Abstract

Infectious HIV‐1 requires gp160 cleavage by furin at the REKR511↓ motif (site1) into the gp120/gp41 complex, whereas the KAKR503 (site2) sequence remains uncleaved. We synthesized 41mer and 51mer peptides, comprising site1 and site2, to study their conformation and in vitro furin processing. We found that, while the previously reported 19mer and 13mer analogues represent excellent in vitro furin substrates, the present extended sequences require heparin for optimal processing. Our data support the hypothesis of a direct binding of heparin with site1 and site2, allowing selective exposure/accessibility of the REKR sequence, which is only then optimally cleaved by furin.

Keywords: HIV-1; human immunodeficiency virus type 1; GAGs, glycosaminoglycans; CD; circular dichroism; AIDS; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; RP-HPLC; reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography; PC; proprotein convertase; BTMD; before trans membrane domain; MS; mass spectrometry; AMC; 7-amino-4-methyl-coumarin; MCA; 7-amido-4-methylcoumarin; TFE; trifluoroethanol; SDS; sodium dodecyl sulfate; Tris–HCl; Tris-(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane–HCl; DMSO; dimethyl sulfoxide; HF; hydrofluoric acid; cmk; chloromethylketone; PBS; phosphate buffer saline; HIV-1; Furin; Heparin; Glycosaminoglycan; gp160; Processing

1. Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus type‐1 (HIV‐1) is the etiological agent for the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The envelope glycoprotein gp160 is processed by host proteases into the gp120/gp41 heterodimer. This allows the virus to infect target cells following the cell surface binding of the trimeric complex gp120/gp41 to the human CD4 receptor [1], and subsequently to the CXCR4/CCR5 co‐receptors [2, 3]. This interaction induces conformational change, which leads to the dissociation of gp120 from gp41, allowing the N‐terminal gp41 fusion peptide to be inserted into the host cell membrane [4]. Though the structures of a monomeric gp120 core in complex with the CD4 receptor/Fab 17b [5] and that of a post‐fusion form of gp41 were solved [6], little is known about the entire Env conformation. In fact, individually gp120 does not mimic its precursor conformation, as two monoclonal antibodies directed against the V3 loop recognized gp160, but not gp120 [7].

The Env precursor is cleaved by the proprotein convertase (PC) furin or furin like‐proteases at the REKR511↓ site1 [8], resulting in the fusogenic gp120/gp41 complex. Since the R511T mutation results in uncleaved gp160 and non‐infectious virus, cleavage is essential for viral entry [9]. In vitro investigations on peptides encompassing the gp120/gp41 junction confirmed that cleavage occurs at Arg511↓ [10]. Interestingly, upstream of the physiological processing site, a second site2 potential furin motif (KAKR503) is inefficiently cleaved. The exact role of site2 is unknown, though mutations of gp160 KAKR503 sequence result in an unprocessed precursor [11]. Conformational differences between site1 and site2 may explain the preference of furin for site1 [12].

Even though short gp160 peptides are efficiently cleaved in vitro by furin at Arg511, the full length gp160 was shown not to be efficiently cleaved ex vivo. This suggests that gp160 structure [11, 13], post‐translational modifications [14], as well as cellular and/or extracellular factors, may also influence the efficacy and selectivity of the furin mediated cleavage [15]. Viruses, such as Sindbis [16] and coronavirus [17], bind to target cells via cell‐surface glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Proteoglycans were also shown to facilitate HIV‐1 binding to and/or entry into cells lacking the CD4 receptor [18]. Moreover, enzymatic removal of cell surface heparan sulfate chains drastically impairs HIV‐1 infection of CD4+ cells [19]. This effect likely implicates gp160 and/or gp120 interaction with GAGs [20, 21, 22]. Many authors identified the binding site for heparin or its derivatives within the gp120 V3 loop [21]. However, an increasing body of evidence points to a possible gp160–GAGs interaction [22].

