Abstract

We recently reported the successful use of the loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) reaction for hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA amplification and its optimal primer design method. In this study, we report the development of an integrated isothermal device for both amplification and detection of targeted HBV DNA. It has two major components, a disposable polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) micro-reactor and a temperature-regulated optical detection unit (base apparatus) for real-time monitoring of the turbidity changes due to the precipitation of DNA amplification by-product, magnesium pyrophosphate. We have established a correlation curve (R2 = 0.99) between the concentration of pyrophosphate ions and the level of turbidity by using a simulated chemical reaction to evaluate the characteristics of our device. For the applications of rapid pathogens detection, we also have established a standard curve (R2 = 0.96) by using LAMP reaction with a standard template in our device. Moreover, we also have successfully used the device on seven clinical serum specimens where HBV DNA levels have been confirmed by real-time PCR. The result indicates that different amounts of HBV DNA can be successfully detected by using this device within 1 h.

Keywords: LAMP, Isothermal, Diagnostic device, Hepatitis B virus

1. Introduction

Around the world, the hepatitis B virus is one of the most common viral pathogens, having infected more than 370 million people [1]. At present, serologic diagnosis of HBV infections is based on the viral antigens and antibodies. However, the REVEAL-HBV (risk evaluation of viral load elevation and associated liver disease/cancer-hepatitis B virus) study indicates that the serum level of HBV DNA (≧10,000 copies/ml) is a strong risk predicator of hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis [2], [3]. It would thus be clinically valuable to have a molecular diagnostic method for screening and monitoring the progress of hepatitis. However, the long reaction time of traditional PCR amplification and the high cost of thermalcycler are still major issues for such a screening application. Therefore, it is important to develop a rapid and accurate diagnostic device for field applications as soon as possible [4].

Even though many nucleic acid amplification methods are currently available, a low cost, yet rapid method would be extremely useful, especially in developing countries. There are several PCR-based amplification methods [5], such as nucleic acid sequence-based amplification [6] and self-sustained sequence replication, for nucleic acid amplification. However, these methods require a precise instrument to provide the efficient thermal cycles and to shorten the total amplification time for a test run. In general, it takes up to 2.5 h for a PCR test with the present state of art equipment. Alternatively, isothermal amplification methods, e.g., strand displacement amplification [7], branched DNA amplification, invader, rolling circle amplification [8] and loop-mediated amplification method (LAMP) [9], have been proposed for amplifying the targeted nucleic acid sequence under a single working temperature condition with special designs for the buffer system and primers to prevent non-specific amplification. It would thus allow for the development of a low-cost device for rapid pathogen detection.

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), originally developed by Notomi et al. [9], utilizes a designed set of six primers, termed inner and outer primers, to recognize specific gene sequences, and a polymerase with strand displacement activity to generate large amounts of amplified product (>109 copies) within 1 h [10]. Moreover, it has been shown that the well-known PCR inhibitors in the blood (e.g., heme) have little impact on the LAMP reactions [11]. It is believed that the Bacillus stearothermophilus (Bst) DNA polymerase used in the LAMP reactions is more resistant to these inhibitors. Therefore, the LAMP reaction has been successfully applied for fast genetic screening tests in many acute infectious diseases, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis [12], severe acute respiratory syndrome virus [13], human influenza viruses [14], [15], avian influenza viruses [16] and herpes viruses [17], [18], with special primer design and buffer adjustment. Among these, the LAMP method has been shown to have great promise for the amplification of HBV DNA. In addition, the DNA yield of the LAMP reaction (10 μg/25 μl) is much higher than that of the traditional PCR (0.2 μg/25 μl) [19]. Recently, we have successfully demonstrated that the level of turbidity, which is due to the by-product (magnesium pyrophosphate) of DNA polymerization, has a high correlation to the amounts of amplified DNA. Then, we decided to work with a total of 25 μl of LAMP reaction volume because of the practical limitations of turbidity detection. In addition to the use of the LAMP protocol, we have adapted a simulated chemical reaction to mimic the by-product production without using expensive polymerase and primers [20]. It can serve as an internal quality check for the system validation. Therefore, it is our intention to design and implement a compact integrated device with a disposable chip and simple quantitative optical read-out for low-cost applications.

In this study, the goal is to develop an integrated isothermal device for real-time detection of HBV viral DNA via the LAMP amplification method. It has two major components, a disposable PMMA micro-reactor and a temperature-regulated optical detection unit (base apparatus) for real-time monitoring of the turbidity changes due to precipitation of DNA amplification by-product, magnesium pyrophosphate. We decided to work with a total of 25 μl of LAMP reaction volume after adding 2 μl of DNA sample because of the practical limitations of turbidity detection. The performance of this integrated isothermal device has been tested by using within and between runs. For the applications of rapid pathogens detection, we have successfully used the device on seven clinical serum specimens and confirmed HBV DNA levels with real-time PCR. The results of using this device indicate that different amounts of HBV DNA can be successfully detected within 1 h with a threshold level of 10,000 copies/ml, which is the recommendatory quantity of REVEAL-HBV study. This integrated isothermal device can be advantageous in a wide spectrum of field applications, including pathogen detection and gene testing.

