Abstract

With the accomplishment of human genome sequencing, the number of sequence-known proteins has increased explosively. In contrast, the pace is much slower in determining their biological attributes. As a consequence, the gap between sequence-known proteins and attribute-known proteins has become increasingly large. The unbalanced situation, which has critically limited our ability to timely utilize the newly discovered proteins for basic research and drug development, has called for developing computational methods or high-throughput automated tools for fast and reliably identifying various attributes of uncharacterized proteins based on their sequence information alone. Actually, during the last two decades or so, many methods in this regard have been established in hope to bridge such a gap. In the course of developing these methods, the following things were often needed to consider: (1) benchmark dataset construction, (2) protein sample formulation, (3) operating algorithm (or engine), (4) anticipated accuracy, and (5) web-server establishment. In this review, we are to discuss each of the five procedures, with a special focus on the introduction of pseudo amino acid composition (PseAAC), its different modes and applications as well as its recent development, particularly in how to use the general formulation of PseAAC to reflect the core and essential features that are deeply hidden in complicated protein sequences.

Keywords: PseAAC, Functional domain mode, Gene ontology mode, Sequential evolution mode, Cross-validation

1. Introduction

With the explosive growth of protein sequences generated in the postgenomic age, scientists are anxious to know their attributes because they are closely correlated with the structures and functions of the proteins as well as their roles in biological processes, and hence are very important to both basic research and drug target development. For instance, given an uncharacterized protein sequence, what is its folding rate? Which structural class and quaternary structural attribute does it belong to? Which subcellular location site does it resides? Can it simultaneously exist in or move between two and more subcellular locations? How can we identify it as an enzyme or non-enzyme? If it is an enzyme, to which enzyme functional class does it belong? Is it a membrane protein or non-membrane protein? If the former, to which membrane protein type does it belong? Is it a protease? If it is, to which protease type does it belong? Is it a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)? If it is, to which GPCR type does it belong? Which part of the protein serves as its signal sequence? Where are its cleavage sites by proteases such as HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) protease and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) enzyme? And so forth. Although the answers to these questions can be determined by conducting various biochemical experiments, it is both time-consuming and costly by relying on experimental approaches alone. As a consequence, the gap between the number of newly discovered protein sequences and the knowledge of their attributes is continuing to expand. To bridge such a gap and acquire these kinds of information in a timely manner, scientists are challenged to develop computational methods for predicting various attributes of proteins based on their sequence information alone.

To establish a really useful predictor in this regard, one usually needs to accomplish the following procedures: (1) construct a valid benchmark dataset to train and test the predictor; (2) formulate the protein samples with an effective mathematical expression that can truly reflect their intrinsic correlation with the attribute to be predicted; (3) introduce or develop a powerful algorithm (or engine) to operate the prediction; (4) properly perform cross-validation tests to objectively evaluate the accuracy of the predictor; and (5) establish a user-friendly web-server for the predictor that is accessible to the public.

This review will discuss each of the above five procedures, with a special focus on procedure 2, particularly on how to use various different modes of pseudo amino acid composition to represent protein samples by incorporating their core and essential features.

2. Benchmark dataset

To develop a statistical prediction method for a given attribute, the first important thing is to construct a benchmark dataset according to its possible classification, i.e.

| (1) |

where represents the subset for category 1 of the attribute, for category 2, and so forth; while represents the symbol for “union” in the set theory, and M the number of different categories for the attribute concerned. For example, when the attribute concerned was about the protein structural classification as investigated in Chou (1995a), Chou and Zhang (1994), Chou (1989), Levitt and Chothia (1976), Nakashima et al. (1986) and Zhou (1998), M would be four as illustrated in Fig. 1; when the structural classification was defined according to the SCOP database (Murzin et al., 1995) or investigated in Chou and Cai (2004b), M would be seven as shown in Fig. 2; when the attribute was about the membrane protein type as investigated in Chou and Shen (2007d), M would be eight (Chou and Shen, 2007d) as illustrated in Fig. 3; when the attribute was about the subcellular localization of eukaryotic proteins as investigated in Chou and Shen (2010a), M would be 22 as illustrated in Fig. 4.

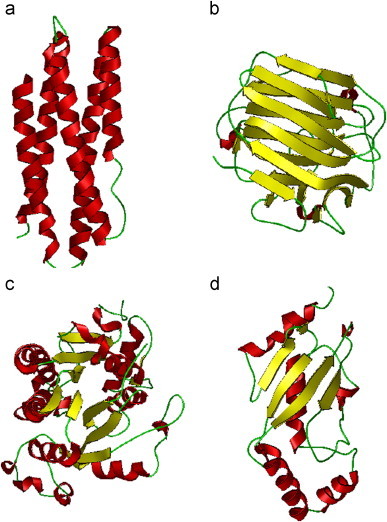

Fig. 1.

Illustration to show the four categories of protein structural class: (a) all-α, (b) all-β, (c) α/β, and (d) α+β, where the α-helix is colored in red, β-strand in yellow, and the other in green. The PDB codes used to draw the representatives of the four structural classes are 1aep, 1gbg, 1enp, and 1aak, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

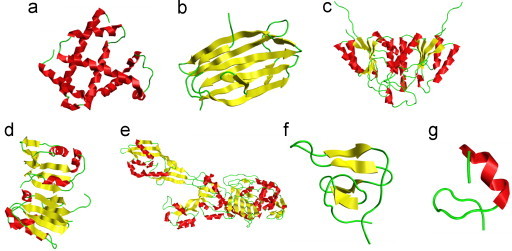

Fig. 2.

Illustration to show the seven categories of protein structural class: (a) all-α, (b) all-β, (c) α/β, (d) α+β, (e) μ (multi-domain), (f) σ (small protein), and (g) ρ (peptide), where the α-helix is colored in red, β-strand in yellow, and the other in green. The PDB codes used to draw the representatives of the seven structural classes are 1a6m, 1uzv, 2f62, 2bf5, 1vqq, 4hir, and 1ter, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

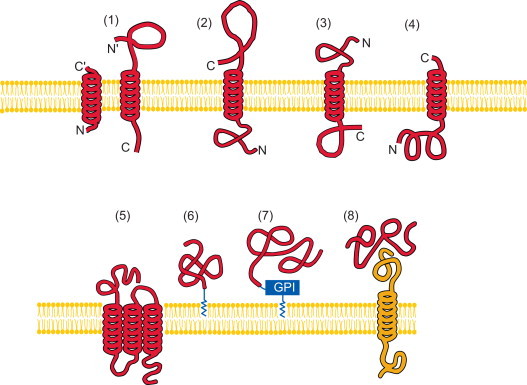

Fig. 3.

Schematic drawings to show the eight categories of membrane protein types: (1) type I transmembrane, (2) type II, (3) type III, (4) type IV, (5) multipass transmembrane, (6) lipid-chain-anchored membrane, (7) GPI-anchored membrane, and (8) peripheral membrane. As shown in the figure, types I, II, III, and IV are all of single-pass transmembrane proteins; see Spiess (1995) for a detailed description about their difference.

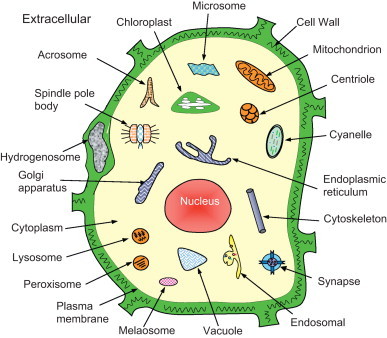

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration to show the 22 subcellular locations of eukaryotic proteins: (1) acrosome, (2) cell wall, (3) centriole, (4) chloroplast, (5) cyanelle, (6) cytoplasm, (7) cytoskeleton, (8) endoplasmic reticulum, (9) endosome, (10) extracellular, (11) Golgi apparatus, (12) hydrogenosome, (13) lysosome, (14) melanosome, (15) microsome (16) mitochondria, (17) nucleus, (18) peroxisome, (19) plasma membrane, (20) plastid, (21) spindle pole body, and (22) vacuole.