To investigate the influence of the sequence surrounding the REKR511 motif on gp160 processing efficiency, we synthesized various peptides derived from the gp120/gp41 junction (Table 1 ). Moreover, as a measure of the modulating role of GAGs on the furin processing, we evaluated the effect of heparin by both circular dichroism (CD) and HPLC. We found that the gp120/gp41 junction itself binds heparin, thus enhancing its furin processing.

Figure 1.

Table 1 Peptide sequences

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Peptide synthesis

The synthesis of the 14mer and 19mer was reported [10]. The 18mer, 41mer, and 51mer were synthesized on a semi‐automatic synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Mod. 431A) using a Rink amide MBHA resin (NovaBiochem, La Jolla, 0.48 mmol/g, 0.25 mmol), Boc chemistry and HBTU/HOBt activation. Detachment from the solid support and removal of the side chain protecting groups were achieved treating with HF:anisole:DMSO:2‐mercaptopyridine/10:1:1:1 (1 h, 0 °C). Crude products were purified by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP‐HPLC) on a Delta Pak HR C18 column (Waters, 6 μm, 60Å, 7.8 × 300 mm). Homogeneity grade was evaluated by RP‐HPLC on a Vydac C18 column (Waters, 5 μm, 300 Å, 4.6 × 250 mm). Molecular mass was checked by electrospray‐time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometry (MS; Mariner 5120 API‐TOF).

2.2. Circular dichroism

CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco CD spectropolarimeter Model J‐710 with a cylindrical fused quartz cell (path length 0.1 cm). The spectra are reported in units of mean ellipticity (peptide molecular weight/number of amide bonds), [Θ]R (deg cm2 dmol−1) or ellipticity, [Θ] (deg cm2). The measurements were performed in water, 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7, 14 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7, trifluoroethanol (TFE) 98%, 20 μM heparin (Sigma, low molecular weight) in 0.15 M NaCl + 25 mM Tris‐(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane–HCl (Tris–HCl) buffer pH 7, and in 0.15 M NaCl + 25 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7. Peptide concentrations, determined by amino acid analysis or UV absorption, varied from 18 to 43 μM. The spectra were corrected for the solvents, salts and heparin minor contributions.

2.3. Recombinant hfurin

The media of BSC40 cells infected with either wild type vaccinia virus (VV:WT, control) or a soluble form of hfurin (VV:hfurin‐BTMD) [8] were collected 18 h post‐infection and concentrated (Centriprep YM‐30). Activity was measured with the fluorogenic substrate Pyr‐RTKR‐MCA.

2.4. Enzymatic assays

Assays were performed in 100 μL at 37 °C on 100 μM peptide in 2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.0, 1 mM β‐mercaptoethanol, 2 μL furin (∼2 relative fluorescence units (RFU); where 1 RFU is defined as 1 pmol 7‐amino‐4‐methyl‐coumarin (AMC) released/min/μl enzyme acting on 100 μM of the fluorogenic substrate Pyr‐RTKR‐MCA) or as control 2 μL of media from VV:WT culture supernatant. When specified, incubation media also contained 2.5 μM, 20 μM or 25 μM heparin. Heparin alone shows no enzymatic activity (not shown). At various time points, 20 μL samples were analyzed by RP‐HPLC on a Varian C18 column (5 μm, 100 Å, 4.5 × 250 mm) and digestion products identified by mass spectrometry (MS). Percent cleavage was calculated from precursor areas.

2.5. Inhibition assays

Reactions, performed in 100 μL (25 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM β‐mercaptoethanol and 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.0) at 37 °C, contained 50 μM Pyr‐RTKR‐MCA or 100 μM 19mer as substrate, 2 μL of furin and different concentrations (1–100 μM) of the 18mer as inhibitor or 5 μM dec‐RVKR‐cmk [23]. Enzymatic activity with MCA‐conjugated peptidyl substrate was monitored (360 nm excitation, 460 nm emission) with a Spectra MAX GEMINI EM microplate spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices), in the presence or absence of either 20 μM or 100 μM heparin. Inhibition assays with the 19mer were monitored by RP‐HPLC. The IC50 were calculated using GraFit Version 4.09 software.