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of primers for LAMP reaction

The design methodology of primers used has been discussed in our previous study [21]. In brief, the target DNA sequences and the partial HBV polymerase gene sequences are collected from a public data base and then aligned to find highly conserved fragments. Then, the primer design can be executed by using the available software, Gene Runner (Hastings Software, Inc., Hudson, NY, USA), to check design parameters. The melting temperature (T m) of each primer is calculated by the nearest-neighbor T m theory. Finally, the designed primers are synthesized by the contract services (Quality Systems, Inc., Taipei City, Taiwan, ROC) followed by having its concentration optimized with a reaction buffer in the amplified test. The partial HBV polymerase gene was directly cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (PROMEGA, Madison, WI, USA) as standard template DNA. The LAMP assay was performed in a total of 25 μl of the mixtures, which contain 20 pmol each of IB-FIP (5′-TGGAATTAGAGGACAAACGGGTGCTGCTATGCCTCATCTT-3′) and IB-BIP (5′-GCTCAAGGAACCTCTATGTTTCGATGATGGGATGGGAATACA-3′), 5 pmol each of IB-F3 (5′-GGCGTTTTATCATCTTCCT-3′) and IB-B3 (5′-AGGTTACTTGCGAAAGCC-3′), 10 pmol each of IB-loopF (5′-TACCTTGATAGTCCAGAAGAACC-3′) and IB-loopB (5′-CTACGGACGGAAACTGCAC-3′), 0.4 mM dNTPs, 1 M betaine, 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 6 mM MgSO4, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 units of the Bst DNA polymerase large fragment (NEW ENGLAND BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), and 2 μl of DNA standard template—a partial HBV polymerase gene cloned into a pGEM-T easy vector or purified DNA. We utilized a set of six primers to recognize specific HBV gene sequences. This mixture was incubated in a Mastercycler® gradient PCR machine (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) or our miniaturized device at 65 °C for 1 h. The white precipitate of reaction by-product can be observed by naked eye. Aliquots of 2.5 μl of LAMP products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels (1× TBE) and then stained with SYBR Green I dye for verification by fluorescent imager (GelDoc-It Imaging System, UVP, Upland, CA, USA). In addition, the sequences of LAMP product were confirmed by the ABI 3100-avant DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA).

2.2. The integrated isothermal device

Our integrated isothermal device has two major components, a disposable polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) micro-reactor and a temperature-regulated optical detection unit (base apparatus) for real-time monitoring of the turbidity changes due to the precipitation of DNA amplification by-product, magnesium pyrophosphate. The disposable micro-reactor is constructed from two PMMA parts to create a reaction chamber of 5-mm optical path length by using UV-light curing adhesives (ultrawide GN150, Everwide Chemical Company, Yunlin County, Taiwan, ROC). For the LAMP reaction, the reaction chamber is filled with 25 μl reagent manually via micropipette and then is sealed with gluey aluminum foil. The base apparatus consists of an optical detection unit, a thin-film heater, a temperature controller, and a power supply. The optical detection unit (FS-V21G, KEYENCE Corporation, Osaka, Japan) employs a light emitting diode (LED) light source at 533 nm and a phototransistor detector with an extension of collimated optical fibers for the collection of forward scattering light. The temperature controller has a 60 W power supply and two 2 in. × 2 in. thin-film Kapton™ heaters (Minco, Minneapolis, MN, USA), which is controlled by a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller (ANLY Electronics, Taipei County, Taiwan, ROC) with one thermal coupler feedback. After the insertion of assembled micro-reactor chips into the base apparatus, we can initiate the HBV LAMP reaction at 65 °C through out the whole experimental time course. At the same time, the scattering light intensity is measured by the optical detection unit. In general, turbidity refers to the scattering of light by particles and has to be measured and calculated indirectly from Eq. (1) [22] assuming no absorption in the path length:

| (1) |

where I 0 is the intensity of incident light and I 1 is the intensity of transmitted light.

2.3. Simulated precipitation reaction for control experiment

During the DNA polymerization process, white precipitation of magnesium pyrophosphate will be produced in the presence of magnesium ions and pyrophosphate ions as shown in the following equations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Instead of using dNTP and DNA polymerases to initiate the precipitation, we have adapted a simulated reaction, as shown in Eq. (4), to mimic the production of magnesium pyrophosphate which is used for evaluating the performance of our device:

| (4) |

This reaction is performed in a total of 1 ml solution containing the following reagents, 1× Thermolpol buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1% Triton X-100), 2 mM MgSO4, gradient concentrations of K4P2O7 or K3PO4 from 1.2 to 0.2 mM and double-distilled water. The mixture is incubated in the disposable micro-reactor at 65 °C for 1 h to measure the end-point turbidity by our system. In addition, this experimental result was confirmed by a UV–visible spectrometer (VARAIN, Palo Alto, CA, USA) at 533 nm. It also can be used to establish the correlation curve between the concentration of pyrophosphate ions and the level of turbidity.

2.4. Preparation of clinical serum specimens

A series of seven serum specimens were obtained from patients at National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). The serum HBV viral DNA was extracted by using the QIAamp Viral DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). Briefly, 800 μl of viral particles lysis buffer (AVL buffer) was mixed with 200 μl of serum. The AVL buffer will lyse viral particles under highly denaturing conditions to inactivate DNases and to provide optimum binding buffering conditions. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min and then mixed with 800 μl of ethanol. Then, 630 μl of the mixture was transferred to the QIAamp spin column and was centrifuged at 6000 × g for 1 min. Five-hundred microliters of washing buffer 1 (AW1 buffer) was added to the spin column and centrifuged at 6000 × g for 1 min. Then, 500 μl of washing buffer 2 (AW2 buffer) was added to the spin column and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 1 min. The DNA was eluted from the column by adding 40 μl of RNase- and DNase-free water. After centrifuging at 6000 × g for 1 min, the supernatant contained the DNA and was ready for use. In addition, the HBV DNA viral load was determined by real-time PCR which used the reagent of QUANTIPLEX™ HBV DNA Assay (Chiron Corporation, Emeryville, CA, USA) and the detection system of ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA). The HBV viral load of these seven samples ranged from an undetectable level to more than 5 × 107 copies/ml for the testing of our device.

