Abstract

It is now appreciated that the range of ligands interacting with C-type lectin type receptors on antigen presenting cells includes endogenous self-molecules as well as pathogens and pathogen-derived ligands. Interestingly, not all interactions between these receptors and pathogenic ligands have beneficial outcomes, and it appears that some pathogens have evolved immunoevasive or immunosuppressive activities through receptors such as DC-SIGN. In addition to this, recent data indicate that the well-characterised macrophage mannose receptor is not essential to host defence against fungal pathogens, as previously thought, but has an important role in regulating endogenous glycoprotein clearance. New studies have also demonstrated that different ligand binding and/or sensing receptors collaborate for full and effective immune responses.

Abbreviations: APC, antigen-presenting cell; BDCA, blood DC antigen; CLR, C-type lectin receptor; CRD, carbohydrate recognition domain; DC, dendritic cell; FN-II, fibronectin type II; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; ITAM, immunotyrosine activatory motif; MØ, macrophage; MHC-I, MHC class I; MHC-II, MHC class II; MR, mannose receptor; PRR, pattern recognition receptor; TLR, Toll-like receptor

Introduction

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the innate immune system include macrophages (MØs), dendritic cells (DCs) and B cells. These cells capture and process foreign antigens for presentation to T cells enabling efficient host defence and immunological memory. B cells are well equipped to recognize and take up a wide variety of antigens due to the presence of somatically variable surface immunoglobulins. DCs and MØs, however, rely on germ-line encoded cell-surface receptors to distinguish between harmless self antigens and pathogen-derived antigens against which immune responses are desirable [1]. Over the past number of years our understanding of APC cell surface receptor biology has increased greatly. In addition to the well-characterised opsonic receptors for γ-immunoglobulins (FcγRs) [2] and the complement receptors, such as complement receptor 3 (CR3) 3., 4., APCs of the myeloid lineage express an array of non-opsonic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which have evolved to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [5], including lipids, carbohydrates and proteins. In addition to this, APCs express receptors such as those of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily 6., 7., 8., which mediate interactions with host cells to regulate immune responses.

One of the most intensely studied families of PRRs is the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family, members of which respond to a wide variety of pathogen-derived material. These interactions lead to APC maturation and migration to lymph nodes for subsequent presentation of antigen-derived peptides to T cells (for a comprehensive review, see [9]). Although the TLRs play a central role in alerting APCs to the presence of pathogenic material it is not clear whether they are capable of capturing and taking up antigens [10•], and this function appears to be met by other families of PRRs, most notably the C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) [11•] and the scavenger receptors [12].

In recent years a wealth of information has emerged demonstrating diverse roles for CLRs during primary immune responses. These receptors function not only in pathogen recognition through the recognition of PAMPs but also in the recognition of endogenous ligands to mediate cell–cell interactions during immune responses. CLRs also bind soluble self antigens, leading to immune tolerance and maintenance of endogenous glycoprotein homeostasis [13]. Furthermore, co-operation between TLRs and CLRs has been demonstrated and it seems that appropriate immune responses rely on the interaction of many different antigen sensing and sampling mechanisms [14].

Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing APC discrimination of self and non-self antigens should facilitate a better understanding of aberrant immune phenomena such as autoimmunity and chronic inflammatory diseases as well as informing the design of vaccines and other immuno-modulatory drugs. In this article, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of CLR immunobiology and the contribution they make to interactions with both pathogenic and endogenous ligands. Data concerning molecular mechanisms of ligand discrimination by these receptors will also be discussed.

