Dear Editor,

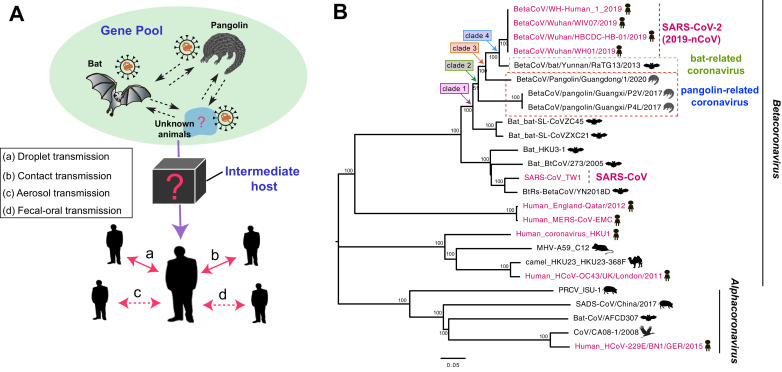

Recent study reported in this journal that the threats of continuous evolution and dissemination of 2019 novel coronaviruses.1 Since its emergence in December 2019, a “seventh” member of the family of human coronavirus named “SARS-CoV-2” was responsible for an outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China.2 As of March 7, 2020, China had reported more than 80,815 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2, with 3,073 fatalities and counting (http://www.nhc.gov.cn). Strikingly, SARS-CoV-2 had been transmitted rapidly in more than 90 countries to date (https://www.who.int), including Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Oceania, posing serious concerns about its pandemic potential. Despite of droplet and contact transmissions of SARS-CoV-2, recent studies demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 might be transmitted via aerosol and fecal–oral routes 3 (Fig. 1 ), which needs to be paid attention in particular.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenic overview and putative model of transmission of SARS-CoV-2. (A) Potential routes of cross-species transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The dashed line indicates potential transmission routes. Abbreviation of SARS-CoV-2 indicates 2019 novel coronaviruses. (B) The phylogenetic relationship among SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses in bats, birds, mice, camels, swine, pangolins, and humans. Red color indicates the human-origin coronaviruses. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site (subs/site).