3. Results

3.1. LAMP validation

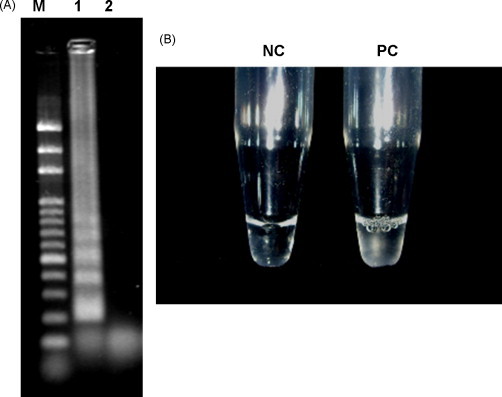

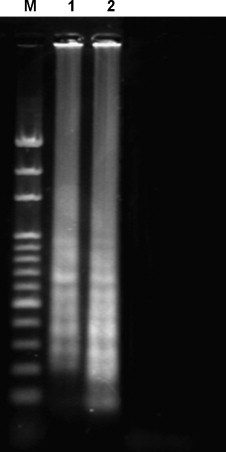

Following the principle of LAMP reaction, the amplified products elongated to a length of several kbp and when generated they showed complex cauliflower-like structures [9]. We demonstrated that the positive sample reveals many bands of different sizes after agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1A). With an increase of LAMP products, a large amount of by-product, magnesium pyrophosphate (Mg2P2O7), is produced and precipitated in the reaction mixture. The white precipitate of LAMP reaction by-product can be observed by naked eye (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

LAMP reaction validation. (A) Aliquots of 2.5 μl LAMP products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels (1× TBE) and then stained with SYBR Green I dye for verification by fluorescent imager. M: 100 bp DNA ladder; 1: HBV LAMP reaction (positive control); 2: negative control. (B) The white precipitate in positive control tube can be observed by naked eye (removed). PC: positive control; NC: negative control.

3.2. The integrated isothermal device

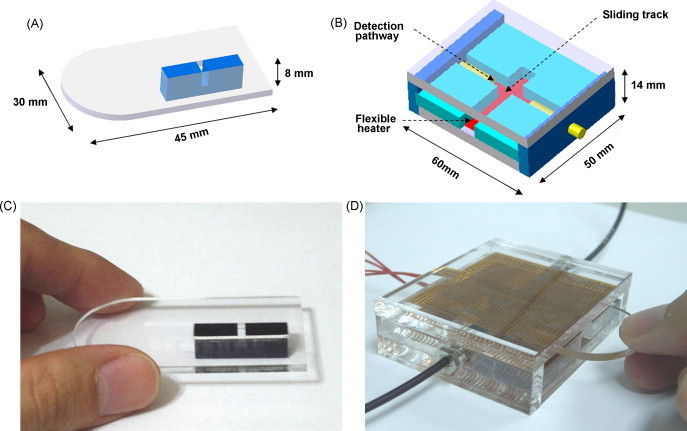

Other than the optimization of primers for the LAMP reaction, the reaction volume is a critical issue in the design of such a miniaturized device for amplification and detection. We decided to work with a total of 25 μl of LAMP reaction volume because of the practical limitations of turbidity detection. The prototype of our integrated isothermal device has two components: a disposable micro-reactor (Fig. 2A) and a temperature-regulated optical detection unit (base apparatus) (Fig. 2B). For the LAMP reaction, the disposable PMMA micro-reactor is filled with 25 μl reagent (Fig. 2C) and then sealed with gluey aluminum foil. It can be inserted into the base apparatus and the HBV LAMP reaction can be started under isothermal conditions. Simultaneously, we can detect the turbidity of the LAMP by-product in the base apparatus (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Illustrations and pictures of the integrated isothermal device. (A) The structure of the disposable micro-reactor. The disposable micro-reactor has a reaction chamber and 5-mm optical pathway. The reaction chamber is 5 mm-long, 2 mm-wide and 5 mm in height. (B) The structure of the base apparatus. The base apparatus is made with PMMA to create a detection pathway and sliding track. It has two slices of flexible heaters on the top and on the bottom sides. The light source fibers and the optical sensor are lined on the detection pathway and put close (about 10 mm) to each other. The reaction box is 60 mm-long, 50 mm-wide and 14 mm high. The detection pathway is 60 mm-long, 10 mm-wide, 5 mm-height and the sliding track is 35 mm-long, 6 mm-wide, 5 mm-height. (C) Picture of the disposable micro-reactor. This micro-reactor is just a home-made product. The disposable micro-reactor is constructed from two components of PMMA and glass slide cover. It has a reaction chamber and a 5-mm optical pathway without heaters or sensors. (D) Picture of the base apparatus. For the LAMP reaction, the reaction chamber is filled with 25-μl reagent and then sealed by gluey aluminum foil. The disposable micro-reactor component can be inserted into the base apparatus and the HBV LAMP reaction can be started under isothermal condition. This system can provide appropriate reaction conditions for HBV LAMP DNA amplification.

