Abstract

Polysubstituted pyrimidinylphosphonic and 1,3,5-triazinylphosphonic acids with potential biological properties were prepared in high yields by the microwave-assisted Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction of trialkyl phosphite with the corresponding halopyrimidines and halo-1,3,5-triazines, respectively, followed by the standard deprotection of the phosphonate group using TMSBr in acetonitrile. 4,6-Diamino-5-chloropyrimidin-2-ylphosphonic acid (7a) was found to exhibit a weak to moderate anti-influenza activity (28–50 μM) and may represent a novel hit for further SAR studies and antiviral improvement.

Keywords: Phosphonic acids; Pyrimidines; 1,3,5-Triazines; Microwave-assisted synthesis; Influenza virus

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Organophosphorus compounds have played an important role in the search for biologically important compounds.1 Among the family of phosphonic acids, those with a phosphorus atom directly attached to a carbon atom of six-membered nitrogen heterocycles have been studied for potential biological properties.

It was shown already in 1947 by Kosolapoff that the conventional Michaelis–Arbuzov (M–A) reaction is applicable for the synthesis of phosphonates from nitrogen heterocycles containing a halogen atom,2 and it was later used for the synthesis of dialkyl pyrimidylphosphonates and their free phosphonic acids.3

Analogously, the efficient synthesis of symmetric 1,3,5-triazine triphosphonic acid esters by the M–A reaction of cyanuric chloride with trialkyl phosphites has been reported either in the absence of solvent,4 or in toluene.5 Later it was shown that reactivity of various phosphorous esters in the M–A reaction decreases in the order of increasing electron-withdrawing effect of the substituents on the phosphorus atom.6 Furthermore, a replacement of the chlorine atom in 4,6-disubstituted 2-chlorotriazines was studied,7 and the M–A reaction was used to prepare a series of N,N′-bis[(dialkylphosphono)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl]diamines in high to moderate yields.

Generally, the synthesis of heteroarylphosphonates via the M–A reaction requires reflux of the halogen containing heterocycle with the corresponding trialkyl phosphite. Nevertheless, other methods of the phosphonic acid group introduction to the pyrimidine and purine bases exist. Phosphonate derivatives of uracil and adenine were prepared in poor yields (about 30%) by lithiation of the corresponding nucleobase derivative, followed by the reaction with diethyl chlorophosphate.8 The synthesis of (4,6-diamino-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)phosphonates through various cyclization reactions has also been reported.9

The Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction10 clearly is a method of choice for the preparation of heterocycles with directly attached phosphonate groups and this approach has recently been improved by the use of microwave irradiation.11

Microwave-assisted (MW-assisted) organic synthesis has been shown to provide a number of advantages over the standard heating techniques, such as clean reactions, improved reaction yields and shortened reaction times, easy work-ups and/or solvent-free reaction conditions.12

Recently, a preparation of phosphonates derived from 2(1H)-pyrazinone by Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction of halopyrazinones with triethyl phosphite has been reported.13 It was shown that compared to the conventional heating procedure, microwave irradiation reduces the reaction time dramatically (20 min compared to 12 h) while the MW-induction of side reactions lowered the reaction yields only slightly to moderately.13 The efficient synthesis of purine nucleosides and non-sugar nucleoside analogues containing a phosphonate group at the C-6 position of the purine moiety via MW-assisted Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction, starting from 6-chloropurine derivatives, has also been reported.14

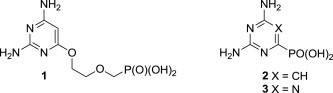

Recently, a novel class of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates (ANPs), the so called ‘open-ring’ analogues, with interesting antiviral (anti-HIV, anti-MSV and anti-HBV) properties has been discovered in which the pyrimidine base preferably contains an amino group(s) and the aliphatic phosphonate side chain linked to the C-6 position (e.g., PMEO derivative 1, Fig. 1 ).15 We were interested to reveal whether analogues with an eliminated acyclic chain in which the phosphonate moiety is directly attached to the nitrogen containing heterocycles (e.g., compounds 2 and 3, Fig. 1) would retain any antiviral activity.

Fig. 1.

Prototype of the ‘open-ring’ ANPs (1) and examples of the target analogues (2 and 3).

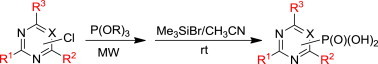

Herein we report on an efficient synthesis of polysubstituted pyrimidinyl- and 1,3,5-triazinylphosphonic and bisphosphonic acids using the MW-assisted Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction as the key reaction step.

2. Chemistry

Microwave-assisted organic synthesis has recently become a very rapidly developing area of chemistry.12 This progressive methodology provides a number of advantages over the standard heating techniques, like short reaction times, high yields, clean reactions and simple work-ups. Since we have recently developed an efficient MW-assisted synthesis of haloalkylphosphonates via the Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction,16 we have decided to employ this methodology for the synthesis of the desired polysubstituted pyrimidinyl- and 1,3,5-triazinylphosphonic acids as well.