To avoid homology bias and redundancy, it is important to introduce a cutoff threshold when constructing a benchmark dataset. Different cutoff threshold values were used, such as 90% (Reinhardt and Hubbard, 1998), 80% (Small et al., 2004), 40% (Shen and Chou, 2007a), and 25% (Chou and Shen, 2010a, Chou and Shen, 2010c). When a benchmark dataset was constructed with the cutoff threshold of 25%, none of the proteins included would have ≥25% pairwise sequence identity to any other in the same subset (category). Accordingly, the smaller the cutoff threshold is, the more stringent the benchmark dataset will be in excluding the homology bias.

The benchmark datasets constructed in the earlier stage (see, e.g., Cedano et al., 1997, Chou, 1989, Nakashima et al., 1986) usually consisted of a learning (or training) dataset and an independent testing dataset, as can be formulated as

| (2) |

where is the learning dataset, the training dataset, the empty set, and the symbol for “intersection” in the set theory. The learning dataset is used for training the predictor's “engine”, while the testing dataset used for evaluating the predictor's accuracy via a cross-validation. As we can see from Eq. (2), none of the proteins in the testing dataset should occur in the learning dataset . Therefore, is also called an independent dataset for performing cross-validation. However, as will be shown later, there is no need to artificially separate the benchmark dataset into a learning dataset and a testing dataset when the cross-validation is performed by the jackknife test, in which case one benchmark dataset can serve both the training and testing purposes.

3. Protein sample representation

Two kinds of models were usually used to represent protein samples. One is the sequential model, and the other the discrete model. The most straightforward sequential model for a protein sample is its entire amino acid sequence, as expressed by

| (3) |

where R1 represents the 1st residue of the protein P, R2 the 2nd residue,…, RL the L-th residue, and they each belong to one of the 20 native amino acid types. To get the desired results, the sequence-similarity-search-based tools, such as BLAST (Altschul, 1997, Wootton and Federhen, 1993), are usually utilized to conduct the prediction. However, this kind of approach failed to work when the query protein did not have significant sequence similarity to any attribute-known proteins. Thus, various non-sequential models, or discrete models, were proposed, as illustrated below.

The simplest discrete model used to represent a protein sample is its amino acid (AA) composition or AAC (Nakashima et al., 1986). According to the AAC-discrete model, the protein P of Eq. (3) can be expressed by (Chou, 1995a)

| (4) |

where f i (i=1, 2 ,…,20) are the normalized occurrence frequencies of the 20 native amino acids in P, and T the transposing operator. Many methods for predicting various protein attributes were based on the AAC-discrete model (see, e.g., Cedano et al., 1997, Chou, 1999, Chou, 2000, Chou, 2005b, Chou and Zhang, 1992, Chou and Zhang, 1995, Chou and Maggiora, 1998, Chou and Elrod, 1999, Chou and Elrod, 2002, Chou et al., 1998, Chou, 1989, Du et al., 2006, Feng et al., 2005, Jahandideh et al., 2007a, Klein, 1986, Klein and Delisi, 1986, Liu and Chou, 1998, Metfessel et al., 1993, Nakashima and Nishikawa, 1994, Niu et al., 2006, Zhou, 1998, Zhou and Assa-Munt, 2001, Zhou and Doctor, 2003). However, as one can see from Eq. (4), all the sequence-order effects would be missing using the AAC-discrete model, and hence the prediction quality thus obtained might be limited. This is the main shortcoming of the AAC discrete model. To avoid completely losing the sequence-order information, a completely different discrete model, or the so-called “pseudo amino acid composition” (PseAAC) model (Chou, 2001), was proposed to represent the sample of a protein, as formulated by

| (5) |

where the first 20 elements are associated with the 20 elements in Eq. (4) or the 20 amino acid components of the protein, while the additional Λ factors are used to incorporate some sequence-order information via various modes. Typically, these additional factors are a series of rank-different correlation factors along a protein chain, but they can also be any combinations of other factors so long as they can reflect some sorts of sequence-order effects in one way or the other. For the convenience of users, a web-server called “PseAAC” (Shen and Chou, 2008) was established at http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/PseAAC/, by which some commonly used PseAAC forms can be automatically generated.

The concept of PseAAC has been widely used to study various problems in proteins and protein-related systems, such as predicting enzymes and their family/sub-family classification (Cai and Chou, 2005, Cai et al., 2005, Qiu et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2010b, Zhou et al., 2007), protein subcellular location prediction (Cai and Chou, 2003, Chou and Cai, 2003c, Chou and Cai, 2004e, Gao et al., 2005, Li and Li, 2008b, Pan et al., 2003, Shi et al., 2007, Shi et al., 2008, Xiao et al., 2006b, Zhang et al., 2008c), apoptosis protein subcellular location prediction (Chen and Li, 2007, Jiang et al., 2008b, Kandaswamy et al., 2010, Lin et al., 2009a, Liu et al., 2010b), mycobacterial protein subcellular location prediction (Lin et al., 2008), predicting protein subnuclear localization (Jiang et al., 2008a, Li and Li, 2008a, Shen and Chou, 2005b), predicting protein subchloroplast locations (Du et al., 2009), predicting protein submitochondria locations (Du and Li, 2006, Nanni and Lumini, 2008, Zeng et al., 2009), predicting membrane proteins and their types (Cai and Chou, 2006, Chou and Shen, 2007d, Liu et al., 2005, Shen and Chou, 2005a, Shen et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2004, Wang et al., 2006), discrimination of outer membrane proteins (Gao et al., 2010, Lin, 2008), identifying transmembrane regions in proteins (Diao et al., 2008), identifying proteases and their types (Chou and Shen, 2008a, Zhou and Cai, 2006), predicting protein solubility (Xiaohui et al., 2010), identifying GPCRs and their classes (Gu et al., 2010a, Gu et al., 2010b, Lin et al., 2009b, Qiu et al., 2009, Xiao et al., 2009b, Xiao et al., 2010b), prediction of nuclear receptors (Gao et al., 2009), prediction of cyclin proteins (Mohabatkar, 2010), identifying bacterial secreted proteins (Yu et al., 2010), identifying risk type of human papillomaviruses (Esmaeili et al., 2010), prediction of cell wall lytic enzymes (Ding et al., 2009), prediction of lipases types (Zhang et al., 2008a), predicting conotoxin superfamily and family (Lin and Li, 2007a, Mondal et al., 2006), predicting the cofactors of oxidoreductases (Zhang and Fang, 2008), predicting DNA-binding proteins (Fang et al., 2008), predict protein structural classes (Chen et al., 2006a, Chen et al., 2006b, Ding et al., 2007, Li et al., 2009, Lin and Li, 2007b, Wu et al., 2010, Xiao et al., 2008a, Xiao et al., 2008b, Xiao et al., 2006a, Zhang and Ding, 2007, Zhang et al., 2008d), supersecondary structure prediction (Zou et al., 2011), protein secondary structure content prediction (Chen et al., 2009), predicting protein quaternary structural attributes (Chou and Cai, 2003a, Shen and Chou, 2009b, Xiao et al., 2009a, Xiao et al., 2010a, Zhang et al., 2008b, Zhang et al., 2006), fold pattern prediction (Shen and Chou, 2006, Shen and Chou, 2009a), and others (e.g., Georgiou et al., 2009).

Meanwhile, various modes of PseAAC by extracting different features from protein sequences were proposed, including stochastic signal processing mode (Pan et al., 2003), Fourier spectrum analysis mode (Liu et al., 2005), special functions mode (Gao et al., 2005), complexity measure factor mode (Xiao et al., 2005, Xiao et al., 2006a), cellular automaton mode (Xiao et al., 2006b, Xiao et al., 2008b, Xiao et al., 2009b), geometric moments mode (Xiao et al., 2008b), gray dynamic mode (Xiao et al., 2008a), approximate entropy mode (Jiang et al., 2008a), continuous wavelet transform mode (Li et al., 2009), discrete wavelet transform mode (Qiu et al., 2009, Qiu et al., 2010), sequence-segmented mode (Zhang et al., 2008b), evolutionary information and von Neumann entropy mode (Zhang et al., 2008c), and so forth.