3. Results

3.1. Peptides design

Four peptides, 51mer, 41mer, 19mer and 13mer, spanning the gp160 cleavage sequence, were synthesized (Table 1). The 13mer containing site1, and the 19mer, which includes site1 and site2, were chosen as Ref. [10]. The extended 41mer and 51mer were synthesized to investigate the influence of the regions surrounding the physiological cleavage site on furin processing. It was reported that a cell‐permeable 22mer sequence KIEPLGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR511, which does not contain P′ residues, interferes with gp160 processing [24]. Thus, to test for a possible in vitro inhibitory function we also synthesized a 18mer peptide (LGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR511), mimicking the furin‐processing product of the 41mer (Table 1).

3.2. Circular dichroism

The spectra in phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and water showed a diagnostic band with a minimum at 198 nm, suggesting that the 51mer, 41mer and 19mer are unstructured (Fig. 1 A–C). In the presence of SDS, a red shift of the negative band was observed with a minimum at 201 nm for the 19mer (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, based on the 220 nm band intensity, the same micellar solution induced the 41mer and 51mer to assume a 20% and 21% α‐helix conformation respectively (Fig. 1B,C). This indicates a likely SDS interaction that could be due to the insertion of the hydrophobic C‐terminus into micelles and/or could result from the electrostatic binding of the positively charged site1 and/or site2 to the negatively charged micellar surface.

Figure 2.

CD spectra of: (A) 19mer, (B) 41mer, and (C) 51mer in (——) water, (‐ ‐ ‐ ‐ ‐) Phosphate buffer pH 7, (‐·‐·‐·‐) 14 mM SDS, and (– – –) 98%TFE/H2O; (D) water (black), 20 μM heparin (dark gray) in H2O and phosphate buffer pH 7.2 (light gray).

TFE induced order in the structure of the 19mer, 41mer, and 51mer (positive band at 190 nm, two negatives at 206 and 220 nm). The α‐helix content was 30% in 98% TFE/H2O for the 19mer, 59% for 41mer and 62% for 51mer (Fig. 1A–C).

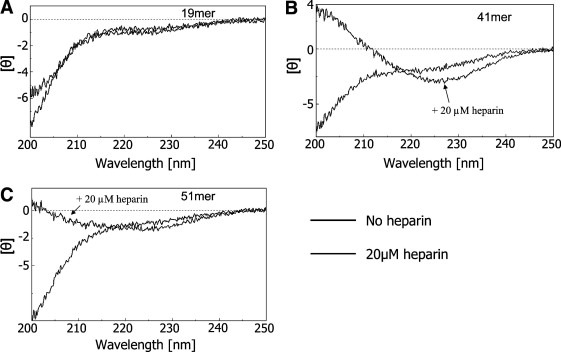

Since CD profiles in negatively charged SDS micellar solutions showed a transition of conformers towards a more structured population, and gp160 cleavage site is positively charged, further conformational investigations were performed. The CD profile of 20 μM heparin is similar to that of water (Fig. 1D) and that of the 19mer does change in the presence of heparin (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, the CD spectra of the 41mer and the 51mer were significantly modified in the presence versus absence of heparin (Fig. 2B,C). Similar results were obtained with higher heparin concentrations (100 μM).

Figure 3.

CD spectra of: (A) 19mer, (B) 41mer, and (C) 51mer in (black) 0.15 M NaCl and 25 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7, and (gray, arrow) 20 μM heparin in 0.15 M NaCl and 25 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.

3.3. Enzymatic assays

The 13mer and 19mer peptides were digested equally well by furin at site1 (Table 2, Table 3), showing complete processing at 5 h (Fig. 3A,B). In contrast, the 41mer and 51mer peptides were either barely or unprocessed, respectively, even after 24 h digestion at pH 7 (Fig. 4A,B; Tables 1–3). Since in vitro gp160 cleavage was reported to be optimal at pHs 6–7 [25], further assays were performed on the 41mer and 51mer at acidic conditions (pH 6.3, 6.7), again revealing no differences with respect to the results obtained at pH 7. Furthermore, similar data were observed in presence of low levels of denaturants (0.05% TX‐100 or SDS) (not shown).