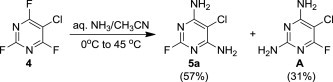

The starting polysubstituted pyrimidines and 1,3,5-triazines were either commercially available (compound 5e) or were prepared according to the published procedures (compounds 5b–d, Experimental section 5.3). Derivative 5a was easily obtained in 57% yield, together with its regioisomer A (31%), by careful ammonolysis of commercially available 5-chloro-2,4,6-trifluoropyrimidine (4, Scheme 1 ).

Scheme 1.

Ammonolysis of the compound 4.

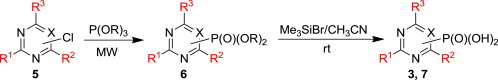

The treatment of the starting compounds 5a–e with an excess of triisopropyl phosphite (used as a solvent) under MW irradiation afforded the corresponding phosphonates 6a–e (entries 1–5, Scheme 2 , Table 1 ) in high yields (72–93%) and short reaction times (10–30 min). The dichloro derivatives 5c and 5e under these reaction conditions were converted to the corresponding bisphosphonates 6c and 6e, respectively (entries 3 and 5, respectively, Table 1). When the MW-assisted reaction of compound 5e was carried out at lower reaction temperature (190 °C compared to 200 °C) and shorter reaction time (20 min compared to 30 min), a mixture of the monophosphonate 6f (51%) and the bisphosphonate 6e (18%) was obtained, where the monosubstituted derivative was the major product (entry 6, Table 1).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the dialkyl ester phosphonates 6 and their corresponding phosphonic acids 3 and 7.

Table 1.

MW-assisted Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction for the synthesis of phosphonates 6

| Entry | Starting compounds | Phosphite | Conditions | Product | Yielda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

P(OiPr)3 | 200 °C, 30 min |  |

78% |

| 2 |  |

P(OiPr)3 | 120 °C, 20 min |  |

80% |

| 3 |  |

P(OiPr)3 | 150 °C, 10 min |  |

93% |

| 4 |  |

P(OiPr)3 | 220 °C, 30 min |  |

72% |

| 5 |  |

P(OiPr)3 | 200 °C, 30 min |  |

91% |

| 6 |  |

P(OiPr)3 | 190 °C, 20 min |  |

51%+6e (18%) |

| 7 |  |

P(OEt)3 | 160 °C, 20 min |  |

90% |

Isolated yields.

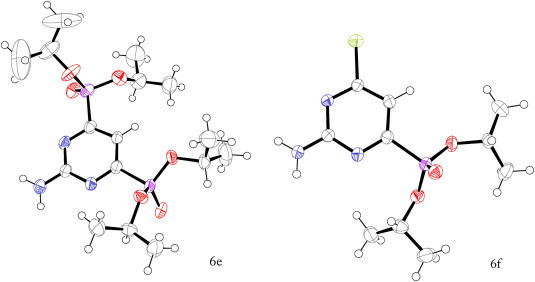

Since the compounds 6e and 6f were isolated as white crystals, the data from X-ray crystallography analysis were obtained to confirm the structure of these mono- and bis-substituted products of the Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

(a) ORTEP drawing of compound 6e. (b) ORTEP drawing of compound 6f. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Also, the treatment of the starting compound 5e with more reactive triethyl phosphite (instead of triisopropyl phosphite) afforded the expected bisphosphonate 6g quantitatively (90% of isolated product) under milder (160 °C and 20 min compared 200 °C and 30 min) MW-assisted reaction conditions (entry 7, Table 1).

The attempts to carry out the above described MW-assisted M–A methodology with the addition of a solvent were not successful. An addition of acetonitrile did not allow us to reach a high enough reaction temperature (200 °C) necessary for good conversion. An addition of DMF lead exclusively to an exchange of the chloro substituent for the dimethylamino group, which is in agreement with the recently published data.17

The diisopropyl esters 6a–e were treated with bromotrimethylsilane in acetonitrile at room temperature and the free phosphonic acids 3, 7a–c and 7e were isolated in high yields (80–87%) by our improved method using sonication of the crude phosphonic acid in 50% aqueous ethanol (Scheme 2).18

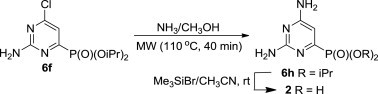

The target compound 2 was prepared by the MW-assisted ammonolysis of the chloro derivative 6f followed by the standard removal of the ester groups in the intermediate 6h using bromotrimethylsilane in acetonitrile (Scheme 3 ).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the diisopropyl ester 6h and its free phosphonic acid 2.

3. Biological activity

The final phosphonic acids 2, 3, 7a–c and 7e were evaluated for their antiviral properties. None of the heteroaryl phosphonic acids retained any antiretroviral properties of the ‘open-ring’ ANPs (e.g., compound 1, Fig. 1). Interestingly, 4,6-diamino-5-chloropyrimidin-2-ylphosphonic acid (7a) exhibited weak to moderate activity (28–50 μM) against influenza virus A with no toxicity (Table 2 ). Formation of suitable lipophilic prodrugs of compound 7a could potentially increase its antiviral effect due to a potential better cellular uptake (generally, up to 2–3 orders as in case of other ANPs). Phosphonic acid 7a can thus be considered as a new lead structure in search of novel anti-influenza agents and preparation of various prodrugs of 7a is currently in progress.