3.3. Performance of the integrated isothermal device

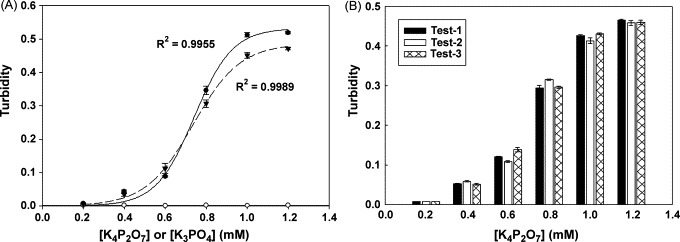

To evaluate the performance of the base apparatus for DNA amplification and detection, we have adapted a simulated chemical reaction to produce magnesium pyrophosphate. The simulated reaction utilizes potassium pyrophosphate and magnesium sulfate to synthesize magnesium pyrophosphate, as established in our previous study [20]. White precipitates can be observed when the concentration of pyrophosphate ions exceeds 0.4 mM. Fig. 3A shows the results of a 1 h end point turbidity measurement by using a spectrometer (R 2 = 0.9955) or our own system (R 2 = 0.9989) at 65 °C. Fig. 3B shows the reproducibility results of within run for turbidity detection in our device. It shows that the coefficient of variation (CV%) within run is very low (<6%). However, our system shows larger fluctuations between runs than does the spectrometer. This might be due to minor uncertainties in our fabricated devices, which will be able to control within acceptable limits with mass production of disposable chip.

Fig. 3.

To evaluate the efficiency and reproducibility of detecting the turbidity in the base apparatus by using chemical simulation reaction. (A) The by-product production of the LAMP reaction can be synthesized by chemical reaction. The reaction reagent contains Mg2+ ion and P2O74− (filled color) or PO43− (opened color) ion in reaction buffer. After 60 min reaction at 65 °C, turbidity can be detected by spectrometer (filled circle) at 533 nm wavelength or base apparatus (filled triangle). The mean values (triplicate tests) of turbidity closely fit the sigmoid curves. (B) We demonstrate the results of the within and between run to exhibit the reproducibility and stability of the base apparatus for turbidity detection. In our experiment, three sets of triplicate tests (inter- and intra-assay) under six different concentrations of pyrophosphate ion are performed. It shows that the coefficient of variation (CV%) of results is less than 6% of turbidity detection.

3.4. HBV LAMP analysis using integrated isothermal device

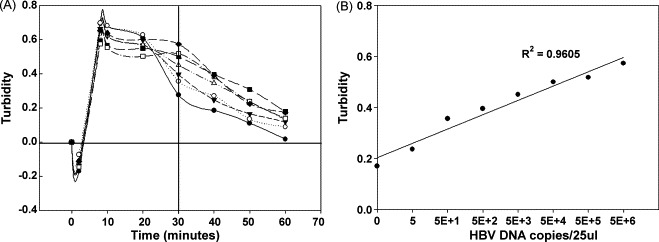

With a total of 25 μl of reagents and sample DNA in sealed reaction chamber, we can start the reaction under isothermal condition (65 °C) and monitor the intensity of scattering light by the optical unit. The real-time data on turbidity, decreases during the first 2 min, and then increases until reaching a plateau at 60 min. Fig. 4A shows the superimposed plots of turbidity data from different initial concentrations of DNA template. All of these samples show obvious changes in 30 min. From these results, it would be reasonable to take turbidity value of 30 min as a critical point for determining the end point of nucleic acid amplification. A linear relationship with a good correlation coefficient (R 2 = 0.9605) between measured values of turbidity and the initial concentration of DNA template is shown in Fig. 4B. The HBV LAMP reaction is also performed in the thermalcycler at 65 °C and then the amplified products are analyzed by electrophoretic analysis to confirm the consistency of the experimental results between our new system and the traditional system (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 4.

To verify the feasibility of detecting the turbidity in the integrated isothermal device by using the HBV LAMP reaction. (A) The serially 10-fold diluted HBV DNA plasmids, which contain the partial HBV polymerase gene, are used to verify the feasibility of detecting the turbidity in the part B component by using the HBV LAMP reaction ((♢) 5 × 106 copies/ml; (♦) 5 × 105 copies/ml; (□) 5 × 104 copies/ml; (■) 5 × 103 copies/ml; (▵) 5 × 102 copies/ml; (▾) 5 × 101 copies/ml; (○) 5 copies/ml; (●) negative control). (B) In 30 min, the turbidity of the HBV LAMP reaction obviously changes. The standard curve can be illustrated. The amount of initial template DNA is inversely correlated (R2 = 0.9605) with the turbidity determined by integrated isothermal device measurements.

Fig. 5.

To confirm the reality of detecting the turbidity by electrophoretic analysis. The HBV LAMP reaction is performed in the thermalcycler at 65 °C. Then, the amplified products can be analyzed by electrophoretic analysis to confirm the consistency of experimental results through comparisons between our new system and the traditional system. M: 100 bp DNA ladder marker; lane 1: the result of the HBV LAMP reaction is performed in the thermalcycler; lane 2: the result of HBV LAMP reaction is performed in the integrated isothermal device.

3.5. Quantitative analysis using clinical specimens

In our previous study, we demonstrated that our HBV LAMP reaction has great specificity and sensitivity (50 copies/25 μl) [20]. To confirm the results of the LAMP reaction for HBV DNA template amplification and detection in the integrated isothermal device, seven clinical serum specimens were obtained from patients with chronic hepatitis B at National Taiwan University Hospital. All of the serum specimens have been quantified by real-time PCR analysis as well. Table 1 shows the quantitative results of turbidity measurements when using the integrated isothermal device in the LAMP reagents containing the different amounts of DNA template from the clinical specimens. Following the results of the REVEAL-HBV study [2], the serum level of HBV DNA (≧10,000 copies/ml) is a strong risk predicator of hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis. Our quantitative results are good indicators for distinguishing the reported HBV DNA threshold level in serum in 1 h.

Table 1.