Table 2.

Percent cleavage of the 13mer, 19mer, 41mer, and 51mer upon 2 h and overnight incubation in presence or absence of heparin

| Time incubation [h] | 13mer | 19mer | 41mer | 51mer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heparin | ||||||||

| – | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | |

| % Cleavage | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 2 | 53 | 54 | 59 | 52 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 8 |

| 6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Overnight | Traces | 40 | 0 | 60 | ||||

Table 3.

Fragments sequences derived from cleavage at site1 or site2 and their corresponding theoretical and experimental masses

| Precursor | Fragments sequence | Theoretical mass (Da) | Experimental mass (Da) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13mer | RVVQREKR | 1069.65 | 1070.26 |

| AVGIG | 415.24 | 415.27 | |

| 18mer | LGVAPTKAKR | 1069.65 | Undetectable |

| RVVQREKR | 1039.65 | Undetectable | |

| PTKAKRRVVQREKR | 1751.08 | 1751.16 | |

| 19mer | AVGIG | 415.24 | 415.27 |

| PTKAKR | 699.44 | Undetectable | |

| RVVQREKRAVGIG | 1466.88 | Undetectable | |

| LGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR | 2091.29 | 2091.30 | |

| 41mer | AVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAAS | 2039.06 | Undetectable |

| LGVAPTKAKR | 1039.65 | Undetectable | |

| RVVQREKRAVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAAS | 3090.69 | Undetectable | |

| YKYKVVKIEPLGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR | 3339.01 | Undetectable | |

| 51mer | AVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAAS | 2039.06 | Undetectable |

| YKYKVVKIEPLGVAPTKAKR | 2287.38 | Undetectable | |

| RVVQREKRAVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAAS | 3090.69 | Undetectable |

Figure 4.

RP‐HPLC profiles of: (A) 13mer digestion and (B) 19mer digestion obtained on a Varian C18 column with UV detector (214 nm). Arrows indicate the fragments.

Figure 5.

RP‐HPLC profiles of the digestion of the (A) 41mer and (B) 51mer obtained on a Varian C18 column with UV detector (214 nm). 20 μL of the enzymatic assay solution was taken (top) immediately after the addition of the substrate and upon overnight incubation (bottom). Arrows indicate the fragments, (∗) being LGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR for the 41mer and (∗∗) being AVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAAS.

We first hypothesized that product inhibition could explain these results. We thus tested the in vitro ability of the 18mer peptide, representing the furin‐derived product of the 41mer (Table 1), to inhibit the processing of either the fluorogenic Pyr‐RTKR‐MCA or the 19mer peptides. While the 18mer peptide effectively reduced the release of free AMC with an estimated IC50 of 1.6 μM (Fig. 5 A), it could only partially inhibit the 19mer processing with an IC50 > 100 μM (Fig. 5B). We conclude that product inhibition cannot explain the inability of furin to process the 41mer and 51mer peptides.

Figure 6.

Initial rate versus concentration of the 18mer to assess its effect on the furin cleavage of: (A) Pyr‐RTKR‐MCA, and (B) 19mer.

Because CD investigations showed a likely binding between heparin and the 41mer or 51mer (Fig. 2B,C), all four gp160‐derived analogues were digested overnight in the absence or presence of 2.5 μM heparin. Under these conditions, the 13mer and 19mer were digested at site1 with similar rates independent of the presence of heparin. In contrast, while no significant processing occurred in the absence of heparin, ∼40% and ∼60% processing at the REKR↓ site of the 41mer (into an 18mer product with identical retention time on RP‐HPLC to the synthetic version) and 51mer peptides, respectively, were observed in the presence of 2.5 μM heparin (Fig. 6 ). As control, we confirmed that the 41mer peptide is not cleaved by the recombinant VV:WT‐infected culture supernatant (Fig. 6, upper center panel). Furthermore, cleavage was inhibited by adding a well known PC‐inhibitor, dec‐RVKR‐cmk (Fig. 6, upper right panel) [23]. At 25 μM heparin we obtained a more extensive processing, but also noticed precipitation of the peptides (not shown). Finally, in a separate 6 h furin incubation experiment, the processing of the 41mer and 51mer peptides also showed a similar enhancement effect of heparin (not shown). In conclusion, these data indicate a likely heparin‐peptide interaction that may better expose site1, and hence allow more effective furin cleavage.

