Abstract

This study used the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to examine taxpayers' acceptance of the Internet tax-filing system. Based on data collected from 141 experienced taxpayers in Taiwan, the acceptance and the impact of quality antecedents on taxpayers' perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) of the system were assessed and evaluated. The results indicated that the model of Internet tax-filing system was accepted with a reasonable goodness-of-fit. Three important findings include the following items. First, TAM proves to be a valid model to explain the taxpayers' acceptance of the Internet tax-filers' system. Meanwhile, PU has created more impact than PEOU on taxpayers' intention to use the system. Second, PU is positively influenced by such factors as information system quality (ISQ), information quality (IQ), as well as perceived credibility (PC). Third, IQ has a positive impact on PEOU. Based on the research findings, implications and limitations are then discussed for future possible research.

Keywords: Technology acceptance model (TAM), DeLone and McLean model (D&M model), Internet tax-filing acceptance

1. Introduction

In Taiwan, there are three major tax-filing methods: manual filing, two-dimension (2D) bar code filing, and Internet filing. Since 1998, the Taiwan government has moved aggressively to promote Internet tax filings under the e-government initiative, the goals of which are a paperless environment, an efficient process, and the public's convenience in contacting government agencies.1 The tax authority in Taiwan, the National Tax Administration (NTA), promoted the system by providing incentives, such as faster tax refunds and online credit card payment, which results in an increasing number of Internet tax filers (see Table 1 ). With regard to the aforementioned three methods, public satisfaction is greatest with the 2D bar code filing, and the manual filing method is the least satisfactory.2 Despite all the efforts of NTA's promotion and the low satisfaction, traditional manual filing remains the most widespread method. Though 2D bar code is classified as an electronic tax-filing method, it still requires taxpayers to print their return in paper form and mail it to the government agent. Therefore, this study focuses on the Internet tax-filing method, the only method that would eventually achieve one of the e-government's goals to be paperless, and examines the critical factors that influence the acceptance of the Internet tax-filing system.

Table 1.

The number of income taxpayers of three tax-filing methods

| Year | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual filing | 3,965,277 (78.89%) | 3,282,077 (71.24%) | 2,688,716 (57.66%) |

| 2D bar code filing | 1,023,429 (20.36%) | 976,557 (21.20%) | 1,218,899 (26.14%) |

| Internet filing | 37,621 (0.75%) | 348,156 (7.56%) | 755,508 (16.20%) |

Source: National Tax Authority, Taiwan.1

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is among the most influential and discussed theories in explaining and predicting the individual's acceptance of information technology. Several past studies have examined the relationship of perceived ease of use (PEOU), perceived usefulness (PU), attitudes, intention, and the usage of information technologies. Lee et al.3 summarized the information systems examined by TAM in 101 articles published by leading IS journals and conferences from 1986 to 2003 into four different classes: communication system (20%), general purpose system (28%), office system (27%), and specialized business system (25%). Among this research, little was done in the e-government area. However, applying TAM to the e-government system can lead to a better understanding not only of public acceptance of the Internet tax-filing system but also of the possible differences between the e-government and other types of Internet applications.

Since the Internet tax-filing system is still new to most of the public, the earlier adopters may share the same personal characteristics. As a result, this paper focuses only on the quality factors that influence the acceptance of Internet tax-filing software. Information system quality (ISQ) and information quality (IQ) were often used in the evaluation of system usability.4., 5., 6. Many researchers have validated the relationships between these two quality factors and system use.7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13. Additionally, perceived credibility (PC) was indicated as an influential factor affecting the electronic tax-filing system.14 Altogether, the authors proposed a TAM-like research framework with the ISQ, IQ, and PC of the Internet tax-filing system that affect the taxpayers' PU and PEOU, and additionally the attitude and the intention to utilize the system.

2. Literature review

The Internet tax-filing system provides online tax service to taxpayers and is one kind of government to customer (G2C) electronic service. Furthermore, G2C e-service is one part of the e-government domain. Consequently, the definitions and characteristics of e-government and the Internet tax filing are reviewed in this section. In addition, the related research about TAM and DeLone and McLean's taxonomy, which provides the basis for this research framework, is also reviewed in this section.

2.1. E-government

E-government can be defined as the use of information technology in general, and the utilization of the Internet in particular, to provide citizens and organizations with more convenient access to government's information and services. On the other hand, government can deliver public services to citizens and organizations electronically and even facilitate them to these aforementioned services through IT.15., 16. From a technical perspective, e-government can be seen as a new technology used by government to help simplify and automate transactions among governments and constituents, businesses, or other governments.17 From an economics perspective, e-government defines a new market and a new type of government—a powerful channel to distribute public services interactively.18 As to the context of the e-government, an integral part of the “information society” and “digital economy” visions were formed.

Under the e-government concept, governments usually find themselves confronted with a broad range of political themes arising from the need to re-establish their vision and role19 and re-structure their services around the concept of “citizen as customer.”20 Just like business to customer (B2C) in e-commerce, a well-established G2C e-government can provide citizens with all the information they need on the Web. Citizens can ask questions and receive corresponding answers, pay taxes and bills, receive payments, view documents, and access other services that are available 24 hours a day through the Internet. In the information systems domain, a variety of users' behavior effects have been theoretically discussed and empirically demonstrated in the previous research. However, few studies about G2C e-services are done.

Because of the challenges from the inner and outer environmental changes, the government needs to keep up with the latest information technology and provide citizens with more convenient access to government information and services. West21 analyzed 2166 government Web sites from 198 different nations and presented an updated global e-government report in three consecutive years. The criterions used in the study to compare these aforementioned sites include factors such as publication, database, audio or video clip, restriction, foreign language, privacy, security, credit card payment, number of online services, etc. Twenty-one percent of the visited Web sites actually provide online services. West's definition of online services, however, included only those services that were fully executable online. In other words, if a citizen has to print out a form and mail/take it to a government agency to execute the service, it is not counted as an online service.