Quantitative analysis by using clinical specimens

| Specimen 1 | Specimen 2 | Specimen 3 | Specimen 4 | Specimen 5 | Specimen 6 | Specimen 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR (copies/ml) | Undetectable | <500 | 1,401.5 | 15,406 | 621,588 | 7,647,909 | >5E+7 |

| LAMP in integrated isothermal device (copies/ml) | 0/3 | 1/3 (1280) | 1/3 (1920) | 3/3 (19,480)a | 3/3 (845,400)a | 3/3 (6,943,632)a | 3/3 (93,423,405)a |

A series of seven serum specimens were obtained from patients at National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). The serum HBV viral DNA was extracted by using the QIAamp Viral DNA Mini Kit. In addition, the HBV DNA viral load was determined by real-time PCR. The HBV viral load of these seven samples ranged from an undetectable level to more than 5 × 107 copies/ml for the testing of our device. The frequency of positive results in triplicate test represents by fractional number. This pre-test shows the quantitative results of turbidity measurements when using the integrated isothermal device in the LAMP reagents containing the different amounts of DNA template from the clinical specimens. These results are good indicators for distinguishing the HBV DNA level in serum.

The mean value of triplicate tests.

4. Discussion

In our previous study [20], we have demonstrated that the HBV LAMP reaction can amplify specific DNA sequences in less than 1 h with high specificity and sensitivity (50 copies/25 μl). Unlike traditional PCR results, LAMP products consist of several inverted-repeat structures. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the positive LAMP reaction reveals many bands of different sizes. The sequences of LAMP products were confirmed by ABI 3100-avant DNA sequencer. Moreover, in a comparison of the LAMP reaction with PCR, the most significant advantage of the LAMP reaction is its ability to amplify specific DNA sequences under isothermal conditions (65 °C) without thermo-cycling. It thus has great potential for the development of an integrated isothermal device with disposable micro-reactor for low-cost applications.

Following the principle of LAMP reaction, both its yield of DNA and magnesium pyrophosphate precipitate are greater than PCR reaction [19]. In our system, an oven-like space has been designed and implemented to provide appropriate temperature conditions. An optical detection unit with a green LED light source is used to detect the LAMP reaction by turbidity derived from the magnesium pyrophosphate formation. In general, turbidity refers to the scattering of light by particles. Usually, turbidity is not measured directly, but it is estimated from the optical density (OD). It is assumed that the intensity of the input light is constant and that the samples have no absorbing constituents (DNA absorption peak: 260 nm) and that there are no changes in other loss mechanisms for the transmission of light, such as surface coatings, alignment, etc. Then the changes in detected light intensity can be ascribed to changes in total scattering. Thus, we interpret changes in detected light intensity as having resulted from changes in turbidity.

After the integrated isothermal device is constructed, the performance of the base apparatus should be confirmed. First, we check the efficiency of the heating and optical detection unit. We have adapted a simulated chemical reaction to mimic the by-product (magnesium pyrophosphate) production without using expensive polymerase and primers. Then, the results of the turbidity measurement from using a spectrometer are compared with the base apparatus. The reaction curves also have a similar trend between turbidity and initial amounts of potassium pyrophosphate. It shows that our system can provide appropriate reaction conditions for DNA amplification and detection. Second, we demonstrate that the results of within runs exhibit greater reproducibility of turbidity detection through the use of this base apparatus. This shows that our system has good stability. However, the results of between runs from our system show greater fluctuations than the results from the spectrometer, because of the disposable micro-reactor being a home-made product. In the future, we can use plastic molding for mass production to improve the quality and consistency of the micro-reactor and develop multi-channel micro-reactor type to achieve large-scale quantification test. The stability of light source and the precision of light-alignment are also important for the improvement of overall system performance.

After the performance of micro-reactor system is confirmed, HBV LAMP reactions can be transplanted into this system. The reaction curves decrease rapidly and achieve the lowest level of turbidity in 2 min. Then, the reaction curves increase quickly and achieve the highest level of turbidity in 8 min. We think that this phenomenon is related to the principle of Brownian motion [23]. When the reaction mixture is initially raised from room temperature to 65 °C, some microscopic clusters or particles may dissolve, causing an increase in the intensity of transmitted light. In 30 min, the turbidity of HBV LAMP reaction obviously changes. The standard curve shows that the numeric of the turbidity are highly correlated to the initial amounts of HBV template DNA (R 2 = 0.9605). After 30 min, gravity causes the numeric of turbidity to continually decrease because of the magnesium pyrophosphate precipitation. Therefore, the numeric of turbidity in 30 min could be a critical point for judging the performance of the HBV LAMP reaction. In addition, the HBV LAMP reaction is also performed in the thermalcycler. The amplified products can be analyzed by electrophoresis to confirm the consistency of the LAMP reaction between our device and thermalcycler. In Fig. 5, we show that the electrophoretic result of the HBV LAMP reaction is performed in the thermalcycler (lane 1) or in our device (lane 2). It seems that there are many small fragments (<200 bp) of HBV LAMP reaction as shown in lane 2. We presume that this phenomenon is related to the slow heat transfer in our device, which causes Bst DNA polymerase cannot elongate the LAMP product under stable condition, initially.