Figure 7.

Effect of heparin on the processing of the 41mer and 51mer. Upper panel controls: (left) RFU released versus time upon Pyr‐RTKR‐MCA cleavage by furin in (black) the absence, or presence of 20 μM (dark gray) or 100 μM (light gray) heparin; (upper central panel): incubation of the 41mer peptide with recombinant vaccinia WT‐infected culture supernatant (control); (upper right panel) effect of decanoyl‐RVKR‐cmk on the processing of the 41mer by furin. processing. Lower panels: 20 μL of the enzymatic assay solution containing 2.5 μM heparin was taken (top) immediately after the addition of the substrate and (bottom) after overnight incubation. Arrows indicate the fragments, (∗) being LGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR for the 41mer peptide or YKYKVVKIEPLGVAPTKAKRRVVQREKR for the 51mer peptide and (∗∗) being AVGIGALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAAS.

4. Discussion

Five peptides (Table 1) spanning the gp120/gp41 junction were investigated to better define the gp160 glycoprotein cleavage. The 19mer and its shorter analogue 13mer were processed by furin at site1 (REKR511), while site2 (KAKR503), which is included only in the 19mer, was uncleaved (Fig. 3). The lack of processing at site2 may be rationalized on the basis of structural motifs. In fact, the 19mer NMR molecular model in TFE revealed that site2 is embedded in a helical segment, whereas site1 is in a exposed loop at the C‐terminus of the peptide [12]. In contrast, the 41mer and 51mer, spanning extensive sequence of the gp160 cleavage region, were shown to represent very poor furin substrates. This suggests that the generated fragments could either act as inhibitors or that the more extended regions surrounding the physiological cleavage site prevents effective processing.

Since the possibility of product inhibition by the 18mer was excluded, we turned our attention towards structural restrictions and/or the need of other factors to rationalize the non‐cleavability of the 41mer and 51mer peptides. CD analysis on the 19mer, 41mer and 51mer in aqueous solution revealed that the three analogues are unstructured, and yet only the 19mer is digested by furin. Thus, some structural constraints must exist in the 41mer and 51mer, at least around site1. The same argument may explain the inability of furin to cleave at site2 in any substrates used. In an attempt to increase the 41mer and 51mer processing, we added some detergents to enhance the peptides backbone flexibility without affecting enzyme activity. However, neither TX‐100 nor SDS had any effect.

Therefore, we suspected that cellular/extracellular factors may influence the cleavability of gp160 by furin. Indeed, surface proteins containing heparin‐binding motifs processed by furin were reported [16, 26]. In particular, Sindbis virus attachment to target cells was enhanced in the presence of heparan sulfate (HS) via the furin recognition motif of the unprocessed envelope glycoprotein PE2 [16]. Similarly, peptides derived from the cleavage site of the human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion glycoprotein bind heparin and cellular GAGs [26]. Since the gp120/gp41 does not form stable trimers, while unprocessed gp160 does, it was hypothesized that gp160 oligomer attachment to the plasma membrane heparin sulfate occurs via its furin cleavage site [27]. Indeed, the K A KR 503 RVVQ R E KR 511 sequence exhibits a basic region, which contains two potential inverted consensus HS‐binding domains. Thus, it was shown that the affinity of gp160 for heparin is about 3‐times higher than that observed for gp120, implying that gp41 and/or hidden motifs in the mature gp120 may be involved in heparin binding [22].