In a 2003 updated report, Singapore was ranked at the top of 198 countries. The rest of the top five nations that scored well in terms of e-government service included the United States, Canada, Australia, and Taiwan. This report confirmed the effort made by the Taiwanese government in rendering its electronic services. However, the high services score does not guarantee popularity. The usage of online Internet tax filing in Taiwan is still not satisfactory at this stage.

2.2. Tax-filing methods in Taiwan

As discussed earlier, there are three major tax-filing methods in Taiwan: manual filing, 2D bar code filing, and the Internet tax filing. The later two are usually considered electronic tax filing. For manual filing, taxpayers fill out a standard printed form, usually by hand. Complex calculations are performed using either pencil and paper or calculator. The tax agencies use either manual data entry or image processing to input taxpayers' data into their computers. This traditional filing method consumes large amounts of time and effort of both taxpayers and the tax agencies.

The 2D bar code filing was used around the same time as the Internet filing. These two electronic filing methods provide the taxpayer an opportunity to use software to run tax return preparation with a CD-ROM or through an Internet download. With tax-filing software, the data entry errors and calculation errors can be automatically detected, and the best tax return option is provided for the taxpayer. Using 2D bar code filing, the taxpayers need to print out two to three pages of a paper form with a 2D bar code, which encodes all data (nearly 1000 bytes) within the form. The tax agencies receive the paper form by mail and then scan the 2D bar code to input taxpayers' data into their computer system for further operation. While in Internet filing, the taxpayers file directly online, and data are transferred into the agencies' computer system automatically.

Hwang1 adapted the Haines and Petit instrument22 to conduct an experiment and survey to evaluate the above three tax-filing methods. The results show that the user satisfaction is greater in 2D filing than in Internet and manual filing. The survey indicates that the major users of electronic filing are males who have a college education, who have more than three years of computer experience, and one to three years of Internet experience. Wang14 added a new construct, “perceived credibility,” and critical individual difference variables to extend the TAM study in the context of electronic tax-filing systems. Based on a sample of 260 users, obtained through telephone interviews, Wang's study results show strong support of the extended TAM.

2.3. Models of technology acceptance

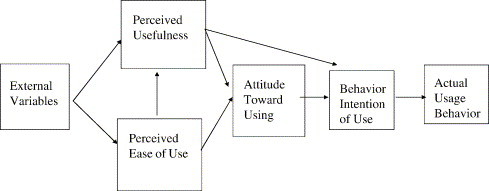

The TAM (see Fig. 1 ) adapts the theory of reasoned act (TRA) model to explore the IT acceptance. TAM and TRA state that an actual behavior is determined by the intention to perform that behavior. Intention itself is determined by the individual's attitude toward the behavior. TAM indicates both PU and PEOU as key independent variables that determine or influence potential users' attitudes (ATT) toward IT intention of use (BI). Davis23 called for future research to consider the role of additional external variables that will influence PU and PEOU. Despite the great success of this widely applied theoretical model, mixed results of these external variables were found in the IS field.

Fig. 1.

Technology Acceptance Mode (Davis et al.43).

Lee et al.3 summarized from 101 articles published by leading IS journals and conferences from 1986 to 2003 and classified the external variables of TAM into the following four categories. They include (1) Rogers'24 five innovation characteristics, which include relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, observability, and trialability; (2) individual differences such as self-efficacy, personal innovativeness, subjective norms, computer anxiety, computer attitude, and prior experience; (3) system quality, including output or information quality, end user support, and result demonstrability; and (4) others such as voluntariness, perceived enjoyment, and management support, etc. This research explained that the antecedents of PU and PEOU are important in the TAM research area.

DeLone and McLean (D&M) introduced the information systems success model based on a review of more than 180 published papers.5 This model organized a rich, but somewhat confusing, body of research and provided a comprehensive view of IS success. Since 1992, nearly 300 articles in leading journals have referred to or adopted the D&M IS success model.6 Among these success variables, the conceptualization of the “use” construct was especially confusing in the original D&M model. The IS use was defined as the consumption of IS output which is consistent with a process model of IS success. Seddon13 identifies three distinct models intermingled in the D&M model, each reflecting a different interpretation of IS use. From a process model of IS success, “use” depicts the sequence of events relating to an IS. A second meaning is a variable that proxies for the benefits from “use.” A third meaning is the dependent variable in a variance model of future IS use in which the role of IS use is used to describe behavior. To avoid the confusion associated with D&M, this study used D&M-like6 quality antecedents to summarize the external variables of the TAM acceptance model for the Internet tax-filing system.

2.4. Quality antecedents

During the last several years, one of the most important issues in business is “quality.” Regardless of the industry (manufacturing, healthcare, education, or government), professionals of all kinds are wrestling with the issue of how to improve their quality in order to gain competitive advantage. However, “quality” means different things to different people under different contexts. Therefore, researchers should develop an appropriate scale contextually when referring to the quality.

Taylor defined quality as “a user criterion that has to do with excellence or in some cases truthfulness in labeling.”25 From the customer view, quality was considered to meet a customer's expectations of the product or service being delivered.26., 27. D&M embraced the most frequently cited quality factors of the information system in the IS academic research into their updated IS success model: the ISQ, IQ, and Service quality.6 ISQ is associated with the issue of whether the technical components (including hardware, software, help screens, and user manuals) of delivered IS provide the quality of information and service required by stakeholders. ISQ is often measured by multi-items such as useful functionality, accessibility, flexibility, integration among sub-systems, response time, reliability, accuracy of data processing, ease-of-use, and ease-of-learning.5., 11., 28., 29. The IQ represents the users' perception of the output quality generated by an information system and includes such issues as the relevance, timeliness, and accuracy.6., 13.

