Abstract

Frontal horn cysts (FHCs) are elliptical, smooth, thin-walled cysts adjacent to the tip of the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles. Among 3545 terms or near term healthy babies who underwent cranial ultrasound examination in our hospital over a 2-year 5-month period, 18 were found to have FHCs (17 typical and one atypical; seven bilateral and 11 unilateral, of which seven were on the left and four on the right). The female to male ratio was 2:1. The incidence of FHCs in normal term babies was thus 0.5%. Six children had resolution of the cyst within 1 month, and 6 more had resolution on repeat scan from 2 to 11 months of age. Four children did not have subsequent ultrasonography to document resolution, but they had normal growth and development. Two were lost to follow up. The infant with an atypical FHC had an enlarged left frontal horn cyst with a midline shift on follow up, but he had normal development. Our study suggests that FHC may be a normal physiologic variant or a benign pathologic condition that can be expected to resolve spontaneously within a few months. It is reasonable to follow typical FHC by cranial ultrasound examinations at 1 or 2 and 6 months of age. In the case of an atypical cyst, more frequent follow up and further image studies like CT or MRI are necessary.

Keywords: Frontal horn cysts, Subependymal cysts, Periventricular cysts, Intracranial cysts, Cranial ultrasound examination

1. Introduction

Frontal horn cysts (FHCs) are uncommon cranial ultrasound findings about which only a few reports have been published [1]. FHCs were previously called periventricular cavitation [2], frontal periventricular cysts [3], or transient bifrontal solitary periventricular cysts [4]. Sometimes they are classified together with cysts in the caudothalamic notch (subependymal cysts) as subependymal pseudocysts [5], [6], [7]. They may be confused with subependymal cysts or periventricular leukomalacia, but their prevalence, location, sonographic appearance, etiology, and outcome are different [8], [9], [10], [11].

Most reported FHCs have occurred in premature infants, but the series have been small [1], [2], [3], [5], [6], [7]. The only report of term infants with FHC included three cases [4]. The largest reported group is 21 subjects reported by Pal et al. [1]. They described the distinctive morphology (elliptical, smooth, thin walled, ranging from 3 to 20 mm), and position (adjacent to the tip of the anterior horns) and introduced the current name of FHC. In most previously reported cases, infants had other pathologic conditions, such as prematurity, respiratory distress syndrome, or infection, and some had neurologic sequelae such as spastic diplegia or mental retardation.

In this study, we reviewed our experience with FHCs in healthy full-term neonates.

2. Methods

From July 2001 to November 2003, 3545 normal term or near-term newborns underwent cranial ultrasound examination after their parents gave consent for the procedure. The infants had all been examined after birth by both an obstetrician and a pediatrician and were deemed to be healthy. Eighteen of these babies were found to have FHCs and were included in this study. Their perinatal history, physical examination, ultrasound findings, and outcome were reviewed.

The initial cranial ultrasound scans were all performed in the first 3 days after delivery by using a Toshiba SSD260A real-time scanner with a 7 MHz transducer. An Acuson Aspen real-time scanner with multi-frequency high resolution transducers (5–7 MHz) was used for follow up studies. Multiple coronal, sagittal, and parasagittal views were obtained from the anterior fontanel in each examination. All initial and follow up cranial ultrasound examinations were performed by pediatric neurologists.

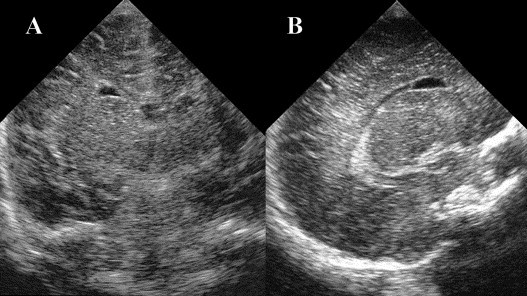

All 18 infants had cysts adjacent to the lateral tip of the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle. Cysts with the distinctive elliptical, smooth, thin-walled morphology of FHCs were considered typical (Fig. 1 A,B). The term atypical was applied if the cyst did not totally fulfill the typical morphology but occupied the same location as typical FHCs.

Fig. 1.

Coronal (A) and parasagittal (B) cranial ultrasonographic views showing the typical elliptical, smooth, thin walled appearance of a frontal horn cyst adjacent to the tip of the anterior horns.

A second cranial ultrasound examination at 1 month of age was recommended for all babies diagnosed with an FHC, with serial follow up to continue at intervals of 2 months until the cysts disappeared. However, because of outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003, some parents opted not to take their babies to the hospital. The Denver Development Scales were used to evaluate development of the infants who did not have follow up scans.