The REVEAL-HBV study indicates that serum level of HBV DNA (≧10,000 copies/ml) is a strong risk predicator of hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis [2]. Seven serum specimens with chronic hepatitis B were collected from National Taiwan University Hospital. These clinical specimens had triplicate tests by HBV LAMP reaction with this integrated isothermal device. The HBV viral load of these seven samples ranged from an undetectable level to more than 5 × 107 copies/ml for the testing of our device. The frequency of positive results in triplicate test represents by fractional number. In addition, our HBV LAMP reaction has good sensitivity (50 copies/25 μl). Even though the quantitative results from our device are higher than the data from real-time PCR, these results (Table 1) are valid to effectively distinguish the HBV DNA threshold level in the serum samples according to current protocol. Thus, using the integrated isothermal device provides great assistance for early diagnosing and monitoring the progress of chronic hepatitis B. However, there are several inhibitors from the blood samples that might potentially interfere with the amplification processes require further elucidations. In this study, the serum HBV viral DNA was extracted by using the QIAamp Viral DNA Mini Kit. The purified DNA is free of protein, nucleases, and other contaminants and inhibitors. In 2006, a study demonstrated that the LAMP assay does not require purified DNA for efficient DNA amplification [11]. These PCR inhibitors have little impact on the LAMP reactions even though there are inhibitors (e.g., heme) in blood could severely affect the amplification of DNA in PCR assays. As DNA polymerase have different susceptibilities to PCR inhibitors, they suspect that the Bacillus stearothermophilus (Bst) DNA polymerase used in the LAMP reactions is more resistant. In the future, the influence of various inhibitors, e.g., elevated levels of triglycerides, bilirubin, hemoglobin, and non-specific human DNA, will be addressed when we directly detect DNA from serum or heat-treated blood by LAMP. It would also be necessary for us to show that systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis have no impact on the method during large-scale clinical experiment. We will also try to improve the sensitivity and further reduce the reaction volume to 6 μl by using surface mode of optical detection [24], [25], [26].

In conclusion, we have successfully demonstrated the feasibility of the LAMP reaction for HBV DNA amplification and detection within 1 h in this novel integrated isothermal device. Using the LAMP reaction in the disposable micro-reactor component described here can amplify HBV DNA with high specificity and efficiency under isothermal conditions. The base apparatus component can also provide appropriate reaction conditions as well as a steady optical detection system for detecting turbidity derived from magnesium pyrophosphate formation without fluorescence labeling. Thus, using this integrated isothermal device greatly assists early diagnosing and monitoring the progress of chronic hepatitis B. It can improve the prognosis of patients and enormously save medical expenses. In the future, we hope to provide a multi-channel, portable, label-free, real-time monitoring medical device for rapid identification and quantification of pathogenic organisms and point-of-care applications.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from National Science and Technology Program (NSC 94-2614-B-002-001) for Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals of National Science Council. The authors thank the National Science Council for its assistance in facilitating international cooperation with the University of Washington, Seattle, USA.

Biographies

Szu-Yuan Lee was born in Taipei city, Taiwan. He received the BS and MS degree in medical technology from the School of Medical Technology, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, in 2001 and 2003, respectively. Currently, he is a PhD candidate of the Institute of Biomedical Engineering, College of Medicine and Engineering, National Taiwan University. He passed the Qualification Screening Examination for Professionals and Technologists and got the certificate of qualified medical technologist in 2001. In June 2006, he had a certificate of Technology Entrepreneurship and Management program from the College of Engineering, the College of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, and the College of Management, National Taiwan University. As a visiting international pre-doctoral scholar in July 2006, he joined an international project at the College of Electrical Engineering, University of Washington. In addition, he obtained the top 10 list of the 7th Industrial Bank of Taiwan (IBT) We-Win Entrepreneurship Competition Award and the top 5 list of the 8th TiC100 Talentrepreneur Innovation Competition in 2006. His research interests include cell biology, molecular biology, virology, biomedical micro-sensors and optical biochips.

Jhen-Gang Huang is a PhD candidate of Institute of Biomedical Engineering at National Taiwan University, Taiwan. He received his BS degree at Department of Medical Technology at National Yang Ming University, Taiwan on 1998; the MSc degree at Institute of Biomedical Engineering at National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan on 2001. His research interests include microanalytical systems in biomedical applications, miniature biosensors, electrochemical analysis and nanotechnology.

Tsung-Liang Chuang is a PhD student of Institute of Biomedical Engineering at National Taiwan University, Taiwan. He received his BS degree at Department of Medical Technology at Chung Shan Medical University, Taiwan on 1999; the MS degree at Institute of Biomedical Engineering at National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan on 2004, at which he designed a micro contact printing device for neuronal structure pattering. At 2003, he joined the 5th TIC100 Talentrepreneur Innovation Competition in Taiwan and obtained top 10 list at this competition. After graduated from NCKU, he worked as a research assistant at Institute of Biomedical Engineering, National Taiwan University from 2005–2007. Where he joined a scientific project cooperated with Congress of Agriculture, Taiwan and designed a portable system for fast screening of AIV (Avian Influenza virus). In 2006, he devoted part of research experiences in bio-analytical system design in the 7th Industrial Bank of Taiwan (IBT) We-Win Entrepreneurship Competition and the 8th TIC100 Talentrepreneur Innovation Competition in Taiwan, where he obtained top 10 list and top 5 list award, respectively. His research interests include, miniature biosensors, optical mechanical design in biosystems, neuronal cell structural patterning systems and nanotechnology.

Jin-Chuan Sheu received his BM from College of Medicine, National Taiwan University in 1973 and PhD in medical science from Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University in 1984. From 1986–1988, he attended to Cancer Center, University of Rochester and National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health, USA as a visiting fellow. He is currently a professor of Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University and majored in hepatogastroenterology. He was awarded NSC Outstanding Research Prize in 1988 and 1993. His research interests include molecular biology of liver disease especially carcinogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma and proteomics.