Service quality was introduced in the IS originally to measure the quality of services provided by IT departments in organizations. Researchers have applied and tested the SERVQUAL measurement instrument from marketing30., 31. into the D&M original model. Some debates32 challenged the SERVQUAL metric, identifying “problems with the reliability, discriminant validity, convergent validity, and predictive validity of the measure.” Service quality was often measured by tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. D&M6 suggested that each of the three quality dimensions (IQ, ISQ, and Service Quality) has different weights depending upon the level of analysis. They also suggested, “To measure the success of a single system, INFORMATION QUALITY or SYSTEM QUALITY may be the most important quality component. For measuring the overall success of the IS department, as opposed to individual systems, SERVICE QUALITY may become a more important variable.”6

Credibility can be simply defined as believability. Credibility was seen as a perceived quality of a computer system.6., 33. In the Internet era, security and privacy issues have been the primary concerns to Internet users. A credible Web site needs to safeguard personal information from unauthorized access or disclosure, accidental loss, and alteration or destruction. Studies indicated that the users' perceptions of credibility regarding security and privacy were found to influence the user's intention to use Web-based IT application.14., 34., 35., 36. Wang14 further explained that “perceived fears of divulging personal information and users' feelings of insecurity provide unique challenges to planners to find ways in which to develop users' perceived credibility of electronic tax-filing systems.” Therefore, perceived credibility is considered as another important quality factor in the Internet tax-filing system.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Research model

Lucas37 concluded that unused systems are failures. Therefore, it is reasonably assumed that heavily used systems are successful. Different constructs influence the usage of various systems differently. Lewis4 predicted system usability in three dimensions: system usefulness, interface quality, and information quality. D&M used IQ, ISQ, and Service quality, while TAM used PU, PEOU, attitude, and intention to forecast the usage. However, only a few empirical studies11., 38., 39. were done to find causality among these constructs.

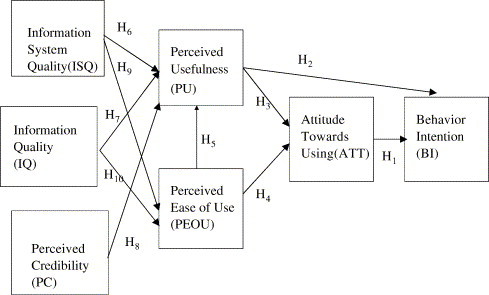

Fig. 2 depicts the research model of this study. The development of our research model is based on two points of view. The first point of view, from TAM, is that an IT usage is determined by the beliefs that a user holds about the PU and PEOU of the system. Meanwhile, external variables of TAM affect usage behavior only through their impact on beliefs of PU and PEOU.41., 42. The second viewpoint is the quality antecedents of usage from D&M6 and Wang.14 The authors then extracted part of the Davis model that has been validated by many studies: PU and PEOU impact on ATT, and the ATT impacts on BI. The external variables that impact PU and PEOU generated significant and insignificant mixed results.3 As a result, the external variables are summarized using D&M-like5 quality antecedents of use and satisfaction. The decision not to use the entire D&M model was to avoid the confusion of use and benefits of the model.

Fig. 2.

Research model.

DeLone and McLean6 included the service quality aspect of e-commerce; however, the Internet tax-filing system is not a commercial product. Since its first launching in 1998 until now, most users of the Internet tax-filing system are assumed to be early adopters who have greater capability to deal with abstractions and rationality, and are assumed to have a more favorable attitude toward changes than later adopters.24 To this end, they may emphasize service quality less. Meanwhile, service quality is also involved in some controversial issues. Due to the aforementioned issues, service quality was not included in this study.

In the Internet era, research that focuses on trust dimensions has received a lot of attention. Trust is an expectation that who one chooses to trust will not behave opportunistically by taking advantage of the situation.34 However, G2C e-service is different from B2C e-commerce. Government will behave in a dependable, ethical, and socially appropriate manner. Therefore, instead of the trust construct,34 Wang's14 perceived credibility regarding security and privacy that influenced the user's intention of using electronic tax filing is included in this study. The quality antecedents in our model mimic that of the D&M6 structure, but separate variables related to PU, PEOU, and PC to fit in the context of the Internet tax-filing system.

Consistent with these aforementioned two points, the authors propose that the constructs hypothesized (e.g., IQ, ISQ, and PC) affect the use of Internet tax filing indirectly through their effect on PU and PEOU. The definition of IQ, ISQ, and PC in this study will be explained in the next section. Considering that the filing of individual income taxes is done annually, the actual behavior of continued usage is excluded in this study. The dependent variable is the construct of “behavior intention,” which means respondents' intention to use Internet filing in the next year. Altogether, ten hypotheses are formulated below:

H1

User attitude on using the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the users' intention to file their tax on Internet next year.

H2

The PU of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the users' intention to file their tax on Internet next year.

H3

The PU of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the users' attitude on using the Internet tax-filing system.

H4

The PEOU of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the users' attitude on using the Internet tax-filing system.

H5

The PEOU of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the PU of using the Internet tax-filing system.

H6

The ISQ of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the PU of using the Internet tax-filing system.

H7

The IQ of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the PU of using the Internet tax-filing system.

H8

The PC of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the PU of using the Internet tax-filing system.

H9

The ISQ of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the PEOU of using the Internet tax-filing system.

H10

The IQ of the Internet tax-filing system positively affects the PEOU of using the Internet tax-filing system.

A taxpayer will prepare and file his/her tax on the Internet only if the filing method assists him/her in completing tax filing effectively. Therefore, this study assumes that PU of Internet tax filing will positively affect the attitude and intention of using the system. In addition, the authors assume that the easier it is to learn and use Internet tax filing, the more willing taxpayers will be to file their tax on the Internet. As suggested by Davis et al.43 and Venkatesh and Davis,44 PEOU is a direct determinant of PU. All else being equal, the less effort spent on learning the Internet tax-filing system, the more it is perceived to be useful.

Higher ISQ, such as faster response, error reduction, tax calculation, what-if analysis, easy navigation of the Internet tax-filing system, and ease of locating needed information, is assumed to enhance taxpayers' performance and therefore reinforces the perceived benefits of the system. Before computer-based tax-filing software, most taxpayers paid, and some still pay, professionals to prepare their taxes each year in order to get higher output or information quality (e.g., accurate and complete tax information, suitable format of prepared tax form, understandable presentation of tax-filing steps). Therefore, higher IQ is assumed to enhance taxpayers' performance on tax-filing output and therefore reinforce their perceived usefulness of the system. Perceived credibility may reduce risk perceptions (e.g., personal information disclosure) in users' minds and consequently enhance taxpayers' confidence in Internet filing. Both IS and ISQ factors may reduce the user's effort spent in IT usage and are assumed to positively impact user's PEOU of the system.