Characteristics of C-type lectin receptors

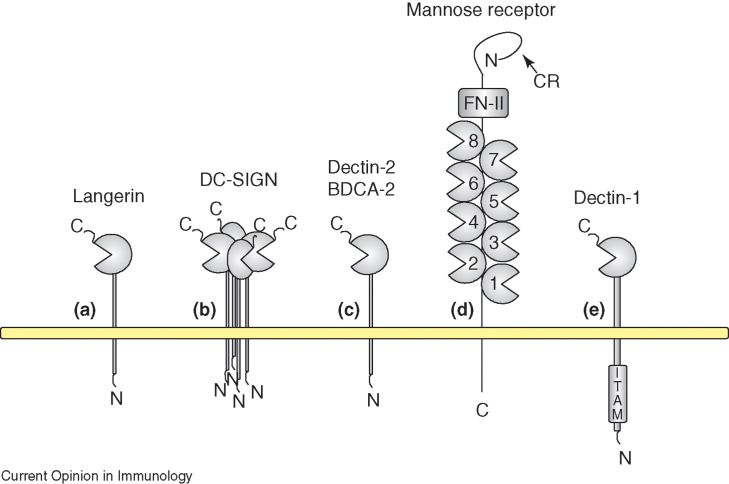

The term CLR defines carbohydrate-binding molecules that bind ligands in a Ca2+-dependent manner (see Table 1 ). CLRs expressed by MØs and DCs are predominantly type II transmembrane receptors with a single carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) such as DC-SIGN [15], the related murine receptor family termed SIGN-related (SIGNR)1-4 [16], dectin-2 [17], langerin [18] and BDCA-2 (blood DC antigen-2) [19]. In addition to this there are type I CLRs, such as mannose receptor (MR) and DEC-205, which have multiple lectin-like domains, although not all of these act as functional CRDs [20]. Dectin-1 is a type II CLR 21., 22. with a single CRD but differs from receptors such as DC-SIGN as it does not contain a standard Ca2+-dependent CRD and is more similar to the CLRs expressed by NK cells that bind MHC class I (MHC-I) and MHC-I-like counter-receptors [23] (Figure 1 ).

Table 1.

C-type lectin receptors that bind endogenous and exogenous ligands.

| Receptor | Type | Ligands (selected) | Expression | Regulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | I | Endogenous and exogenous ligands bearing mannose, fucose, N-acetyl glucosamine and sulphated sugars via cysteine rich domain | MØ, DC subsets, lymphatic and hepatic endothelium | ↑ PGE, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 ↓ IFN-γ, LPS | 54., 68., 69. |

| Endo-180 | I | Mannose, fucose and N- acetylglucosamine via CRD 2, collagen via FNII domain | Fibroblasts, MØ, subset of endothelial cells | Unknown | |

| DC-SIGN | II | HIV and other pathogens due to mannose type CRD. ICAM-2 and -3 via CRD. | DCs, alveolar and decidual MØ | ↑ IL-13 ↓ LPS | [70] |

| DC-SIGNR | II | Similar to DC-SIGN | Hepatic and lymphatic endothelium | Unknown | |

| SIGNR1 | II | Mannose-type CRD, dextran, Streptococcus pneumoniae CPS, Candida albicans, HIV, ICAM-3 | MZ MØ, peritoneal MØ | Unknown | |

| Langerin | II | Mannose, fucose, N-acetylglucosamine | Langerhans cells, subset of DCs | ↑ TGF-β↓ LPS, CD40-L | 71., 72. |

| BDCA-2 | II | Unknown | Plasmacytoid DCs | Unknown | |

| Dectin-2 | II | Conflicting evidence for mannose type ligands CD4+/CD25+ T-cell ligand | DC, MØ, Langerhans cells | Unknown | |

| Dectin-1/β-glucan receptor | II | β-1,3- and β-1,6-linked glucans from fungi T-cell ligand | MØ, DC, PMN, T cell | ↑ IL-4, IL-13 ↓ IL-10, LPS | [73] |

Abbreviations: MZ, marginal zone; PGE, prostaglandin E.

Figure 1.

The C-type lectin-like receptors expressed by dendritic cells and macrophages. These receptors permit interactions with pathogens and endogenous soluble proteins as well as cell-surface ligands expressed by T cells and anatomically distinct endothelial cells, such as those found in secondary lymphoid organs. Langerin (a), a type-II C-type lectin expressed exclusively by Langerhans cells, binds mannose-type ligands and delivers material to unique Birbeck granules. DC-SIGN (b), another type-II C-type lectin is expressed by both macrophages and DCs. It interacts with endogenous molecules, such as ICAM-2, on endothelial cells as well as ICAM-3 on T-cells, mediating intercellular adhesion. In addition, DC-SIGN binds pathogen-associated mannose-type carbohydrates found on viruses, bacteria and fungi. Multimerisation of DC-SIGN and other such receptors at the cell surface might facilitate high-affinity ligand binding. BDCA-2 (c), is a C-type lectin expressed exclusively by human plasmacytoid DCs and appears to play a role in regulating type-I IFN production by these cells, although ligands for this receptor are yet to be identified. Dectin-2, a murine C-type lectin which demonstrates sequence similarity with BDCA-2 has a role in regulating UV-induced tolerance. This might be due to interaction with an as yet unidentified ligand on CD4+CD25+ T cells. Mannose receptor (MR) (d), is a multi-functional type I receptor expressed by macrophages, DCs and endothelial cells. CRD 4 is the primary ligand-binding site for both endogenous and pathogen-derived mannosylated ligands. The CRD mediates interactions with sulphated carbohydrates found on endogenous ligands such as sialoadhesin and CD45. MR also mediates intercellular adhesion and can bind lymphocyte-expressed L-selectin. Dectin-1 (e), is a non-classical C-type lectin found primarily on macrophages, DCs and neutrophils. It binds β-glucans in a Ca2+-independent manner. Ligand-induced signalling mediated by the cytoplasmic ITAM motif leads to phagocytosis and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in co-operation with TLR-2.