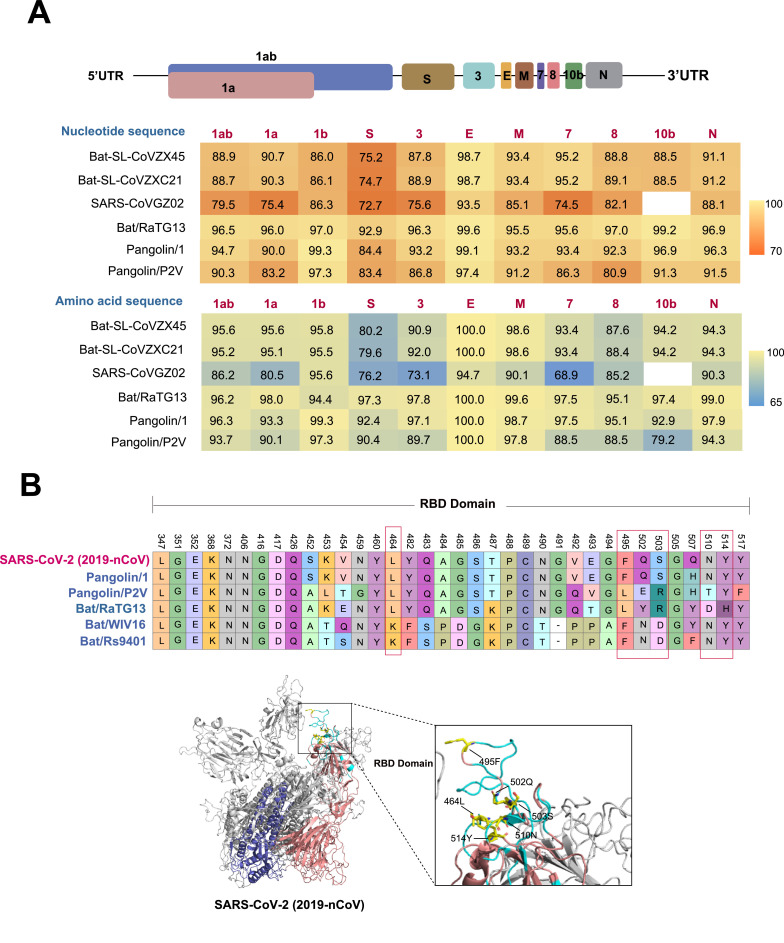

The close phylogenetic relationship to bat-origin coronaviruses provided evidence for a bat origin of SARS-CoV-2.4 Bats provided a rich “gene pool” for interspecies exchange of genetic fragments of coronaviruses, which were established as mixing vessels of different coronaviruses.5 Although humans and bats live in different environments, some wildlife species were susceptible to the novel coronaviruses in nature, highlighting that the need of tracing its origin of SARS-CoV-2 in wild animals. Previously, researchers had demonstrated that coronaviruses had been detected in pangolins.6 Here, we explored the phylogenic relationship of the human SARS-CoV-2 together with pangolin- and bat-origin coronaviruses. The similarity analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and the animal-origin coronaviruses demonstrated that recombination events were likely to occur in bat- and pangolin-origin coronaviruses (Supplementary Figure S1). A Blast search of the compete genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 suggested that the closely related coronaviruses were the BetaCoV/bat/Yunnan/RaTG13/2013 (bat/RaTG13) and BetaCoV/Pangolin/Guangdong/1/2020 (Pangolin/1), with ∼96% and ∼ 90.5% overall genome sequences identity, respectively. In the 1ab, S, E, M, and N genes, the bat/RaTG13 coronavirus exhibited 96.2%, 97.3%, 100%, 99.6%, and 99.0% amino acid identical to that of SAR-CoV-2, respectively, while the pangolin/1 coronavirus showed the 96.3%, 92.4%, 100%, 98.7%, and 97.9% amino acid identical to that of SARS-CoV-2, respectively (Fig. 2 ). However, it was notably that 1b gene sequence identity of pangolin/1 coronavirus was greater that bat-origin RaTG13 coronavirus, with the highest being 99.3%.

Fig. 2.

The genomic characterization and specific amino acids variants among the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2, bat- and pangolin-origin coronaviruses. (A) The schematic diagram of the genome organization and sequence identities for SARS-CoV-2 compared with SARS-CoV GZ02 (accession number AY390556), bat SARS-like coronavirus bat-SL-CoVZC45 (accession number MG772933), bat-SL-CoVZXC21 (accession number MG772934), BetaCoV/bat/Yunnan/RaTG13/2013 (bat/RaTG13) (accession number EPI_ISL_40,131), BetaCoV/Pangolin/Guangdong/1/2020 (Pangolin/1) (accession number EPI_ISL_410,721), and BetaCoV/Pangolin/Guangxi/P2V/2017 (Pangolin/P2V) (accession number EPI_ISL_410,542). (B) Amino acid substitutions of SARS-CoV-2 against bat- and pangolin-origin coronaviruses. An amino acid substitution of spike (S) protein is defined as an absolutely conserved site in the bat- and pangolin-origin coronaviruses but different from that of SARS-CoV-2. Structural analysis of S protein of SARS-CoV-2 was modelled using the Swiss-Model program (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) with that of the S protein of SARS-CoV structure (Protein Data Bank ID 2DD8) as a template. The red and blue regions indicate the spike protein 1 and spike protein 2, respectively. The wathet blue region of SARS-CoV-2 indicates the receptor binding region. The correspondencing amino acids to the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 were mapped using MacPymol (http://www.pymol.org/).