3.2. Measurement

Multiple items were used for measuring the research variables using a seven-point Likert scale. The selected items in the instrument for each construct were mainly adapted from prior studies to ensure the content validity. A draft questionnaire was translated into Chinese by a bilingual research associate. The translation accuracy was then refined and verified by two MIS professors. For content and preface validity, a focus group comprised of five experienced Internet tax-filing users was held to review the questionnaire and derive appropriate quality attributes that the Internet tax-filing system should possess. The modified version was then examined by two senior IS managers in e-government for wording improvement. Table 2 summarized the operational definition of constructs and sources of the questionnaire items. The final instrument is included in the appendix section.

Table 2.

Operational definition of questionnaire constructs

| Construct | Operational definition | Number of item | Source of items |

|---|---|---|---|

| BI | The taxpayer's likelihood to use the Internet tax-filing system | 3 | Taylor and Todd45 |

| ATT | Individual preferences and interests via feelings and evaluations regarding the Internet tax-filing system | 3 | Davis 46 |

| PU | The degree of taxpayers' perceived benefits of filing tax by Internet tax filing | 4 | Davis;46 +Focus group |

| PEOU | The degree of a user's belief that the use of the Internet tax-filing system to be free of effort | 4 | Davis46 |

| ISQ | Usefulness of functions, process reliability, response time, and ease of navigation | 4 | Bailey and Pearson;28 Belardo et al.;29 DeLone and McLean;5 Lin and Lu;11 +Focus group |

| IQ | Information reliability, relevance, adequacy, and understandability | 4 | King and Epstein;47 Miller and Doyle;48 DeLone and McLean;5 Rai et al.;49 +Focus group |

| PC | The extent of user confidence on the Internet tax-filing system with the ability of protecting the user's personal information and security | 2 | Wang14 |

Behavior intention is defined as the user's likelihood to use the Internet tax-filing system in the next tax season and was measured by three items adapted from Taylor and Todd.45 Attitude is defined in terms of individual preferences and interests via feelings/evaluations regarding use of the Internet tax-filing system, and it was measured by three items adapted from Davis.46 PU was defined as the degree to which a person believes that using the Internet tax-filing system would enhance/improve his/her job performance.46 According to the taxpayer focus group, the main benefits of Internet filing are greater error reduction in preparing tax return, better time saving on tax calculation and form preparation, lower communication costs, and faster refund than conventional filing tax method. Consequently, these items were used to measure the PU of Internet tax filing. PEOU was defined as the degree to which a user expects the use of the Internet tax-filing system to be free of effort46 and was measured by four items adapted from Davis' study.46

ISQ is judged globally by the degree to which the technical components (including software, help screens, and user manuals) of Internet tax filing provide the quality information and service required by users. ISQ is often measured by attributes such as useful functionality, accessibility, flexibility, integration among sub-systems, response time, reliability, accuracy of data processing, ease-of-use, and ease-of-learning.5., 11., 28., 29. After screening out the overlap of PU and PEOU, and modifying according to input from the focus group, ISQ, in this study, was measured by four attributes: usefulness of functions, process reliability, response time, and ease of navigation.

IQ is judged globally by the degree to which users are provided with quality information with regard to their needs. IQ is often measured by attributes such as accuracy, precision, understandability, readability, clarity, suitable format, completeness, relevancy, timeliness, and freedom from bias.5., 47., 48., 49. After screening out the overlap of PU and PEOU, and modifying according to input from the focus group, IQ, in this study, was measured by four attributes: information reliability, relevance, adequacy, and understandability. Finally, perceived credibility was defined as the extent of users' confidence in the Internet tax-filing system's ability to protect the user's personal information and security. These aforementioned two items were adapted from Wang.14

According to Hwang's2 survey results, the dominant users of electronic tax filing in Taiwan were men with a college education, and with years of computer-related experiences. To this end, appropriate sampling was employed in this research. Approximately 200 questionnaires were distributed to faculty and part-time undergraduate students of four universities who had previously filed their income tax using Internet filing.

4. Results

Among 200 subjects, 141 respondents completed the questionnaires, a 70.5% response rate. Detailed demographic data are provided in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Demographic data

| Measure | Items | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 61 | 43.3 |

| Male | 80 | 56.7 | |

| Education | Under graduate | 78 | 55.3 |

| Graduate | 63 | 44.7 | |

| Age | 20–30 | 45 | 31.9 |

| 30–40 | 72 | 51.1 | |

| 40–50 | 16 | 11.3 | |

| 50–60 | 5(3 N/A) | 5.7 | |

| Job | Public section | 81 | 57.4 |

| Private section | 57 (3 N/A) | 42.6 | |

| Time of using computer per week | < 14 hours | 31 | 22.0 |

| 14–28 hours | 22 | 15.6 | |

| > 28 hours | 88 | 62.4 |

4.1. Assessing the reliability and validity

The composite reliability measure gives a truer indication of reliability than the traditional measure of alpha coefficient as it takes into account the possibility that the indicators may have different factor loadings and error variances.50., 52. The value of composite reliabilities higher than the threshold level of 0.7 was deemed to provide satisfactory reliability. In this research, the composite reliability for each construct in the measurement model was above 0.90 (see Table 4 ). Further, another measure of reliability is the average variance extracted. This measure reflects the overall amount of variance in the indicators accounted for by the latent construct. Higher variance extracted value occurs when the indicators are truly representative of the latent construct. The average variance extracted measure is a complementary measure to the construct reliability value. Guidelines suggest that the average extracted variance value should exceed a 0.50 level for a construct, which means more than one-half of the variances observed. In Table 4, average variances extracted for all constructs were above 0.70. As a result, it is concluded that all the constructs used in this study were highly reliable.

Table 4.