3. Results

The incidence of FHC in normal newborns in our series was 0.5% (18/3545). The incidence of subependymal cyst was 11.90% and choroid plexus cyst 1.21%. The characteristics and clinical and ultrasound findings of the 18 subjects are listed in Table 1 . All FHCs were found in the first 3 days after birth by ultrasound examination. No other sonographic abnormalities were seen. The antenatal history and delivery were unremarkable in all 18. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities except for subject 3, who had bilateral simian fissures, and subject 13, who had a small anal polyp. All infants were full term or near full term. The gestational age ranged from 36 to 41 weeks, the head circumference from 30.5 to 35.5 cm, and the birth weight from 1986 to 3618 g. The female to male ratio was 2:1 (12/6). The FHC was bilateral in seven and unilateral in 11 (7 left, 4 right). Only one baby had an atypical FHC.

Table 1.

Characteristics and ultrasound findings in 18 normal healthy infants with frontal horn cysts found after birth

| Case | GA | Sex | G | P | BW (g) | Delivery | HC (cm) | Location | Type | Follow up age (mo) | Other clinical findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | F | 2 | 1 | 2352 | NVD | 30.5 | Bilateral | T | 1, 3 (D) | |

| 2 | 38 | M | 1 | 1 | 2832 | CS | 33 | Right | T | 2 (D) | |

| 3 | 38 | M | 1 | 1 | 2828 | CS | 34 | Right | T | 1, 6 (D) | Bilateral simian fissures |

| 4 | 36 | M | 4 | 2 | 2328 | CS | 32.5 | Bilateral | T | ND | |

| 5 | 39 | F | 3 | 2 | 3618 | NVD | 34 | Bilateral | T | 1, ND | |

| 6 | 38 | F | 4 | 2 | 2830 | CS | 35 | Bilateral | T | 1 (D) | |

| 7 | 39 | F | 3 | 1 | 3228 | CS | 34.5 | Right | T | 1 (D) | |

| 8 | 36 | F | 1 | 1 | 1986 | NVD | 31 | Left | T | 1, lost to follow up | |

| 9 | 38 | F | 3 | 3 | 3426 | CS | 35 | Bilateral | T | 1, 4 (D) | |

| 10 | 40 | F | 3 | 2 | 2842 | NVD | 32.5 | Left | T | ND | |

| 11 | 40 | M | 1 | 1 | 2938 | NVD | 32.5 | Left | T | 1 (D) | |

| 12 | 41 | F | 1 | 1 | 2824 | NVD | 32 | Right | T | 1, 11 (D) | |

| 13 | 38 | F | 2 | 1 | 3010 | CS | 34 | Bilateral | T | Lost to follow up | Small anal polyp |

| 14 | 39 | F | 2 | 2 | 3530 | NVD | 34 | Bilateral | T | 1 (D) | |

| 15 | 39 | M | 2 | 2 | 3488 | NVD | 35.5 | Left | T | 4, 6 (D) | |

| 16 | 38 | F | 3 | 1 | 2868 | NVD | 32.5 | Left | T | 1 (D) | |

| 17 | 39 | M | 3 | 2 | 3540 | NVD | 34 | Left | AT | 2, 4, ND | |

| 18 | 39 | F | 4 | 3 | 3400 | NVD | 33 | Left | T | 1 (D) |

GA, gestational age in weeks; G, gravidity; P, parity; BW, birth weight in grams; HC, head circumference; F, female; M, male; NVD, normal vaginal delivery; CS, Cesarean section; D, age of disappearance of the frontal horn cyst; T, typical; AT, atypical; ND, normal Denver development score.

Among the 17 infants with typical FHCs, 12 infants had repeat ultrasound at 1 month of age. Of these 12, the cyst had disappeared in six (50%) by 1 month, one patient was later lost to follow up, and the remaining five had repeat scans that showed disappearance of the cyst by 3–11 months of age. One infant had only one follow up scan at 2 months, which showed resolution of the cyst. Among the other four infants with typical FHC, one was lost to follow up, one had a persistent cyst at 1 month and no further scan but was subsequently normal on Denver Developmental screening, and the other two had normal development but no follow up scans.