True Ca2+-dependent CLRs fall into two broad categories, those recognizing mannose-type ligands and those recognizing galactose-type ligands, which can be defined at the molecular level by the presence of a distinctive triplet of amino acids within the CRD; EPN (in one-letter amino-acid code) for mannose-type receptors or QPD (in one-letter amino-acid code) for galactose-type receptors [24]. Additionally, receptors such as MR can recognize sulphated carbohydrates present on endogenous glycoproteins via a cysteine-rich domain independently of its CRD [25]. Dectin-1 binds β-1,3- and β-1,6-linked glucans, which are found in abundance in the cell walls of fungi, via a unique carbohydrate-binding mechanism that is not yet fully understood but has recently been shown to rely on a group of amino acids within a predicted β-sheet forming part of the CRD [26•].

Pathogenic and endogenous ligands for CLRs

Despite the existence of a wide range of CLRs with similar or overlapping ligand specificity, and the apparent ability of CLRs to bind both self and non-self ligands, each receptor appears to have distinct functions depending on where and when it is expressed, the degree of cell surface multimerisation and the context in which the ligand is recognized (i.e. in the presence or absence of an inflammatory signal through other receptors such as the TLRs).

The DC-SIGN family

DC-SIGN was originally characterised as a receptor interacting with intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-3 [15], mediating DC–T-cell interactions. It was subsequently also shown to bind ICAM-2 on vascular endothelial cells, regulating DC migration [27]; both of these interactions occur through N-linked high mannose structures (typically consisting of between five and nine terminal mannose units). Mannose-dependent interactions also account for the ability of DC-SIGN to bind HIV [28] and a plethora of other pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Candida albicans, Helicobacter pylori and Schistosoma mansoni [29••]. DC-SIGN discriminates between ligands not only on the basis of primary mannose groups, but also via secondary binding sites, which accommodate carbohydrates with distinctive geometry conferred by linkage to the primary monosaccharide moiety [30••]. This probably explains the differences in ligand affinity between DC-SIGN and other apparent mannose-specific CLRs such as MR. Further specificity can also be achieved through multimerisation of the receptor at the cell surface [31]; indeed, tetramerisation of DC-SIGN facilitates high-affinity binding to high mannose oligosaccharides, such as those found on HIV [32•].

Despite the obvious ability of DC-SIGN to recognize pathogens, the contribution of this receptor to host defence is unclear. As ligands for DC-SIGN also bind many other CLRs, specific monoclonal antibodies have been used to assess the fate of ligands targeted through individual receptors [33]. Such studies indicate that DC-SIGN targets antigens to late endosomal/lysosomal compartments for degradation and presentation to T cells. Paradoxically, it has been reported that a range of viruses, including HIV [34], hepatitis C virus 35., 36., the recently discovered coronavirus responsible for severe acute respiratory disease [37•], and dengue virus 38., 39. can exploit DC-SIGN to protect virions from the normal pathways of lysosomal degradation and presentation to T cells. In the case of HIV, this interaction allows efficient transinfection of CD4+ T cells in secondary lymphoid organs [34]. More recently, however, Moris and colleagues [40] have challenged this view by showing that, in DCs and DC-SIGN transfected cells, the majority of HIV virions are rapidly degraded in endosomal or lysosomal compartments. Although this pathway normally leads to MHC-II-restricted presentation of epitopes, DC-SIGN-dependent MHC-I-restricted presentation was also evident. It is probable that not all virions are targeted in this way and a small proportion might escape to the cytoplasm or other non-endosomal/non-lysosomal compartments allowing subsequent transinfection of T cells. In addition, as DCs and MØs express many different mannose-specific CLRs, it is likely that virus uptake by these cells proceeds through multiple routes [41].

Data regarding the interaction of M. tuberculosis with DC-SIGN suggest that the pathogen has evolved to exploit the receptor as part of an immunoevasive strategy [42••]. Mannosylated lipoarabinomannan (ManLAM) is a mannose-capped glycolipid found in the cell wall of M. tuberculosis. It appears that ManLAM can induce the secretion of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 from DCs in a DC-SIGN-dependent manner. This interaction also appears to inhibit the expression of co-stimulatory molecules required for efficient stimulation of adaptive immune responses that are normally induced by pathogenic ligands following TLR stimulation.