Reliability results

| Items | Mean | SD | Factor loading in each item | Composite construct reliabilities | Average variance extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI1, BI2, BI3 | 5.722 | 0.877 | 0.97, 0.94, 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.85 |

| ATT1, ATT2, ATT3 | 5.731 | 0.964 | 0.95, 0.94, 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.85 |

| PU1, PU2, PU3, PU4 | 5.758 | 0.934 | 0.95, 0.94, 0.99, 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.94 |

| PEOU1, PEOU2, PEOU3, PEOU4 | 5.762 | 0.941 | 0.94, 0.98, 0.95, 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.90 |

| ISQ1, ISQ2, ISQ3, ISQ4 | 5.838 | 1.019 | 0.85, 0.91, 0.88, 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.78 |

| IQ1, IQ2, IQ3, IQ4 | 5.410 | 1.260 | 0.92, 0.95, 0.97, 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.88 |

| PC1, PC2 | 4.448 | 1.451 | 0.72, 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.54 |

The constructs employed were further examined using convergent and discriminant validity analysis to validate the prediction of taxpayers' acceptance of the Internet tax-filing system. Convergent validity is assessed by testing whether the factor loading that relate each indicator to the construct of interest are all significant,52., 53. i.e., t values greater than 1.96 (P < 0.05). In this study, all t values are between 3.13 and 33.20, which indicates good convergent validity. Discriminant validity is the degree to which measures of different concepts are distinct. To test discriminant validity, Fornell and Larcker54 suggested that the squared correlations between two different measures in any two constructs should be statistically lower than the variance shared by the measures of a construct. All shared variances between any two different constructs were, in fact, less than the amount of variance extracted by one of the two constructs (see Table 5 ). Therefore, the constructs of the proposed research model exhibit adequate discriminant validity. Table 6 contains the LISREL-calculated correlations among the constructs.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity test

| BI | ATT | PU | PEOU | ISQ | IQ | PC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | 0.85 | ||||||

| ATT | 0.43 | 0.85 | |||||

| PU | 0.38 | 0.80 | 0.94 | ||||

| PEOU | 0.28 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.90 | |||

| ISQ | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.78 | ||

| IQ | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.88 | |

| PC | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 054 |

Table 6.

LISREL standardized correlation matrix

| BI | ATT | PU | PEOU | ISQ | IQ | PC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | 1 | ||||||

| ATT | 0.655985 | 1 | |||||

| PU | 0.616562 | 0.892429 | 1 | ||||

| PEOU | 0.532257 | 0.842758 | 0.870534 | 1 | |||

| ISQ | 0.369037 | 0.557516 | 0.520101 | 0.516682 | 1 | ||

| IQ | 0.281095 | 0.490438 | 0.517366 | 0.512386 | 0.589147 | 1 | |

| PC | 0.116324 | 0.132675 | 0.151188 | 0.144887 | 0.061438 | 0.12032 | 1 |

4.2. LISREL model and hypotheses testing

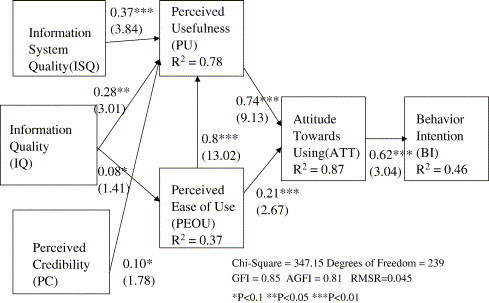

The LISREL analysis of the path model developed in this study shows reasonable fit for the structural model (see Fig. 3 , χ 2/df = 1.453, GFI = 0.85, AGFI = 0.81, RMSR = 0.045, NFI = 0.93, NNFI = 0.97).52., 55. The explanatory power of the model for individual construct was examined using the resulting R 2 for PU, PEOU, ATT, and BI are 78%, 37%, 87%, respectively. Two hypotheses, H2 (beta = 0.06, t = 0.30) and H9 (beta = 0.06, t = 0.94), were not supported by data. In other words, the influence of ISQ on PEOU was not significant, and neither was the influence of PU on BI. However, other hypotheses, H1 (beta = 0.62, t = 3.04), H3 (beta = 0.74, t = 9.13), H4 (beta = 0.21, t = 2.67), H5 (beta = 0.80, t = 13.02), H6 (beta = 0.37, t = 3.84), H7 (beta = 0.28, t = 3.01), H8 (beta = 0.10, t = 1.78), and H10 (beta = 0.08, t = 1.41), were significantly supported by the data. The results of hypotheses testing are summarized in Table 7 .

Fig. 3.

LISREL model.

Table 7.

Hypotheses testing result

| Ha | Relationships | Results | Prior Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ATT→BI | Supported (P < 0.01) | Davis;46 Davis et al.;43 Dishaw and Strong;66 Hu, et al.;67 Karahanna, et al.;42 Taylor and Todd45 |

| H2 | PU→BI | Not supported | Davis;46 Davis et al.;43 Hu et al.;67 Lederer, et al.56 (NS); Taylor and Todd;45 Venkatesh and Davis44,68 |

| H3 | PU→ATT | Supported (P < 0.01) | Davis;46 Davis et al.;43 Taylor and Todd;45 Chau;57 Karahanna, et al.;58 Lederer et al.56 |

| H4 | PEOU→ATT | Supported (P < 0.01) | Davis;46 Davis et al.;43 Taylor and Todd;45 Chau;57 Karahanna, et al.;58 Lederer et al.56 |

| H5 | PEOU→PU | Supported (P < 0.01) | Davis et al.;43 Venkatesh and Davis44 |

| H6 | ISQ→PU | Supported (P < 0.01) | Shih40 |

| H7 | IQ→PU | Supported (P < 0.05) | Seddon and Kiew;38 Fraser and Salter;39 Venkatesh and Davis;68 Rai et al.49 |

| H8 | PC→PU | Marginally supported (P < 0.1) | Wang;14 Shih40 |

| H9 | ISQ→PEOU | Not supported | Lucas and Spitler;12 Lin and Lu11 |

| H10 | IQ→PEOU | Marginally supported (P < 0.1) | Vessey69., 70. |

| Not supported (NS): P value is not significant. | |||

The multicollinearity among independent variables may reduce any single independent variable's predictive power.51 As a rule of thumb, a tolerance value less than 0.20 indicates a multicollinearity problem. In this study, multicollinearity was not a serious concern in our proposed model, since all relevant checks returned a tolerance value above 0.2 for all independent variables (see Appendix A).