However, according to its original concept, the essence of PseAAC is to keep using a discrete model to represent a protein yet without completely losing its sequence-order information. Therefore, in a broad sense, the PseAAC of a protein is actually a set of discrete numbers that is derived from its amino acid sequence and that is different from the classical AAC and able to harbor some sort of sequence order or pattern information. Therefore, the PseAAC for a protein P should be generally formulated as

| (6) |

where the subscript Ω is an integer, and its value and the components ψ 1, ψ 2,… will depend on how to extract the desired information from the amino acid sequence of P (cf. Eq. (3)). The form of Eq. (6) can cover all the aforementioned modes of PseAAC. For example, when

| (7) |

we immediately obtain the formulation of PseAAC originally introduced in Chou (2001), where the meanings for w, θ j, and λ were clearly elaborated and hence there is no need to repeat here. When

| (8) |

we obtain the formulation for the amphiphilic PseAAC (Chou, 2005a), where the meanings of w, τ j, and λ were also clearly given.

It is instructive to point out that, with the general formulation of Eq. (6), the PseAAC can be used to reflect much more essential core features deeply hidden in complicated protein sequences through the following modes.

3.1. Functional domain mode

The functional domain (FunD) is the core of a protein. Therefore, in determining the 3-D (dimensional) structure of a protein by experiments (see, e.g., Call et al., 2010, Pielak and Chou, 2010, Schnell and Chou, 2008, Wang et al., 2009) or by computational modeling (see, e.g., Chou, 2004a, Chou, 2004b), the first priority was always focused on its FunD.

Using the FunD information to formulate protein samples was originally proposed in Cai et al. (2003) and Chou and Cai (2002) based on the 2005 FunDs in the SBASE-A database (Murvai et al., 2001). Since then, a series of new protein FunD databases were established, such as COG (Tatusov et al., 2003), KOG (Tatusov et al., 2003), SMART (Letunic et al., 2006), Pfam (Finn et al., 2006), and CDD (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2007). Of these databases, CDD contains the domains imported from COG, Pfam, and SMART, and hence is relatively much more complete (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2007) and was adopted in most of the recent publications (see, e.g., Chou and Shen, 2010a, Chou and Shen, 2010c, Shen and Chou, 2009d). The version 2.11 of CDD contains 17,402 characteristic domains. Thus, when using the general formulation of PseAAC (Eq. (6)) to incorporate the FunD information, we have Ω=17,402, i.e.

| (9) |

where T has the same meaning as in Eq. (4), and

| (10) |

For the detailed procedure of how to find the hit for P in CDD, refer to Chou and Shen (2010a).

Similar approaches of representing protein samples with the FunD mode were also used for predicting protein subcellular localization (Chou and Cai, 2002, Chou and Cai, 2004d), membrane protein types (Cai and Chou, 2006, Cai et al., 2003), enzyme functional classes (Shen and Chou, 2007a), protease types (Chou and Shen, 2008a, Shen and Chou, 2009c), GPCRs types (Xiao et al., 2010b), protein structural class (Chou and Cai, 2004b), protein fold pattern (Shen and Chou, 2009a), and protein quaternary structural attributes (Shen and Chou, 2009b, Xiao et al., 2009a, Xiao et al., 2010a).

3.2. Gene ontology mode

Gene ontology (GO) database (Ashburner et al., 2000) was established according to the molecular function, biological process, and cellular component. Accordingly, protein samples defined in a GO database space would be clustered in a way better reflecting some of their important attributes, such as subcellular localization and biological function (Chou and Shen, 2007c, Chou and Shen, 2008b).

The GO database (version 70.0 released 10 March 2008) contains 60,020 GO numbers. Thus, when using the general formulation of PseAAC to incorporate the GO information, we have Ω=60,020, i.e.

| (11) |

where

| (12) |

For the detailed procedure of how to find the hit for P in the GO database, refer to Chou and Shen (2010a).

The information extracted from the GO database (Ashburner et al., 2000, Camon et al., 2004, Harris et al., 2004) was used to formulate PseAAC for predicting protein subcellular localization (Cai and Chou, 2003, Chou and Cai, 2003b, Chou and Cai, 2004d, Chou and Shen, 2006a, Chou and Shen, 2006b, Chou and Shen, 2006c, Chou and Shen, 2007a, Chou and Shen, 2007b, Chou and Shen, 2007c, Chou and Shen, 2008b, Lee et al., 2005, Shen and Chou, 2007b, Shen and Chou, 2007c, Shen and Chou, 2007d, Shen et al., 2007), enzyme functional class (Chou and Cai, 2004a, Chou and Cai, 2004c), membrane protein types (Chou and Cai, 2005), protease types (Zhou and Cai, 2006), and protein–protein interactions (Chou and Cai, 2006).

3.3. Sequential evolution mode

Biology is a natural science with historic dimension. All biological species have developed continuously starting out from a very limited number of ancestral species. It is true for protein sequence as well (Chou, 2004b). Their evolution involves changes of single residues, insertions, and deletions of several residues (Chou, 1995b), gene doubling, and gene fusion. With these changes accumulated for a long period of time, many similarities between initial and resultant amino acid sequences are gradually eliminated, but the corresponding proteins may still share many common attributes, such as having basically the same biological function and residing in the same subcellular location.

The general formulation of PseAAC can be used to incorporate this kind of information via its sequential evolution mode, i.e.

| (13) |

where

| (14) |

where λ is an uncertain number that will be further discussed later, L is the length of P (counted in the total number of its constituent amino acids), and E i→j represents the score of the amino acid residue in the i-th position of the protein sequence being changed to amino acid type j during the evolutionary process (Schaffer et al., 2001), which can be derived by using PSI-BLAST (Schaffer et al., 2001) to search the Swiss-Prot database as described in Chou and Shen (2010c). Here, the numerical codes 1, 2,…,20 are used to denote the 20 native amino acid types according to the alphabetical order of their single character codes.

The above equations were used to identify membrane proteins and their types (Chou and Shen, 2007d), enzymes and their functional classes (Shen and Chou, 2007a), proteases and their types (Chou and Shen, 2008a), protein quaternary structural attributes (Shen and Chou, 2009b), as well as protein subcellular localization (Chou and Shen, 2010a, Chou and Shen, 2010b).

Besides the aforementioned PseAAC modes, there may be some other feature extraction methods to represent protein samples, but they can always be formulated with the form of Eq. (6), the general formulation of PseAAC.

It is instructive to point out that, regardless of which kind of PseAAC mode is adopted for protein samples, the query proteins and the proteins used to train the prediction engine must be defined in the same infrastructural frame with exactly the same dimension. For instance, if a query protein is defined in the 17402-D FunD space (see Eq. (9)), then the prediction should be carried out based on those proteins in the training set that can be defined in the exactly same 17402-D FunD space as well. If a query protein is defined in the 60020-D GO space (see Eq. (11)), then the prediction should be carried out based on those proteins in the training set that can be defined in the exactly same 60020-D GO space as well. If the query protein in both the 17402-D FunD space and 60020-D GO space is a naught vector and hence must be defined instead in the sequential evolution space (see Eq. (13)), then all the proteins used to train the prediction engine must also be formulated in the same sequential evolution space. It is particularly important to follow such a self-consistency principle when hybridizing different PseAAC modes or building an ensemble classifier by fusing many individual classifiers (Chou and Shen, 2006d).

4. Prediction algorithm (operating engine)

The problem of predicting protein attributes can be generally described as follows. Suppose a system containing N proteins (P 1,P 2,…,P N), which have been classified into M subsets (categories) as formulated by Eq. (1), where each subset S m (m=1,2,…,M) is composed of proteins with the same attribute category and its size (the number of proteins therein) is N m. Obviously, we have N=N 1+N 2+⋯+N M. According to Eq. (6), we can suppose without losing generality that the k-th protein in the subset S m (see Eq. (1)) is expressed by

| (15) |

where is the j-th component of the k-th protein in . Now, for a query protein P as defined by Eq. (6), how can we identify which subset it belongs to?