SIGNR1, one of five murine homologues of the DC-SIGN family of receptors, is essential for the clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae-derived capsular polysaccharides by marginal zone MØs [43]. Although the fate of antigens cleared in this way is not yet known, a study by the same group [44] indicates that dextran is targeted to non-lysosomal compartments in a SIGNR1-transfected MØ cell line. SIGNR1 is also a non-opsonic receptor for yeasts such as Candida albicans [45]. Although it cannot efficiently internalise antigen by itself, it might play an important role in trapping ligands at the cell surface, thereby facilitating recognition and uptake by other PRRs such as dectin-1.

The mannose receptor family

The MR family of multi-lectin receptors includes MR itself as well as Endo-180, DEC-205 and the phospholipase A2 receptor [20]. Of these, only MR and Endo-180 have the capacity to bind carbohydrates in a Ca2+-dependent manner via their CRDs.

MR is the best characterised of these receptors and binds a range of bacteria, yeasts and viruses through interactions between a mannose-type CRD and pathogen-associated high mannose structures. The ability of MR to enhance uptake and processing of mannosylated antigens for presentation by MHC-II [46] has recently been challenged by studies using transfected fibroblasts [47]. MR does, however, appear to have a specialized role in the delivery of pathogen-associated glycolipids, such as lipoarabinomannan, for presentation on CD1b [48].

Although the mannose-type CRD of Endo-180 has a similar ligand spectrum as MR [49], its role as a pathogen clearance receptor has not been investigated. Endo-180 is best known as a fibroblast-expressed receptor for collagen [50], which binds collagen via an amino-terminal fibronectin type II (FN-II) domain, and Endo-180-deficient mice have defects in collagen uptake [51••]. The MR itself also contains a FN-II domain although there are currently no published data regarding its ability to bind collagen. By contrast, the cysteine rich domain of MR endows a capacity to bind endogenous glycoproteins such as sialoadhesin and CD45 bearing sulphated N-acetyl galactosamine or galactose moieties [25], which are expressed by metallophillic MØs in secondary lymphoid organs 52., 53.. These cells are located adjacent to B-cell follicles, and such interactions might influence immune responses to ligands targeted to these cells that might be delivered by a naturally occurring soluble form of the receptor 54., 55.. In addition to these ligands, MR also mediates the clearance of potentially harmful endogenous inflammatory glycoproteins bearing ligands for the mannose-type CRD 56., 57..

The relative importance of MR interactions with such a diverse array of ligands has recently been clarified following the generation of MR-deficient mice by two separate groups 58., 59.. Surprisingly, MR does not appear to be essential for primary immune responses against fungal pathogens, and MR−/− mice are no more susceptible to infection by these pathogens than their wild-type counterparts when mortality and disseminated infection are measured 60.••, 61.••. By contrast, these mice have increased plasma concentrations of endogenous glycoproteins, such as lysosomal hydrolases, confirming an important role for MR in the clearance of self antigens. MR also plays an important role in fertility by controlling levels of the glycosylated pituitary hormone, lutropin. MR+/− mice have decreased litter sizes as a result of abnormalities in the pulsatile release of this hormone [59].

Dectin-1: a pattern-recognition receptor for fungal pathogens

The absence of immune defects in MR−/− mice in response to fungal pathogens highlights the presence of other PRRs responsible for dealing with these microbes. The identification of dectin-1 as a CLR that mediates innate immune responses to β-1,3- and β-1,6-linked glucans present in fungal cell walls [22] is a major advance in our understanding of host responses to such pathogens.

Although many of the other CLRs described in this article participate in the clearance of glycosylated antigens, dectin-1 is unusual as it also plays a central role in eliciting pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α in response to fungal pathogens [62••]. The majority of pro-inflammatory responses to pathogenic ligands are mediated by the TLR family of PRRs and, in the case of dectin-1, collaboration with TLR2 is essential to the response 62.••, 63.••. Dectin-1 contains an immunotyrosine activatory motif (ITAM) within its cytoplasmic tail that is required for interactions with the TLR2 signalling pathway. Independently of TLR2, the ITAM is also required for cytoskeletal rearrangements triggered through dectin-1 preceding phagocytosis [64]. The precise signalling pathways initiated following tyrosine phosphorylation within the ITAM are not well understood. Although it was initially predicted that they might be similar to those seen with other ITAM-bearing receptors, such as the Fc receptors for IgG, a new study suggests that this is not the case and it is likely that dectin-1 responses act through a novel signalling pathway [64].