Table 2.

Antiviral and cytotoxic activity of the compound 7a against influenza viruses

| Compound | Cytotoxicity (μM) |

Anti-influenza EC50c (μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50a | MCCb | A (H1N1) | A (H3N2) | B | |

| 7a | >100 | >100 | 50±14 | 28±10 | 72±68 |

| Oseltamivir | >100 | >100 | 5.7±4.1 | 1.5±0.6 | 26.0±27.7 |

| Ribavirin | >100 | >100 | 9.2±0.8 | 8.7±3.8 | 5.6±2.8 |

| Amantadine | >100 | >100 | 36.8±2.6 | >200 | >200 |

| Rimantadine | >100 | >100 | 13.2±0.2 | >500 | >500 |

50% Cytostatic concentration or compound concentration required to reduce cell growth by 50% as measured by the cell viability staining of the cell cultures using MTS.

MCC or compound concentration required to cause a microscopically visible alteration of cell culture morphology.

50% Effective concentration or compound concentration required to inhibit virus-induced cytopathicity (CPE) by 50%, as scored by the cell viability staining of the cell cultures using MTS.

4. Conclusions

The microwave-assisted synthesis of polysubstituted pyrimidines and 1,3,5-triazines containing one or two phosphonic acid groups is described, starting from the easily available haloderivatives 5a–e. The halogen (chloro or fluoro) atoms were replaced by the dialkyl phosphonate group using the MW-assisted Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction, affording the corresponding heteroaryl phosphonic acids in good to excellent yields (72–93%) at short reaction times (10–30 min). The derivative 7a exhibits anti-influenza virus A activity in the middle micromolar range. Synthesis and biological evaluation of prodrugs and other derivatives of the candidate 7a will be published elsewhere.

5. Experimental

5.1. General experimental part

Unless otherwise stated, solvents were evaporated at 40 °C/2 kPa, and compounds were dried in vacuo over P2O5. Melting points were determined on a Büchi (Switzerland) melting point apparatus. NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE II 500 and/or Bruker AVANCE II 600 spectrometers in CDCl3, D2O or DMSO-d 6 (1H at 500.0 or 600.1 MHz and 13C at 125.7 or 150.9 MHz, chemical shifts are given in parts per million, coupling constants, J, in herz). Chemical shifts were referenced to TMS, to the solvent signal (δ 77.0 for CDCl3, 2.50 and 39.7 for DMSO) or to dioxane (δ 3.75 and 67.19). Mass spectra were measured on a LCQ Fleet spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using ESI ionisation. High resolution mass spectra were measured on a LTQ Orbitrap XL spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using ESI ionisation. IR spectra were recorded on an FTIR spectrometer Bruker IFS 55 (Equinox) in CHCl3 or KBr. All microwave irradiation experiments were carried out in the commercially available single-mode microwave synthesis apparatus equipped with a high sensitivity infrared sensor for temperature control and measurement (Discover LabMate, CEM Corporation) with continuous irradiation power from 0 to 300 W, pressure range 0–20 bar, 10 mL or 80 mL vials. The reactions were carried out in closed glass vials. The temperature was measured with an IR sensor on the outer surface of the reaction vials.

2-Amino-4,6-dichloropyrimidine, Me3SiBr, 2,4,6-trichloropyrimidine, 2-amino-4-chloro-6-hydroxypyrimidine, 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine, triethyl phosphite, triisopropyl phosphite and 5-chloro-2,4,6-trifluoropyrimidine were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich.

Acetonitrile was distilled from P2O5 and stored over molecular sieves (4 Å) in argon atmosphere. For column chromatography 230–400 (60 Å) mesh silica gel Merck grade 9385 (Sigma–Aldrich) was used as the stationary phase. All reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) aluminium sheets 20×20 cm Silica gel 60 F254 (Merck) in solvent systems S1 (10% MeOH/CHCl3) or S2 (isopropyl alcohol/saturated aqueous ammonia/water).

5.2. Single crystal X-ray structure analysis

The diffraction data of single crystals of 6e and 6f were collected on Xcalibur X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα (λ=1.54180 Å) at 150 K. The structures were solved by direct methods with SIR92,19 and refined by full-matrix least-squares on F with CRYSTALS.20 All hydrogen atoms were located in a difference map, but those attached to carbon atoms were repositioned geometrically and then refined with riding constraints, while all other atoms were refined anisotropically.

Crystal data for 6e (colourless, 0.06×0.15×0.42 mm): C16H31N3O6P2, monoclinic, space group P21/n, a=10.052(3) Å, b=20.408(5) Å, c=11.414(2) Å, β=100.42(2)°, V=2302.7(10) Å3, Z=4, M=423.39, 15,599 reflections measured, 4761 independent reflections. Final R=0.057, wR=0.063, GOF=1.115 for 2138 reflections with I>2σ(I) and 244 parameters. CCDC 839521.