Many different prediction algorithms have been introduced to address this problem, such as discriminant algorithm (Chou and Maggiora, 1998, Chou and Elrod, 1999), neural network algorithm (Cai et al., 2000, Cai et al., 2001), support vector machine (SVM) (Cai et al., 2003, Cai et al., 2004, Chou and Cai, 2002), and K-nearest Neighbor algorithm (Cai and Chou, 2003, Chou and Shen, 2006b). In this paper we shall focus on the K-nearest neighbor algorithm (Denoeux, 1995) and show how to generate a powerful ensemble classifier by fusing many individual basic classifiers characterized with different control parameters.

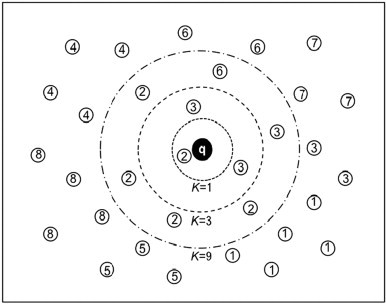

The K-nearest neighbor (KNN) classifier is quite popular in pattern recognition community owing to its good performance and simple-to-use feature. According to the KNN rule (Denoeux, 1995, Keller et al., 1985), named also as the “voting KNN rule”, the query protein should be assigned to the subset represented by a majority of its K nearest neighbors, as illustrated in Fig. 5

Fig. 5.

Illustration to show how the KNN classifier depends on the selection of parameter K in identifying the attribute category of a query protein, where the query protein P is represented by the character q with a filled circle, proteins belonging to subset (category 1) are represented by the open circle with number 1, proteins of by the open circle with number 2, and so forth. When K=1, the query protein is predicted belonging to category 2 as its nearest protein does; when K=3, the query protein is predicted belonging to category 3 because two of its three nearest proteins belong to that category; when K=9, the query protein is predicted belonging to category 2 again because the majority of its nine nearest proteins belong to category 2.

There are many different definitions to measure the “nearness” for the KNN classifier, such as Euclidean distance, Hamming distance (Mardia et al., 1979), and Mahalanobis distance (Chou, 1995a, Mahalanobis, 1936, Pillai, 1985). Usually, the following equation was adopted to measure the nearness between proteins P and (cf. Eqs. (6), (15)):

| (16) |

where is the dot product of the two vectors, and ‖P‖ and their modulus, respectively. According to Eq. (16), when we have , indicating the “distance” between these two proteins is zero and hence they have perfect or 100% similarity. In using the KNN rule, the predicted result will depend on the selection of the parameter K, the number of the nearest neighbors to the query protein P, as described below.

4.1. Nearest neighbor classifier

The nearest neighbor classifier (Cover and Hart, 1967), also called NN classifier, is a special case of KNN classifier with K=1 (Fig. 5). With the NN classifier, the protein P will be predicted belonging to the same attribute category of the protein in the learning dataset that has the shortest “distance” to P, i.e., the query protein will be classified in the μ-th attribute category if

| (17) |

where means taking the minimum value of for the proteins in the subset (cf. Eqs. (1) and (16)), and the operator arg minm means taking the argument of m that minimizes the quantity right after the operator. In other words, μ in Eq. (17) is equal to the argument of m that minimizes . If there are two and more arguments leading to the same minimum value, the query protein will be randomly assigned to one of the subsets associated with these arguments although this kind of tie case rarely happens. Owing to its simplicity and apparent efficiency, the NN classifier is still a favorite method used by many investigators (see, e.g., Chen et al., 2010, He et al., 2010, Huang et al., 2010).

4.2. KNN classifier

With the KNN classifier when K>1, the attribute of the query protein P will be determined by the majority of its K nearest neighbors via a vote (Fig. 5), as can be formulated as follows. Suppose are the K proteins in that have the closest distances to P, the query protein will be predicted belonging to the μ-th subset (attribute category) if

| (18) |

where μ is the argument of m that maximize and

| (19) |

where ∈ is a symbol in the set theory meaning “member of”. If there is a tie for the voting results, the query protein will be randomly assigned to one of the locations associated with the tie case. Generally speaking, the greater the K (the number of the nearest neighbors counted), the less likely the tie case occurs.

As mentioned above, the sequential evolution PseAAC mode of Eq. (13) contains a parameter λ, which is associated with what tier of sequence correlation is taken into account for the PseAAC. As we can see from Eq. (14), the only constraint to λ is that it must be smaller than L, the number of the amino acids in the protein concerned. Suppose the length of the shortest protein investigated is 50, then λ can be any of the following 50 numbers: 0, 1, 2,…,49. Although in principle we can include all these possibilities for λ by enlarging the dimension of the PseAAC to contain 20×50=1000 components, it may cause various unfavorable problems for statistical prediction, such as “high dimension disaster” and “overfitting redundancy” (Wang et al., 2008a). Actually, it may reduce the cluster-tolerant capacity (Chou, 1999) and lower down the success rate of cross-validation if the PseAAC contains too many trivial components. Accordingly, for a given training dataset, there is an optimal number for λ. However, it would be time-consuming and tedious to find the optimal λ by changing its value and doing tests one-by-one.

Likewise, the KNN classifier (cf. Eq. (18)) also contains a parameter K, the number of the nearest neighbors to a query protein (Fig. 5). It will affect the predicted result by choosing a different value for K. In other words, for a given training dataset, there is an optimal value for K as well.

The parameters such as λ and K are called uncertain parameters. The number of the uncertain parameters depends on which model is used to represent the protein samples and what classifier is used for the prediction engine. It can be seen from Eqs. (9), (11), (13), and (18) that one uncertain parameter, K, needs to be determined if using KNN classifier based on the FunD (or GO) mode of PseAAC, and that two uncertain parameters, K and λ, need to be determined if using KNN classifier based on the sequential evolution mode. It would be much more tedious and time-consuming to determine the optimal values for two uncertain parameters. To deal with this kind of uncertain parameters, let us introduce the fusion approach.

4.3. One-dimensional fusion

For most cases in using the KNN classifier to predict protein attributes, when K>20, the success rate by the KNN classifier would decrease remarkably. Therefore, the basic individual classifiers to be considered can be generally expressed as

| (20) |

where represents the KNN classifier that is a function of K, the symbol is the identification operator meaning using to identify the attribute of the query protein P among the M subsets of in Eq. (1). Suppose the accumulated score thus obtained (with K=1,2,…,20) for the protein P belonging to the m-th subset is given by

| (21) |

where

| (22) |

Thus the query protein P is predicted belonging to the subset with which its score of Eq. (21) is the highest, i.e., the query protein P is identified as belonging to the μ-th subset if

| (23) |

where μ is the argument of m that maximizes the score function of Eq. (21). If there are two and more arguments leading to the same maximum value, the query protein will be randomly assigned to one of the subset associated with these arguments although this kind of tie case rarely happens.

4.4. Two-dimensional fusion

When the KNN classifier is operated on the query protein formulated with the sequential evolution mode (cf. Eq. (13)), we are facing a problem with two uncertain parameters, K and λ. In general, the shortest protein sequence investigated is 50 amino acids (Chou and Shen, 2008a, Chou and Shen, 2010c), hence we can set the maximum value allowed for λ is 49. Thus, the basic individual classifiers to be considered would become as follows:

| (24) |

and the corresponding accumulated score for the query protein belonging to the m-th subset is given by

| (25) |

where

| (26) |

and the query protein is predicted belonging to the subset with which its score of Eq. (25) is the highest, i.e., the query protein P is identified as belonging to the μ-th subset if

| (27) |

where μ is the argument of m that maximizes the score function of Eq. (25). If there are two and more arguments leading to the same maximum value, the query protein will be randomly assigned to one of the subcellular locations associated with these arguments although this kind of tie case rarely happens.

If a basic individual classifier involves with three or more uncertain parameters, by following the similar procedures as described above, we can perform three or higher dimensional fusion.

5. Cross-validation test

After a prediction method has been developed, a subsequent and natural question to ask is: What is its accuracy?