Interestingly, the intracellular fate of ligands captured through dectin-1 appears to be associated with their size [64]. Receptors such as MR rapidly recycle between the cell surface and lysosomal vesicles where ligands are released and degraded allowing MR to traffic back to the cell surface [20]. Other receptors such as FcγR undergo de novo synthesis and are degraded in lysosomes together with their cargo [65]. Dectin-1, however, has features of both types of trafficking depending on the ligand used. When stimulated with smaller ligands such as laminarin, the receptor recycles to the cell surface but when larger ligands such as glucan phosphate or zymosan are used cell surface dectin-1 expression is reduced [20]. The mechanism of this trafficking is unclear at present but might have significant implications for our understanding of the biological effects of dectin-1 ligands in vivo as well as our understanding of antigen handling by the innate immune system.

As with other CLRs discussed in this review, dectin-1 also interacts with an endogenous ligand present on activated T cells and this can lead to T-cell proliferation when a second stimulus is delivered through CD3 [21]. A more recent study using a short isoform of dectin-1 indicates that it can stimulate both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, inducing co-stimulatory molecule expression and IFN-γ production [66]. Although the nature of this T-cell ligand is unknown, it is known that the interaction occurs through a distinct site from that mediating β-glucan recognition [67].

Conclusions

In recent years our understanding of CLRs has expanded greatly. Beyond their roles as PRRs recognizing pathogens and pathogen-derived ligands, these receptors also interact with a wide range of known and unknown endogenous ligands. Further characterisation of these interactions will be vital to a full understanding of CLR biology. The absence of primary immune defects in MR−/− mice is surprising and it probably reflects an historical attribution of mannose inhibitable phenomena in the literature to MR before the discovery of other APC-expressed mannose-type CLRs.

The generation of knockout models for these other CLRs should allow us to clarify the individual functions of these receptors in immune and non-immune phenomena. The coming years should further expand our knowledge of the roles played by CLRs in the immune system. Two major issues will be: the identification and characterisation of endogenous ligands observed for CLRs such as dectin-1 and dectin-2; and, understanding the full signalling capacity of CLRs and their interaction with other antigen sensing receptors.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by grants from the Medical Research Council and The Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research.

References

- 1.Taylor P, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin H, Brown G, Gordon S: Macrophage Receptors and Immune Regulation. Annu Rev Immunol 2005, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Garcia-Garcia E., Rosales C. Signal transduction during Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:1092–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehlers M.R. CR3: a general purpose adhesion-recognition receptor essential for innate immunity. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart S.P., Smith J.R., Dransfield I. Phagocytosis of opsonized apoptotic cells: roles for ‘old-fashioned’ receptors for antibody and complement. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2003.02330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janeway C.A., Jr. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54:1–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barclay A.N., Wright G.J., Brooke G., Brown M.H. CD200 and membrane protein interactions in the control of myeloid cells. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown E.J., Frazier W.A. Integrin-associated protein (CD47) and its ligands. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01906-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleharski J.R., Kiessler V., Buonsanti C., Sieling P.A., Stenger S., Colonna M., Modlin R.L. A role for triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in host defense during the early-induced and adaptive phases of the immune response. J Immunol. 2003;170:3812–3818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.•.Dunzendorfer S., Lee H.K., Soldau K., Tobias P.S. TLR4 is the signaling but not the lipopolysaccharide uptake receptor. J Immunol. 2004;173:1166–1170. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A study demonstrating that, although TLR4 mediates responses to LPS, it does not play a role in the clearance of this ligand.

- 11.•.Geijtenbeek T.B., van Vliet S.J., Engering A., t Hart B.A., van Kooyk Y. Self- and nonself-recognition by C-type lectins on dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:33–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A recent paper highlighting important functions for members of the Ig superfamily in regulating myeloid cell function.