The spike (S) protein mediates receptor binding and membrane fusion.7 The amino acids of the spike 2 protein of pangolin-origin coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2 were more conserved than that of the spike 1 protein, and only a few minor deletions of amino acids of S protein were found in pangolin-origin coronavirus compared with the SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Figure S4). Interestingly, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 was more similar to that of the bat/RaTG13 strain and Pangolin/1 coronavirus. Although the S amino acid identities of pangolin-origin coronavirus exhibited lower amino acid identities with bat/RaTG13, it was noteworthy that six amino acids associated with the receptor binding preference of human receptor angiotensin converting enzyme II—464 L, 495F, 502Q, 503S, 510 N, and 514Y (SARS-CoV-2 numbering)—in the pangolin/1 coronavirus were the same as that of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2), but were distinct from that of the bat-origin coronaviruses. Besides, the PRRA-motif insertion was occurred in the S1/S2 junction of SARS-CoV-2; however, the PRRA-motif insertion in the pangolin- and bat-origin coronaviruses was missing (Supplementary Figure S4), suggesting that the convergent cross-species evolution of SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses.

The phylogenic tree of full-genome of SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses could be classified into four clades, including clade 1, clade 2, clade 3, and clade 4 (Fig. 1). The two bat-origin SARS-like strains (bat-SL-CoVZC45 and bat-SL-CoVZXC21) formed clade 1, and pangolin-derived Pangolin/1, BetaCoV/ Pangolin/Guangxi/P2V/2017 (Pangolin/P2V), and BetaCoV/Pangolin/Guangxi/P4L/2020 (Pangolin/P4L) coronaviruses formed newly independent clade 2 and clade 3, which were notable for the long branch separating the bat/RaTG13 strain and SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1). Of note, we found that the full genome and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase genome of Pangolin/1 coronavirus were genetically closely related to the bat/RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 strains (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figure S3). However, in the phylogenic tree of S gene, the Pangolin/P2V and Pangolin/P4L coronaviruses were more closely related to that of the bat/RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 strains (Supplementary Figure S2), indicative of the continuous evolution and genetic recombination of pangolin- and bat-derived coronaviruses. There was clearly a genetic gap between SARS-CoV-2 and the nearest bat- and pangolin-origin coronaviruses, and the phylogenic relationship of pangolin-origin coronaviruses were far from that of bat/RaTG13 (Fig. 1). Given the use of pangolins use in traditional medicine and for food, what kind of role do the pangolins play in the cross-species evolution and transmission of the novel coronavirus? Further details needed to be sought in the future.

Frequent human-animal interface had been recognized the major cause for viral cross-species transmission. It is speculated that the coronaviruses circulating in pangolin, bat, and other animal species are likely perceived to be a “gene pool” for the generation of new recombinants (Fig. 1). During the long-time of co-existence of coronaviruses and their hosts, different viruses recombine with each other in multiple animal hosts to generate new recombinants, with some of them adapting to the new hosts such as humans. However, what animal species are the intermediate hosts in the transmission cascade of SARS-CoV-2. In response to such pressing question, further surveillance in natural environment of China and the rest of countries needed to be sought to understand the emergence and potential transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank the authors of the human 2019 coronavirus from GISAID EpiFlu™ Database. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31941014, 31830097, 31672586), the Key Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2019B020218004), Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-41-G16), Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2018, Wenbao Qi), and Young Scholars of Yangtze River Scholar Professor Program (2019, Wenbao Qi).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.025.

Contributor Information

Ming Liao, Email: mliao@scau.edu.cn.

Wenbao Qi, Email: qiwenbao@scau.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Zhang J., Ma K., Li H., Liao M., Qi W. The continuous evolution and dissemination of 2019 novel human coronavirus. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorbalenya A.E. Severe acute respiratory-related coronavirus—The species and its viruses, a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.07.937862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.06.20020974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou P., Yang X., Wang X., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu B., Zeng L., Yang X., Ge X., Zhang W., Li B. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. Plos Pathog. 2017;13(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu P., Chen W., Chen J. Viral metagenomics revealed sendai virus and coronavirus infection of Malayan Pangolins (Manis javanica) Viruses. 2019;11(11) doi: 10.3390/v11110979. pii: E979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu G., Wang Q., Gao G.F. Bat-to-human: spike features determining ‘host jump’ of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.