In statistical prediction, it would be meaningless to simply say a success rate of a predictor without specifying what cross-validation method and benchmark dataset were used to test its accuracy. In literatures, the following three cross-validation methods are generally used for examining the effectiveness of a statistical prediction method: (1) the independent dataset test, (2) the subsampling (Γ-fold such as 5- or 10-fold cross-validation) test, and (3) the jackknife test (Chou and Zhang, 1995).

For the independent dataset test, although all the proteins used to test the predictor are outside the training dataset used to train it so as to exclude the “memory” effect or bias, the way of how to select the independent proteins to test the predictor could be quite arbitrary unless the number of independent proteins is sufficiently large. This kind of arbitrariness might result in completely different conclusions. For instance, a predictor achieving a higher success rate than the other predictor for a given independent testing dataset might fail to keep so when tested by another independent testing dataset (Chou and Zhang, 1995). Accordingly, the independent dataset test is not a fairly objective test method although it was often used to demonstrate the practical application of a predictor (see, e.g., Cedano et al., 1997, Chou and Elrod, 1999, Chou and Shen, 2006c, Chou and Shen, 2007a).

For the subsampling test, the concrete procedure usually used in literatures is the 5-fold, 7-fold, or 10-fold cross-validation. The problem with the Γ-fold cross-validation test as such is that the number of possible selections in dividing a benchmark dataset is an astronomical figure even for a very simple dataset. This is because for a benchmark dataset as formulated in Eq. (1), the number of possible combinations of taking one Γ-th or 1/Γ proteins from each of the subsets in Eq. (1) will be

| (28) |

where

| (29) |

where N m is the number of proteins in the m-th subset , and the symbol Int is the integer-truncating operator meaning to take the integer part for the number in the brackets right after it.

For example, without losing generality let us consider the case of 5-fold cross-validation (i.e., Γ=5) for a very simple benchmark dataset that contains 250 proteins, of which N 1=65 belongs to subset , N 2=60 to subset , N 3=55 to subset , and N 4=70 to subset . Substituting these figures into Eqs. (28), (29), we have that the number of possible combinations of taking one-fifth proteins from each of the four subsets will be

| (30) |

indicating that for such a simple and small benchmark dataset, the number of possible combinations of taking one-fifth proteins from each of the four subsets for 5-fold cross-validation will be an astronomical number.

Now let us consider a moderate-size dataset that consists of 640 proteins classified into M=8 subsets with each containing 80 proteins, i.e., N 1=N 2=⋯=N 8=80. According to Eqs. (28), (29), the number of possible combinations of taking one-fifth proteins from each of the 8 subsets for 5-fold-cross-validation will be

| (31) |

If the above benchmark dataset is slightly larger and complicated, i.e., the number of proteins is increased from 640 to 800, and the number of subsets from 8 to 10 with each still containing 80 proteins, then the number of possible combinations of taking one-fifth proteins from each of the 10 subsets for 5-fold-cross-validation will be

| (32) |

Actually, many typical benchmark datasets contain more than 1000 proteins (see, e.g., Chou and Shen, 2008a, Chou and Shen, 2010a, Chou and Shen, 2010c). Therefore, in any actual subsampling cross-validation tests, only an extremely small fraction of the possible selections are taken into account. Since different selections will always lead to different results even for a same benchmark dataset and a same predictor, the subsampling test (such as 5-fold cross-validation) cannot avoid the arbitrariness either. A test method unable to yield a unique outcome cannot be deemed as an ideal one.

In the jackknife test, all the proteins in the benchmark dataset will be singled out one-by-one and tested by the predictor trained by the remaining protein samples. During the process of jackknifing, both the training dataset and testing dataset are actually open, and each protein sample will be in turn moved between the two. The jackknife test can exclude the “memory” effect. Also, the arbitrariness problem as mentioned above for the independent dataset test and subsampling test can be avoided because the outcome obtained by the jackknife cross-validation is always unique for a given benchmark dataset. As for the possible overestimation in success rate by jackknife test because of only one sample being singled out at a time for testing, the answer is that as long as the jackknife test is performed on a stringent benchmark dataset in which none of proteins has ≥25% pairwise sequence identity to any other in a same subset such as those mentioned in the Section 2, it is highly unlikely to yield an overestimated rate compared with the actual success rate in practical applications, as demonstrated in Chou and Shen ( 2010c) and Shen and Chou (2010). Besides, when the jackknife test was used to compare two predictors, even if there was some overestimate due to using a less stringent benchmark dataset for one predictor, the same overestimate would exist for the other as long as they were both tested by the same dataset.

Accordingly, the jackknife test has been increasingly and widely used by investigators to examine the quality of various predictors (see, e.g., Anand and Suganthan, 2009, Cai et al., 2010, Chen et al., 2008a, Chen et al., 2008b, Chen and Han, 2009, Du and Li, 2008, Du et al., 2009, Fang et al., 2008, Feng and Luo, 2008, Gu and Chen, 2009, Gu et al., 2010a, Jahandideh et al., 2007a, Jahandideh et al., 2007b, Jahandideh et al., 2009, Ji et al., 2010, Kannan et al., 2008, Li et al., 2009, Lin, 2008, Lin et al., 2009a, Liu et al., 2010a, Munteanu et al., 2008, Nanni and Lumini, 2008, Nanni and Lumini, 2009, Rezaei et al., 2008, Shao et al., 2009, Shi et al., 2008, Shi and Hu, 2010, Vilar et al., 2009, Wang and Yang, 2010, Wang et al., 2010a, Wang et al., 2008b, Yang and Jiang, 2010, Yang et al., 2009, Yang et al., 2010, Zhao et al., 2008, Zhou et al., 2008).

However, even if using the jackknife approach for cross-validation, the same predictor may still generate obviously different success rates when tested by different benchmark datasets. This is because the more the stringent of a benchmark dataset in excluding homologous and high similarity sequences, the more the difficult for a predictor to achieve a high overall success rate (Chou and Shen, 2010a). Also, the more the number of subsets (attribute categories) a benchmark dataset covers, the more the difficult to achieve a high overall success rate. This can be easily conceivable via the following consideration. Suppose a benchmark dataset consists of two subsets (attribute categories) with each containing the same number of proteins. The overall success rate in identifying their attribute categories by random assignment would be 1/2=50%. However, for a benchmark dataset consisting of 20 subsets, the corresponding overall success rate by the random assignment would be 1/20=5%, which is only one-tenth of the former.

6. Web-server

Even if a powerful predictor has been developed by accomplishing the above four procedures, namely constructing a valid benchmark dataset, formulating protein samples with PseAAC to successfully catch their essential and core features, introducing a powerful and efficient algorithm or engine to operate the prediction, and achieving a high overall success rate by jackknife test on a stringent dataset in which none of the proteins included has ≥25% pairwise sequence identity to any other in the same subset (attribute category), it does not mean that the predictor has been really completed. This is because we are living in the Internet Age. To make a new prediction method really useful for the majority of people, it is an important direction or necessary procedure to provide a user-friendly and publicly accessible web-server for the method (Chou and Shen, 2009). Technically speaking, a web-server means a computer program that is responsible for accepting Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) requests from clients. By means of web-servers, many computational prediction methods, regardless how difficult their mathematics or how complicated their algorithms are, can be easily used by the vast majority of scientists to generate their desired data without the need to understand the mathematical details.

7. Conclusion and perspectives

In order to timely utilize the huge amount of newly discovered protein sequences generated in the postgenomic era for basic research and drug development, scientists are anxious to know their biological attributes. Many studies from various research laboratories around the world have indicated that mathematical analysis, computational modeling, and introducing novel physical concept to biology and medicine, such as graphical analysis (Andraos, 2008, Myers and Palmer, 1985, Zhou and Deng, 1984), modeling three-dimensional structures of targeted proteins/peptides for drug design (Sharma et al., 2008, Zhou and Troy, 2003, Zhou and Troy, 2005a, Zhou and Troy, 2005b, Zhou et al., 2004), diffusion-controlled reaction simulation (Zhou et al., 1981, Zhou and Zhong, 1982, Zhou et al., 1983), cellular responding kinetics (Qi et al., 2007), and biological functions of solitons in DNA (Zhou, 1989) can provide useful insights for both basic research and drug design and hence are widely welcome by science community. In view of this, it is highly desirable to develop automated methods by introducing new concepts and approaches for fast and accurately predicting the attributes of uncharacterized proteins based on their sequence information alone. During the past two decades or so, many statistical methods for predicting various protein attributes have been proposed. In this review, the key steps for establishing a powerful predictor in this regard have been analyzed in hopes that the points raised here may help stimulate the further development of new and more powerful predictors in this area. It is anticipated that the general form of PseAAC as formulated in this review may further stimulate the efforts to find various new modes of optimal PseAAC, which is one of the most important future directions we should focus on in order to substantially improve the power of predicting protein attributes.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professor Denise Kirschner and Dr. Dale Seaton of Elseivier for inviting him to write this review article. The author would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments in strengthening the presentation of this review.