- 12.Peiser L., Mukhopadhyay S., Gordon S. Scavenger receptors in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cambi A., Figdor C.G. Dual function of C-type lectin-like receptors in the immune system. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhopadhyay S., Herre J., Brown G.D., Gordon S. The potential for Toll-like receptors to collaborate with other innate immune receptors. Immunology. 2004;112:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geijtenbeek T.B., Torensma R., van Vliet S.J., van Duijnhoven G.C., Adema G.J., van Kooyk Y., Figdor C.G. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park C.G., Takahara K., Umemoto E., Yashima Y., Matsubara K., Matsuda Y., Clausen B.E., Inaba K., Steinman R.M. Five mouse homologues of the human dendritic cell C-type lectin, DC-SIGN. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1283–1290. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.10.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ariizumi K., Shen G.L., Shikano S., Ritter R., III, Zukas P., Edelbaum D., Morita A., Takashima A. Cloning of a second dendritic cell-associated C-type lectin (dectin-2) and its alternatively spliced isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11957–11963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valladeau J., Ravel O., Dezutter-Dambuyant C., Moore K., Kleijmeer M., Liu Y., Duvert-Frances V., Vincent C., Schmitt D., Davoust J. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dzionek A., Sohma Y., Nagafune J., Cella M., Colonna M., Facchetti F., Gunther G., Johnston I., Lanzavecchia A., Nagasaka T. BDCA-2, a novel plasmacytoid dendritic cell-specific type II C-type lectin, mediates antigen capture and is a potent inhibitor of interferon alpha/beta induction. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1823–1834. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.East L., Isacke C.M. The mannose receptor family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:364–386. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ariizumi K., Shen G.L., Shikano S., Xu S., Ritter R., III, Kumamoto T., Edelbaum D., Morita A., Bergstresser P.R., Takashima A. Identification of a novel, dendritic cell-associated molecule, dectin-1, by subtractive cDNA cloning. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20157–20167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909512199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown G.D., Gordon S. Immune recognition. A new receptor for beta-glucans. Nature. 2001;413:36–37. doi: 10.1038/35092620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McQueen K.L., Parham P. Variable receptors controlling activation and inhibition of NK cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:615–621. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drickamer K. Engineering galactose-binding activity into a C-type mannose-binding protein. Nature. 1992;360:183–186. doi: 10.1038/360183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiete D.J., Beranek M.C., Baenziger J.U. A cysteine-rich domain of the “mannose” receptor mediates GalNAc-4-SO4 binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2089–2093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.•.Adachi Y., Ishii T., Ikeda Y., Hoshino A., Tamura H., Aketagawa J., Tanaka S., Ohno N. Characterization of beta-glucan recognition site on C-type lectin, dectin 1. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4159–4171. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4159-4171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper describes the mutational analysis of the CRD of dectin-1 and identifies the residues involved in the Ca2+-independent recognition of β-glucans.

- 27.Geijtenbeek T.B., Krooshoop D.J., Bleijs D.A., van Vliet S.J., van Duijnhoven G.C., Grabovsky V., Alon R., Figdor C.G., van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN-ICAM-2 interaction mediates dendritic cell trafficking. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:353–357. doi: 10.1038/79815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtis B.M., Scharnowske S., Watson A.J. Sequence and expression of a membrane-associated C-type lectin that exhibits CD4-independent binding of human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8356–8360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.••.Appelmelk B.J., van Die I., van Vliet S.J., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C.M., Geijtenbeek T.B., van Kooyk Y. Cutting edge: carbohydrate profiling identifies new pathogens that interact with dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin on dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:1635–1639. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A novel approach to determining the ligand profile of DC-SIGN using a carbohydrate ‘array’.

- 30.••.Guo Y., Feinberg H., Conroy E., Mitchell D.A., Alvarez R., Blixt O., Taylor M.E., Weis W.I., Drickamer K. Structural basis for distinct ligand-binding and targeting properties of the receptors DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:591–598. doi: 10.1038/nsmb784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Differences in the ligand preference between these two closely related receptors can be attributed to the conformation of secondary linkages between saccharide units in complex oligosaccharide ligands.

- 31.Mitchell D.A., Fadden A.J., Drickamer K. A novel mechanism of carbohydrate recognition by the C-type lectins DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Subunit organization and binding to multivalent ligands. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28939–28945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.•.Bernhard O.K., Lai J., Wilkinson J., Sheil M.M., Cunningham A.L. Proteomic analysis of DC-SIGN on dendritic cells detects tetramers required for ligand binding but no association with CD4. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A study confirming the importance of tertiary organization of DC-SIGN at the cell surface for high affinity ligand binding. This could well be true for other CLRs.

- 33.Engering A., Geijtenbeek T.B., van Vliet S.J., Wijers M., van Liempt E., Demaurex N., Lanzavecchia A., Fransen J., Figdor C.G., Piguet V. The dendritic cell-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:2118–2126. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geijtenbeek T.B., Kwon D.S., Torensma R., van Vliet S.J., van Duijnhoven G.C., Middel J., Cornelissen I.L., Nottet H.S., KewalRamani V.N., Littman D.R. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cormier E.G., Durso R.J., Tsamis F., Boussemart L., Manix C., Olson W.C., Gardner J.P., Dragic T. L-SIGN (CD209L) and DC-SIGN (CD209) mediate transinfection of liver cells by hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14067–14072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405695101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwig I.S., Lekkerkerker A.N., Depla E., Bosman F., Musters R.J., Depraetere S., van Kooyk Y., Geijtenbeek T.B. Hepatitis C virus targets DC-SIGN and L-SIGN to escape lysosomal degradation. J Virol. 2004;78:8322–8332. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8322-8332.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.•.Yang Z.Y., Huang Y., Ganesh L., Leung K., Kong W.P., Schwartz O., Subbarao K., Nabel G.J. pH-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is mediated by the spike glycoprotein and enhanced by dendritic cell transfer through DC-SIGN. J Virol. 2004;78:5642–5650. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5642-5650.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Further confirmation that viruses can exploit DC-SIGN to avoid degradation and promote infectivity.