5. Discussion

This study confirmed most of TAM's conclusions in previous research of applying other IT (H1, H3, H4, H5). In other words, the results from this proposed study imply that it is suitable to apply TAM in the G2C area. In this study, the authors found that the PU has no direct impact on BI but has significant influences on ATT, which consequently impacts on BI of using the system. That is, the effect of PU on BI was mediated through ATT. This finding is consistent with the study from Lederer et al.56 on WWW acceptance.

Both PU and PEOU have significantly positive impacts on ATT of using the system. The effect of PU (b = 0.74) is twice the significance of PEOU (b = 0.21) on ATT. This finding was consistent with prior research results43., 45., 46., 57., 58. but was contrary to electronic tax-filing system acceptance.14 In Wang's research, PEOU is more important than PU on taxpayers' acceptance of electronic tax filing. The possible explanations include the following: First, the effect of PEOU on IT usage often decreases with user familiarity with the IT.59 Only experienced Internet tax-filing taxpayers were selected in this study, and most of them were already familiar with the operation of the Internet tax-filing method. Therefore, the effect of PEOU on Internet filing acceptance is not as important as PU. Second, the respondents' education level in this study was, on average, higher than that in Wang's study. In general, higher education assures more computer and Internet experience. Therefore, PEOU may not be an important concern for these respondents.

The IQ was found to have a positive impact on PU and PEOU in the proposed study, which is consistent with previous studies.38., 39. The ISQ was found to have an association with PU instead of PEOU. This result is contrary to the findings of Lucas and Spitler12 and Lin and Lu.11 Lucas and Spitler12 found that users' PEOU declined significantly as ISQ of workstations did. Lin and Lu11 found that the response time of a Web site greatly affects the user's belief of PU and PEOU, and affects on PEOU more than on PU. The possible explanation may be that experienced computer/Internet users have less patience for low ISQ. A slow response system is considered to be useless and not worth the wait compared with a difficult-to-use system. Lastly, the empirical result shows that PC has created a certain impact on PU. This finding is also consistent with Shih40 and Wang.14 The taxpayers were concerned with security and privacy issues during uploading tax return data and payment phases.

6. Limitation and implications

This empirical study has five limitations. First, because of personal confidentiality concerns, general taxpayers were unwilling to respond to the questionnaire. Therefore, a convenient sampling method, according to Hwang's2 study, rather than a random sampling method was employed in this study. Because highly educated taxpayers who were experienced with the Internet tax-filing system were selected as the survey sample, the external validity of the research results may be limited. Second, the overall goodness-of-fit of the proposed structural model (GFI = 0.85) is slightly lower than the commonly cited threshold: GFI > 0.9.51 Though most published papers in leading MIS journals seldom show excellent fit values in all the indices,60 a GFI value of 0.85 or larger is acceptable for such an exploratory study.55 Therefore, the proposed model may present a reasonable goodness-of-fit as an exploratory study.

Although IS service quality was the subject of controversial debate,30., 31., 32., 61., 62., 63., 64. D&M6 included service quality in the e-commerce success model. However, this study did not include service quality because of the sample subjects and because the attention was focused on IQ, ISQ, and PC of the Internet tax-filing system of G2C. To promote Internet filing with all taxpayers, service quality may play an important role. Therefore, future research should extend to include service quality as a quality antecedent of TAM.

Finally, instead of PC positively impacting PEOU, Ong, et al.36 and Wang14 found that PEOU positively influences users' PC in interaction with IS. The authors also tested the revised LISREL model with this linkage. However, GFI of the revised model decreased dramatically from 0.85 to 0.73, which indicated that the presence of the relationship between PEOU and PC in the proposed model could not significantly explain the obtained data results. The inadequate results may be caused by the difference in the sampling characteristic or the different information system applied. Future research could also be extended to examine the linkage between PEOU and PC in the e-government service context.

The implications of this study are twofold: the first is to retain the current users; the second is to create new users. Since the current experienced users weigh PU heavily, the NTA should propose some promotional plans that capitalize on the benefits of using the Internet tax-filing system in order to retain/keep the current users. The PU has a three times stronger impact than PEOU (PU: 0.74, PEOU: 0.21) on attitude toward the system, which then influences the intention to use the system next year and afterwards. To increase the PU of using the Internet tax-filing system, the tax agency needs to provide a better ISQ, IQ, and PC. For example, faster response time of the Internet tax-filing system will lead users to perceive higher usefulness of the system. Under budget constraints, the priority of the improvement should start from ISQ, then IQ, and finally PC, respectively, since each has an impact on PU as ISQ: 0.37; IQ: 0.28; and PC: 0.10. Besides, the empirical results also show that the quality factors (e.g., IQ, ISQ,) of the Internet tax-filing system have positive impacts on taxpayers' PEOU of using the system. To create new users, the NTA needs to provide more training courses and simplify the interface design to make the system easier to use.

For costs consideration, Taiwanese government often outsourced most of its IS systems to slim sown the human resource overhead. The e-government projects are outsourced to professional computer system's vendors. Without ongoing quality monitoring, e-government service may deviate, or depart somewhat, from citizens' requirements and expectations. The authors suggest that explicit statements of quality concern should be added in the future maintenance contract with e-government system providers. Moreover, the NTA should be responsible for the following jobs: (1) to define standards and prepare reliable quality measurements of ISQ, IQ, and PC. The instrument of this study may provide a good reference, (2) to apply different evaluation methods of the Internet tax-filing system to detect ongoing quality, and (3) to define a corrective action plan when quality levels deviate from the standards.

Though the e-government services in Taiwan are ranked in the top five worldwide, this may not guarantee public acceptance. To fulfill the concept of citizen as customer, there is still room for improvement. In Taiwan, there are about 3.8 million households using the Internet, and the registered online users number about 8.7 million. These are the major potential Internet tax-filing users.65 In addition, the number of 2003 Internet tax-filers doubled over that of 2002 (see Table 1). A major reason was the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Taiwan during the 2003 tax-filing season. Therefore, applying TAM to the Internet tax-filing system can lead to an understanding of public acceptance of the system and can shed some light on research of the G2C e-government system in the future.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Behavior Intention (BI)

BI1. I intent to file my tax on Internet in the next tax return season.