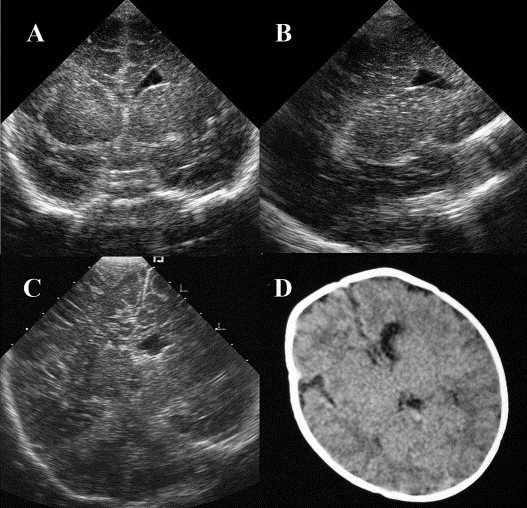

Infant 17 had an atypical FHC in that the cyst did not have the typical elliptical shape (Fig. 2 A,B). It enlarged and exerted a mass effect, compressing the contralateral hemisphere; a midline shift was seen on the follow-up examination at two months. This finding was confirmed by computed tomography (Fig. 2C,D). However, when the child was 4-months-old, the cyst had not enlarged and there was no further mass effect. The infant was developmentally normal.

Fig. 2.

Atypical frontal horn cyst in subject 17. (A,B) The initial coronal and parasagittal views show the cyst adjacent to the left frontal horn but without the typical elliptical shape. (C) A follow-up coronal view shows a midline shift to the right. (D) Follow-up cranial computed tomography shows the cyst adjacent to the frontal horn of the left lateral ventricle with the midline mildly deviated to the right.

4. Discussion

In our 18 cases, almost all of the FHCs were typical in both location and shape, and they were all identified on the first cranial ultrasound examination done soon after birth. Their typical elliptical shape and location can differentiate them from subependymal cysts. They were apposed to the lateral wall of the frontal horn and separated from it by a thin wall. They are not at the most vulnerable germinal matrix where subependymal cysts happen. No concomitant cranial ultrasound abnormalities, especially subependymal cysts, were found on initial examination. The infants' perinatal histories were uneventful. Their similar elliptical cyst shape, fixed location, absence of other concomitant cysts and innocuous clinical course with spontaneous resolution in most cases suggest that FHC should not be classified together with subependymal or other cysts.

The etiology of FHC may differ from that of other cysts, although it is currently not known with certainty. Several hypotheses have been proposed, including antepartum hemorrhage, grade IV parenchymal hemorrhage, infarction, ischemia, infection, a small area of periventricular leukomalacia, or degeneration of the periventricular germinal matrix [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [12]. Rosenfeld et al. suggested that FHC occurred secondary to a coarctation of the lateral ventricle rather than as a sequela of hemorrhage or ischemia [7]. Pal et al. thought that FHC could be explained by initial secretory activity of the ependymal lining, allowing the cyst to increase in size as the surrounding brain grew. In this view, loss of ependymal cells or of their secretory function results in cyst shrinkage. This hypothesis has histological support from an autopsy case [1]. No definite etiology could be identified in our infants.

The major published reports of FHC are listed in Table 2 . The incidence in premature and in term babies is reportedly similar, ranging from 0.48 to 0.91%. This suggests that FHC has little to do with prematurity and its associated stress. The benign outcome may be due to no important tract pass through the frontal horn area. Given these reports and, in our series, the similar elliptical, smooth, thin-walled appearance, their fixed location and similar incidence between prematurity and term baby, the absence of destruction of the surrounding brain tissue and absence of concomitant cranial ultrasound abnormalities, the normal perinatal history and subsequent development, we suspect that typical FHC may be a normal physiologic variant or a benign pathologic condition.

Table 2.

Published series of frontal horn cysts

| Keller et al. (1987) | Zorzi et al. (1989) | Sudakoff et al. (1991) | Rademaker et al. (1993) | Pal et al. (2001) | Our series | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 11 | 8 of 19a | 7 | 8 | 21 | 18 |

| Gestational age (wks) | 9 subjects <35 | 6 subjects <37 | 29–36 | 5 subjects <33 | 20 subjects <35 | 36–41 |

| 2 subjects=40 | 36,38,39 weeks | 1 subjects=42 | ||||

| Incidence | Rare | 0.91% (8/879) | 0.48% (7/1453) | 0.87% (8/920) | 0.72% (21/2914) | 0.50% (18/3545) |

| Unilateral FHC | 4/11 (36%) 4 left | 2/8 (0.25%) | 5/7 (71%) 3 left, 2 right | 4/8 (50%) 2 left, 2 right | 12/21 (57%) 9 left, 3 right | 11/18 (61%) 7 left, 4 right |

