Abstract

Hijacking and remodeling of host membranes is an obligatory step in the replicative cycle of (+)RNA viruses, including enteroviruses. Ilnytska et al. unveiled in Cell Host & Microbe that enteroviruses usurp clathrin-mediated endocytosis to shuttle cholesterol to sites of genome replication and that cholesterol is needed for efficient replication.

Positive-strand RNA [(+)RNA] viruses are a large and diverse group of viruses that include many important human pathogens, such as enteroviruses (including poliovirus, coxsackievirus, rhinovirus, enterovirus-71), hepatitis C virus (HCV), dengue virus, chikungunya virus, West Nile virus, norovirus, and SARS- and MERS-coronavirus. All (+)RNA viruses remodel host membranes into replication organelles (ROs), which support viral RNA synthesis, but the origin of the membranes varies between viruses [1]. Enteroviruses hijack membranes at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–Golgi interface to generate a complex tubulovesicular network 2, 3. Rather than using this cellular compartment as a whole, these viruses seem highly selective in recruiting specific host factors to build new organelles with a unique protein and lipid composition [1]. For example, enteroviruses, as well as HCV, specifically recruit the lipid-modifying kinase phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase IIIβ (PI4KIIIβ) to ROs for the production of PI4-phosphate (PI4P), an essential lipid for viral RNA replication [4]. Furthermore, poliovirus was recently shown to increase the uptake of fatty acids to use them for the highly upregulated synthesis of phosphatidylcholines, essential building blocks of membranes [5].

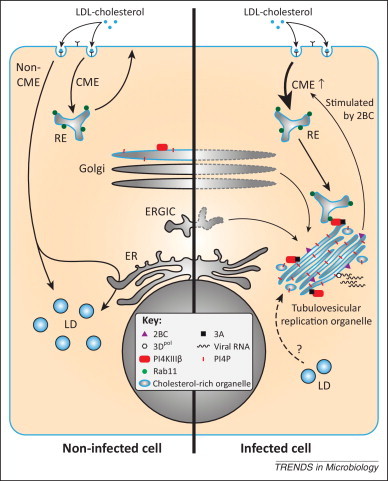

In the September issue of Cell Host & Microbe, the group of Nihal Altan-Bonnet unveiled that enteroviruses induce internalization of the plasma membrane and extracellular cholesterol pools and channel it towards the ROs [6]. Cholesterol is of vital importance for cellular membranes as it influences membrane fluidity and permeability as well as the formation of nanodomains called lipid rafts. Cells normally acquire cholesterol via de novo synthesis or through uptake of extracellular cholesterol. The plasma membrane is the largest source of free cholesterol (i.e., non-esterified) in most eukaryotic cells; and extracellular cholesterol is present in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) complexes that bind to the LDL receptor and are internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME). Free cholesterol is subsequently redistributed from the endosomal compartments to various organelles, while excess cholesterol is esterified with a fatty acid into cholesterylester and stored in lipid droplets (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Enteroviruses alter the cellular cholesterol landscape to support virus replication. In uninfected cells (left side), extracellular cholesterol from low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles and free cholesterol from the plasma membrane are taken up via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) and distributed to cellular membranes, e.g., via recycling endosomes (RE) to the plasma membrane. Cholesterol that enters via non-CME is stored in lipid droplets (LD) in a caveolin-dependent manner. In enterovirus-infected cells (right side), membranes from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) and the Golgi apparatus are remodeled into tubulovesicular replication organelles (ROs) that are rich in cholesterol. At these ROs, the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, 3Dpol, replicates the viral RNA. The viral protein 2BC enhances CME and cholesterol uptake (the fate of non-CME in infected cells is unknown and therefore not depicted). Following its normal route, endocytosed cholesterol is delivered into REs. Viral protein 3A mediates the recruitment of phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase IIIβ (PI4KIIIβ), which produces large amounts of phosphatidyl-4-phosphate (PI4P) lipids at the ROs. PI4KIIIβ in turn attracts cholesterol-rich REs through a direct interaction with the RE protein Rab11, resulting in the delivery of cholesterol to ROs. Consequently, storage of excess cholesterol in LDs is inhibited during enterovirus infection. It is remains to be established whether cholesterol stored in LDs is mobilized and shuttled to ROs as an additional source.

Although many viruses, including enteroviruses, require cholesterol for cell entry [7], the Altan-Bonnet laboratory now reports that modulation of the cellular cholesterol content affected replication of enteroviral RNA [6]. Viral RNA replication was reduced when the authors lowered free cholesterol levels by various treatments (e.g., depletion using methyl-β-cyclodextrin, or blocking uptake by pharmacological inhibition or knockdown of CME components). By contrast, replication was enhanced when cellular free cholesterol was elevated (e.g., by knockdown of the non-CME component caveolin or in cells from Niemann-Pick Type C disease patients). In addition, they show that enteroviruses actively increased CME to stimulate the uptake of cholesterol from the medium (Figure 1). Concomitantly, the amount of cholesterylester, which reflects the amount of cholesterol stored in lipid droplets, decreased during infection. It remains to be determined whether enteroviruses merely inhibited the deposition of new cholesterylesters in lipid droplets by subverting free cholesterol to ROs, or whether they mobilized stored cholesterol from lipid droplets as a source of free cholesterol in addition to the increased uptake of cholesterol. Collectively, these data convincingly demonstrate that uptake of cholesterol and delivery to ROs is important for enterovirus genome replication.