Crystal data for 6f (colourless, 0.06×0.25×0.37 mm): C10H17Cl1N3O3P1, orthorhombic, space group Pccn, a=11.2805(9) Å, b=16.9325(15) Å, c=14.9789(15) Å, V=2861.1(4) Å3, Z=8, M=293.69, 35,952 reflections measured, 3044 independent reflections. Final R=0.048, wR=0.035, GOF=1.304 for 1716 reflections with I>2σ(I) and 163 parameters. CCDC 839520.

5.3. Synthesis of the starting compounds 5b–d

5.3.1. 4,6-Diamino-5-chloro-2-fluoropyrimidine (5a)

5-Chloro-2,4,6-trifluoropyrimidine (4, 0.10 mol, 16.9 g) was dissolved in acetonitrile (80 mL) at room temperature and the resulting mixture was cooled to 0 °C. An aqueous solution of ammonia (25%, 0.50 mol, 34 mL) was added dropwise under vigorous stirring during 2 h, while keeping the reaction temperature below 10 °C. When the addition was complete, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h and then heated to 45 °C for another 4 h. After cooling, the precipitated solid was filtered off, washed with a large amount of water and dried in vacuo at 50 °C. Chromatography on a silica gel column (chloroform/methanol) afforded 9.31 g (57%) of compound 5a as white solid; mp 249 °C, Rf (S1) 0.76. ESI+MS, m/z (%): 162 [M+] (100). δ H (DMSO-d 6) 6.90 (4H, br s, NH2); δ C (DMSO-d 6) 161.1 (d, J 20.4, C-4 and 6), 160.2 (d, J 202.7, C-2), 86.4 (d, J 6.9, C-5). For C4H4ClFN4 (162.01) calculated: 29.56% C, 2.48% H, 21.81% Cl, 11.69% F, 34.47% N; found: 29.37% C, 2.28% H, 22% Cl, 11.75% F, 34.29% N. As a second product was isolated 2,4-diamino-5-chloro-6-fluoropyrimidine (A): yield 5.10 g (31%), mp 208 °C, Rf (S1) 0.61. ESI+MS, m/z (%): 162 [M+] (100). δ H (DMSO-d 6) 6.99 (2H, br s, NH2), 6.51 (2H, br s, NH2); δ C (DMSO-d 6) 164.5 (d, J 232.6, C-6), 162.9 (d, J 5.7, C-4), 160.6 (d, J 23.2, C-2), 81.3 (d, J 31.7, C-5). For C4H4ClFN4 (162.01) calculated: 29.56% C, 2.48% H, 21.81% Cl, 11.69% F, 34.47% N; found: 29.80% C, 2.39% H, 22.00% Cl, 11.94% F, 34.21% N.

5.3.2. 2-Amino-6-chloro-5-nitropyrimidin-4(3H)-one (5b)21

Compound 5b was prepared according to the published procedure21 in 57% yield, mp >250 °C. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 189 [M−] (100).

5.3.3. 2-Amino-4,6-dichloro-1,3,5-triazine (5c)22

Compound 5c was prepared according to the published procedure22 in 72% yield, mp >250 °C. ESI+MS, m/z (%): 164 [M] (100). δ H (DMSO-d 6) 9.12 (2H, br s, NH2); δ C (DMSO-d 6) 169.4 (C-4 and 6), 167.1 (C-2).

5.3.4. 2,4-Diamino-6-chloro-1,3,5-triazine (5d)23

Compound 5d was prepared according to the published procedure23 in 71% yield, mp >250 °C. ESI+MS, m/z (%): 145 [M] (100). δ H (DMSO-d 6) 7.20 (2H, br s, NH2), 7.12 (2H, br s, NH2); δ C (DMSO-d 6) 166.8 (C-6), 167.3 (C-2 and 4).

5.4. Microwave-assisted Michaelis–Arbuzov reaction—general procedure

A mixture of starting pyrimidine or triazine (1.0 mmol) and triethyl or triisopropyl phosphite (5 mL) was sealed, flushed with argon and subsequently heated in a microwave reactor in a close-vessel mode at temperature and for a time period specific for each heterocyclic base 4a–e. After the reaction completion, excess of trialkyl phosphite was removed in vacuo and the desired product was isolated by column chromatography (chloroform/methanol—95/5). After evaporation of organics, the residue was sonicated in hexane (10 mL) for 5 min to form the desired product as a white precipitate.

5.4.1. Diisopropyl 4,6-diamino-5-chloropyrimidin-2-ylphosphonate (6a)

MW-assisted irradiation of 5a with triisopropyl phosphite at 200 °C for 30 min afforded 240 mg (78%) of 6a as white solid; mp 200–201 °C, Rf (S1) 0.53. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 307 [M−] (100). δ H (CDCl3) 6.07 (4H, br s, NH2), 4.79 (2H, d of septets, J 1′,P=7.6, J 1′,2′=6.2, H-1′), 1.40 (6H, d) and 1.30 (6H, d, J 6.2, H-2′); δ C (CDCl3) 159.1 (d, J 268.2, C-2), 158.4 (d, J 24.3, C-4 and 6), 93.2 (C-5), 71.9 (d, J 5.5, C-1′), 24.1 (d, J 3.8) and 23.7 (d, J 5.0, C-2′). For C10H18ClN4O3P (308.70) calculated: 38.91% C, 5.88% H, 18.15% N; found: 38.89% C, 5.86% H, 18.23% N.