BI2. I intent to use Internet tax-filing system in my preparation of tax return in the next tax return season.

BI3. To the extent possible, I would try to file my tax on Internet in the next tax return season.

Attitude (ATT)

ATT1. Filing tax return on the Internet is a good idea.

ATT2. Filing tax return on Internet will be a pleasant experience.

ATT3. I like the idea of Internet tax-filing.

Perceived Usefulness (PU)

PU1. Using the Internet tax-filing enables me to accomplish my tax filing more quickly

PU2. Using the Internet tax-filing enables me to accomplish my tax filing in lower communication cost

PU3. Using the Internet tax-filing enables me to reduce the error in my tax filing process

PU4. Using the Internet tax-filing enables me to get refund from tax agency more quickly

Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

PEOU1. Learning to use the Internet tax-filing software is easy for me.

PEOU2. I can use the Internet tax-filing software in a manner that allows me to get the appropriate information I want

PEOU3. My interaction with the Internet tax-filing software is clear and understandable

PEOU4. In general, I find the Internet tax-filing software easy-to-use.

Information System Quality (ISQ)

usefulness of functions, reliability, response time, and ease of navigation

ISQ1. The Internet filing system provides the useful functions as I need when I prepare and file my tax return.

ISQ2. When I prepare and file my tax return, the operation of Internet filing system is reliable.

ISQ3. When I prepare and file my tax return, the response of Internet filing system is quick.

ISQ4. When I prepare and file my tax return, I can navigate the system to finish my tax filing easily.

Information Quality (IQ)

IQ1. The Internet filing system provides the reliable information when I prepare and file my tax return.

IQ2. The Internet filing system provides the adequate information when I prepare and file my tax return.

IQ3. The Internet filing system provides the information which is easy to understand.

IQ4. The Internet filing system provides the relevant information as I need.

Perceived Credibility(PC)

PC1. Using the Internet filing system would not divulge my personal information.

PC2. I find the Internet filing system secure in preparing and filing tax returns.

Tolerance value for each dependent variable (dv) vs. independent variables (idv)

| dv | idv |

| PU | ISQ: 0.353 |

| IQ: 0.359 | |

| PC: 0.958 | |

| PEOU: 0.680 | |

| PEOU | ISQ: 0.383 |

| IQ: 0.384 | |

| ATT | PU: 0.5 |

| PEOU: 0.5 | |

| BI | ATT: 0.493 |

Notes and References

- 1.National Tax Administration (NTA), Taiwan. (2003). E-business: Current developments in the computerization of operations. Retrieved from http://www.ntx.gov.tw/english/e6.htm.

- 2.Hwang C.S. A comparative study of tax-filing methods: Manual, Internet, and two-dimensional bar code. Journal of Government Information. 2000;27(2):113–127. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee Y., Kozar K.A., Larson K.R.T. The Technology Acceptance Model: Past, present, and future. Communications of Association for Information Systems. 2003;12(Article 50):752–780. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis J.R. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction. 1995;7(1):57–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeLone W.H., McLean E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems Research. 1992;3(1):60–95. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLone W.H., McLean E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems. 2003;19(4):9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal R., Prasad J. Are individual differences germane to the acceptance of new information technologies? Decision Sciences. 1999;30(2):361–391. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brynjolfsson E. The contribution of information technology to consumer welfare. Information Systems Research. 1996;7(3):281–300. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin C.S., Wu S. Exploring the impact of online service quality on portal site usage. In: Sprague R.H., editor. Proceedings of the 35th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS-35. Big Island; Hawaii: 2002. pp. 2654–2661. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hitt L., Brynjolfsson E. The three faces of IT value: Theory and evidence. In: DeGross J.I., Huff S.L., Munro M.C., editors. Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems. Association for Information Systems; Atlanta, GA: 1994. pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin J.C.C., Lu H. Towards an understanding of the behavioral intention to use a Web site. International Journal of Information Management. 2000;20(3):197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas H.C., Spitler V.K. Technology use and performance: A field study of broker workstations. Decision Sciences. 1999;30(2):291–311. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seddon P.B. A respecification and extension of DeLone and McLean's model of IS success. Information Systems Research. 1997;8(3):240–253. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y.S. The adoption of electronic tax filing systems: An empirical study. Government Information Quarterly. 2002;20(4):333–352. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.New Zealand Government. (2000). E-government—A vision for New Zealanders. Retrieved September 1, 2003, from http://www.e-government.govt.nz/programme/vision.asp.

- 16.Turban E., King D., Lee J., Warketin M., Chung H.M. 2nd ed. Pearson Education, Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2002. Electronic commerce: A managerial perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sprecher M.H. Racing to e-government: Using the Internet for citizen service delivery. Government Finance Review. 2000;16(5):21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Momentum Research Group. (2000). Benchmarking the egovernment revolution. Retrieved September 5, 2003, from http://www.egovernmentreport.com.

- 19.Currie W.L. Meeting the challenge of Internet commerce: Key issues and concerns. In: Despotis D.K., Zopounidis C., editors. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of the Decision Sciences Institute: Integrating Technology and Human Decisions: Global Bridges into the 21st Century. 1999, July 4–7. pp. 355–357. (Athens, Greece) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilfoyle P. A vision of the future, public. Sector IT Insight. 1999;2(4):16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 21.West. (2003). Global e-government, 2003. Retrieved September 20, 2004, from http://www.insidepolitics.org/egovt03int.html.