The authors then wondered how enteroviruses achieved the enhanced endocytosis of cholesterol. The most likely candidates for this effect are viral proteins 2B and/or 2BC, which were previously shown to increase uptake of cell surface proteins [8]. The Altan-Bonnet laboratory demonstrated that ectopic expression of 2BC alone was sufficient to increase uptake of the endocytic marker AM4-65 and to raise cellular free cholesterol levels, pointing to an important role of 2B (which was not tested) and/or 2BC in the enhanced uptake of cholesterol in infected cells. But how is the endocytosed cholesterol subsequently channeled to ROs? Normally, recycling endosomes (REs) transport a portion of the internalized cholesterol back to the plasma membrane. The authors show that in infected cells REs are re-routed to the replication sites, making them a likely supplier of cholesterol. The viral protein 3A plays an important role in this re-routing by recruiting PI4KIIIβ [4], which directly binds the RE protein Rab11 (Figure 1). It remains to be established whether cholesterol is delivered to ROs by fusion of REs (or RE-derived vesicles) with ROs, or whether cholesterol is shuttled between RE- and RO-membranes by cellular (chole)sterol transfer proteins.

Recently, single point mutations in the enteroviral protein 3A were found to allow genome replication in the absence of PI4KIIIβ 9, 10. A burning question is now whether these 3A mutations also allow cholesterol-independent replication, or whether the mutant viruses use a different mechanism to recruit cholesterol to ROs.

Having found that cholesterol is required at ROs, the authors set out to elucidate the role of cholesterol in replication and found that cholesterol affected the proteolytic processing of the viral protein 3CDpro [6]. Upon delivery in the cytoplasm, the enteroviral genome is initially translated into a single polyprotein that is subsequently stepwise cleaved by viral proteases (i.e., 2Apro, 3Cpro, 3CDpro) to generate the individual viral proteins. One of the cleavage intermediates is 3CDpro, which functions in RO formation, viral RNA synthesis, and cleavage of the viral capsid precursor protein. Upon autocleavage, 3CDpro is cleaved into 3Cpro and 3Dpol, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase that replicates the viral genome. The Altan-Bonnet group observed that depletion of cholesterol enhanced cleavage of 3CDpro, but not of intermediates 2BC and 3AB [6]. How cholesterol influences the efficiency of 3CDpro cleavage at the RO and whether the altered cleavage efficiency of 3CDpro is indeed critical for optimal virus replication are topics for future investigation. Furthermore, it remains to be established whether there are any additional roles for cholesterol at ROs. Given its profound effects on membrane fluidity, permeability, and lipid raft formation, it will be interesting to study whether the cholesterol content is important for the generation and/or architecture of the tubulovesicular RO network.

In conclusion, Altan-Bonnet and colleagues elegantly show that enteroviruses remodel the host cell cholesterol landscape for building ROs and efficient viral RNA replication.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO-VENI-863.12.005 to H.M.vdS., NWO-VENI-722.012.006 to J.R.P.S., NWO-VICI-91812628 to F.J.M.vK.) and the European Union Seventh Framework Program (EUVIRNA Marie Curie Initial Training Network, grant agreement number 264286) to F.J.M.vK.

References

- 1.Belov G.A., Van Kuppeveld F.J. (+)RNA viruses rewire cellular pathways to build replication organelles. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limpens R.W.A.L. The transformation of enterovirus replication structures: a three-dimensional study of single- and double-membrane compartments. MBio. 2011;2 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00166-11. e00166–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belov G.A. Complex dynamic development of poliovirus membranous replication complexes. J. Virol. 2012;86:302–312. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05937-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu N-Y. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell. 2010;141:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nchoutmboube J.A. Increased long chain acyl-CoA synthetase activity and fatty acid import is linked to membrane synthesis for development of picornavirus replication organelles. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003401. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilnytska O. Enteroviruses harness the cellular endocytic machinery to remodel the host cell cholesterol landscape for effective viral replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorizate M., Krausslich H.G. Role of lipids in virus replication. In: Simons K., editor. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2011. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornell C.T. Coxsackievirus B3 proteins directionally complement each other to downregulate surface major histocompatibility complex class I. J. Virol. 2007;81:6785–6797. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Schaar H.M. Coxsackievirus mutants that can bypass host factor PI4KIIIbeta and the need for high levels of PI4P lipids for replication. Cell Res. 2012;22:1576–1592. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arita M. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III beta is a target of enviroxime-like compounds for antipoliovirus activity. J. Virol. 2011;85:2364–2372. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02249-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]