5.4.2. Diisopropyl 2-amino-6-isopropoxy-5-nitropyrimidin-4-ylphosphonate (6b)

MW-assisted irradiation of 5b with triisopropyl phosphite at 120 °C for 20 min afforded 289 mg (80%) of 6b as white solid; mp 127–128 °C, Rf (S1) 0.64. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 361 [M−] (100). δ H (CDCl3) 5.97 (2H, br s, NH2), 5.35 (1H, septet, J 6.2, H-1″), 4.84 (2H, d of septets, J 1′,2′=6.2, J 1′,P=7.3, H-1′), 1.39–1.32 (18H, m, H-2′ and H-2″); δ C (CDCl3) 161.4 (d, J 11.3, C-6), 161.2 (d, J 26.3, C-2), 154.2 (d, J 222.2, C-4), 130.7 (d, J 17.0, C-5), 73.3 (d, J 6.4, C-1′), 72.2, (C-1″), 23.9 (d, J 4.0) and 23.5 (d, J 5.3, C-2′), 21.5 (C-2″). For C13H23N4O6P (362.32) calculated: 43.09% C, 6.40% H, 15.49% N; found: 43.33% C, 6.45% H, 15.27% N.

5.4.3. Tetraisopropyl 6-amino-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diyldiphosphonate (6c)

MW-assisted irradiation of 5c with triisopropyl phosphite at 150 °C for 10 min afforded 393 mg (93%) of 6c as white solid; mp 138–139 °C, Rf (S1) 0.80. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 423 [M−] (100). δ H (DMSO-d 6) 8.32 (2H, br s, NH2), 4.72 (4H, m, H-1′), 1.30 (12H, d) and 1.29 (12H, d, J 6.6, H-2′); δ C (DMSO-d 6) 171.7 (dd, 1 J 262.1, 3 J 14.9, C-2 and 4), 165.2 (t, J 18.1, C-4); 72.5 (m, C-1′), 24.1 (br s) and 23.7 (br s, C-2′). For C15H30N4O6P2 (424.37) calculated: 42.45% C; 7.13% H; 13.20% N; found: 42.50% C; 7.04% H; 13.07% N.

5.4.4. Diisopropyl 4,6-diamino-1,3,5-triazin-2-ylphosphonate (6d)

MW-assisted irradiation of 5d with triisopropyl phosphite at 220 °C for 30 min afforded 198 mg (72%) of 6d as white solid; mp 182–183 °C, Rf (S1) 0.47. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 274 [M−] (100). δ H (DMSO-d 6) 7.07 (2H, br s, NH2), 6.92 (2H, br s, NH2), 4.65 (2H, d of septets, J 1′,P=7.6, J 1′,2′=6.2, H-1′), 1.27 (6H, d) and 1.27 (6H, d, J 6.2, H-2′); δ C (DMSO-d 6) 171.1 (d, J 265.1, C-2), 166.4 (d, J 21.1, C-4 and 6), 71.3 (d, J 6.1, C-1′), 24.1 (d, J 3.6) and 23.8 (d, J 5.0, C-2′). For C9H18N5O3P (275.24) calculated: 39.27% C; 6.59% H; 25.44% N; found: 39.51% C; 6.78% H; 25.78% N.

5.4.5. Tetraisopropyl 2-aminopyrimidine-4,6-diyldiphosphonate (6e)

MW-assisted irradiation of 5e with triisopropyl phosphite at 200 °C for 30 min afforded 385 mg (91%) of 6e as white crystals; mp 103–104 °C, Rf (S1) 0.85. ESI+MS, m/z (%): 424 [M+] (24), 446 [M+Na] (100). δ H (CDCl3) 7.53 (1H, t, J 6.1, H-5), 5.93 (2H, br s, NH2), 4.81–4.88 (4H, m, H-1′), 1.40 (12H, d) and 1.32 (12H, d, J 6.2, H-2′); δ C (CDCl3) 163.6 (dd, 1 J 222.6, 3 J 7.9, C-4 and 6), 162.8 (t, J 23.3, C-2), 115.3 (t, J 21.8, C-5), 72.4 (m, C-1′), 24.0 (m) and 23.7 (m, C-2′). For C16H31N3O6P2 (423.38) calculated: 45.39% C, 7.38% H, 9.92% N, 14.63% P; found: 45.12% C, 7.40% H, 9.63% N, 14.95% P.