References

- Altschul S.F. Evaluating the statistical significance of multiple distinct local alignments. In: Suhai S., editor. Theoretical and Computational Methods in Genome Research. Plenum; New York: 1997. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Anand A., Suganthan P.N. Multiclass cancer classification by support vector machines with class-wise optimized genes and probability estimates. J. Theor. Biol. 2009;259:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andraos J. Kinetic plasticity and the determination of product ratios for kinetic schemes leading to multiple products without rate laws: new methods based on directed graphs. Can. J. Chem. 2008;86:342–357. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T., Harris M.A., Hill D.P., Issel-Tarver L., Kasarskis A., Lewis S., Matese J.C., Richardson J.E., Ringwald M., Rubin G.M., Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Chou K.C. Nearest neighbour algorithm for predicting protein subcellular location by combining functional domain composition and pseudo-amino acid composition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;305:407–411. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Chou K.C. Predicting enzyme subclass by functional domain composition and pseudo amino acid composition. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:967–971. doi: 10.1021/pr0500399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Chou K.C. Predicting membrane protein type by functional domain composition and pseudo amino acid composition. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;238:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Li Y.X., Chou K.C. Using neural networks for prediction of domain structural classes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1476:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Liu X.J., Chou K.C. Artificial neural network model for predicting membrane protein types. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 2001;18:607–610. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2001.10506692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Zhou G.P., Chou K.C. Support vector machines for predicting membrane protein types by using functional domain composition. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3257–3263. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70050-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Zhou G.P., Chou K.C. Predicting enzyme family classes by hybridizing gene product composition and pseudo-amino acid composition. J. Theor. Biol. 2005;234:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., Pong-Wong R., Feng K., Jen J.C.H., Chou K.C. Application of SVM to predict membrane protein types. J. Theor. Biol. 2004;226:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.D., He J., Li X., Feng K., Lu L., Kong X., Lu W. Predicting protein subcellular locations with feature selection and analysis. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:464–472. doi: 10.2174/092986610790963654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call M.E., Wucherpfennig K.W., Chou J.J. The structural basis for intramembrane assembly of an activating immunoreceptor complex. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:1023–1029. doi: 10.1038/ni.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camon E., Magrane M., Barrell D., Lee V., Dimmer E., Maslen J., Binns D., Harte N., Lopez R., Apweiler R. The gene ontology annotation (GOA) database: sharing knowledge in uniprot with gene ontology. Nucl. Acids Res. 2004;32:D262-6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedano J., Aloy P., P'erez-Pons J.A., Querol E. Relation between amino acid composition and cellular location of proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:594–600. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chen L.X., Zou X.Y., Cai P.X. Predicting protein structural class based on multi-features fusion. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;253:388–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chen L., Zou X., Cai P. Prediction of protein secondary structure content by using the concept of Chou's pseudo amino acid composition and support vector machine. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:27–31. doi: 10.2174/092986609787049420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Zhou X., Tian Y., Zou X., Cai P. Predicting protein structural class with pseudo-amino acid composition and support vector machine fusion network. Anal. Biochem. 2006;357:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Tian Y.X., Zou X.Y., Cai P.X., Mo J.Y. Using pseudo-amino acid composition and support vector machine to predict protein structural class. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;243:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Kurgan L.A., Ruan J. Prediction of protein structural class using novel evolutionary collocation-based sequence representation. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1596–1604. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Feng K.Y., Cai Y.D., Chou K.C., Li H.P. Predicting the network of substrate–enzyme-product triads by combining compound similarity and functional domain composition. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:293. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Han K. BSFINDER: finding binding sites of HCV proteins using a support vector machine. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:373–382. doi: 10.2174/092986609787848153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.L., Li Q.Z. Prediction of apoptosis protein subcellular location using improved hybrid approach and pseudo amino acid composition. J. Theor. Biol. 2007;248:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. A novel approach to predicting protein structural classes in a (20-1)-D amino acid composition space. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 1995;21:319–344. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. The convergence–divergence duality in lectin domains of the selectin family and its implications. FEBS Lett. 1995;363:123–126. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00240-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. A key driving force in determination of protein structural classes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;264:216–224. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. Review: prediction of protein structural classes and subcellular locations. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2000;1:171–208. doi: 10.2174/1389203003381379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. Prediction of protein cellular attributes using pseudo amino acid composition. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 2001;43:246–255. doi: 10.1002/prot.1035. (Erratum: ibid., 2001, vol. 44, p. 60) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. Modelling extracellular domains of GABA-A receptors: subtypes 1, 2, 3, and 5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;316:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. Review: structural bioinformatics and its impact to biomedical science. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:2105–2134. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. Using amphiphilic pseudo amino acid composition to predict enzyme subfamily classes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:10–19. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C. Prediction of G-protein-coupled receptor classes. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:1413–1418. doi: 10.1021/pr050087t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Zhang C.T. A correlation coefficient method to predicting protein structural classes from amino acid compositions. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;207:429–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Zhang C.T. Predicting protein folding types by distance functions that make allowances for amino acid interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:22014–22020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Zhang C.T. Review: prediction of protein structural classes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995;30:275–349. doi: 10.3109/10409239509083488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Maggiora G.M. Domain structural class prediction. Protein Eng. 1998;11:523–538. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.7.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Elrod D.W. Protein subcellular location prediction. Protein Eng. 1999;12:107–118. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Using functional domain composition and support vector machines for prediction of protein subcellular location. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:45765–45769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Elrod D.W. Bioinformatical analysis of G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Proteome Res. 2002;1:429–433. doi: 10.1021/pr025527k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Predicting protein quaternary structure by pseudo amino acid composition. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 2003;53:282–289. doi: 10.1002/prot.10500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. A new hybrid approach to predict subcellular localization of proteins by incorporating gene ontology. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;311:743–747. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Prediction and classification of protein subcellular location: sequence-order effect and pseudo amino acid composition. J. Cellul. Biochem. 2003;90:1250–1260. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10719. (Addendum, ibid. 2004, vol. 91, p. 1085) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Predicting enzyme family class in a hybridization space. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2857–2863. doi: 10.1110/ps.04981104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Predicting protein structural class by functional domain composition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:1007–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.059. (Corrigendum: ibid., 2005, vol. 329, p. 1362) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Using GO-PseAA predictor to predict enzyme sub-class. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;325:506–509. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Prediction of protein subcellular locations by GO-FunD-PseAA predictor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;320:1236–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins by hybridizing functional domain composition and pseudo-amino acid composition. J. Cell Biochem. 2004;91:1197–1203. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Using GO-PseAA predictor to identify membrane proteins and their types. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2005;327:845–847. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Large-scale predictions of Gram-negative bacterial protein subcellular locations. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:3420–3428. doi: 10.1021/pr060404b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Predicting eukaryotic protein subcellular location by fusing optimized evidence-theoretic K-nearest neighbor classifiers. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:1888–1897. doi: 10.1021/pr060167c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Hum-PLoc: a novel ensemble classifier for predicting human protein subcellular localization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;347:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Predicting protein subcellular location by fusing multiple classifiers. J. Cell Biochem. 2006;99:517–527. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Cai Y.D. Predicting protein–protein interactions from sequences in a hybridization space. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:316–322. doi: 10.1021/pr050331g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Large-scale plant protein subcellular location prediction. J. Cell Biochem. 2007;100:665–678. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Euk-mPLoc: a fusion classifier for large-scale eukaryotic protein subcellular location prediction by incorporating multiple sites. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:1728–1734. doi: 10.1021/pr060635i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Review: recent progresses in protein subcellular location prediction. Anal. Biochem. 2007;370:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. MemType-2L: A WEB server for predicting membrane proteins and their types by incorporating evolution information through Pse-PSSM. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;360:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. ProtIdent: a web server for identifying proteases and their types by fusing functional domain and sequential evolution information. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;376:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Cell-PLoc: a package of web servers for predicting subcellular localization of proteins in various organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:153–162. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Review: recent advances in developing web-servers for predicting protein attributes. Natur. Sci. 2009;2:63–92. (openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/NS/) [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. A new method for predicting the subcellular localization of eukaryotic proteins with both single and multiple sites: Euk-mPLoc 2.0. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Cell-PLoc 2.0: an improved package of web-servers for predicting subcellular localization of proteins in various organisms. Natur. Sci. 2010;2:1090–1103. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.494. (openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/NS/) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Shen H.B. Plant-mPLoc: a top-down strategy to augment the power for predicting plant protein subcellular localization. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.C., Liu W., Maggiora G.M., Zhang C.T. Prediction and classification of domain structural classes. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 1998;31:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou P.Y. Prediction of protein structural classes from amino acid composition. In: Fasman G.D., editor. Prediction of Protein Structure and the Principles of Protein Conformation. Plenum Press; New York: 1989. pp. 549–586. [Google Scholar]

