recognize and understand these reconstructive techniques to aid in the early identification of potential complications associated with each option. In cases of aseptic loosening, widened interfaces between prosthesis and bone on serial radiographs is a common finding. Similar imaging findings, though with the addition of periostitis, suggests the presence of infection in the setting of a correlating clinical picture. Non-union reveals a defect between the graft and host bone junction in post-operative radiographs, persisting several months after surgery. Finally, further destruction of bone with the presence of lesions and masses is highly suggestive of tumor recurrence. The ability for radiologists and clinicians to identify complications associated with limb reconstructive surgery can lead to early diagnoses, preventing poor outcomes and maximize patients’ quantity and quality of life.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Jose R. Perez, Email: josep1205@gmail.com.

Jean Jose, Email: jjose@med.miami.edu.

Neil V. Mohile, Email: mohilen@gmail.com.

Allison L. Boden, Email: allison.boden@jhsmiami.org.

Dylan N. Greif, Email: d.greif@med.miami.edu.

Carlos M. Barrera, Email: c.barrera@med.miami.edu.

Sheila Conway, Email: sconway@med.miami.edu.

Ty Subhawong, Email: ty.subhawong@gmail.com.

Ane Ugarte, Email: ane.ugartenuno@gmail.com.

Juan Pretell-Mazzini, Email: j.pretell@med.miami.edu.