5.4.6. Diisopropyl 2-amino-6-chloropyrimidin-4-ylphosphonate (6f)

MW-assisted irradiation of 5e with triisopropyl phosphite at 190 °C for 20 min afforded 150 mg (51%) of 6f and 76 mg (18%) of 6e. Compound 6f is a white crystalline solid; mp 156–157 °C, Rf (S1) 0.55. ESI+MS, m/z (%): 294 [M+] (34), 316 [M+Na] (100). δ H (CDCl3) 7.10 (1H, d, J 7.0, H-5), 6.00 (2H, br s, NH2), 4.82 (2H, d of septets, J 1′,P=7.5, J 1′,2′=6.2, H-1′), 1.40 (6H, d) and 1.32 (6H, d, J 6.2, H-2′); δ C (CDCl3) 163.7 (d, J 172.3, C-4), 162.6 (m, C-2 and 6), 113.3 (d, J 23.0, C-5), 72.7 (d, J 6.1, C-1′), 23.9 (d, J 4.0) and 23.7 (d, J 4.9, C-2′). For C10H17ClN3O3P (293.69) calculated: 40.90% C, 5.83% H, 14.31% N, 10.55% P; found: 40.67% C, 5.80% H, 13.96% N, 10.81% P. The NMR and MS spectra of 6e are identical with those in Section 5.4.5.

5.4.7. Tetraethyl 2-aminopyrimidine-4,6-diyldiphosphonate (6g)

MW-assisted irradiation of 5e with triethyl phosphite at 160 °C for 20 min afforded 330 mg (90%) of 6g as white solid; mp 136–137 °C, Rf (S1) 0.81. ESI+MS, m/z (%): 368 [M+] (66), 390 [M+Na] (100). δ H (CDCl3) 7.54 (1H, t, J 6.2, H-5), 5.83 (2H, br s, NH2), 4.19–4.31 (8H, m, H-1′), 1.38 (12H, t, J 7.1, H-2′); δ C (CDCl3) 162.7 (t, J 23.3, C-2), 162.7 (dd, 1 J 222.0, 3 J 8.3, C-4 and 6), 115.6 (t, J 22.0, C-5), 63.5 (m, C-1′), 16.3 (m, C-2′). For C12H25N3O6P2 (369.12) calculated: 39.24% C, 6.31% H, 11.44% N, 16.87% P; found: 38.93% C, 6.26% H, 11.20% N, 16.98% P.

5.5. Diisopropyl 2,6-diaminopyrimidin-4-ylphosphonate (6h)

A mixture of 6f (1.0 mmol, 293 mg) in 1 M methanolic ammonia (5 mL) was irradiated in a MW instrument at 110 °C for 40 min in closed-vessel mode. Volatiles were evaporated and the residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (chloroform/methanol—95/5). After evaporation of fractions containing the desired product, the residue was sonicated in hexane (10 mL) for 5 min to give 240 mg (88%) of 6h as white solid, mp 238–239 °C, Rf (S1) 0.58. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 273 [M−] (100). IR (CHCl3, cell 0.118 mm) ν max (cm−1): 1003 (br s), 1246, 1388, 1569, 1635, 2986, 3182, 3309, 3415, 3529; δ H (CDCl3) 6.44 (1H, d, J 9.7, H-5), 4.73 (2H, d of septets, J 1′,P=7.5, J 1′,2′=6.2, H-1′), 1.39 (6H, d) and 1.32 (6H, d, J 6.2, H-2′); δ C (CDCl3) 163.8 (d, J 15.4, C-6), 162.6 (d, J 25.7, C-2), 157.5 (d, J 220.7, C-4), 100.6 (d, J 24.5, C-5), 71.9 (d, J 6.0, C-1′), 23.2 (d, J 4.1) and 22.9 (d, J 4.9, C-2′). For C10H19N4O3P (274.26) calculated: 43.79% C, 6.98% H, 20.43% N; found: 43.47% C, 6.96% H, 20.15% N.

5.6. Synthesis of phosphonic acids 2, 3, 7a–c and 7e—general procedure18

A mixture of dialkyl ester (0.5 mmol), acetonitrile (10 mL) and BrSiMe3 (1 mL, 7.6 mmol) was stirred overnight at room temperature. After evaporation in vacuo and codistillation with acetonitrile (2×10 mL), the residue was sonicated in 50% aqueous ethanol (20 mL) for 10 min. The mixture was evaporated to dryness in vacuo (45 °C, 2 mbar) and the residue was again sonicated in 50% aqueous ethanol (20 mL) for another 10 min. The white precipitate formed was filtered off and crystallized (water–ethanol) to afford the desired product as white crystals.

5.6.1. 2,6-Diaminopyrimidin-4-ylphosphonic acid (2)

Starting from 6h, yield 97 mg (86%); mp >250 °C, Rf (S2) 0.21. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 189 [M−] (100). δ H (D2O+NaOD) 6.33 (1H, d, J 8.7, H-5); δ C (D2O+NaOD) 165.7 (d, J 11.2, C-2 or 6), 161.4 (bd, J 173.0, C-4), 158.6 (br s, C-2 or 6), 99.8 (d, J 13.0, C-5). For C4H7N4O3P·2H2O (226.13) calculated: 21.25% C, 4.90% H, 24.78% N; found: 21.27% C, 5.18% H, 24.99% N.