- 22.Haines V.Y., Petit A. Conditions for successful human resource information systems. Human Resource Management. 1998;36(2):261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis F.D. User acceptance of information technology: System characteristics, user perceptions and behavior impacts. International Journal of Man–Machine Studies. 1993;38(3):475–487. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers E.M. 4th ed. Free Press; New York: 1995. Diffusion of innovations. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor R.S. Ablex Publishing; Norwood, NJ: 1986. Value-added processes in information systems. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gitlow H., Gitlow S., Oppenheim A., Oppenheim R. Irwin; Homewood, IL: 1989. Tools and methods for the improvement of quality. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozeki K., Asaka T., editors. Handbook of quality tools: The Japanese approach. Productivity Press; Cambridge: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey J.E., Pearson S.W. Development of a tool for measuring and analyzing computer user satisfaction. Management Science. 1983;29(5):530–545. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belardo S., Karwan K.R., Wallace W.A. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Information Systems. 1982. DSS component design through field experimentation: An application to emergency management; pp. 93–108. (Ann Arbor, MI) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt L.F., Watson R.T., Kavan C.B. Service quality: A measure of information systems effectiveness. MIS Quarterly. 1995;19(2):173–187. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kettinger W.J., Lee C.C. Perceived service quality and user satisfaction with the information services function. Decision Sciences. 1994;25(6):737–766. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dyke T.P., Prybutok V.R., Kappelman L.A. Cautions on the use of the SERVQUAL measure to assess the quality of information systems services. Decision Sciences. 1999;30(3):877–892. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fogg B.J., Tseng H. Proceedings of the CHI99 Conference on Human Factors and Computing Systems. ACM Press; 1999. The elements of computer credibility; pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gefen D., Karahanna E., Straub D.W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly. 2003;27(1):51–91. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salisbury D.W., Pearson R.A., Pearson A.W., Miller D.W. Perceived security and World Wide Web purchase intention. Industrial Management & Data Systems. 2001;101(4):165–176. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ong C.S., Lai J.Y., Wang Y.S. Factors affecting engineers' acceptance of asynchronous e-learning systems in high-tech companies. Information & Management. 2004;41(6):795–804. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucas H.C.J. Columbia University Press; New York: 1981. Implementation: The key to successful information systems. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seddon P.B., Kiew M.Y. A partial test and development of the DeLone and McLean model of IS success. In: DeGross J.I., Huff S.L., Munro M.C., editors. Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems. Association for Information Systems; Atlanta, GA: 1994. pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraser, S. G., & Salter, G. (1995). A motivational view of information systems success: A reinterpretation of DeLone and McLean's model. Paper presented at the Australian Conference on Information Systems, Curtin University, Western Australia.

- 40.Shih H.P. An empirical study on predicting user acceptance of e-shopping on the Web. Information & Management. 2004;41(4):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fishbein M., Ajzen I. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1975. Attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karahanna E., Straub D.W. The psychological origins of perceived usefulness and ease-of-use. Information & Management. 1999;35(4):237–251. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis F.D., Bagozzi R.P., Warshaw P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science. 1989;35(8):982–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venkatesh V., Davis F.D. A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: Development and test. Decision Sciences. 1996;27(3):451–481. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor S., Todd P.A. Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Quarterly. 1995;19(4):561–570. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly. 1989;13(3):319–339. [Google Scholar]

- 47.King W.R., Epstein B.J. Assessing information system value. Decision Sciences. 1983;14(1):34–51. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller J., Doyle B.A. Measuring effectiveness of computer based information systems in the financial services sector. MIS Quarterly. 1987;11(4):107–124. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rai A., Lang S.S., Welker R.B. Assessing the validity of IS success models: An empirical test and theoretical analysis. Information Systems Research. 2002;13(1):50–72. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson J.C. An approach for confirmatory measurement and structural equation modeling of organizational properties. Management Science. 1987;33(4):525–541. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hair J.F., Anderson R.E., Tatham R.L., Black W.C., editors. Multivariate Data Analysis. 5th ed. Prentice-Hall; New Jersey: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bagozzi R.P., Yi Y., Phillips L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1991;36(3):421–458. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Straub D.W. Validating instruments in MIS research. MIS Quarterly. 1989;13(2):147–169. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Browne M.W., Cudeck R. In: Alternative ways of assessing model fit in publishing in the testing structural equation models. Bollen K.A., Long S., editors. Sage Publications; CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lederer A., Maupin D.J., Sena M.P., Zhuang Y. The Technology Acceptance Model and the World Wide Web. Decision Support Systems. 2000;29(3):269–282. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chau P.Y.K. An empirical assessment of a modified Technology Acceptance Model. Journal of Management Information Systems. 1996;13(2):185–204. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karahanna E., Straub D.W., Chervany N.L. Information technology adoption across time: A cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Quarterly. 1999;23(2):182–213. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Venkatesh V., Morris M.G., Davis G.B., Davis D.F. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly. 2003;27(3):425–478. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boudreau M., Gefen D., Straub D.W. Validation in IS research: A state-of-the-art assessment. MIS Quarterly. 2001;2(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang J.J., Klein G., Carr C.L. Measuring information system service quality: SERVQUAL from the other side. MIS Quarterly. 2002;26(2):145–167. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kettinger W.J., Lee C.C. Pragmatic perspectives on the measurement of information systems service quality. MIS Quarterly. 1997;21(2):223–241. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Dyke T.P., Kappelman L.A., Prybutok V.R. Measuring information systems service quality: Concerns on the use of the SERVQUAL questionnaire. MIS Quarterly. 1997;21(2):195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watson R.T., Pitt L.F., Kavan C.B. Measuring information systems service quality: Lesson from two longitudinal case studies. MIS Quarterly. 1998;22(1):61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 65.FIND. (2003). Retrieved September 20, 2004, from http://www.find.org.tw/0105/howmany/howmany_disp.asp?id=61.

- 66.Dishaw M.T., Strong D.M. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model with task-technology-fit constructs. Information & Management. 1999;36(1):9–22. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu P.J., Chau P.Y.K., Liu Sheng O.R., Tam K.Y. Examining the Technology Acceptance Model using physician acceptance of telemedicine technology. Journal of Management Information Systems. 1999;16(2):91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Venkatesh V., Davis F.D. A theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science. 2000;46(2):186–204. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vessey I. Cognitive fit: Theory-based analyses of the graphs versus tables literature. Decision Sciences. 1991;22(1):219–241. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vessey I. The effect of information presentation on decision making: A cost-benefit analysis. Information & Management. 1994;27(8):103–119. [Google Scholar]