- Cover T.M., Hart P.E. Nearest neighbour pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theor. 1967;IT-13:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Denoeux T. A K-nearest neighbor classification rule based on Dempster-Shafer theory. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybernet. 1995;25:804–813. [Google Scholar]

- Diao Y., Ma D., Wen Z., Yin J., Xiang J., Li M. Using pseudo amino acid composition to predict transmembrane regions in protein: cellular automata and Lempel-Ziv complexity. Amino Acids. 2008;34:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H., Luo L., Lin H. Prediction of cell wall lytic enzymes using Chou's amphiphilic pseudo amino acid composition. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:351–355. doi: 10.2174/092986609787848045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.S., Zhang T.L., Chou K.C. Prediction of protein structure classes with pseudo amino acid composition and fuzzy support vector machine network. Protein Pept. Lett. 2007;14:811–815. doi: 10.2174/092986607781483778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P., Li Y. Prediction of protein submitochondria locations by hybridizing pseudo-amino acid composition with various physicochemical features of segmented sequence. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7:518. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P., Li Y. Prediction of C-to-U RNA editing sites in plant mitochondria using both biochemical and evolutionary information. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;253:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P., Cao S., Li Y. SubChlo: predicting protein subchloroplast locations with pseudo-amino acid composition and the evidence-theoretic K-nearest neighbor (ET-KNN) algorithm. J. Theor. Biol. 2009;261:330–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q.S., Jiang Z.Q., He W.Z., Li D.P., Chou K.C. Amino acid principal component analysis (AAPCA) and its applications in protein structural class prediction. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 2006;23:635–640. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2006.10507088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili M., Mohabatkar H., Mohsenzadeh S. Using the concept of Chou's pseudo amino acid composition for risk type prediction of human papillomaviruses. J. Theor. Biol. 2010;263:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Guo Y., Feng Y., Li M. Predicting DNA-binding proteins: approached from Chou's pseudo amino acid composition and other specific sequence features. Amino Acids. 2008;34:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng K.Y., Cai Y.D., Chou K.C. Boosting classifier for predicting protein domain structural class. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;334:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.E., Luo L.F. Use of tetrapeptide signals for protein secondary-structure prediction. Amino Acids. 2008;35:607–614. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R.D., Mistry J., Schuster-Bockler B., Griffiths-Jones S., Hollich V., Lassmann T., Moxon S., Marshall M., Khanna A., Durbin R., Eddy S.R., Sonnhammer E.L., Bateman A. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247-51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q.B., Ye X.F., Jin Z.C., He J. Improving discrimination of outer membrane proteins by fusing different forms of pseudo amino acid composition. Anal. Biochem. 2010;398:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q.B., Jin Z.C., Ye X.F., Wu C., He J. Prediction of nuclear receptors with optimal pseudo amino acid composition. Anal. Biochem. 2009;387:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Shao S.H., Xiao X., Ding Y.S., Huang Y.S., Huang Z.D., Chou K.C. Using pseudo amino acid composition to predict protein subcellular location: approached with Lyapunov index, Bessel function, and Chebyshev filter. Amino Acids. 2005;28:373–376. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou D.N., Karakasidis T.E., Nieto J.J., Torres A. Use of fuzzy clustering technique and matrices to classify amino acids and its impact to Chou's pseudo amino acid composition. J. Theor. Biol. 2009;257:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu F., Chen H. Evaluating long-term relationship of protein sequence by use of d-Interval conditional probability and its impact on protein structural class prediction. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:1267–1276. doi: 10.2174/092986609789071225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Ding Y.S., Zhang T.L. Prediction of G-Protein-coupled receptor classes in low homology using Chou's pseudo amino acid composition with approximate entropy and hydrophobicity patterns. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:559–567. doi: 10.2174/092986610791112693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Ding Y., Zhang T., Shen Y. Prediction of G-protein-coupled receptor classes with pseudo amino acid composition. Shengwu Yixue Gongchengxue Zazhi. 2010;27:500–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M.A., Clark J., Ireland A., Lomax J., Ashburner M., Foulger R., Eilbeck K., Lewis S., Marshall B., Mungall C., Richter J., Rubin G.M., Blake J.A., Bult C., Dolan M., Drabkin H., Eppig J.T., Hill D.P., Ni L., Ringwald M., Balakrishnan R., Cherry J.M., Christie K.R., Costanzo M.C., Dwight S.S., Engel S., Fisk D.G., Hirschman J.E., Hong E.L., Nash R.S., Sethuraman A., Theesfeld C.L., Botstein D., Dolinski K., Feierbach B., Berardini T., Mundodi S., Rhee S.Y., Apweiler R., Barrell D., Camon E., Dimmer E., Lee V., Chisholm R., Gaudet P., Kibbe W., Kishore R., Schwarz E.M., Sternberg P., Gwinn M., Hannick L., Wortman J., Berriman M., Wood V., de la Cruz N., Tonellato P., Jaiswal P., Seigfried T., White R. The gene ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D258-61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z.S., Zhang J., Shi X.H., Hu L.L., Kong X.G., Cai Y.D., Chou K.C. Predicting drug–target interaction networks based on functional groups and biological features. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T., Shi X.H., Wang P., He Z., Feng K.Y., Hu L., Kong X., Li Y.X., Cai Y.D., Chou K.C. Analysis and prediction of the metabolic stability of proteins based on their sequential features, subcellular locations and interaction networks. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahandideh S., Abdolmaleki P., Jahandideh M., Asadabadi E.B. Novel two-stage hybrid neural discriminant model for predicting proteins structural classes. Biophys. Chem. 2007;128:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahandideh S., Sarvestani A.S., Abdolmaleki P., Jahandideh M., Barfeie M. Gamma-turn types prediction in proteins using the support vector machines. J. Theor. Biol. 2007;249:785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahandideh S., Hoseini S., Jahandideh M., Hoseini A., Disfani F.M. Gamma-turn types prediction in proteins using the two-stage hybrid neural discriminant model. J. Theor. Biol. 2009;259:517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G., Wu X., Shen Y., Huang J., Quinn Li, Q. A classification-based prediction model of messenger RNA polyadenylation sites. J. Theor. Biol. 2010;265:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Wei R., Zhao Y., Zhang T. Using Chou's pseudo amino acid composition based on approximate entropy and an ensemble of AdaBoost classifiers to predict protein subnuclear location. Amino Acids. 2008;34:669–675. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Wei R., Zhang T.L., Gu Q. Using the concept of Chou's pseudo amino acid composition to predict apoptosis proteins subcellular location: an approach by approximate entropy. Protein Pept. Lett. 2008;15:392–396. doi: 10.2174/092986608784246443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandaswamy K.K., Pugalenthi G., Moller S., Hartmann E., Kalies K.U., Suganthan P.N., Martinetz T. Prediction of apoptosis protein locations with genetic algorithms and support vector machines through a new mode of pseudo amino acid composition. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:1473–1479. doi: 10.2174/0929866511009011473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S., Hauth A.M., Burger G. Function prediction of hypothetical proteins without sequence similarity to proteins of known function. Protein Pept. Lett. 2008;15:1107–1116. doi: 10.2174/092986608786071085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J.M., Gray M.R., Givens J.A. A fuzzy k-nearest neighbours algorithm. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1985;15:580–585. [Google Scholar]