5.6.2. 4,6-Diamino-1,3,5-triazin-2-ylphosphonic acid (3)

Starting from 6d, yield 76 mg (80%); mp >250 °C, Rf (S2) 0.17. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 190 [M−] (100). HR ESI-MS (composition of M−): C3H5O3N5P. δ C (D2O+NaOD) 181.3 (d, J 218.0, C-2), 166.7 (d, J 15.6, C-4 and 6). For C3H6N5O3P (191.09) calculated: 18.86% C; 3.16% H; 36.65% N; found: 19.15% C; 3.21% H; 36.52% N.

5.6.3. 4,6-Diamino-5-chloropyrimidin-2-ylphosphonic acid (7a)

Starting from 6a, yield 95 mg (85%); mp 221–223 °C, Rf (S2) 0.24. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 223 [M−] (100). IR (KBr, thin film) ν max (cm−1): 1199, 1228, 1647, 1662, 2749, 3149, 3350, 3487; δ C (D2O+NaOD) 169.3 (d, J 224.8, C-2), 159.1 (d, J 18.3, C-4 and 6), 93.0 (C-5). For C4H6ClN4O3P (224.54) calculated: 21.40% C; 2.69% H; 24.95% N; found: 21.33% C; 2.71% H; 24.73% N.

5.6.4. 2-Amino-6-isopropoxy-5-nitropyrimidin-4-ylphosphonic acid (7b)

Starting from 6b, yield 127 mg (81%); mp 246–248 °C, Rf (S2) 0.38. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 277 [M−] (100). δ H (D2O+NaOD) 5.35 (1H, septet, J 6.1, H-1′), 1.32 (6H, d, J 6.1, H-2′). δ C (D2O+NaOD) 166.6 (d, J 176.8, C-4), 162.3 (d, J 19.8, C-2), 161.7 (d, J 8.3, C-6); not found (C-5), 72.8 (C-1′), 21.5 (C-2′). For C7H11N4O6P·2H2O (314.19) calculated: 26.76% C, 4.81% H, 17.83 N%; found: 26.52% C, 4.75% H, 17.70% N.

5.6.5. 6-Amino-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diyldiphosphonic acid (7c)

Starting from 6c, yield 112 mg (87%); mp 232 °C (decomp.), Rf (S2) 0.10. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 255 [M−] (100). HR ESI-MS (composition of M−): C3H5O6N4P2. δ C (D2O+NaOD) 174.5 (dd, 1 J 220.2, 3 J 9.0, C-2 and 4), 165.6 (t, J 14.9, C-4). For C3H6N4O6P2 (256.05) calculated: 14.07% C; 2.36% H; 21.88% N; found: 14.20% C; 2.57% H; 21.62% N.

5.6.6. 2-Aminopyrimidine-4,6-diyldiphosphonic acid (7e)

Starting from 6e, yield 119 mg (87%); mp 248–250 °C, Rf (S2) 0.13. ESI-MS, m/z (%): 254 [M−] (100). IR (KBr, thin film) ν max (cm−1): 1092, 1273, 1579, 1677, 2249, 2669–2899 (br), 3138, 3277; δ H (D2O+NaOD) 7.43 (1H, t, J 6.3, H-5); δ C (D2O+NaOD) 167.7 (dd, 1 J 182.9, 3 J 6.1, C-4 and 6), 156.4 (t, J 15.4, C-2), 112.9 (t, J 15.1, C-5). For C4H7N3O6P2·H2O (273.08) calculated: 17.59% C, 3.22% H, 15.39% N; found: 17.30% C, 3.36% H, 15.62% N.

5.7. Antiviral assays

The antiviral assays [except anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) assays] were based on inhibition of virus-induced cytopathicity in HEL [herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2 (G), vaccinia virus and vesicular stomatitis virus], Vero (parainfluenza-3, reovirus-1, Coxsackie B4 and Punta Toro virus), HeLa (vesicular stomatitis virus, Coxsackie virus B4 and respiratory syncytial virus), MDCK (influenza A (H1N1; H3N2) and B virus) and CrFK (feline corona virus (FIPV) and feline herpes virus) cell cultures. Confluent cell cultures in microtiter 96-well plates were inoculated with 100 cell culture inhibitory dose-50 (CCID50) of virus (1 CCID50 being the virus dose to infect 50% of the cell cultures) in the presence of varying concentrations (5000, 1000, 200… nM) of the test compounds. Viral cytopathicity was recorded as soon as it reached completion in the control virus-infected cell cultures that were not treated with the test compounds.

The methodology of the anti-HIV assays was as follows: human CEM (∼3×105 cells/cm3) cells were infected with 100 CCID50 of HIV(IIIB) or HIV-2(ROD)/mL and seeded in 200 μL wells of a microtiter plate containing appropriate dilutions of the test compounds. After 4 days of incubation at 37 °C, HIV-induced CEM giant cell formation was examined microscopically. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) was defined as the compound concentration required to inhibit syncytia formation by 50%. The 50% cytostatic concentration (CC50) was defined as the compound concentration required to inhibit CEM cell proliferation by 50% in mock-infected cell cultures.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed as a part of Research Project Z40550506 of the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry. It was supported by the Grant Agency of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic through Project KJB400550903, by the Centre of New Antivirals and Antineoplastics 1M0508, by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic and by the Gilead Sciences. The research was supported by the K.U. Leuven (GOA 10/014). The authors thank Mrs. Leentje Persoons, Frieda De Meyer and Leen Ingels for excellent technical assistance for the antiviral assays.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.11.040. These data include MOL files and InChiKeys of the most important compounds described in this article.