| Bilateral FHC | 7/11 (64%) | 6/8 (0.75%) | 2/7 (29%) | 4/8 (50%) | 9/21 (43%) | 7/18 (39%) |

| Male/female | 4/4 | 5/3 | 9/12 | 6/12 | ||

| Regression age | 1 at 4 and, 2 at 6 months old | Median corrected age 2 months (range 34 weeks to 4.5 months) | 50% at 1 months, most before 6 months | |||

| Outcome | 1 Developmental delay with seizure, 1 death | 1 Death, 1 quadraparesis, 1 severe motor delay | 1 Hypertonia at 1 year of age | 2 Died of complications, others normal | 2 Mild diplegia, 1 spastic diplegia, others normal | Normal |

Eight of 19 subependymal pseudocysts were diagnosed as frontal horn cysts.

Serial cranial ultrasound examinations are useful for follow up. With half the cysts disappearing by 1 month in those scanned at that age, plus the subsequent resolution in most of the rest by age 6 months, it seems reasonable to repeat the scan at 1 or 2 months of age. If the cyst persists in that scan, another examination at six months is indicated, with subsequent scans if needed.

When the FHC is atypical, it should be distinguished from periventricular leukomalacia or porencephaly [13], although these are rarely seen in the lateral aspect of the frontal horn. And according to the Rademaker KJ et al., the frontal horn cyst is located at the external angle below the level of the lateral ventricles, whereas cysts occurring in periventricular leukomalacia extend above this level [6]. The only atypical cyst in our series did enlarge somewhat and had an initial mass effect, but the child's subsequent course was uneventful. More frequent follow up for an atypical FHC may be necessary, as the prognosis is not as clear as for typical cysts. Further, image studies like MRI or CT should be considered. While it may be a variant FHC, it may also belong to a different subset of intracranial cysts with a different prognosis.

Our study was limited by the relatively small number of cases and short-term follow up. Larger longitudinal investigations are needed to clarify the course of typical FHC, especially to confirm the apparently good prognosis. Autopsy studies may help to elucidate the etiology and pathophysiology of the disorder.

References

- 1.Pal B.R., Preston P.R., Morgan M.E., Rushton D.I., Durbin G.M. Frontal horn thin walled cysts in preterm neonates are benign. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;85(3):F187–F193. doi: 10.1136/fn.85.3.F187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller M.S., DiPietro M.A., Teele R.L., White S.J., Chawla H.S., Curtis-Cohen M. Periventricular cavitations in the first week of life. Am J Neuroradiol. 1987;8(2):291–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudakoff G.S., Mitchell D.G., Stanley C., Graziani L.J. Frontal periventricular cysts on the first day of life: a one-year clinical follow-up and its significance. J Ultrasound Med. 1991;10(1):25–30. doi: 10.7863/jum.1991.10.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thun-Hohenstein L., Forster I., Kunzle C., Martin E., Boltshauser E. Transient bifrontal solitary periventricular cysts in term neonates. Neuroradiology. 1994;36(3):241–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00588143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zorzi C., Angonese I. Subependymal pseudocysts in the neonate. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;148(5):462–464. doi: 10.1007/BF00595915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rademaker K.J., De Vries L.S., Barth P.G. Subependymal pseudocysts: ultrasound diagnosis and findings at follow-up. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82(4):394–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld D.L., Schonfeld S.M., Underberg-Davis S. Coarctation of the lateral ventricles: an alternative explanation for subependymal pseudocysts. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27(12):895–897. doi: 10.1007/s002470050265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen E.Y., Huang F.Y. Subependymal cysts in normal neonates. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60(11):1072–1074. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.11.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larcos G., Gruenewald S.M., Lui K. Neonatal subependymal cysts detected by sonography: prevalence, sonographic findings, and clinical significance. Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(4):953–956. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.4.8141023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shackelford G.D., Fulling K.H., Glasier C.M. Cysts of the subependymal germinal matrix: sonographic demonstration with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1983;149(1):117–121. doi: 10.1148/radiology.149.1.6310678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takashima S., Iida K., Deguchi K. Periventricular leukomalacia, glial development and myelination. Early Hum Dev. 1995;43(2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(95)01675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larroche J.C. Sub-ependymal pseudo-cysts in the newborn. Biol Neonate. 1972;21(3):170–183. doi: 10.1159/000240506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eller K.M., Kuller J.A. Fetal porencephaly: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and prognosis. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50(9):684–687. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199509000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]