CD spectra of the 41mer and 51mer suggest these peptides could interact with heparin (Fig. 2) and undergo structural reorganization. In fact, in presence of heparin, the profiles change with respect to those of the peptides alone. The negative band at 198 nm, diagnostic for aperiodic structures, is replaced by a positive one. In contrast, it is noteworthy that the shorter 19mer does not change its CD profile in the presence of heparin. Since the difference between the 41mer and the 19mer lies in 22 hydrophobic residues and the interaction between heparin and polypeptides is supposed to be electrostatic, these additional residues may support a favorable peptide conformation that optimally orients the positively charged side chains towards the negatively charged sulfate moieties. Our results agree with a probable glycosaminoglycans‐gp160 interaction, as proposed [22, 27], and suggest that the residues spanning the gp120/gp41 junction may contribute in gp160‐GAGs binding.

Moreover, given that heparin induces a change in the 41mer and 51mer conformation, which could play a key role in the enzyme‐substrate recognition, we analyzed how it may influence their furin processing. Surprisingly, while up to 100 μM heparin did not influence furin activity on Pyr‐RTKR‐MCA processing (Fig. 6, left upper panel), the 41mer and 51mer peptides were digested at site1 (Fig. 6). Therefore, we hypothesize that heparin induces conformational change, optimally exposing the furin‐cleavage REKR511 site. This is the first time that heparin is shown to enhance the in vitro cleavage of precursors by furin.

In conclusion, this study has shown that, in the absence of heparin, the 41mer and 51mer gp160 derived peptides represent very poor furin substrates in vitro, in contrast to the shorter analogues (13mer and 19mer) that are efficiently processed. Heparin was shown to strongly interact with the 41mer and 51mer peptides, inducing conformational changes, thereby exposing site1 for cleavage. Since the 41mer and 51mer peptides may not faithfully mimic the conformation around the cleavage site within the complete gp160 precursor, more analyses are required to assess if heparin is essential in vivo during gp160 maturation and how GAGs modulate HIV‐1 activity.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Brigitte Mary for her secretarial help. This work was supported by a CIHR grant (#MGP‐44363), a Canada Chair (#201652) and by a generous gift from the Strauss foundation.

Pasquato A.,Dettin M.,Basak A.,Gambaretto R.,Tonin L.,Seidah N.G. and Di Bello C.(2007), Heparin enhances the furin cleavage of HIV-1 gp160 peptides, FEBS Letters, 581, doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.050