Supplementary data

The following ZIP file contains the MOL files of the most important compounds referred to in this article.

ZIP file containing the MOL files of the most important compounds in this article.

References and notes

- 1.Engel R. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 1992. Handbook of Organophosphorus Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosolapoff G.M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947;69:1002. doi: 10.1021/ja01199a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosolapoff G.M., Roy C.H. J. Org. Chem. 1961;26:1895. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Morrison D.C. J. Org. Chem. 1956;22:444. [Google Scholar]; (b) Maxim C., Matni A., Geoffroy M., Andruh M., Hearns N.G.R., Clérac R., Avarvari N. New J. Chem. 2010;34:2319. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuo J.-D., Liu S.-M., Sheng Q. Molecules. 2010;15:7593. doi: 10.3390/molecules15117593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewertson W., Shaw R.A., Smith B.C. J. Chem. Soc. 1963:1670. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreher T., Costisella B., Kirschke K., Bartoszek M., Quaiser S., Fischer M. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1998;141:135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruyama T., Taira Z., Horikawa M., Sato Y., Honjo M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:2571. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Lu R., Yang H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5201. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hu F., Yang H. Synth. Commun. 2001;31:3817. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharya A.K., Thyagarajan G. Chem. Rev. 1981;81:415. For a review see: [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Kiddle J.J., Gurley A.F. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2000;160:195. [Google Scholar]; (b) Peyrottes S., Gallier F., Bejaud J., Perigaud C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7719. [Google Scholar]; (c) Peyrottes S., Gallier F., Papillaud A., Bejaud J., Perigaud C. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 2007;26:1513. doi: 10.1080/15257770701543049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gallier F., Peyrottes S., Perigaud C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:925. [Google Scholar]; (e) Sonkar R.K., Sarnaik D.A., Dikshit S.N., Saroj P.L., Huchche A.D. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008;45:199. [Google Scholar]

- 12.For recent reviews see:; (a) Lidström P., Tierney J.P., editors. Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Larhed M., Olofsson K., editors. Microwave Methods in Organic Synthesis. Springer; Berlin: 2006. [Google Scholar]; (c) Dallinger D., Kappe C.O. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:2563. doi: 10.1021/cr0509410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kappe C.O., Dallinger D., Murphree S. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2009. Practical Microwave Synthesis for Organic Chemists: Strategies, Instruments, and Protocols. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alen J., Dobrzańska L., De Borggraeve W.M., Compernolle F. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1055. doi: 10.1021/jo062176a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu G.-R., Xia R., Yang X.-N., Li J.-G., Wang D.-C., Guo H.-M. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2416. doi: 10.1021/jo702680p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Holý A., Votruba I., Masojídková M., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Naesens L., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:1918. doi: 10.1021/jm011095y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Balzarini J., Pannecouque C., De Clercq E., Aquaro S., Perno C.-F., Egberink H., Holý A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2185. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2185-2193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hocková D., Holý A., Masojídková M., Andrei G., Snoeck R., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:5064. doi: 10.1021/jm030932o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hocková D., Holý A., Masojídková M., Andrei G., Snoeck R., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:3197. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Balzarini J., Pannecouque C., Naesens L., Andrei G., Snoeck R., De Clercq E., Hocková D., Holý A. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 2004;23:1321. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200027573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ying C., Holý A., Hocková D., Havlas Z., De Clercq E., Neyts J. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1177. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1177-1180.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansa P., Holý A., Dračínský M., Baszczyňski O., Česnek M., Janeba Z. Green Chem. 2011;13:882. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Čechová L., Jansa P., Šála M., Dračínský M., Holý A., Janeba Z. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:866. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansa P., Kolman V., Kostinová A., Dračínský M., Mertlíková-Kaiserová H., Janeba Z. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2011;76:1187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altomare A., Cascarano G., Giacovazzo G., Guagliardi A., Burla M.C., Polidori G., Camalli M. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1994;27:435. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betteridge P.W., Carruthers J.R., Cooper R.I., Prout K., Watkin D.J. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:1487. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zorbach W.W., Tipson S.R. Vol. 1. Interscience, Wiley & Sons; USA: 1968. (Synthetic Procedures in Nucleic Acid Chemistry). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baliani A., Bueno G.J., Stewart M.L., Yardley V., Brun R., Barrett M.P., Gilbert I.H. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5570. doi: 10.1021/jm050177+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thurston J.T., Dudley J.R., Kaiser D.W., Hechenbleikner I., Schaefer F.C., Holm-Hansen D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951;73:2981. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ZIP file containing the MOL files of the most important compounds in this article.