Yi-Kuang Chuang was born in Yunlin County, Taiwan. She obtained the BS in Medical Technology in 2001, the MS in clinical biochemistry in 2003 from the School of Medical Technology, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University. She also passed the Examination for Professionals and Technologists and got the certificate of qualified medical technologist in 2001. After completing her education, she attended to the Development Center for Biotechnology to be an assistant researcher in gene therapy program. It focused on gene and protein delivery systems, with emphasis on the design of vectors and the manufacturing processes. Currently, she is a medical technologist in the National Taiwan University Hospital.

Mark R. Holl (M’01) was born in Champaign, IL. He received the BS degree in mechanical engineering from Washington State University, Pullm an, in 1986, and the MS and PhD degrees in mechanical engineering from the University of Washington, Seattle, in 1990 and 1995, respectively. During his undergraduate student years, he was an Instrument Maker in the engineering machine shops at Washington State University. Prior to graduate research, he was with Boeing Commercial Aircraft, Renton, WA, and Everett, WA, for two years in Manufacturing, Research and Development in factory support and system functional test positions. As a postdoctoral fellow, he worked with professor P. Yager (Bioengineering, University of Washington) from 1995 to 1997 and was Principal Inventor of a laminate-based microfluidic technology and a Founding Member of a startup company born in part of this work, Micronics, Inc. He guided initial integrated system and microfluidic cassette development for Micronics through 1999. In 1999, he retuned to the University of Washington to further his interdisciplinary training while developing microfluidic device platforms for ongoing research needs. In 1999, he joined the Genomation Laboratory as a Research Engineer to develop microfluidic technologies for biomedical and genome science applications with Prof. D. Meldrum. Currently, he is a research assistant professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the University of Washington. His research interests include microfabrication technologies, micro and nanotechnology, microscale systems for biological applications, bioprocess automation, process sensors, and process characterization and control with an emphasis on biomedical, genomic, and proteomic science applications. Dr. Holl is a member of IAAAS, ASME, and an investigator in the NIH Center of Excellence in Genomic Sciences, the Microscale Life Sciences Center (MLSC) at the University of Washington. He joined Arizona State University (ASU) in January 2007, as Research Scientist of the Center for Ecogenomics in The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

Deirdre R. Meldrum (IEEE M’93-SM’00-F’04) was born in Loma Linda, California. She received the BS in civil engineering degree from the University of Washington, Seattle, WA in 1983, the MS in electrical engineering degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY, in 1985, and the PhD in electrical engineering degree from Stanford University, Stanford, CA, in 1993. As an Engineering Co-op student at the NASA Johnson Space Center in 1980 and 1981, she was an instructor for the astronauts on the Shuttle Mission Simulator. From 1985–1987, she was a Member of the Technical Staff at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and performed theoretical and experimental work in identification and control of large flexible space structures and robotics. She is currently a professor and director of the Genomation Laboratory in the Department of Electrical Engineering, Adjunct professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Her research interests include genome automation, microscale systems for biological applications, ecogenomics, robotics, and control systems. Dr. Meldrum is a member of AAAS, ACS, AWIS, HUGO, IEEE, Sigma Xi, and SWE. She was awarded an NIH Special Emphasis Research Career Award (SERCA) in 1993 to train in biology and genetics, bring her engineering expertise to the genome project, and develop automated laboratory instrumentation. In December 1996, she was the recipient of a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers for recognition of innovative research utilizing a broad set of interdisciplinary approaches to advance DNA sequencing technology. Since August 2001, she has directed an NIH Center of Excellence in Genomic Sciences called the Microscale Life Sciences Center (MLSC). In 2003, Dr. Meldrum became a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and in 2004, a fellow of IEEE. She is a Member of the National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research which advises the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), on genetics, genomic research, training and programs related to the human genome initiative, 2005–2008; Senior Editor for the IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2003-present; Steering Committee Representative for IEEE Robotics and Automation Society to the IEEE Transactions on NanoBioscience, September 2002-present; Member, EMBS Technical Committee on Biomedical Robotics October 2003-present; Representative for IEEE EMBS to the IEEE RAS-EMBS Advisory Committee, 2003-present; General and Program Co-Chair for the first IEEE RAS-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, Pisa, Italy, February 2006; Program Chair for the second IEEE Conference on Automation and Science and Engineering, Shanghai, China, October 2006. She participated in her first oceanographic research cruise aboard the R/V Thomas G. Thompson in September 2005, to develop ecogenomic sensors and participate in the first live broadcast of high definition (HD) video from the seafloor to land via satellite for the ResearchChannel. In August 2006, she made a dive to 2200 m below sea level on the submersible Alvin in the NE Pacific Ocean off the R/V Atlantis. She joined Arizona State University (ASU) in January 2007, as Dean of the Ira A. Fulton School of Engineering with 9 departments, 205 faculty, and 6,000 students. She is also Director of the Center for Ecogenomics in The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

Chun-Nan Lee received the BS degree from the Department of Medical Technology, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan in 1971, the MSPH degree from the Department of Pathobiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA in 1979, and the ScD degree from the Department of Cancer Biology, Harvard University, Boston, MA in 1995. She has been working as a teacher in the Department of Medical Technology (current name: Clinical Laboratory Sciences and Medical Biotechnology), National Taiwan University since 1980. She is currently a Professor and Chairperson of this Department. Her research interests include rapid laboratory diagnosis of viral infections, molecular epidemiology of gastrointestinal viral infections, and development of viral vaccines. Recently she has joined in a research group with mainly engineers to develop biomedical biosensors. Dr. Lee is a member of Taiwanese Society of Microbiology, American Society of Microbiology, and Asian Pacific Society of Medical Virology.