- Klein P. Prediction of protein structural class by discriminant analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;874:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein P., Delisi C. Prediction of protein structural class from amino acid sequence. Biopolymers. 1986;25:1659–1672. doi: 10.1002/bip.360250909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V., Camon E., Dimmer E., Barrell D., Apweiler R. Who tangos with GOA?—use of gene ontology annotation (GOA) for biological interpretation of ‘-omics’ data and for validation of automatic annotation tools. In Silico Biol. 2005;5:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Copley R.R., Pils B., Pinkert S., Schultz J., Bork P. SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D257-60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M., Chothia C. Structural patterns in globular proteins. Nature. 1976;261:552–557. doi: 10.1038/261552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.M., Li Q.Z. Using pseudo amino acid composition to predict protein subnuclear location with improved hybrid approach. Amino Acids. 2008;34:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.M., Li Q.Z. Predicting protein subcellular location using Chou's pseudo amino acid composition and improved hybrid approach. Protein Pept. Lett. 2008;15:612–616. doi: 10.2174/092986608784966930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.C., Zhou X.B., Dai Z., Zou X.Y. Prediction of protein structural classes by Chou's pseudo amino acid composition: approached using continuous wavelet transform and principal component analysis. Amino Acids. 2009;37:415–425. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. The modified Mahalanobis discriminant for predicting outer membrane proteins by using Chou's pseudo amino acid composition. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;252:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Li Q.Z. Predicting conotoxin superfamily and family by using pseudo amino acid composition and modified Mahalanobis discriminant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;354:548–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Li Q.Z. Using pseudo amino acid composition to predict protein structural class: approached by incorporating 400 dipeptide components. J. Comput. Chem. 2007;28:1463–1466. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Ding H., Feng-Biao Guo F.B., Zhang A.Y., Huang J. Predicting subcellular localization of mycobacterial proteins by using Chou's pseudo amino acid composition. Protein Pept. Lett. 2008;15:739–744. doi: 10.2174/092986608785133681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Wang H., Ding H., Chen Y.L., Li Q.Z. Prediction of subcellular localization of apoptosis protein using Chou's pseudo amino acid composition. Acta Biotheor. 2009;57:321–330. doi: 10.1007/s10441-008-9067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W.Z., Xiao X., Chou K.C. GPCR-GIA: a web-server for identifying G-protein coupled receptors and their families with grey incidence analysis. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2009;22:699–705. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Yang J., Wang M., Xue L., Chou K.C. Using Fourier spectrum analysis and pseudo amino acid composition for prediction of membrane protein types. The Protein J. 2005;24:385–389. doi: 10.1007/s10930-005-7592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., He D., Yang S., Xu Y. Applying chemometrics approaches to model and predict the binding affinities between the human amphiphysin SH3 domain and its peptide ligands. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:246–253. doi: 10.2174/092986610790226085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Zheng X., Wang C., Wang J. Prediction of subcellular location of apoptosis proteins using pseudo amino acid composition: an approach from auto covariance transformation. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:1263–1269. doi: 10.2174/092986610792231528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Chou K.C. Prediction of protein structural classes by modified Mahalanobis discriminant algorithm. J. Protein Chem. 1998;17:209–217. doi: 10.1023/a:1022576400291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanobis P.C. On the generalized distance in statistics. Proc. Natl. Inst. Sci. India. 1936;2:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A., Anderson J.B., Derbyshire M.K., DeWeese-Scott C., Gonzales N.R., Gwadz M., Hao L., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Ke Z., Krylov D., Lanczycki C.J., Liebert C.A., Liu C., Lu F., Lu S., Marchler G.H., Mullokandov M., Song J.S., Thanki N., Yamashita R.A., Yin J.J., Zhang D., Bryant S.H. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D237-40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardia K.V., Kent J.T., Bibby J.M. Multivariate Analysis: Chapter 11 Discriminant Analysis; Chapter 12 Multivariate Analysis of Variance; Chapter 13 Cluster Analysis. Academic Press; London: 1979. pp. 322–381. [Google Scholar]

- Metfessel B.A., Saurugger P.N., Connelly D.P., Rich S.T. Cross-validation of protein structural class prediction using statistical clustering and neural networks. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1171–1182. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohabatkar H. Prediction of cyclin proteins using Chou's pseudo amino acid composition. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:1207–1214. doi: 10.2174/092986610792231564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S., Bhavna R., Mohan Babu R., Ramakumar S. Pseudo amino acid composition and multi-class support vector machines approach for conotoxin superfamily classification. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;243:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu C.B., Gonzalez-Diaz H., Magalhaes A.L. Enzymes/non-enzymes classification model complexity based on composition, sequence, 3D and topological indices. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;254:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murvai J., Vlahovicek K., Barta E., Pongor S. The SBASE protein domain library, release 8.0: a collection of annotated protein sequence segments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:58–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin A.G., Brenner S.E., Hubbard T., Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of protein database for the investigation of sequence and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers D., Palmer G. Microcomputer tools for steady-state enzyme kinetics. Bioinformatics (original: Computer Applied Bioscience) 1985;1:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima H., Nishikawa K. Discrimination of intracellular and extracellular proteins using amino acid composition and residue-pair frequencies. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;238:54–61. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima H., Nishikawa K., Ooi T. The folding type of a protein is relevant to the amino acid composition. J. Biochem. 1986;99:152–162. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni L., Lumini A. Genetic programming for creating Chou's pseudo amino acid based features for submitochondria localization. Amino Acids. 2008;34:653–660. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni L., Lumini A. A further step toward an optimal ensemble of classifiers for peptide classification, a case study: HIV protease. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:163–167. doi: 10.2174/092986609787316199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu B., Cai Y.D., Lu W.C., Zheng G.Y., Chou K.C. Predicting protein structural class with AdaBoost learner. Protein Pept. Lett. 2006;13:489–492. doi: 10.2174/092986606776819619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y.X., Zhang Z.Z., Guo Z.M., Feng G.Y., Huang Z.D., He L. Application of pseudo amino acid composition for predicting protein subcellular location: stochastic signal processing approach. J. Protein Chem. 2003;22:395–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1025350409648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielak R.M., Chou J.J. Solution NMR structure of the V27A drug resistant mutant of influenza A M2 channel. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;401:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai K.C.S. Mahalanobis D2. In: Kotz S., Johnson N.L., editors. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences, vol. 5. John Wiley & Sons.; New York: 1985. pp. 176–181. This reference also presents a brief biography of Mahalanobis who was a man of great originality and who made considerable contributions to statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Qi J.P., Shao S.H., Li D.D., Zhou G.P. A dynamic model for the p53 stress response networks under ion radiation. Amino Acids. 2007;33:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0454-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J.D., Huang J.H., Liang R.P., Lu X.Q. Prediction of G-protein-coupled receptor classes based on the concept of Chou's pseudo amino acid composition: an approach from discrete wavelet transform. Anal Biochem. 2009;390:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J.D., Huang J.H., Shi S.P., Liang R.P. Using the concept of Chou's pseudo amino acid composition to predict enzyme family classes: an approach with support vector machine based on discrete wavelet transform. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:715–722. doi: 10.2174/092986610791190372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt A., Hubbard T. Using neural networks for prediction of the subcellular location of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2230–2236. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]