References

- 1. Lifson J.D., Feinberg M.B., Reyes G.R., Rabin L., Banapour B., Chakrabarti S., Moss B., Wong-Staal F., Steimer K.S., Engleman E.G., Induction of CD4-dependent cell fusion by the HTLV-III/LAV envelope glycoprotein. Nature, 323, (1986), 725– 728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feng Y., Broder C.C., Kennedy P.E., Berger E.A., HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science, 272, (1996), 872– 877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dimitrov D.S., Fusin-a place for HIV-1 and T4 cells to meet. Nat. Med., 2, (1996), 640– 641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eckert D.M., Kim P.S., Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 70, (2001), 777– 810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kwong P.D., Wyatt R., Robinson J., Sweet R.W., Sodroski J., Hendrickson W.A., Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature, 393, (1998), 648– 659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan D.C., Fass D., Berger J.M., Kim P.S., Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell, 89, (1997), 263– 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinter A., Honnen W.J., Tilley S.A., Conformational changes affecting the V3 and CD4-binding domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 associated with env processing and with binding of ligands to these sites. J. Virol., 67, (1993), 5692– 5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vollenweider F., Benjannet S., Decroly E., Savaria D., Lazure C., Thomas G., Chretien M., Seidah N.G., Comparative cellular processing of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein gp160 by the mammalian subtilisin/kexin- like convertases. Biochem. J., 314, Pt 2 (1996), 521– 532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCune J.M., Rabin L.B., Feinberg M.B., Lieberman M., Kosek J.C., Reyes G.R., Weissman I.L., Endoproteolytic cleavage of gp160 is required for the activation of human immunodeficiency virus. Cell, 53, (1988), 55– 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brakch N., Dettin M., Scarinci C., Seidah N.G., Di Bello C., Structural investigation and kinetic characterization of potential cleavage sites of HIV GP160 by human furin and PC1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 213, (1995), 356– 361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bosch V., Pawlita M., Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env gene product proteolytic cleavage site. J. Virol., 64, (1990), 2337– 2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oliva R., Leone M., Falcigno L., D’Auria G., Dettin M., Scarinci C., Di Bello C., Paolillo L., Structural investigation of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp160 cleavage site. Chemistry, 8, (2002), 1467– 1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Travis B.M., Dykers T.I., Hewgill D., Ledbetter J., Tsu T.T., Hu S.L., Lewis J.B., Functional roles of the V3 hypervariable region of HIV-1 gp160 in the processing of gp160 and in the formation of syncytia in CD4+ cells. Virology, 186, (1992), 313– 317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reynard F., Fatmi A., Verrier B., Bedin F., HIV-1 acute infection env glycomutants designed from 3D model: effects on processing, antigenicity, and neutralization sensitivity. Virology, 324, (2004), 90– 102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Decroly E., Benjannet S., Savaria D., Seidah N.G., Comparative functional role of PC7 and furin in the processing of the HIV envelope glycoprotein gp160. FEBS Lett., 405, (1997), 68– 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ryman K.D., Klimstra W.B., Johnston R.E., Attenuation of Sindbis virus variants incorporating uncleaved PE2 glycoprotein is correlated with attachment to cell-surface heparan sulfate. Virology, 322, (2004), 1– 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Haan C.A., Li Z., Te L.E., Bosch B.J., Haijema B.J., Rottier P.J., Murine coronavirus with an extended host range uses heparan sulfate as an entry receptor. J. Virol., 79, (2005), 14451– 14456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Argyris E.G., Acheampong E., Nunnari G., Mukhtar M., Williams K.J., Pomerantz R.J., Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enters primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells by a mechanism involving cell surface proteoglycans independent of lipid rafts. J. Virol., 77, (2003), 12140– 12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel M., Yanagishita M., Roderiquez G., Bou-Habib D.C., Oravecz T., Hascall V.C., Norcross M.A., Cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediates HIV-1 infection of T-cell lines. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses, 9, (1993), 167– 174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrop H.A., Rider C.C., Heparin and its derivatives bind to HIV-1 recombinant envelope glycoproteins, rather than to recombinant HIV-1 receptor, CD4. Glycobiology, 8, (1998), 131– 137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Batinic D., Robey F.A., The V3 region of the envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 binds sulfated polysaccharides and CD4-derived synthetic peptides. J. Biol. Chem., 267, (1992), 6664– 6671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mbemba E., Czyrski J.A., Gattegno L., The interaction of a glycosaminoglycan, heparin, with HIV-1 major envelope glycoprotein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1180, (1992), 123– 129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garten W., Hallenberger S., Ortmann D., Schafer W., Vey M., Angliker H., Shaw E., Klenk H.D., Processing of viral glycoproteins by the subtilisin-like endoprotease furin and its inhibition by specific peptidylchloroalkylketones. Biochimie, 76, (1994), 217– 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barbouche R., Sabatier J.M., Fenouillet E., An anti-HIV peptide construct derived from the cleavage region of the Env precursor acts on Env fusogenicity through the presence of a functional cleavage sequence. Virology, 247, (1998), 137– 143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Willey R.L., Bonifacino J.S., Potts B.J., Martin M.A., Klausner R.D., Biosynthesis, cleavage, and degradation of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 envelope glycoprotein gp160. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 85, (1988), 9580– 9584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crim R.L., Audet S.A., Feldman S.A., Mostowski H.S., Beeler J.A., Identification of linear heparin-binding peptides derived from human respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein that inhibit infectivity. J. Virol., 81, (2007), 261– 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Staropoli I., Chanel C., Girard M., Altmeyer R., Processing, stability, and receptor binding properties of oligomeric envelope glycoprotein from a primary HIV-1 isolate. J. Biol. Chem., 275, (2000), 35137– 35145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]