References

- 1.Dhammi I.K., Kumar S. Osteosarcoma: a journey from amputation to limb salvage. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48(3):233–234. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.132486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiCaprio M.R., Friedlaender G.E. Malignant bone tumors: limb sparing versus amputation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(1):25–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y., Han L., He Z. Advances in limb salvage treatment of osteosarcoma. J Bone Oncol. 2018;10:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chauhan A., Joshi G.R., Chopra B.K., Ganguly M., Reddy G.R. Limb salvage surgery in bone tumors: a retrospective study of 50 cases in a single center. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013;4(3):248–254. doi: 10.1007/s13193-013-0229-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solooki S., Mostafavizadeh Ardestani S.M., Mahdaviazad H., Kardeh B. Function and quality of life among primary osteosarcoma survivors in Iran: amputation versus limb salvage. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12306-017-0511-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon M.A. Limb salvage for osteosarcoma in the 1980s. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;270:264–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson E.R., Groundland J.S., Pala E. Failure mode classification for tumor endoprostheses: retrospective review of five institutions and a literature review. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 2011;93(5):418–429. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garner H.W., Kransdorf M.J., Peterson J.J. Posttherapy imaging of musculoskeletal neoplasms. Radiol Clin. 2011;49(6):1307–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2011.07.011. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritz J., Fishman E.K., Corl F., Carrino J.A., Weber K.L., Fayad L.M. Imaging of limb salvage surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(3):647–660. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavare A.N., Robinson P., Altoos R. Postoperative imaging of sarcomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211(3):506–518. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.19954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subhawong T.K., Wilky B.A. Value added: functional MR imaging in management of bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Curr Opin Oncol. 2015;27(4):323–331. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holzapfel K., Regler J., Baum T. Local staging of soft-tissue sarcoma: emphasis on assessment of neurovascular encasement-value of MR imaging in 174 confirmed cases. Radiology. 2015;275(2):501–509. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talbot B.S., Weinberg E.P. MR imaging with metal-suppression sequences for evaluation of total joint arthroplasty. Radiographics. 2016;36(1):209–225. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritz J., Fritz B., Thawait G.K. Advanced metal artifact reduction MRI of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty implants: compressed sensing acceleration enables the time-neutral use of SEMAC. Skeletal Radiol. 2016;45(10):1345–1356. doi: 10.1007/s00256-016-2437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar N.M., de Cesar Netto C., Schon L.C., Fritz J. Metal artifact reduction magnetic resonance imaging around arthroplasty implants: the negative effect of long echo trains on the implant-related artifact. Invest Radiol. 2017;52(5):310–316. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bley T.A., Wieben O., Uhl M. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging in musculoskeletal radiology: applications in trauma, tumors, and inflammation. Magn Reson Imag Clin N Am. 2009;17(2):263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Grande F., Subhawong T., Weber K., Aro M., Mugera C., Fayad L.M. Detection of soft-tissue sarcoma recurrence: added value of functional MR imaging techniques at 3.0 T. Radiology. 2014;271(2):499–511. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gkavardina A., Tsagozis P. The use of megaprostheses for reconstruction of large skeletal defects in the extremities: a critical review. Open Orthop J. 2014;8:384–389. doi: 10.2174/1874325001408010384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sevelda F., Schuh R., Hofstaetter J.G., Schinhan M., Windhager R., Funovics P.T. Total femur replacement after tumor resection: limb salvage usually achieved but complications and failures are common. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2079–2087. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4282-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orlic D., Smerdelj M., Kolundzic R., Bergovec M. Lower limb salvage surgery: modular endoprosthesis in bone tumour treatment. Int Orthop. 2006;30(6):458–464. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0193-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capanna R., Campanacci D.A., Belot N. A new reconstructive technique for intercalary defects of long bones: the association of massive allograft with vascularized fibular autograft. Long-term results and comparison with alternative techniques. Orthop Clin N Am. 2007;38(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2006.10.008. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray P.M. Free vascularized bone transfer in limb salvage surgery of the upper extremity. Hand Clin. 2004;20(2):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2004.03.005. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin A.S., Arkader A., Morris C.D. Reconstruction following tumor resections in skeletally immature patients. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25(3):204–213. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panagopoulos G.N., Mavrogenis A.F., Mauffrey C. Intercalary reconstructions after bone tumor resections: a review of treatments. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2017;27(6):737–746. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-1985-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers G.J., Abudu A.T., Carter S.R., Tillman R.M., Grimer R.J. Endoprosthetic replacement of the distal femur for bone tumours: long-term results. J Bone Jt Surg Br Vol. 2007;89(4):521–526. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayerza M.A., Piuzzi N.S., Aponte-Tinao L.A., Farfalli G.L., Muscolo D.L. Structural allograft reconstruction of the foot and ankle after tumor resections. Musculoskelet Surg. 2016;100(2):149–156. doi: 10.1007/s12306-016-0413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert N.F., Yasko A.W., Oates S.D., Lewis V.O., Cannon C.P., Lin P.P. Allograft-prosthetic composite reconstruction of the proximal part of the tibia. An analysis of the early results. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 2009;91(7):1646–1656. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gautam D., Malhotra R. Megaprosthesis versus allograft prosthesis composite for massive skeletal defects. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(1):63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unwin P.S., Cannon S.R., Grimer R.J., Kemp H.B., Sneath R.S., Walker P.S. Aseptic loosening in cemented custom-made prosthetic replacements for bone tumours of the lower limb. J Bone Jt Surg Br Vol. 1996;78(1):5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turcotte R.E., Stavropoulos N.A., Toreson J., Alsultan M. Radiographic assessment of distal femur cemented stems in tumor endoprostheses. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2017;27(6):821–827. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-1965-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeegen E.N., Aponte-Tinao L.A., Hornicek F.J., Gebhardt M.C., Mankin H.J. Survivorship analysis of 141 modular metallic endoprostheses at early followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;420:239–250. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200403000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakarun C.J., Learch T.J., White E.A. Limb-sparing surgery for distal femoral and proximal tibial bone lesions: imaging findings with intraoperative correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(2):W193–W203. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natarajan M.V., Balasubramanian N., Jayasankar V., Sameer M. Endoprosthetic reconstruction using total femoral custom mega prosthesis in malignant bone tumours. Int Orthop. 2009;33(5):1359–1363. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0737-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeys L.M., Grimer R.J., Carter S.R., Tillman R.M. Periprosthetic infection in patients treated for an orthopaedic oncological condition. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 2005;87(4):842–849. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpfendorfer C.S. Radiologic approach to musculoskeletal infections. Infect Dis Clin. 2017;31(2):299–324. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nodzo S.R., Bauer T., Pottinger P.S. Conventional diagnostic challenges in periprosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(Suppl):S18–S25. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.(USFDA) USFaDA . 1988. Guidance Document for Industry and CDRH Staff for the Preparation of Investigational Device Exemptions and Premarket Approval Application for Bone Growth Stimulator Devices. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Somford M.P., van den Bekerom M.P., Kloen P. Operative treatment for femoral shaft nonunions, a systematic review of the literature. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2013;8(2):77–88. doi: 10.1007/s11751-013-0168-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hornicek F.J., Gebhardt M.C., Tomford W.W. Factors affecting nonunion of the allograft-host junction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:87–98. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hak D.J., Mauffrey C., Seligson D., Lindeque B. Use of carbon-fiber-reinforced composite implants in orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2014;37(12):825–830. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20141124-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li C.S., Vannabouathong C., Sprague S., Bhandari M. The use of carbon-fiber-reinforced (CFR) PEEK material in orthopedic implants: a systematic review. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;8:33–45. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S20354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ezuddin N.S., Pretell-Mazzini J., Yechieli R.L., Kerr D.A., Wilky B.A., Subhawong T.K. Local recurrence of soft-tissue sarcoma: issues in imaging surveillance strategy. Skeletal Radiol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00256-018-2965-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson M.E. Update on survival in osteosarcoma. Orthop Clin N Am. 2016;47(1):283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cascade P.N. The American College of radiology. ACR appropriateness Criteria project. Radiology. 2000;214(Suppl):3–46. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan T.J., Aljefri A.M., Clarkson P.W. Imaging of limb salvage surgery and pelvic reconstruction following resection of malignant bone tumours. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84(9):1782–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts C.C., Kransdorf M.J., Beaman F.D. ACR appropriateness Criteria follow-up of malignant or aggressive musculoskeletal tumors. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(4):389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu F., Zhang Q., Zhu D. Performance of positron emission Tomography and positron emission tomography/computed Tomography using fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose for the diagnosis, staging, and recurrence assessment of bone sarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim) 2015;94(36) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]