- 38.Tassaneetrithep B., Burgess T.H., Granelli-Piperno A., Trumpfheller C., Finke J., Sun W., Eller M.A., Pattanapanyasat K., Sarasombath S., Birx D.L. DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:823–829. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navarro-Sanchez E., Altmeyer R., Amara A., Schwartz O., Fieschi F., Virelizier J.L., Arenzana-Seisdedos F., Despres P. Dendritic-cell-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin is essential for the productive infection of human dendritic cells by mosquito-cell-derived dengue viruses. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:723–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moris A., Nobile C., Buseyne F., Porrot F., Abastado J.P., Schwartz O. DC-SIGN promotes exogenous MHC-I-restricted HIV-1 antigen presentation. Blood. 2004;103:2648–2654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turville S.G., Cameron P.U., Handley A., Lin G., Pohlmann S., Doms R.W., Cunningham A.L. Diversity of receptors binding HIV on dendritic cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:975–983. doi: 10.1038/ni841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.••.Geijtenbeek T.B., Van Vliet S.J., Koppel E.A., Sanchez-Hernandez M., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C.M., Appelmelk B., Van Kooyk Y. Mycobacteria target DC-SIGN to suppress dendritic cell function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:7–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Data demonstrating that M. tuberculosis exploits DC-SIGN to mediate immunosuppression by inducing IL-10 production.

- 43.Kang Y.S., Kim J.Y., Bruening S.A., Pack M., Charalambous A., Pritsker A., Moran T.M., Loeffler J.M., Steinman R.M., Park C.G. The C-type lectin SIGN-R1 mediates uptake of the capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the marginal zone of mouse spleen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:215–220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307124101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang Y.S., Yamazaki S., Iyoda T., Pack M., Bruening S.A., Kim J.Y., Takahara K., Inaba K., Steinman R.M., Park C.G. SIGN-R1, a novel C-type lectin expressed by marginal zone macrophages in spleen, mediates uptake of the polysaccharide dextran. Int Immunol. 2003;15:177–186. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor P.R., Brown G.D., Herre J., Williams D.L., Willment J.A., Gordon S. The role of SIGNR1 and the beta-glucan receptor (dectin-1) in the nonopsonic recognition of yeast by specific macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;172:1157–1162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan M.C., Mommaas A.M., Drijfhout J.W., Jordens R., Onderwater J.J., Verwoerd D., Mulder A.A., van der Heiden A.N., Ottenhoff T.H., Cella M. Mannose receptor mediated uptake of antigens strongly enhances HLA-class II restricted antigen presentation by cultured dendritic cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;417:171–174. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-9966-8_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Napper C.E., Taylor M.E. The mannose receptor fails to enhance processing and presentation of a glycoprotein antigen in transfected fibroblasts. Glycobiology. 2004;14:7C–12C. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prigozy T.I., Sieling P.A., Clemens D., Stewart P.L., Behar S.M., Porcelli S.A., Brenner M.B., Modlin R.L., Kronenberg M. The mannose receptor delivers lipoglycan antigens to endosomes for presentation to T cells by CD1b molecules. Immunity. 1997;6:187–197. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.East L., Rushton S., Taylor M.E., Isacke C.M. Characterization of sugar binding by the mannose receptor family member, Endo180. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50469–50475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wienke D., MacFadyen J.R., Isacke C.M. Identification and characterization of the endocytic transmembrane glycoprotein Endo180 as a novel collagen receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3592–3604. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.••.East L., McCarthy A., Wienke D., Sturge J., Ashworth A., Isacke C.M. A targeted deletion in the endocytic receptor gene Endo180 results in a defect in collagen uptake. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:710–716. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Endo-180 plays an important non-redundant role in the clearance of collagen through its FN-II domain.