Chii-Wann Lin received his BS from Department of Electrical Engineering, National Cheng-Kung University in 1984. He obtained a MS degree from the Institute of Biomedical Engineering, National Yang-Ming University in 1986. After completing a two-year compulsory military service, he attended Case Western Reserve University where he received his PhD degree in Biomedical Engineering in January1993. After an eight month postdoctoral position as a Research Associate in the Neurology Department at Case Western Reserve University, he joined the Center for Biomedical Engineering, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University in Sept. 1993. Currently, he is a professor at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering. He also holds a joint appointment at the Department of Electrical Engineering, National Taiwan University. He is a member of IEEE EMBS, IFMBE and Chinese BMES. His research interests include biomedical micro-sensors, optical biochips, surface plasmon resonance, and nano-medicine.

References

- 1.McMahon B.J. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Semin. Liver Dis. 2005;25(Suppl. 1):3–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iloeje U.H., Yang H.I., Su J., Jen C.L., You S.L., Chen C.J. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678–686. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee C.Z., Huang G.T., Yang P.M., Sheu J.C., Lai M.Y., Chen D.S. Correlation of HBV DNA levels in serum and liver of chronic hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis. Liver. 2002;22:130–135. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2002.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S.J., Lee S.Y. Micro total analysis system (micro-TAS) in biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;64:289–299. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saiki R.K., Scharf S., Faloona F., Mullis K.B., Horn G.T., Erlich H.A., Arnheim N. Enzymatic amplification of beta-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science. 1985;230:1350–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.2999980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compton J. Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. Nature. 1991;350:91–92. doi: 10.1038/350091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker G.T., Fraiser M.S., Schram J.L., Little M.C., Nadeau J.G., Malinowski D.P. Strand displacement amplification—an isothermal, in vitro DNA amplification technique. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1691–1696. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lizardi P.M., Huang X., Zhu Z., Bray-Ward P., Thomas D.C., Ward D.C. Mutation detection and single-molecule counting using isothermal rolling-circle amplification. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:225–232. doi: 10.1038/898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., Hase T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E63. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagamine K., Hase T., Notomi T. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2002;16:223–229. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2002.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poon L.L., Wong B.W., Ma E.H., Chan K.H., Chow L.M., Abeyewickreme W., Tangpukdee N., Yuen K.Y., Guan Y., Looareesuwan S., Peiris J.S. Sensitive and inexpensive molecular test for falciparum malaria: detecting Plasmodium falciparum DNA directly from heat-treated blood by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clin. Chem. 2006;52:303–306. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.057901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwamoto T., Sonobe T., Hayashi K. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, M. avium, and M. intracellulare in sputum samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:2616–2622. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2616-2622.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong T.C., Mai Q.L., Cuong D.V., Parida M., Minekawa H., Notomi T., Hasebe F., Morita K. Development and evaluation of a novel loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:1956–1961. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1956-1961.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito M., Watanabe M., Nakagawa N., Ihara T., Okuno Y. Rapid detection and typing of influenza A and B by loop-mediated isothermal amplification: comparison with immunochromatography and virus isolation. J. Virol. Methods. 2006;135:272–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poon L.L., Leung C.S., Chan K.H., Lee J.H., Yuen K.Y., Guan Y., Peiris J.S. Detection of human influenza A viruses by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:427–430. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.427-430.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai M., Ninomiya A., Minekawa H., Notomi T., Ishizaki T., Tashiro M., Odagiri T. Development of H5-RT-LAMP (loop-mediated isothermal amplification) system for rapid diagnosis of H5 avian influenza virus infection. Vaccine. 2006;24:6679–6682. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwata S., Shibata Y., Kawada J., Hara S., Nishiyama Y., Morishima T., Ihira M., Yoshikawa T., Asano Y., Kimura H. Rapid detection of Epstein–Barr virus DNA by loop-mediated isothermal amplification method. J. Clin. Virol. 2006;37:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko H., Iida T., Aoki K., Ohno S., Suzutani T. Sensitive and rapid detection of herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus DNA by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:3290–3296. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3290-3296.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori Y., Nagamine K., Tomita N., Notomi T. Detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction by turbidity derived from magnesium pyrophosphate formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;289:150–154. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S.Y., Lee C.N., Mark H., Meldrum D.R., Lin C.W. Efficient, specific, compact hepatitis B diagnostic device: optical detection of the hepatitis B virus by isothermal amplification. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2007;127:598–605. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S.Y., Lee C.N., Holl M., Meldrum D.R., Lin C.W. Optimal hepatitis B virus primer sequence design for isothermal amplification. Biomed. Eng.: Appl. Basis Commun. 2007;19 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch A.L. Turbidity measurements of bacterial cultures in some available commercial instruments. Anal. Biochem. 1970;38:252–259. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanagida T., Ueda M., Murata T., Esaki S., Ishii Y. Brownian motion, fluctuation and life. Biosystems. 2007;88:228–242. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin C.W., Chen K.P., Su M.C., Hsiao T.C., Lee S.S., Lin S.M., Shi X.J., Lee C.K. Admittance loci design method for multilayer surface plasmon resonance devices. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2006;117:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin C.W., Chen K.P., Lin S.M., Lee C.K. Design and Fabrication of an Alternating Dielectric Multi-layer device for Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2006;113:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J.G., Lee C.L., Lin H.M., Chuang T.L., Wang W.S., Juang R.H., Wang C.H., Lee C.K., Lin S.M., Lin C.W. A miniaturized germanium-doped silicon dioxide-based surface plasmon resonance waveguide sensor for immunoassay detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006;22:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]