- 52.Martinez-Pomares L., Kosco-Vilbois M., Darley E., Tree P., Herren S., Bonnefoy J.Y., Gordon S. Fc chimeric protein containing the cysteine-rich domain of the murine mannose receptor binds to macrophages from splenic marginal zone and lymph node subcapsular sinus and to germinal centers. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1927–1937. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez-Pomares L., Crocker P.R., Da Silva R., Holmes N., Colominas C., Rudd P., Dwek R., Gordon S. Cell-specific glycoforms of sialoadhesin and CD45 are counter-receptors for the cysteine-rich domain of the mannose receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35211–35218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez-Pomares L., Reid D.M., Brown G.D., Taylor P.R., Stillion R.J., Linehan S.A., Zamze S., Gordon S., Wong S.Y. Analysis of mannose receptor regulation by IL-4, IL-10, and proteolytic processing using novel monoclonal antibodies. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:604–613. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor P.R., Zamze S., Stillion R.J., Wong S.Y., Gordon S., Martinez-Pomares L. Development of a specific system for targeting protein to metallophilic macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1963–1968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308490100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imai K., Yoshimura T. Endocytosis of lysosomal acid phosphatase; involvement of mannose receptor and effect of lectins. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;33:1201–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shepherd V.L., Hoidal J.R. Clearance of neutrophil-derived myeloperoxidase by the macrophage mannose receptor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1990;2:335–340. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/2.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee S.J., Evers S., Roeder D., Parlow A.F., Risteli J., Risteli L., Lee Y.C., Feizi T., Langen H., Nussenzweig M.C. Mannose receptor-mediated regulation of serum glycoprotein homeostasis. Science. 2002;295:1898–1901. doi: 10.1126/science.1069540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mi Y., Shapiro S.D., Baenziger J.U. Regulation of lutropin circulatory half-life by the mannose/N-acetylgalactosamine-4-SO4 receptor is critical for implantation in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:269–276. doi: 10.1172/JCI13997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.••.Lee S.J., Zheng N.Y., Clavijo M., Nussenzweig M.C. Normal host defense during systemic candidiasis in mannose receptor-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:437–445. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.437-445.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; One of two papers 60.••, 61.•• that indicate that MR is not required for effective primary immune responses against fungal pathogens despite an important role for this receptor in clearing such microbes in vitro.

- 61.••.Swain S.D., Lee S.J., Nussenzweig M.C., Harmsen A.G. Absence of the macrophage mannose receptor in mice does not increase susceptibility to Pneumocystis carinii infection in vivo. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6213–6221. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6213-6221.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See annotation to [60••].

- 62.••.Brown G.D., Herre J., Williams D.L., Willment J.A., Marshall A.S., Gordon S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1119–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; One of two papers 62.••, 63.•• demonstrating a collaboration between dectin-1 and TLR2 for pro-inflammatory responses to fungal pathogens.

- 63.••.Gantner B.N., Simmons R.M., Canavera S.J., Akira S., Underhill D.M. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll-like receptor 2. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1107–1117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See annotation to [62••].

- 64.Herre J., Marshall A.S., Caron E., Edwards A.D., Williams D.L., Schweighoffer E., Tybulewicz V., Reis E.S.C., Gordon S., Brown G.D. Dectin-1 utilizes novel mechanisms for yeast phagocytosis in macrophages. Blood. 2004 doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Worth R.G., Mayo-Bond L., Kim M.K., van de Winkel J.G., Todd R.F., III, Petty H.R., Schreiber A.D. The cytoplasmic domain of FcgammaRIIA (CD32) participates in phagolysosome formation. Blood. 2001;98:3429–3434. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grunebach F., Weck M.M., Reichert J., Brossart P. Molecular and functional characterization of human Dectin-1. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00928-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Willment J.A., Gordon S., Brown G.D. Characterization of the human beta -glucan receptor and its alternatively spliced isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43818–43823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DeFife K.M., Jenney C.R., McNally A.K., Colton E., Anderson J.M. Interleukin-13 induces human monocyte/macrophage fusion and macrophage mannose receptor expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:3385–3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Doyle A.G., Herbein G., Montaner L.J., Minty A.J., Caput D., Ferrara P., Gordon S. Interleukin-13 alters the activation state of murine macrophages in vitro: comparison with interleukin-4 and interferon-gamma. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1441–1445. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soilleux E.J., Morris L.S., Leslie G., Chehimi J., Luo Q., Levroney E., Trowsdale J., Montaner L.J., Doms R.W., Weissman D. Constitutive and induced expression of DC-SIGN on dendritic cell and macrophage subpopulations in situ and in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:445–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahara K., Omatsu Y., Yashima Y., Maeda Y., Tanaka S., Iyoda T., Clausen B.E., Matsubara K., Letterio J., Steinman R.M. Identification and expression of mouse Langerin (CD207) in dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14:433–444. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guironnet G., Dezutter-Dambuyant C., Vincent C., Bechetoille N., Schmitt D., Peguet-Navarro J. Antagonistic effects of IL-4 and TGF-beta1 on Langerhans cell-related antigen expression by human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:845–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Willment J.A., Lin H.H., Reid D.M., Taylor P.R., Williams D.L., Wong S.Y., Gordon S., Brown G.D. Dectin-1 expression and function are enhanced on alternatively activated and GM-CSF-treated macrophages and are negatively regulated by IL-10, dexamethasone, and lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2003;171:4569–4573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]